Imagine this: you’ve just woken up and found yourself alone, on top of a hill. You stand up. You have no idea where you are or how you got there. Let’s throw in some fog. There, it’s foggy. You need to get home, but to do that you need to figure out where you are. What do you do first? You look around.

Pennie, Penrose, Kate, Warren. Just some of the names my mother goes by.

Family history, to begin with, is much the same. You start by taking a look around. You need to check the ground beneath your feet, to check what you’re standing on is firm. You need to remove any assumptions, you need to try and forget everything you think you know and concentrate on facts. And very slowly, like a person with arms outstretched feeling their way through a foggy landscape, you move from the known into the unknown, checking your footing with every step.

Take your mother’s first name. Most of you will assume you know your mother’s first name. But do you actually know it? Do you have her name recorded on a birth certificate nestled away in your family archive? Can you lay your hands on irreversible proof that the name you have just jotted down is the same as the name that the state holds?

If you had met me just fifteen years ago and asked me my mother’s first name, the answer I would have given you would have been wrong. Indeed, the answer she would give you today would not be the same as the answer the state would give. I was in my twenties by the time I finally picked up a letter and asked: ‘Why does your bank always call you Kate?’ I was expecting a tale of misunderstanding never put right, but it turned out her name is Kate. It was the name she was born with, baptised with and registered with, just not the name she ever went by. And this is more common than you might think. People often don’t go by the names they were given. I went to school with a boy who veered between calling himself Simon (his middle name) and Piers (his first name).

‘I can trace my family back to 1066 don’t you know!’ The author as irritating youth.

When you enter the first antechamber of genealogical research you not only need be aware of what you don’t yet know, but also what you think you already know. It may sound unimportant, but checking birth, marriage and death indexes is the first chore for many a researcher, and it’s amazing just how many family historians are almost immediately thwarted – often because of erroneous assumptions and family myths. As an irritating, corduroyed youth, I would boast to anyone who would listen that I could trace my family back to 1066. In the words of my former editor Simon Fowler, that turned out to be ‘rubbish’. (He actually used a different word.)

Now, this book is aimed at researchers from all over the world tracing British and Irish roots, the emphasis being toward readers who can’t easily travel here to conduct research first hand. That’s not to say I will ignore physical sources that have to be checked in person – far from it – but the focus will predominantly be on sources, services, finding aids and advice that can be found online.

Go to wherever you keep your old stuff and take it out. If you don’t have any kind of family archive, don’t worry, just skip to the next chapter. But if you do, dive in, lay it all over a carpeted floor while a radio plays something you like, and organise it into categories. Your categories could be Immediate Family (if you find the short-form birth certificate of your mother, put this here), Wider Family (a named photograph of a great uncle in his service uniform would be put here), Unknown (for any unnamed photographs/items) and Miscellaneous (for random ephemera such as ancient bills or uniform buttons).

Now start drawing up a very rough family tree, with all the names of members of your immediate family, then spreading out to the next generation. To begin with I’d suggest drawing this up free hand, but you can of course print out all kinds of blank trees from the Internet if you prefer, or go straight to your computer and enter the details there.

Write down all the birth, marriage and death dates that you think you know. I suggest a colour code: black for certainties, pencil for virtual certainties that you need to double check and red for blind assumptions.

In the next section I go into a little more detail about the process of interviewing family members, but in general I’d advise that you remain suspicious of memories, including your own. Humans are excellent at combining memories, stealing other people’s and incorporating them into their own, and distorting time. Family legends are like that. My grandfather could certainly claim an association with legendary flying ace Douglas Bader (they both worked for Shell), but I suspect sometimes that the stories were expanded.

In short: don’t assume and watch out.

Right from the start you will need to be sensitive. There may be secrets just beneath the surface of your family’s party line. Some may benefit from an airing, others might not be ready to come out.

Now there are lots of books that concentrate on first steps, so I’m not going to spend too long repeating the tips and cliches, but I will end this section by suggesting some of my favourite on and offline sources. In general I find the writing of genealogical scribes Kathy Chater, Chris Paton, Simon Fowler, John Grenham, Anthony Adolph and Nick Barratt friendly, clear and easy to follow, and all focus on British-centric resources in the main. They each have strengths too – Chris is a font of knowledge on all things Scottish, John is the man for Irish research.

FamilySearch, Getting Started: familysearch.org/ask/gettingstarted

ScotlandsPeople > Help & Resources > Getting Started: scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Federation of Family History Societies, Really Useful Leaflet: ffhs.org.uk/really_useful_leaflet.pdf

Free UK Genealogy: freeukgenealogy.org.uk

FamilySearch, Research Forms: familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Research_Forms

FamilyTree, Getting Started: family-tree.co.uk/getting-started/

Genuki: genuki.org.uk/gs/

Society of Genealogists, Getting Started: sog.org.uk/learn/help-getting-started-with-genealogy/

Cyndi’s List, Getting Started: cyndislist.com/free-stuff/getting-started/

Ancestry, Getting Started: ancestry.co.uk/cs/uk/gettingstarted

British Genealogy Network: britishgenealogy.net

PRONI, Getting Started: www.proni.gov.uk/index/family_history/family_history_getting_started.htm

Adolph, Anthony. Collins Tracing Your Family History, Collins, 2008

Barratt, Nick. Who Do You Think You Are? Encyclopedia of Genealogy, Harper, 2008

Chater, Kathy. How to Trace Your Family Tree, Lorenz Books, 2013

Fowler, Simon. Family History: Digging Deeper, The History Press, 2012

Waddell, Dan. Who Do You Think You Are?: The Genealogy Handbook, BBC Books, 2014

All you need to begin with is a large piece of paper and a pencil. Websites, software and mobile apps will be clamouring for you to enter names and dates into their online family trees. This is a great option, but I would wait until you have your immediate family and perhaps one generation back nailed before going digital.

You’ve already gathered together what documentary evidence and photographs exist in your family archives – certificates, diaries, letters and photographs. Alongside your large piece of paper, you should arm yourself with an A5 reporter’s notebook or an A4 legal pad (or some method of digital note taking). And this is the most important thing to remember: start writing everything down.

Keeping notes becomes increasingly important as you delve further into an individual’s life, so you need to start out as you mean to carry on. If you hear from aunt so-and-so that great uncle so-and-so played first-class cricket for Glamorgan in 1948, then write down the fact and where/when it came from. The most frustrating thing about family history is when you do a little digging, then life takes over and you don’t touch your research for a month or two, and before you know it, you’re spending an afternoon re-treading the same path.

