Chapter 23

Donna constantly feared that her husband would break under the pressure of the company’s financial crisis. He was exercising regularly, but his blood pressure was rising and his stress level, in her view, was off the charts. The memory of J.W.’s strong opinions shook Bill’s confidence and caused him to second-guess every major decision. “Again and again, my husband would raise the question at home: ‘What would my father think of me?’” Donna recalled.

No one had been tougher on Bill than his father about avoiding debt. General Counsel Sterling Colton witnessed it up close at board meetings. “Every board meeting [J.W.] delivered a lecture on the evils of debt. I can still hear him. It was every meeting where he was very critical of Bill in front of the board members. Bill would take it, but it was hard on him. Then, five years after his father was gone and we started to go under, both Bill and I could hear his father say: ‘I told you so!’”

As forcefully as she could, Donna urged Bill to get help for his stress, and he learned some coping skills from Dr. Stephen Hersh, a clinical professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, who became a close family friend.

But the best medicine for Bill was getting the company on a more even keel because of the $400-million credit line. As it turned out, Marriott never had to draw on it. Buyers were found for the Marriott-owned Big Boy and Howard Johnson’s restaurants. Marriott’s employee profit-sharing trust showed solidarity by buying five Courtyards. CFO Bill Shaw sold $62 million of the time-share division’s “receivables.” And, through Shaw’s patient work, the Tokyo-based Nomura group finally came through with a helpful mortgage for the San Francisco Marriott, which better positioned it for its subsequent sale.

Despite the positive gains, the company still had a long way to go. During this time of financial struggle, the negative press continued to weigh heavily on Bill. The worst of it was the April 1991 cover story in Regardie’s, a Washington business magazine named after its mercurial founder, Bill Regardie. Writer Keith Girard drove home the idea that Bill was past his prime: “Today, at 57, he’s a lion in winter; his health is questionable and his management talent is suspect. Which raises a nagging question: Does the chairman have the strength to rise again?” The cover featured an unflattering photo of Bill with the headline, “What the Hell Happened to Marriott?”1

The article received little notice outside D.C. because, by the time it was published, the information was stale. To meet the April publication deadline, Girard had to finish the final draft in early January, weeks before the $400-million credit line had turned the perception of the company around. A few months later, Bill ran into Regardie himself and buttonholed him. At the time, the magazine’s advertising revenue was dropping. Still stinging from the article, Bill warned the publisher: “When you go out of business, I am going to run a full-page ad in the Washington Post with your picture on it and it’s going to say, ‘What the Hell Happened to Regardie’s?’” The magazine folded at the end of the following year. Bill never bought that ad, but decades later he summarized the episode with evident pride: “Regardie’s took that awful picture of me and put it on the cover, and I’m still going strong while Regardie’s went broke.”

In spite of the company’s crisis, Bill’s stature in the business community was substantial. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce had asked him to be their chairman a few years before, which he had declined because of his busy schedule. That recognition from the business community meant that when Bill called for a jump start to the economy a week after the launch of the ground war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq (Operation Desert Storm), important business and political leaders listened. He issued a clarion call for an aggressive response to the crisis at a 1991 dinner meeting of President George H. W. Bush’s Business Roundtable:

“As we [corporations] stay home and ignore calling on our customers or attending meetings or seeing our people, trade is languishing, unemployment is rising, and sales are dropping,” Bill said. “The domino effect is cascading throughout our consumer ranks and could throw us into the worst recession of our lives. Presidents of airlines tell me that if this continues, all the world’s airlines will be bankrupt in six months. For those who have restricted travel, I urge reconsideration. If our economy falls apart because of this war, Saddam will have won a major victory in spite of his certain defeat on the battlefield.”2

Among the first to step up to the challenge was First Lady Barbara Bush, who flew on a commercial plane on Valentine’s Day from D.C. to Indianapolis for a veterans’ hospital visit. “People basically were afraid to travel because they thought Iraqi terrorists would blow up the airplanes,” Bill recalled. “So we got Barbara Bush to take that flight to prove to the American public that it was safe to fly. She commented to me, ‘Isn’t it the silliest thing you’ve ever heard? That if I fly on an airplane it proves they are all safe?’ But she was willing to do it, and it really helped.”

