And I will lay sinews upon you, and will bring up flesh upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and ye shall live.—Ezekiel 37:6

Not since the Lord himself showed his stuff to Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones had anyone brought such grace and skill to the reconstruction of animals from disarticulated skeletons. Charles R. Knight, most celebrated of artists in the reanimation of fossils, painted all the canonical figures of dinosaurs that fire our fear and imagination to this day. In February 1942, Knight designed a chronological series of panoramas, depicting the history of life from the advent of multicellular animals to the triumph of Homo sapiens, for the National Geographic. (This is the one issue that’s always saved and therefore always missing when you see a “complete” run of the magazine on sale for two bits an issue on the back shelves of the general store in Bucolia, Maine.) He based his first painting in the series—shown on the jacket of this book—on the animals of the Burgess Shale.

Without hesitation or ambiguity, and fully mindful of such paleontological wonders as large dinosaurs and African ape-men, I state that the invertebrates of the Burgess Shale, found high in the Canadian Rockies in Yoho National Park, on the eastern border of British Columbia, are the world’s most important animal fossils. Modern multicellular animals make their first uncontested appearance in the fossil record some 570 million years ago—and with a bang, not a protracted crescendo. This “Cambrian explosion” marks the advent (at least into direct evidence) of virtually all major groups of modern animals—and all within the minuscule span, geologically speaking, of a few million years. The Burgess Shale represents a period just after this explosion, a time when the full range of its products inhabited our seas. These Canadian fossils are precious because they preserve in exquisite detail, down to the last filament of a trilobite’s gill, or the components of a last meal in a worm’s gut, the soft anatomy of organisms. Our fossil record is almost exclusively the story of hard parts. But most animals have none, and those that do often reveal very little about their anatomies in their outer coverings (what could you infer about a clam from its shell alone?). Hence, the rare soft-bodied faunas of the fossil record are precious windows into the true range and diversity of ancient life. The Burgess Shale is our only extensive, well-documented window upon that most crucial event in the history of animal life, the first flowering of the Cambrian explosion.

The story of the Burgess Shale is also fascinating in human terms. The fauna was discovered in 1909 by America’s greatest paleontologist and scientific administrator, Charles Doolittle Walcott, secretary (their name for boss) of the Smithsonian Institution. Walcott proceeded to misinterpret these fossils in a comprehensive and thoroughly consistent manner arising directly from his conventional view of life: In short, he shoehorned every last Burgess animal into a modern group, viewing the fauna collectively as a set of primitive or ancestral versions of later, improved forms. Walcott’s work was not consistently challenged for more than fifty years. In 1971, Professor Harry Whittington of Cambridge University published the first monograph in a comprehensive reexamination that began with Walcott’s assumptions and ended with a radical interpretation not only for the Burgess Shale, but (by implication) for the entire history of life, including our own evolution.

This book has three major aims. It is, first and foremost, a chronicle of the intense intellectual drama behind the outward serenity of this reinterpretation. Second, and by unavoidable implication, it is a statement about the nature of history and the awesome improbability of human evolution. As a third theme, I grapple with the enigma of why such a fundamental program of research has been permitted to pass so invisibly before the public gaze. Why is Opabinia, key animal in a new view of life, not a household name in all domiciles that care about the riddles of existence?

In short, Harry Whittington and his colleagues have shown that most Burgess organisms do not belong to familiar groups, and that the creatures from this single quarry in British Columbia probably exceed, in anatomical range, the entire spectrum of invertebrate life in today’s oceans. Some fifteen to twenty Burgess species cannot be allied with any known group, and should probably be classified as separate phyla. Magnify some of them beyond the few centimeters of their actual size, and you are on the set of a science-fiction film; one particularly arresting creature has been formally named Hallucigenia. For species that can be classified within known phyla, Burgess anatomy far exceeds the modern range. The Burgess Shale includes, for example, early representatives of all four major kinds of arthropods, the dominant animals on earth today—the trilobites (now extinct), the crustaceans (including lobsters, crabs, and shrimp), the chelicerates (including spiders and scorpions), and the uniramians (including insects). But the Burgess Shale also contains some twenty to thirty kinds of arthropods that cannot be placed in any modern group. Consider the magnitude of this difference: taxonomists have described almost a million species of arthropods, and all fit into four major groups; one quarry in British Columbia, representing the first explosion of multicellular life, reveals more than twenty additional arthropod designs! The history of life is a story of massive removal followed by differentiation within a few surviving stocks, not the conventional tale of steadily increasing excellence, complexity, and diversity.

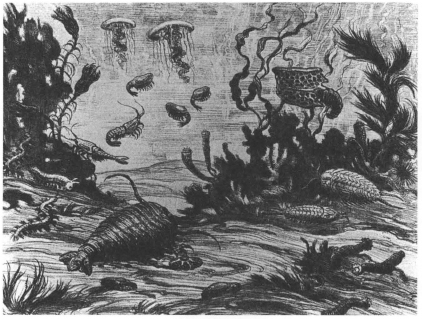

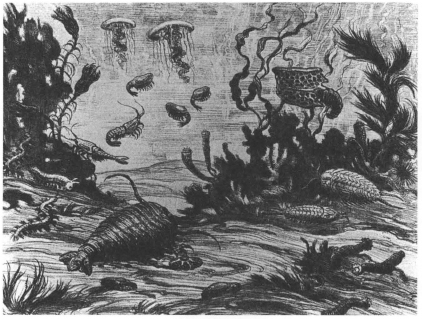

For an epitome of this new interpretation, compare Charles R. Knight’s restoration of the Burgess fauna (figure 1.1), based entirely on Walcott’s classification, with one that accompanied a 1985 article defending the reversed view (figure 1.2).

