AMONG THE most remarkable phenomena of the ancient world were the Eleusinian mysteries, which were based on the myth of De-meter and her daughter Persephone. The story relates that Demeter and Persephone were strolling in a meadow where Persephone, who was picking flowers, plucked a narcissus, which was held to be the gateway to the Underworld. The earth sprang open and Hades emerged and carried her off to his realm. Demeter, disconsolate, wandered the earth seeking her. During her absence nothing grew; no seeds sprouted, no leaves came out, no fruit was borne. Everything was sterile and it became evident that mankind would be destroyed if Persephone did not return, so Zeus ordered it. However, a complication arose. She had eaten seven pomegranate seeds while in Hades’ kingdom and that committed her to the Underworld; she had a stake in it or it had a stake in her. Finally a compromise was devised under which she was to spend six months of the year above ground and six months in the Underworld as the queen of Hades. Meanwhile, during her wanderings, Demeter had stopped at the little village of Eleusis, twelve miles south of Athens, where she was given hospitality by some kindly people, and in return, she had taught her mysteries to the Eleusinians. Such are the bare bones of the myth.

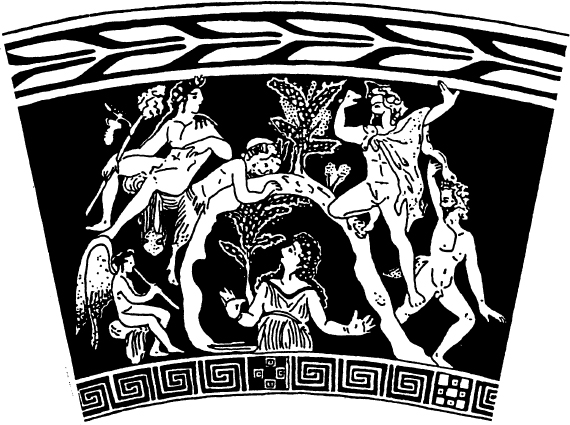

FIG. 26. Persephone returns from beneath the ground, renewing life on earth. She is greeted by Dionysus, Pan, and dancing satyrs; Eros plays the pipes; plants and flowers spring forth. (Transcription by J. Wheelock after a 4th-century BC Attic krater, now lost.)

In its most apparent psychological meaning the myth describes a stage of feminine development, the emergence from psychic maidenhood by way of an initial encounter with the masculine. Wrested from her innocent state of daughter and partner of Demeter and plunged into the darkness under the earth, Persephone was suddenly faced with the breakup of the comfortable all-feminine matriarchal condition (as Neumann uses that term).1 It was torn apart by the appearance of the new masculine principle, represented by Hades. This particular image comes up not uncommonly in young women’s dreams. The dreamer of one such dream was in her early twenties:

I’m in a sunny field on the crest of a hill picking flowers for the garland or wreath that will crown my head, for today is my wedding day. There is a female friend with me whom I can’t identify. The flowers are exquisitely beautiful, of varieties I’ve never seen before. I’m very happy. The wedding guests who had gathered here with me have dispersed for the day and will return later for the ceremony. The groom had also gone. I don’t know who he was. My mother had fixed my hair by putting it up with flowers but it was all wrong and I became upset and took it down and placed the garland of flowers atop my head. I felt angry that the wedding guests had stayed away for so long as it was already growing late. We gathered in the place where the marriage would take place. This place was aglow with a strange unearthly light, surrounded by a brooding luminous darkness, like the painting of Christ on the cross at his death, when the whole earth quakes and trembles at the meaning of the event.

It should be noted that the unconscious does not duplicate the ancient myth but gives it a Christian twist, with Christian imagery, yet including the original elements of the darkness and the earthquake that is in the offing as the marriage is about to be performed. This image, even to the equation of marriage and death, appears frequently, for example in the story of Amor and Psyche. When the ego of the young woman opens itself to receive the masculine principle for the first time, the whole unconscious seems to open up and this is experienced as a kind of death of the ego, since it involves the loss of the old way as part of the transformation. Dreams of this sort illustrate why purely sexual or even interpersonal interpretations of events such as puberty are inadequate to the psychic realities. One is dealing with another level entirely that is revealed only by such archetypal images as the emergence of Hades from the depths of the earth and, in the case of this modern dream, as the darkness and earthquakes accompanying the crucifixion of Christ.

