Chapter 8

Though Bill had hobnobbed with politicians, he generally stayed away from politics and was very wary about his father becoming too involved with a single candidate during the heated 1960 presidential election between Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy. Republican friend Cliff Folger asked J.W. to be one of an elite group of twenty “VIPs” who would contribute up to $30,000 for Nixon’s campaign. “Cliff promised to make me an Ambassador or something, but I am not interested,” J.W. wrote. Instead, he supported Nixon because he found him to be “a brilliant man, full of sound ideas.”1

As the campaign heated up in the fall, he agreed to chair “Restaurant Voters for Nixon.” He viewed the Democratic candidate, Senator Kennedy, as “a smart fellow but immature and dishonest.” J.W. felt that even though he was taking “a calculated risk” siding with Nixon, “there is no alternative.” Bill urged his father, for the good of the company, not to become too enmeshed in the Nixon campaign.

With a Kennedy win, it was the second political mistake that year that Bill had advised his father against. The first was J.W.’s attempt to personally lobby outgoing President Eisenhower for a federal contract—an effort that blew up in his face.

In April 1960, J.W. went to the White House to talk to Eisenhower about plans to build Dulles Airport outside D.C. J.W. was anxious to get a federal contract for food service at the airport. Used to mixing friendship with business, and accustomed to an easy relationship with the president, J.W. likely had no idea he was crossing a line. Ike was “very friendly” when J.W. asked for help during the face-to-face visit, but the next day a White House secretary called with a curt message. “The President had talked with Gen. Pete Quesada and he would see me. The rest is up to me.” As the head of the new Federal Aviation Administration, Quesada had sole control over who got Dulles contracts.

J.W. met with Quesada five days after the Oval Office visit, but it was “a waste of time.” Hot Shoppes would not get the contract. Quesada didn’t say so, but Eisenhower could not risk the appearance of favoritism for a friend. “My father did a lot of amazing things, but this was one of the dumbest—and I thought it would be,” Bill recalled. He understood what J.W. didn’t, that the president couldn’t help him, and Ike would likely have to sell all his Hot Shoppes stock as a result of the request. Thus, in one short, ill-advised visit, J.W. cost the company a key contract and its most prominent stockholder.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, Milt Barlow had launched an unrelenting campaign of his own to become the president of Hot Shoppes. In mid-October, J.W. received a letter from Barlow almost demanding that he be allowed to replace J.W. as president, become a member of the board, and get 50,000 shares of stock and a strong deferred compensation package. “Most colossal nerve I have ever experienced,” J.W. wrote.2

J.W. arranged the board position for Barlow, but when J.W. and Allie went on a round-the-world trip in early 1961, he left written instructions that if anything happened to him, Bill would take over as president. After J.W. returned safely, he asked Bill what he would do if Barlow were his problem.

Bill had little use for Barlow and his crusty personality and focus on petty issues. Barlow once called him on the carpet for violating company policy by authorizing a car radio for one of his top executives who traveled frequently on company business. “It’s only an $8 radio!” Bill protested.

“That makes no difference,” Barlow fumed. “You violated company policy. Get that radio out of that car.”

Bill came away convinced, “This guy can’t run this company if that’s the way he’s going to act and treat people.” So when J.W. asked Bill what he should do about Barlow, the answer was blunt: “Get rid of him.” J.W. took his son’s counsel with a grain of salt. On the plus side, J.W. viewed Bill as “a fine, accomplished young man,” “fairly religious,” possessed of “an analytical mind,” and a “hard worker,” according to his journal. But he also saw in Bill “lots of fire—impetuous, sincere, inferiority complex. Not too tolerant but improving.”3 In retrospect, Bill said his father’s assessment of him then was fair.

J.W. was not someone who could bring himself to fire anyone, so he hired a consultant to assess Barlow’s future with the company. The consultant said Barlow should never be president, and if he threatened to resign, J.W. should let him. J.W. agonized for weeks while Barlow pressed his case and continued to stumble. Without consulting J.W., Barlow raised the price of Hot Shoppes soft drinks from 10 to 15 cents. J.W. found out only when he visited one of the restaurants. Complaints poured in to headquarters, and J.W. ordered an immediate rollback.

