Chapter 10

Midway Airport had been Chicago’s primary airport for more than a decade when J.W. built an in-flight catering kitchen there in 1956. Six years later, when all commercial traffic was shifted to O’Hare Airport, Marriott followed, building a kitchen just for its American Airlines contract. When Bill inspected the new kitchen, he resolved to build a hotel next to what was then the world’s busiest airport.

It may be hard for readers in the twenty-first century to realize that there was a time when the Marriott name was not known in most of America, much less the world. After the ground breaking for a Marriott in Chicago in 1966, advertising man Aaron Cushman heard about the planned hotel and asked around, “What’s a Marriott?” No one seemed to know, Cushman wrote in his memoir. “The best answer I could get was that they were a tiny company headquartered somewhere in the East.”

Bill hired Cushman, who visited the company’s Maryland headquarters and began to work closely with Marriott’s team in Chicago. The jaded Chicago ad man became a Marriott convert. “They had some very unusual characteristics. These people really cared. They were motivated like no one I had ever met before—they were a different breed of cat. They loved what they were doing and absolutely ignored the hours they poured into the job.”

Cushman and his firm worked hard to successfully secure daily mentions or photos of the Marriott hotel project, but Bill balked at his plans for grand opening stunts. “After investing millions of dollars, I don’t understand why I can’t just open the door and walk in—or routinely cut a ribbon,” Bill complained to Cushman during a Chicago taxi ride.

“You could do that,” Cushman allowed, “but you won’t get more than a couple of columns on the real estate page. We need to excite the newsmen to leave their downtown desks and get us a photograph on the front or back page of every daily paper and 30 seconds of TV footage on the evening news.”1

Bill approved the plans, and it worked. For the December 1967 opening of Marriott’s eighth hotel, voluptuous beauties dressed as mermaids surrounded the ribbon cutters next to a then-novel year-round indoor-outdoor pool. A giant six-foot replica of a hotel key was inserted into a twelve-foot mock-up of the real main entrance, then hoisted aloft by helicopter and symbolically dropped into Lake Michigan, signifying Marriott’s permanent open-door policy.

Prior to the grand opening, when the hotel advertised for job seekers, more than 2,000 people showed up, forming a line around the hotel more than a block long. Among the hopeful applicants was a blind man, John McDonald, a father of four. He had already applied to and been rejected by more than fifty companies. Marriott hired him to be a silverware sorter in the hotel kitchen. He surprised everyone with his rapid and efficient sorting.

In a 1982 speech, Bill fondly related: “Whenever I can, I like to visit our hotel at O’Hare Airport in Chicago. Each time I do, I enjoy chatting with John. [He] has a perfect attendance record—no easy task because he has to get up at 4:30 a.m. to catch a bus each working day. That dish room is one of the best in our company. John always has a big smile, and constantly inspires others with his diligence, enthusiasm, and hard work. He’s been a great motivator for me personally. Sometimes when I’m on the run and I ask myself if all the hassle is worth it, I think of John in Chicago, cheerfully sorting silver that he will never see. So I go ahead with the task at hand.”2

At the same time that Bill was building new hotels, he was also adding rooms to his older hotels. When it came to a projected twelve-story tower at Key Bridge, he found himself in the middle of a heated environmental controversy—even as Lady Bird Johnson was praising his support of her beautification initiative.

The First Lady was a fan of Hot Shoppes because her two daughters were. One of Luci Johnson’s close friends was a waitress at the Twin Bridges restaurant, so she frequently stopped in for a Mighty Mo hamburger and chocolate milkshake. When sister Lynda wanted to have a private talk with her mom, she persuaded Lady Bird to go to a Hot Shoppe drive-in for lunch in a nondescript car. Newspaper columnist Betty Beale wrote of such outings: “This is the most private way that the mother and daughter can eat together without being disturbed by telephone calls or any of the other frequent White House interruptions.”3

Lady Bird also appreciated the landscaping Marriott had donated for the traffic circle in front of the Key Bridge hotel, and she wrote to tell Bill so: “How generous you have been to give so much beauty to the Rosslyn circle area of this city!” she said in a June 1966 letter.

