WHAT DOES the hero figure mean psychologically? The hero can be thought of as a dynamism toward a certain kind of psychological achievement or service, more concretely as a personification of the urge to individuation. The hero is linked both to the Self and to the ego but is neither one of them. The heroic urge, the urge to individuation, is an expression of the Self, the greater personality, but the conscious ego must relate to this urge and act on it in order to make it a reality. We could say, then, that the hero is more than the ego and less than the Self. It is important that the ego should not identify itself with the hero figure, although there is a widespread tendency in youth to do just that and to overestimate the ego’s power.

In considering this interpretation of the hero figure, it will be helpful to recall Jung’s definition of the term individuation. He says this:

In general, it is the process by which individual beings are formed and differentiated; in particular, it is the development of the psychological individual as a being distinct from the general, collective psychology. Individuation, therefore, is a process of differentiation, having for its goal the development of the individual personality.1

In another place he defines the individual as

. . . characterized by a peculiar, and in some respects unique psychology. The peculiar character of the individual psyche appears less in its elements than in its complex formations. The psychological individual . . . has an a priori unconscious existence, but exists consciously only in so far as a consciousness of his peculiar nature is present, i.e., so far as there exists a conscious distinction from other individuals.2

By this definition individuation and the growth of consciousness are really the same thing. Individuals are the only carriers of consciousness, which means that there is no such thing as “collective consciousness,” since, to the extent that a given psychic content is collective, it is not related to and carried by the individual, and hence is not really conscious. The myths about the hero figure depict a striving toward the realization of individual uniqueness, that is, toward becoming a carrier of more and more consciousness.

It is only proper to start with Heracles (more familiarly the Roman Hercules) since he is the hero of heroes in Western culture, his name almost synonymous with the hero function. Heracles and his twin, Iphicles, were the sons of the mortal woman Alcmene. Iphicles was fathered by Alcmene’s husband, Amphitryon, and Heracles was fathered by Zeus, who came to Alcmene in Amphitryon’s form. It is as though we have the image of ego represented by Iphicles, and the heroic function represented by Heracles, the difference between them becoming immediately apparent. Shortly after Heracles’ birth, Hera sent two poisonous serpents to the cradle of the twins. Iphicles shrieked in terror, but Heracles grabbed the two serpents by the neck and strangled them, depicting the difference in reactivity between the human ego and the heroic principle.

Heracles’ name means glory either by, through, or of Hera. Throughout his life Heracles was plagued by Hera—she was his enemy—yet his name indicates that his glory is somehow related to his connection with her, and in fact something about the harassment itself served to promote his achievement. This is reminiscent of Job being plagued by Yahweh, and suggests a divided state within the divine realm: one aspect of the divine nourishes and supports and the other aspect challenges and goads. In Job’s case, at the same time that he was suffering the results of Yahweh’s wager with Satan, he retained his trust in the redeeming aspect of Yahweh.

The features of the birth of Heracles exemplify the birth of the hero in general. This was first elucidated by Otto Rank in his book The Myth of the Birth of the Hero, which points out a number of common characteristics that can be seen also in the lives of two other heroes, Moses and Jesus.3 First, the hero almost always has a double parentage. Heracles’ double fathers were Amphitryon and Zeus. Moses had his own parents but was adopted by the princess of the royal household and raised by royalty, while Jesus, in addition to Joseph and Mary, had a suprapersonal parent in the Holy Spirit. A second typical event of the hero’s story is that immediately after birth he is abandoned or else subject to severe attacks or threats. Heracles’ life was put in danger by the two serpents sent by Hera; Moses experienced abandonment; and Jesus was threatened by the Massacre of the Innocents. A third common theme is that shortly after his appearance the hero child demonstrates miraculous or almost invincible powers, Heracles’ strangling of the snakes providing an example. In Louis Ginsberg’s Legends of the Bible we find the story that at Moses’ birth a radiance emanated from him and that he walked and spoke on his first day.4 Similarly, Apocryphal stories tell us that on the holy family’s way to Egypt miracles took place—wheat fields sprang up in one day and heathen idols broke and tumbled with the passage of the infant Jesus.

These instances reflect a theme that comes up not infrequently in dreams at important periods of transition: the birth of the wonder child. In psychological terms, the double parentage motif tells us that the urge to individuation has a twofold source: personal factors and also transpersonal ones. It stems from the care and loving attention that actual persons such as the parents give the individual, but it derives as well from the archetypal roots of its own being, from divine knowledge.

The miraculous powers of the divine child symbolize the power of the urge toward individuation. The child has contact with a source of extraordinary potency. At the same time, the hero child is exposed to great threat, symbolized by the dangers it encounters. When the potentiality for individuation is first being born, everything is against it. It is perfectly understandable that this special urge to develop into a unique being, different from all others and from conventional standards, cannot expect to find outer support. Others may simply have no interest in the new being, or, more commonly, the environment and conventionalities of all kinds oppose it, perhaps quite subtly. It may be opposed by being regarded as worthless. That can be a killing danger, of course, because something that is newly born requires attention and nourishment and is extremely vulnerable to indifference.

Heracles had a tempestuous youth. He was subject to fits of anger and in one such fury, with his great strength, he killed Linus, the music instructor, and was banished to the country as a shepherd. This was only the first of several states of violent possession that had important consequences. The image expresses the fact that individuation energy is dangerous when the conscious ego is still weak and undisciplined. Jung told the story about himself that as a child he was subject to bouts of rage that frightened him. On one occasion, when he had been waylaid by a gang of local peasant boys, he became possessed by rage and seized one of the boys by the feet and used him as a club to beat off the others. He was amazed by the strength that welled up in him, realizing that in such a state he could have killed someone. This possession is quite analogous to Heracles’, and indicative of what can happen to someone with an exceptional energy potential.

The majority of us cannot call upon that excess of energy, so we are easily tamed by conventional means. But a few people of the Heraclean type, falling victim to their surplus of individuation energy, must undergo Heraclean tasks of differentiation and transformation of that energy. The most significant feature of the Heracles myth began in such a fit of rage, in a state of madness sent by Hera, when Heracles killed his wife and children. It is surprising, of course, that a hero myth of ancient times would include such human fallibility in the supreme hero, but it is authentic psychologically, because it is just such an event that can engender the most profound effort at transformation of the raw energy. In his state of remorse and despair Heracles consulted the Delphic oracle on how to redeem himself and be purified. Receiving no response, Heracles then tried to steal the tripod of the oracle in order to set up one of his own to get an answer. He actually wrestled with Apollo for the tripod, an act reminiscent of Jacob’s wrestling with the angel or Menelaus’ wrestling with Proteus in order to extract some message, some understanding. The point is that Heracles was so insistent on knowing what he must do to be redeemed that Zeus eventually intervened, and he was told by the oracle that he must turn himself over as a slave to Eurystheus, his cousin. In order to work out his criminal behavior he must perform twelve labors.

This leads us into the image of the servant hero, of which Heracles is probably the first and best example. We have later expressions of this—almost all heroes perform tasks—but the service, indeed the state of slavery, that is specified in the Heracles myth is unique. It anticipates a later version of the same theme in Isaiah, which describes the suffering servant of Yahweh, and there is also a connection with the Biblical statement that “he who is first among you, let him be servant of all.” Heracles is an original example of the psychological truth that the finest aspect of the psyche serves by its very nature; it gives, rather than receives.

Heracles is obliged to perform labors, to undertake a great work, in somewhat the same sense that the alchemist undertook his task of the transformation of matter. Heracles’ question to the oracle, of how one can be purified after a violent possession, can be answered psychologically as “become a slave to the work of individuation.” This great opus of individuation is described symbolically in the twelve labors of Heracles.

