IT IS remarkable that the early civilized mind took it as self-evident that there were beings who lived forever. This is not so obvious to the modern mind; one has to dig into the depths of psychological experience to rediscover what was self-evident to our ancestors. Taken as a whole, the Greek Pantheon tells us that the immortal ones are fundamental presences. In psychological terms, we can say that they are inhabitants of the collective unconscious. They are expressions of the archetypes, those psychic entities that continue to exist unchanging while the momentary individual egos come and go.

One of the striking features of The Iliad is that gods and men are active on the same stage. In the course of the battles and the to-and-fro of the champions and the warriors and armies, not only are there human soldiers on the field, but gods are there fighting along with them. Every now and then one of the gods will take one particular warrior and imbue him with superior power, or if a favorite is having a bad time of it, he may just pick him up bodily in a cloud and transport him to safety. If we take this as a picture of the psychological realm, we see that there is a free, fluid interpenetration between ego experience and archetypal factors signified by the gods. The nature of psychological experience is that what we do and what we experience are constantly interpenetrated by these other powers, although as a rule consciousness is making so much noise, it doesn’t notice.

The fact that there are twelve Olympians is surely significant—although the roster is not absolutely fixed; there were some late revisions. Dionysus is a late addition, and Demeter is not always present. However, it seems important to point out in a general way the symbolism of the sacred number twelve. One need only think of the twelve hours of the day, the twelve tribes of Israel, the twelve apostles of Christ, the twelve signs of the zodiac, the twelve labors of Heracles. Twelve is related to the symbolism of wholeness, to the mandala and the quaternity. It is a particularly meaningful number for the sacred ones. As the ego looks in the direction of the Self, the transpersonal center of the psyche, it tends to experience the Self not as a unity (at least not at first) but as a multiplicity of archetypal factors that one can think of as the Greek gods.

Let us consider the gods as a whole before discussing the individuals. From the viewpoint of depth psychology, the gods stand for the archetypes, the basic patterns within the human psyche that exist independent of personal experience. They are the templates on which the individual life is formed. Mythologically, these eternal patterns are thought of as gods, existing in a special place apart from ordinary human experience. The Greeks called that special region Olympus, and thought of it originally as a mountain peak, and later as the whole upper sky. In The Odyssey Homer describes Olympus:

. . . Olympus, where, they say, is the abode of the gods that stands fast forever. Neither is it shaken by winds or ever wet with rain, nor does snow fall upon it, but the air is outspread clear and cloudless, and over it hovers a radiant whiteness. Therein the blessed gods are glad all their days. . . . 1

Of course, this is just one version of heaven as the transcendent realm, the realm beyond the personal. A parallel conception was the image of Yahweh in Hebrew mythology. He was also a sky god and inhabited Mount Sinai, an equivalent of Mount Olympus and analogous to the Christian heaven as well. Indeed, almost all primitive mythologies involve some notion of heaven as an abode for the gods, with something of this perfect, eternal, untarnished quality.

Psychologically we can consider the idea of an Olympian realm as a projection onto the outer world (onto the sky in this case) of an inner state. It would be a state that is eternal, unchanging, and a realm of the spirit, as opposed to matter. Every now and then one encounters the notion that such images amount to nothing more than wish fulfillment. But no wish was fulfilled in the original Greek conception of Olympus, since as the myths and all the early literature make clear, there was no advantage to them in imagining the Olympians up in their heavenly realm. Quite the contrary, the Olympian existence merely emphasized the misery of mortal life. We are left with the conclusion that there exists an eternal psyche, or something symbolized by an eternal psyche, that is of greater duration than the ego. This idea is developed in Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, the abode of the archetypes. In his purely psychological view, the heavenly realm of the Greek gods is seen as a part of the human psyche, which is beyond time and space and beyond the control of the conscious personality. The early images such as that of Olympus are understood as translations of psychological realities into external ones.

When we take the Greek gods individually, we have a complete chart of the eternal or impersonal dimension of the psyche. The assembly of the gods gives us a set of archetypal principles, along the lines that Nietzsche elaborated when he described the Dionysian and Apollonian principles in his essay “The Birth of Tragedy.” The same sort of elaboration can be made for each of the Greek gods, so that we see a Zeus principle, an Ares principle, an Aphrodite principle, an Athena principle, and so on.

