FIRST AMONG the female deities on Olympus was Hera, queen of heaven, the wife and equal of Zeus. She was the embodiment of the feminine aspect of the Self, the goddess of wifehood, motherhood, and the rights and power of women.

The myths about Hera that have come down to us focus primarily on her as an outraged spouse. Presumably this reflects the fact that the Greek myths were a product of the masculine psyche, and all the goddesses are seen through that lens. Despite this patriarchal distortion, however, it remains clear that basically as much power and effectiveness adhere to the feminine principle as to the masculine. Zeus has to take Hera into account. Beyond her fury at Zeus’ persistent affairs, Hera would also nurse long-term resentments toward certain of the human heroes: for instance Heracles and Aeneas. Yet her harassing and plaguing had the effect of goading these heroes on to greater accomplishment. Although the myth expresses the theme in negative terms, the net result is development.

The picture of marital quarreling between Zeus and Hera, which eventually became a scandal to the more sophisticated Greeks, depicts symbolically the conflict between the masculine and feminine principles; further, it shows clearly that the masculine principle is not omnipotent; it can be effectively challenged by its opposite, which is represented in the myths by the queenly figure of Hera.

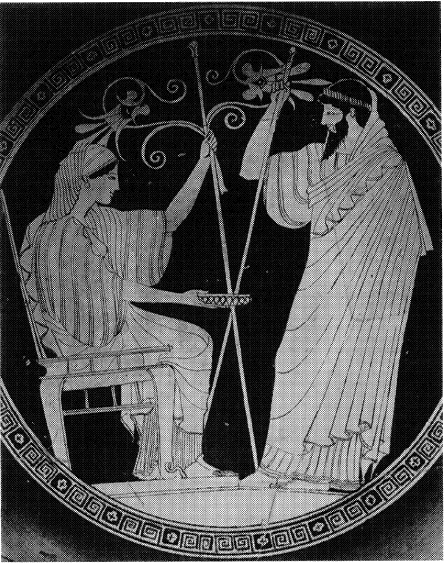

FIG. 10. Hera with Prometheus. (Detail of an Attic cylix, c. 450 BC. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. Photo: Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.)

As a type, the Hera woman has a regal, aristocratic, born-to-command quality. She is one who can be a generous patroness, and she always assumes the right to be in charge—the grande dame. To encounter the Hera principle internally means to make contact with the inner feminine as an authority to be served, which, for a woman, would be her core experience. In a man’s psychology, Hera can represent the authoritarian aspect of the mother complex, against which the masculine ego must establish itself. In more developed men, meeting Hera would mean experiencing the feminine principle as something to be served as distinct from the masculine logos principle. The Hera principle embodies the idea of the power and the authority of the feminine requiring one’s respect and, in some circumstances, worship.

Hestia is the goddess of the sacred hearth, both of the home and of the nation. She drew far more attention in Roman culture than in Greek, the Romans calling her Vesta. She personified the glowing fire on the family hearth, the natural center of the family and of gatherings of family or clan. This domestic hearth was also a sacrificial altar and Hestia was mentioned first and last in every sacrificial ceremony. She signifies the sacredness of being centered, rooted, and contained in a collective group and in a particular region, a local soil. In Rome a great cult was served by Vestal Virgins, who fed an eternal flame honoring sacred loyalty to family, tribe, city, and nation.

The geographical place that nurtures individuals, especially in their first years, tends to remain numinous throughout their lives. This can be seen as the source of patriotism, flag worship, and the nostalgia always attaching to the place one came from, to “home.” Hestia represents that. In many analyses that penetrate at all deeply, one encounters some evidence of what could be called the “geographical soul,” an aspect of the psyche that has been determined by the geography out of which one was born. Often with the descendants of immigrants, who have only a generation or two of residence in this country, this soul is to be found in the country from which their parents and grandparents came. But also one finds quite recognizable geographical souls of various kinds within the United States—a certain Southern soul, a Midwestern soul, a New England soul. They have been determined by native locality. All of this belongs to the realm of Hestia. It is not possible to worship at the hearth of the human family—that is, the cosmopolitan whole—until one has first worshiped, and still worships, at the hearth of one’s more particular locality. For the larger and more comprehensive viewpoint to be authentic, it must be based on a solid relation to one’s particular origins; otherwise, cosmopolitanism can be nothing more than alienation.

FIG. 11. Hestia, (Detail of an Attic cup, c. 520 BC. Museo Nazionale, Tarquinia. Photo: Soprintendenza Archeologica per Etruria Meridionale.)

On a certain building in New Haven, Connecticut, a plaque reads “For God, for country and for Yale.” That is an inscription to Hestia in her different manifestations, her different hearths at which one has to serve.

