Chapter 2

Writing a C# Program

Wrox.com Code Downloads for this Chapter

The wrox.com code downloads for this chapter are found at www.wrox.com/go/beginningvisualc#2015programming on the Download Code tab. The code is in the Chapter 2 download and individually named according to the names throughout the chapter.

Now that you’ve spent some time learning what C# is and how it fits into the .NET Framework, it’s time to get your hands dirty and write some code. You use Visual Studio 2015 (VS) throughout this book, so the first thing to do is have a look at some of the basics of this development environment.

Visual Studio is an enormous and complicated product, and it can be daunting to first-time users, but using it to create basic applications can be surprisingly simple. As you start to use Visual Studio in this chapter, you will see that you don’t need to know a huge amount about it to begin playing with C# code. Later in the book you’ll see some of the more complicated operations that Visual Studio can perform, but for now a basic working knowledge is all that is required.

After you’ve looked at the IDE, you put together two simple applications. You don’t need to worry too much about the code in these for now; you just want to prove that things work. By working through the application-creation procedures in these early examples, they will become second nature before too long.

You will learn how to create two basic types of applications in this chapter: a console application and a desktop application.

The first application you create is a simple console application. Console applications don’t use the graphical windows environment, so you won’t have to worry about buttons, menus, interaction with the mouse pointer, and so on. Instead, you run the application in a command prompt window and interact with it in a much simpler way.

The second application is a desktop application, which you create using Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF). The look and feel of a desktop application is very familiar to Windows users, and (surprisingly) the application doesn’t require much more effort to create. However, the syntax of the code required is more complicated, even though in many cases you don’t actually have to worry about details.

You use both types of application in Part III and Part IV of the book, with more emphasis on console applications at the beginning. The additional flexibility of desktop applications isn’t necessary when you are learning the C# language, while the simplicity of console applications enables you to concentrate on learning the syntax without worrying about the look and feel of the application.

The Visual Studio 2015 Development Environment

When Visual Studio is first loaded, it immediately presents you with the option to Sign in to Visual Studio using your Microsoft Account. By doing this, your Visual Studio settings are synced between devices so that you do not have to configure the IDE when using it on multiple workstations. If you do not have a Microsoft Account, follow the process for the creation of one and then use it to sign in. If you do not want to sign in, click the “Not now, maybe later” link, and continue the initial configuration of Visual Studio. At some point, it is recommended that you sign in and get a developer license.

If this is the first time you’ve run Visual Studio, you will be presented with a list of preferences intended for users who have experience with previous releases of this development environment. The choices you make here affect a number of things, such as the layout of windows, the way that console windows run, and so on. Therefore, choose Visual C# Development Settings from the drop-down; otherwise, you might find that things don’t quite work as described in this book. Note that the options available vary depending on the options you chose when installing Visual Studio, but as long as you chose to install C# this option will be available.

If this isn’t the first time that you’ve run Visual Studio, but you chose a different option the first time, don’t panic. To reset the settings to Visual C# Development settings, you simply have to import them. To do this, select Tools  Import and Export Settings, and choose the Reset All Settings option, shown in Figure 2.1.

Import and Export Settings, and choose the Reset All Settings option, shown in Figure 2.1.

Click Next, and indicate whether you want to save your existing settings before proceeding. If you have customized things, you might want to do this; otherwise, select No and click Next again. From the next dialog box, select Visual C#, shown in Figure 2.2. Again, the available options may vary.

Finally, click Finish, then Close to apply the settings.

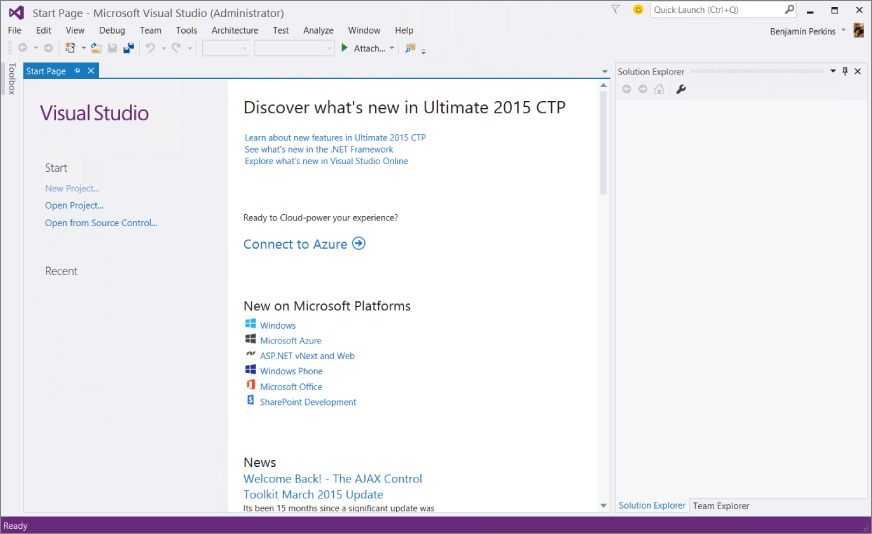

The Visual Studio environment layout is completely customizable, but the default is fine here. With C# Developer Settings selected, it is arranged as shown in Figure 2.3.