Bill followed up by forging a coalition of fifty travel-industry competitors that put up $6 million for a six-week national advertising campaign. “We’re going to be telling people that you can’t remember those wonderful vacations if you don’t take them,” Bill said. “And we’re going to tell business people you can’t do business by fax machine. They’ve got to get out and press the flesh.”3

Meanwhile, Marriott had been supportive of the war effort in various ways. Many of the hotels and restaurants offered free breakfasts for military families, put together care packages for the soldiers serving abroad, and hosted frequent blood drives. President Bush personally praised the corporation’s efforts, especially when the Cairo Marriott became his “Cairo White House” during a visit to forge a broad military coalition.4

America was in an ebullient mood when the Gulf War ended, and Marriott was a significant part of that celebration. The JW Marriott Hotel in D.C. became the headquarters for the national festivities culminating in the June 8, 1991, victory parade, and the company made a substantial donation to the cost of the parade. In addition, area Marriott hotels gave free rooms to visiting family members of the 373 American troops killed in the conflict.

Still flush from that feeling of victory, Bill and Donna moved into a new home two weeks later. They had lived in the same modest four-bedroom, two-story colonial house in the Kenwood subdivision for thirty-five years. Despite the Marriotts’ increasing wealth over the years, there were several reasons why they did not trade up to a bigger home. One was that Bill never wanted his children to think they were “big shots.” Explained daughter Debbie: “My father never made us feel like we had any money or that we were more special or more wealthy than anybody else. The house we lived in was the best way to underline that.”

A second reason he stayed was that, as a Church leader, he knew a mansion might intimidate those whom he counseled on spiritual and secular matters, especially members who experienced personal financial difficulties.

A third reason was that he knew his father would give him grief if he bought a bigger house. J.W. had always thought even the Kenwood home was too much. “His dad was furious with Bill when we bought the home in Kenwood in 1956,” Donna recalled. “He wanted us to go into a small starter house.”

Bill didn’t seriously consider buying or building a new home until after his father died in 1985. When he helped his mother clean out his father’s closets, a new resolve began to grow, which he relayed to Debbie: “Grandpa worked so hard and he had so much money, but he hadn’t bought a new suit in ten years. He had a few nice watches that people gave him, and lots of cowboy boots, but that was it. The air conditioning doesn’t work in his house, the plumbing is crummy, and the plaster is falling off the walls. I don’t want to be like that. While I don’t want to be materialistic, I want to enjoy what I’ve worked for. It’s time to have a nice new house.”

A year and a half after J.W. died, Bill and Donna paid $500,000 for a lot in Potomac, Maryland, overlooking a wooded ravine and the Avenel Golf Course (where the Kemper Open professional golf tournament was then played). Bill was intimately involved in every aspect of the Georgian-style brick home construction. Over the next four years, Bill and Donna spent $8.7 million on the home’s design, construction, furnishings, and art. The most unusual feature was a detached garage for Bill’s private museum of classic cars. The $2.8-million sale of his 1956 Ferrari 410 Sport, which he had bought for $275,000 a few years before, helped pay for the house.

On June 26, 1991, Bill, Donna, and David moved into their new 15,000-square-foot home. Two months later, their Kenwood house sold for $862,500 to the country of Sweden, which used it as a diplomatic residence. That was an $800,000 profit from Bill’s original purchase price, but he couldn’t help regretting the sale of Marriott stock to buy it in the first place. Those shares would have been worth roughly $25 million when the house sold. Laughing ruefully, Bill allowed, “I made a bad deal.”

By the end of 1991, Marriott had become a different company. Necessity required Bill to move away from hotel development to acquisition of troubled hotels. “Tough times provide many good opportunities for strong companies,” he advised senior executives at the beginning of the crisis. “There are many undervalued hotels for sale and we need to look out for them.” At least half a dozen hotels were acquired. In each case, sales improved significantly under the Marriott brand. Bill also focused on taking over management contracts from competitors, a process called “flag changing.” At least sixteen properties kept their owners but changed their flags to Marriott during the crisis.