Here we are looking at the myth of Demeter and Persephone rather specifically and as relevant chiefly to woman’s psychology. On a more general level, it is to be read as a death and rebirth mystery, and thus applicable to both men and women, and it was in this wider aspect that it became the foundation for the Eleusinian mysteries, which existed for twelve hundred years. Sworn to strictest secrecy—and the secret was kept—multitudes of people were initiated at Eleusis, including some of the most prominent people of antiquity, Augustus and Marcus Aurelius among them. The rituals were divided into two different categories called the lesser mysteries and the greater mysteries; the former were performed at Agrae, a suburb of Athens, in February, approximately the time that Persephone starts coming to life in the greening of spring; and the latter were celebrated at Eleusis in September, at the time when Persephone is descending into the Underworld.

Thus we have the curious situation that the emergence, the rebirth, was observed as the lesser ritual and the descent as the greater. We may look at the double aspect of the mysteries as corresponding to the two aspects of the psyche as we understand it, what Jung has labeled the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious; dealing with the first we know to be a lesser task, and dealing with the second, a greater task. The lesser mysteries at Agrae consisted largely in purification and instruction, while the greater mysteries, which required that one first go through the lesser ceremonies, lasted about nine days. Further purifications and sacrifices ended in what was called the epopteia, a final visionary experience.

A great deal of scholarly effort has been expended seeking to determine what happened in the rituals, since no participant’s description has ever come to light. There is reason to believe that some form of sacred marriage was symbolized; some kind of reenactment of Demeter’s wanderings, searching for Persephone, and reunion with her was performed, and some form of imagery was presented concerning the birth of the divine child, perhaps symbolized by an ear of wheat. It is known that at the beginning of the greater ceremonies at Eleusis, a solemn warning was issued that those seeking initiation must speak Greek and have pure hands and pure hearts, the same requirement of purity as in Orphism, and indeed it is probable that the Eleusinian mysteries were considerably influenced by Orphic factors. The effects of the initiation seem to have been a psychological regeneration and an experience of renewed life, a sense of meaning and hope. This is most succinctly expressed by suggesting, as Kerényi puts it, that the ultimate purpose of the mysteries was to convey the beatific vision.2 This connects the Mysteries, like Orphic ritual, with Greek philosophy, which also was considered to have as its ultimate goal the beatific vision.

In the Phaedrus, speaking of man’s memories of his previous (prenatal) existence, Plato says, “He who employs aright these memories is ever being initiated into perfect mysteries and alone becomes truly perfect.” The Greek word for “perfect” (teleios) also means “initiate,” so another translation could be “becomes a true initiate, the truly complete one.”

But, as he forgets earthly interests and is rapt in the divine, the vulgar deem him mad, and rebuke him; they do not see that he is inspired. . . . For, as has already been said, every soul of man has in the way of nature beheld true being and this was the condition of her passing into the form of man. But all souls do not easily recall the things of the other world; they may have seen them for a short time only, or they may have been unfortunate in their earthly lot, and having had their hearts turned to unrighteousness through some corrupting influence, they may have lost the memory of the holy things which once they saw. Few only retain an adequate remembrance of them; and they, when they behold here any image of that other world, are rapt in amazement; but they are ignorant of what this rapture means, because they do not clearly perceive. For there is no light of justice or temperance or any of the higher ideas which are precious to souls in the earthly copies of them: they are seen through a glass dimly; and there are few who going to the images, behold in them the realities, and these only with difficulty. There was a time when with the rest of the happy band they saw beauty shining in brightness,—we philosophers following in the train of Zeus, others in company with other gods; and then we beheld the beatific vision and were initiated into a mystery which may be truly called most blessed, celebrated by us in our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come, when we were admitted to the sight of apparitions innocent and simple and calm and happy, which we beheld shining in pure light. . . . 3

Plato thus specifically identifies the philosophers with those initiated into the mysteries. This particular passage has been interpreted as indicating that apparitions were generated and displayed in the Eleusinian mysteries, assuming that Plato knew about the mysteries and is alluding to what happened in them in a veiled way. While that cannot be proved or disproved, the passage nevertheless forms a link between the two cultural forms—the mysteries and the philosophical systems, and is useful as one attempts to trace the basic archetypal images as they manifest themselves in progressively more differentiated forms through the history of Western culture. From the elemental myths, into their religious and ritual expressions such as Orphism, into the philosophical manifestations, and then branching out into such diverse areas as alchemy, Christian theology, and modern depth psychology, the thread can be followed.

