THE ILIAD, the epic of the Trojan war, appears to have been considerably more popular in antiquity than was The Odyssey. When Alexander the Great took a copy of Homer on his military campaigns, it was The Iliad that lay in his knapsack and at his bedside table, and this may stem from the fact that the Trojan War and The Iliad are primarily stories of the first half of life and its psychological issues.

The prologue to the war is evocative psychologically. The conflict grew out of what is known as the Judgment of Paris. Eris, the goddess of discord, threw a tantalizing golden apple into the assembly of the gods and goddesses and on it was written “for the fairest.” Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite all claimed the designation, and it was decided that the cattleherd Paris, the young son of Priam, the Trojan king, would assume the task of deciding who was entitled to the apple—offering yet another example of the dictum attributed to the old philosopher from Ephesus, Heraclitus, who observed that “strife is the father of all things.” Eris stirred up strife, and out of the strife emerged the Trojan War and all its consequences.

Paris was a young innocent. Though he was of noble birth, he had been sent to the countryside as a cattleherd. He signifies the ego to whom nothing has yet happened. Then out of the blue, Hermes, the messenger of the gods, presented him with an impossible task of judgment—to decide which of the three divinely beautiful goddesses was the fairest and should win the prize. Each sought to bribe him. Hera offered him the lordship of Asia and infinite riches; Athena promised him constant victory and wisdom; Aphrodite offered him the most beautiful woman of all to be his own; in short, Hera offered him power, Athena wisdom, and Aphrodite beauty. Paris tried to get out of it. He wanted to divide the apple into three pieces, but that was disallowed. He was forced to make a decision and he chose Aphrodite. The result was that Hera and Athena, in their rage at being rejected, initiated the Trojan War.

This story reflects a requirement of ego development. At a certain stage of psychological growth, a decision must be made as to what will be the highest value of the unfolding life. It is inevitable that if one is to develop a certain area of competence, one must make such a choice, and that means rejecting certain other possibilities. The myth tells us that having made such a choice, the rejected possibilities linger resentfully in the unconscious and eventually start trouble. It is really a tragic requirement that such a choice must be made if life is to unfold. Jung has reproduced an alchemical picture in Psychology and Alchemy with the title “The Awakening of the Sleeping King Depicted as a Judgment of Paris.”1 Paris, with the three naked goddesses in competition beside him, stands by a king sleeping on the ground. Paris is touching the sleeping king with his wand to wake him up. As he makes his judgment as to which feminine value will be most important, he is simultaneously awakening the sleeping king, the power of inner authority that had previously been unconscious. We can extrapolate to say that it does not matter which decision is made. Some people will give beauty the first value and reject the others, some may choose wisdom and still others power, but there will be a Trojan War no matter which is chosen because the neglected ones will react. In the myth, Aphrodite fulfilled her promise by giving Helen to Paris, who then abducted her from the palace of her husband, Menelaus, and took her to Troy where he lived. Hera and Athena then aroused the Greeks to fetch her back.

It is worthwhile to linger a little over the image of Helen. She is the classic anima figure of Western civilization. Gilbert Murray writes about her in his book The Rise of the Greek Epic:

Think how the beauty of Helen has lived through the ages . . . it is now an immortal thing. And the main, though not of course the sole, source of the whole conception is certainly The Iliad. Yet in the whole Iliad there is practically not a word spoken in description of Helen . . . almost the whole of our knowledge of Helen’s beauty comes from a few lines in the third book, where Helen goes up to the wall of Troy to see the battle between Menelaus and Paris. “So speaking, the goddess put into her heart a longing for her husband of yore and her city and her father and mother. And straightaway she veiled herself with white linen, and went forth from her chamber shedding a great tear. . . .” The elders of Troy were seated on the wall, and when they saw Helen coming, “softly they spake to one another winged words: ‘Small wonder that the Trojans and the mailed Greeks should endure pain through many years for such a woman. Strangely like she is in face of some immortal spirit.’ ” That is all we know. Not one of the Homeric bards fell into the yawning trap of describing Helen, and making a catalogue of her features. She was veiled; she was weeping; and she was strangely like in face to some immortal spirit. And the old men, who strove for peace, could feel no anger at the war. . . . the weeping face of Helen [has behind it] not the imagination of one great poet, but the accumulated emotion, one may almost say, of the many successive generations who have heard and learned and themselves afresh recreated the old majesty and loveliness. They are like the watchwords of great causes for which men have fought and died; charged with power from the first to attract men’s love, but now through the infinite shining back of that love, grown to yet greater power. There is in them, as it were, the spiritual life blood of a people.2

