Where and when Great Shearwater is a summer visitor from its breeding islands in the South Atlantic (principally Tristan da Cunha) reaching British and Irish waters from July to October, with most in August to September; although numerous offshore, it is rarely seen from land, even during strong westerly gales. The best way to see them is by joining an organised Atlantic pelagic trip, when they can often be found following trawlers. Cory’s Shearwater occurs from April to September, with most in July and August, principally off Cornwall and s. Ireland. Annual totals vary considerably: more than 5,000 in 1998 but just 87 in 2007.

Size and shape About the size of Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus, Cory’s is the largest European shearwater, being slightly larger than Great with slightly longer wings in direct comparison.

Plumage Rather featureless, leading to its epithet ‘the Garden Warbler Sylvia borin of the oceans’. Brown above and white below with a narrow brown border to the underwings. The two main differences from Great are the dusky-grey sides to the head, which gradually merge into the white underparts, and the pale yellow bill, which in good light is obvious at considerable distances. Other features include an inconspicuous narrow white horseshoe-shaped uppertail-covert patch, immediately in front of the tail, and it can also show a faint dark ‘W’ across the upperwings, a result of slightly darker primaries and rear wing-coverts.

Flight Much more distinctive is its shape and flight. It flies on distinctly down-bowed wings with the carpals pushed forward and the primaries angled backwards. It has a slow, lazy and rather languid flight, rising up over the waves then gliding low over the surface, which it tends to hug, rather than shearing from side to side.

There is a single accepted record of Scopoli’s Shearwater, which replaces Cory’s in the Mediterranean. This species, split from Cory’s in 2012, may be overlooked. In direct comparison it is smaller and slighter than Cory’s with a slimmer bill; most importantly, the white of the underwing intrudes extensively into the primaries (see Fisher & Flood 2010).

Plumage Although similar to Cory’s in size and general appearance, Great has much more definite plumage characters that are easily seen in a reasonable view. Most distinctive is a somewhat skua-like head pattern with a well-defined black cap that appears tipped forward, contrasting sharply with the gleaming white face and collar, the latter extending up around the sides of the neck. Unlike Cory’s, it has a black bill. The underparts show a dark shoulder patch, recalling the ‘breast peg’ of non-breeding Black Tern Chlidonias niger; there is a narrow but variable diagonal black bar across the underwing-coverts and a small black belly patch – or ‘oil stain’ – that may be apparent in closer views. Like Cory’s, it has a white uppertail-covert crescent but this tends to stand out more strongly against the darker brown upperparts and the blacker tail. Note that these plumage differences are strongly influenced by the light. In good light, Great looks more ‘two-toned’ than Cory’s, the blacker outer wings contrasting more strongly with the browner inner wings. This effect may be further emphasised by the fact that the rear of the wing may look pale as a consequence of the light reflecting off pale wing-covert fringing. However, Great’s upperwings look more uniform in dull light and, if seen against the sun, the differences between the two species become less obvious.

Flight Great does not have Cory’s lazy flight; although it too flies on bowed wings, it instead has a stiffer-winged action that is more reminiscent of smaller shearwaters, such as Manx Puffinus puffinus. It has slightly quicker wingbeats than Cory’s with four to five flaps followed by a glide and, like Manx, it tends to shear more over the surface of the water. However, variation exists depending on what the birds are doing (e.g. feeding or purposefully migrating) and on the prevailing weather conditions, particularly wind strength.

Pitfalls Undoubtedly the greatest identification problems occur not with separating them from each other, but with separating them from other species. Being a rather featureless shearwater, Cory’s is a notorious ‘beginner’s bird’ and the less experienced seawatcher is urged to exercise caution and to claim only those individuals that are seen well. Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis provides the greatest pitfall, particularly when silhouetted at long range or in inclement weather. In these circumstances, Fulmar’s characteristic white head and pale primary bases may be impossible to detect, while ‘blue-phase’ Fulmars would not show these features anyway. In strong winds, Fulmars also bound in high arcs over the waves, so pay attention to shape and flight: Fulmars have fat, cigar-shaped bodies and fly with a flap-flap-glide on stiff but slightly bowed wings, interspersed with periods of banking and gliding. Another pitfall is provided by Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus, which is slightly larger and bulkier than Manx. Paler examples are brown above and dusky-white below but their shape is more similar to Manx (see Manx, Balearic and Sooty Shearwaters) like Manx, they also fly with rapid, shallow, stiff-winged strokes (but tend to shear slightly less, producing a more direct flight). The underwing is dusky-white with a brownish tip, trailing edge and axillaries. At close range, the small bill is blackish. Silhouetted Gannets Morus bassanus can also be confused, but are easily eliminated by their long, narrow, sharply pointed wings, long head and bill profile, and long, pointed tail. Immature Herring L. argentatus and Lesser Black-backed Gulls also need to be considered, bearing in mind the rather languid, gull-like flight of Cory’s.