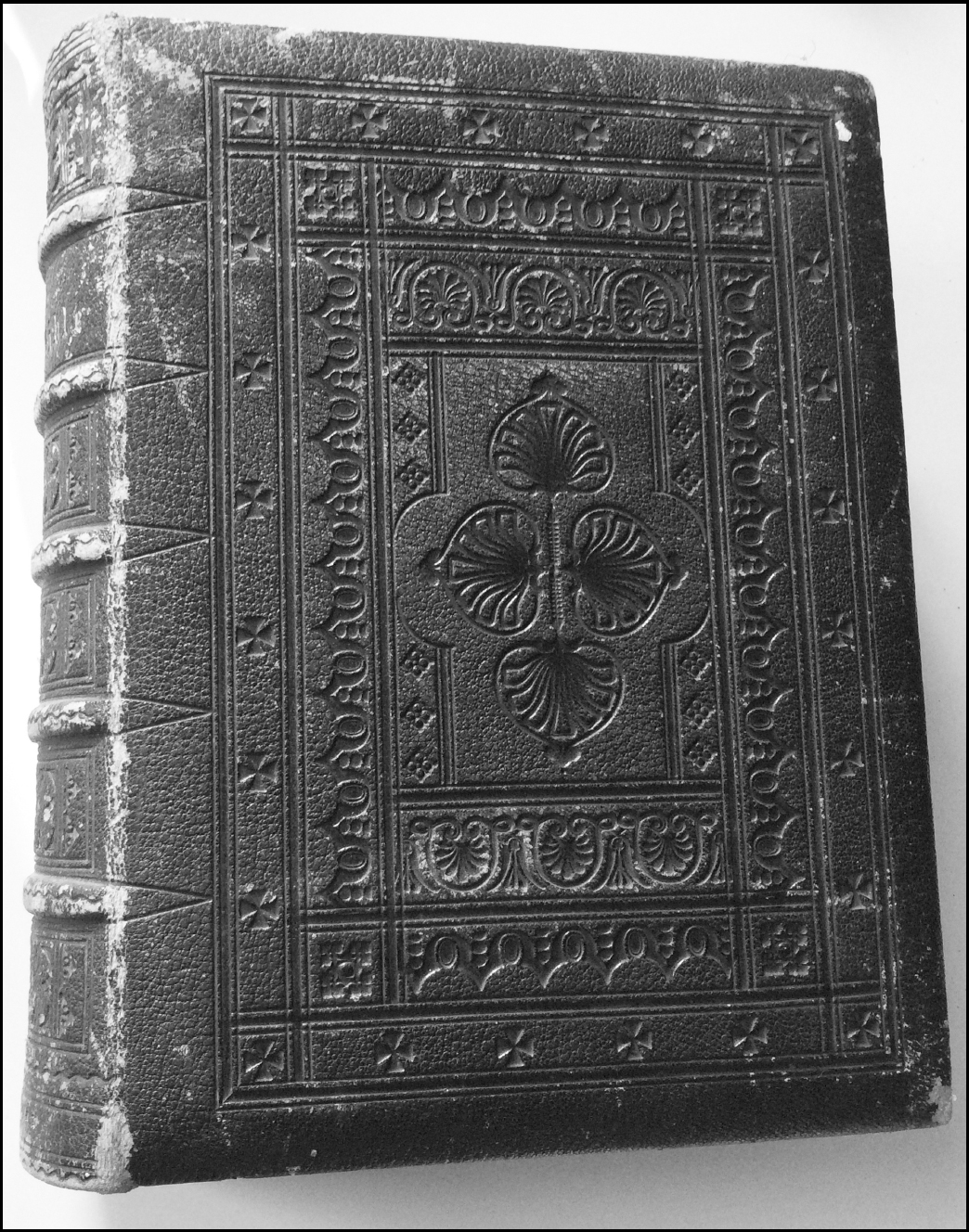

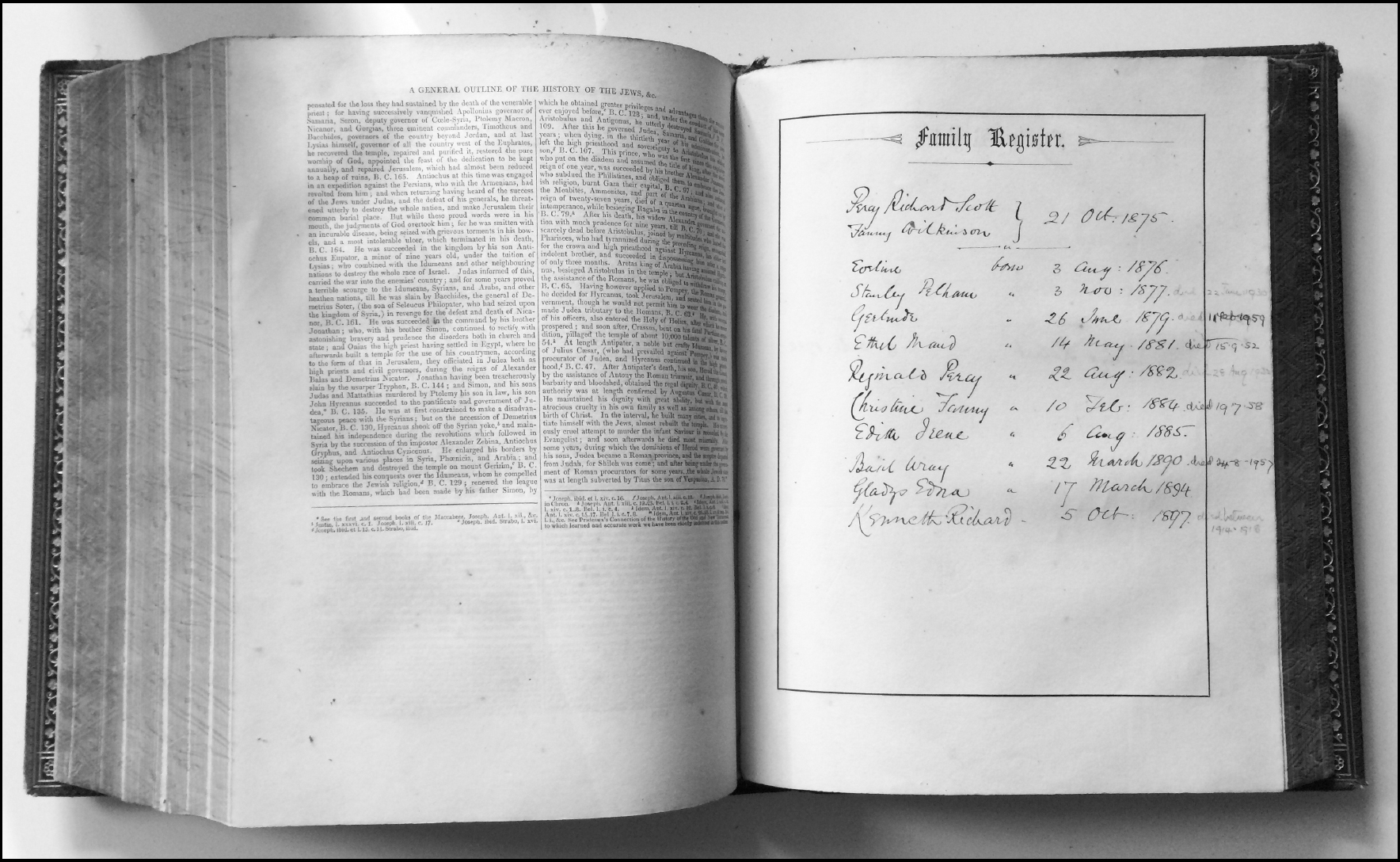

Family bibles can be excellent sources of information, often including detailed family trees. This Victorian example has Family Register pages sandwiched between the Old and New Testaments.

You need to be in the habit of noting not only the facts/information you gather, but also where you gathered them from – your sources. Just as importantly you need to note down not only the searches that lead to fruitful information, but also those that turn up nothing. The only thing more annoying than a blind alley, is a blind alley you’ve been down before.

Now many starting out guides include tips that say the likes of ‘check whether anyone has already researched your tree’. I’ve never quite understood this, as it seems like such a double-edged sword. Yes, it will save you work, but you’re only saving yourself from the very thing you’re setting out to do. It’s like setting out on a marathon, only to decide that as all these other people are running it you don’t need to.

That said, if someone’s been there before it will of course save you much of the tedious early leg-work, meaning you can concentrate on the more ‘fun’ aspects of genealogy. But, at the same time, fixing names and dates of individuals is a vital learning curve that everyone needs to go through. So, even if you do find yourself presented with a fairly complete family tree, I’d still suggest you go back to the sources and double-check names and dates for yourself.