We experience these principles in different ways. We observe them, for instance, lived out in the personalities and behavior of others. If we review our various friends and acquaintances we can come up with examples—not in pure culture, of course, but approximate examples—of each of the archetypal principles the Greek gods embody, and we can equally well, by self-examination, detect one or more such principles that are guiding factors in our own psychology. We will encounter expressions of them in our dreams as numinous entities, having a guiding or helping capacity of some kind. The more we approach the state of wholeness, the more likely we are to have had at least brief encounters with most, if not all, of these divine principles. Each of us contains within us the whole Olympian Pantheon.

Let us start with Zeus. He was the ultimate authority and belonged to a trinity, the paternal authority principle, which was made up of Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades. That Olympian triad can be thought of as different manifestations of the same basic principle. But Zeus is the supreme deity, and comes closest of all the members of the Pantheon to embodying the whole Self, even though he represents only the masculine side. He was a sky god, associated with wind, rain, thunder, and lightning, and was the master of spiritual phenomena, since it was the spirit realm that was signified by the sky and the manifestations of the weather. He was a carrier of justice and judgment, an embodiment of law and the punisher of transgression of the law, accomplished by the hurling of the thunderbolt. He was the personification of creative energy, which constantly spilled out and had an unceasing urge to impregnate, hence his perpetual love affairs.

It was an energy continually striving to realize new consciousness or new fruits of itself. There are long lists of the lovers of Zeus, and by and large they had an unhappy time of it. Hera, personifying the feminine embodiment of the Self, was fiercely opposed to these dalliances, and would often punish Zeus’ lovers. For example, Zeus fell in love with the beautiful Io and then turned her into a white cow so that she could escape Hera’s detection. This ruse failed and Hera set gadflies after her which, stinging, pursued her around the world. This was typical of Hera’s jealousy, and through these images we learn that when the divine creative energy flows into the human realm, there is a reaction from the gods, as if there is jealousy over what has been lost to them. It appears that every gain of the ego must be paid for by punishment for having appropriated the divine energy. This psychological fact is seen many times in the consequences of Zeus’ amours with mortal women. These affairs and Hera’s fits of jealousy were often treated as comic relief in the sagas of the gods. However, we must remember that these are archetypal dynamisms that become the fate of human individuals, and as such can be tragic rather than comic.

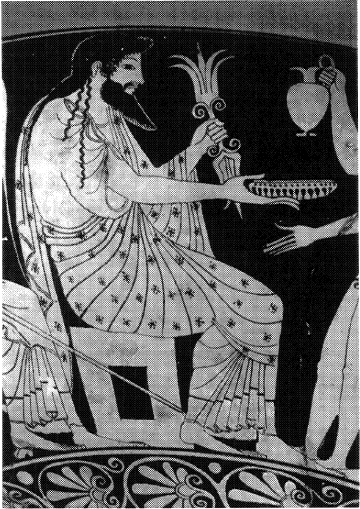

FIG. 3. Zeus holding a thunderbolt and libation cup. (Detail of an Attic cup, c. 520 BC. Museo Nazionale, Tarquinia. Photo: Nimatallah/Art Resource, New York.)

We find in the image of Zeus and his lovers early forms of the same archetypal phenomenon that appears later in the Christian Annunciation: the union of the divine and the human. The Annunciation, the meeting of Mary and the Holy Ghost, appears to be a gentler encounter, yet the ultimate fate of Christ, the fruit of that union, was anything but gentle.

In these myths, we have the strange phenomenon of Zeus and Hera apparently working at cross-purposes. Zeus has the urge to create, to generate more and more offspring by different mothers in different places, and Hera’s role is to resent and attempt to frustrate or somehow punish individuals who succumb to Zeus’ desires. It is a little like what we see in the book of Job, where Yahweh is divided against himself; the other part of him appears as Satan. Here we see a certain ambiguity in the world of the archetypes, which are not necessarily interested in the comfort and well-being of the human ego; they may be more interested in something beyond the ego’s ability to value or understand.