Reference Fisher & Flood (2010).

Where and when Manx Shearwater is an abundant breeding species at selected sites in n. and w. Britain (and Ireland). It is likely to be seen off all coasts, mainly from March to October. Balearic Shearwater is mainly a summer visitor in varying numbers, traditionally encountered off s. England in July and August. Listed as Critically Endangered but, paradoxically, it has recently increased in the English Channel, apparently as a result of its non-breeding range shifting northwards in response to global warming. It is now also seen more widely throughout the year, particularly from Dorset to Cornwall but also penetrating the Irish and North Seas, with a few even reaching Scotland. Sooty Shearwater is usually an uncommon but widespread summer visitor from the Southern Hemisphere, reaching British and Irish waters from July to October (large numbers may be seen off w. Ireland after autumn gales).

Easily identified: strikingly black above and white below, the demarcation being sharply defined. It flies with rapid, stiff-winged strokes, followed by a period of shearing, gliding and banking low over the waves, alternately revealing the upperparts and then the underparts. The long wings and shearing flight instantly separate it from auks, which can appear similarly patterned at a distance.

Size and structure Although similar to Manx in size and structure, it averages c. 10% larger. It is also distinctly heavier and thicker-set, particularly about the head and neck, creating a front-heavy appearance. These differences are best appreciated in direct comparison with Manx, when Balearic appears positively thickset and stocky. It is also shorter-tailed but, unlike Manx, the feet project quite noticeably beyond the tail. The wings are proportionately slightly shorter than Manx, contributing to a slightly flappier flight with an upward lift followed by a low glide over the water. Flight differences are otherwise subtle, although it tends to shear slightly less than Manx, producing a slightly more direct flight.

Plumage Surprisingly variable but, in direct comparison with the smart and contrasting black-and-white Manx, most Balearics appear brown and rather dusky (note, however, that in bright light Manx’s black upperparts can momentarily appear very brown at certain angles). The head, flanks and undertail-coverts are brown, merging with the rest of the underparts, which are a rather dusky whitish. The underwings too are dusky (with a dark trailing edge). Brown ‘armpits’ (white on Manx) and a brown band across the base of the underwings may also be noticeable. Late summer adults may be worn and bleached, some showing a pale collar around the back of the neck and/or patchy plumage on the upperparts (Manx apparently has a more stable black pigment; Yésou et al. 1990). More confusingly, some Balearics are peculiarly dark, with a limited dusky patch confined to the breast or central belly (and thus invisible when sitting on the water). Such birds may be confused with Sooty Shearwater and size and structural differences then become important (see Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus). A minority of Balearics are more extensively white below, resembling Yelkouan Shearwater P. yelkouan, which replaces Balearic in the e. Mediterranean. Also bear in mind that some worn Manx can appear distinctly brown-toned above, particularly in bright sunlight.

Ageing Although variable in their plumage tones, from July to September, juveniles can be distinguished from adults by their darker, fresh and immaculate plumage at a time when adults are often worn and showing traces of moult. Pale juveniles are apparently scarce. Ageing becomes increasingly difficult as the adults approach the end of their moult, which is completed in October (Yésou et al. 1990).

On the face of it, easily identified: an all-dark shearwater which, in good light, shows a distinctive silvery centre to the underwing. The problem, however, is dark Balearic Shearwaters (see Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus). The easiest way to separate them is by shape: Sooty is a rather fat, bulky-bodied shearwater, with long, narrow, pointed wings that are usually angled back from the carpals and slightly bowed, creating a ‘mini-albatross’ shape (at distance, they may vaguely suggest dark-phase Arctic Skua Stercorarius parasiticus). Balearic is closer to Manx in shape, so it has proportionately broader, shorter wings that are held more stiffly, less angled back. When flying with a strong tail wind, Sooties tend to ‘bound’ over the sea in a series of high arcs, but the flight is more languid in calm conditions. Balearics typically fly closer to the surface with a more direct flight on stiffer wings and a flappier action. Although size comparisons are particularly difficult at sea, Sooty is about 15–20% larger than Balearic.