1.The centerpiece of Knight’s reconstruction is an animal named Sidneyia, largest of the Burgess arthropods known to Walcott, and an ancestral chelicerate in his view. In the modern version, Sidneyia has been banished to the lower right, its place usurped by Anomalocaris, a two foot-terror of the Cambrian seas, and one of the Burgess “unclassifiables.”

2.Knight restores each animal as a member of a well-known group that enjoyed substantial later success. Marrella is reconstructed as a trilobite, Waptia as a proto-shrimp (see figure 1.1), though both are ranked among the unplaceable arthropods today. The modern version features the unique phyla—giant Anomalocaris; Opabinia with its five eyes and frontal “nozzle”; Wiwaxia with its covering of scales and two rows of dorsal spines.

3.Knight’s creatures obey the convention of the “peaceable kingdom.” All are crowded together in an apparent harmony of mutual toleration; they do not interact. The modern version retains this unrealistic crowding (a necessary tradition for economy’s sake), but features the ecological relations uncovered by recent research: priapulid and polychaete worms burrow in the mud; the mysterious Aysheaia grazes on sponges; Anomalocaris everts its jaw and crunches a trilobite.

4.Consider Anomalocaris as a prototype for Whittington’s revision. Knight includes two animals omitted from the modern reconstruction: jellyfish and a curious arthropod that appears to be a shrimp’s rear end covered in front by a bivalved shell. Both represent errors committed in the overzealous attempt to shoehorn Burgess animals into modern groups. Walcott’s “jellyfish” turns out to be the circlet of plates surrounding the mouth of Anomalocaris; the posterior of his “shrimp” is a feeding appendage of the same carnivorous beast. Walcott’s prototypes for two modern groups become body parts of the largest Burgess oddball, the appropriately named Anomalocaris.

Thus a complex shift in ideas is epitomized by an alteration in pictures. Iconography is a neglected key to changing opinions, for the history and meaning of life in general, and for the Burgess Shale in stark particulars.

1.1. Reconstruction of the Burgess Shale fauna done by Charles R. Knight in 1940, probably the model for his 1942 restoration. All the animals are drawn as members of modern groups. Above Sidneyia, the largest animal of the scene, Waptia is reconstructed as a shrimp. Two parts that really belong to the unique creature Anomalocaris are portrayed respectively as an ordinary jellyfish (top, left of center) and the rear end of a bivalved arthropod (the large creature, center right, swimming above the two trilobites).

1.2. A modern reconstruction of the Burgess Shale fauna, illustrating an article by Briggs and Whittington on the genus Anomalocaris. This drawing, unlike Knight’s, features odd organisms. Sidneyia has been banished to the lower right, and the scene is dominated by two specimens of the giant Anomalocaris. Three Aysheaia feed on sponges along the lower border, left of Sidneyia. An Opabinia crawls along the bottom just left of Aysheaia. Two Wiwaxia graze on the sea floor below the upper Anomalocaris.

Familiarity has been breeding overtime in our mottoes, producing everything from contempt (according to Aesop) to children (as Mark Twain observed). Polonius, amidst his loquacious wanderings, urged Laertes to seek friends who were tried and true, and then, having chosen well, to “grapple them” to his “soul with hoops of steel.”

Yet, as Polonius’s eventual murderer stated in the most famous soliloquy of all time, “there’s the rub.” Those hoops of steel are not easily unbound, and the comfortably familiar becomes a prison of thought.

Words are our favored means of enforcing consensus; nothing inspires orthodoxy and purposeful unanimity of action so well as a finely crafted motto—Win one for the Gipper, and God shed his grace on thee. But our recent invention of speech cannot entirely bury an earlier heritage. Primates are visual animals par excellence, and the iconography of persuasion strikes even closer than words to the core of our being. Every demagogue, every humorist, every advertising executive, has known and exploited the evocative power of a well-chosen picture.

Scientists lost this insight somewhere along the way. To be sure, we use pictures more than most scholars, art historians excepted. Next slide please surpasses even It seems to me that as the most common phrase in professional talks at scientific meetings. But we view our pictures only as ancillary illustrations of what we defend by words. Few scientists would view an image itself as intrinsically ideological in content. Pictures, as accurate mirrors of nature, just are.

I can understand such an attitude directed toward photographs of objects—though opportunities for subtle manipulation are legion even here. But many of our pictures are incarnations of concepts masquerading as neutral descriptions of nature. These are the most potent sources of conformity, since ideas passing as descriptions lead us to equate the tentative with the unambiguously factual. Suggestions for the organization of thought are transformed to established patterns in nature. Guesses and hunches become things.

The familiar iconographies of evolution are all directed—sometimes crudely, sometimes subtly—toward reinforcing a comfortable view of human inevitability and superiority. The starkest version, the chain of being or ladder of linear progress, has an ancient, pre-evolutionary pedigree (see A. O. Lovejoy’s classic, The Great Chain of Being, 1936). Consider, for example, Alexander Pope’s Essay on Man, written early in the eighteenth century:

Far as creation’s ample range extends,

The scale of sensual, mental powers ascends:

Mark how it mounts, to man’s imperial race,

From the green myriads in the peopled grass.