Only a few months later, an Arlington, Virginia, citizens group protested what they considered to be Marriott’s unsightly plans to add the twelve-story tower at Key Bridge, raising the existing two large neon Marriott signs to the top. The Arlington County Planning Commission had approved the plans and refused to back down, even after Senator Bobby Kennedy and Interior Secretary Stewart Udall entered the fray. Udall derided Marriott’s plans for a “garish commercial intrusion” to the Potomac riverfront. Intent on being a good neighbor, Bill wrote Secretary Udall that he would reconsider the matter. The company would “endeavor to do whatever it can to cooperate with you.”

A few weeks later, the First Lady invited Bill and Donna for a bus tour and White House luncheon that would focus on her beautification efforts in the capital city. Bill and Donna were featured in an accompanying photograph as they examined a model of a proposed public school amphitheater. “Bill Marriott says he feels peculiar going to the White House for lunch when he still hasn’t changed his mind about putting a 14 by 47 foot neon sign atop the addition to the Key Bridge Marriott,” one article noted.4

By the time Bill opened the addition in 1970, he had muted the controversy by shrinking the size of the sign and dimming the neon. In time, even that twelve-story building would be dwarfed by other high-rise buildings, including the prominent USA Today-Gannett twin towers.

One of Bill’s prime goals as company president was to qualify the company for a prestigious listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The path to the listing began in April 1965, when the board of directors approved a 2-for-1 stock split, increasing the total number of shares from roughly two to four million and doubling the number of shares Marriott family members held.

To qualify for the NYSE listing, lawyers and brokers advised Bill and J.W. that the family would have to shed the family-owned real estate companies that leased properties to Marriott-Hot Shoppes (MHS) for hotel and restaurant operations. Neither Bill nor J.W. wanted to spend any MHS capital to buy the real estate companies from the family. Instead, they traded the companies for 249,669 more shares of MHS stock, which substantially increased their holdings a second time. After that, Bill and J.W. thought the family was holding too many shares. So the family put up 500,000 shares in a “secondary stock offering.” That still left J.W. and Allie owning nearly 11 percent of the company, and Bill, 7.49 percent. The sale netted J.W. and Allie $3.8 million each. The checks for Bill’s three uncles ranged from $1 million to nearly $3 million. Having sold the least amount of stock, Bill received a check for $1,009,375. At the age of thirty-four, he had officially become a cash millionaire, though on paper his net worth had already exceeded that amount.

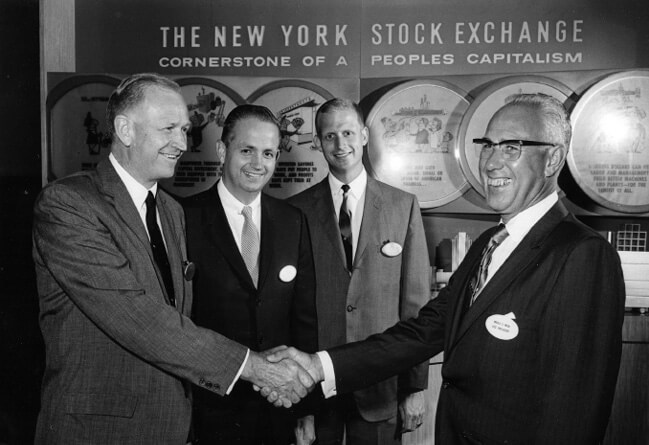

Celebrating the listing of Marriott-Hot Shoppes on the New York Stock Exchange.

Just before the NYSE listing, Bill split the Marriott stock 2-for-1 for the third time in less than eight years. On August 26, 1968, Bill, Donna, J.W., and Allie flew to New York City and proudly stood on the VIP balcony when the opening bell rang and their stock—under the tickertape symbol “MHS”—began to sell at 32¾ a share. Bill and J.W. each purchased 100 Marriott shares to kick off the trading.

