Where and when Cormorant is common around all British and Irish coasts, as well as on inland waters, larger rivers and canals, even in cities. Note that the Continental race sinensis has colonised Britain and is spreading (see ‘Continental Cormorants’ Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis). The less widespread but more numerous Shag is essentially marine, commonest around rocky coastlines in the north and west, but rare inland (mostly in autumn and winter). Separating them is not always easy, particularly at a distance. Difficulties often arise with out-of-context Shags, particularly inland. A detailed description would then be essential for acceptance.

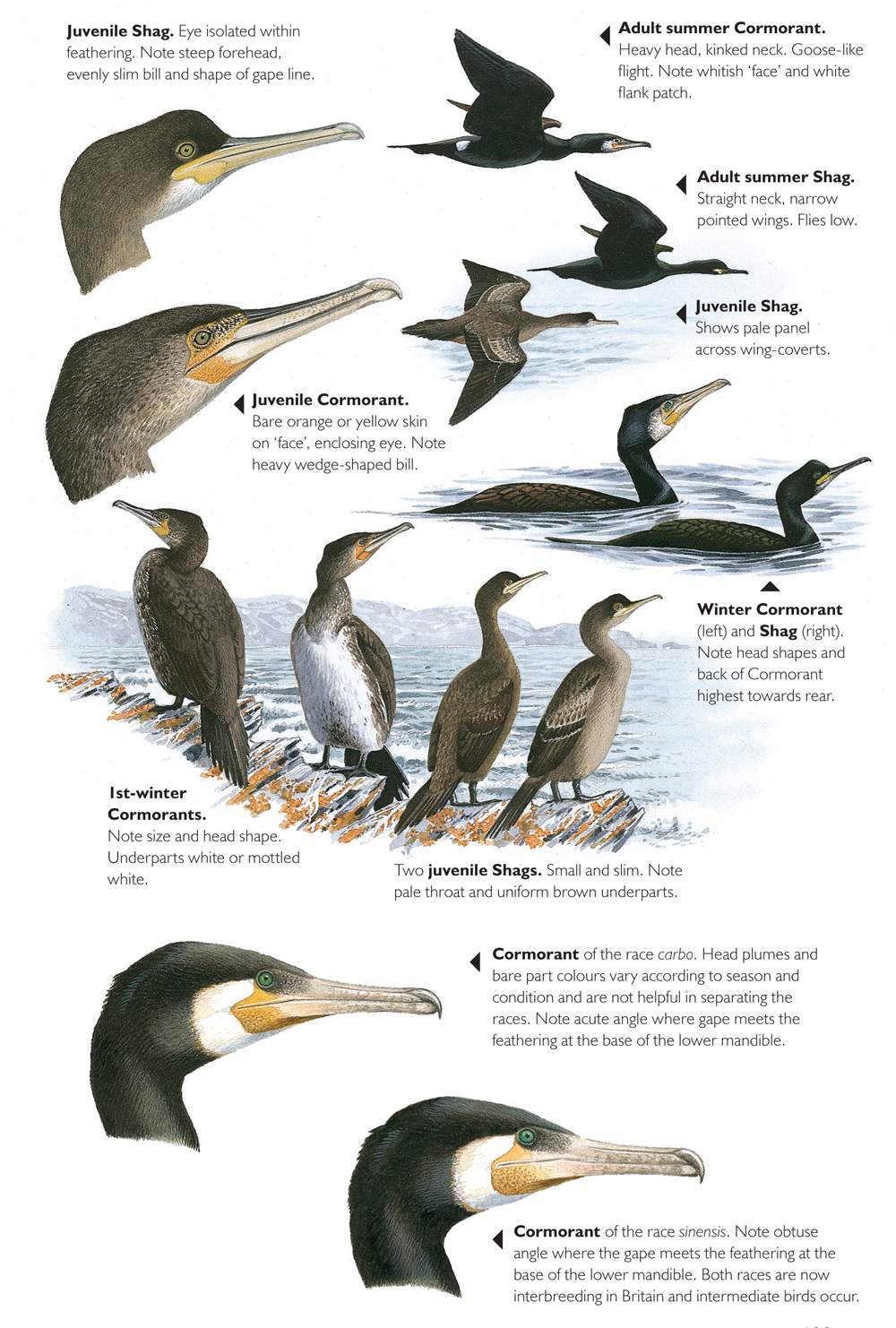

Size and structure Most birders separate Cormorant and Shag by a combination of size, structure and ‘jizz’. Cormorant is larger and towers above Shag at rest, although the height difference is emphasised by its tendency to hold its head and neck higher. However, Cormorants exhibit considerable size variation and particularly small females can look Shag-like if seen in isolation. Cormorant is bulkier, heavier and more angular than Shag, particularly when out of the water, with a thick neck and a heavy, angular head. A lower forehead and more tapered bill produce a more wedge-shaped head and bill profile. In flight, Cormorant looks heavy and massive, with a larger head, a thicker, slightly kinked neck and slow, rather goose-like wingbeats.

Facial pattern At close range, pay particular attention to the fact that Cormorant has an extensive area of bare skin on the lores, face, chin and throat, extending narrowly above and behind the eye; this is often referred to as the ‘gular patch’. On adults, this area is yellow in winter but, in breeding condition, the portion below the gape line becomes dark green, while the area immediately below the eye brightens from cream to bright yellow or orange and then to bright red during mating and egg laying. Note, however, that the bare skin on adult Cormorant’s lores and chin is often obscured by minute black feathering, so some are less distinctive than others. On immatures, the whole of this facial area is usually yellow or pale orange and, even at a distance, individuals with extensive patches can be safely identified as Cormorants (Shags never show orange on the face).