That is a description of an archetypal image written in 1907—before the theory of archetypes had been elaborated. The image of Helen runs through much of the literature and mythology of the Western world. She appears in the myth of Simon Magus, a Gnostic redeemer, who found Helen in a brothel in Tyre. She was, according to the myth, the incarnation of the fallen Sophia, the fallen wisdom of God. Simon Magus retrieved her from the brothel and took her on his travels. He was the prototype of the Faust legend, and Helen is present in all the versions of that story. In Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragedy of Doctor Faustus, she enters after she has been summoned by Mephistopheles. Faustus exclaims:

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul, see where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell for heaven is in these lips

And all is dross that is not Helena.

I will be Paris and for love of thee

Instead of Troy shall Wittenberg be sacked.

I will combat with weak Menelaus

And wear thy colors on my plumed crest.

Yea, I will wound Achilles in the heel

And then return to Helen for a kiss.

O thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars!

Brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter

When he appeared to hapless Semele.

More lovely than the monarch of the sky

In wanton Arethusa’s azured arms

And none but thou shall be my paramour!3

Shortly, he had to pay the price and be consigned to hell. An ominous implication is already in the lines “brighter art thou than flaming Jupiter when he appeared to hapless Semele.” Semele was the mother of Dionysus, who insisted on seeing Zeus, or Jupiter, in his true form and was blasted to death by the sight. And that in effect is what happened to Faust. He took Helen for his own pleasure, and when an archetype is approached with such an attitude, it destroys.

The image of Helen runs throughout Goethe’s Faust as the basic motivation of the whole story. In part one Gretchen is a personal representation of Helen, and in part two Helen herself appears and at the very end takes on the final glorification of the eternal feminine. One can say that Goethe’s Faust completes The Iliad so far as the image of Helen is concerned because the anima is there redeemed and recognized as divine, which becomes evident in the final lines of part two. After Faust has arrived in heaven, these are the lines, as Louis MacNeice translates them:

All you tender penitents,

Gaze on her who saves you—

Thus you change your lineaments

And salvation laves you.

To her feet, each virtue crawl,

Let her will transcend us;

Virgin, Mother, Queen of all,

Goddess still befriend us!

All that is past of us

Was but reflected;

All that was lost in us

Here is corrected;

All indescribables

Here we descry;

Eternal womanhood

Leads us on high.4

This is the ultimate apotheosis of Helen through Western literature.

In The Iliad, eternal womanhood, at a more primitive level, leads men into a bloody battle. Jung has spoken of the anima image as the archetype of life, and its dynamism is to lead one into life, and often, as well, into painful, complicated, ambiguous situations.

Helen had a sister. According to the story, Helen was fathered by Zeus in the form of a swan, and her sister Clytemnestra came from a human father, Tyndareus. These sisters were married to brothers, Helen to Menelaus and Clytemnestra to Agamemnon. The bulk of the retribution for Helen’s abduction and all its consequences fell upon Agamemnon and Clytemnestra rather than upon Helen and Menelaus. Agamemnon and Clytemnestra represent the human level of the unfolding sequence, and Helen—and by contiguity with her, Menelaus—represent the archetypal or divine component, who are not touched. Menelaus and Helen returned home and lived on uneventfully. Agamemnon and Clytemnestra lived out the tragic dimension.