Assuming you have some names and dates, notes on other information such as military service or occupation, plus some notes/reminders concerning any family stories or anecdotes that you want to check, it’s time to begin the family interviews.

If you’re in close contact with relatives and can begin your interviews with relative ease, I recommend getting to it, but taking a belt and braces approach – some kind of simple audio recorder plus a notebook. If you live miles or continents away from your nearest and dearest, then some email or handwritten correspondence will be called for. Make sure, however, that if you go for this latter method that you are specific about the questions you want answered. It’s easy to sound vague when writing an email requesting information, and vague questions will lead to vague answers. Many genealogists start out by drawing up a simple questionnaire, or printing out a ready made template of questions from websites such as FamilySearch, and as jumping off points these function very well.

When talking to relatives an open and flexible approach is best. You need to be flexible in terms of timings, but also in terms of what you are ready and willing to hear. The individual may not wish to talk about what you want to ask about. Listening carefully, taking time, will all help you get the most out of your interviewees.

When I started out as a local reporter, one of my many bad habits was the habit of excitedly jumping in with my own story during an interview. This, I soon realised, was a derailing thing to do. It can often blow conversations off course. By all means chip in, but you need to hold yourself back, to try not to interrupt and to listen. Everyone thinks they are good listeners, including me, but it’s an underrated skill that takes effort. Imagine you’re nearest and dearest is talking to you, while you’re watching television. Yes, you may be able to repeat back everything they have just said, but they won’t feel listened to. To listen, and to show that you’re listening, you need to give eye contact, you need to repeat back what you’ve heard to check you’re understanding. In other words, you need to pull the conversation, rather than push.

If you’re using recording devices (which I would recommend), you need to be up front. Make it clear that you will be recording what they say, and check this is alright with the interviewee. If it’s not, put it away and take notes. You will have to wait for them to settle into the conversation. Knowing one is being recorded, or just having someone making notes as you speak, can be an unsettling experience at first. You need to give people time to get used to it.

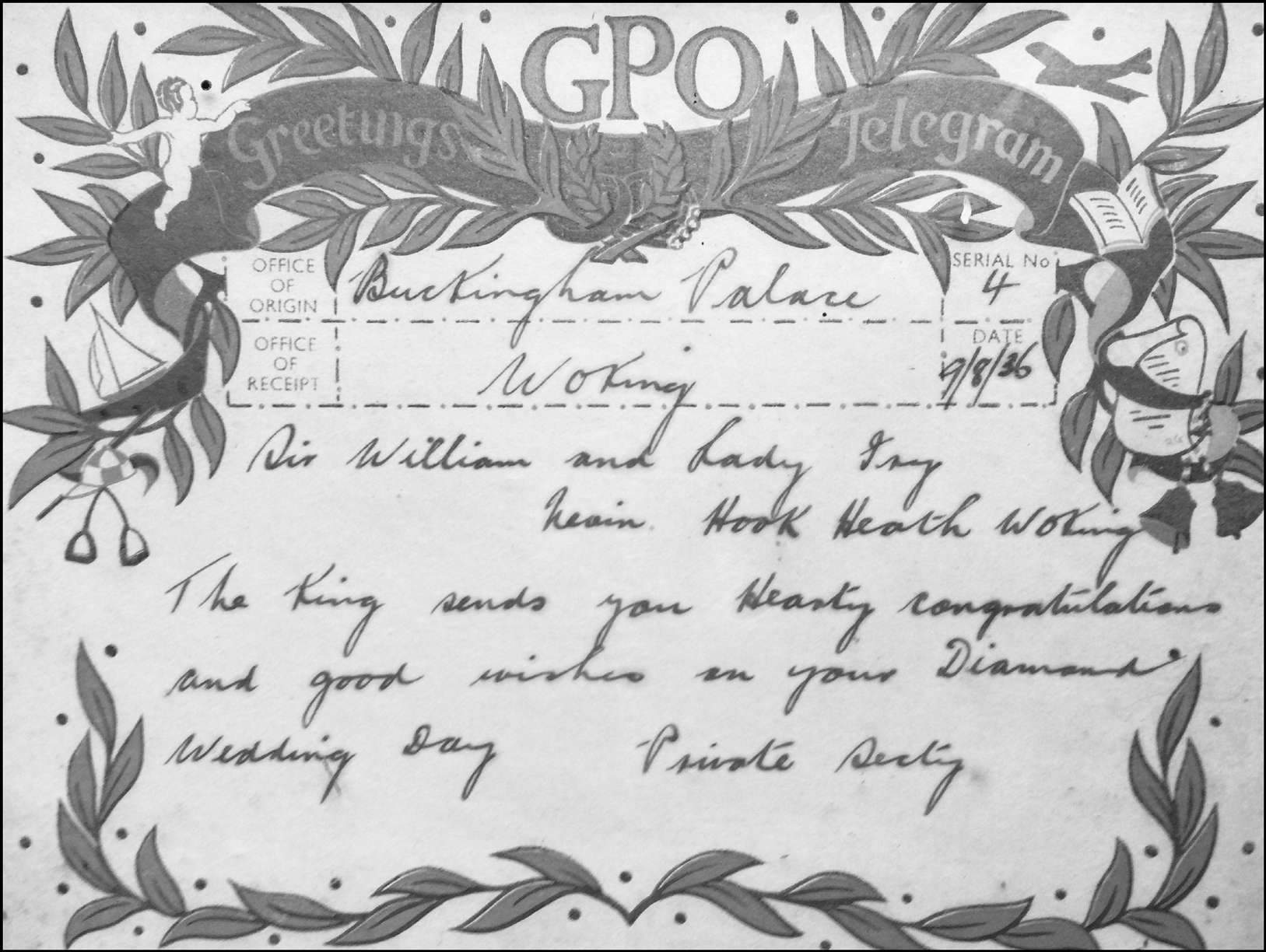

A congratulatory diamond wedding telegram from King Edward VIII, sent just months before his abdication.

You may go there determined to fix a date, but you also need to be open to what is being said. You may want to be specific, but giving space may lead to valuable but unexpected information. You need a spectrum of questions that range from the specific to the more general: from the ‘where were you born?’ to the ‘what do you remember about ____?’

Memories are imperfect. People’s perception of time can be particularly troublesome – an incident from two years ago can seem like a decade ago, an incident from decades before, can seem like yesterday. Memories can bunch together, can disguise themselves, can lie. So, you need to take everything with a pinch of salt. That’s not to say you should be cynical and doubting, but simply that you must take a rigorous approach to sifting what information comes in, to sort out what is known, and what remains hazy, what’s hearsay and what needs to be checked.

Families come complete with skeletons, secrets, scandals, rifts, divides, jealousies and neuroses. When you start out on your mission to find out more, just be aware of the feelings of your family. If you encounter resistance, respect the resistance and give it time.

During these interviews, you may be shown, or might ask to see, pieces of documentary evidence. You will need to write down the most important information contained within, and describe exactly where it comes from. You could also ask permission to borrow or copy the items. Again, if you bring along a camera, have a tablet computer or smartphone, you can quickly and easily take a perfectly serviceable copy right then and there. But again, be sensitive. People may be unwilling or uneasy about having precious photographs or items relating to loved ones out of their hands, or even copied.

Another decision to make at this early stage is your research goal. Do you intend to just go back as far as you can? Or perhaps there’s a particular family legend you wish to investigate. Having an achievable and manageable goal will help give shape and direction to your research. Many start by concentrating on a particular branch of the family, while others might choose just one period of one person’s life – such as an individual’s wartime service career.