Plumage Adult and second-year Adults in breeding plumage are readily identifiable. As well as the yellow or orange face, Cormorant has large white facial and flank patches, a purple-blue sheen to the head and underparts, and a bronze gloss to the upperparts (with broad dark feather fringes). White filoplumes on the head may be extensive and conspicuous (see below). Both species start to acquire winter plumage soon after they finish breeding and both become duller. Cormorants then lose their white flank patches, have a much duller white facial patch and lack the white filoplumes on the head; the bare facial skin may turn cream. Breeding plumage may be acquired again as early as late December (see below for racial differences). Juvenile/first-winter Both species are very variable, compounded by the fact that they undergo an almost continuous body moult from their first autumn until they acquire adult plumage two years later. Cormorant is blacker than Shag and usually much whiter below, many showing strikingly white underparts. Some are brown below, while on others the white is confined mainly to the belly (often looking mottled and ‘moth-eaten’ when moulting). Conversely, a few are the opposite, being blackish on the belly and brown on the neck and breast. Juvenile/first-winter Shag is distinctly paler and browner than Cormorant, normally showing pale brown feathering on the underparts, and lacking the obvious whiteness of most young Cormorants (but note that juvenile/first-winter Shags with very white underparts are occasionally recorded; see Shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis). Older immatures Both species become darker with age, with second-years similar to winter adults, but duller and browner.