Helen was plucked out of her Mycenean palace and abruptly everything changed. Suddenly the anima was no longer safely ensconced in the familiar surroundings. Suddenly she disappeared, spirited away to Troy; hence, all Greece must be mobilized to bring her back. This situation could well be seen psychologically as an anima projection, in which the anima instead of being experienced internally is discovered elsewhere. The effect is to activate the ego to repossess her, Agamemnon as the leader of the Greek forces here signifying the ego. As this mobilization proceeded, even the heroes attempted to evade the draft. Odysseus for instance had been told by an oracle that if he went to Troy he would not get back for twenty years. When he heard that the recruiters were coming, he feigned madness. He was found plowing a field with an ass and an ox yoked together. The ruse was detected when his son was put in front of the plow and Odysseus veered away to prevent killing him, proving he was not mad. Psychologically, we might say that the difficult call to individuation cannot be avoided by such wiles because denial of it involves killing the child, the child symbolizing the future potentiality that will be destroyed if the task is not accepted.

The expedition assembled under the leadership of Agamemnon was preparing to set sail at Aulis when the wind suddenly began blowing in the wrong direction, as if the spirit was against them—the objective transpersonal spirit. A soothsayer informed them that Artemis had been offended and demanded the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter Iphigeneia, and after strenuous attempts to evade such a crime, she was given over for sacrifice.

Here we are told that for a masculine enterprise of the magnitude of the campaign against Troy, a young feminine element of the psyche must be sacrificed. This corresponds to a certain stage of psychological development in young men in which the feminine component, and feminine values, must be depreciated if the masculine principle is to find the energy to function. At this stage, to be buffeted by two contrary values operating simultaneously is immobilizing, like contrary winds; one can’t get out of the original harbor that way. It generally happens on a purely automatic, instinctive basis that the young man at a certain level belittles womanhood and femininity. As the myth tells us, doing so is a crime, a grave crime that brings grave consequences, which the myth reveals as the story later unfolds. It works in the short run, the first half of life, but not later on when the man has to meet the consequences of his earlier decisions.

The image of Iphigeneia can also operate in the psyche of the woman, but it is damaging. An example of this was a woman who in childhood had been the butt of jokes and mistreatment from the men in her environment, a kind of scapegoat of the masculine ego to maintain its own illusory sense of importance. The result was that, in a certain sense, she became identified with Iphigeneia and her image. She once dreamed that her portrait was being painted. Intended to express her inner soul, it bore the title “Iphigeneia Looking Out to Sea.”

When Agamemnon arrived home ten years later, he was forced to meet the consequences of the sacrifice that had enabled him to go to Troy. Clytemnestra was waiting to take revenge on him for it, and in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon it is made quite clear that the basic sin for which he must die is what the Greeks called hybris. Upon his arrival his wife sought to have him walk on a lavish purple cloth that had been spread out from his chariot to the palace. Agamemnon protested in these words:

Know, that the praise which honor bids us crave,

Must come from others’ lips, not from our own:

See too that not in fashion feminine

Thou make a warrior’s pathway delicate;

Not unto me, as to some Eastern lord,

Bowing thyself to earth, make homage loud.

Strew not this purple that shall make each step

An arrogance; such pomp beseems the gods,

Not me. A mortal man to set his foot

On these rich dyes? I hold such pride in fear,

And bid thee honor me as man, not god.5

But despite those protests he succumbed and trod the purple into the palace and to his death.