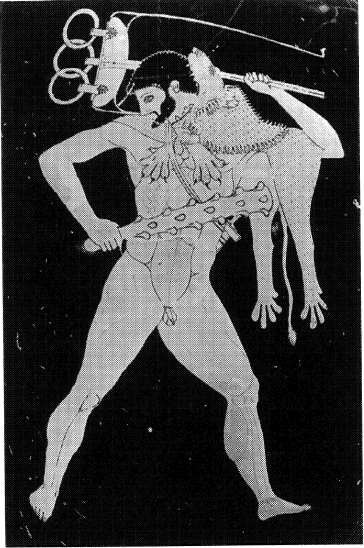

We can consider the labors to represent a series of encounters with the unconscious in its different aspects, and they are quite pertinent images to meditate on. The first task was to kill and flay the Nemean lion, which was ravaging the country. The lion is an image expressive of belligerent, masculine, instinctual energy. So Heracles’ initial task was to come to grips with the very energy that caused him to become a criminal in the first place. Not only did he have to kill the lion, he had to flay it, to skin it. But the hide of this beast was so tough it was impervious to all blades; nothing would cut it. Heracles managed to kill the lion by strangling it and then flayed it with its own claws. This is an early reference to a theme repeated in alchemy advising that a substance be dissolved in its own water, or calcined in its own fire. Such a prescription is nonsensical by all ordinary criteria, but psychologically we know that it refers to the fact that a complex, the psychic content that one has to deal with, contains its own potentiality for transformation if one can locate and relate to it; only by using its own energies can the work be done, since the ego does not have the necessary power. So it was with the Nemean lion—it could be flayed only by its own claws. Heracles clothed himself with the skin and wore it ever afterward, with the jaws of the lion sticking up over his head; it became a kind of cloak of invulnerability similar to a dream image in which one is wearing a fur coat; the lion’s skin is Heracles’ fur coat. He has mastered or come to terms with a certain primordial instinctual energy, and now it no longer threatens to overwhelm him. Now it protects him and belongs to him. We could say that this formerly wild aggressive energy is now in the service of the ego.

FIG. 16. Heracles, wearing the skin of the Nemean lion, steals the Delphic tripod. (Detail of an Attic amphora, c. 480 BC. Martin von Wagner Museum, University of Würzburg. Photo: K. Oehrlein.)

This passage from Nietzsche’s essay “Homer’s Contest” illustrates what the lion might have symbolized and what Heracles’ task would have signified for the Greeks:

[The Greeks have a trait of cruelty that really must strike fear into our hearts.] When the victor in a fight among the cities executes the entire male citizenry in accordance with the laws of war, and sells all the women and children into slavery, we see in the sanction of such a law that the Greeks considered it an earnest necessity to let their hatred flow forth fully; in such moments crowded and swollen feeling relieved itself: the tiger [read lion] leaped out, voluptuous cruelty in his terrible eyes. Why must the Greek sculptor give forth again and again to war and combat in innumerable repetitions: distended human bodies, their sinews tense with hatred or with the arrogance of triumph; writhing bodies, wounded; dying bodies, expiring? Why did the whole Greek world exult over the combat scenes of The Iliad?5

This cruelty is the Nemean lion that Heracles has to conquer; this is what the lion referred to for the ancient Greeks, and although we no longer have a Nemean lion today, we are not so remote from what it stands for.

After this first and all the subsequent labors, Eurystheus, the man who gave Heracles his orders, was terrified by the sight of the hero returning in triumph after overcoming these great monsters. Heracles had taken into himself the power of the creature he had overcome, and Eurystheus could not face him directly. He would only meet Heracles protected by a great urn, a scene represented on a good many Greek vases: Eurystheus peeking out of a huge urn as Heracles returns with one of his trophies. Eurystheus’ fear corresponds to that of the ego, which stands in awe of the heroic energy, and is well advised to be afraid of it; if it is not, it may identify with it.

Heracles’ second labor was to overcome the hydra of Lerna, a monster with poisonous breath that would generate two heads any time one was cut off. This is an apt image of a certain aspect of the unconscious that cannot be dealt with by ordinary means. One sees it represented in dreams in which the dreamer, encountering some small creature, perhaps an insect or reptile, tries furiously to stamp it to death, only to watch it grow bigger. The hydra has something of that same nature: one head is cut off and two emerge. Some new method had to be devised to deal with the hydra, so Heracles persuaded his nephew Iolaus to assist him, and as soon as one head was cut off, Iolaus immediately cauterized it, which prevented it from regrowing. This seems to refer to the application of affect: not only is there a discriminating operation, signified by the clean cut of the blade, but there is also an application of affective intensity—fire—that produces the cauterizing effect.

The problem of the hydra is probably related to repression, since another of its attributes was that one of its heads was immortal; even when it was cut off it remained invulnerable and it had to be buried under a big rock, a repressive operation. We can say that Heracles dealt with the hydra of Lerna by repressive measures, a stratagem that led in the long run to his undoing. After he had disposed of the hydra, he took its poison and used it thereafter to tip his arrows. As we shall see, the poison of the hydra finally destroyed Heracles himself.

The third labor required capturing the Ceryneian hind, a female deer sacred to Artemis, which nevertheless had brazen hooves and golden horns. The image of this deer suggests that a masculine value (the golden horns) was being carried by a feminine principle. The Artemis principle had to be encountered, then tamed and brought back as a part of masculine consciousness.

As his fourth labor Heracles had to capture the Erymanthian boar, the creature that killed Adonis and also Attis, the son and lover of the Great Mother Cybele. The boar can be thought of as the crude phallic power of the Great Mother that is still under control of the matriarchal psyche. To overcome the Erymanthian boar would involve the hero’s coming into contact with a certain aspect of primordial feminine power and mastering it.

Cleaning the Augean stables came next on Heracles’ agenda and was accomplished by diverting a river through them. They had accumulated vast quantities of manure, an image that has parallels in dreams of overflowing toilets with feces spilling out, and of long-neglected outhouses. Those are modern, individual versions of the Augean stables, indicating long neglect of the instinctive processes, and requiring Heraclean effort in attending to them and giving them their due.

The sixth task was to dispose of the Stymphalian birds, huge creatures with brazen beaks and feathers and poisonous excrement who lived in a swamp that was neither land nor water. They were scattered by the use of noisemakers like rattles and we can think of them as evil spirits, negative autonomous complexes that were exorcised by raising a counterspirit against them. The image of the Stymphalian birds and the way Heracles dealt with them might come to mind when one encounters people who, unable to stand normal silence, chatter perpetually. Perhaps they are compelled to make noise in order to frighten their Stymphalian birds away.

The hero’s seventh labor, the capture of the Cretan bull that was ravaging the island, involves symbolism taken up again in the myth of Theseus. The bull, along with the lion, represents an aspect of masculine, instinctual energy and is one of the manifestations of Zeus, who carried away Europa as a bull. It has a lengthy symbolism. The basic image of Mithraism was the sacrifice of the bull, and the bullfight ritual that still exists in Spanish cultures belongs to this same symbolism. In dreams the bull generally expresses the dangerous chthonic aspect of masculine power, the quality that Heracles is obliged to encounter and deal with. An example of this was a patient’s dream following a psychotic episode: the dream consisted of the simple statement, “The bull is loose.”

The next episode concerns the man-eating mares of Diomedes, who would feed his guests to them. The imagery here refers to coming to grips with the devouring aspects of the unconscious, which is not always hospitable.

The ninth labor is a little different. The hero was required to fetch the golden girdle of Ares worn by Hippolyte, the queen of the Amazons, a race of warlike females. The word amazon means “without breasts,” and the story relates that these women would amputate the right breast in order to be better archers. At the same time, to be born male in the world of the Amazons was a disaster, because a male child’s leg was broken at birth to ensure that it would grow up crippled. Here we have a picture of the matriarchal psyche, and to take the girdle of Ares from the queen of the Amazons meant redeeming the masculine principle, which was under subjection to the matriarchal aspect of the psyche.