Demeter was the earth mother, the embodiment of agriculture and specifically of grain. An entire myth and cult associated with her grew into the Eleusinian mysteries, which will be considered later. She is the embodiment of the nourishing mother, an archetypal image well known to psychotherapists. In clinical practice, the nourishing mother is a double image. It implies a mother giving nourishment and an infant receiving it, and it is easy for that dynamic to shift so that the nourishing mother becomes a devouring mother, the process of being fed shifting from the infant to the mother. Any woman who is powerfully identified with Demeter and has a compulsive need to nourish, turns into a devouring mother. If she insists on feeding and caretaking, whether it is needed or not, the offspring remains infantile and its potential for growth is injured. The mother who must herself be fed by her children’s dependence on her, devours them. This gives rise to the image of the devouring jaws of the negative mother.

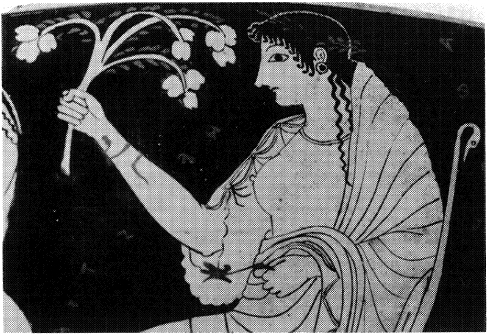

FIG. 12. Demeter, holding a torch and grain stalks, sends Triptolemus forth in a chariot drawn by winged snakes to teach agriculture to mankind. (Detail of an Attic skyphos, c. 480 BC. Copyright British Museum, London.)

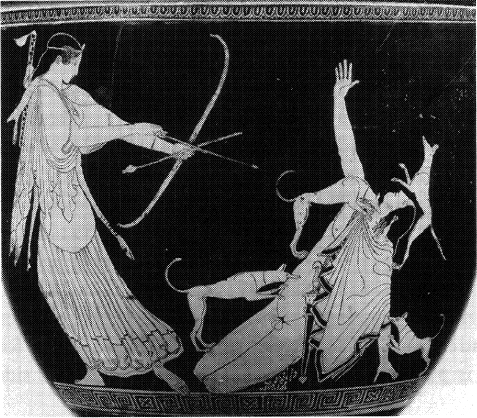

Artemis, Diana to the Romans, was associated with the moon and was the sister of Apollo, the sun. She was the goddess of the forest and the hunt, an archeress who carried a silver bow. She was virginal and brought health and well-being to virginal maidens, and was the goddess who watched over childbirth; but she was cold, chaste, and quick to be offended by men. She was the lady of the beasts, valuing wild nature more than human feelings and relationships. One of the classic stories tells of Actaeon’s encounter with her in the forest. He watched her while she was bathing, for which she turned him into a stag. He was then torn apart by his dogs, an image suggesting that Actaeon ran afoul of his own instincts. His ego was not up to such a numinous encounter with deity. It is always a dangerous thing to stumble over such transpersonal energies unexpectedly, when the ego is unprepared.

FIG. 13. Artemis threatens Actaeon, who is set upon by his own dogs. (Attic krater, c. 460 BC. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. James Fund and by special contribution.)

Another side of Artemis’ nature is shown in her relationship with Orion. Her brother, Apollo, was jealous of Artemis’ love for Orion, a great hunter. When Orion was swimming far out in the ocean one day, Apollo said to Artemis, challenging her competitiveness, “Can you hit that speck in the ocean with your bow and arrow?” She aimed with great care and hit it with her arrow, and the speck was Orion. This pictures how relationships can be destroyed in the Artemis woman through the jealousy of the spiritual animus, here signified by Apollo. It is as if the woman already has a partner within her own psyche, which wants no competitors from the human realm.

The Artemis woman tends to be efficient, self-sufficient, and not amenable to personal intimacy. As an inner experience, the Artemis principle appears as an attitude that is coldly factual and impersonal and can be as aloof and indifferent as nature. It will be experienced as cruel because it is indifferent to personal human feelings and harsh toward weakness and regressive tendencies. The Artemis woman is devoid of sentimentality in contrast to Demeter, who tends to be sentimental and protective. One might say that Artemis believes in survival of the fittest, and in men we might call her the natural anima. She has no compunctions about being cruel to weakness, but is helpful to strength, and so is growth-promoting to those for whom growth is possible; she will be hated by the regressive side of humanity.