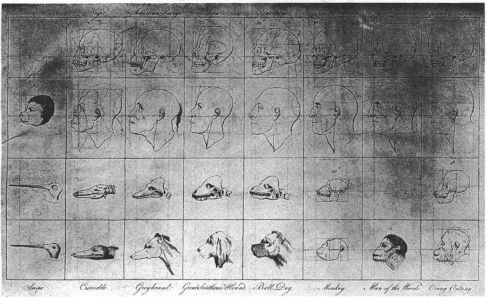

And note a famous version from the very end of that century (figure 1.3). In his Regular Gradation in Man, British physician Charles White shoehorned all the ramifying diversity of vertebrate life into a single motley sequence running from birds through crocodiles and dogs, past apes, and up the conventional racist ladder of human groups to a Caucasian paragon, described with the rococo flourish of White’s dying century:

Where shall we find, unless in the European, that nobly arched head, containing such a quantity of brain … ? Where the perpendicular face, the prominent nose, and round projecting chin? Where that variety of features, and fullness of expression, … those rosy cheeks and coral lips? (White, 1799).

1.3. The linear gradations of the chain of being according to Charles White (1799). A motley sequence runs from birds to crocodiles to dogs and monkeys (bottom two rows), and then up the conventional racist ladder of human groups (top two rows).

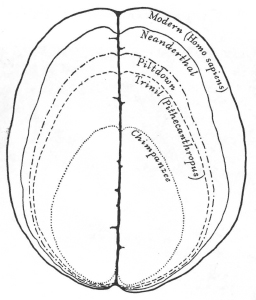

This tradition never vanished, even in our more enlightened age. In 1915, Henry Fairfield Osborn celebrated the linear accretion of cognition in a figure full of illuminating errors (figure 1.4). Chimps are not ancestors but modern cousins, equally distant in evolutionary terms from the unknown forebear of African great apes and humans. Pithecanthropus (Homo erectus in modern terms) is a potential ancestor, and the only legitimate member of the sequence. The inclusion of Piltdown is especially revealing. We now know that Piltdown was a fraud composed of a modern human cranium and an ape’s jaw. As a contemporary cranium, Piltdown possessed a brain of modern size; yet so convinced were Osborn’s colleagues that human fossils must show intermediate values on a ladder of progress, that they reconstructed Piltdown’s brain according to their expectations. As for Neanderthal, these creatures were probably close cousins belonging to a separate species, not ancestors. In any case, they had brains as large as ours, or larger, Osborn’s ladder notwithstanding.

1.4. Progress in the evolution of the human brain as illustrated by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1915.

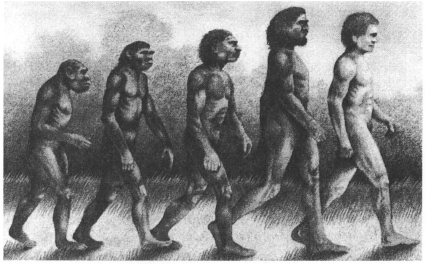

1.5. A personally embarrassing illustration of our allegiance to the iconography of the march of progress. My books are dedicated to debunking this picture of evolution, but I have no control over jacket designs for foreign translations. Four translations of my books have used the “march of human progress” as a jacket illustration. This is from the Dutch translation of Ever Since Darwin.

Nor have we abandoned this iconography in our generation. Consider figure 1.5, from a Dutch translation of one of my own books! The march of progress, single file, could not be more graphic. Lest we think that only Western culture promotes this conceit, I present one example of its spread (figure 1.6) purchased at the bazaar of Agra in 1985.

1.6. I bought this children’s science magazine in the bazaar of Agra, in India. The false iconography of the march of progress now has cross-cultural acceptance.

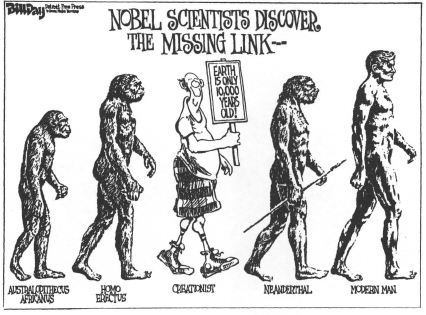

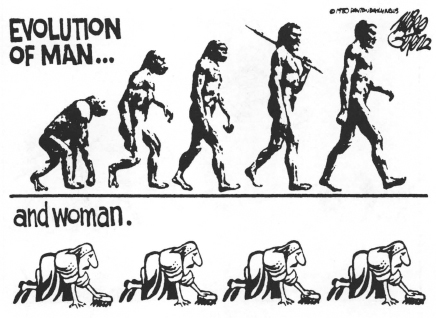

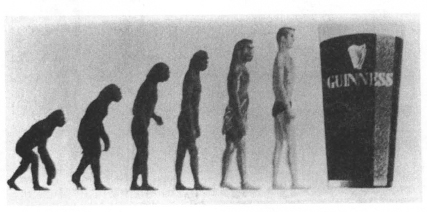

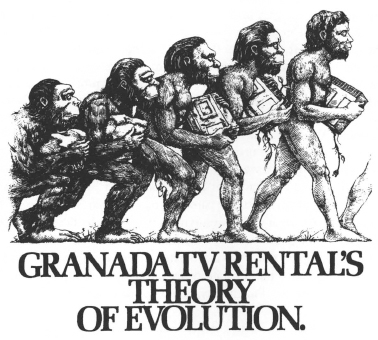

The march of progress is the canonical representation of evolution—the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all. This may best be appreciated by its prominent use in humor and in advertising. These professions provide our best test of public perceptions. Jokes and ads must click in the fleeting second that our attention grants them. Consider figure 1.7, a cartoon drawn by Larry Johnson for the Boston Globe before a Patriots–Raiders football game. Or figure 1.8, by the cartoonist Szep, on the proper place of terrorism. Or figure 1.9, by Bill Day, on “scientific creationism.” Or figure 1.10, by my friend Mike Peters, on the social possibilities traditionally open to men and to women. For advertising, consider the evolution of Guinness stout (figure 1.11) and of rental television (figure 1.12).*

1.7. A cartoonist can put the iconography of the ladder to good use. This example by Larry Johnson appeared in the Boston Globe before a Patriots–Raiders game.