Because Bill was running the company so well, J.W. had plenty of time in the second half of the 1960s to focus on several projects for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the most important of which was the need for a temple in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill concurred wholeheartedly and assisted where he could.

The last time there had been a Latter-day Saint temple east of the Mississippi, it was in Nauvoo, Illinois, and that had been destroyed by arsonists more than a century earlier. On frequent occasions, when J.W. hosted visiting Church leaders, he would take them to several locations that he and other local Church members thought would be good sites for a temple. The tour always ended at the most favored site, in the suburb of Kensington, Maryland—a wooded hill overlooking the Capital Beltway. In 1962, President McKay finally approved the purchase.

One concern for the conservative Church leadership was the explosive Civil Rights movement, in which the nation’s capital was the target of protests and riots. The fervent hopes of the Marriotts and other area Church members seemed to be dashed when Washington, D.C., erupted in six days of rioting following the April 1968 assassination of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Bill’s younger brother, Dick, vividly recalled those dark days because he was managing the Langley Park Hot Shoppe. “I remember walking out of the front door on Friday, wondering why we did not have many customers, and then seeing a row of tanks coming down the street. There were big clouds of black smoke in the distance. . . . We were wondering what was going to happen, because we were on the outskirts of a predominantly black neighborhood. We were not sure if we were going to get burned. But we had a lot of wonderful people working at the Hot Shoppes—both black and white.”

Local Church leaders responded with compassion. When D.C. Mayor Walter Washington asked for emergency assistance for tens of thousands of victims, the Latter-day Saints responded with what the mayor called the best-organized relief program in the city. Bill himself dispatched dozens of Hot Shoppes trucks with relief donations, including an estimated 185,000 meals. Just weeks after the riots, Apostle Harold B. Lee traveled to Washington on other business and, alarmed by the devastation and unrest, advised the Marriotts that a temple in Washington would have to wait.

J.W. couldn’t wait. Two months after Washington burned, Church leaders asked J.W. if he would consider moving to Salt Lake City to accept a “big job in the Church,” meaning a full-time leadership calling. “I [said] I couldn’t handle [the] job with responsibility because of my heart trouble—but would give $500,000 for a temple in Washington.”5 It was classic J. Willard Marriott; he changed the subject and offered the Church a huge incentive to proceed with the family’s most desired project. The persistent campaign worked. Incredibly, only seven months after the city was in flames, President McKay made the announcement that the Church, which had been founded by New England men and women, would symbolically return to the East with a temple in Washington, D.C. The ground-breaking ceremony that the Marriott family attended that December was a very happy day.

On matters spiritual and personal, the Marriotts were united and loyal. But that harmony often ended at the office door. Disputes between father and son reverberated around the extended family.

The strong-willed and protective Donna Marriott was never going to be her father-in-law’s favorite, and she was fine with that. She became a gatekeeper at times for Bill. Sometimes, when the father and son had a conflict at the office, J.W. would try to continue the argument over the phone, interrupting Bill’s dinner or family time. Donna would refuse to put Bill on the phone. His father had hounded her husband enough for the day, she said, and she wasn’t going to put him through. On a few occasions, when it got particularly acrimonious, Donna would call and ask Allie to intervene, occasionally dangling the possibility that Bill could easily quit the company, start his own business, and leave the aging J.W. in the lurch.

J.W.’s feelings toward his son and corporate heir were deeply complex. He was proud, and yet deep down he had to know that Bill had set the company on a profitable trajectory that J.W. himself had neither the will nor the vision to do. Often, after Bill received attention or praise in the media, J.W. would pick a fight.

Bill became sensitized to that reality, and, when it was possible, he put his father front and center at events such as hotel grand openings. J.W. enjoyed the limelight and Bill did not, so that worked for both. When J.W. opposed one of Bill’s ideas, if Bill waited long enough, J.W. would generally come around and even praise him.

