A singular figure indeed! A medium-sized, well-built man, straight, erect, and in well-fitting uniform, an elegant riding-whip in hand, his appearance was distinguished and striking. But the head, the hair were extraordinary. Long ringlets flowed loosely over his shoulders, trimmed and highly perfumed; his beard likewise was curling and giving out the scents of Araby. 2

George Pickett was born of a good Richmond pedigree in 1825, making him 38 years old at Gettysburg. His uncle had helped him get an appointment to West Point in 1842 where he graduated last in his class of 1846. 3 While West Point grades were seldom a predictor of battlefield success, it is worth noting that Moxley Sorrel also later recalled that Longstreet always “made us give him [Pickett] things very fully; indeed, sometimes stay with him to make sure he did not get astray.” 4

Most Civil War officers’ resumes were filled with years of mundane prewar garrison duty on the frontier, and Pickett was no exception. But he also had several notable encounters that gained national attention. During the Mexican-American War, Second Lieutenant Pickett showed great bravery (and received a brevet promotion to captain) during the battle of Chapultepec, when he took the colors from wounded Lt. James Longstreet and carried them over the fortress parapet. 5 In 1859, Pickett led a small infantry garrison on San Juan Island (today part of Washington State) that successfully participated in a standoff against 1,000 British forces and three warships in a boundary dispute over the shooting of a pig. (The event appropriately became known as the Pig War.) Pickett famously exclaimed during the episode, “We’ll make a Bunker Hill of it!” but diplomacy eventually prevailed.

Pickett also married twice during this period. An 1851 marriage ended when his wife died in childbirth later that year. A second marriage to an Indian woman also ended when she died in childbirth in 1856 or 1857. When Pickett returned east, he left his surviving half-Indian son James with a friend and the boy was later put in care of a white farmer couple. Pickett never returned for his child, although he reportedly left financial support and third wife LaSalle Corbell Pickett later corresponded extensively with the son. James Pickett became an artist, never married, and died in 1889.6

George Pickett resigned from the U.S. Army in support of his native Virginia and the Confederacy when the Civil War broke out. Colonel Pickett made brigadier general in February 1862 and led his new brigade capably in action at Williamsburg and Seven Pines before being shot in the shoulder at Gaines’s Mill. Pickett was away from the army for three months to recover.7

When he returned in late September 1862, Pickett was quickly promoted to major general in command of a division in Longstreet’s newly created First Corps. Some have speculated Pickett’s promotion was due to the influence of his friend Longstreet. Their personal relationship certainly did not hurt Pickett’s cause, but he also had seniority and a good record as a brigadier. General Lee endorsed the promotion, which would be Pickett’s last within the Army of Northern Virginia.8 Unfortunately, Pickett’s Division saw no real combat at Fredericksburg and was detached with Longstreet foraging during the Chancellorsville campaign.

Moxley Sorrel recalled Pickett as being “very friendly, was a good fellow, a good brigadier. He had been in Longstreet’s old Army regiment, and the latter was exceedingly fond of him.”9 But if Pickett enjoyed the friendship of General Longstreet, the same cannot be said for his relationship with Robert E. Lee. Although there is some debate amongst historians over the level of Lee and Pickett’s frigid feelings for each other, the record seems to provide ample suggestions that their relations were less than cordial.

They were complete contrasts in style: the duty-bound and frosty Lee vs. the self-indulgent and emotional Pickett. Whatever the extent of their personal issues, the problems appear to predate Gettysburg. In January 1863, Lee criticized the condition and discipline of Pickett’s men to Longstreet. In February, Pickett’s men were detached to guard Richmond and stayed away throughout Longstreet’s spring Suffolk campaign. Some have suggested that detaching officers was a favorite tactic of Lee’s to rid himself of problems. Pickett sent several testy dispatches that spring, complaining about travel restrictions and also about the apparent refusal of Lee’s headquarters to answer his inquiries. 10 On the march into Pennsylvania, female admirers asked for a lock of Lee’s hair. Lee declined but suggested that Pickett “would be pleased to give them one of his curls.” The sensitive Pickett was reportedly not amused to be the butt of Marse Robert’s joke. 11