The straitjacket of linear advance goes beyond iconography to the definition of evolution: the word itself becomes a synonym for progress. The makers of Doral cigarettes once presented a linear sequence of “improved” products through the years, under the heading “Doral’s theory of evolution.”† (Perhaps they are now embarrassed by this misguided claim, since they refused me permission to reprint the ad.) Or consider an episode from the comic strip Andy Capp (figure 1.13). Flo has no problem in accepting evolution, but she defines it as progress, and views Andy’s quadrupedal homecoming as quite the reverse.

1.8. World terrorism parachutes into its appropriate place in the march of progress. By Szep, in the Boston Globe.

1.9. A “scientific creationist” takes his appropriate place in the march of progress. By Bill Day, in the Detroit Free Press.

1.10. More mileage from the iconography of the ladder. By Mike Peters, in the Dayton Daily News. (Reprinted by permission of UFS, Inc.)

1.11. The highest stage of human advance as photographed from an English billboard.

Life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress. Most people may know this as a phrase to be uttered, but not as a concept brought into the deep interior of understanding. Hence we continually make errors inspired by unconscious allegiance to the ladder of progress, even when we explicitly deny such a superannuated view of life. For example, consider two errors, the second providing a key to our conventional misunderstanding of the Burgess Shale.

First, in an error that I call “life’s little joke” (Gould, 1987a), we are virtually compelled to the stunning mistake of citing unsuccessful lineages as classic “textbook cases” of “evolution.” We do this because we try to extract a single line of advance from the true topology of copious branching. In this misguided effort, we are inevitably drawn to bushes so near the brink of total annihilation that they retain only one surviving twig. We then view this twig as the acme of upward achievement, rather than the probable last gasp of a richer ancestry.

1.12. The march of progress as portrayed in another advertisement.

1.13. The vernacular equation of evolution with progress. Andy’s quadrupedal posture is interpreted as evolution in reverse. (By permission of © M.G.N. 1989, Syndication International/North America Syndicate, Inc.)

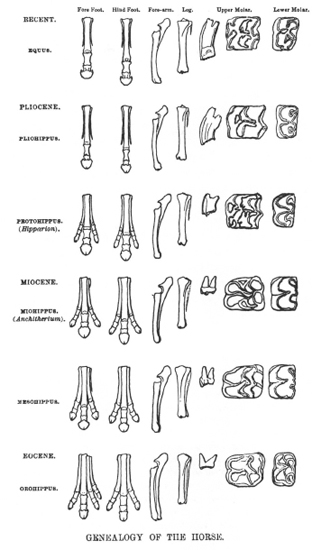

Consider the great warhorse of tradition—the evolutionary ladder of horses themselves (figure 1.14). To be sure, an unbroken evolutionary connection does link Hyracotherium (formerly called Eohippus) to modern Equus. And, yes again, modern horses are bigger, with fewer toes and higher crowned teeth. But Hyracotherium-Equus is not a ladder, or even a central lineage. This sequence is but one labyrinthine pathway among thousands on a complex bush. This particular route has achieved prominence for just one ironic reason—because all other twigs are extinct. Equus is the only twig left, and hence the tip of a ladder in our false iconography. Horses have become the classic example of progressive evolution because their bush has been so unsuccessful. We never grant proper acclaim to the real triumphs of mammalian evolution. Who ever hears a story about the evolution of bats, antelopes, or rodents—the current champions of mammalian life? We tell no such tales because we cannot linearize the bounteous success of these creatures into our favored ladder. They present us with thousands of twigs on a vigorous bush.

Need I remind everyone that at least one other lineage of mammals, especially dear to our hearts for parochial reasons, shares with horses both the topology of a bush with one surviving twig, and the false iconography of a march to progress?

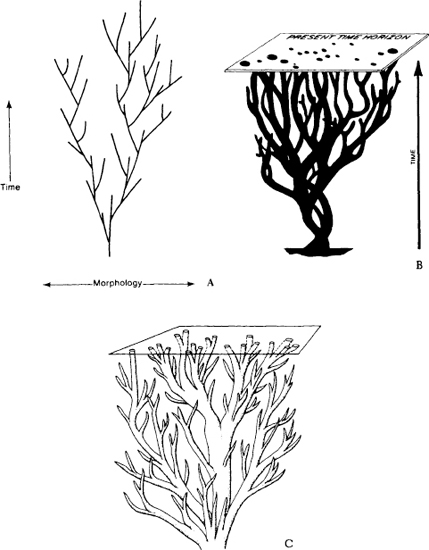

In a second great error, we may abandon the ladder and acknowledge the branching character of evolutionary lineages, yet still portray the tree of life in a conventional manner chosen to validate our hopes for predictable progress.

The tree of life grows with a few crucial constraints upon its form. First, since any well-defined taxonomic group can trace its origin to a single common ancestor, an evolutionary tree must have a unique basal trunk.* Second, all branches of the tree either die or ramify further. Separation is irrevocable; distinct branches do not join.†

1.14. The original version of the ladder of progress for horses, drawn by the American paleontologist O. C. Marsh for Thomas Henry Huxley after Marsh had shown his recently collected Western fossils to Huxley on his only visit to the United States. Marsh convinced his English visitor about this sequence, thus compelling Huxley to revamp his lecture on the evolution of horses given in New York in 1876. Note the steady decrease in number of toes and increase in height of teeth. Since Marsh drew all his specimens the same size, we do not see the other classical trend of increase in stature.