The imagery of Zeus can be seen to correspond closely to the first hexagram of the I Ching, called The Creative. The I Ching, the ancient Chinese oracle book, says about this hexagram, “Six unbroken lines. These unbroken lines stand for the primal power, which is light-giving, active, strong, and of the spirit. . . . Its essence is power or energy. Its image is heaven.”2 Thus we see that we are dealing here with an archetypal image that can express itself and clothe itself in multifarious ways in different cultures, but its underlying essence is the same.

How does this factor appear in psychology? It is not hard to distinguish what we might call a Zeus temperament. There are certain men—we are considering a masculine phenomenon—who are effective, self-righteous, who are embodiments of moral authority, and who are capable of casting thunderbolts at transgressors around them. They could equally well be called Yahweh temperaments, since Yahweh and Zeus are virtually interchangeable in their essential characteristics. Such a principle may also be experienced internally. If a person falls into an unconscious identification with it, he will find himself acting and reacting as though he himself were the Law, the ultimate authority. Making connection with the image objectively, rather than falling into identification with it, can lead to the capacity for objective judgment and appraisal.

An example of the Zeus phenomenon appeared in a dream of a young man who was contemplating leaving his wife and several children in order to pursue an infatuation with a young wealthy woman. Her wealth was as seductive to him as her beauty. At that point he had this dream:

I stand in the middle of the street looking up at gray, fast-moving skies. Behind the stormy facade I catch momentary glimpses of sunny, clear weather. Apparently I am deciding some sort of trip and the weather is the important factor in the decision. On my right a group of elders are gathered in discussion. I ask them, “Do you think I should leave? The sky seems clear to me.” They shake their heads collectively. I refuse the advice and I begin to walk straight toward the dark clouds. I move about two steps when the sky cracks open and a huge, brown hand reaches down, picks me up, and points me in the other direction.

There is an unusual combination of factors here, namely the weather and the sky, together with the transpersonal authority. This is precisely what the original sky god was conceived to be. He manifested himself in the weather, and that is still true today, though now we think of it as inner weather.

Zeus is the personification of law and judgment, what may be and what may not be. Those are not arbitrarily determined things, but have an objective basis in the psyche. The ego may think mistakenly that (as it was put by the antagonist in Plato’s Republic3) they have no existence beyond the will of the stronger. These mythological images of moral authority indicate that human principles of law and justice, on the contrary, arise from deep within the psyche.

Poseidon is the brother of Zeus and carries something of the same quality of authority, but he signifies authority from below rather than from above. He is the lord of the sea, and earth is also his domain in that he is the earth shaker, the generator of earthquakes and tidal waves. He is an earthy version of Zeus, or God as manifested from the psychic depths or from outer circumstance. He would be felt in the impact of concrete life events that are beyond one’s control.

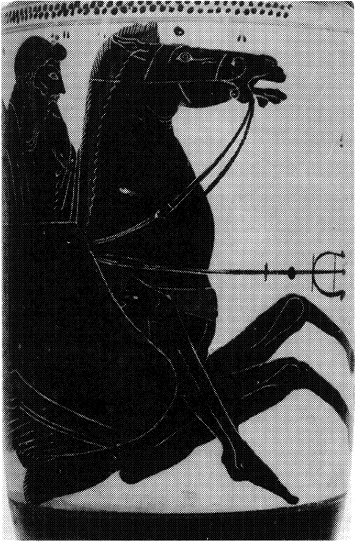

FIG. 4. Poseidon with his trident rides a hippocamp (half-horse, half-fish). (Detail of an Attic lekythos, c. 490 BC. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

In the I Ching, hexagram number 51, called The Arousing (Shock, Thunder), alludes to the Poseidon principle: “A yang line develops below two yin lines and presses upward forcibly. This movement is so violent that it arouses terror. It is symbolized by thunder, which bursts forth from the earth and by its shock causes fear and trembling.” We think of thunder as coming from above, but psychologically speaking, this Chinese image of thunder coming from below is entirely accurate. When one experiences an inner earthquake it is very much like thunder from below. The I Ching goes on to say:

The shock that comes from the manifestation of God within the depths of the earth makes man afraid, but this fear of God is good, for joy and merriment can follow upon it. . . . The superior man is always filled with reverence at the manifestation of God; he sets his life in order and searches his heart, lest it harbor any secret opposition to the will of God.4

Poseidon would be Zeus appearing from below. Dreams of tidal waves and earthquakes point to the activation of this principle—concrete events shaking one’s foundations. The Poseidon personality would have certain similarities to the Zeus personality, but his authority and effectiveness would be more apt to manifest themselves in concrete power—political and economic—as opposed to intellectual or spiritual power.

