Chapter 18

Bill Marriott was alone at the top of his company, and never before had the responsibility of its future weighed so heavily. He had good employees and a superior management team, but in the first two weeks of that fateful August 1985, he lost three important players upon whom he’d come to depend—his father, his brother, and Gary Wilson.

Technically, Wilson was the CFO until September 3, but he had already moved to Los Angeles, having been hired by Michael Eisner as Disney’s new CFO. Wilson and Al Checchi (who had left three years earlier) had been the financial wizards who—through inventive limited partnerships, stock buybacks, and other creative maneuvers—had been critical to Marriott’s growth. J.W. never fully trusted Gary’s financial wizardry, which hadn’t made Gary appreciative of the obstreperous Chairman.

The funeral, however, changed Wilson’s view of the formerly fearsome man. In a note to Bill, he said, “Unfortunately for me, I saw The Chairman principally from an adversarial business vantage point and not as the wonderful family man that he obviously was. I know you had disagreements with The Chairman over company matters but, unlike the rest of us, you saw the warm, religious family man that he really was. . . . He lived a fine life and his final day was truly wonderful, with his entire family present. May God rest his soul.”1

Wilson had been a front-row witness to the ongoing bouts between father and son, and he had stayed firmly in Bill’s corner, supplying the encouragement and strategy needed to win the struggle for the company’s future. Now the final bell had rung, and the seemingly endless contest between the company’s founder and its builder was over. Yet, in all those years, Bill never doubted that his father wanted the best for him, even if they didn’t agree on what that was.

J.W.’s death took away the friction for Bill, according to Donna. “Bill was always on edge knowing that no matter what he did, his dad might not approve. Now that was gone.” Yet the responsibility he felt for the company and its employees weighed heavy. For two decades since becoming president, Bill had worked sixty to eighty hours a week, sacrificing time, family, and health, to grow the company. Over those years, Marriott had grown from four hotels to 144; from 9,600 employees to 140,000; from annual revenue of $84 million to more than $4 billion.2 He could not stop, and Donna well knew it: “He could have just been out there fooling around with his cars or his boats, and say, ‘Well, I’ve got enough money. I don’t need to make any more.’ But he’s just not that kind of person.”

What Bill had not entirely expected was his brother Dick’s decision to resign from daily work at the company. Shortly after their father’s burial, feeling that the chains of filial obligation had diminished, Dick met with Bill. “I am not interested in running the restaurants anymore,” he said. “I did it because Dad wanted me to. You’re CEO; I don’t ever want to be CEO. I love you, and I support you. I will help you in any way I can, but I don’t want to be tied down to a desk here anymore.”

With that, Dick stepped back. No formal resignation was ever tendered or accepted. Dick spent fewer hours at headquarters and company events, but he had never spent as many hours as Bill had anyway, so there was little change there. He remained on the Marriott board of directors and was promoted to vice chairman, but he had no regular assignment other than to attend meetings and advise Bill. Thus, on the day of J.W.’s funeral, the Marriott family’s generational legacy with the company, so key to its corporate culture and success, had gone from three to one. The future rested primarily on Bill’s shoulders.

Bill never begrudged Dick his decision. He knew that sibling rivalry had torn many small and large family companies apart, and Dick had never challenged him. Instead, in the past and future, Dick unstintingly believed in and praised Bill’s leadership. “He’s been very loyal to me,” Bill said. “There’s never been a bit of conflict between us. He’s just as loyal and wonderful a brother as you can possibly ever have.”

The day after the funeral, a Sunday, Bill’s course seemed set. Only then could he begin to deeply consider the loss. After church meetings that day, Allie called her sons and asked them if they would come over and give her a priesthood blessing to help her find peace. Seated in a chair, Allie asked Bill to be “voice,” meaning that it was his responsibility to seek inspiration for the words of comfort and blessing that God would have him say. Such a blessing always begins with the recipient’s full name. As they all closed their eyes in prayer, Dick and Bill put their hands on Allie’s head. “Alice Sheets Marriott . . .” Bill began, almost in a whisper. And then he began to weep.