Yet, within these constraints of monophyly and divergence, the geometric possibilities for evolutionary trees are nearly endless. A bush may quickly expand to maximal width and then taper continuously, like a Christmas tree. Or it may diversify rapidly, but then maintain its full width by a continuing balance of innovation and death. Or it may, like a tumbleweed, branch helter-skelter in a confusing jumble of shapes and sizes.

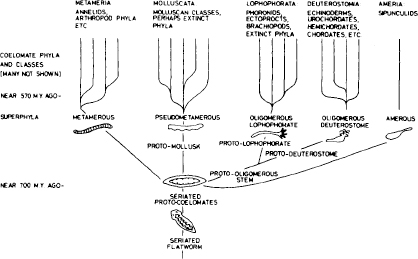

Ignoring these multifarious possibilities, conventional iconography has fastened upon a primary model, the “cone of increasing diversity,” an upside-down Christmas tree. Life begins with the restricted and simple, and progresses ever upward to more and more and, by implication, better and better. Figure 1.15 on the evolution of coelomates (animals with a body cavity, the subjects of this book), shows the orderly origin of everything from a simple flatworm. The stem splits to a few basic stocks; none becomes extinct; and each diversifies further, into a continually increasing number of subgroups.

1.15. A recent iconography for the evolution of coelomate animals, drawn according to the convention of the cone of increasing diversity (Valentine, 1977).

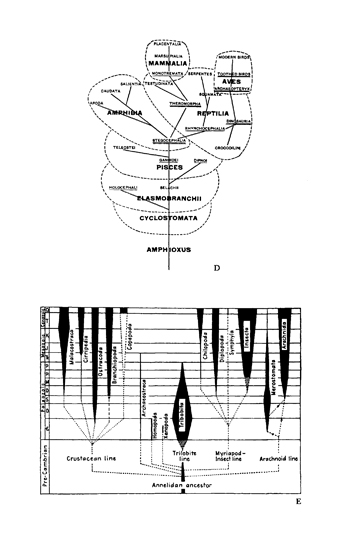

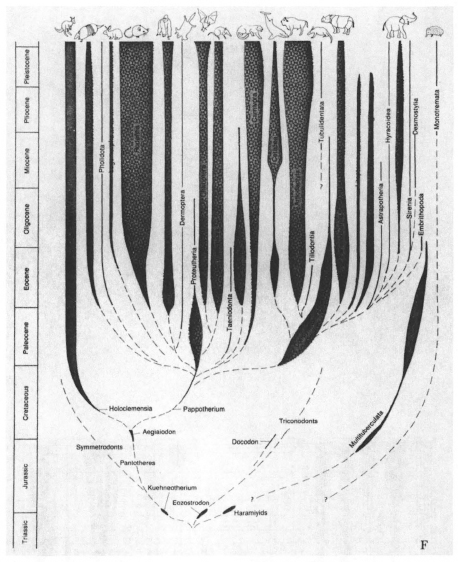

Figure 1.16 presents a panoply of cones drawn from popular modern textbooks—three abstract and three actual examples for groups crucial to the argument of this book. (In chapter IV, I discuss the origin of this model in Haeckel’s original trees and their influence upon Walcott’s great error in reconstructing the Burgess fauna.) All these trees show the same pattern: branches grow ever upward and outward, splitting from time to time. If some early lineages die, later gains soon overbalance these losses. Early deaths can eliminate only small branches near the central trunk. Evolution unfolds as though the tree were growing up a funnel, always filling the continually expanding cone of possibilities..

In its conventional interpretation, the cone of diversity propagates an interesting conflation of meanings. The horizontal dimension shows diversity—fishes plus insects plus snails plus starfishes at the top take up much more lateral room than just flatworms at the bottom. But what does the vertical dimension represent? In a literal reading, up and down should record only younger and older in geological time: organisms at the neck of the funnel are ancient; those at the lip, recent. But we also read upward movement as simple to complex, or primitive to advanced. Placement in time is conflated with judgment of worth.

Our ordinary discourse about animals follows this iconography. Nature’s theme is diversity. We live surrounded by coeval twigs of life’s tree. In Darwin’s world, all (as survivors in a tough game) have some claim to equal status. Why, then, do we usually choose to construct a ranking of implied worth (by assumed complexity, or relative nearness to humans, for example)? In a review of a book on courtship in the animal kingdom, Jonathan Weiner (New York Times Book Review, March 27, 1988) describes the author’s scheme of organization: “Working in loosely evolutionary order, Mr. Walters begins with horseshoe crabs, which have been meeting and mating on dark beaches in synchrony with tide and moon for 200 million years.” Later chapters make the “long evolutionary leap to the antics of the pygmy chimpanzee.” Why is this sequence called “evolutionary order”? Anatomically complex horseshoe crabs are not ancestral to vertebrates; the two phyla, Arthropoda and Chordata, have been separate from the very first records of multicellular life.

1.16. The iconography of the cone of increasing diversity, as seen in six examples from textbooks. All these diagrams are presented as simple objective portrayals of evolution; none are explicit representations of diversification as opposed to some other evolutionary process. Three abstract examples (A–C) are followed by conventional views of three specific phylogenies–vertebrate (D), arthropod (E), and mammalian (F, on p. 42). The data of the Burgess Shale falsify this central view of arthropod evolution as a continuous process of increasing diversification.