J.W. assigned Barlow to negotiate a partnership with American Motors, and J.W.’s friend AMC President George Romney, to build a hotel on Times Square in New York City. It was Bill, however, who briefed the AMC board and won over most of its members with his detailed report. Barlow subsequently angered enough of the board members that the deal languished and eventually fell apart.

Concurrently, Bill laid the groundwork to buy prime hotel property at the entrance of the Los Angeles Airport. Barlow was dispatched to close the deal, but he didn’t like the price, which Bill knew was a steal. Barlow told the owner he wouldn’t pay that price. “Fine—don’t buy the land,” the seller replied, and sold it to a competitor. Bill continued to fume over Barlow, and J.W. continued to fret. It would be more than a decade before Bill could build a hotel in Los Angeles—and that one was farther away from the airport entrance.

Marriott’s fourth hotel, next to Newark Municipal Airport in New Jersey, was the first that the company bought instead of built. The owner was headed to prison on charges unrelated to the hotel, so Marriott picked it up for the fire-sale price of $690,000 and operated it for seven years until it was sold for a large profit to the federal government to make way for a freeway interchange.

Next up was the Philadelphia City Line hotel, which featured Bill’s first serious tangle with labor unions. The AFL-CIO picketed the construction site just before the grand opening because they had been unable to organize Marriott employees. Former President Eisenhower had promised to cut the ribbon himself at the opening in July 1961, but he canceled rather than cross the picket lines. The unionized construction workers also refused, leaving Bill to scramble family and corporate employees to put on the finishing touches. Barlow put a stove in the kitchen. Dick Marriott assembled tables. Donna’s younger sister Linda, who was visiting that summer, made beds and vacuumed. Bill put down baseboards.

The day before the hotel opening, Allie got a call from the Hotel Utah in Salt Lake City, where her elderly mother, Alice, was a full-time resident. The widow of Apostle and Senator Reed Smoot had been found dead in her room. J.W., Allie, and Dick flew to Salt Lake City while Bill had to stay behind to oversee the grand opening rather than attend his beloved grandmother’s funeral.

That summer of 1961 brought family joys and sorrows. Donna and Bill’s third child and second son, John Willard Marriott III, was born May 4, 1961. Paul Marriott continued his descent into alcoholism, and on May 21 he took an overdose of sleeping pills and went into a coma. When he recovered, he pledged to J.W. that he was a changed man—but by July he was drinking again. J.W. worried that the airline catering customers Paul worked with would lose confidence in Hot Shoppes. Still, though Paul was dragging the In-Flite business down with him, J.W. would not fire him. By August, J.W. was losing sleep over his brother. “He is very depressed and very mad at me. Drove by his house at 7:30 a.m. but couldn’t rouse him. I’m afraid he will take an overdose of sleeping pills.”4

Meanwhile, Bill and Donna had a scare with five-year-old Debbie. She loved riding the ponies at Fairfield Farm, and on May 30, against Allie’s protests, J.W. put Debbie on a horse named Tony. Debbie’s heart murmur worried Donna, but J.W. tut-tutted. “It’s a tame horse, and I’ll be right with her.” Then, as Bill watched in horror, Tony galloped away with Debbie and tossed her off. She hit the ground so hard she was knocked unconscious. Bill ran through the field, scooped her up, and carried her inside to a couch. As they waited anxiously for Debbie to regain consciousness, Allie and Bill lit into Grandpa Marriott.