As happens with many aging company founders, J.W. also wrestled with feelings of increasing irrelevance. His expertise was food service, but that industry had a narrow profit margin, while hotel development, with its more substantial growth possibilities, was clearly the wave of the company’s future. In that field, Bill had superior knowledge and skill. “My father didn’t understand the hotel business, but he thought he did,” Bill said. If it appeared that Bill wasn’t listening to his advice about the hotels, a frustrated J.W. became louder and more acrimonious. “Talked business with Bill 20 minutes & bad feelings,” he wrote in his journal. “I better stay away from business. I shouldn’t criticize but I never could tell Bill anything. Guess I’m not diplomatic.”6

It didn’t help that as the company moved forward in the latter part of the twentieth century, J.W.’s mindset was still stuck in the Depression, when hotels failed and when debt began to haunt J.W. like a specter. Friends and family—including Bill—often blamed the sometimes-prickly relationship between father and son on their disagreement over corporate debt. But, as with anything else involving human personalities and a shared family past, there was more to it. Bill’s son John, who loved both of them, offered frank insight:

“My dad doesn’t vacillate. He decides. My grandfather liked to talk through every decision, worrying about whether it was right or not. Actually, he liked to argue about everything, and my dad didn’t. My dad’s very sensitive, and he doesn’t like to be criticized. Nobody likes to be criticized, but he really doesn’t like to be criticized. Sometimes he takes suggestions or ideas as personal criticism, when they aren’t meant that way. Now add in his own father, who often intended to criticize my dad. So my grandfather would push his buttons, and dad would go nuts.”

This relationship dynamic came to a head on J.W.’s sixty-eighth birthday. After a sleepless night worrying over Bill’s hotel expansion plans, J.W. went to the office that day and let Bill have it. It was worse than any previous tirade Bill had endured, so he left the office early, very upset. “He was shaking so much, I thought he was going to have a heart attack,” Donna said. A birthday party was planned that night at J.W.’s, but Bill refused to go. J.W. called to apologize. “I wouldn’t let him talk to Bill,” Donna recalled. “I said, ‘You’re killing him! You’ve got to leave him alone.’”

Later that night, J.W. penned a self-aware journal entry:

Thought of my shortcomings.

The rate at which Bill is going with the business—he signed deals today on large convention hotels, New Orleans, 42 stories, $28 million, and Los Angeles Airport, $25 million. And we are still looking for locations—adding to six present hotels & six more we haven’t finished building.

I remember when all big hotels went bankrupt in the ’30s. I’m a coward I guess. Don’t like debt. No peace with the creditors breathing down your neck.

Still, we are going great now. Bill doing a marvelous job with his team of tigers. I only discourage him. I really should step out & let him go his way—only a weight around his neck.

I lost my temper today with Bill & it made me sick. Gave me a bad headache—which I can’t afford. Bill was so depressed & sick he didn’t come to my birthday dinner, which made me feel worse.

But I am 68 today & I suppose too old to change—to go at Bill’s speed. I am a [propeller-driven] DC-3 vintage. He is a 707 jet.7

Two months later, J.W. was offered a diversion. Richard Nixon had been elected president and wanted J.W. to chair his 1969 inaugural festivities. J.W. accepted the post at once, having known Nixon since the 1940s. Bill was elated. The job was a big boost for his dad, whose doldrums evaporated with the prospect of being part of national history. “I was happy to see him divert his energies away from the company, because he was at that time more of a hindrance than a help,” Bill said.

Bill and Donna felt duty-bound to attend several inaugural events, in addition to hosting parties for airline executives and others on behalf of the company. Bill’s heart swelled with particular pride, though, when he saw his parents sitting behind the Nixons during the swearing-in, and then leading the parade to the White House in the first car, a top-down convertible, with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir not far behind. At a cost of $2.85 million, it was the most expensive inauguration yet—but the bill was entirely covered by private donations and the sale of tickets and souvenirs. Proving J.W. was a captain of private enterprise, the inaugural committee ended up with a surplus of $1,016,000. Throughout the next year, in consultation with First Lady Pat Nixon, J.W. parceled the profits out to worthy civic projects.