Several accounts suggest that by the end of the war the Lee-Pickett relationship had completely broken down. War Department clerk John Jones wrote in 1864 that it was “possible” Pickett “may have…criticized Lee.” 12 Eppa Hunton was the colonel of the 8th Virginia at Gettysburg. He observed in 1904: “Pickett had lost caste entirely with General Lee. I cannot tell exactly what the trouble was. It is reported that he abused and criticized Lee on the [Appomattox] retreat for not surrendering, and condemned him severely for continuing the war. I cannot say that this is true, or whether General Lee was visiting discipline upon Pickett for his loss of Five Forks and Sailor’s Creek…” 13 Confederate cavalier John Mosby likewise wrote of bad blood between the two Virginians.

Part of Lee’s issues may have been Pickett’s well-known romantic escapades. Prior to the Gettysburg Campaign, the widower fell in love with Virginia teenager LaSalle “Sallie” Corbell, who may have met Pickett when she was as young as four. 14 Sorrel recalled that Pickett fell “in love with all the ardor of youth” and he would sometimes leave his command to spend nights with Sallie. On one occasion, Pickett asked Sorrel for permission to leave because Longstreet was “tired of [dealing with] it.” Sorrel refused “but Pickett went all the same, nothing could hold him back from that pursuit…I don’t think his division benefited by such carpet-knight doings in the field.” 15

Pickett and Sallie were married in November 1863. (Lee did not attend the ceremony and instead sent a fruitcake as a gift.) Eppa Hunton recalled, “Pickett was a gallant man. Up to the time he was married, I had the utmost confidence in his gallantry, but I believe that no man who married during the war was as good a soldier after, as before marriage….marriage during the war seemed to demoralize them.” 16

Much of Pickett’s reputation as a swashbuckling scion of the Old South, and a supposed favorite of Lee’s, comes to us from LaSalle’s writing and speaking engagements conducted decades after his death. Unfortunately, many of her yarns are generally considered historically unreliable such as the popular story that Pickett’s West Point appointment was secured by Abraham Lincoln. Her tall tale that Lincoln then paid a visit to the Pickett household in Richmond during the closing days of the war is equally dubious. 17 Likewise, modern research has even cast some doubts on her touching story that Pickett handled the funeral arrangements for Longstreet’s children who died of disease during the winter of 1862.18

Lee may not have appreciated Pickett’s emotionally crying out, “I have no division!” following the repulse of July 3. However, other officers (such as Cadmus Wilcox) were also reported to be in a similar condition following the debacle. 19 Pickett probably did not help his cause when he questioned Lee on July 8 about being assigned to guard Union prisoners on the retreat from Gettysburg. 20 Pickett’s mortification at being assigned guard duty was shared by his men. Charles Loehr said the order “was but little relished by the men, most of them considering it as almost a disgrace to act as provost guard; however, orders must be obeyed.” 21

Much has also been made of Pickett’s missing official report of the battle, although his was not the only one omitted from publication. It reportedly complained about a lack of support (which was not uncommon in Civil War battle reports), but Lee asked for it to be resubmitted, cautioning, “we have the enemy to fight, and must carefully, at this critical moment, guard against dissensions which the reflections in your report would create. I will, therefore, suggest that you destroy both copy and original, substituting one confined to casualties merely.” 22 Who exactly Pickett blamed is debatable, but perhaps Lee considered the contrast between Pickett’s apparent willingness to criticize others while Lee had openly accepted the blame himself.