● Work from what you know.

● Fix and confirm dates of birth, marriage and death, then work backwards.

● If you’re starting out and have several branches of the family to choose from, opt for the branch with the rarer surname. A less common surname makes your work much easier – great when you’re learning the ropes.

● Talk to relatives. Watch out for any nicknames and name changes. Ask to see any photos, letters or documents.

● If possible record your interviews.

● Take too many notes. You just never know what will come in useful when. So take a thorough approach and note everything down.

● Have a manageable goal. Perhaps choose a branch of the family or an individual to focus on.

● Check if anyone else is researching your family – you could at this point sign up to the likes of MyHeritage or GenesReunited, which can help you find researchers with shared interests.

● Focus on identifying when and where a person lived. Most records generated about a person will be associated with a place.

About.com, 50 Questions to Ask Your Relatives: genealogy.about.com/cs/oralhistory/a/interview.htm

FamilySearch, Creating oral histories: familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Creating_Oral_Histories

Oral History Society: www.ohs.org.uk

My intention in this section is to arm you with a rough and ready guide to the way the parish, county and state function together. I won’t bog you down with lots of information you don’t need, but a working knowledge of local government and ecclesiastical administration and boundaries will help you find records, interpret those records and predict possible pitfalls before they happen. If you’re on an expensive research trip to some county record office, it would be rather frustrating to learn that the parish material you seek is in the diocesan record office 50 miles away, or that the parish you thought was in one county, turns out to share its name with the small chapelry in a neighbouring county.

There are differences in the structure of local government across the constituent parts of the UK partly because they each derive from systems in place prior to unification. It wasn’t until the population explosion of the Industrial Revolution that some systems of local government were reformed, modernised and partially unified.

If you read nothing else in this book, simply hold on to this piece of advice: spend some time confirming the location of your ancestor’s home parish, and then confirm the location of records relating to that parish. If you’re at all familiar with military research, you will know that ‘the unit’ is the basic currency – know the unit in which an individual served and this gives you the keys to the city. Similarly, with much genealogical research, the parish is the vital thing to know.

Local expertise is invaluable. There are many regional quirks and inconstancies, with shifting boundaries of parish, hundred, diocese and county, coupled with further confusion over types of boundary (ecclesiastical, civil, poor law, etc.), which can unsettle researchers new to an area. This is where the network of county family history societies, each with their own pools of expertise, can really come into their own.

First let’s go top-down through the basic administrative divisions: Country/State/Parliament > County/Shire > Borough/District > Hundred > Parish. Meanwhile, in England, ecclesiastical units can be summarised: Church of England > Province (Canterbury and York) > Archdiocese > Diocese/bishopric > Parish.

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of England was divided into ‘shires’ – the shire being the traditional term for a division of land. Today those shires are known as counties – which is why so many British counties have ‘shire’ within their county names.

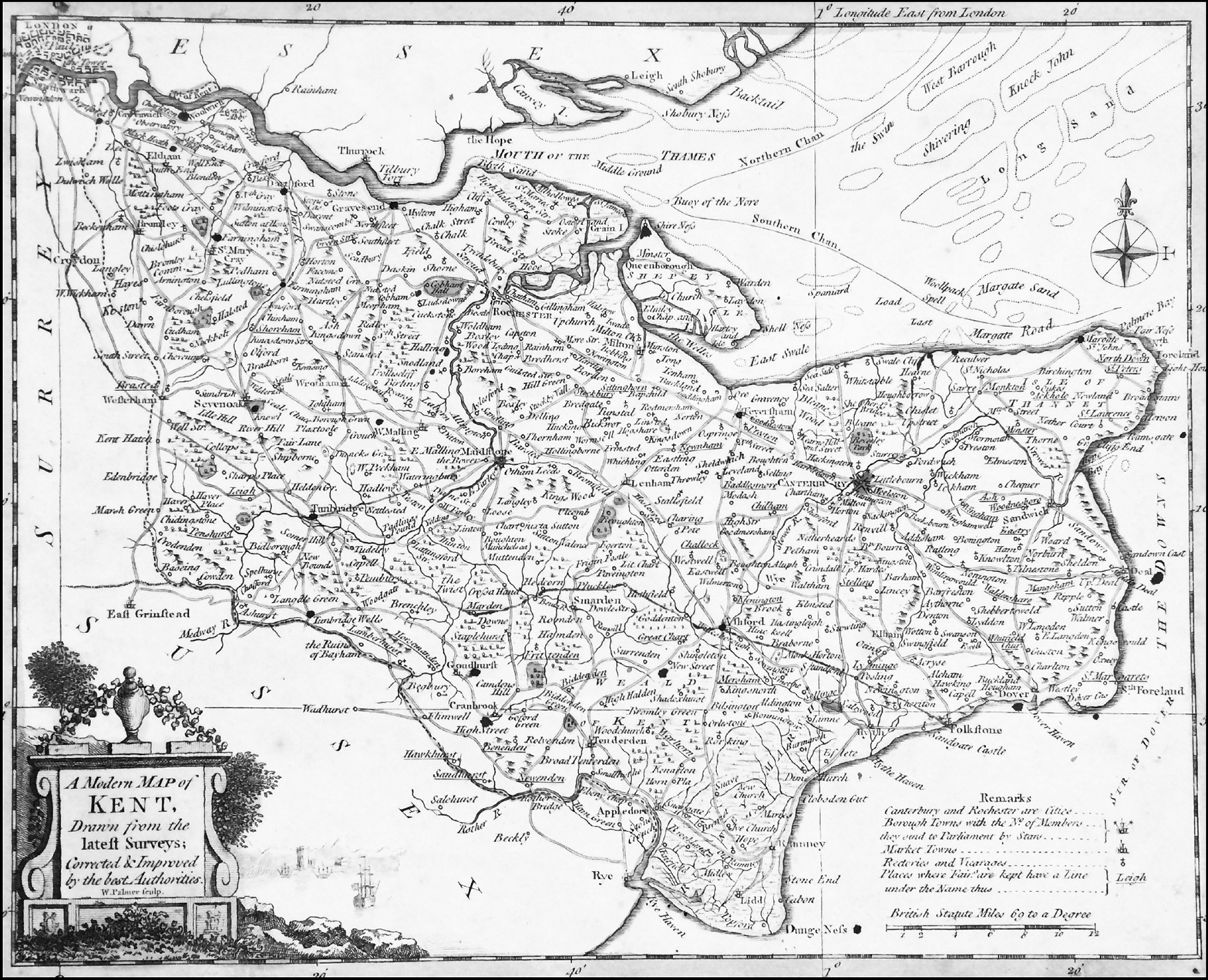

A nineteenth-century map of Kent. Traditionally if you’re born east of the River Medway you’re a ‘Man of Kent’, west of the river, you’re a ‘Kentish Man’. Happily I was born in Surrey.

The shire, or county, was further divided into ‘hundreds’, also known in some areas as wapentakes or wards. Indeed, until the introduction of districts by the Local Government Act 1894, hundreds were the only widely used descriptive unit between the parish and the county. Hundred boundaries can be logical and neatly aligned in ways you would expect, but they are often independent of both parish and county boundaries – in other words a hundred could be split between counties, or a parish could be split between hundreds. Over time, the principal functions of the hundred became the administration of law and the keeping of the peace – so there would be hundred courts held every few weeks to tackle local disputes or crimes. But the importance of hundred courts gradually declined, most powers shifting to county courts when these were formerly established in 1867.