While J.W. was diverted by the inauguration, Bill was busy establishing a Marriott presence in New York City, buying and remodeling the venerable old Essex Hotel in the heart of midtown Manhattan along the south border of Central Park. The renamed Marriott Essex House opened in April 1969. In the same way that Conrad Hilton elevated his profile when he bought the Waldorf Astoria, so too did the purchase of the Essex House raise the stature of Marriott’s hotel operations.

As part of the deal, Marriott inherited a unionized workforce. Marriott executives estimated that the hotel had about a third more staff than they actually needed—a featherbedding situation that was a source of ongoing frustration for Bill. He explained to Forbes magazine: “At the Essex House, a dishwasher can only wash dishes and a glass-washer [must wash] glasses. The broiler cook cannot cook with the deep-fat fryer. We don’t have this in other places. A salad girl can work the salad block for an hour, then turn around to the sandwich block. And if she wants to be a cashier, we’ll give her a crack at it, or at being a hostess.”8 Instead of serving their members well, the unions prevented the Essex staff from having the easy upward mobility that occurred in the rest of the Marriott company.

Less than a month after taking over the Essex, Bill took over management of his eleventh hotel, his first outside the United States. It was Acapulco’s newest and tallest hotel, the beachfront Acapulco Marriott Paraiso del Pacifico, built by a Mexican millionaire and managed by Marriott. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Acapulco had been a playground for the wealthy, but by the late 1960s, the Paraiso was able to capitalize on a new accessibility to middle-class Mexicans and Americans.

None of Bill’s previous hotels proved as difficult or frustrating as his twelfth, which was eight years in the making. In 1961, when Bill had first wanted to build in Boston, he had rejected an expensive downtown location in favor of the Newton suburb. It was a beautiful spot, formerly a park, and Bill wasn’t the only one who thought so. But a small group of dedicated Newtonian preservationists rose in protest. Bill had not anticipated any zoning problems and was surprised by the zeal of the local opponents, who delayed the project more than four years, fighting a legal battle all the way to the Superior Court of Massachusetts. Marriott won the case and broke ground in 1967.

For the next two years, J.W. fretted about the $10-million construction price tag and worried over many details. Harry Vincent recalled, “To build the Marriott in Boston at the cost being considered meant you had to have a $100 room rate, which was unheard of when the project began. No hotel could ever command a $100 per room rate, and it was very hard for Bill’s father to break out of that mindset, so he resisted that project.” The hotel opened with a $125-a-night rate and boasted better than 80 percent occupancy, becoming one of the most reliable stars of the Marriott chain.

Vincent concluded: “J.W. was a wonderful, attentive, conscientious, dedicated person—but not a risk taker. It is absolutely clear to me that the performance of the Marriott corporation in growth, profits, and return to the shareholders has been many-fold more effective under Bill, Jr., than it was or would have been under his father.”

A common misperception—even within the Marriott corporation—is that Bill spent most of his time on hotel development after becoming president in 1964. Yet at the time the company was primarily a food-service business. The Hot Shoppe restaurants, Big Boy coffee shops, Roy Rogers fast food outlets, industrial cafeterias, and in-flight catering made up more than two-thirds of the corporate profits. Out of necessity, Bill threw himself into the struggling airline catering business, which provided a third of the company’s income.

Because of Uncle Paul Marriott’s spotty management, when Bill took over airline catering it was losing $100,000 a year. He discerned early that the best way to beat his competitors was to infuse large amounts of capital for kitchens and to take risks. The contracts with airlines were notoriously breakable. For example, in Bill’s first summer as president, Northwest Airlines canceled an agreement with Marriott. “We have just built a $500,000 kitchen and before we get in it, they cancel!” J.W. lamented in his journal.9 No caterer could win an exclusive agreement to service an entire airline because no caterer had a kitchen to provide fresh food at every one of the airline’s airport stops.