The account of the tenth labor, the return of the cattle of the giant Geryon, who was located somewhere at the limits of the known world, takes us on a long, meandering journey in which Heracles travels all the way out beyond the Rock of Gibraltar and back, his main activity consisting of civilizing whatever he comes to. He tames wild beasts, founds cities, and colonizes various places he passes through—this is a portrait of Heracles as a culture hero civilizing the barbarians, foreshadowing what the Greeks in fact would eventually carry out in the Mediterranean basin.

As his penultimate task Heracles was to fetch the golden apples in the garden of the Hesperides, which were protected by a dragon that lay coiled around the tree—a setting, of course, reminiscent of the Garden of Eden. Heracles had to call upon the Titan Atlas to locate the garden and agreed to hold up the world while Atlas plucked the golden apples for him. Atlas saw a chance to get rid of his heavy burden, and would have left Heracles holding the world, but Heracles tricked him into reassuming the burden by asking him to take it back for just a minute while he placed a pad on his shoulder.

There is something analogous here to the story of Saint Christopher, the giant ferryman who carried across a stream an infant who got heavier and heavier until finally he was struggling under the weight of the whole world, after which he learned he had been bearing the infant Jesus. Here we have a similar idea. It tells us that the apples of the Hesperides and the whole image of paradise are expressions of wholeness, which cannot be reached unless one can carry the weight of wholeness, the weight of the world, on one’s shoulders. This is not a permanent task—it should not be that—but it has to be taken on for a moment. Then there is the problem of getting it off again.

On Heracles’ return with the golden apples, he met the giant Alcyoneus, who forced him into a wrestling match. The giant was constantly rejuvenated by contact with the earth, so that every time in the wrestling match that he suffered a fall, he was reinvigorated. Things went badly for Heracles until he realized what to do; he killed the giant while holding him aloft and not allowing him to touch the earth. Here again is the image of bearing a weight rather than letting it fall, which corresponds psychologically to what is required at a certain point in coming to terms with an unconscious complex. Such a pocket of energy and affect from the unconscious, which tends to take the ego by surprise and trigger an emotional outburst, must be held in awareness until it has exhausted its quantity of unconscious energy, until it has “cooled off.” If it is let go too soon, it is reinforced by its contact with the depths.

At last Heracles ended his servitude with the capture of Cerberus, the dog of hell. This seems to be the negative version of a previous task. The paradisal garden of the Hesperides represents the positive aspect of contact with the center, the Self, but here we have a descent into hell instead of an ascent into paradise. Heracles brought Cerberus up to earth, exposing him to consciousness, so that the horror of the dark side of the Self was seen and could no longer be doubted. By contrast, the apples of the Hesperides were a powerful token of the beatific aspect of the Self.

There is another episode in which Heracles, thinking he had been accused of stealing cattle by an old man named Iphitus, murdered him in a fit of rage. To redeem himself for that crime he became a slave of Omphale, an Anatolian queen, who dressed him in skirts and made him weave and amuse her. He succumbed totally to feminine domination. Once again we come upon a theme that is almost unheard of in a hero myth, but its true-to-life quality is striking. It implies that after living out of and serving the masculine principle so extremely, the hero must submit himself to the service of the feminine, a notion that we see again in medieval chivalry, where the knight would commit himself to the service of his mistress. It indicates the extent to which the male ego is obliged to strip itself of its masculine identity in the course of the individuation process.

Heracles is associated with various other feats, and one other important episode brings the hydra back into the picture. The story has it that Heracles wanted to marry Deianeira, but in order to do so he had to wrestle with Achelous, the river god, who also sought her hand. Achelous was a strange creature who could take three different forms: that of a bull, a speckled serpent, and a bull-headed man—not unlike Proteus, who was able to transform himself almost indefinitely. This is the theme of the monster that must be overcome in order to rescue the anima, and it tells us that the relationship function in a man has to be won; it is not given automatically but has to be carved out of the whole area of unregenerate concupiscence that he starts out with. This primitive desirousness is symbolized by Achelous, the river god.

Heracles overcame Achelous and won Deianeira as his wife. But at a river crossing, the centaur Nessus, who had offered to take Deianeira across the stream, attempted to rape her in the middle of the crossing. Heracles immediately responded by killing him with one of his arrows tipped in the poisonous gall of the hydra. As Nessus was dying, he said to Deianeira, “Take some of my blood. It is a love charm and if ever you’re in danger of losing the love of Heracles to another, you can apply this charm and it will regain his love for you.” What he gave her was his blood containing the hydra poison. Later, when Heracles became enamored of another, Iole, Deianeira made use of what Nessus had given her. She dipped a shirt in the poisoned blood and sent it to Heracles, thinking she would thereby win him back. But as Heracles put on the shirt it burst into flame and he could not tear it off. His only release was to lie down and be consumed by the flames of his own funeral pyre, at which point he ascended to heaven and joined the gods as a divinity.

There are some weighty implications in this symbolism. Many analogies to the crucifixion and ascension of Christ are present, and the story is worked out by means of naive images that tell us much about the primitive psyche and the nature of desirousness. The poison of the hydra, which had for so long made Heracles invincible, finally destroyed him. As we noticed previously, his victory over the hydra had been only partial; it seemed to smack of repression rather than of any decisive transformation. The Nessus episode suggests that the poison that cannot be permanently destroyed and finally turns against the hero can be thought of as primitive desirousness. This is what used to be called concupiscence, which seems to be at the very root of all organic life; it does not differ from original sin. The effect of the hydra poison takes place in the context of desirousness, of lust—the attempted rape by Nessus, the later desire of Heracles for a new mistress, and then the possessive desire of Deianeira. The myth is a dramatization of how this concupiscence, this primordial desirousness, finally burns everything that pertains to it, and the culmination only occurs when another fire, the funeral pyre, overwhelms the flames of desire. It represents a kind of ultimate purification in which a fiery purging of everything that is mortal in Heracles takes place—a final sublimation that transforms him to the eternal state. Although many of Heracles’ labors actually symbolize overcoming primitive desirousness, in the end he succumbed to all that he had been struggling against. Yet at the same time his failure was his final victory.

The story of Jason and the quest of the golden fleece is a second widely familiar individuation myth of the ancient Greek canon. It was a favorite of the alchemists for whom the golden fleece seemed identical with their own objective of making the incorruptible substance symbolized by gold. They considered Jason an early alchemist.

The tale begins long before Jason’s birth. There had been a crime that was to have led to the sacrifice of two children, Helle and Phrixus, but they were able to escape owing to the miraculous appearance of a ram with golden fleece (this calls to mind Isaac’s deliverance from Abraham’s effort to sacrifice him by the appearance of a ram in a thicket). The ram with the golden fleece carried the children from Greece to Colchis, on the far side of the Black Sea. Helle was lost when she fell into the Hellespont, which took her name, but Phrixus survived and became an exile in Colchis, where the ram was sacrificed and the golden fleece was hung up as a shrine.

The ram with the golden fleece signifies a masculine aspect of the Self. Its golden fleece suggests its supreme value, but its masculine character indicates that it is only a partial expression of the Self, and that limitation runs through the entire myth: much is accomplished, but incompletely. We recognize this theme from the very beginning in the one-sided nature of the symbol and in the early loss of the girl child Helle. The feminine element is lost repeatedly and then at the end, in retaliation, destroys the whole enterprise.

The situation that led up to the expedition is equally instructive psychologically. The initial crime committed in the past, the effects of which had impoverished the country, had to be expiated. This is a version of the theme of original sin that appears in both the Greek and Hebrew traditions: in some early psychological period a sin was committed that now needs restitution. In psychological terms, this refers to some crime against the natural state of things that is necessary for the ego to initiate its own development. An act of violence against the original state is the basis on which the ego evolves and takes for itself energies belonging to nature, but that also has the effect of alienating the ego from the natural condition. In the Jason myth, a kind of sickness lies upon the land because of a missing vital value; the land has been separated from its central meaning, and sooner or later the fruits of that crime come to the fore and must be dealt with. This was Jason’s task.