The main window, which contains a helpful Start Page by default when Visual Studio is started, is where all your code is displayed. This window can contain many documents, each indicated by a tab, so you can easily switch between several files by clicking their filenames. It also has other functions: It can display GUIs that you are designing for your projects, plain-text files, HTML, and various tools that are built into Visual Studio. You will come across all of these in the course of this book.

Above the main window are toolbars and the Visual Studio menu. Several different toolbars can be placed here, with functionality ranging from saving and loading files to building and running projects to debugging controls. Again, you are introduced to these as you need to use them.

Here are brief descriptions of each of the main features that you will use the most:

- The Toolbox window pops up when you click its tab. It provides access to, among other things, the user interface building blocks for desktop applications. Another tab, Server Explorer, can also appear here (selectable via the View

Server Explorer menu option) and includes various additional capabilities, such as Azure subscription details, providing access to data sources, server settings, services, and more.

Server Explorer menu option) and includes various additional capabilities, such as Azure subscription details, providing access to data sources, server settings, services, and more. - The Solution Explorer window displays information about the currently loaded solution. A solution, as you learned in the previous chapter, is Visual Studio terminology for one or more projects along with their configurations. The Solution Explorer window displays various views of the projects in a solution, such as what files they contain and what is contained in those files.

- The Team Explorer window displays information about the current Team Foundation Server or Team Foundation Service connection. This allows you access to source control, bug tracking, build automation, and other functionality. However, this is an advanced subject and is not covered in this book.

- Just below the Solution Explorer window you can display a Properties window, not shown in Figure 2.3 because it appears only when you are working on a project (you can also toggle its display using View

Properties Window). This window provides a more detailed view of the project’s contents, enabling you to perform additional configuration of individual elements. For example, you can use this window to change the appearance of a button in a desktop application.

Properties Window). This window provides a more detailed view of the project’s contents, enabling you to perform additional configuration of individual elements. For example, you can use this window to change the appearance of a button in a desktop application. - Also not shown in the screenshot is another extremely important window: the Error List window, which you can display using View

Error List. It shows errors, warnings, and other project-related information. The window updates continuously, although some information appears only when a project is compiled.

Error List. It shows errors, warnings, and other project-related information. The window updates continuously, although some information appears only when a project is compiled.

This might seem like a lot to take in, but it doesn’t take long to get comfortable. You start by building the first of your example projects, which involves many of the Visual Studio elements just described.

Console Applications

You use console applications regularly in this book, particularly at the beginning, so the following Try It Out provides a step-by-step guide to creating a simple one.

The Solution Explorer

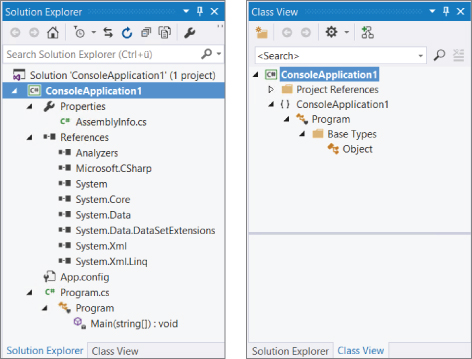

By default, the Solution Explorer window is docked in the top-right corner of the screen. As with other windows, you can move it wherever you like, or you can set it to auto-hide by clicking the pin icon. The Solution Explorer window shares space with another useful window called Class View, which you can display using View  Class View. Figure 2.7 shows both of these windows with all nodes expanded (you can toggle between them by clicking on the tabs at the bottom of the window when the window is docked).

Class View. Figure 2.7 shows both of these windows with all nodes expanded (you can toggle between them by clicking on the tabs at the bottom of the window when the window is docked).