Pickett’s post-Gettysburg career is perhaps best remembered for his disastrous defeat at Five Forks in April 1865 which occurred while he was several miles in the rear enjoying a shad bake. Pickett was reportedly relieved of command several days later following another rout at Sailor’s Creek. Lee allegedly passed Pickett and coldly scoffed, “I thought that man was no longer with the army.” Yet there is historical controversy around even this. Walter Taylor, Lee’s chief of staff, wrote after the war that he issued orders for Lee relieving Pickett, but no copies of this order survive. As late as April 11, 1865, Pickett was still signing documents as “Maj. Genl. Comdg.” It has been speculated that in the chaos of the Army of Northern Virginia’s final days, the relief order never reached Pickett. Taylor later explained that although Pickett was relieved of his division command, he was not dismissed from the army, and thus explains why he was still present at Appomattox. 23

LaSalle’s always questionable recollections are the source of a frequently quoted postwar anecdote concerning “Pickett’s Charge.” Mrs. Pickett claimed that while attending a dinner in Canada, General Pickett was asked by dignitaries as to who was responsible for the Gettysburg defeat. “With a twinkle in his eye,” George Pickett replied, “I think the Yankees had a little something to do with it.” 24

Yet another often-repeated conclusion to the Lee-Pickett saga occurred in March 1870. (Although like so many aspects of Pickett’s legend, this too is debated by scholars.) Confederate cavalryman John Mosby arranged a meeting in Richmond between Pickett and a dying Lee. Mosby alleged that the meeting was “cold and formal, and evidently embarrassing to both commanders.” Mosby and Pickett departed after only a few minutes. Pickett reportedly spoke very bitterly of Lee, calling him “that old man” and exclaiming that Lee “had my division massacred at Gettysburg.” Mosby replied, “Well, it made you immortal.” 25

George Pickett died July 30, 1875. He is buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery near about 2,000 of Gettysburg’s Confederate dead, many presumably being from his own division, who had been reinterred there in 1872.