Many of the Marriotts returned to Lake Winnipesaukee during the week after the funeral. Their guests included John’s future wife, Angela Cooper, and Elder Boyd K. Packer, who was staying to dedicate the new Latter-day Saint chapel in Wolfeboro on Sunday, August 25. On Saturday morning Bill got up early to prepare his speedboat to give Elder Packer a tour of the lake; the fifteen-year-old Donzi was sometimes temperamental. The sky was clear, and the weather was already getting humid, but Bill was chilled and had his woolen sweater on. What was most different about that morning was the still air.

Bill began filling one of the boat’s tanks with gas about nine-thirty a.m. The family compound was just stirring. Elder Packer was finishing breakfast in Allie’s home. Ron and Debbie were at their home getting their five-year-old twins ready for the boat ride. David was still asleep in his parents’ house. John was telling his mother about another migraine headache that was plaguing him. His girlfriend Angie was taking a shower in a guest bedroom. In another guest room were Roger and Kathy Maxwell. Roger was the golf pro at Camelback Inn and had become quite close with J.W. and Allie during their months-long annual stays in Arizona.

Maxwell wandered out of the house onto the lawn. He was less than a hundred feet from the boathouse, where he could make out the shape of Bill pumping gas. At the controls of the boat, Bill was unaware that, in the still air, gas fumes were accumulating on the deck around his legs. Nor could he have known that the ignition switch would prove faulty and nearly fatal.

About 9:40 a.m., intending to check the gas gauge needle, Bill turned the ignition key. Suddenly there was an explosion that shook the windows and frames of all the nearby homes. Maxwell saw a fireball immediately engulf Bill, and he assumed it was the end of his boss. Incredibly, inside the boat, Bill was still conscious, staring at his pants and hands on fire. Instead of succumbing to immediate shock, he heard a loud voice: “Get out of the boat.” Still aflame, he managed to jump off the back of the boat into the cold water. He made his way around the back of the boathouse to the beach.

When John heard the explosion, he knew exactly what it was. He raced out the door past Maxwell, who was still frozen in place. Angie heard the explosion from the shower. She threw on some clothes, ripped the sheets off the bed, soaked them in water from the shower, and ran to the beach where John was helping Bill crawl onto the shore.

Angie was incredibly calm as she tended to Bill. “I know you don’t know me that well, but we’re going to have to take your clothes off,” she told him in a steady voice. As he groaned from the pain, she pulled off the heavy, wet V-neck wool sweater that had protected his torso but now threatened to do more damage, as it still retained enormous heat. Some of his hair and all of his eyebrows and eyelashes had been burned off. His polyester golf pants had mostly burned off, leaving only a few ragged remnants around his belt.

In what would be significant for Bill and his family, his knee-length garments, special underclothing worn by temple-attending Latter-day Saints and considered sacred, had not been singed or burned, fully protecting his upper legs in a miraculous manner. While his lower legs were badly burned, Angie could see that his hands had suffered the worst, having turned white and bloodless, with skin hanging off them like inverted gloves. She carefully wrapped his burned flesh in cold, wet sheets and towels. Angie and Donna helped Bill into the family station wagon, which could make it to Huggins Hospital in Wolfeboro faster than the ambulance could make the round-trip.

The Marriott fire was the largest blaze ever seen on the shores of Lake Winnipesaukee to anyone’s memory. The firefighters faced a raging inferno fueled by gas, wood, and plastic, not only at Bill’s boathouse but also at the neighbor’s—a classic $500,000 boathouse from the 1920s that went up in flames. The fire increased as secondary explosions went off. Boating sightseers came from far and near to watch the blaze. Bill’s boathouse was a smoking ruin. The Donzi and the yellow speedboat moored with it both burned down to the waterline and sank. The total damage was estimated at nearly $1 million.