Over the centuries there was a gradual administrative split between town and country. Henry II and other monarchs granted royal charters to many towns across England (which were thereafter referred to as boroughs). For an annual rent to the Crown, the towns earned themselves privileges such as the exemption from feudal payments, rights to hold markets and to levy certain taxes. In other words they paid for the rights to make money and have a modicum of self-government.

In the 1540s the office of Lord Lieutenant was instituted in each county, becoming the Crown’s direct representative in a county and also responsible for raising and organising the county militia. Local justices of the peace took on various administrative functions, presiding over roads and institutions and could levy local local taxes. If borough status gave towns specific rights, so wannabe cities could lobby for greater independence from the county, effectively becoming their own state, with their own set of officials, powers and quarter sessions courts.

The ecclesiastical parish is the jurisdictional unit that governs Church affairs within its boundaries, each keeping its own records. Small villages will often be part of a larger parish, the ‘headquarters’ of which are elsewhere. And a parish may consist of one or more chapelries, dependent district churches or ‘chapels of ease’ – a chapel situated closer to communities that lived a long distance from the parish church.

In contrast to an ecclesiastical parish, the civil parish is the lowest tier of local government (below districts and counties). Today a civil parish can range in size from a large town with a population of around 80,000 to a single village with fewer than a hundred inhabitants. Civil parishes in their modern sense were established by the Local Government Act 1894, when parishes were grouped into districts and each civil parish had an elected civil parish council.

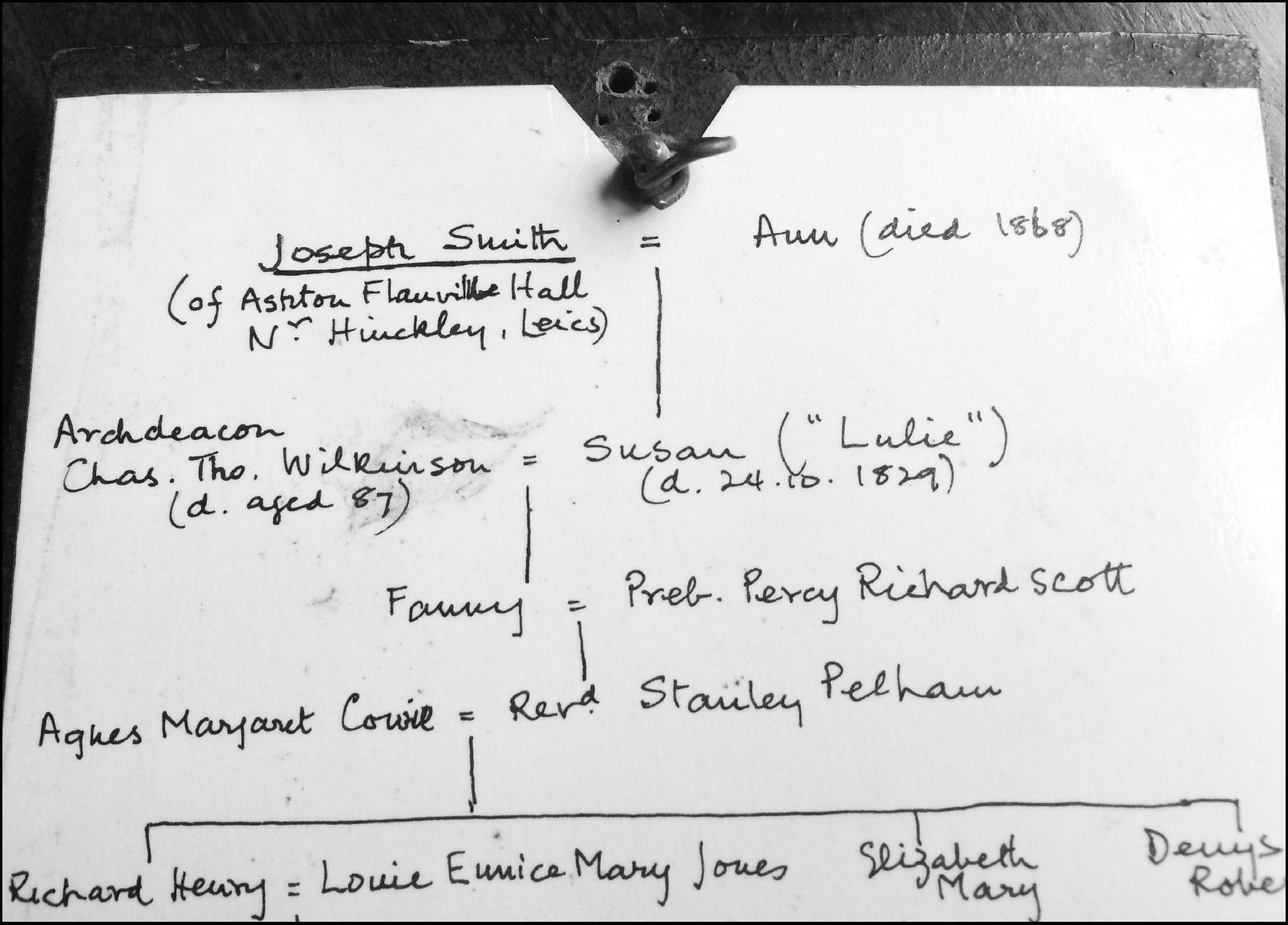

A misspelling can lead researchers down blind alleys. This portrait has a rough family tree inscribed on the reverse. However, the parish of Joseph Smith is noted as Ashton Flauville, when it should be Aston Flamville.

These divisions and boundaries cause most trouble when you actually set out to find a particular record. Let’s look at Yorkshire. Changes in 1974 transferred some North Riding parishes to County Durham, while Harrogate, Ripon and the Skipton area, all previously in the West Riding, formed part of the newly created county of North Yorkshire. Records for the part of North Yorkshire that was formerly part of the East Riding are held by the East Riding Archive Service in Beverley. Meanwhile, North Riding archives still hold records relating to the parts of the former North Riding lost to Durham and Cleveland/Teesside under the boundary changes of 1974. Therefore, a genealogist new to this particular area would need to find out whether their ancestor’s records are likely to be held at North Yorkshire County Record Office in Northallerton, Teesside Archives in Middlesbrough, Durham County Record Office or at the Borthwick Institute at York University.

There are also complications caused by ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The western portion of North Yorkshire is in the Archdeaconry of Richmond and formerly in the diocese of Chester. So wills before 1858 and Bishop’s Transcripts for that area are held at West Yorkshire Archives at Sheepscar, Leeds. The eastern side of North Yorkshire is in the Archdeaconry of Cleveland, and so early wills and the Bishop’s Transcripts are at the Borthwick Institute.

In Scotland the equivalent to the borough was the ‘burgh’, the first royal burghs dating from the twelfth-century reign of King David I. These burghs enjoyed some autonomous freedom, including rights to impose tolls and fines on traders within a region. The oldest document held at the Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives is a Charter of King William the Lion of c. 1190, which grants the Burgh of Aberdeen the right to its own merchant guild, confirming an earlier charter of his grandfather King David I. Aberdeen’s Town House Charter Room holds – among other things – the city’s charters and deeds, as well as burial registers, guildry records and the minutes of the council from 1398 to the present day – the oldest council minutes in Scotland.

The origins of Scottish counties lie in the sheriffdoms over which local sheriffs exercised jurisdiction. After the Acts of Union 1707 burghs continued to be the principal sub-division of Scotland. Then after reorganisation in 1889 local administrative units comprised counties > cities > large burghs > small burghs. Meanwhile, congregations of the Church of Scotland and other Presbyterian churches were governed and administered by the Kirk Session, which consisted of elected members and a minister.

Irish land divisions can seem equally complicated. Broadly they run as follows, province > county > barony > parish > townland.