There is less to say about Hades, the third member of this trinity. Almost the only myth that refers to him is the Demeter-Persephone story, which establishes him as an abductor to the realm of the dead. So he shares with Hermes, to some extent, the position of leader into the unconscious, the Underworld. In later imagery he actually becomes a personification of death, coming to claim his victims. Another later name, Pluto, associates him with riches, so he has an ambiguous quality. It is difficult to identify a Hades personality, although a patient whose father was a mortician once described how as a little boy, when he saw the dead bodies come into his father’s mortuary, he believed his father had killed them—a graphic example of the projection of the Hades figure onto the father. Certainly in inner terms Hades, who sometimes was equated with Dionysus, was thought of as the lord of the nekyia, the journey to the Underworld, and hence he was thought of as the ruler of the phenomenon of death and rebirth, precisely the function he served in the Demeter-Persephone story.

FIG. 5. Hades holding an overflowing cornucopia, suggesting the wealth that comes out of the ground. (Detail from an Attic hydria. Copyright British Museum, London.)

Apollo’s attributes are the sun, light, clarity, truth. He represents the principle of rational consciousness which, in so many positive and heroic figures, has difficulty in being born. Hera in her jealousy pursued Apollo’s mother, Leto, so that no place on earth could be found for his birth. Finally he was born on the floating island of Delos, which shows us in what tenuous ways the light of consciousness first comes into the world. No sooner did Apollo appear than the island took root, so to speak, and became solid land. That must say something about how the divine can come into being in the human realm. No firmly established ego will grant it refuge. It is allowed in where there is a more tenuous consciousness, a floating existence, which then strikes roots and becomes permanently established. One might think of certain artistic personalities as examples of this.

Apollo killed the Python of Delphi and took over that oracle, so he is a vanquisher of unconscious terrors. He is golden-haired like the sun; he is an archer who shoots arrows of insight and/or death; he is a god of music and the lyre. Healing belongs to his realm: he was the father of Asclepius, the god of medicine. The Muses are part of his retinue, so that music, history, drama, poetry, dance, all belong to him. The Muses are those we call on when we evoke creative imagination to give us helpful images.

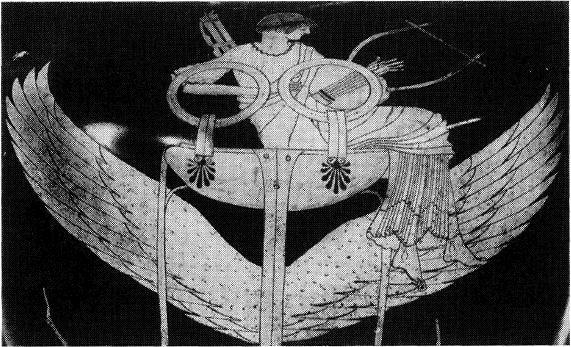

FIG. 6. Apollo, seated on a winged tripod, travels over the sea. (Detail of an Attic hydria, c. 480 BC. Vatican Museum, Rome. Photo: Alinari/Art Resource, New York.)