Debbie’s heart ailment, diagnosed as tetralogy of Fallot, had begun to be more pronounced when she was about two years old and the blue tinge of her fingernails that signified a lack of oxygenated blood appeared intermittently. The Mayo Clinic’s preeminent surgeon, Dr. John Kirklin, recommended surgery. The heart-lung machine necessary for the operation had been used but not perfected, but in 1962, Debbie could wait no longer. One pioneering cardiac surgeon of that era, Dr. Russell M. Nelson (the family friend who would later become President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), described the risk for Debbie. “We didn’t take anybody on for surgery who we thought could live for another year with what they had. We didn’t know what the mortality rates were because we were just starting, so our conscience would allow us only to do patients who were on their way out. If they made it through the surgery, they won. If they didn’t, they were right where they would have been anyway. Every case was a skirmish into the unknown.”5

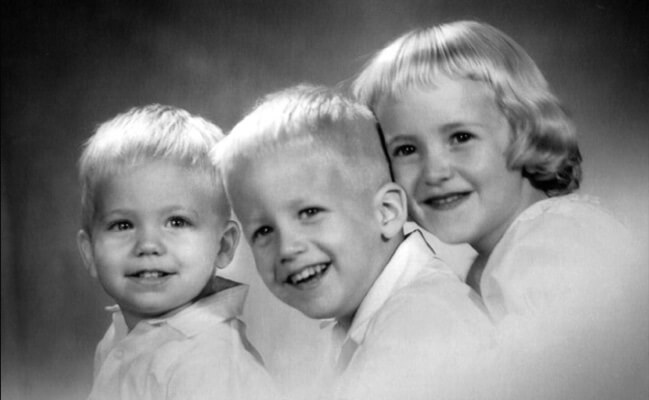

Johnny, Stephen, and Debbie.

The night before Debbie and her parents left for Rochester, Minnesota, and the Mayo Clinic, three-year-old Stephen and eighteen-month-old John got into a fight. Baby John’s ultimate defense was to cry and hold his breath, which he did until he passed out. He fell against the kitchen door, which knocked out one of his teeth. A family friend who was a dentist popped it back in that night, but it came out again and John swallowed it.

Bill, Donna, and Debbie flew to Minnesota on Monday, November 5, where Debbie was then checked into the pediatric ward of the Mayo Clinic’s Saint Mary’s Hospital.

The operation was scheduled for 7:45 a.m. on Thursday. Bill and Donna arrived early that morning to visit with Debbie before she was moved from her “big iron crib.” Bill called it “one of the most difficult moments of our life—seeing her go down that hall to that operation without us.” The one bright spot was that the anesthesiologist, instead of using the cold gurney, picked her up and carried her in his arms all the way into the operating room. The operation lasted nearly four hours. For sixty-four minutes, Debbie was connected to the heart-lung bypass machine through her femoral artery. When Dr. Kirklin opened up her heart, he found that she had only two defects instead of the predicted four. He worked efficiently to repair them.

Many open-heart patients in the 1960s who survived surgery died in the days immediately following the operation. On the second night, Bill and Donna received a terrible phone call in their hotel room. Debbie was not doing well, and might not make it. “We were on our knees all night praying that she might be spared,” Bill recalled.

The medical resident who had been assigned to stay was fortunately there when her heart went into fibrillation. He used CPR and drugs to revive her. He shakily confided to Bill the next day that Debbie appeared to have died for two or three minutes. Neither of her parents knew for more than a decade that Debbie had had an out-of-body experience. It was profound and real to her, but she did not feel comfortable sharing it until Dr. Raymond Moody’s 1975 best-selling book, Life After Life, revealed that others had had similar experiences.

“I remember leaving my body—the room couldn’t hold me,” she said. “I felt a lot older, like an adult, and I knew what was happening—what the doctor was doing to revive me. I had the most wonderful, peaceful feeling. I thought, ‘This is great. I am free from this pain. . . . And I’ve never felt this great love ever before.’ I felt like I had this tractor beam of love pulling me out of that room. I knew instinctively it was the Savior, and that this amazing love was pulling me toward the Savior. I thought, ‘Why do I want to go back there when I can go here?’ I didn’t get as far as ‘seeing the light’ that others talk about, but I was given a choice—not in words, but spirit-to-spirit.”