Bill felt the greatest potential for airline catering growth was not in the U.S., but overseas. Less than a year after becoming president, he bought Cervesio Catering, which had a monopoly at the Caracas, Venezuela, airport. It was Bill’s first experience with foreign employees, and a rocky one at that. He had been impressed with Cervesio’s 40 percent profit margin, but then learned that some of that profit came from questionable practices. “They were taking trays off the incoming flights and reusing the food that wasn’t eaten. If there was a dessert or a salad that hadn’t been touched, they’d stick them on the outgoing flight. We had to put a stop to that.” Bill’s next overseas acquisition was a Puerto Rican airline caterer. Then he expanded to Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain.

The fact that Bill correctly foresaw and prepared for the coming age of jumbo jets gave the company a big head start in servicing them. With the ability to carry more than 360 passengers, the Boeing 747 was going to change the way Marriott In-Flite did things. In short, they would have to meet the challenge of putting together the biggest carry-out operation in the world every time they serviced a 747 flight. He needed more storage and bigger kitchens full of labor-saving devices, and he needed them now. So his team fast-tracked a ninety-day build model that could be reproduced at any airport.

The last big hurdle was devising a truck that could deliver the food modules by hydraulic lifts to the galley doors of the towering 747s. Trucks on the market that might do the job cost $25,000 each, which was too expensive, and they weren’t specifically made to off-load food crates. Marriott needed to design and produce its own fleet of special trucks. One day, Bill Martin, director of In-Flite’s construction and maintenance, was driving down an expressway behind an American Linen truck. He saw dirty laundry stored on the roof, away from the clean linen in the trailer. Eureka! At only $15,500 each, Marriott soon had a truck with a back elevator and a wider deck that permitted efficient loading across the roof of the deck.

Pan American Airways launched the first 747 service route in the United States on February 4, 1969, from the San Juan airport. That day, Marriott became the first independent airline caterer to supply a 747. Marriott quickly established a reputation as the fastest and most efficient jumbo jet supplier, and the contracts multiplied rapidly. Marriott’s In-Flite division also became the first caterer for the Auto-Train food service between Florida and Virginia.

After a decade of hard work and close attention to the In-Flite Division, Bill had produced significant results. He had secured one-quarter of the domestic market. By the end of 1974, he had made significant inroads into Europe, adding London and Frankfurt kitchens. In Africa and Asia, he had opened facilities in Johannesburg and Guam. Bill had clearly launched In-Flite on a path that would soon make it the largest and most dominant airline caterer in the world.

Bill’s business expansion required him to hobnob with government agencies and politicians, but, unlike his father, he kept a professional distance. Nixon made Bill a member of the president’s Advisory Council for Minority Enterprise based on Marriott’s own much-praised program for advancing minority employees up the corporate ladder. Bill took the advisory council position seriously and used it to lobby the president for breaks for minority business owners.

The president only “lobbied” the Marriotts once. In a private meeting in the Oval Office, Nixon asked the Marriotts to hire and keep an eye on his younger brother, Donald. He was an inveterate wheeler-dealer with a penchant for embarrassing his brother. Though the Marriott name does not appear on the president’s official schedule for that day in December 1969, Bill later confided details of the meeting to friend and syndicated columnist Jack Anderson. Anderson summarized it thus: “Delicately, the President asked the Marriotts to keep his brother out of trouble. ‘I want to be sure that Don has no dealings with the federal government,’ said the President. ‘I want to be sure that Don is never asked to do anything that would embarrass this office.’ Then the President added as an afterthought: ‘Don is the best salesman in the Nixon family.’ The Marriotts agreed to watch over Donald.”10

Bill was actually amenable to the hire. Several years before, one national airline had inexplicably dropped a Dulles Airport in-flight catering account with Marriott, and Bill asked why. Was it dissatisfaction with Marriott service or pricing? Bill asked one of the airline’s executives. “No,” the airline executive confided. “It was Donald Nixon. He came to see us on behalf of his client (a Marriott competitor). We suspect that someday his brother is going to be President of the United States, and we decided to go with him because we needed that relationship.” So Bill thought that hiring Don might be able to bring the Marriott company new business. And, in fact, Don soon brought that national airline account at Dulles back to Marriott.