He has his ominous aspects, too. Marsyas, who dared to challenge him to a music contest, was flayed after he lost, signifying the stripping power of light. His arrows can symbolize the rays of the sun that bring light and insight but they also can bring death. The Iliad begins with a terrible pestilence that Apollo brought down upon the Greeks because they dishonored one of his priests. Apollo’s arrows of death struck again when Queen Niobe, who was excessively proud of her seven sons and seven daughters, disparaged Apollo’s mother, Leto, for having only two children. Her rash boasting brought down the wrath of Apollo and his sister, Artemis, who shot Niobe’s children one by one until only a boy and a girl were left. Apollo’s powerful light could be threatening in itself. He loved the nymph Daphne, but when he pursued her, she fled in terror and turned into a laurel tree to escape his embrace. In his “Hymn of Apollo,” Shelley expresses the Apollonian principle well:

The sunbeams are my shafts, with which I kill

Deceit, that loves the night and fears the day:

All men, who do or even imagine ill

Fly me, and from the glory of my ray

Good minds and open actions take new might,

Until diminished by the reign of Night. . . .

I am the eye with which the Universe

Beholds itself and knows itself divine;

All harmony of instrument or verse,

All prophecy, all medicine is mine,

All light of art or nature;—to my song,

Victory and praise in its own right belong.5

Shelley’s hymn celebrates the power and virtue of consciousness and the capacity for truth, and the Apollonian personality would be someone who emphasized these qualities, more or less at the expense of the dark, Dionysian side. In inner experience, dreams that emphasize light, illumination, fair-haired youths, would also refer to the principle of Apollo.

Hermes is generally portrayed with wings on his head and winged sandals, and with a wand (the kerykeion, which later developed into the caduceus). He is the divine messenger and hence implies something similar to what is symbolized by angels. He is a wind god and he moves with the wind. He is the god of revelation, the bringer of dreams, the guide of the dark way, and the psychopomp. He led souls to the Underworld, including Orpheus when he sought Eurydice. He was also depicted as a good shepherd, caring for the sheep, the souls of men. The later image of Christ as the good shepherd derived from this original image of Hermes. According to Aristophanes, he was the friendliest of the gods to men.

In ancient Greece he was the god of boundaries. It is generally agreed that the name Hermes is derived from the word herm, the name for a pile of stones marking a boundary. But as often happens, the god of something is the one who is greater than that thing, the one who transcends it. So, though Hermes is a guarantor of boundaries in the human realm, he is the one who is beyond them. Hermes is the great trespasser, a crosser of boundaries, the god of travelers and the patron saint of merchants, the principal travelers in early days. On the darker side, he was also the patron saint of thieves—on the first day after his birth he stole Apollo’s cattle. The boundary between what is mine and what is yours is one that he crosses. The Hermetic principle can deceive the Apollonian principle: Hermes does not always need to be truthful. He can be ambiguous and false and cunning, and that gets him into places that absolute light and truth and clarity could never enter.

FIG. 7. Hermes, running, wears winged boots and carries his herald’s staff. (Interior of an Attic cup, 520–510 BC. Private collection. Photo: Christies, London.)

He is a magician with a magic wand, and his ability to cross boundaries makes him a mediator between the human and the divine realm, or in psychological terms, between the personal psyche and the unconscious. He is a helper of heroes, a guide to secret regions; some of his functions are those indicated by his name—hermeneutics, for instance, which is the science of the interpretation of the scriptures, extracting the hidden meaning. We can think of him as the patron deity of depth psychology, because depth psychology tries to relate consciousness to the unconscious depths and so repeatedly crosses the boundary between them, thus assuming the functions of Hermes.

There is always an uncanny quality about Hermes. The ancients used to say, when silence fell on a group, that Hermes had come in, as though another dimension had been tapped. We can consider him, in modern terms, as the maker of synchronicity, the bringer of unexpected coincidences, windfalls that cannot be rationally explained.

There are people who are Hermes personalities, whose guiding direction seems to be an interest in the hidden, who are carriers of secret lore, of things that are not on the surface. They tend to be expositors of the symbolical and the dark, transcenders of the ordinary boundaries of human understanding. If a person falls into an identification with the Hermetic principle, he might be compulsively obliged to convey meaning or point out hidden references, making a nuisance of himself in the process. This would be a negative identification with the principle. As the principle is encountered internally, it can serve as an objective inner guide to the unconscious. A good example was Virgil’s function in The Divine Comedy. Virgil was Dante’s Hermes, his psychopomp to the Underworld. One encounters dream figures that allude to the Hermes principle, generally winged beings who are associated with the wind and are carriers of a mediating spirit, who have one foot in each world, so to speak, and therefore can serve as guides between the two realms.