During that experience, she had a view into her parents’ hotel room, where she saw them praying. “My dad had his head in his hands and he was crying. When I saw that, I said to myself—or out loud, I don’t know—‘I can’t do this to my dad.’ The second I made that decision, I was back in that sick little body, being that sick little girl again. I love my mom dearly; we get along great. But there is something really special about my relationship with my dad. I’ve always felt that part of the reason my life was saved was to help my dad out the best I can while he lives—to be his confidante and his friend.”

Debbie’s brush with death was a turning point in Bill’s life. Developing, building, and managing hotels was all well and good, and those efforts would continue to demand a great deal of his time and energy. But Debbie’s miracle prompted Bill to pledge renewed dedication to his family and a greater consecration of time and talents to God, in and out of the workplace. However, the demands of the corporation were about to test that resolve.

In 1963, J.W. was weary and looking for a way out of the daily grind of directing the family company. In January, he wrote: “Very frustrated with business. Don’t know how long I can take it.” A month later: “Not much peace in this life. Wish I could get rid of all my business.” J.W. thought one of his sons would succeed him, and he had great hopes set on Bill, who was seven years older and more experienced in the company than Dick. But in J.W.’s view, Bill was not yet ready for a promotion, particularly since he hadn’t found a successor to run the hotel division if he rose in the ranks.6

As he had many times before, J.W. turned to a favorite consultant for advice. His name was Harry Vincent, and he would become a critical adviser and close friend to Bill for more than half a century. In 1960, Vincent had reviewed the executive ranks of the company and told J.W. that Milton Barlow was not the successor J.W. was looking for. In 1963 he had not changed his mind. J.W. continued to ruminate for two months until he came to a tentative decision, which he revealed to the board in November 1963: “For much too long, the top management of this company has been lacking in drive and purpose,” he told them. “I’ve been standing to one side hoping that some kind of strong, unified management team would emerge, but it hasn’t. So I’m going to run the company the way it used to be run until we can solve our problem. I’m in charge. I’m the president and chief executive officer. Until further notice, I intend to exercise full control.”

Convinced now that he would never be president, Barlow told J.W. he would like to leave the company “in a year or so.” J.W. was relieved, but he still needed to decide on a new president. In the midst of those company discussions, America was undergoing its own painful presidential transition.

On Friday, November 22, at 12:30 p.m., President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. By early evening, Bill was finally able to connect with Bill Tiefel at the Dallas hotel to get a report. Tiefel had been deployed for six months to oversee the expansion of the hotel. He reported that Dallas hotel personnel were additionally saddened by the murder of the well-liked Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit, who worked as an off-duty security guard at the hotel. Lee Harvey Oswald had shot and killed Tippit forty-five minutes after he shot Kennedy. Also shot was Texas Governor John Connally, whose family was welcomed to stay as long as necessary at the Dallas Marriott Hotel while the governor was treated at a nearby hospital.

One unexpected result of the assassination was its effect on a Las Vegas Del Webb company executive named Jim Durbin. It prompted him to make a career decision that cleared the way for Bill Marriott’s promotion less than two months later.

Durbin had been born in a hotel that his parents owned in Indiana. He grew up learning the business from his parents. The Marriotts got to know him during the eight years he worked at the Hotel Utah in Salt Lake City, where he rose to be assistant manager. He was particularly attentive to Allie’s mother, who lived in the hotel during those years. Bill had tried without success to recruit Durbin. Kennedy’s death and other personal losses left him rethinking his own life. “My wife and I decided not to play it safe anymore. It was time for a change.”

Durbin accepted a job as executive vice president of the hotel division under Bill. When he interviewed in Washington, almost as an afterthought, J.W. asked him to meet with Milt Barlow. That brief meeting killed the deal. “Mr. Barlow didn’t have the warmth or the spark in his eye that Bill and his dad did.” After the interview, Durbin called to tell J.W., “Quite frankly, Mr. Marriott, I can’t work with Mr. Barlow.” Pregnant seconds of silence followed on the phone before Durbin heard an intake of breath and these words: “Don’t worry about that. When you come in February, Mr. Barlow will not be here, and my son will be in his place.”