While he was buying struggling hotels, Bill made serious headway in reducing the company’s debt by selling properties, too. The most reluctant sale for Bill was the 170-room Prince Charles de Gaulle Hotel in Paris. To get Sheraton to buy five other Marriotts, Bill had to throw in his Paris crown jewel. It would be five years before a Marriott hotel again opened for business in Paris.

Despite Marriott’s having cut its multibillion-dollar debt by half, the weight of the remainder was still a drag. In a speech at George Washington University, Bill declared that the Marriott mantra of 20 percent annual growth was history. “The quest for growth in EPS [Earnings per Share] had been my goal for the twenty-seven years I have been president. We had only one recession year [1975] when we did not increase EPS. Otherwise, our annual growth averaged 20 percent. We thought it could go on forever. But no tree grows to the sky. We knew we had to change our way of operating.”5

The change agent came in the person of Steve Bollenbach. Since Bollenbach had resigned as treasurer of Marriott in 1986, he had turned around the fortunes of two major hotel companies. Bill knew Bollenbach would return to Marriott only for the CFO slot, so he offered Shaw a promotion to open up the job. Shaw would replace Butch Cash as president of the Services Group. Cash had been a positive performer at the company for years before overreaching ambition had led him into the destructive “Twin Towers” competition. It was time for him to go. Cash subsequently became CEO of the Red Roof Inn chain.

With the stage set for further corporate evolution at the beginning of 1992, Bill was happy to have weathered the storms of 1990 and 1991. In moments of private and public reflection, he acknowledged with humble gratitude the blessings God had showered upon him and his family during that time. “The only way you can keep your sanity in trying times is to know that you have a family who supports you and sustains you and a church that is a bedrock foundation,” he said.

The second coming of Steve Bollenbach to the Marriott corporation was not seen as the arrival of a savior. Nevertheless, it was he who devised the idea that would change the company forever, and for the better.

His résumé included a stint as CFO of the struggling Holiday Corp. The first day he reported to work there, he discovered that Donald Trump “had decided to take over the company and fire all of the management because he felt they were a bunch of idiots,” Bollenbach recalled.6 He fended off the takeover by adding so many loans to the Holiday Corp.’s debt that it was no longer a tempting target for Trump.

To float the sinking Holiday Inn ship, he sold the majority of the company to Bass PLC, the British brewing giant, for $2.2 billion. He spun off the rest of the company—the lucrative casino hotels under the Harrah’s name, and its newer hotel brands, Embassy Suites, Hampton Inn, and Homewood Suites—into a new company named Promus.

Considering that Bollenbach was once a business adversary, it was more than a little ironic that in 1990 the nearly bankrupt Donald Trump was forced by his creditors to beg Bollenbach to come to work for him and rescue the Trump organization. Always up for a new challenge, Bollenbach agreed. Over the next two years, through debt-for-equity swaps and the sale of Trump’s flagging real-estate and casino assets, Bollenbach saved the future U.S. president from bankruptcy.7

Bill Shaw, who had kept in close touch with Bollenbach over the years, asked him if he would leave Trump for Marriott, and he did.

Bollenbach reported to work on March 2, 1992, and was surprised with changes that the financial crisis had wrought upon the once-thriving company he had left six years before. “It was the most demoralized place you can imagine; it was like a morgue. People were going around moaning, ‘We’re broke!’” But in Bollenbach’s eyes, they were overreacting, probably because of the stagnant value of their own stock options. Sure, the stock was on life support, but Bollenbach felt that the company had begun a significant turnaround, and the problems were fixable. In retrospect, he observed that his optimism may have come from the lifesaving mission he had completed at his last job. “I’d been working on Donald Trump’s problems and knew what real financial problems were about.”

A month into the job, Bollenbach gave Bill a list of objectives. In hindsight, the most important item was #7: “Revise Marriott story.”