The account of the Argonauts opens at the time when the land was in distress and Jason was a young man, just starting out in life. When Jason was a child, his life had been in danger and he had been smuggled out of the royal palace to be raised by Cheiron, the centaur. When he was fully grown, he returned home to confront his uncle Pelias, who had usurped the kingdom. An oracle had warned Pelias to beware a man with one sandal, and the story relates that as Jason was heading for the city, intending to demand the throne as his rightful inheritance, he offered an old crone assistance in crossing a river. (Crucial events, often mishaps, tend to happen at rivers, as Jung has noted; it is the theme of the dangerous transition.) As he carried her across the river, the woman grew ever heavier and it turned out that she was Hera herself. Barely making it across, Jason lost one of his sandals, and here again is the Saint Christopher reference: it is as if the hero, as he proceeds to meet his destiny, encounters a certain aspect of the unconscious that leaves its mark on him. A variation on the theme of laming, Jason’s lost sandal corresponds, for example, to Captain Ahab’s wooden leg in Moby-Dick and to Oedipus’ damaged foot.

When Jason arrived in the city and demanded the return of his throne, Pelias agreed to do so if Jason would bring back the golden fleece and with it the spirit of Phrixus. The oracle had pronounced that the land would not prosper until this was done. Jason thereupon set forth on the voyage of the Argonauts, the most remarkable assemblage of heroes ever brought together for such an adventure.

The first stop of the voyage was the island of Lemnos, where the Argonauts found that the Lemnian women had been insulted by their husbands and in revenge had slaughtered them all. Jason and his group were accordingly welcomed to the beds of the Lemnian women for the sake of the children they could father, and the problem was to get the men back on the ships and on their way again. It is as if, on such a trip to the unconscious, when there is a first reconciliation of opposing factors, a strong temptation arises to succumb to the pleasure urge, to settle for that, and to forget about the goal that is still far distant.

Back on the ships, the crew then suffered the loss of Jason’s armor-bearer, Hylas. A beautiful young man, he was drawing water from a spring on another isle when a nymph of the spring fell in love with him and drew him into the water, where he drowned. This suggests a Narcissus-like form of immature romanticism that falls into the unconscious; the implication is that certain qualities cannot survive the journey into the unconscious, but sink into it and perish.

The Argonauts then met an arrogant brute named Amycus, who required that everyone who passed by fight him or be thrown into the sea. Polydeuces accepted his challenge and vanquished him, which we can see as an encounter with arrogant attitudes that must be overcome if the journey into the unconscious is to proceed further.

Next, the crew came upon Phineus and the Harpies. Phineus had a gift for prophecy, but he told too much about the future and Zeus punished him by sending the Harpies, nasty birds who would snatch his food whenever it was laid out and leave a repulsive stench. The Argonauts, however, needed to get directions from Phineus to continue their voyage, and Phineus insisted on being freed from his plague of Harpies before he would give them. This seems to be a picture of contaminated intuition. Intuitive knowledge is necessary if the Argonauts are to proceed, yet it must be purified before it becomes serviceable. One does encounter occasions of misused intuition, which is really not available for conscious purposes but is something the individual falls victim to; it is more a plague than a benefit. Those with a certain kind of extraverted intuition, for instance, can sense what is expected of them by others and then are obliged to serve that expectation, not as a matter of choice but as a compulsion. After Phineus was relieved of the Harpies, he told them the course to follow and how to get through the Symplegades. These were two rocks that crashed together repeatedly; the boat had to slip between them. It is an image of the opposites: one must move between the opposites to go on, but with the risk of getting caught in their clashing.

Eventually, the Argonauts arrived at Colchis where King Aeëtes proved willing to turn over the fleece, providing certain seemingly impossible tasks were performed: two fire-eating brazen bulls must be yoked, a field must be plowed with them, then sown with dragons’ teeth, and the armed men that sprang from that sowing must be killed. What seems to be indicated by all of this is that the ego must expose itself to the primordial powers of the masculine archetype represented by the fire-breathing bulls, and the opposites that arise in the form of armed men must also be dealt with. In the event, when the soldiers sprang up, a stone was thrown in their midst and they turned against and annihilated each other. The psychological implication of that image is that one must not identify with one of a pair of warring opposites. If, in one’s own psychic conflicts, one can refrain from such an identification, the opposites wear themselves out, leading to a transformation.

None of the tasks could have been carried out, however, without the help of Medea, the king’s daughter, who fell in love with Jason at her first sight of the hero. Medea was a sorceress and when Jason promised to take her home in the ship as his wife, she gave him a magic ointment that made him invulnerable for a day and thus enabled him to perform the necessary feats. This help from the anima, who had contact with arcane powers—we could say, with deep layers of the unconscious—was indispensable to his success. She continued to help him when later, King Aeëtes went back on his word to give up the fleece and Jason had to steal it and flee Colchis, followed by the king’s ships. From on board the Argo, Medea delayed the pursuing forces by killing her brother Apsyrtus and cutting up his body, throwing one piece after another from the ship. As the father paused to pick up each one, the Argonauts were able to escape.

We are dealing with a version of the widespread theme of dismemberment; here, it is carried out in the service of the hero’s task—to get away, get back to consciousness. There are different ways of interpreting this theme, but essentially in this myth Medea’s relationship to her brother was sacrificed in the interests of her relationship to Jason. Although the image is repulsive, it represents the dissolving of a certain concretization of libido so that it may become available for a new kind of relationship.

Once the pair returned to Greece, Medea performed yet another service for Jason. Pelias, the usurper, had killed Jason’s parents and vengeance was due. Medea tricked Pelias’ daughters into killing their aging father by cutting him up, on the assurance that he would be put into a pot and Medea, the sorceress, would magically rejuvenate him. Thus Pelias was dismembered just as Medea’s brother had been, and both times the responsibility for these actions was left in the hands of Medea, as Jason’s anima. Jason, the masculine ego, avoided responsibility, a fatal mistake on the path to individuation, and a suggestion that there was trouble ahead.

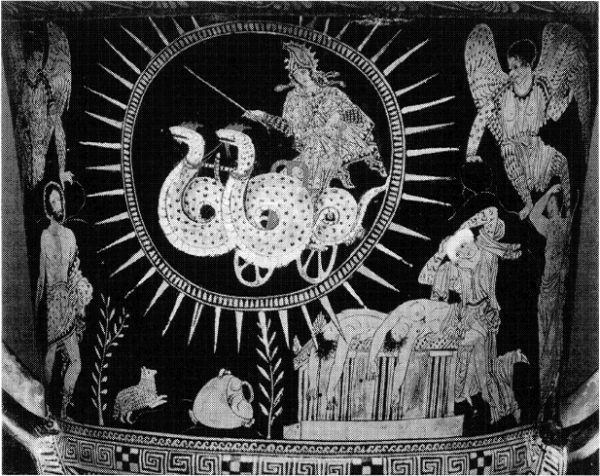

Finally, for reasons of expediency, Jason decided to leave Medea and marry the princess of Thebes (a return of the Deianeira-Heracles theme). Medea sent a magic robe to the princess, which burst into flames and destroyed her when she put it on. Medea then killed her own children in revenge against Jason and finally disappeared in a dragon chariot into the sky. This was the end of Medea, as far as Jason was concerned. The whole process, the whole Argonaut journey, had failed, essentially because of the disregard of the feminine element. That was presaged at the beginning, when the child, Helle, drowned, and it continued in Jason’s use of Medea’s powers without honoring his promises to her. Psychologically speakings, a central feature of this myth is the consequence of misusing the anima, the man’s feminine side and soul. As with Medea, the anima used to advance the aims of the masculine ego and not granted respect for her own reality, turns bitter and is lost to the man. Ultimately, Jason is said to have lost the favor of the gods and to have become a homeless wanderer.