At the small hospital, the doctors and nurses knew they were not up to the task ahead. A helicopter was called to take Bill to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. While they waited, Elder Packer and Dick gave him a priesthood blessing. In it, Packer remarkably promised there would be no long-term repercussions, not even scarring on Bill’s face. The recovery would not be easy, but this tragedy had occurred “for a wise (divine) purpose.”

Before the helicopter arrived, the Huggins Hospital medical team made a serious mistake. Bill had lost a lot of fluids by the time he got to hospital, and nurses had correctly started him on IVs to bring up those levels. But, in their haste, they hadn’t warmed the bags. When the medics from Boston arrived, Bill’s temperature had dropped to 89 degrees and he was in danger of dying from hypothermia.

After the helicopter took off, Donna returned to the lake house with Allie and Elder Packer. He would remain at the lake for the chapel dedication on Sunday.

Bill was fortunate that Mass General’s burn unit was run by Dr. John F. Burke, who assigned himself to Bill’s case. Burke had an international reputation for a series of innovations in the treatment of burn victims. His most stellar achievement was to co-invent the world’s first viable artificial skin—an amalgam of shark cartilage, cow tissue, and plastic—which is known today as Integra and has saved the lives of countless burn victims since its creation in 1981.3

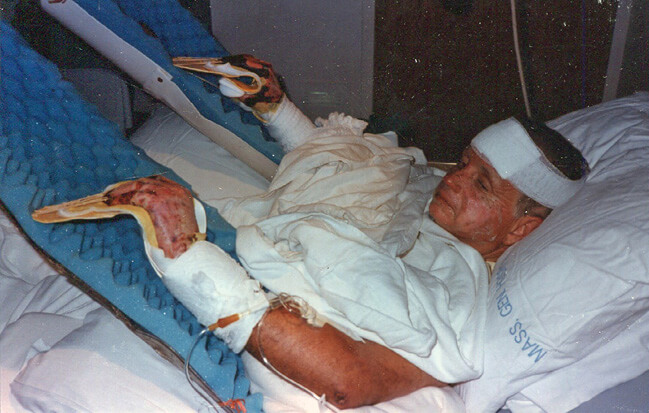

Within minutes of Bill’s arrival at Mass General, Dr. Burke ordered a series of life-preserving procedures for him. A thorough examination of Bill’s lungs determined that, miraculously, they were not damaged. Next, Bill was tethered to at least two IVs, one of them pumping liters of a saline solution into his arm, and the other infusing him with a high-protein, high-calorie, high-carbohydrate liquid. The team washed Bill’s burns in a silver nitrate solution, which caused a black stain over his body, and then treated the burns with Silvadene cream. Then Bill was wrapped almost completely in gauze bandages, leaving only his eyes, nose, and mouth uncovered. By the time Donna and Debbie arrived at the hospital, Bill had undergone all these procedures. His appearance was alarming. Entirely wrapped in the bandages, he lay abnormally still, eyes filled with concern and body tethered to tubes. But he could still joke.

Debbie decided to preserve his new “mummy look” with a Polaroid picture, and she showed it to him. As Bill looked at it for a minute, he couldn’t help but think about what a horrendous year 1985 had been for his family. Then Debbie saw a faint and familiar twinkle come into her dad’s eyes. He spoke in a halting, raspy voice: “Hey, Donna. Let’s put this on our Christmas card this year with the caption: ‘1985 was a hell of a year for us. We hope next year is better for you!’”

Bill didn’t see the first public Marriott bulletins to news outlets. Spokesman Al Rankin understated the severity of the injuries; the company expected him to be released from the hospital “in a few days.” The only accurate part of the statement was that, “all things considered, he’s in good spirits.”4

The Marriott stock price had dipped only slightly when J.W. had died less than two weeks earlier, mainly because savvy investors knew that Bill had been running the company for two decades. But when news of Bill’s brush with death was reported, there was a more distinct downturn in price. The stock stabilized after a few days as Rankin kept reassuring nervous investors that Bill would soon be back to work.