Modern-day Ireland is split into the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Across the whole island there are four provinces, each divided into counties. The Republic of Ireland comprises the provinces of Connaught, Leinster and Munster, and three counties within the province of Ulster (Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan). Then Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK, consists of the remaining six counties of the province of Ulster (Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone).

These four provinces are the oldest sub-divisions and broadly follow ancient clan kingdoms, but no longer hold an important administrative purpose. More important is the barony. While baronies were made obsolete in 1898, they were used to describe different areas in many important genealogical sources such as land surveys. Annoyingly, these baronies often span parts of multiple civil parishes and counties.

Today counties are more important administratively, and each has a county town/city, and each is divided into civil parishes. As with the UK, there are two types of parish: ecclesiastical and civil. Finally, each civil parish is divided further into townlands (not to be confused with towns). The townland is the smallest official division, originally based on an area deemed sufficient to sustain a cow.

Ecclesiastical parishes are further complicated because there are both Church of Ireland parishes and Roman Catholic parishes, which again have different congregations and boundaries. The Irish Genealogy Toolkit offers a really good guide to this complicated situation (www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-land-divisions.html).

Finally, all over the UK and Ireland there were administrative divisions of Poor Law unions, which were established during the nineteenth century to tackle increasing poverty. We will look at these in more detail in Chapter 4, ‘Secrets, Scandals and Hard Times’.

If you’re reading this and feeling overwhelmed, please understand that is not my intention. I want to illustrate that things are complicated, but I’d also want to reassure you that there is a lot of guidance and expertise out there. Genuki (genuki.org.uk), for example, has in-depth guides to civil and ecclesiastical parish boundaries in counties across the UK and Ireland. Indeed, while it’s not the most modern website to look at, its greatest strength is its simplicity. It is a very good place to get to grips with the local administration and records of an area.

● Shire: a traditional term for a large division of land, which is why so many counties have ‘shire’ within their names.

● Ecclesiastical parish: the parish is the jurisdictional unit that governs Church affairs within its boundaries, each keeping its own records. Small villages will often be part of a larger parish, the headquarters of which are elsewhere. A parish may consist of one or more chapelries, dependent district churches or ‘chapels of ease’ – a chapel situated closer to communities that lived a long distance from the parish church.

● Chapelry: a small parochial division of a large, populated parish. Most would keep their own parish registers of baptisms and burials, and where authorisation was granted, marriages could be performed and registers kept. In particular, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire and Greater London have many parishes divided into many more chapelries. The largest parish in England is the one served by Manchester Cathedral – within its bounds there are over 150 smaller chapels.

● Diocese: parishes grouped together under the jurisdiction of a bishop. Some dioceses include one or more archdeaconries administered by an archdeacon.

● Parish records: ‘parish records’ usually means parish registers. ‘Parish chest’ records are other parish-level sources such as settlement examinations, removal orders, apprenticeship indentures and more.

● The United Kingdom Census of 1911 noted that 8,322 parishes in England and Wales were not identical for civil and ecclesiastical purposes.

● The ‘Danelaw counties’ of Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland and Lincolnshire were divided into ‘wapentakes’ instead of hundreds. ‘Danelaw’ refers to parts of England where the laws of the Danes held sway.

● Deanery: a group of parishes forming a district within an archdeaconry.

● In Wales traditional and now largely obsolete units of land division include cantref/cantred or commote.

● Electoral district: a territorial sub-division for electing local Members of Parliament. It is also known as a constituency, riding, ward, division, electoral area or electorate.

● Catholic parish boundaries are different to those of the Church of England.

Genuki: genuki.org.uk

Irish Genealogy Toolkit, Irish Land Divisions: www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-land-divisions.html

ScotlandsPeople: scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Cox, J. Charles. Parish Registers of England, Methuen, 1910

Humphery-Smith, Cecil R. The Phillimore Atlas and Index of Parish Registers, Phillimore, 2002

You cannot beat the excitement of actually visiting an archive in person and handling a document that contains a reference to, or even the handwriting of, your ancestor. To this end there is a network of national and regional archives across the UK and Ireland, many of which can boast documents stretching back to the Middle Ages. Hull’s archives include a document from 1299, while one of the oldest items held at the London Metropolitan Archives dates from 1067 – a charter from William the Conqueror sent to the city just after the Battle of Hastings, but before he entered London. It’s basically a message of reassurance, an eleventh-century ‘keep calm and carry on’, a promise, written in English, that he wasn’t about to trash the place.

There are many hundreds of archives across the British Isles. First, there are the national collections: the National Archives of Scotland, The National Archives in Kew (TNA), the British Library, the National Library of Wales, the National Library of Scotland, the National Archives of Ireland, the National Library of Ireland and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI). Next, there is a network of county level archives, and below these borough or city collections, museum collections, university special library collections, specialist libraries and local history libraries.