FIG. 17. Medea escapes in a dragon-drawn chariot, while her dead children lie on an altar and Jason looks up after his departing wife. (The Medea krater. Earthenware with slip decoration and added red, white, and yellow, h. 50.3 cm. Attributed to the Policoro Painter, South Italy, late 5th–early 4th century BC. Copyright Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Fund, 91.1.)

The story of Jason and Medea seems to live itself out continuously. A man will meet a woman who captures his anima projection and through that projection he will temporarily get a sense of worth and competence and masculine power that carries him on in the life process. But then, since the energy came out of the projection and was not really his own achievement, the time of reckoning will come when the projection fails and he will be left as Jason was with regard to Medea. The job of psychic integration is still to be done. We see this phenomenon again in the Theseus myth in which he makes a relationship to Ariadne and uses her help, but then abandons her before he gets home. Although we have plenty of examples of how this breakdown can apply to the psychology of modern men, it also indicates the stage of development of the early Greek psyche. It is as though the feminine principle could not be assimilated in any complete way at that time because the society was still too close to the matriarchal phase and the masculine principle was not securely established. The masculine could not achieve a balance with the feminine, hence the most that could be done was to exploit the feminine principle and then drop it again. The result was that the anima turned into bitterness.

We may find in this an underlying explanation for the eventual fall of the ancient world: it could not assimilate the anima and the feminine principle. Certainly in Hellenistic times we note the development of a pervasive bitterness; a kind of rending sadness seems to run through most of Greek wisdom. Stoicism had an undercurrent of despair, and we see its ultimate expression in Sophocles, who gave vent to this prevalent feeling in these lines from Oedipus at Colonus: “Not to be born is, past all prizing, best; but when a man hath seen the light, this is next by far, that with all speed he should go thither, whence he hath come.”6 If that is the ultimate wisdom of life, it is a counsel of despair and reason enough for the decline of ancient civilization.

The myths of Theseus and Perseus follow each other because the former concerns the encounter with the father monster and problems of the father complex, while the latter deals with the mother monster, the mother complex. It is helpful to compare the two myths.

Like other heroes, Theseus had a double parentage. He was fathered by King Aegeus, who was on a visit in Troezen, but according to some stories, his mother, Aethra, was visited by the god Poseidon. So his father on one hand was a god and on the other, a mortal. In either case, when Aegeus left for Athens he told Aethra he had deposited his sword and sandals under a great rock and that when his son was sixteen years old she was to take him to the rock. If he was able to lift it and retrieve the sword and sandals, he would prove that his parent was Aegeus, and he should then come and visit his father.

This echoes a characteristic theme in which the son, when he comes of age, is required to undergo some ordeal in order to receive his heritage from his father. Such a rite is involved in all of the basic choices of a young man, outstandingly in the determination of his vocation, the most crucial step he must take. He will be handicapped in deciding it unless he is in relation to his own inner masculine heritage. Does this mythological image apply to women and their choice of vocation? It is Erich Neumann’s viewpoint,7 as it is mine, that the hero myth also pertains to women, that these myths deal with the process of developing consciousness as such, and that process is symbolically masculine whether one is male or female.

After lifting the rock with ease, and recovering the sword and the sandals, Theseus set out on his journey to Athens to meet his father. Rather than taking the safe route directly by water, Theseus chose to go along the semicircular coast, which was known to be populated by criminals. He dreamed of performing heroic feats by engaging these public enemies.

On his way, Theseus had a series of ordeals in which he encountered various aspects of negative, unconscious masculinity. The first was a desperado named Periphetes, who waylaid travelers and clubbed them to death. Theseus grabbed his club and beat Periphetes to death. A feature of all his encounters was that the ruffians had done to them what they did to others, illustrating a basic psychological law: the way one behaves, so one is treated. That is true on the unconscious as well as on the conscious level. Periphetes was clubbed himself, and then Theseus made the club his own, so a bit of masculine power was won and was made available to the ego.

The next thug he met was a man named Sinis, the “pine bender.” He would bend a pine tree to the ground, and then ask a passing traveler to hold it with him. As soon as the traveler would seize the tree, Sinis would release his grip and the traveler would be flung to his death. Theseus disposed of Sinis by that same method: he arranged it so that Sinis was thrown by his own tree. This is a strange image. Psychologically, it has something to do with distorting a natural growth tendency and then making use of the backlash of it. The bending of the natural tendency can only be held a short time and then it springs back to its original position. We might think of this as an image of excessive self-discipline that cannot last forever because it requires too much energy; sooner or later the natural forces exert their backlash and throw the ego off again. These images are the product of centuries of folk polishing, so to speak, and they have a lot to say about the human psyche.

Theseus then had to face Sciron, who was seated on a high rock where he forced passersby to wash his feet. While they complied he kicked them off the cliff into the sea where a great turtle devoured them. That would refer to the danger of succumbing to false humility, to a servile attitude, as the washing of the feet suggests. In other words, this chap took advantage of the individual’s tendency to be obeisant or subservient, and then destroyed him for it. Theseus repaid him in kind.a

Sciron was followed by Cercyon, a vicious fighter who would challenge each traveler and then crush him to death in his embrace. Theseus got the better of him by making use of the strategic principles of wrestling, which he invented. He overcame Cercyon not by brute force but by the application of conscious skill and inventiveness, suggesting that consciousness must use its own principles in dealing with the unconscious forces and not try to meet the unconscious on its own ground.

The final criminal the hero ran into is the best known: Procrustes. This man captured travelers and laid them out on his bed. Those who were too long for his bed he chopped off so they would fit, and those who were too short he stretched out. This is such a striking image to describe a well-known human tendency that it has become popular in general usage. A procrustean bed is a rigid, preconceived attitude that pays no attention to the living reality one is confronting, but brutally forces it to conform to one’s preconception. It describes the danger of the ego’s tendency to judge itself by alien standards, thus suffering an amputation or distortion of its own natural reality, the brutal effects of living by an unconscious “ought.” Procrustes’ bed is an ought.

Finally arriving in Athens, Theseus was almost poisoned by Medea, who was Aegeus’ wife at that time. She told Aegeus that the young man was a spy and Aegeus was about to become an accomplice to his murder when at the critical moment he caught sight of the sword he had left for his son years before, and dashed the poison cup from Theseus’ hands. What does that mean? One interpretation would be that just as the ego is completing one stage of relation to the father principle, it almost succumbs to a poisonous regressive maternal yearning within itself. In addition, we can say that there is a reluctance on the part of the powers that be to let the new power come into its own. The status quo wants to continue, and any newly emerging force has to fight it out if it is not to be overcome.

Theseus, however, was recognized in time by his father and was welcomed with open arms. So he reestablished his relation to the father, the inner masculine principle to which he owed his being. But no sooner had that happened than another trial presented itself to him. In Crete, King Minos had once prayed for a demonstration of his special relation to the god Poseidon and he was given that recognition by the emergence of a beautiful white bull from the sea, with the understanding that the bull would immediately be sacrificed to Poseidon. But Minos thought the bull too beautiful to give back, so he sacrificed an inferior one. Poseidon, in retaliation, arranged that Minos’ wife Pasiphaë should develop a passion for the white bull, and indeed she coupled with it and gave birth to the monster called the Minotaur, which had a bull’s head and a human body, such a dreadful creature that it had to be hidden away in a labyrinth. The story tells us that when one takes for oneself what belongs to the divine powers, one breeds monsters. It does not go unnoticed when the ego, as Minos did, uses the transpersonal or instinctive energies for itself alone.

Then, because of offenses to the Cretan king (at this time, Athens was subject to Crete), it was decreed that every nine years Athens must supply seven youths and seven maidens to be fed to the Minotaur. Theseus arrived on the scene just when a new batch of youths and maidens was prepared to set sail to meet the monster, and he quickly offered himself as one of the tribute youths, with the intention of destroying the Minotaur.