Bill underwent isograft skin surgery by Dr. Burke, which meant grafting healthy tissue onto the wounds. Dr. Burke never used his own artificial skin creation unless the patient was so extensively burned that there was not enough of the patient’s own skin to graft. But the doctor did something unexpected to save Bill’s hands. “He used super glue to attach hooks—like those from a lady’s dress—to my fingernails,” Bill explained. “He then used ping pong paddles with dress hooks at the top. Then, he stretched my hands flat across the paddles and used rubber bands to attach the hooks on my fingers to the hooks on the paddles. . . . I had paddles for hands for over a week in the hospital.”5

The body of a burn victim contracts upon itself, and Dr. Burke’s invention saved Bill from having clawlike hands for the rest of his life. Hospitals now routinely use splints, skintight Jobst garments, and extensive physical therapy to stretch contracting limbs, but in the mid-1980s, what Burke did with the Ping-Pong paddles was ingenious.

During Bill’s sixteen-day stay at Mass General, Donna discouraged visitors except immediate family. After a few days, she let John and David visit. “It was overwhelming,” John recalled. “They tell you he’s doing okay, but it’s hard to separate that from what you’re seeing—your father looking like charred beefsteak.” His younger brother, David, vomited on seeing his dad’s condition. “The whole thing was just upsetting, and I ended up running into the bathroom of his room and throwing up all over the place.”

Bill’s painful recovery.

Dr. Burke dropped by often to check on Bill, and the two men quickly bonded. On Bill’s second day in the hospital, President Ronald Reagan called from the White House to check on him. Dr. Burke ribbed Bill about it. “What the hell is he calling you for?” Burke said. “Doesn’t the president have anything better to do than talking to you?”

At the hospital, Bill was taught a dissociative technique of pain management. The doctor asked him to think about the times when he felt most relaxed. Easy, Bill responded, when he was at the wheel of his boat on the lake, the sun overhead, and smooth water racing by him. He found that particular visualization an effective way to distance his mind from his pain-racked body.

A very low point at the hospital for Bill, which came after he had been there about a week, had nothing to do with his continuous pain. It was the day Dick called with bad news. Allie had had a serious accident. She was stepping off the back porch of the lake house to feed her golden retriever, Rusty, when she fell over the dog and broke her pelvis. Dick was going to drive her home to Washington, D.C., to recuperate. “Here I was laid up in Mass General for burns,” Bill recalled. “Dad had died the week before. Now Mom had broken her pelvis. At this point, Dick was the only one walking around.”

Stephen was visiting from Phoenix at that time and wrote in his journal: “Dad is all right. He is in a lot of pain. He has lost about 20 pounds and he’s very weak. He has also aged. However, the doctor said he is healing well.” Stephen found his dad remarkable, never complaining about the accident or the pain. He refused to break down. But it was from Bill’s deep well of empathy that, upon hearing the news of his mother’s accident, he finally wept for just a moment. Stephen recorded with admiration: “The only time I really saw Dad cry was while we were together in the hospital and he learned that Grandma Marriott fell and broke her pelvis. And then, he wasn’t crying for himself.”6

When Bill hit the two-week mark at Mass General, he had had enough. “I can’t really stand this anymore,” he confided to Donna. “The smell in this burn unit is so bad. People are moaning and groaning and crying out in pain. I’m not getting any sleep. I’ve got to go home.”

Donna approached Dr. Burke, and he consented to the release on two conditions: that Donna learn how to change the dressings, and that Bill return every week to Mass General for physical therapy and progress checks. Nurse Donna was a quick study, and Bill was released into her care on the sixteenth day. To play it safe, they drove to the lake house to try the new arrangement for a few days before venturing farther from the hospital.

Donna steeled herself for the pain she knew she inflicted on Bill every few hours when she changed the dressings. The process involved boiling saltwater first, and then using wet gauze on the old dressings so removing them would not pull off new skin. After applying cream, she redressed them—the hands, the two calves, and the graft site on his hip. (His face had been flash-burned—like a bad sunburn—and was mostly healed by the time he was discharged from the hospital.)