Reference Yésou et al. (1990).

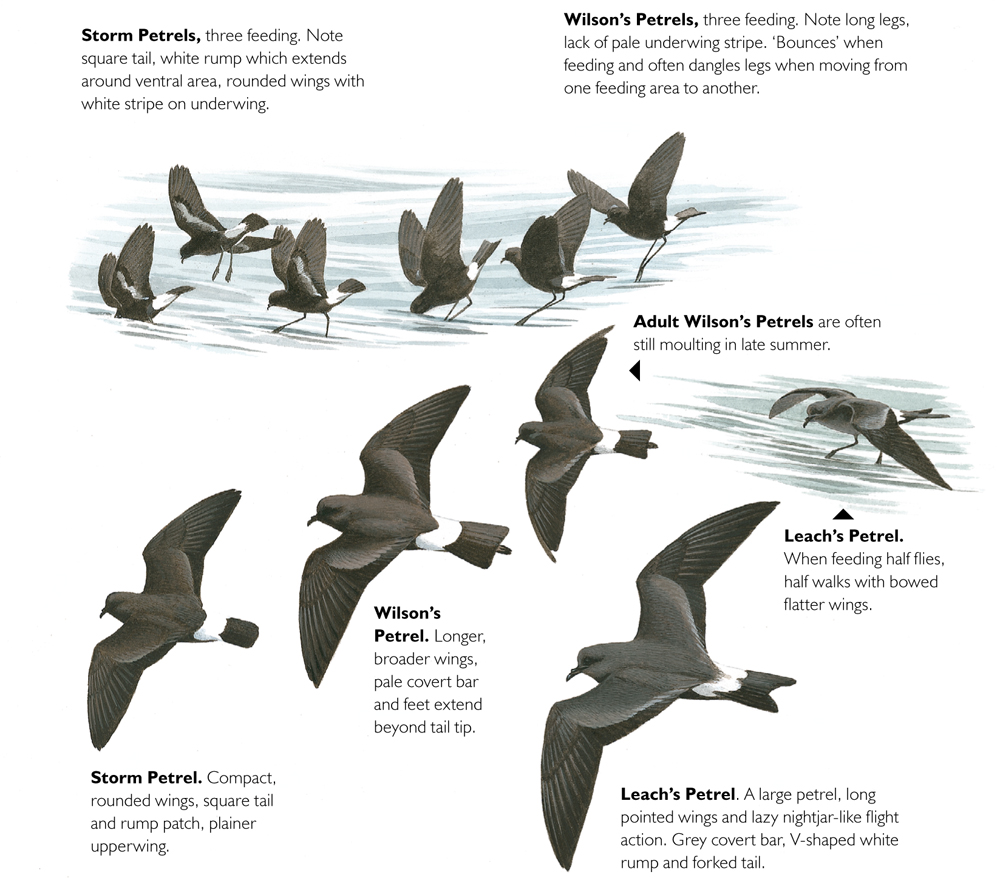

Where and when Storm Petrel is a numerous breeder on northern and western coasts, but is usually seen from shore only after gales. Leach’s Petrel breeds in small numbers off w. Scotland and Ireland, as well as in the Faeroe Islands and Iceland, but migrants thought to originate from the larger North American colonies occur in late autumn and winter. They can be found from early September to February, but the peak month is usually November. Large numbers are occasionally ‘wrecked’ and Merseyside has proved to be the area where they occur most regularly, sometimes in considerable numbers during north-westerly gales. Leach’s are more likely to be seen inland than Storm. Wilson’s Petrel was once regarded as a very rare vagrant from the Southern Hemisphere but is now known to be reasonably numerous in the western approaches in July–September (as many as 103 were recorded in 1988). However, to see this species it is essential to book onto an organised pelagic trip, the most reliable ones being from the Isles of Scilly or off w. Ireland.

General approach Given a good view, the three species are not difficult to identify but, since many sightings are brief, distant and during inclement weather, caution is recommended. Although seawatching experts can separate them by flight alone, less experienced birders should rely more on their shape and plumage; also bear in mind the difficulties of interpreting and accurately describing flight actions. Particular caution is demanded when identifying Wilson’s but on a pelagic trip they can often be attracted close to the vessel by the use of ‘chum’.