“We had a short-term story, which was that we had to sell the real estate that was holding back our earnings,” Bill explained. “We were besieged by calls from security analysts who only wanted to know if we had sold any real estate that day. We said, ‘Hey, we have more to tell than that,’ but they wouldn’t listen. Steve felt we were focusing too much on the sale of real estate, and he wanted to get us off that. I agreed.”

Bollenbach suggested that the new story should be, “It’s really a good time to own these hotels because they’re good hotels.” Marriott was not going to get rid of any of its premium properties at fire-sale prices, no matter how depressed the market got. In the meantime, Bollenbach needed to extend the maturity of Marriott’s various loans, so he quickly moved ahead with Bill Shaw’s plan to sell bonds. The first $200-million lot was for twenty-year bonds, and the second $200-million sale was for ten-year bonds. Bond sales include a large document called an “indenture,” which is full of restrictions on the company selling the bonds. The fewer restrictions, the higher the interest rate offered. For these bonds, Marriott offered higher interest because the indenture was less restrictive.

Bollenbach expected that he would have to put on the usual road shows before the sales, which were traveling presentations to potential investors in New York City and elsewhere. “But the bond market had gotten very hot, particularly for Marriott bonds,” Bollenbach discovered as he began calling investment bankers to broker the sales. One told him to forget the dog-and-pony shows and just let his bank sell each lot over the phone. He agreed, and on April 22 and 29, $400 million of Marriott bonds sold in less than forty-five minutes over the phone on each day.

Though the bond sales were an incredible success, they didn’t rate even a mention in the financial press. Marriott stock, at about $16 a share, remained stagnant. “The stock market was saying, ‘So what?’ There was no press and no uptick. It was just a big yawn,” Bollenbach recalled.8 So it was time to totally concentrate on the one line in his objectives memo that Bill had highlighted: “We will need to adopt a different approach to creating shareholder value.” It resonated with Bill because that was precisely his job as CEO—to enhance shareholder value.

Three days after the last bond sale, Bollenbach and his wife headed north for a weekend at their Connecticut home. That Saturday, May 2, Bollenbach mused over the core issue—the dual nature of Marriott’s business, which confused investors. Was it a real-estate company or a management-service company? Then he hit on The Big Idea: Split the company into those two parts. That would be his way to revise the Marriott story.

The plan he worked out that weekend was unique. Companies with divergent missions typically split up via leveraged buyouts, hostile takeovers, spin-offs, and sales of unwanted assets—like Marriott’s own sale of its airline catering division several years before. But no one had split a company in two without involving a third-party buyer. This time, there would be no sale; there would be no new owner, just two Marriott companies.

In Bollenbach’s shorthand notes that weekend, the old company, which he dubbed “RealCo,” would become a real-estate-only company (including the hotels Marriott owned) and would also retain all the debt associated with those assets. “NewCo,” the spin-off, would be a nearly debt-free entity focused entirely on management services of hotels, food services, and other operations. Bill could be CEO of NewCo, where he would be free to grow the management side. Bollenbach himself could well be CEO of the “weaker” sister, the debt-laden RealCo. He foresaw that once the real estate market turned around in a few years, RealCo would become one of America’s top five hotel-owning firms.

The connection between the two companies would be vital for the health of both, so Bollenbach’s plan outlined a series of administrative and other services they would share, including the same headquarters building. But the core staff of each would be separate, as would the boards of directors. He felt Bill should be chairman of the NewCo board and hoped younger brother Dick would agree to be chairman of RealCo. The split would be accomplished with a special two-for-one dividend to stockholders. For the shares they had in RealCo—which was the planned survivor of the old Marriott corporation—they would receive the same amount of shares in NewCo.

The plan was elegantly simple in principle, but extremely complex and formidable to achieve. Consent would be needed from many players, including the board of directors and then the shareholders. General Counsel Sterling Colton’s team would also have the monumental task of seeking approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Internal Revenue Service, all the partners in the limited partnerships, all the landlords of leased sites, and a whole array of others. It was mind-boggling for Bollenbach to conceive that all the obstacles he foresaw might be overcome, but he was determined to try.