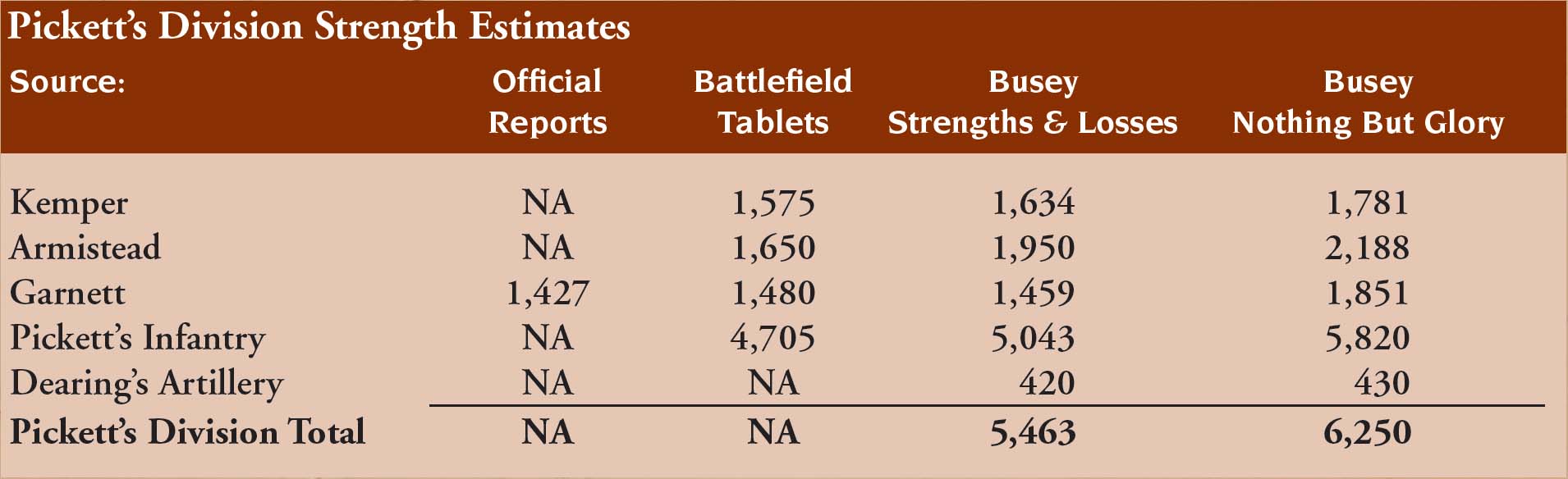

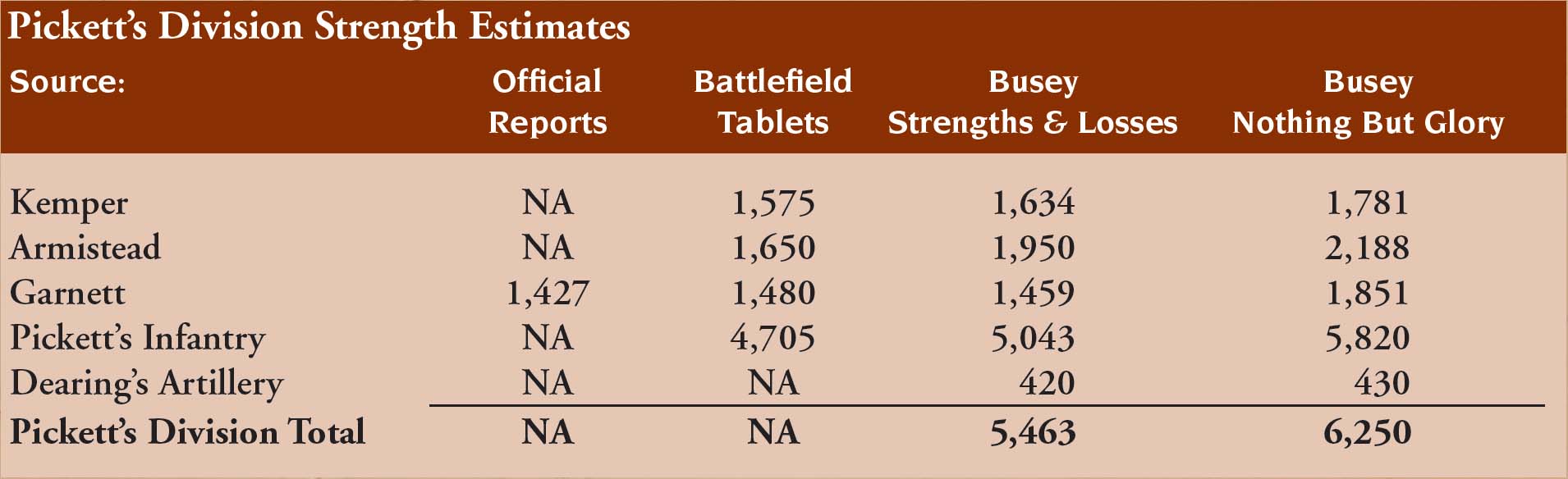

How many infantrymen were in Pickett’s Division and how many actually participated in the charge? As with assessments of Pettigrew and Trimble’s strength, the answer is uncertain. In addition to the reporting challenges noted previously, the problem also exists because some Confederate muster rolls are missing and all reconstructions require a degree of mathematical guesswork to arrive at their totals. Even Lee’s officers could not agree on the aggregates within the army. 1

One source of confusion arises from the habit of some researchers to include artillery strength when assessing Pickett’s overall manpower. Our question attempts to identify the number of infantrymen who stepped off from Seminary Ridge and literally made the charge. Our desire to exclude artillerymen from the total is in no way dismissive of their service, but their inclusion simply does not represent those whom we traditionally consider as having actually marched across the mile of open ground to Cemetery Ridge.