The Greeks had great fear of hybris. In its original usage the term meant a kind of wanton violence or passion arising from pride—in psychological terms, inflation. It is the human arrogance that appropriates to man what belongs to the gods, or in psychological terms appropriates to the ego what belongs to the transpersonal level of the psyche. Hybris is the transcending of proper human limits, and Gilbert Murray has this to say about it:

There are unseen barriers which a man who has reverence [the Greek word is aidos] in him does not wish to pass. Hybris passes them all. Hybris does not see that the poor man or the exile has come from Zeus [as Philemon and Baucis could see]: Hybris is the insolence of irreverence: the brutality of strength. . . . It is a sin of the strong and proud. It is born of . . . satiety—of “being too well off;” it spurns the weak and helpless out of its path. . . . [It is] the typical sin condemned by early Greece.6

If we read the Agamemnon story as a typical and more or less inevitable process in psychological development, it means that the experience of hybris is more or less unavoidable. As other material indicates, just the presumption for an ego to come into existence at all and to claim itself as a separate center of conscious being is replete with hybris, and this psychological fact then links with the imagery of original sin, which is a symbolic example of hybris.

It appears that the forerunner of The Iliad as we know it was originally a poem called “The Wrath of Achilles,” and the opening of The Iliad indicates that Achilles is really the central figure. It begins this way:

The wrath of Peleus’ son [Achilles], the direful spring

Of all the Grecian woes, O Goddess, sing!

That wrath which hurled to Pluto’s gloomy reign

The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain;

Whose limbs unburied on the naked shore

Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore.

Since great Achilles and Atrides strove,

Such was the sovereign doom and such the will of Jove.7

In these opening lines it almost sounds as though Achilles’ wrath caused the war in the first place, but what it did cause was a prolongation of that war, resulting in far more casualties than would otherwise have been the case. Achilles was an invulnerable hero, or almost so, a gift of his mother Thetis, who following his birth dipped him in the River Styx, a process that protected him except for the place on his heel where she held on to him.

How do we interpret that psychologically? It can be said that Achilles represents the life and fate of the psychic factor that is invulnerable by virtue of having experienced total maternal love and acceptance in childhood. Achilles is a mother’s boy in the best sense of that term and there is a lot of psychological evidence to indicate that total loving acceptance on the part of the mother does indeed convey a kind of psychological invulnerability, generating self-assurance and confidence in one’s own worth that is built in; one is dipped in invulnerability. Freud was an example of the Achilles experience: he was the firstborn and favorite son of his adoring mother, who repeatedly told him about predictions of his greatness. In later life Freud wrote, “A man who has been the indisputable favorite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror, that confidence of success that often induces real success.”8 That sounds all very enviable, of course, but there is still the heel, because whatever is conveyed by a process other than one’s own must have some defect. To become whole, one cannot have anything given entirely from the outside; indeed, only a monster would be totally invulnerable. Rather it is Achilles’ vulnerability that saves his humanity, so to speak. As The Iliad proceeds, it becomes clear that Achilles’ vulnerability, psychologically speaking, lay in his sulky resentments. At the outset of the war, Agamemnon was obliged to give up a prize of battle, his favorite concubine, whom he was required by the gods to return to her father, leaving him in the intolerable position of being womanless when all his men enjoyed such company. He solved the problem by appropriating Achilles’ concubine, stirring Achilles to such resentment that he refused to participate any further in the war and retreated to sulk in his tent.

Here we have a second case, on another level, of the loss of a woman influencing the war, which had been set off by the loss of Helen. Achilles’ vulnerability came from his inability to accept the objective authority of others. Agamemnon makes that point when he says, speaking of Achilles:

. . . that imperious, that unconquered soul,

No laws can limit, no respect control.

Before his pride must his superiors fall,

His word the law, and he the lord of all?

Him must our hosts, our chiefs, our self obey?

What king can bear a rival in his sway?9

In his refusal to recognize the authority of Agamemnon, Achilles came to grief on the power problem. Since he could not oppose Agamemnon on realistic grounds, he opposed him by what we would call an anima mood, a sulky, resentful withdrawal. And this indeed fits the psychology of a mother’s favorite, inasmuch as he becomes accustomed to having everything he wants, making it difficult, if not impossible, for him to subordinate his world to the objective authority of others. Achilles’ response, in effect, was to subvert the whole Greek enterprise by personalizing its purposes.