Here is a picture of human contents being turned over to monster purposes, a state of affairs that had come about because the original bull from the sea was not voluntarily sacrificed to the god. The primitive instinctual energies that are signified by the bull were not sacrificed to a higher purpose, and the price of that failure was that human qualities represented by the tribute youths then had to be sacrificed to the bull. In place of a progressive developmental movement that would amount to an enlargement of consciousness, the more conscious humans were sacrificed to the less conscious Minotaur: a regressive movement.

This again brings up the symbolism of the bull. We know from archeological work in Crete that a remarkable sport existed there, a kind of bull dance in which acrobats would grab the horns of a bull and somersault onto and off its back, a prototype, clearly, of what has lasted into our own day as the bullfight. A human being’s meeting and mastering the power of the bull seems to have a deep-seated psychological meaning. The bull stands for something that must be challenged and shown to be inferior to human power. Without this level of meaning, the elaborate rituals of confrontation with the bull cannot be understood psychologically.

Another important symbol system that made a great deal of the bull image was Mithraism, which became the major religion of the Roman legions in the first few centuries of this era, and according to some authorities, if Christianity had not supervened, would have become a worldwide religion. It had as its central image Mithras sacrificing the bull.

In psychological terms, the bull is the primordial unregenerate energy of the masculine archetype that is destructive to consciousness and to the ego when it identifies with it. Therefore, it must be sacrificed, and the sacrifice brings about a transformation, so that the energy symbolized by the bull serves another level of meaning. Seen this way it is not too much to say that the sacrifice or overcoming of the bull symbolizes the whole task of human civilization.

The Theseus myth is the story of encounters with both the good father and the father monster. Aegeus, the good father, helped his son to find him and then welcomed him. But when Theseus arrived in Crete he immediately encountered the negative father, King Minos. No sooner had the ship from Athens arrived than Minos espied one of the Greek maidens who appealed to him and was about to rape her on the spot. Theseus intervened, and in the altercation that followed Theseus proved his own relation to Poseidon by retrieving a ring that Minos threw into the sea. In this initial exhibition of his monstrous nature a certain correspondence between Minos and Minotaur is indicated and the very names suggest the similarity, making it clear that Theseus was confronting the masculine monster, the negative aspect of the father image, something that sons not uncommonly have to overcome in dealing with certain kinds of fathers.

It is interesting that although Aegeus was the good father, his consort, Medea, was destructive, a negative manifestation of the feminine associated with the positive father. In Crete there was just the opposite: Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, turned out to be helpful to Theseus—the bad father was accompanied by the good anima. This pattern has psychological implications. At a certain stage of development the positive relation that the son enjoys with the father hides a negative, dangerous aspect in the unconscious, signified by Medea. But as soon as it is realized that the relation to the father is not so purely positive as was thought, that actually the father can also be a negative and somewhat dubious figure, and as soon as that realization leads to appropriate behavior, then the positive anima (signified here by Ariadne) can emerge.

To meet the Minotaur, Theseus made his way into the labyrinth with the help of Ariadne, who was the Minotaur’s half sister. It is as if she knew about him because she shared some of his qualities, and this reflects the characteristic theme of the anima linked with the monster in some way. Usually, the anima is held in bondage by a feminine monster, as in the myth of Perseus, but here we see a masculine monster that was not holding Ariadne in bondage but was associated with her; she was able to leave only upon his death. The Minotaur was successfully mastered with the help of the feminine, Ariadne providing a ball of thread, which was the essential guidance. We can consider Ariadne’s thread as the thread of feeling; it is safe to confront one’s unregenerate wrath and lust and instinctuality providing one can hold onto the thread of feeling relatedness that gives orientation and prevents one from getting lost in the labyrinth of the unconscious. We all have a minotaur in the labyrinth of the soul and until it is faced decisively it demands repeated sacrifices of human meanings and values. Thus, the principle of Eros or relatedness enabled Theseus to meet the Minotaur, and there is a parallel to this image in the medieval idea of the unicorn, that wild, irascible, and completely unmanageable creature that is tame only when in the lap of a virgin.

It is an evocative image, the labyrinth with the Minotaur prowling it. The implication of this particular myth is that at the stage in which Theseus negotiates the labyrinth there is a destructive aspect to the unconscious that requires a continuous tribute of human sacrifice—an intolerable state of affairs that cannot stop until the monster is overcome by a conscious encounter. Another way of looking at the myth is to see the Minotaur as a kind of guardian of the center. Surely the labyrinth is a representation of the unconscious, since it is that place where there is danger of getting lost. One of the aspects of the labyrinth, according to mythology, is the presence at the center of something very precious. That precious thing is not specified in the Theseus story, but it is implied in the person of Ariadne. Ariadne was the fruit that Theseus plucked from his experience with the labyrinth.

Theseus found the Minotaur by throwing down Ariadne’s ball of thread, which rolled along unwinding itself, leading him to his destination—an image almost identical to one in an Irish fairy tale called “Conn-Eda,” in which the hero cast an iron ball in front of him and followed it as it rolled on its way, leading him to a city where his various adventures took place. These are images of following the round object, the symbol of wholeness. The sphere is a prefiguration of the goal, the goal of totality. The ideas of wholeness and center are related to each other; they are part of the same symbolic nexus, so one might say that the round ball will automatically roll to the center. The fact that the sphere has an autonomous power to roll to the center suggests that it is also the path to individuation rolled up into a ball.

FIG. 18. Theseus fights the Minotaur. (Detail of an Attic stamnos, c. 470 BC. Copyright British Museum, London.)

Theseus did as he was instructed by Ariadne and was able to overcome the Minotaur and find his way out of the labyrinth by means of the thread, the principle of relatedness. To understand what this motif could mean, one might imagine oneself in an agitated, enraged state, the Minotaur bellowing within. To confront one’s fury will be safer, given the thread—a sense of human rapport and relatedness—so that one will not get lost in the rage and fall into identification with it.

Theseus left Crete with Ariadne, but he broke his promise to marry her. On the way back to Athens they stopped at the island of Naxos, and there are different versions of what happened there (indicating multiple symbolic meanings). One version is that Theseus tired of Ariadne; after all, she wasn’t of any use to him anymore; he had achieved his purpose, and so he sailed off and left her. Another story is that the god Dionysus claimed her. The basic meaning, however, remains the same—the connection between the heroic aspect of the ego, Theseus, and the helpful anima could not be maintained. We witnessed a similar fate in the case of Jason and Medea, and we may assume that it signifies something of the same sort in the Greek psyche of that time: a stable, conscious assimilation of the anima could not be sustained. Although Ariadne was separated from the baleful shadow of her monstrous brother, she must remain related to the gods, so to speak—Dionysus, in her case—and was not yet ready for full participation in the human conscious realm. She had to remain largely an unconscious entity.

There is a further important episode of the story. When Theseus had departed from Athens, it was understood between him and his father that on his return, if he was successful, he would take down the black sails of his ship and hoist white ones. But he forgot about the agreement, and when his father spied the ship returning with its black sails, in his despair over what he took to be his son’s failure, he threw himself off the cliff into the sea (which then took his name: the Aegean). We know that forgetting is meaningful, and it is part of the central significance of the myth that the father, Aegeus, should die. Theseus had now become the father, so to speak, overcoming his dependent relation to the father figure and the need for the father to mediate the masculine principle. With the death of the father the individual becomes directly related to the masculine principle himself.

Theseus appears again in a different role in the myth of Hippolytus, already touched on in the discussion of Aphrodite. There, Theseus played the bullish father in his relations with his son Hippolytus. As we saw, the young man had incurred the wrath and vengeance of Aphrodite by his devotion to Artemis and his rejection of love. She contrived that his stepmother, Phaedra, should fall in love with him, and when he rejected her advances, Phaedra told Theseus that he had molested her. That is an ancient theme, which arises when a younger man is living in the household of an older man but remains subordinate too long. His subordinate status is challenged symbolically when the man’s wife takes him for a man, not a boy. The erotic complications initiate the necessary conflict between the younger and the older man.