In early 1970, Nixon asked J.W. to form an “Honor America Committee” for Independence Day. The stated purpose was patriotism, but Nixon was really looking for a way the “Silent Majority” could mount a rally to counter anti–Vietnam War demonstrations that were plaguing his administration. For five weeks, Bill didn’t see his father at the office while J.W. planned the patriotic event, which included the Reverend Billy Graham and comedian Bob Hope, both of whom became close friends of the Marriott family. A crowd of 450,000 showed up on the Fourth, but Bill and his family were not among them. He was in the hospital recovering from an emergency hernia operation.

The media frequently referred to the Nixons and senior Marriotts as “good friends.” During Nixon’s presidency, he invited J.W. to White House meetings or dinners on twenty-one occasions, and to another fourteen presidential events outside the White House. Contrary to appearances, however, they were not real friends. J.W. admired Nixon and backed his political initiatives, and Nixon appreciated J.W.’s loyalty and support. But it was a professional acquaintance, not a friendship.

The main Nixon administration official whom J.W. and Allie actively cultivated as a friend was Attorney General John Mitchell, along with his garrulous wife, Martha. The Marriotts invited them to a warm winter vacation at Camelback in February 1971. The following Thanksgiving, the Mitchells were invited to dinner at the Marriott farm in Virginia. A snowstorm kept Bill and Donna away that day but also allowed Bill to keep the Nixon cabal at arm’s length. It was not that he was prescient enough to anticipate trouble. He was simply too busy to hobnob, and he remembered that the one time his father had asked President Eisenhower for a business favor, it had gone badly.

Though Allie did not need or pursue Republican political assignments, she was in the thick of it with J.W. She was tapped to be treasurer of three successive Republican national conventions—1964, 1968, and 1972—and she was also a longtime Republican National Committee (RNC) representative from the District of Columbia and rose to be an RNC vice chairman during the Nixon administration. In terms of generational impact, however, Allie’s longest-lasting public contribution was to help guide the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts from its founding to its full flowering as its advisory committee chair, appointed by Nixon.

While J.W. and Allie enjoyed the regard of the president, Bill was dealing with the negative fallout of employing Nixon’s younger brother. On Sunday, January 30, 1972, after church, fellow Latter-day Saint congregant and friend Jack Anderson, the highly prominent journalist, took J.W. aside and told him he (Anderson) was on the verge of publishing a series of hard-hitting stories on Don. J.W. conferred with Bill, and both thought it might be a good idea to have Don fly to Washington from his California home and meet with Anderson to answer questions.

The next day, J.W. called Nixon aide John Ehrlichman to warn him, which set off a presidential panic. Nixon hated Anderson because of his scoops on Nixon shenanigans, which had won Anderson a Pulitzer Prize and put him at the top of Nixon’s infamous “Enemies List.”

As heard on the White House tapes, Nixon spent hours obsessively discussing Anderson, Don, and the Marriotts. “The older Marriott claims to have some kind of influence with Anderson,” Ehrlichman reported. He advised that Nixon not get personally involved with his brother’s troubles. “He just has so many flies on him right now that you shouldn’t get into it.” Ehrlichman called J.W. and asked for help with Anderson to soften the upcoming Don Nixon stories as much as possible. A week later, Anderson published his columns on Don. Even Nixon was astonished that Anderson, with a bow to his friends, absolved the Marriott corporation and President Nixon of Don’s questionable-but-not-criminal wheeling and dealing.