His first concern was the recently sold bonds. Did the fine print forbid such a corporate split? When he returned to the office Monday morning, his first call was to Colton’s best expert on the subject, William Kafes, who told him that the bondholders had no protective covenant that would prevent a company split. Bollenbach had not come up with the idea until after the bond sale, so there had been no obligation to warn the bond buyers. Still, those who had bought bonds in a diversified company would not be happy to find their bonds attached to a debt-laden real-estate-only company.

Bill immediately saw the exciting prospects of such a split and was enthusiastic, but he confessed to Bollenbach that he didn’t understand how it would work legally or financially. He told Bollenbach to make sure the Marriott legal team was in the loop, and to meet individually with every board member before the issue came to a vote. The company had no obligation to bondholders other than to pay annual interest on time and pay the principal when it was due. But an active secondary market, in which the bonds could be resold, would be adversely affected by such a split. Having anticipated the bondholders’ resistance, Bollenbach pledged that as the plan evolved, more would be done to manage their concerns.

Bollenbach had to come up with a code name for the project to keep it from leaking. In a moment of admittedly “sick humor,” Treasurer Matt Hart suggested “Project Bhopal,” after a 1984 toxic chemical plant explosion in India. Hart was thinking about the reaction the bondholders would have, but Bollenbach was not amused.9 Someone else suggested “Chariot” because it rhymed with Marriott, and Bollenbach adopted it.

Marriott executives were divided into two teams to advocate for RealCo and NewCo, to make sure each company got its due. It soon became evident that the “fairness” issue to bondholders would require a major revision of the plan. RealCo needed another revenue stream beyond the debt-laden real estate. So NewCo team members moved Marriott’s toll-road businesses to the RealCo side. But RealCo team members said that wasn’t enough. They wanted Marriott’s Host airport terminal restaurants and gift shops, too. Reluctantly, the NewCo team agreed. At that point, RealCo received its final name, Host Marriott. NewCo was given the name Marriott International (MI).

The historic transformation of Marriott nearly fell apart when financial consultants hired by Marriott, the James D. Wolfensohn investment banking firm, concluded that the current plans would not produce two thriving companies. The solution was for MI to give Host a $600-million line of credit. Then the other shoe dropped. Board member Dr. Thomas Piper, a senior associate dean at Harvard Business School, had just finished editing a book on business ethics. He was concerned that the bondholders might view the Marriott split as somehow unethical. Piper solved his problem by resigning from the board on September 29.