There was a critical difference in the management styles of Bill and his father. Bill could fire nonperformers with little hesitation. But J.W. was not constitutionally able to fire anyone, no matter how much they deserved it. So, when New Year’s Day 1964 came and went, J.W. had not yet met with Milt Barlow to let him know that he would be replaced by Bill as executive vice president before February. Instead, he hired Harry Vincent to do one more management study. Vincent accepted the assignment even though he had already given J.W. his opinion of Barlow.

On January 6, Vincent met with J.W. to deliver his findings. “It was the unanimous opinion of everyone I interviewed that it would be highly desirable for Bill to be EVP,” Vincent reported. “While I cannot sort out how many were for Bill as much as they were against Milt, I can tell you that all your top people said it would be a great idea and a great change.” J.W. called Board Director Don Mitchell for advice. “You’ve got to let Milt go now,” Mitchell urged.

“I can’t do it,” J.W. responded.

“I’ll do it, then,” Mitchell countered. And he did.

The announcement of Barlow’s resignation and Bill’s promotion was set for Tuesday, January 21, after a board meeting. At four a.m. that day J.W. got out of bed and wrote a list of guidelines for Bill to follow:

Keep physically fit, mentally and spiritually strong;

Guard your habits—bad ones will destroy you;

Pray about every difficult problem;

People are No. 1;

Decisions . . . have all the facts and counsel necessary—then decide and stick to it;

See the good in people and try to develop those qualities;

Manage your time;

Details—Let your staff take care of them;

Think objectively and keep a sense of humor. Make the business fun for you and others.

Since the list was reproduced in a 1977 biography of J.W., some of Bill’s hotel general managers over the years framed the advice and hung it in their offices as a daily reminder. Bill was particularly moved by his father’s letter, and he thought the advice was sound. “I tried to follow it, but it wasn’t my Bible. I didn’t wake up every morning at six a.m. and read it like he told me I should do. I did the best I could.”

Bill hit the ground running as executive vice president. He had to. For two months, J.W. was absent from the office—laid low with both a gastric ulcer and an ear infection that nearly cost him his hearing. During those two months when Bill was effectively head of the company, not once did J.W. fret in his journal about Bill’s performance. Instead, he was uncharacteristically effusive in his praise for his son. For himself, Bill was not filled with confidence. He was just thirty-one, and he had a lot to learn about the non-hotel portions of the business.

By April, J.W. was on the mend enough to put in an inspiring performance at Brigham Young University. The men’s student association had tapped him to receive its Exemplary Manhood Award. J.W. worked for more than a month on his speech. A dozen students, including young Jeffrey R. Holland and his new wife, Patricia, prepared a skit reviewing J.W.’s business career. (Holland later became president of BYU.)

Holland related the fiasco that followed: “The hour came and J. Willard came. But not a single student appeared.” The sponsors had forgotten to publicize the event, and the cavernous basketball arena was empty. “Now here is the part that matters, and which I will never forget as long as I live,” Holland continued. “Mr. Marriott said to the very red-faced and totally distraught young sponsor of this event, ‘Let’s begin.’” The student stammered and said, “No one is here.” To which J.W. replied, “You are here and I’m here and these kids in this skit are here, let’s begin.” Holland finished the story:

So to an absolutely empty fieldhouse—as dark and void as the world before creation—J. Willard watched the skit, laughed, and applauded on cue, and accepted the honestly and lovingly awarded plaque.

Then he spoke. He spoke to the 12 or 15 of us in the skit, plus the 3 or 4 student sponsors, and a few others who had come in, friends of friends. As we all hurried out to sit on the front row, before an absolutely barren podium, save for the dignified and beautiful image—the standing figure of J. Willard Marriott.

[He] gave that night one of the most stirring and heartfelt talks that that little handful of students had ever heard. His topic was: “Think, Work, Pray.” I remember the message to this day.