Another source of confusion exists, as researcher John Busey noted, because Confederate officers often interchangeably reported strengths as “effectives,” “men,” and “rifles” to generally represent the enlisted men. 2 This observation was certainly true in Pickett’s Division. General Pickett himself wrote on June 21: “I have now only three brigades, not more than 4,795 men.” 3 Pickett’s staff officer Walter Harrison wrote that there were only 4,481 “muskets” and an “aggregate effective strength” of 4,700 “rank and file.” 4 Arthur Fremantle described the division as a “weak one (under 5,000), owing to the absence of two brigades.” 5 Longstreet thought in Annals of the War, “the real strength of Pickett’s Division was 4,500 bayonets.” 6 Captain Robert Bright on Pickett’s staff believed: “forty-seven hundred muskets, with officers added, five thousand strong.”7 David Johnston, 7th Virginia, wrote in his postwar reminiscences of “about 4,700 men, which included the General’s staff, and regimental officers.” 8 It has been proposed that the Confederates, primarily using Walter Harrison as their source, intentionally under-estimated their strength in order to inflate their post-battle valor. This rationale does not explain, however, examples such as General Pickett’s June 21 estimate.

The three brigade monuments on the battlefield for Garnett, Kemper, and Armistead add up to 4,705 men present. (Armistead’s Brigade monument adds to 1,650, Garnett’s to 1,480, and Kemper’s to 1,575.) Garnett’s Brigade was the only one of Pickett’s brigades to estimate their combat strength via an official report. Major Charles Peyton of the 19th Virginia filed for the deceased General Garnett and stated that their command went into action with 1,427 men. 9 This is actually even lower than Garnett’s tablet total of 1,480 men. If we assume, as a mere statistical exercise and nothing else, that the other two brigade tablets are also approximately 4% higher than what would have been reported, then we would expect 4,516 men to have been reported for the entire division. In Garnett’s case at least, a radically higher total then must assume that both Major Peyton and the source for the battlefield monuments were drastically wrong.

The field returns for Lee’s army suggest potentially higher numbers for the division. The July 20 field returns count 3,733 officers and men present for duty. 10 If we add the 2,863 casualties noted in General Longstreet’s report then we achieve an estimated total of about 6,596 men in action at Gettysburg (the sum of July 20 rolls + reported casualties.) 11 But as Busey noted, reliance on the returns yield their own problems and the methodology used above would undoubtedly double-count some unknown number of wounded who were included in Longstreet’s initial casualty total but had returned to duty by July 20. 12

Amongst modern historical studies, George Stewart’s once-considered-definitive Pickett’s Charge (1959) accepted approximately 4,700 in the ranks. 13 But more recent studies routinely bias toward higher totals.

The influential John Busey and David Martin, in their Regimental Strengths and Losses (2005, 4th Edition), estimated 5,944 men present and 5,474 engaged under Pickett at Gettysburg. However, in detail, the engaged strength represents only 4,528 enlisted infantrymen. The remainder were comprised of 526 officers and 420 artillerymen. If we subtract the artillerymen, then this again would imply roughly 5,054 officers and infantrymen engaged in the charge. 14 Gettysburg National Military Park historian Kathy Georg Harrison estimated “some 5,800 infantrymen strong, including [emphasis added] those on detail as teamsters, drovers, cooks, aids, and ambulance drivers.” The addition of artillery brought Pickett’s total to “over 6,200 men.” 15 As part of Harrison’s work, researcher John Busey then revised his totals to 5,830 infantry, 430 artillerymen, and 6,260 total engaged under Pickett.16 Numerous historical studies have since accepted roughly 5,830 “men on the battle line” as the engaged July 3 infantry strength although Harrison initially included those on support detail in this total. 17

Measurements on the field are another factor to consider. The distance from Garnett’s approximate left, past the Spangler farm, and stretching toward the Sherfy farm to equate Kemper’s right flank is between 1,100 to 1,300 yards. Using a 1,100 yard combined front would allow for 3,300 men in two ranks. Armistead’s starting position from the Spangler farm lane to the corner of Spangler’s woodlot is about 500 yards, or about room for 1,500 men. Such distances would suggest about 4,800 men in the ranks when combining the three brigades. Adding at least another 300 men in skirmish lines (a 1,100 yard front would permit about 275 skirmishers at 5 pace intervals) would bring the total to about 5,100. 18