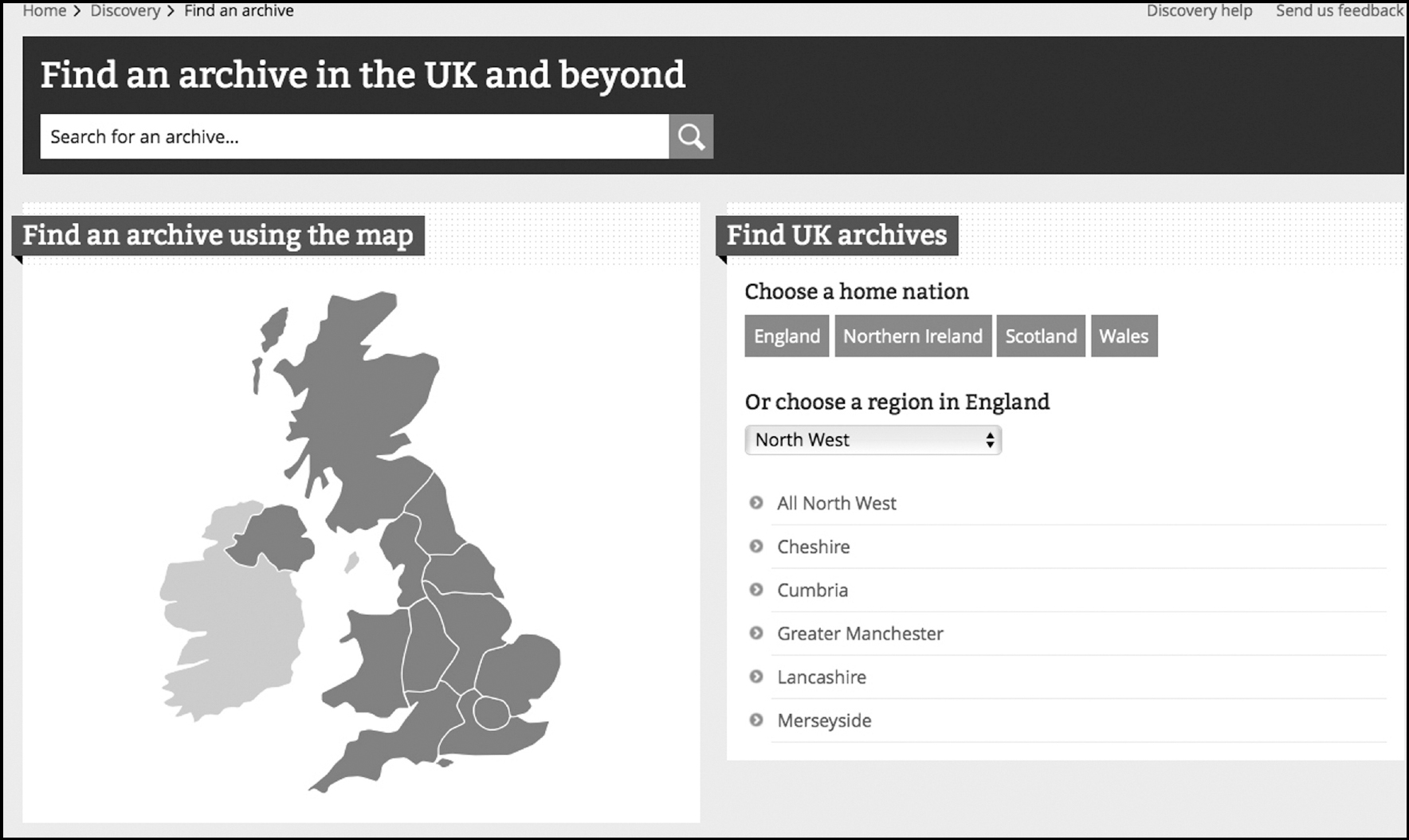

The National Archives’ ‘Find an archive’ page allows you to search for archives, museums and other repositories across the UK. Scroll down and you can also explore overseas archives by country.

Assuming you know when and where a member of the family lived, your first port of call should be the relevant county or borough archive. Thankfully, for those who cannot easily visit in person, we are living through a period of mass digitisation, meaning more and more can be achieved remotely from simple catalogue or index searches to downloading images of original documents. In this respect some counties across the UK have gone further than others. Some record office websites boast digitised sources and helpful finding aids, others are still some way behind. Some have struck longstanding agreements with the likes of Ancestry, FamilySearch, TheGenealogist and Findmypast, others have not started down this road. So, if you are researching in what appears to be something of a digital backwater, and can’t visit the archives in person, you may need to look into research services the record office or local family history society can offer, or think about hiring a professional.

Most archives’ collections include county, borough, town, parish and other local government records, parish chest material, electoral registers, tax records, photographic collections, local newspapers, records of institutions such as hospitals and schools, court material, records of individuals, families and charities. They will normally offer banks of microfilm/fiche readers and lines of computers, usually providing free online access to commercial websites such as Ancestry and sometimes to internal digital finding aids.

Alongside the ‘usual’ sources, there will be collections unique to the area – local business records, or collections relating to individuals. The Surrey History Centre in Woking, for example, has the family papers of Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, garden plans, watercolours and photographs by Gertrude Jekyll, the Robert Barclay collection of Surrey illustrations and the Philip Bradley Collection of fairground photographs. It also has the diaries of English antiquary William Bray, which features what is believed to be the earliest known manuscript reference to baseball. On the day after Easter in 1755, the then 18-year-old William wrote: ‘After Dinner Went to Miss Seale’s to play at Base Ball, with her, the 3 Miss Whiteheads, Miss Billinghurst, Miss Molly Flutter, Mr. Chandler, Mr. Ford, H. Parsons & Jolly. Drank tea and stayed till 8.’

Alongside county archives, there may be city, borough or town collections. These sometimes form part of one unified county service, or are administered separately. The ancient boundary lines of the county of Essex covered parts of what is now Greater London – namely the modern London boroughs of Newham, Redbridge, Havering, Waltham Forest, Barking and Dagenham. Today each of these maintains its own borough archive so researchers with interests here may find relevant material in both the Essex county collections and the local borough collections.

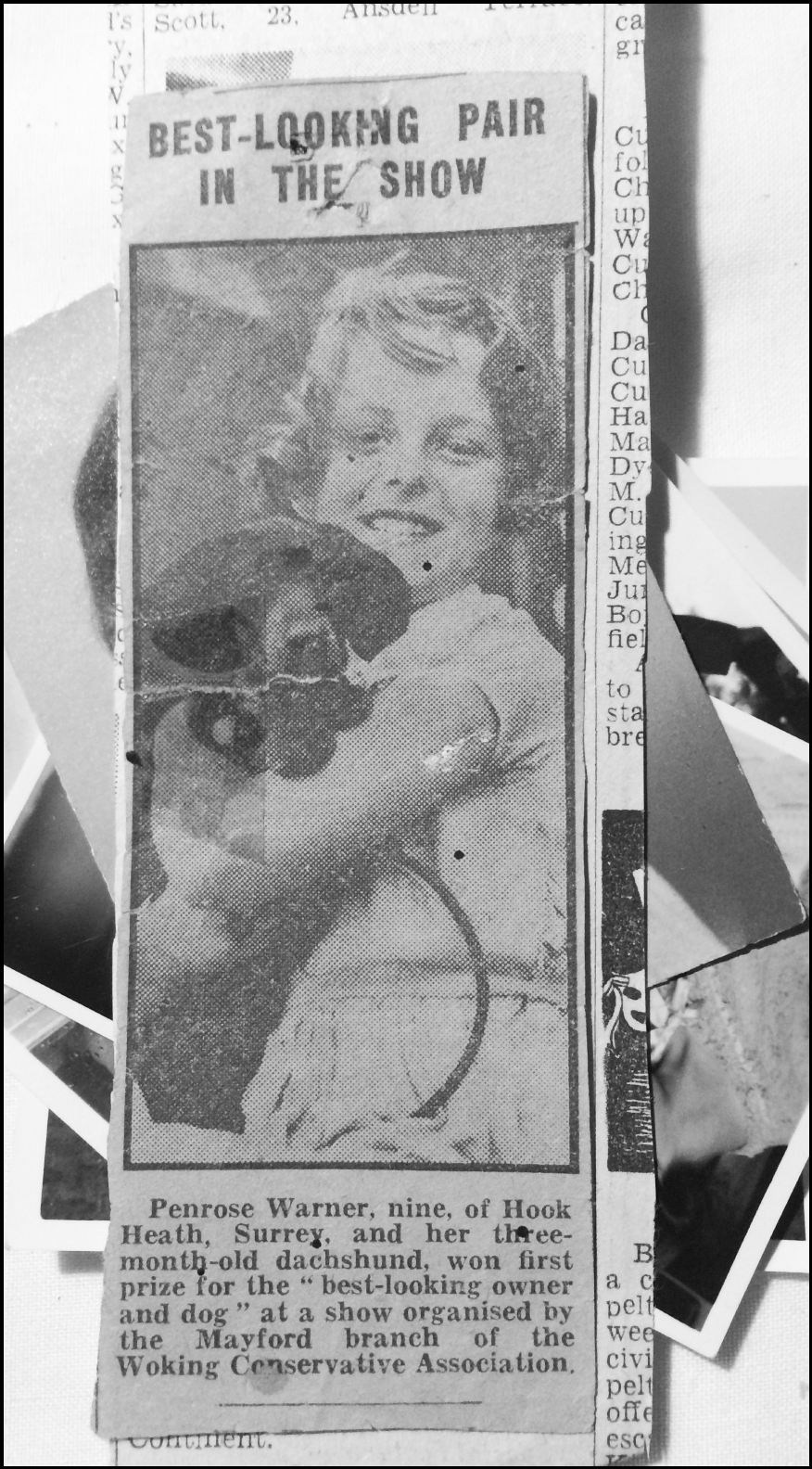

Most local history libraries maintain collections of local newspapers. When searching any source you should always have spelling variants in mind. This local newspaper story calls my mother ‘Penrose Warner’, instead of Warren. And they don’t even bother to name the dog.

Many libraries across the UK have local studies departments. These can make an excellent alternative to the county archive as a research venue as they often offer microform access to county wide collections (such as parish registers or census material), and usually offer free online access to the likes of Ancestry and Findmypast. Local studies collections can also include original manuscript collections such as newspapers, photographs, electoral registers and more.