1.16 A conventional view of mammalian phylogeny.

In another recent example, showing that this error infests technical as well as lay discourse, an editorial in Science, the leading scientific journal in America, constructs an order every bit as motley and senseless as White’s “regular gradation” (see figure 1.3). Commenting on species commonly used for laboratory work, the editors discuss the “middle range” between unicellular creatures and guess who at the apex: “Higher on the evolutionary ladder,” we learn, “the nematode, the fly and the frog have the advantage of complexity beyond the single cell, but represent far simpler species than mammals” (June 10, 1988).

The fatuous idea of a single order amidst the multifarious diversity of modern life flows from our conventional iconographies and the prejudices that nurture them—the ladder of life and the cone of increasing diversity. By the ladder, horseshoe crabs are judged as simple; by the cone, they are deemed old.* And one implies the other under the grand conflation discussed above—down on the ladder also means old, while low on the cone denotes simple.

I don’t think that any particular secret, mystery, or inordinate subtlety underlies the reasons for our allegiance to these false iconographies of ladder and cone. They are adopted because they nurture our hopes for a universe of intrinsic meaning defined in our terms. We simply cannot bear the implications of Omar Khayyám’s honesty:

Into this Universe, and Why not knowing,

Nor whence, like Water willy-nilly flowing:

And out of it, as Wind along the Waste

I know not Whither, willy-nilly blowing.

A later quatrain of the Rubáiyát proposes a counteracting strategy, but acknowledges its status as a vain hope:

Ah Love! could you and I with Fate conspire

To grasp this sorry Scheme of Things entire,

Would we not shatter it to bits—and then

Re-mold it nearer to the Heart’s Desire!

Most myths and early scientific explanations of Western culture pay homage to this “heart’s desire.” Consider the primal tale of Genesis, presenting a world but a few thousand years old, inhabited by humans for all but the first five days, and populated by creatures made for our benefit and subordinate to our needs. Such a geological background could inspire Alexander Pope’s confidence, in the Essay on Man, about the deeper meaning of immediate appearances:

All Nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good.

But, as Freud observed, our relationship with science must be paradoxical because we are forced to pay an almost intolerable price for each major gain in knowledge and power—the psychological cost of progressive dethronement from the center of things, and increasing marginality in an uncaring universe. Thus, physics and astronomy relegated our world to a corner of the cosmos, and biology shifted our status from a simulacrum of God to a naked, upright ape.

To this cosmic redefinition, my profession contributed its own special shock—geology’s most frightening fact, we might say. By the turn of the last century, we knew that the earth had endured for millions of years, and that human existence occupied but the last geological millimicrosecond of this history—the last inch of the cosmic mile, or the last second of the geological year, in our standard pedagogical metaphors.

We cannot bear the central implication of this brave new world. If humanity arose just yesterday as a small twig on one branch of a flourishing tree, then life may not, in any genuine sense, exist for us or because of us. Perhaps we are only an afterthought, a kind of cosmic accident, just one bauble on the Christmas tree of evolution.

What options are left in the face of geology’s most frightening fact? Only two, really. We may, as this book advocates, accept the implications and learn to seek the meaning of human life, including the source of morality, in other, more appropriate, domains—either stoically with a sense of loss, or with joy in the challenge if our temperament be optimistic. Or we may continue to seek cosmic comfort in nature by reading life’s history in a distorted light.

If we elect the second strategy, our maneuvers are severely restricted by our geological history. When we infested all but the first five days of time, the history of life could easily be rendered in our terms. But if we wish to assert human centrality in a world that functioned without us until the last moment, we must somehow grasp all that came before as a grand preparation, a foreshadowing of our eventual origin.

The old chain of being would provide the greatest comfort, but we now know that the vast majority of “simpler” creatures are not human ancestors or even prototypes, but only collateral branches on life’s tree. The cone of increasing progress and diversity therefore becomes our iconography of choice. The cone implies predictable development from simple to complex, from less to more. Homo sapiens may form only a twig, but if life moves, even fitfully, toward greater complexity and higher mental powers, then the eventual origin of self-conscious intelligence may be implicit in all that came before. In short, I cannot understand our continued allegiance to the manifestly false iconographies of ladder and cone except as a desperate finger in the dike of cosmically justified hope and arrogance.

I leave the last word on this subject to Mark Twain, who grasped so graphically, when the Eiffel Tower was the world’s tallest building, the implications of geology’s most frightening fact:

Man has been here 32,000 years. That it took a hundred million years to prepare the world for him* is proof that that is what it was done for. I suppose it is. I dunno. If the Eiffel Tower were now representing the world’s age, the skin of paint on the pinnacle knob at its summit would represent man’s share of that age; and anybody would perceive that the skin was what the tower was built for. I reckon they would, I dunno.

The iconography of the cone made Walcott’s original interpretation of the Burgess fauna inevitable. Animals so close in time to the origin of multicellular life would have to lie in the narrow neck of the funnel. Burgess animals therefore could not stray beyond a strictly limited diversity and a basic anatomical simplicity. In short, they had to be classified either as primitive forms within modern groups, or as ancestral animals that might, with increased complexity, progress to some familiar form of the modern seas. Small wonder, then, that Walcott interpreted every organism in the Burgess Shale as a primitive member of a prominent branch on life’s later tree.

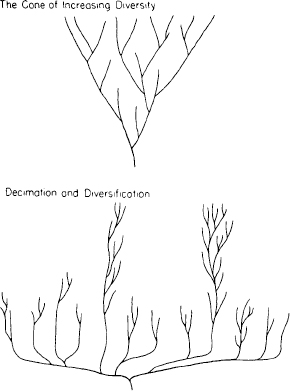

1.17. The false but still conventional iconography of the cone of increasing diversity, and the revised model of diversification and decimation, suggested by the proper reconstruction of the Burgess Shale.