Size and shape A small petrel (about two-thirds the size of Leach’s) with a square tail and relatively short, quite pointed, rather triangular wings that lack a definite angle at the carpal joint. The wing-tips appear slightly more rounded when feeding. Unlike Wilson’s, the legs are short and are not normally visible except when foot paddling.

Plumage Appears black, with a prominent contrasting square white rump that extends onto the sides of the ventral area (unlike Leach’s). Unlike Leach’s and Wilson’s, it has plain upperwings, lacking a prominent pale grey panel across the coverts. At close range, however, adults show slightly browner greater coverts and juveniles a more clear-cut but narrow whitish greater covert bar. The most distinctive feature is a prominent white line on the underwing, lacking on both Leach’s and Wilson’s.

Flight Usually seen flying low over the water like a bat or a big black House Martin Delichon urbicum (unlike Leach’s, inland Storm Petrels can be quite difficult to pick out from hirundines). Normal flight is fast and fluttery, with quick, flappy wingbeats and short glides on quite bowed wings. It shears over the waves when travelling more purposefully. When feeding, it flies into the wind and then hangs in one place, either foot paddling or sitting on the water with the tail splayed and the wings raised 10–20 degrees above the horizontal.

Size and shape Noticeably larger than Storm Petrel; in size and shape resembles a small Black Tern Chlidonias niger. Colour and shape may also suggest a miniature Arctic Skua Stercorarius parasiticus (it is sometimes mobbed by Black-headed Larus ridibundus and Common Gulls L. canus). Long, rather pointed wings, noticeably angled back from the carpals, and a longish forked tail (adults moult in late autumn and winter and can at times look slightly rounder-winged, while the tail fork can be very difficult to see at any distance). When sitting on the water, it looks long and horizontal with a long rear end.

Plumage Slightly paler than Storm Petrel, appearing dark brown. The most distinctive feature is a broad, dirty grey band across the upperwing-coverts, also visible at rest; this can, however, largely disappear on moulting adults. The white rump is narrower than on Storm Petrel and is V-shaped when seen from above; a narrow dark central bar may be visible at close range, but is often difficult or impossible to see at a distance, when the rump itself is less obvious than on Storm.

Flight Buoyant, effortless, and also slower and lazier than Storm, with an easy action recalling Black Tern or European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus (it is possible to count each wingbeat). In travelling flight, it shears up from the surface to bound forward, often with sudden changes in speed and direction (again recalling European Nightjar) but its wing-beats are deeper and ‘flappier’ when flying into the wind. When feeding, it hangs over the surface with swept-back wings, slightly bowed and flatter than both Storm and Wilson’s; it then half-flies, half-walks across the surface.

Size and shape When seen well, not difficult to identify, but most observers unfamiliar with the species initially find it difficult to pick out from Storm Petrel, with which it associates. Distinctly larger than Storm and, although basically similar in shape, the longer and broader wings are more rounded and hence rather paddle-shaped. Also, the rear edge of the wing is very straight. However, in travelling flight the wings look more pointed, with the primaries more angled back. In late summer (when most occur) many are moulting and the old outer primaries often project beyond the still-growing new inner feathers, producing a hooked effect to the wing-tips (most Storm Petrels seen at this time are fresh juveniles). Of particular importance is leg length: the long legs are prominent when feeding and are often trailed at 45 degrees when flying short distances; in full flight, the legs project quite prominently beyond the tail (but the diagnostic yellow webs to the feet are incredibly difficult to see in the field).

Plumage Paler than Storm Petrel, looking more faded, but the best feature is a broad pale grey upperwing panel, obvious at closer ranges (similar to Leach’s and unlike the plain-winged Storm). The rump is more obvious than on Storm, extending further onto the sides and appearing to be continuously on view. It may show a diffuse pale stripe on the underwing, but it lacks the prominent white underwing line of Storm Petrel (being a ‘negative’ feature, the lack of this character is not always immediately apparent).

Flight Full flight is vigorous and direct, with rapid wingbeats followed by short glides, often several metres above the surface (recalling Swallow Hirundo rustica). When feeding, the wings are held in a shallow V while foot paddling with its long legs. The feeding flight is slower, easier and more butterfly-like than Storm Petrel, tending to glide, skim and skip over the surface of the waves with the legs dangling and the wings slightly bowed.

References Flood (2010), Harrison (1983).