Ares was the god of war, strife, fighting. His sister Eris was the goddess of discord. Whenever she arrived on the scene, disharmony was generated, and she was the one who threw the golden apple of discord that led to the Trojan war. Ares is the principle of aggressive energy. He appears in the myths primarily as Aphrodite’s lover, which shows us that the Aphrodite principle and the Ares principle have some connection. When Hephaestus, Aphrodite’s cuckolded husband, heard what was going on between her and Ares, he devised a net in which he caught the lovers in the act. This might tell us that a certain kind of psychological craftsmanship can capture the raw energies of aggression and lust and bring them up to the light of consciousness.

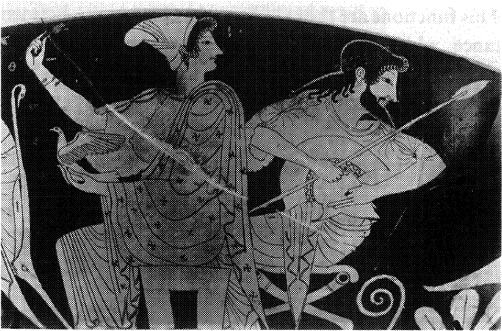

FIG. 8. Ares, bearing the warrior’s spear and helmet, sits with his lover, Aphrodite, who holds a dove. (Detail of an Attic cup, c. 520 BC. Museo Nazionale, Tarquinia. Photo: Soprintendenza Archaeologica per l’Etruria Meridionale.)

Psychological manifestations of the Ares principle would be aggression and disputation, the kind of combativeness that is enjoyed for its own sake. It is the pugilistic attitude, the attitude of the polemicist who has more interest in the fight than in substance. It also embodies courage and the capacity for aggressive self-assertion. Professional athletes, trial lawyers, and professional soldiers would fall into this category. General George C. Patton is an outstanding example. In the movie Patton, which depicted his life, Patton is revealed as possessing an almost reverential attitude toward the art of war, a true worshipper at the shrine of Ares.

As an inner experience, the Ares principle emerges in situations where aggressive energy is required. Heraclitus said that war is the father of all things,6 and in a certain sense the willingness to fight one’s way out of original containment or out of original collective identity is a requirement for psychological development. An example of this principle was the dream of a man struggling with how to approach a difficult problem in life. In the dream, a voice told him, “It will be settled on the field of Mars.” That made him realize that he had to fight. It is interesting that the dream put the advice in an antique format, “the field of Mars,” thus pointing out that his conflict had an archetypal dimension. This gave the advice to fight a dignity that it would not have had otherwise.

The Homeric “Hymn to Ares” was written probably around the eighth century BC, and it is unusual in showing Ares being petitioned for his opposite. This is the entire hymn:

Ares, superior force,

Ares, chariot rider,

Ares wears gold helmet,

Ares has mighty heart,

Ares, shield-bearer,

Ares, guardian of city,

Ares has armor of bronze,

Ares has powerful arms,

Ares never gets tired,

Ares, hard with spear,

Ares, rampart of Olympos,

Ares, father of Victory

who herself delights in war,

Ares, helper of Justice,

Ares overcomes other side,

Ares leader of most just men,

Ares carries staff of manhood,

Ares turns his fiery bright cycle

among the Seven-signed tracks

of the aether, where flaming chargers

bear him forever

over the third orbit!

Hear me,

helper of mankind,

dispenser of youth’s sweet courage,

beam down from up there

your gentle light

on our lives,

and your martial power,

so that I can shake off

cruel cowardice

from my head,

and diminish that deceptive rush

of my spirit, and restrain

that shrill voice in my heart

that provokes me

to enter the chilling din of battle.