Finally, hundreds of museums pepper the British Isles, and many maintain their own archival collections. Some will be preserved on site, others may have been deposited with the county archive. Many will have very basic websites, with little more than details of how to visit, others will have searchable catalogues, digital photo libraries, research and look-up services, digitised databases, indexes and more.

The place to start your search for an archive used to be known as Archon, but is now simply the ‘Find an archive’ service through TNA’s Discovery catalogue (discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/find-an-archive). This allows you to browse archives in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, or conduct separate searches for overseas repositories. You can search by area or by name of the archive. A search by ‘mining’ returns seven results, including the National Coal Mining Museum for England, the Mining Records Office and the Scottish Mining Museum. For archives in Ireland you can use the Irish Archives Resource (www.iar.ie), an online database that contains searchable archival descriptions.

Assuming most of your research concentrates in one area, it is likely you will quickly become familiar with the county’s archival catalogue. Most, but not all, are online. Some have their own dedicated catalogue website, others are only available through larger multi-archive catalogues such as Archives Wales or TNA’s Discovery (which has records from TNA and over 2,500 archives across the UK).

It’s important to understand how much a catalogue can reveal. An online catalogue is a searchable database of the documents and books held by the repository. These are finding aids, designed to help you find relevant documents and note down references so you can then request to view the documents in the research/reading room.

The amount of information contained within county catalogues varies a great deal – not only from archive to archive, but also from collection to collection within the same archive. Some name-rich sources popular with genealogists will often have been name indexed so they are more easily searchable. But many will not. Some searches may result in simply the name or title of an uncatalogued collection. In addition, you may find that not all collections are available for public consultation.

More sophisticated catalogues will link direct to images of the original documents and photographs. Most catalogues will include thousands of names, without necessarily functioning as a full index to all documents. So, you might be able to search the catalogue for details of the church records they hold, but you won’t be able to trawl by all the names that appear in the baptism, marriage or burial registers.

Most will give descriptions of each item including the following fields: a reference or finding number, a title and date, and some detail about the parent collection. So, you search the catalogue, find an item of interest, then use the reference or finding number to order the item in the research room – many archives have online request forms. (They may also offer copying or look-up services for remote researchers.)

The Essex Record Office catalogue Seax (seax.essexcc.gov.uk) is a good example. It boasts indexes and many free images of documents, as well as links through to ERO’s own subscription service, Essex Ancestors, where you can download images of parish registers and wills for a fee.

Online catalogues offer various advanced search options to help narrow your field. Sticking with Seax, it offers an ‘Advanced Mode’ option where you can search for different words or phrases by filling in the fields on screen. So, if wish to locate an electoral register for a certain year, you type ‘electoral register’ into one field, the name of the parish in another, then fill in the date field and click search. You can also use catalogue references to narrow searches within certain collections: type ‘Chelmsford’ in the first field and ‘SA’ in the second and it will search all references to Chelmsford within the Sound Archive.

Always be wary of narrowing your search too quickly. If you narrow by a parish that turns out later to be incorrect, you may miss the vital reference you have been searching for. Also most catalogues offer some kind of browse option, where you simply click on different categories or collections. This is often a good starting point as it is likely to reveal background information, giving each collection its historical context and explaining the kind of documents that have survived.

Some important multi-archive catalogues include: TNA, Discovery (discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk), Archives Wales (archiveswales.org.uk) and the Scottish Archive Network (scan.org.uk).

Another potential source of help and advice can be genealogy discussion groups, which often cover specific regions, time periods, surnames and more. Genuki maintains a database of mailing lists and newsgroups at (www.genuki.org.uk/indexes/MailingLists.html). There are also the vast networks of message boards (Ancestry’s are at boards.ancestry.com), which include specialised topics such as surnames and locales. At the time of writing there were 25 million posts on more than 198,000 boards. Commercial genealogical websites normally offer some kind of ‘community’ or social networking features, which allow you to get in touch with other family historians working in the same area or researching the same surname or branch of a family.

Dedicated online forums can also be an excellent platform for posing queries, or finding out more about what the wider digital community is up to in your area of research. Just reading other queries and replies from other researchers can often resolve your own problem before you even have to ask it.

Rootschat is one of the largest UK forums (rootschat.com), with thriving specialist sections and threads, including many sections aimed at beginners and an archived library of threads going back to 2003. Other general interest examples include GenForum (genforum.genealogy.com), LostCousins (forums.lc/genealogy/index.php), British Genealogy & Family History Forums (british-genealogy.com) and Family History UK Genealogy Forums (forum.familyhistory.uk.com). Specialist examples include the Family Tree DNA (forums.familytreedna.com/), the Great War Forum (1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/), the British Medal Forum (britishmedalforum.com) and the regional Birmingham History Forum (birminghamhistory.co.uk/forum/).

If you catch the genealogy bug, only to find that you simply don’t have the time or resources to invest in a dedicated research trip, it might be time to hire a professional.

Many county record offices, regimental museums and genealogical societies offer various look-up services. These can be specific to a source – such as parish material perhaps – or a more generalised research service, with a sliding scale of charges. Most also offer copying services, where for a fee they will supply digital or paper copies of specific documents or entries. This can be a convenient way of remotely accessing records that have not yet been digitised.

If you are researching from overseas and need more help, hiring an expert on the ground can save both time and money. You might choose to hire a professional for advice, or to use a particular skill or specialism, or simply to carry out the more time-consuming legwork. You might ask them to research your entire family, one branch of the family or a single individual.

Having selected a professional, you need to approach them with all the relevant details of your research – what is known and what is unproved – and then explain what you want, which questions you want answered. As with hiring a mechanic to fix your car, you need to find out if the researcher can help, what it will cost, how long it will be before they can start and when they expect to complete the project.

Many professionals charge on a basis of an hourly rate, which, according to a useful Society of Genealogists’ guide on the subject, varies from £20 to £50 per hour (‘and perhaps more or less’). The same guide urges you to bear in mind the different types of researcher – those whose work is their sole source of income, and those who see it as a secondary activity. Remember though that many researchers will not be able to give an accurate estimate of cost until they have begun, as some tasks may prove more time-consuming than expected. Most professional genealogists usually ask for money in advance and once the work is complete the resulting reports should include pedigrees, typed up transcriptions, copies and details of everything that was searched – including all the sources where nothing useful was found.

Some record office websites have lists of recommended professionals, which can be a good option as they are likely to have local expertise. Otherwise you can browse advertisements on websites and in magazines, search via genealogical forums or Twitter, or go through professional associations such as the Association of Genealogists and Researchers in Archives (www.agra.org.uk).

To find an archive:

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.u

To find a genealogical group:

Federation of Family History Societies: ffhs.org.uk

Scottish Association of Family History Societies: safhs.org.uk

Guild of One-Name Studies: one-name.org

To find a professional researcher:

The Association of Genealogists and Researchers in Archives: www.agra.org.uk

The Association of Scottish Genealogists and Researchers in Archives: www.asgra.co.uk

The Society of Genealogists: www.sog.org.uk

Includes a useful ‘hints and tips’ guide to hiring a professional.

The Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland: www.apgi.ie

Institute of Heraldic & Genealogical Studies: ihgs.ac.uk

Clarke, Tristram. Tracing Your Scottish Ancestors, Birlinn, 2012

Evans, Beryl. Tracing Your Welsh Ancestors, Pen & Sword, 2015

Grenham, John. Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, Gill & Macmillan, 2012

Waddell, Dan. Who Do You Think You Are?: The Genealogy Handbook, BBC Books, 2014