Aphrodite was the goddess of love and beauty. Her son was Eros, who aroused passion by shooting his victims with arrows. The three Graces are associated with Aphrodite, whose qualities are grace, charm, seductive desire, and the power of the pleasure principle. Despite these attractions, the myths suggest that there are many hazards in her realm. Adonis, her young lover, was killed by a boar one day while he was hunting. In some versions of the myth, this boar was actually Ares, who was also Aphrodite’s lover and attacked Adonis out of jealousy. The story suggests that one must be in good relation with the Ares principle of aggression if one is to have an encounter with Aphrodite.

While entanglement with Aphrodite can lead to danger, to scorn her can be disastrous also. We see this in the myth of Hippolytus, who was a devotee of Artemis and so valued chastity above all, refusing the call of love. In retaliation for this slight, Aphrodite cast a spell over his stepmother Phaedra, causing her to fall passionately in love with him. Phaedra made advances to him and then, when he rejected her, told her husband, Theseus, that Hippolytus had sexually molested her (it is similar to the biblical story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife). Theseus prayed to Poseidon for revenge and as a punishment, Hippolytus was dragged to death by his horses; a bull sent by the sea god frightened them. As can be seen in this myth, Aphrodite takes her vengeance against anyone who has rejected her by involving him in some questionable or even perverse erotic situation. While it can be perilous to disregard Aphrodite, it can be equally risky to choose her over other goddesses, which is what Paris did. He was given the task of choosing the most beautiful among Aphrodite, Athena, and Hera, and he chose Aphrodite, which led to the Trojan War. All this shows that there is no easy way through the process of psychological development.

FIG. 14. Aphrodite and Pan play at dice. (Detail of an incised bronze mirror, c. 375 BC. Copyright British Museum, London.)

There are other issues here, disquieting ones. The gods and the goddesses are often in opposition. As long as the archetypal powers themselves are divided, the ego is cast in a tragic role, being split by the conflict that exists in the divine realm. As long as there is a multiplicity of principles that has not achieved a decisive unity, life is essentially tragic. It is only with the unification symbolized by monotheism and psychologically represented by the Self that there is a chance to overcome this essential tragedy.

Another hazard encountered by a number of women in mythology was brought about by equating their beauty with Aphrodite’s. Some dreadful fate always befell such women for their hybris—their consuming pride. This has the clear psychological meaning that beauty and its capacity to engender desire must not be identified with but must be recognized as a divine dynamism. To presume that it belongs to oneself is to identify with Aprodite or to challenge her divine principality. On the other hand, a more appealing aspect of Aphrodite’s power is revealed in the myth of Pygmalion. He was a sculptor who fell in love with his ivory statue of a woman and prayed to Aphrodite to bring the statue to life. She granted him his prayer, turning ivory into flesh, indicating that Aphrodite is also a life-producing principle. This story is a beautiful representation of what can happen to the imagery of the inner world if one pours enough energy into it: with the help of Aphrodite it can come to life.

At times Aphrodite is conceived as the basic cosmogonic principle, the very source of life itself. This attitude is illustrated by the opening lines of Lucretius’ poem Of the Nature of Things. He dedicates his whole poem to Aphrodite—or Venus, as the Romans knew her—and invokes her in these lines:

Mother of Rome, delight of Gods and men,

Dear Venus that beneath the gliding stars

Makest to teem the many-voyaged main

And fruitful lands—for all of living things

Through thee alone are evermore conceived,

Through thee are risen to visit the great sun—

Before thee, Goddess, and thy coming on,

Flee stormy wind and massy cloud away,

For thee the daedal Earth bears scented flowers,

For thee the waters of the unvexed deep

Smile, and the hollows of the serene sky

Glow with diffused radiance for thee!

For soon as comes the springtime face of day,

And procreant gales blow from the West unbarred,

First fowls of air, smit to the heart by thee,

Foretoken thy approach, O thou Divine,

And leap the wild herds round the happy fields

Or swim the bounding torrents. Thus amain,

Seized with the spell, all creatures follow thee

Whithersoever thou walkest forth to lead,

And thence through seas and mountains and swift streams,

Through leafy homes of birds and greening plains,

Kindling the lure of love in every breast,

Thou bringest the eternal generations forth,

Kind after kind. And since ’tis thou alone

Guidest the Cosmos, and without thee naught

Is risen to reach the shining shores of light,

Nor aught of joyful or of lovely born,

Thee do I crave co-partner in that verse

Which I presume on Nature to compose. . . . 1

When we read these lines, we see that the symbolism of Aphrodite overlaps with that of the Holy Ghost, even though one might imagine them to be quite separate. They share, for instance, the symbol of the dove, and as Jung has demonstrated in his Mysterium Coniunctionis, especially in the symbolism of what the alchemists called “blessed greenness,” we encounter Aphrodite and her life-giving capacities on the one hand, and on the other, the spiritually conceiving power of the Holy Ghost, which was thought of as the color green and can be equated with the vegetation spirit belonging to the life principle of Aphrodite.