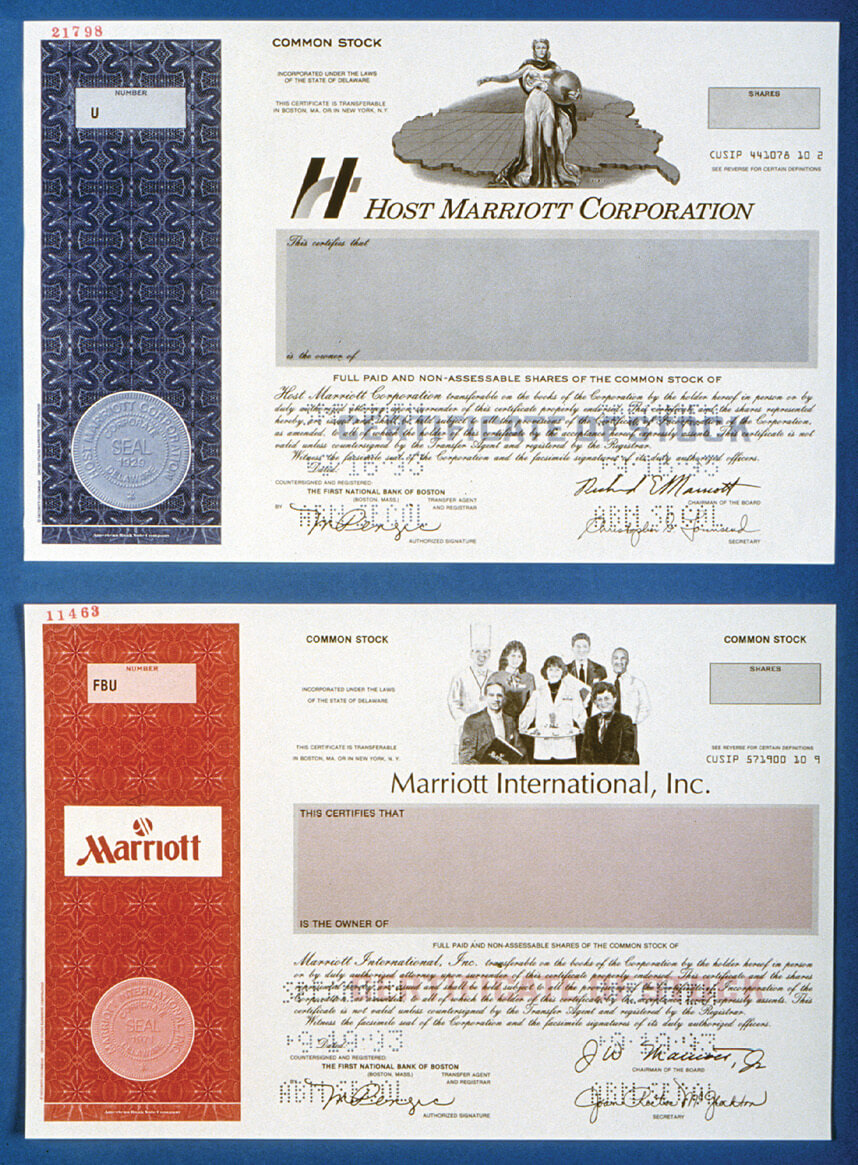

Stock certificates showing the split companies.

On October 4, the rest of the board voted unanimously in favor of the split. The following day, before an overflowing crowd of media and security analysts at the New York Marriott Marquis, Bill announced that, subject to shareholder approval the following year, the Marriott corporation would cease to exist; it would become two separate companies.

As expected, some bondholders expressed outrage, which dropped the bonds’ trading value by about 10 percent. Bill had been advised this would happen in the short term, but they would soon return to the par value. Meanwhile, the stock market was electrified. In an otherwise down day on the market, heavy trading in Marriott stock drove the share price up 12 percent, to $19.25. Bollenbach’s bold plan thus got the most positive first-day review from the only constituency to whom he had fiduciary responsibility.

The Washington Post neatly put the split in perspective: “That Marriott needed a radical pick-me-up is one of the few things about Project Chariot that people agree on. It represents, in effect, the blueprint for the third incarnation of one of the great Horatio Alger stories of the 20th century.”10

Bollenbach warned Bill time and again that once the split was announced, the bond traders would probably set the dogs loose on him. In the end, “It was worse than Bill expected,” Bollenbach observed. “In fact, it was even worse than I expected.”

The first hit occurred on the day of the announcement. Moody’s Investor Service immediately downgraded Marriott bonds from “investment grade” to what the industry refers to as “junk” status. Bond traders panicked and began selling. The value of the bonds in the resale market dropped from 110 percent of their original sale price the previous Friday to 80 percent on Monday. Marriott had plenty of money to pay the principal and interest promised to the original bond buyers. No one was going to get less than they had bargained for, if they bought and held those bonds to maturity. But for those who had purchased the Marriott bonds hoping to resell them for a profit in the secondary market, their bubble had burst in a big way that day.