Theseus was furious when he heard Phaedra’s story. He believed her lie and prayed to Poseidon for revenge on his son. Poseidon sent a monster (some versions say a bull) which came out of the sea and frightened Hippolytus’ horses when he was driving along the shore. He was tossed from his chariot and dragged to death. One way of seeing this is that Hippolytus had failed to meet the challenge of a new level of development, to realize himself as a mature erotic being. What he had consciously rejected came back in a negative form. Hippolytus’ problem can be seen as the need to accept a fuller masculinity. At the immature level, the woman belongs to the father and Phaedra was the father’s woman, hence Hippolytus dared not have a woman. The monster that came out of the sea and pursued Hippolytus can be seen as his own rejected masculine instincts that had not been faced, the very thing that Theseus faced in the Minotaur.

A patient once provided a vivid example of this theme. He had a bullish type of father who drove him to excel in various ways. This aggressiveness became interiorized and led to an inner pushing, a compulsive need to achieve, that went quite contrary to his own actual nature. His achievements were essentially hollow; he was living out the situation at the beginning of the Theseus story, submitting Athenian youths and maidens, internally, to the inner Minotaur. His real human meanings and human purposes were being fed to this brutal monster. On the night that he first decided to enter analysis he dreamed that he had to go through a maze, and at the end of the maze was the man who became his analyst. Exactly one year later to the day he had this dream:

I was in a prison maze. Suddenly I saw an opening, the way through. I dashed down the long hall. I expected gunfire but I caught them by surprise. I crossed over the boundary. I knew I was free and now others would be also. It was as if I had performed a yearly ritual and now others would be free. I turned around and came back. As I walked back different people came toward me, as if they were coming out of their graves. They were old and young, men and women. I stopped each one and gave a deep, guttural sound. I was passing my freedom on to them.

Here the imagery is lifted wholesale out of the Theseus-Minotaur story, demonstrating that it is still operative symbolism—we are not just dealing with ancient history.

According to one version of the Perseus myth, the father of Perseus’ mother, Danaë, had been told by an oracle that a grandson would depose him. For that reason he had his daughter locked up in a brass-walled dungeon to keep her apart from men. But Zeus came to her in the chamber as a shower of golden rain by which she conceived Perseus. Another version had it that Danaë was seduced by her uncle, the hostile brother of her father, and because of this illegitimate conception, she was confined to the dungeon.

This is the ambiguity that appears repeatedly in the myths; like the double parentage theme, it poses a question about the origins of the hero, in this instance: is this a divine conception or is it an illegitimate one? Symbolically, the two are equivalent, because if the conception does not occur under human auspices, if it is not legitimized by human mores, then it is beyond the pale and takes on transpersonal meaning and the quality of divinity. We are on familiar ground if we think of the legends surrounding the birth of Christ. The canonical sources speak of the birth as a conception through the Holy Spirit, something like the shower of rain that came to Danaë. However, some legends current at the time had it that Mary became illegitimately pregnant by a Roman centurion.

The phenomenology of this image is important in dreams. Very often, early dreams dealing with the emergence of the Self depict the birth of an illegitimate child, or perhaps the birth of the child unites the races—maybe the child is half black and half white. Just those things that are beyond the pale and have been considered unacceptable by conscious standards accompany this birth, because the Self, by its very nature, transcends the rules of the ego.

It is worth noting how the ancient writers used the image of Danaë. Sophocles compared her to Antigone, who had dared to defy the tyrant Creon’s decree that her dead brother, Creon’s rebellious enemy, be left unburied. Burial was profoundly important to the ancient Greek mind, and Antigone proceeded to bury her brother despite the prohibition. In punishment she was walled up in a cave to perish. Sophocles then says this about her:

Even thus endured Danaë in her beauty to change the light of day for brass-bound walls; and in that chamber, secret as the grave, she was held close prisoner; yet was she of a proud lineage, O my daughter, and charged with the keeping of the seed of Zeus that fell in the golden rain.8

Sophocles perceives that Antigone, in observing the divine law even when breaking man’s law, was of the same nature as Danaë, who kept the seed of Zeus to give birth to the hero Perseus. Psychologically, this image suggests that the birth of the individuation principle is a dubious, ambiguous happening that entails being shut off from the world at large. That was where Zeus encountered Danaë, shut up in her brass-walled prison.

The birth of Perseus was characteristically followed by the hero’s rejection and abandonment. Perseus and his mother were cast into the sea in a wooden chest, that is, were thrown into the unconscious, with the assumption that they would perish and never be heard from again. But in a miraculous way they landed on the island of King Polydectes and there Perseus was brought up.

At a time when wedding gifts were being presented to the king, the young Perseus, having nothing material to give, impetuously offered the most extravagant service conceivable, namely to bring the king the head of Medusa. The rashness and arrogance of the offer are built into the myth so that we have to take them as expressing some aspect of the individuation process: they apply to those stages where a careful and deliberate weighing of the odds would never allow one to get moving. If one had awareness in advance of what the prospects were, psychological development would not get very far; it probably would not get out of the womb. If Perseus was going to get somewhere, he had to make a daring leap. Then he was in for it; he had to go through with it.

This brings us to the image of the Gorgon Medusa and how we are to understand her. She is a common motif in Greek art. Greek pottery and some of the older Greek sculpture and architectural friezes show again and again the picture of the Gorgon, a ghastly woman with teeth and tongue protruding and hair made up of writhing snakes. The prominence of this image of horror in early Greece seems to portray what Nietzsche recognized so forcibly—the closeness of the Greek mind to the primordial depths out of which it had recently emerged. Thus the Greek sensibility encompassed a keen awareness of the horror of existence just below the surface, in a way that we pampered, civilized people are usually spared, and it was this that gave everything they did and everything they produced an intensity that has never been equalled.

Medusa is an expression of that dreadful level of existence that, if one looks at it very long, has petrifying effects, and we are told that her image was so fearsome that to gaze upon it was to be turned into stone. She can, of course, also be seen as the negative mother archetype in its most terrifying aspect, able to immobilize the ego so that all that is moving and flowing and changing and spontaneous is utterly halted. This is the very image that the young person must encounter and deal with if he is going to make his way into life. He has to confront the horror of existence itself if his life is to proceed and develop. That is what Perseus did.

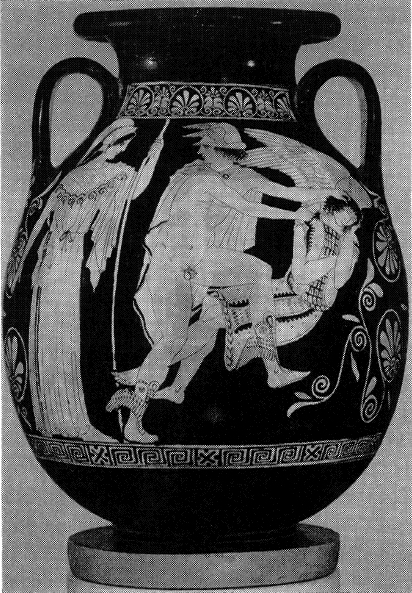

In this myth we find excellent examples of the helping deities of the Greek Pantheon. The two that came to Perseus’ assistance were the typical helpers: by Hermes he was furnished with what is usually called a sickle, a blade with which to cut off Medusa’s head, and from Athena he obtained a polished shield that was also a mirror, which enabled him to kill the Gorgon without having to look directly at her and become frozen in stone. There were some initial skirmishes with the female powers, since he had to seek out the Graiae in order to learn the way to Medusa. He stole the single eye and tooth they shared and so extracted from them directions to the three Gorgons. Finally, viewing Medusa by means of his mirror shield, he cut off her head. Instantly, out of the decapitated body sprang Chrysaor, a warrior who fathered future monsters, and more significantly, out of the severed head flew Pegasus, the winged horse. Here is a striking image of released libido. It is as if the decapitation of the Medusan horror had the effect of transforming the negative energy contained in her and releasing it into positive, creative power, signified by the horse, a symbol of physical energy that is at the same time winged. Pegasus later started the Peirene spring flowing, the spring of the Muses, with the powerful stamp of his moon-shaped hoof. So the arts derived from Pegasus’ libido but their ultimate source was Medusa, since Medusa was the mother of Pegasus.