This Solution Explorer view shows the files that make up the ConsoleApplication1Program.csAssemblyInfo.cs

NOTE

All C# code files have a .cs

You don’t have to worry about the AssemblyInfo.cs

You can use this window to change what code is displayed in the main window by double-clicking .cs

You can also expand code items such as Program.cs

The References

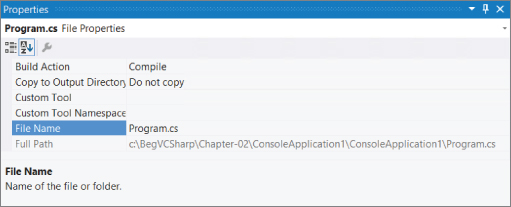

The Properties Window

The Properties window (select View  Properties Window if it isn’t already displayed) shows additional information about whatever you select in the window above it. For example, the view shown in Figure 2.8 is displayed when the

Properties Window if it isn’t already displayed) shows additional information about whatever you select in the window above it. For example, the view shown in Figure 2.8 is displayed when the Program.cs

Often, changes you make to entries in the Properties window affect your code directly, adding lines of code or changing what you have in your files. With some projects, you spend as much time manipulating things through this window as making manual code changes.

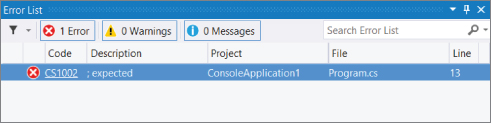

The Error List Window

Currently, the Error List window (View  Error List) isn’t showing anything interesting because there is nothing wrong with the application. However, this is a very useful window indeed. As a test, remove the semicolon from one of the lines of code you added in the previous section. After a moment, you should see a display like the one shown in Figure 2.9.

Error List) isn’t showing anything interesting because there is nothing wrong with the application. However, this is a very useful window indeed. As a test, remove the semicolon from one of the lines of code you added in the previous section. After a moment, you should see a display like the one shown in Figure 2.9.

In addition, the project will no longer compile.

NOTE

In Chapter 3, when you start looking at C# syntax, you will learn that semicolons are expected throughout your code — at the end of most lines, in fact.

This window helps you eradicate bugs in your code because it keeps track of what you have to do to compile projects. If you double-click the error shown here, the cursor jumps to the position of the error in your source code (the source file containing the error will be opened if it isn’t already open), so you can fix it quickly. Red wavy lines appear at the positions of errors in the code, so you can quickly scan the source code to see where problems lie.

The error location is specified as a line number. By default, line numbers aren’t displayed in the Visual Studio text editor, but that is something well worth turning on. To do so, tick the Line numbers check box in the Options dialog box (selected via the Tools  Options menu item). It appears in the Text Editor

Options menu item). It appears in the Text Editor All Languages

All Languages  General category.

General category.

You can also change this setting on a per-language basis through the language-specific settings pages in the dialog box. Many other useful options can be found through this dialog box, and you will use several of them later in this book.

Desktop Applications

It is often easier to demonstrate code by running it as part of a desktop application than through a console window or via a command prompt. You can do this using user interface building blocks to piece together a user interface.

The following Try It Out shows just the basics of doing this, and you’ll see how to get a desktop application up and running without a lot of details about what the application is actually doing. You’ll use WPF here, which is Microsoft’s recommended technology for creating desktop applications. Later, you take a detailed look at desktop applications and learn much more about what WPF is and what it’s capable of.

TRY IT OUT

Creating a Simple Windows Application: WpfApplication1\MainWindow.xaml and WpfApplication1\MainWindow.xaml.cs