The first two bondholder lawsuits against Marriott were filed in federal court in Baltimore a week after the announcement. This triggered a media pile-on like Bill had never known before or since. Some in the company began to jokingly refer to Project Chariot as “Chariot of Fire.” Newsday financial columnist Allan Sloan wasted no time launching an attack. “The folks at Marriott Corp. go out of their way to act classy,” he began. “The company’s chairman, J. Willard Marriott Jr., is a pillar of the business establishment. The company has nice hotels and a nice, upscale image. But this oh-so-classy operation is trying to pull off an incredibly tacky deal to enrich the Marriott family and other stockholders at the expense of Marriott bondholders. This is the kind of thing you expect from financial wheeler-dealers. It’s not the kind of fancy financial footwork you’re supposed to get from mainstream types like Bill Marriott.”11

In the financial media, terms such as opportunistic, predatory, slick, brazen, fiasco, and disaster were applied to the company’s plan and to Bill personally. He bore the attacks with outward equanimity. “The 61-year-old chief executive of Marriott Corp. has endured gale-force contempt,” the Washington Post observed. “Lawsuits against him and his Bethesda company have come whistling in like Scud missiles. One group of angry investors threatened to organize a boycott of the company’s hotels. The verbal abuse has been nearly constant. ‘Someone called me the scuzz of the earth last week,’ Marriott noted, though he seemed more bored than annoyed by the hostility.”12

The more savvy members of the financial press saw through the outrage to the nuts and bolts of the law. Marriott’s only obligation was to pay the principal and interest promised in the bond contract. If a bondholder had hoped to make more money by reselling the bonds at a profit, that was not Marriott’s responsibility. Marriott’s obligation to its stockholders was paramount and very different from bondholders. Shareholders expect to trade up, and it was Marriott’s job to run a healthy enough company that its shares continue to increase in value, but that isn’t stated in writing. With bondholders, the company has a legal contract, called an indenture, that guarantees annual interest payback. In the case of the Marriott bond sale, the indenture was less restrictive, meaning the company had more leeway, but the bond buyers also got better interest rates.

At the December 3 board meeting, Arne Sorenson, of the law firm Latham & Watkins, briefed the board on eight lawsuits filed against Marriott in Baltimore’s federal and circuit courts. He would represent Marriott in the suits and was confident about an eventual settlement. This marked the first appearance at Marriott of Sorenson, who was destined to become the company’s third CEO and its first non-Marriott-family chief. No one in that meeting could have predicted such an unlikely turn of events.

The majority of the bondholders were represented in court by Goldman Sachs. A smaller, more hostile group was led by PPM America Inc., a subsidiary of a large British insurance company. In March 1993, Marriott and the Goldman Sachs group reached a settlement in which Marriott offered to pay bondholders one percentage point more in interest on their bonds.

That left a bad taste as far as board member Harry Vincent was concerned. “The bondholders extorted money from the company by insisting that we buy them off, which we did,” he complained privately. The smaller PPM group refused to settle. Ironically, at the same time, the bonds in the secondary market had recovered in price nearly to their presplit level.

In July 1993, 85 percent of the stockholders voted in favor of the split as a “special dividend,” giving them one share of each company for every Marriott share they currently owned. The following October 8, after the IRS finally ruled the dividend would be tax-free, Marriott split into the two companies. The increased shareholder value exceeded all expectations. Just before the split had been announced the year before, Marriott stock was trading at $17.12½ a share. The combined price of the two new Marriott companies on opening day was $33.37½ per share—a remarkable 95 percent increase in the otherwise sluggish market.

Clearly, the markets had rewarded Marriott for its big surprise, but the PPM lawsuit alleging fraud remained. Some even suggested that there was a greater expectation of probity from the bondholders because Bill was a Latter-day Saint, and that hurt him personally. But the dark cloud had a silver lining, in Bill’s view, and that was his increasingly close association with the chief attorney for the defense, Arne (pronounced “Arnie”) Sorenson.

Two years after the first suit was filed, Judge Alexander Harvey began the jury trial in the U.S. District Court of Maryland in Baltimore on September 26, 1994. At the heart of the case was the bondholders’ accusation that Marriott had violated federal securities laws and defrauded the bondholders by failing to disclose the pending split of the company before the bonds were sold. The bondholders were claiming $18 million in actual losses and also asking punitive damages. To win, they had to prove that Marriott executives knew before the bond sales that they were going to separate the company.