What neither the president nor J.W. knew was that Anderson had uncovered a much bigger story involving Don and a potentially criminal business deal in the Pacific area. Because Anderson thought that J.W. would tell the White House, he provided the details only to Bill. “I’ve got the goods on him, but he works for you and it will probably hurt your company even though you aren’t involved.” After Jack laid out the specifics, Bill asked him not to publish the more damaging story. “Please, as a favor to me and my dad, don’t run it,” he recalled asking.

Jack Anderson rarely passed up a scoop of that political magnitude. He went through several hours of soul-searching, considering not only his friendship with the Marriotts but also his respect for Bill’s integrity. Finally, with resignation, he called Bill and promised not to run the blockbuster. “It was a big deal,” Bill recalled. “I knew it was a really big deal for Jack to do this. We never forgot that kindness.”

While Bill steered clear of the Nixon administration, he had a hint of the chaos through the eyes of his close friend Jon Huntsman, whom he knew from Church association as well as from Huntsman’s marriage to Karen Haight, sister of Bill’s best man, Bruce. As the Watergate scandal unfolded, Huntsman was trying to tactfully ease his way out of the White House, where he was serving as Nixon’s special assistant and staff secretary, taking a detour from building his own corporate empire.

Bill once described Huntsman as a true friend, “one you can count on in any situation. When you’re up or down, happy or sad, he is the one who listens and understands and who asks nothing in return but your friendship.”11

They were two friends who were also not above pranking each other. In the summer of 1972, Huntsman, newly freed from the White House job, took a vacation with the Marriotts at Lake Winnipesaukee. They had taken their families in two station wagons to an outdoor pageant in Palmyra, New York. Bill had combined the trip with a stop to inspect the new Rochester Marriott, and both families had left with fruit baskets from their overnight stay. The caravan of station wagons was at a stoplight in Bennington, Vermont, when Huntsman leaned out of his window and lobbed an overripe peach into Bill’s windshield. Bill returned fire. “We held up traffic through two light changes with one of the best fruit fights you’ve ever seen. The cars were a mess, and so was the town,” Bill recalled. “It’s a wonder we both didn’t land in jail!”

A year later, as the Watergate scandal exploded, both Huntsman and the Marriotts came to realize just how close they had innocently come to getting dragged into the morass. As the indictments of Nixon’s top aides rolled forward, J.W., Bill, and Jon met on May 19, 1973, to discuss the unfolding events. The attitude for all was, “there but for the grace of God go we.”

Huntsman confidentially related to the Marriotts how he had almost been pulled unwittingly into the middle of Watergate. Shortly before he resigned, Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman instructed Jon to solicit a $100,000 cash campaign contribution from Jon’s former employer, Dudley Swim. Swim and his wife were both from Twin Falls, Idaho, and she was a Latter-day Saint convert. The Marriotts were also longtime friends of the Swims, partly because Bill had frequent business with Dudley, who was chairman of the board for National Airlines, an In-Flite customer.

Haldeman pledged that Swim would be made ambassador to Australia if he ponied up the money. Making ambassadors of major campaign contributors is a routine presidential practice, but the cash donation was out of the ordinary. Swim agreed to the contribution, but he wanted to write a check. Haldeman said no, and Swim reluctantly agreed. Jon explained to the Marriotts that it was not until the Watergate revelations that he realized the Swim donation would have been part of the secret slush fund used to pay for illegal campaign operations.

Huntsman actually made the airline reservations to pick up the money from Swim at his California home. The day before the flight, Dudley Swim unexpectedly died of a heart attack. “His passing saved me from becoming an unwitting bagman in an illegal contribution scheme,” Huntsman confided to the Marriotts. J.W., feeling a bit queasy, wiped his own forehead. All J.W.’s campaign contributions were by check, but if a Nixon aide had ever asked him for cash, he realized he might have given it, assuming it was a legal request. If he had done that, how quickly all those years of Marriott reputation building would have been undone!12