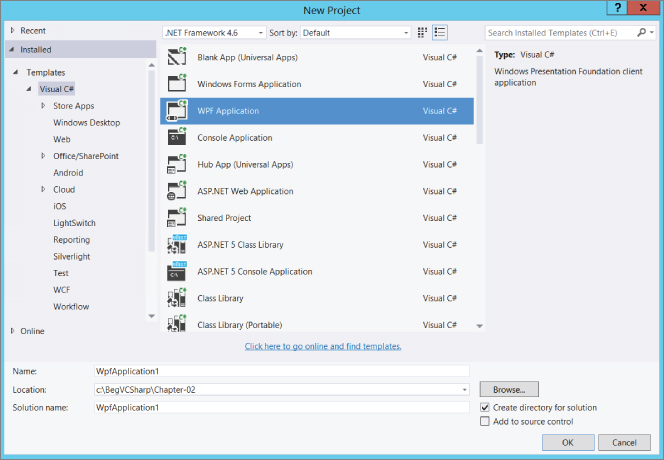

- Create a new project of type WPF Application in the same location as before (

C:\BegVCSharp\Chapter02WpfApplication1

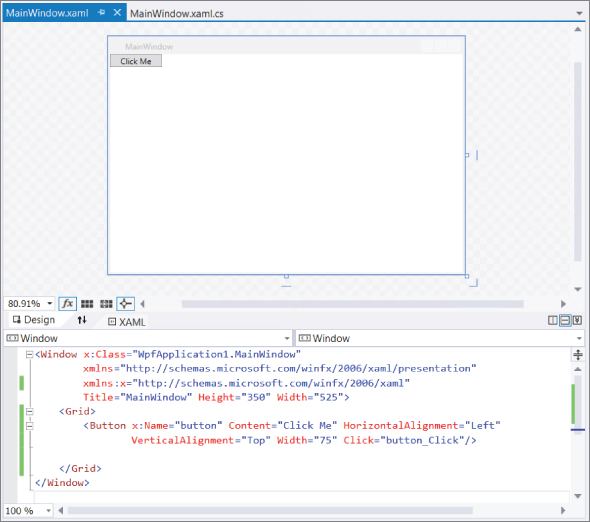

- Click OK to create the project. You should see a new tab that’s split into two panes. The top pane shows an empty window called MainWindow and the bottom pane shows some text. This text is actually the code that is used to generate the window, and you’ll see it change as you modify the UI.

- Click the Toolbox tab on the top left of the screen, then double-click the Button entry in the Common WPF Controls section to add a button to the window.

- Double-click the button that has been added to the window.

- The C# code in

MainWindow.xaml.csprivate void button_Click(object sender, RoutedEvetnArgs e) { MessageBox.Show("The first desktop app in the book!"); } - Run the application.

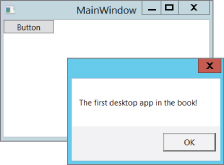

- Click the button presented to open a message dialog box, as shown in Figure 2.11.

- Click OK, and then exit the application by clicking the X in the top-right corner, as is standard for desktop applications.

How It Works

Again, it is plain that the IDE has done a lot of work for you and made it simple to create a functional desktop application with little effort. The application you created behaves just like other windows — you can move it around, resize it, minimize it, and so on. You don’t have to write the code to do that — it just works. The same is true for the button you added. Simply by double-clicking it, the IDE knew that you wanted to write code to execute when a user clicked the button in the running application. All you had to do was provide that code, getting full button-clicking functionality for free.

Of course, desktop applications aren’t limited to plain windows with buttons. Look at the Toolbox window where you found the Button option and you’ll see a whole host of user interface building blocks (known as controls), some of which might be familiar. You will use most of these at some point in the book, and you’ll find that they are all easy to use and save you a lot of time and effort.

The code for your application, in MainWindow.xaml.csMainWindow.xaml

This code is written in XAML, which is the language used to define user interfaces in WPF applications.

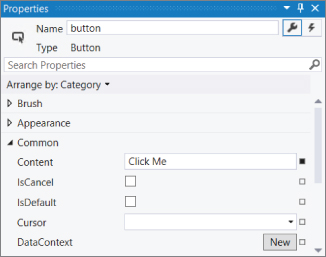

Now take a closer look at the button you added to the window. In the top pane of MainWindow.xamlContentButtonClick Me

The text written on the button in the designer should also reflect this change, as should the XAML code, as shown in Figure 2.13.

There are many properties for this button, ranging from simple formatting of the color and size to more obscure settings such as data binding, which enables you to establish links to data. As briefly mentioned in the previous example, changing properties often results in direct changes to code, and this is no exception, as you saw with the XAML code change. However, if you switch back to the code view of MainWindow.xaml.cs

NOTE

NOTE that it is also possible to use Windows Forms to create desktop applications. WPF is a newer technology that is intended to replace Windows Forms and provides a far more flexible and powerful way to create desktop applications, which is why this book doesn’t cover Windows Forms.

What You Learned in This Chapter

What You Learned in This Chapter

| Topic | Key Concepts |

| Visual Studio 2015 settings | This book requires the C# development settings option, which you choose when you first run Visual Studio or by resetting the settings. |

| Console applications | Console applications are simple command-line applications, used in much of this book to illustrate techniques. Create a new console application with the Console Application template that you see when you create a new project in Visual Studio. To run a project in debug mode, use the Debug  Start Debugging menu item, or press F5. Start Debugging menu item, or press F5. |

| IDE windows | The project contents are shown in the Solution Explorer window. The properties of the selected item are shown in the Properties window. Errors are shown in the Error List window. |

| Desktop applications | Desktop applications are applications that have the look and feel of standard Windows applications, including the familiar icons to maximize, minimize, and close an application. They are created with the WPF Application template in the New Project dialog box. |