I know no greater challenge to the iconography of the cone—and hence no more important case for a fundamentally revised view of life—than the radical reconstructions of Burgess anatomy presented by Whittington and his colleagues. They have literally followed our most venerable metaphor for revolution: they have turned the traditional interpretation on its head. By recognizing so many unique anatomies in the Burgess, and by showing that familiar groups were then experimenting with designs so far beyond the modern range, they have inverted the cone. The sweep of anatomical variety reached a maximum right after the initial diversification of multicellular animals. The later history of life proceeded by elimination, not expansion. The current earth may hold more species than ever before, but most are iterations upon a few basic anatomical designs. (Taxonomists have described more than a half million species of beetles, but nearly all are minimally altered Xeroxes of a single ground plan.) In fact, the probable increase in number of species through time merely underscores the puzzle and paradox. Compared with the Burgess seas, today’s oceans contain many more species based upon many fewer anatomical plans.

Figure 1.17 presents a revised iconography reflecting the lessons of the Burgess Shale. The maximum range of anatomical possibilities arises with the first rush of diversification. Later history is a tale of restriction, as most of these early experiments succumb and life settles down to generating endless variants upon a few surviving models.*

This inverted iconography, however interesting and radical in itself, need not imply a revised view of evolutionary predictability and direction. We can abandon the cone, and accept the inverted iconography, yet still maintain full allegiance to tradition if we adopt the following interpretation: all but a small percentage of Burgess possibilities succumbed, but the losers were chaff, and predictably doomed. Survivors won for cause—and cause includes a crucial edge in anatomical complexity and competitive ability.

But the Burgess pattern of elimination also suggests a truly radical alternative, precluded by the iconography of the cone. Suppose that winners have not prevailed for cause in the usual sense. Perhaps the grim reaper of anatomical designs is only Lady Luck in disguise. Or perhaps the actual reasons for survival do not support conventional ideas of cause as complexity, improvement, or anything moving at all humanward. Perhaps the grim reaper works during brief episodes of mass extinction, provoked by unpredictable environmental catastrophes (often triggered by impacts of extraterrestrial bodies). Groups may prevail or die for reasons that bear no relationship to the Darwinian basis of success in normal times. Even if fishes hone their adaptations to peaks of aquatic perfection, they will all die if the ponds dry up. But grubby old Buster the Lungfish, former laughingstock of the piscine priesthood, may pull through—and not because a bunion on his great-grandfather’s fin warned his ancestors about an impending comet. Buster and his kin may prevail because a feature evolved long ago for a different use has fortuitously permitted survival during a sudden and unpredictable change in rules. And if we are Buster’s legacy, and the result of a thousand other similarly happy accidents, how can we possibly view our mentality as inevitable, or even probable?

We live, as our humorists proclaim, in a world of good news and bad news. The good news is that we can specify an experiment to decide between the conventional and the radical interpretations of extinction, thereby settling the most important question we can ask about the history of life. The bad news is that we can’t possibly perform the experiment.

I call this experiment “replaying life’s tape.” You press the rewind button and, making sure you thoroughly erase everything that actually happened, go back to any time and place in the past—say, to the seas of the Burgess Shale. Then let the tape run again and see if the repetition looks at all like the original. If each replay strongly resembles life’s actual pathway, then we must conclude that what really happened pretty much had to occur. But suppose that the experimental versions all yield sensible results strikingly different from the actual history of life? What could we then say about the predictability of self-conscious intelligence? or of mammals? or of vertebrates? or of life on land? or simply of multicellular persistence for 600 million difficult years?

THE MEANINGS OF DIVERSITY AND DISPARITY

I must introduce at this point an important distinction that should allay a classic source of confusion. Biologists use the vernacular term diversity in several different technical senses. They may talk about “diversity” as number of distinct species in a group: among mammals, rodent diversity is high, more than 1,500 separate species; horse diversity is low, since zebras, donkeys, and true horses come in fewer than ten species. But biologists also speak of “diversity” as difference in body plans. Three blind mice of differing species do not make a diverse fauna, but an elephant, a tree, and an ant do—even though each assemblage contains just three species.

The revision of the Burgess Shale rests upon its diversity in this second sense of disparity in anatomical plans. Measured as number of species, Burgess diversity is not high. This fact embodies a central paradox of early life: How could so much disparity in body plans evolve in the apparent absence of substantial diversity in number of species?—for the two are correlated, more or less in lockstep, by the iconography of the cone (see figure 1.16).

When I speak of decimation, I refer to reduction in the number of anatomical designs for life, not numbers of species. Most paleontologists agree that the simple count of species has augmented through time (Sepkoski et al., 1981)—and this increase of species must therefore have occurred within a reduced number of body plans.

Most people do not fully appreciate the stereotyped character of current life. We learn lists of odd phyla in high school, until kinorhynch, priapulid, gnathostomulid, and pogonophoran roll off the tongue (at least until the examination ends). Focusing on a few oddballs, we forget how unbalanced life can be. Nearly 80 percent of all described animal species are arthropods (mostly insects). On the sea floor, once you enumerate polychaete worms, sea urchins, crabs, and snails, there aren’t that many coelomate invertebrates left. Stereotypy, or the cramming of most species into a few anatomical plans, is a cardinal feature of modern life—and its greatest difference from the world of Burgess times.

Several of my colleagues (Jaanusson, 1981; Runnegar, 1987) have suggested that we eliminate the confusion about diversity by restricting this vernacular term to the first sense—number of species. The second sense—difference in body plans—should then be called disparity. Using this terminology, we may acknowledge a central and surprising fact of life’s history—marked decrease in disparity followed by an outstanding increase in diversity within the few surviving designs.