Ares is being asked to relieve the petitioner from falling into identification with the god because he does not want to rush wildly into battle. He goes on to say:

You, happy god,

give me courage,

let me linger

in the safe laws of peace,

and thus escape

from battles with enemies

and the fate of a violent death.7

It is astonishing that in the eighth century BC Ares should be prayed to as a bringer of peace, but it is archetypally sound. Unless we have relation to the principle, we will fall victim to its negative manifestation. If we are not willing to fight when required, if we cannot summon up aggressive energy when it is appropriate, we will succumb to it in some other way. We will fall victim to someone else’s aggression or to our own autonomous assertive energy that can destroy by emerging at an inappropriate time. For example, a patient who possessed that trait repeatedly got into altercations with policemen, instead of applying his aggression to such areas of his life as dealing with his dependency, which might lead to his becoming more effective as a person. He would have done well to pray to Ares to release him, so that he could diminish that “deceptive rush of my spirit and restrain that shrill voice in my heart that provokes me to enter the chilling din of battle.”

Hephaestus, the blacksmith of the gods, was the master of fire and its operations—a metallurgist, a craftsman. He was the son of a single parent, as was Athena, and he was rejected at birth by his mother, Hera, because of his ugliness and lameness, and was thrown out of heaven, down to earth. A certain analogy exists between the fate of Hephaestus and that of Lucifer, which we can see in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

FIG. 9. Hephaestus the artisan presents Thetis with the armor he has made for her son, Achilles. (Detail of an Attic cup, c. 480 BC. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—Preussicher Kulturbesitz.)

Hephaestus is the only god who has a major relation to earth, which became his realm, and he thus signifies the divine power that has descended to earth and has become connected with earthly reality. In him we have a foreshadowing of the Incarnation image, of god becoming human. Hephaestus is a worker in concrete reality, since he is earthbound, and stands for the archetypal factor that operates within the personal and concrete. He is an inventor of useful, cunning, and beautiful devices, and a creative artist.

Hephaestus’ companions were Cabiri—the dactyls, the mysterious chthonic dwarf gods who were linked both to creativity and deformity. Hephaestus represents creativity that develops out of defect or out of need; he is the only manifestation of imperfection in this whole Olympian realm of perfect beings. That makes him particularly precious, at least to man, since it gives imperfect man a partner in the divine realm, a partner related to creativity. Psychologically this indicates that an archetypal power has entered into personal reality and has brought the creative principle to the earthly realm. It suggests that creativity is born out of a sense of defectiveness or inadequacy that requires extraordinary effort as a consequence. “Necessity is the mother of invention” is a Hephaestian principle. Although he was married to Aphrodite, she had a love affair with Ares, so Hephaestus is the archetypal cuckold. He might even be considered to stand for the creative aspect of impotence.

The Hephaestian principle, as it has developed, breaks into two streams: on the one hand into the artist and craftsman, the artistic principle emphasizing beauty, and on the other, into the engineer and mechanic, emphasizing utility. For a while at least, the alchemists combined the Hermetic principle and the Hephaestian principle because they were dealing simultaneously with symbolic, philosophic matters, the Hermetic aspect, and, as they labored over their fires, with concrete material, the Hephaestian aspect. This broke apart in the seventeenth century and the Hephaestian aspect went its own way in science and technology. Only now is the Hermetic aspect starting to reemerge in depth psychology, which does not confine itself to the Hermetic principle, but is a new combination of the two. Depth psychology is not just an abstract theoretical doctrine, but a practical operation that has its Hephaestian component in the process of psychotherapy.

The Hephaestian temperament is to be found particularly in artists and craftsmen, in those who live by beauty and those who live by utility—mechanics and makers of all kinds. Such a temperament is preoccupied with work of the hands, with earthy, concrete manifestations: occupational therapy, practical, empirical functioning, and craftsmanship of every sort.

As we look over the masculine side of the Pantheon, setting aside Zeus and his brothers, we can see Apollo, Hermes, Ares, and Hephaestus as four principles of masculine psychological functioning. We can imagine them as they operated in that immense project of the 1960s that sent a man to the moon. It was Apollonian man, represented by the scientists and the planners and their ideas, who made that leap possible, while Hephaestian man, signified by the engineers and the factory workers, made the equipment and the hardware that brought success. Arean man, represented by the astronauts, had the courage and the aggressive energy to make the trip, and Hermetic man, in those who are yet to come, will grasp the larger, hidden, and symbolic meaning of the arrival of man on the moon.