One should also note the lines about Aphrodite from Euripides’ drama Hippolytus; they tell us how the ancients regarded Aphrodite:

Though the loved Queen’s onset in her might is more than men can bear, yet does she gently visit yielding hearts, and only when she finds a proud, unnatural spirit doth she take and mock it past belief. Her path is in the sky, and mid the ocean’s surge she rides; from her all nature springs; she sows the seeds of love, inspires the warm desire to which we sons of earth all owe our being.2

The Aphrodite woman of the present is a well-known type. She functions through the qualities of charm, appeal, and the ability and willingness to give pleasure and to convey subtle, flattering attention. Of course, as with all the other principles, the individual can fall victim to the Aphrodite function. If she identifies with it, it is as though the archetypal function lives through her and she becomes its helpless servant. We can say that just as the independent Artemis woman could be balanced by some measure of Aphrodite’s warmth, so some relation to Artemis would lead the Aphrodite woman to greater self-sufficiency.

The subjective or inner component of Aphrodite can be seen in an introverted or an extraverted way. Internally, it could mean the ability to relate to the beautiful, since beauty is an important characteristic of the Aphrodite function. Externally it would encompass the whole principle of Eros, the willingness to connect with and to be considerate of the other. This ability to make a life-enhancing connection with another is linked with Aphrodite’s whole capacity for engendering and enlarging life.

Athena was the chief deity of Athens, and a huge statue of her stood in the Parthenon. We might say that Athena stands as the goddess of Western civilization, since it originated in her city. She was born out of the forehead of Zeus, without a mother. According to the story, Zeus swallowed her mother, Metis, before Athena’s birth and then brought her forth himself through the forehead. Like Hephaestus, she is a one-parent figure; in her case this signifies a feminine content that is oriented toward the masculine and particularly helpful to it.

FIG. 15. Athena with spear and shield bearing the image of Medusa. (Detail of an Attic amphora, c. 480 BC. Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig.)

She is the principle that brings about civilization. She was thought of as introducing the plow and the olive tree, which were looked upon as the origins of civilized life. She appeared helmeted and was considered a warrior goddess, but in terms of strategy rather than of violence. She was a bringer of practical knowledge, and as her image developed, it took on more and more the explicit qualities of wisdom. She was a protector of heroes and brought wise counsel and victory to them. The outstanding example was Perseus, to whom she supplied the mirror shield that is discussed below. She has many parallels to the Jewish wisdom figure, not the least of which is the fact that she was Zeus’ favorite child. The parallel is exemplified in a few verses from the Biblical book of Proverbs in which the feminine personification of wisdom speaks of herself as Yahweh’s favorite child. In the eighth chapter of Proverbs we read:

The Lord created me the beginning of his works,

before all else that he made, long ago.

Alone, I was fashioned in times long past,

at the beginning, long before earth itself.

When there was yet no ocean I was born,

no springs brimming with water.

Before the mountains were settled in their place,

long before the hills I was born

when as yet he had made neither land nor lake

nor the first clod of earth.

When he set the heavens in their place I was there,

when he girdled the ocean with the horizon,

when he fixed the canopy of clouds overhead

and set the springs of ocean firm in their place,

when he prescribed its limits for the sea

and knit together earth’s foundations.

Then I was at his side each day,

his darling and delight,

playing in his presence continually,

playing on the earth, when he had finished it,

while my delight was in mankind.3

Linked images such as these of Athena and the Biblical wisdom figure demonstrate how the same archetypal reality springs up in different cultures and reveals its essential similarity, since it corresponds to a basic inner experience of mankind.

Psychologically, the Athena woman is a familiar figure, one who puts primary emphasis on spirit and intelligence, who is a companion and advisor to men, often without erotic involvement. In her past history one generally finds a positive relation to the father and a questionable relation with the mother—in other words, she is the creature of one parent. She is apt to be a woman who is particularly skilled at building bridges for the man between his mind and his feeling. She meets him more than halfway, and hence she is especially valuable as an intellectual and spiritual companion. Taken as an inner principle, an aspect of a man’s psyche, she is a most significant figure. Jung identifies the feminine figure of wisdom, Sophia, as the highest manifestation of the anima, the inner spiritual guide, even more developed than the purely spiritual image of the heavenly Mary. It is an image of woman that can relate a man to his depths in a profound and comprehensive way.

As a final observation, it may be noted that Greek philosophers were lovers of Sophia, as the word “philosophy” indicates, and Athena was closely connected with her. Hence, it is quite appropriate that Western philosophy should have had its birth in Athena’s city.