We can now appreciate the central importance of the Burgess revision and its iconography of decimation. With the ladder or the cone, the issue of life’s tape does not arise. The ladder has but one bottom rung, and one direction. Replay the tape forever, and Eohippus will always gallop into the sunrise, bearing its ever larger body on fewer toes. Similarly, the cone has a narrow neck and a restricted range of upward movement. Rewind the tape back into the neck of time, and you will always obtain the same prototypes, constrained to rise in the same general direction.

But if a radical decimation of a much greater range of initial possibilities determined the pattern of later life, including the chance of our own origin, then consider the alternatives. Suppose that ten of a hundred designs will survive and diversify. If the ten survivors are predictable by superiority of anatomy (interpretation 1), then they will win each time—and Burgess eliminations do not challenge our comforting view of life. But if the ten survivors are protégés of Lady Luck or fortunate beneficiaries of odd historical contingencies (interpretation 2), then each replay of the tape will yield a different set of survivors and a radically different history. And if you recall from high-school algebra how to calculate permutations and combinations, you will realize that the total number of combinations for 10 items from a pool of 100 yields more than 17 trillion potential outcomes. I am willing to grant that some groups may have enjoyed an edge (though we have no idea how to identify or define them), but I suspect that the second interpretation grasps a central truth about evolution. The Burgess Shale, in making this second interpretation intelligible by the hypothetical experiment of the tape, promotes a radical view of evolutionary pathways and predictability.

Rejection of ladder and cone does not throw us into the arms of a supposed opposite—pure chance in the sense of coin tossing or of God playing dice with the universe. Just as the ladder and the cone are limiting iconographies for life’s history, so too does the very idea of dichotomy grievously restrict our thinking. Dichotomy has its own unfortunate iconography—a single line embracing all possible opinions, with the two ends representing polar opposites—in this case, determinism and randomness.

An old tradition, dating at least to Aristotle, advises the prudent person to stake out a position comfortably toward the middle of the line—the aurea mediocritas (“golden mean”). But in this case the middle of the line has not been so happy a place, and the game of dichotomy has seriously hampered our thinking about the history of life. We may understand that the older determinism of predictable progress cannot strictly apply, but we think that our only alternative lies with the despair of pure randomness. So we are driven back toward the old view, and finish, with discomfort, at some ill-defined confusion in between.

I strongly reject any conceptual scheme that places our options on a line, and holds that the only alternative to a pair of extreme positions lies somewhere between them. More fruitful perspectives often require that we step off the line to a site outside the dichotomy.

I write this book to suggest a third alternative, off the line. I believe that the reconstructed Burgess fauna, interpreted by the theme of replaying life’s tape, offers powerful support for this different view of life: any replay of the tape would lead evolution down a pathway radically different from the road actually taken. But the consequent differences in outcome do not imply that evolution is senseless, and without meaningful pattern; the divergent route of the replay would be just as interpretable, just as explainable after the fact, as the actual road. But the diversity of possible itineraries does demonstrate that eventual results cannot be predicted at the outset. Each step proceeds for cause, but no finale can be specified at the start, and none would ever occur a second time in the same way, because any pathway proceeds through thousands of improbable stages. Alter any early event, ever so slightly and without apparent importance at the time, and evolution cascades into a radically different channel.

This third alternative represents no more nor less than the essence of history. Its name is contingency—and contingency is a thing unto itself, not the titration of determinism by randomness. Science has been slow to admit the different explanatory world of history into its domain—and our interpretations have been impoverished by this omission. Science has also tended to denigrate history, when forced to a confrontation, by regarding any invocation of contingency as less elegant or less meaningful than explanations based directly on timeless “laws of nature.”

This book is about the nature of history and the overwhelming improbability of human evolution under themes of contingency and the metaphor of replaying life’s tape. It focuses upon the new interpretation of the Burgess Shale as our finest illustration of what contingency implies in our quest to understand the evolution of life.

I concentrate upon details of the Burgess Shale because I don’t believe that important concepts should be discussed tendentiously in the abstract (much as I have disobeyed the rule in this opening chapter!). People, as curious primates, dote on concrete objects that can be seen and fondled. God dwells among the details, not in the realm of pure generality. We must tackle and grasp the larger, encompassing themes of our universe, but we make our best approach through small curiosities that rivet our attention—all those pretty pebbles on the shoreline of knowledge. For the ocean of truth washes over the pebbles with every wave, and they rattle and clink with the most wondrous din.

We can argue about abstract ideas forever. We can posture and feint. We can “prove” to the satisfaction of one generation, only to become the laughingstock of a later century (or, worse still, to be utterly forgotten). We may even validate an idea by grafting it permanently upon an object of nature—thus participating in the legitimate sense of a great human adventure called “progress in scientific thought.”

But the animals of the Burgess Shale are somehow even more satisfying in their adamantine factuality. We will argue forever about the meaning of life, but Opabinia either did or did not have five eyes—and we can know for certain one way or the other. The animals of the Burgess Shale are also the world’s most important fossils, in part because they have revised our view of life, but also because they are objects of such exquisite beauty. Their loveliness lies as much in the breadth of ideas that they embody, and in the magnitude of our struggle to interpret their anatomy, as in their elegance of form and preservation.

The animals of the Burgess Shale are holy objects—in the unconventional sense that this word conveys in some cultures. We do not place them on pedestals and worship from afar. We climb mountains and dynamite hillsides to find them. We quarry them, split them, carve them, draw them, and dissect them, struggling to wrest their secrets. We vilify and curse them for their damnable intransigence. They are grubby little creatures of a sea floor 530 million years old, but we greet them with awe because they are the Old Ones, and they are trying to tell us something.