Bill and Donna had been home only a week when a setback occurred. Having been cooped up for so long, Bill was trying to do more things around the house than he should. On his way to the basement, he collapsed and fell down the stairs, dislocating his shoulder and ripping open at least one of his hand grafts. He shouted for help, and John rushed to his aid. John found his dad a few steps from the bottom of the stairs with his shoulder dangling, one hand bleeding, and appearing physically spent. John knew he couldn’t lift his father up the stairs alone in that condition, so, besides bandaging his hand, he would have to put the shoulder back in its socket.

A memory from seventh grade came to John’s mind. The family was at Camelback for the Christmas holidays, and Bill had driven John and Stephen to Flagstaff for some skiing. Since he didn’t ski, Bill was walking up the side of the slope to watch his sons, when he slipped on an icy patch and dislocated a shoulder. John and a member of the ski patrol skied to his side and popped the shoulder back into place.

Sitting on the stairs, John needed Bill to relax his muscles. He called to his mother to bring Valium. She brought one. “He needs three,” John said, and sent her back to the medicine cabinet. Then, when Bill was feeling no pain, John popped his shoulder back into place. After that, it took half an hour to boost Bill up the stairs. “John was there when I needed him,” Bill recounted with emotion the following March at the wedding luncheon for Angie and John. “John was there and carried me to the top of the stairs, helped me get my shoulder back in place, and got me back to bed. That was a moment of closeness and tenderness that I will never forget.”

The fall had torn the graft on one of Bill’s fingers, so he and Donna flew to Boston the next day, where Dr. Burke grafted some of Bill’s skin that had been kept in the hospital freezer. After that incident, Bill tried not to overdo again. Donna rarely left Bill’s side during the four-plus months when he recuperated. She counseled him through the natural depression that afflicts burn victims. She traveled with him to Boston, where he repeatedly endured pain as the therapist bent his fingers again and again so they would retain full range of motion. She continued to change the bandages at the five sites, day after day, hundreds of times. “There were days when I didn’t know how I was going to get David to school and back because I was so tired from taking care of Bill,” she recalled. Occasionally, she accepted help from others for the grocery shopping and cooking, but not to change Bill’s bandages. The family could have afforded in-home nursing care, so why didn’t Donna opt for that? “I guess,” she said, “if you love somebody enough, you do what you can to take care of them. I just felt it was what I needed to do. Things like that make you closer.”

Stephen saw the recovery process up close and had his own thoughts. “I really have great parents,” he wrote during an October visit home. “Neither of them has complained this whole year despite the setbacks and trials. [Mom is] rarely to bed before 12:00 a.m., and she’s up early to help Dad. She’s tired, exhausted even, but she doesn’t complain. My love and respect has increased greatly for my parents. They are valiant.”

Except for attending the grand opening of the New York Marriott Marquis in October 1985, Bill did not return to work full-time until the following January. He waited until he could fully dress himself and tie his own shoes. That month, he left on his first long-distance business trip to California. Donna was suffering from a bad cold as they said good-bye.

By the next night, when Bill called her from the West Coast, Donna couldn’t talk; she could barely breathe. He hung up and called the family doctor, who rushed over to see her. After a quick examination, he was alarmed. “Find somebody to take care of David,” the doctor ordered. “I’m taking you to the hospital now.”

In Donna’s view, she had been so worn out from the four months of care and stress that her body finally crashed with a potentially fatal disease. The diagnosis was bacterial epiglottitis, a disease in which bacteria infects and swells the epiglottis to the point that every time the afflicted person swallows, the air passage closes and he or she can’t breathe. Donna was hooked up to IVs of steroids and antibiotics to reduce the swelling. Bill took the next available flight home and went straight to the hospital when he landed. It was his turn to be the caretaker.

After three or four days, when she was on the mend, Donna checked herself out of the hospital. Epiglottitis might have been the illness that killed George Washington, but it was not going to take down Donna Garff Marriott—not if she had anything to say about it. And she did.

Bill and Donna left the hospital hand in hand, both resolute and optimistic that, despite its rough beginning, 1986 was going to be a better year for them.