But what I especially remember was the dignity and the grandeur, and the absolute unequivocal Christian compassion that a very important man demonstrated to some very chagrined students. He could have been angry. He could have sulked. He could have exploded. He could have stormed out of the building. He could have reminded everyone of how demanding his schedule was and how far he had traveled, and how monumentally offensive such an experience was. All of that was absolutely true. . . .

But he did not speak one word of any of it. Regardless of how much he may have felt like doing it, he did not do any of it. He spoke as if the whole world were present. And he acted as if this was the greatest compliment and the highest award he could ever be given. It was simply one of the most profound demonstrations of compassion and humility I have ever seen in my life.7

Another family member was also gathering accolades that summer. Allie was rising in the ranks of the national Republican Party, becoming the first woman to serve as treasurer for the party’s national convention. During the convention in July in San Francisco, the press lauded her as “cool and competent” amidst the pomp and chaos. She had to sign every check—from $3.50 for staples to $35,000 for the use of the Cow Palace convention hall. Arthritis pain in her right hand became significant as she worked through all the banking. Outside the family, no one knew of her struggle.

The convention itself, which saw the nomination of conservative Senator Barry Goldwater, was otherwise an unpleasant experience for the Marriotts. Goldwater fractured the party, leading to the landslide victory of Lyndon Johnson in November.

With each passing week that summer and fall of 1964, J.W. stepped further back from control of the company. Bill was riding a wave of success, and he used it to persuade J.W. that it was time the company became part of the New York Stock Exchange. And if it did, then the company’s name would need to change, since it was becoming more identified with the Marriott hotels than Hot Shoppes restaurants. A name change would cause confusion, J.W. argued, so Bill proposed and J.W. approved an intermediate moniker, “Marriott-Hot Shoppes, Inc.”

Though he had made a few missteps, Bill’s swift growth in the EVP job and widely acknowledged leadership success prompted board member Don Mitchell to persistently pose a question to J.W. throughout October: “Is there any good reason to wait any longer to make Bill the president?” J.W. could not come up with one.

J.W. Marriott, chairman, and Bill Marriott, president.

As chairman of the board and CEO, J.W. would still have ultimate control of the company, but he warmed to the idea of letting go of the day-to-day responsibilities. He made the decision; he would step away as president during the November 10 annual shareholders’ meeting and nominate his thirty-two-year-old son to take his place. Asked by a reporter later what it was like to turn his life’s work over to his son, J.W. replied: “Great—it was the greatest thrill I’ve ever had. Besides, I didn’t want to work so hard anymore.”8

The shareholders’ meeting was held at the Twin Bridges Marriott. First, the shareholders approved the change in the company name to Marriott-Hot Shoppes, Inc. Then, a beaming and emotional J.W. stood up to read a short, prepared statement that would change the company forever:

For nearly four decades, I have headed our company’s operations, and—with the help of many dedicated, talented people—I have been privileged to see the business grow from a small root beer stand to a major national chain with annual sales which are now approaching the $90 million level.

I feel it is my responsibility to shareholders to turn over the active management of the company to a younger man.

Our Board of Directors feels that the outstanding job done by J. W. Marriott, Jr., both as executive vice president of Marriott-Hot Shoppes and as president of our Marriott Motor Hotels Division has qualified him to assume the responsibilities of president of the corporation.

However, I expect to be around for a long time as Chairman of the Board to assist in every way I can to be helpful to the continued growth and development of our company.

From the podium, J.W. looked down into the hundreds of upturned faces. Attendants stood by in the aisles with portable microphones for stockholders wishing to ask questions or offer opinions.

“Any discussion?” J.W. asked. The attendants scanned the audience; no one moved.

“All in favor raise your right hands.”

Every right hand in the audience went up. Some raised both hands. On the platform where the corporate officers sat, everyone stood up. The stockholders broke into cheers. Arms outstretched, J.W. and Allie surrounded their son.9