Achilles eventually lost his life by being pierced in his one weak spot, but The Iliad does not go into that. The Iliad as a work of art has its own beginning and end, and it ends differently; it ends in a resolution. Although it is a frightfully brutal work, what starts out as the wrath of Achilles is resolved in a reconciliation between Achilles and Priam. Achilles finally returned to the fighting through another personal motivation: his closest friend, Patroclus, was killed. So his wrath against Agamemnon was redirected to Hector, who had killed Patroclus. Hector, the foremost champion of the Trojans and son of Priam, the king, was slaughtered and his body was ignominiously dealt with by the vengeful Achilles. But aged Priam picked his way through the enemy lines, with the help of Hermes, and arrived as a suppliant at Achilles’ tent.

Priam begged Achilles to be allowed to ransom back the body of his son, something that meant a great deal in those times. These are the concluding lines, in effect the end of The Iliad and the reconciliation. Old Priam is talking to Achilles and telling him why he has come:

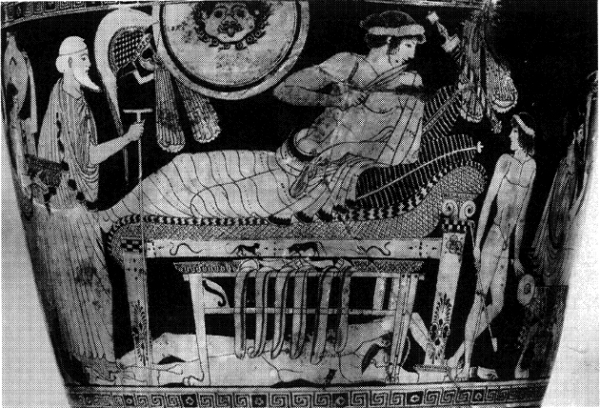

FIG. 20. Old King Priam approaches Achilles to ransom the body of his son, Hector, that lies beneath Achilles’ couch. (Detail of an Attic skyphos, c. 480 BC. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.)

“For him [Hector], through hostile camps I bent my way,

For him thus prostrate at thy feet I lay;

Large gifts, proportioned to thy wrath, I bear;

Oh hear the wretched and the gods revere!

Think of thy father and this face behold!

See him in me, as helpless and as old,

Though not so wretched: there he yields to me,

The first of men in sovereign misery.

Thus forced to kneel, thus groveling to embrace,

The scourge and ruin of my realm and race;

Suppliant my children’s murderer to implore,

And kiss those hands yet reeking with their gore!”

These words soft pity in the chief inspire,

Touched with the dear remembrance of his sire.

Then with his hand (as prostrate still he lay),

The old man’s cheek he gently turned away.

Now each by turns indulged the gush of woe

And now the mingled tides together flow:

This low on earth, that, gently bending over;

A father one, and one a son, deplore:

But great Achilles different passions rend,

And now his sire he mourns, and now his friend.

The infectious softness through the heroes ran;

One universal, solemn shower began;

They bore as heroes, but they felt as man.

Satiate at length with unavailing woes,

From the high throne divine Achilles rose;

The reverend monarch by the hand he raised;

On his white beard and form majestic gazed,

Not unrelenting; then serene began

With words to soothe the miserable man.

“Alas! what weight of anguish hast thou known?

Unhappy prince! Thus guardless and alone

To pass through foes and thus undaunted face

The man whose fury has destroyed thy race?

Heaven sure has armed thee with a heart of steel,

A strength proportioned to the woes you feel.

Rise then: let reason mitigate our care:

To mourn avails not: man is born to bear.

Such is, alas! the gods’ severe decree:

They only are blessed and only free.”10

This is the resolution, in which their mutual humanity was experienced in their mutual flow of tears and their realization that they were in the same relation to the gods. It was a coniunctio, a coming together of opposites. Starting out with a war between opposites, the sad reconciliation was the conclusion.