On his way back from his encounter with Medusa, Perseus came upon Andromeda, who was chained to a rock as a sacrifice for the crimes of her mother and was being threatened by a sea monster. Perseus destroyed the monster and released Andromeda—a typical image of the captive anima who must be freed. It is another version of the freeing of Pegasus through the destruction of the Medusa monster, but on a more developed level, signifying the emergence of the feminine relatedness function out of its instinctive, monstrous origins, here represented by the sea monster.

FIG. 19. Perseus attacks sleeping Medusa, looking away from her to Athena to avoid being turned into stone. (Attic pelike, 5th century BC. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1945.)

The reflecting shield of Athena is of particular importance, because without that device Medusa could never have been faced and transformed. Given to the hero by the goddess, the embodiment of wisdom herself, Athena’s mirror shield is an image of the civilizing process, how it takes place, and how human consciousness is able to overcome the primordial horror represented by the Medusa. The myth tells us that it takes a mirror to overcome or deal with the elemental terror of what exists in the unconscious. The primary feature of the mirror is its ability to produce images; it shows us what we otherwise cannot see for ourselves because we are too close to it. Without a mirror, for instance, we would never even know what our face looks like; since we are inside looking out, there can be no self-knowledge, even the elementary self-knowledge of what we look like, unless there is some device that can turn the light back on us, unless there can be a reflexive movement. The whole process of consciousness, in both the individual and collective sense, is served by an instrument that produces reflections, images giving us an objective sense of what we are. Athena’s mirror, we should remember, is showing us an image of something we dare not look at directly; to grasp what we are dealing with, we need an image of it, we need to see it indirectly, which allows a more objective view. Surely it is not an accident that the term “reflection” refers to the specific capacity of human consciousness, the capacity to consider itself. That is the function of the mirror, and it is also the capacity of human consciousness to turn back on itself in self-critical, self-observing, self-scrutinizing reflection.

All art forms, literature, and drama are basically mirroring phenomena. Shakespeare tells us that in Hamlet’s remark about the nature of the drama: “The purpose of playing . . . is to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”9 When we attend the theater we are, in effect, being mirrored. Jung called the theater the place where people work out their private complexes in public. We discover there what it is we react to, what it is that gets under our skin; we discover what is relevant to us. Those aspects of the theater and motion pictures that leave us cold will not serve the mirror function. The things we react to are mirroring some aspect of our inner nature and enable us to see it. The whole body of mythology serves that mirror function.

The mirror of Narcissus is an example of the risk lurking in the mirror. According to historians, Teiresias is supposed to have said, “Narcissus will live a long life, providing he never knows himself”—that is, providing he never looks into a mirror. But he did see his reflection in a pool and his life was cut short. This speaks of the danger that can come from seeing oneself prematurely, before one is able to assimilate it.

It is instructive to consider the etymology of the word mirror. It derives from the Latin miror, mirare, “to wonder at, to be astonished,” and therefore is cognate with such words as miracle and admire. The capacity to be amazed is connected to reflective consciousness. The Latin word for mirror is speculum, from specio, to look at or see. From that we have such words as speculate and spectacles; various words associated with “scope,” such as telescope and microscope, also come from the same root.

The mirror is an interesting image in folklore. According to primitive thinking, the reflection in a mirror is actually one’s soul. There is thus something uncanny about mirrors that accounts for the superstition that breaking one brings bad luck. Gazing into the mirror was not without risk, since one’s soul might be snatched away while the image was there. And covering mirrors after the death of a person was often practiced to prevent the ghost of the departed one from coming back through the glass or from dragging one into it. The mirror, in other words, signified the threshold between this world and the other world; Alice crossed this threshold in Through the Looking Glass when she stepped into the mirror and passed over to the other side, into the unconscious. Divination by mirrors was not uncommon, giving rise to the original meaning of the term speculate: to peer into a crystal ball or mirror in order to see into the future was to speculate.

Mirror symbolism and imagery can be seen from two standpoints: one is the collective function of the culture that we have just been discussing, and the other is the individual process of psychological development, and specifically the process of psychotherapy. A clear parallel can be drawn between the process of development that takes place in the personal analysis of the individual and the process of cultural development that has occurred in the history of the race. They are fundamentally of the same nature, one being the microcosm of the other. Just as the cultural history of humankind requires that there be memory, a past and knowledge of that past, and a consequent sense of continuity, so in personal psychotherapy we start out with a history of the individual’s past. One cannot exist as an aware, conscious being without remembering where one has come from, and what one has been. So a first procedure is to activate and stimulate the memory. As Santayana is supposed to have remarked about history in general, “He who does not remember the past is condemned to repeat it.” That observation is certainly true of the individual: all those repressed experiences that have been blocked from one’s individual memory, for whatever reason, will unfailingly be repeated again and again on an unconscious level until they are recollected and assimilated.

Then in psychotherapy we examine dreams. Dreams are the mirror that the unconscious throws up to us. The images we see in dreams are the reflections of our current state of being, and without those dreams we would have no way to perceive what we are. Dreams serve something of the same purpose for the individual that cultural forms, art, and literature serve for the collective. Individuals can also become their own artists and start painting their inner states or drawing them, or writing poems about them, thereby providing themselves with mirror images to enable themselves to see what they are. Active imagination serves the same mirror purpose.

The mirror function plays an important role in the therapist-patient relationship, which is one of the reasons that the relationship is so essential. Individuation does not proceed in a vacuum, because one needs not only an inner mirror but an outer one. We discover what we are to a significant extent by observing the effects we have on another; each of us serves a mirror purpose for the other, providing by our reactions, objective clues by which the other can increase his self-knowledge.

An impressive description of the significance of the mirror phenomenon is to be found in Schopenhauer, who in many respects can be regarded as the father of depth psychology. This passage is from The World as Will and Representation:

[It is] indeed wonderful to see how man, besides his life in the concrete, always lives a second life in the abstract. In the former he is abandoned to all the storms of reality and to the influence of the present; he must struggle, suffer and die like the animal. But his life in the abstract, as it stands before his rational consciousness, is the calm reflection of his life in the concrete, and of the world in which he lives. . . . Here, in the sphere of calm deliberation, what previously possessed him completely and moved him intensely appears to him cold, colorless and, for the moment, foreign and strange; he is a mere spectator [mirror-looker] and observer. In respect of this withdrawal into reflection, he is like an actor who has played his part in one scene, and takes his place in the audience until he must appear again. In the audience he quietly looks on at whatever may happen, even though it be the preparation of his own death (in the play); but then he again goes on stage and acts and suffers as he must.10

Psychologically speaking, what Schopenhauer is referring to is the ability to turn an unconscious complex, which possesses one, into an object of observation and knowledge. We could extend the analogy further and say that gaining such objectivity is really like struggling and suffering in the arena and then suddenly being transported from the arena to the spectator stand. That is what having a mirror is like. Being in the grip of the Medusan level of reality is transformed into the capacity to step aside and comprehend what one is dealing with from a distance. That is the basic requirement for developing consciousness.

a. At a superficial level, the image recalls Jesus’ washing the disciples’ feet. But the Biblical image belongs to a higher level of ego development and thus has a different meaning. The archaic Greek image applies to an earlier stage of ego development. The whole system of Christian virtues and the negation of the will is not really suitable for the young. One has to have something to sacrifice before giving up one’s egocentricity means anything. It can often happen that the task of developing a sturdy, aggressive ego is bypassed by taking on those so-called self-sacrificial virtues prematurely, and then the life process is actually short-circuited rather than fulfilled.