Unfortunately, the honest answer is that no one will ever know exactly how many of Pickett’s men participated in the charge. Whether the starting total was 5,830 or closer to the original suggestions of only 5,000 infantrymen, we must then also deduct several hundred from this total due to various detachments for support roles, stragglers, and casualties from the cannonade and oppressive heat. David Johnston of the 7th Virginia felt confident that “not less than 300 of Pickett’s men were killed or injured by artillery fire.” 19 When all factors are considered, the number of infantrymen who physically stepped off from Seminary Ridge with Pickett that afternoon was probably under 5,000 men.

It is also worth remembering that two of Pickett’s brigades, commanded by Micah Jenkins and Montgomery Corse, were detached from the division and deprived Lee of approximately 3,700 additional men at Gettysburg. 20 Pickett complained to Lee’s headquarters on June 21:

I have the honor to report that in point of numerical strength this division has been very much weakened…I have now only three brigades, not more than 4,795 men, and unless these absent troops are certainly to rejoin me, I beg that another brigade be sent to this division ere we commence the campaign. I ask this in no spirit of complaint, but merely as an act of justice to my division and myself, for it is well known that a small division will be expected to do the same amount of hard service as a large one, and, as the army is now divided, my division will be, I think, decidedly the weakest. 21

Pickett was wasting his energy in complaining to Lee, given that Lee had been futilely trying to get President Davis and the Richmond authorities to return all detached troops, including Pickett’s, to the army. On June 29, Walter Taylor advised Pickett on Lee’s behalf: “I am directed by the commanding general to say that he has repeatedly requested that the two brigades be returned, and had hoped that at least one of them (Corse’s) would have been sent to the division ere this. There is no other brigade in the army which could be assigned to the division at this time.” 22 We know that even at reduced strength, Pickett’s men did at least briefly penetrate the Union defenses. Gettysburg students are left to ponder: Would the addition of 3,700 presumably fresh men have had any material impact on the outcome of July 3? Like most historical ”what ifs,” we will never know, but their absence certainly did not help their cause.

From the Virginia Monument, we will continue to drive south on West Confederate Avenue for roughly another 0.5 miles.

You will pass a War Department tablet on your right to Brig. General Edward Perry’s Florida Brigade. General Perry was absent at Gettysburg due to illness and his brigade was commanded by Col. David Lang. Farther on is the Florida State Memorial and shortly afterwards you will see another War Department tablet dedicated to the Alabama brigade commanded by Brig. General Cadmus Wilcox. As both Wilcox and Lang’s brigades will be discussed at this stop, you may choose to park your vehicle at either monument.

Note, however, these monuments were placed here to conform with the heavily trafficked West Confederate Avenue and do not represent the positions that Wilcox and Lang’s men actually occupied prior to the assault. To obtain their actual perspectives, you may choose to walk about 620 yards east from here toward the Emmitsburg Road. The Henry Spangler farm buildings will be on your left as you walk. If the ground conditions are not conducive to walking in the fields themselves, as an alternate route you may elect to walk along the Spangler farm lane itself before veering into the fields south of the Spangler property. Note that while the Spangler farm is National Park Service property, it is also used as a private residence. Please do not approach the house and respect the privacy of the residents.

STOP 5 Support of Wilcox & Lang’s Brigades (Wilcox Brigade Tablet and Florida State Memorial)

GPS: 39°48’32.62”N, 77°15’17.41”W; Elev. 537 ft.

One of the greatest tactical challenges facing General Longstreet was the protection of his flanks as his attacking force advanced over nearly one mile of open ground. General Kemper’s Brigade on the right of Pickett’s Division line was forced to significantly expose their right flank to Union fire after crossing the Emmitsburg Road at distances beginning at roughly 1,000 yards but soon diminished to as little as 300-400 yards as they veered north toward the salient target.