Bill was called to the stand on October 4, the second week of the trial. In spite of the stress leading up to his testimony, he was cool and implacable. PPM’s attorney Larry Kill tried to imply that the split had been concocted by the Marriott family so they could enrich themselves. “That benefited you and your family, did it not?” Kill asked.

“It benefited all 65,000 shareholders,” Bill replied.

But, Kill said, the Marriott family alone had seen a $47-million gain in its stock in just one day—the day of the announcement. “I don’t know what it was,” Bill replied. “I never looked at it.”

It was this kind of attack that most upset Bollenbach. Months after the split was announced, he told Lodging magazine: “The thing I regretted about this transaction is when people made personal criticisms of Bill, because they didn’t have a way of understanding the man. . . . There was the criticism that this was some kind of financial maneuver to increase his wealth. This guy could care less about that. He started out following his father around to root beer stands and making hamburgers when he was nine years old and worked right through three heart attacks. This is his life. He’s not going to sell his stock. From Bill’s point of view, he’s not going to sell his stock for $5 or $50. What’s important to him is he’s got a company that can grow, that he can provide job opportunities for his people and he can deliver good services.”13

In his testimony, Bollenbach was equally dismissive when Kill asked him to defend the bonus Marriott paid him for devising and carrying out the split. He acknowledged that after the split he received a compensation package that included 1.5 million shares of stock to be doled out over five years. “It’s likely to be a lot of money,” Bollenbach said.

“About $6.4 million,” Kill said.

“I hope it will be more,” Bollenbach smiled, ruining Kill’s attempt to shame him.

When Bill came off the stand, the message he left with the jury was straightforward: He didn’t think about splitting the company until after the bond sale; he had no legal obligation to disclose the idea to bondholders or anyone else while it was a work in progress; and he had insisted the company do everything within its power to protect the bondholders and pay them back.

Even as he was harangued by Kill with charges of self-enrichment, Bill managed to slip something in that hurt PPM’s case. The jury was not supposed to know that most of the bondholders, including PPM itself, had already sold their bonds for a profit before the trial began, which undercut their claims for damages. Bill quickly let the jury know this before Kill could cut him off.

In his closing statement, Sorenson asked, “What is this case about? It’s about whether these large sophisticated institutional investors should be allowed to come into this court and get something they did not pay for.”

While the jury was deliberating, Bill unexpectedly had to fly to Salt Lake City with Donna to deliver a eulogy at the funeral of her father, Royal Garff. Donna’s sister Joanne and her husband, Ray Hart, joined him in the hotel room as Bill prepared his remarks, and they recalled how distracting the pending jury verdict was to him. He paced the room, fearing the impact the verdict would have on his company’s reputation and future. Bill said to Ray Hart, “Today, when this phone call comes, I may not have a Marriott hotel business. This thing may take us down.”

Hart decided to leave the hotel room at one point to walk to the nearby temple. Part of tradition in Latter-day Saint temples is to conduct group prayers for those needing consolation or help. Hart put Bill’s name on the daily prayer roll and returned to the hotel to tell him. “That’s the only thing I could think of that I could do to help you,” he told Bill. Within an hour, the phone rang.

After two years of legal wrangling, three weeks of trial, and fourteen hours of jury deliberation, the jurors sent a note to Judge Harvey. They were hopelessly deadlocked. Judge Harvey declared a mistrial.

Both sides asked the judge to decide the case himself rather than start a new trial. On January 25, 1995, Judge Harvey did just that. He dismissed the case against Marriott, saying the bondholders had not proved any of their claims. Rather than waste more money on legal fees, presuming PPM would try to appeal to a higher court, Marriott settled with PPM for a token $1.25 million on March 4, 1996.

One week after that final settlement, Arne Sorenson began his career at Marriott International. Bill had been so impressed with Sorenson that he had lobbied his trial lawyer for more than a year to work for the lodging company. Sorenson’s surprising rise at Marriott began with him spending a few months in the General Counsel’s office before moving to business development and then becoming CFO after only two years on the job. “He’s such a quick study and mastered a number of things that people take decades to do in a few short years,” Bill said. “I saw a bright future for him at Marriott.”14