The basic effect of the mysteries seemed to be that they reconciled the participants to life and in that sense were redeeming. For instance, in the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter,” we find: “Happy is he among men on earth who has seen these mysteries; but he who is uninitiate and who has no part in them, never has lot of like good things once he is dead, down in the darkness and gloom.”4 Although the sense of redemption is projected into the afterworld, that is nonetheless the nature of the actual experience. It seems that the initiation into the mysteries conveyed a new awareness of the nature of life—some kind of insight into the transcendent dimension of being that was primarily reassuring and generated hope. Hope is repeatedly spoken of as one of the effects of the initiation; it was one of the consequences of the beatific vision.

These themes come up in one of a series of dreams of a man who was to die several months later:

I was with several companions in a Daliesque landscape where things seemed either imprisoned or out of control. There were fires all about coming out of the ground and about to engulf the place. By a group effort, we managed to control the fires and restrict them to their proper place. In the same landscape, we found a woman lying on her back on a rock. The front side of her body was flesh, but the back of her head and body was part of the living rock on which she lay. She had a dazzling smile, almost beatific. It seemed to accept her plight. The controlling of the fire seemed to have caused a metamorphosis of some kind and began a loosening of the rock at her back so that we were finally able to lift her off. Although she was still partly stone, she did not seem too heavy and the change was continuing. We knew that she would be whole again.

What makes the dream relevant in this context is that the setting, and the fires in particular, reminded the dreamer of the fire that was said to accompany Hades when he broke out of the earth to capture Persephone. The dreamer had once visited Eleusis and had been shown the spot where Hades was supposed to have emerged. That was his first association to the dream. Kerényi5 has demonstrated that sacred fire was one of the features of the Eleusinian mysteries and of course the beatific smile of the woman is an allusion to the beatific vision. The dream carried a sense of reassurance with it.

We can best relate to these mysteries, perhaps, by taking a few examples of what can be considered their modern counterparts. We have no collective or ceremonial equivalent to the Eleusinian mysteries today, but we can find in psychotherapy and in literature and biography examples that are analogous to what presumably happened at Eleusis. Here is a dream that can be taken as a modern equivalent of the beatific vision. It is a dream of J. B. Priestley’s, quoted in his book Rain Upon Godshill and reproduced in Gerhard Adler’s Studies in Analytical Psychology:

I dreamt I was standing at the top of a very high tower, alone, looking down upon myriads of birds all flying in one direction; every kind of bird was there, all the birds in the world. It was a noble sight, this vast aerial river of birds. But now in some mysterious fashion the gear was changed, and time speeded up, so that I saw generations of birds, watched them break their shells, flutter into life, mate, weaken, falter, and die. Wings grew only to crumble; bodies were sleek and then, in a flash, bled and shrivelled; and death struck everywhere at every second. What was the use of all this blind struggle towards life, this eager trying of wings, this hurried mating, this flight and surge, all this gigantic meaningless biological effort? As I stared down, seeming to see every creature’s ignoble little history almost at a glance, I felt sick at heart. It would be better if not one of them, if not one of us all, had been born, if the struggle ceased for ever. I stood on my tower, still alone, desperately unhappy. But now the gear was changed again, and time went faster still, and it was rushing by at such a rate, that the birds could not show any movement, but were like an enormous plain sown with feathers. But along this plain, flickering through the bodies themselves, there now passed a sort of white flame, trembling, dancing, then hurrying on; and as soon as I saw it I knew that this white flame was life itself, the very quintessence of being; and then it came to me, in a rocket-burst of ecstasy, that nothing mattered, nothing could ever matter, because nothing else was real, but this quivering and hurrying lambency of being. Birds, men, or creatures not yet shaped and colored, all were of no account except so far as this flame of life travelled through them. It left nothing to mourn over behind it; what I had thought was tragedy was mere emptiness or a shadow show; for now all real feeling was caught and purified and danced on ecstatically with the white flame of life.6

Another example comes from Jung’s visions and their aftermath, which appear to be about the same level of experience as the ancient material itself. During Jung’s long weeks of convalescence after the basileus of Kos in the form of his physician had brought him back to life, he had experiences that are modern analogies of the beatific vision of the Eleusinian mysteries:

During those weeks I lived in a strange rhythm. By day I was usually depressed. I felt weak and wretched, and scarcely dared to stir. Gloomily, I thought, “Now I must go back to this drab world.” Toward evening I would fall asleep, and my sleep would last until about midnight. Then I would come to myself and lie awake for about an hour, but in an utterly transformed state. It was as if I were in ecstasy. I felt as though I were floating in space, as though I were safe in the womb of the universe—in a tremendous void, but filled with the highest possible feeling of happiness. “This is eternal bliss,” I thought. “This cannot be described; it is far too wonderful!” . . . [I seemed to be] in the Pardes Rimmonim, the garden of pomegranates [a note in the text tells us that this is the title of an old Cabbalistic tract; it is the place where Malchuth and Tifereth, two aspects of the deity, appear], and the wedding of Tifereth with Malchuth was taking place. Or else I was Rabbi Simon ben Jochai, whose wedding in the afterlife was being celebrated. It was the mystic marriage as it appears in the Cabbalistic tradition. I cannot tell you how wonderful it was. I could only think continually, “Now this is the garden of pomegranates! Now this is the marriage of Malchuth with Tifereth!” . . . And my beatitude was that of a blissful wedding.

Gradually the garden of pomegranates faded away and changed. There followed the Marriage of the Lamb, in a Jerusalem festively bedecked. I cannot describe what it was like in detail. These were ineffable states of joy. Angels were present, and light. I myself was the “Marriage of the Lamb.”

That, too, vanished, and there came a new image, the last vision. I walked up a wide valley to the end, where a gentle chain of hills began. The valley ended in a classical amphitheater. It was magnificently situated in the green landscape. And there, in this theater, the hierosgamos [the sacred wedding] was being celebrated. Men and women dancers came on stage, and upon a flower-decked couch All-father Zeus and Hera consummated the mystic marriage, as it is described in the Iliad.

All these experiences were glorious. Night after night I floated in a state of purest bliss, “thronged round with images of all creation. . . .” It is impossible to convey the beauty and intensity of emotion during those visions. They were the most tremendous things I have ever experienced.7

Finally, there is Dante’s vision, with which he concludes The Divine Comedy, and which is parallel to Jung’s and to what may have been the beatific vision experienced by at least a few in the Eleusinian mysteries:

O Light Supreme, that art so far exalted

Above our mortal ken! Lend to my mind

A little part of what Thou didst appear,

And grant sufficient power unto my tongue

That it may leave for races yet unborn,

A single spark of Thy almighty flame!

For if Thou wilt come back to my remembrance,

That I may sing Thy glory in these lines,

The more Thy victory will be explained.

I think the keenness of the living ray

That I withstood would have bewildered me,

If once my eyes had turned aside from it.

And I recall that for that very reason

I was emboldened to endure so much,

Until my gaze was joined unto His good.

Abundant grace, by which I could presume

To fix my eyes upon the Eternal Light,

Sufficiently to see the whole of it!

I saw that in its depths there are enclosed

Bound up with love in one eternal book,

The scattered leaves of all the universe—

Substance, and accidents, and their relations,

As though together fused in such a way

That what I speak of is a single light.

The universal form of this commingling,

I think I saw, for when I tell of it,

I feel that I rejoice so much the more. . . .

For within the substance, deep and radiant,

Of that Exalted Light, I saw three rings

Of one dimension, yet of triple hue.

One seemed to be reflected by the next,

As Iris is by Iris; and the third

Seemed fire, shed forth equally by both.

How powerless is speech—how weak compared

To my conception, which itself is trifling

Beside the mighty vision that I saw!

Oh Light Eternal, in Thyself contained!

Thou only know’st Thyself and in Thyself

Both known and knowing, smilest on Thyself!

That very circle which appeared in Thee,

Conceived as but reflection of a light,

When I had gazed on it awhile, now seemed

To bear the image of the human face

Within itself, of its own coloring—

Wherefore my sight was wholly fixed on it.

Like a geometer, who will attempt

With all his power and mind to square the circle,

Yet cannot find the principle he needs:

Just so was I, at that phenomenon.

I wished to see how image joined to ring,

And how the one found place within the other.

Too feeble for such flights were my own wings;

But by a lightning flash my mind was struck—

And thus came the fulfillment of my wish.

My power now failed that phantasy sublime:

My will and my desire were both revolved,

As is a wheel in even motion driven

By Love, which moves the sun and other stars.8