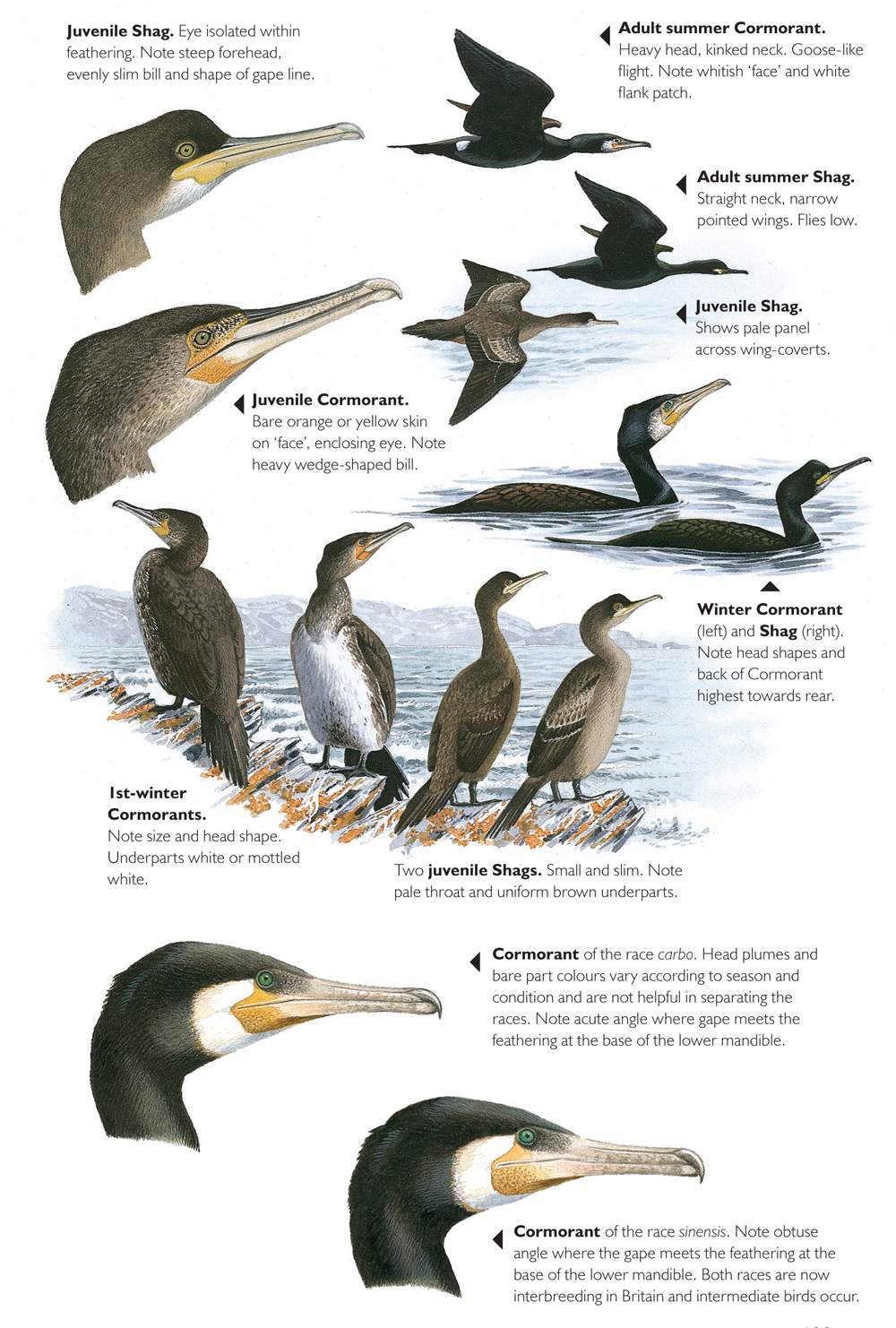

The race of Cormorant that has traditionally bred in Britain is nominate carbo, which usually nests on sea cliffs, mainly in northern and western areas. However, since the early 1980s, birds of the Continental race sinensis have colonised, nesting in trees and bushes on inland waterbodies. They have subsequently spread west and are now common in many areas. It has been established, however, that carbo and sinensis are now interbreeding in some areas (Ekins unpubl.). Shape of the gular patch The only way to separate the races with any degree of confidence is by the shape of the bare gular patch. In carbo, the bare skin extends downwards and backwards from the eye and forms a fairly acute angle at the base of the gape before sloping down and then forwards again towards the chin. On sinensis, the bare skin also extends downwards and backwards from the eye but, instead of forming an acute angle at the gape line, it drops vertically towards the throat (see illustration). In other words, carbo has an ‘acute’ angled patch, sinensis a ‘square’ one. Other differences Other ‘on average’ differences are much more difficult to evaluate and bear in mind that intergrades between the two forms will confuse the issue. Carbo averages 25% larger than sinensis, tending to make the latter look distinctly smaller and slighter in direct comparison, but this difference is obfuscated by the fact that male Cormorants of both races average 20–25% larger than females (males also have a longer bill with a more prominent hook at the tip). Adult sinensis can acquire breeding plumage by late December and most are in full breeding plumage by late January. Adult carbo typically acquires breeding plumage later, although some can be in full plumage by early February. Despite assertions to the contrary, in breeding plumage there is no difference between the two races in the extent of the white on the head. Juvenile sinensis tend to look smaller, shorter-billed, darker-bellied and longer-tailed than carbo. Classic birds show much less white on the belly, with just a few paler feathers confined to the central belly and upper breast, forming a paler ‘T’-shaped area on the breast.

Size and structure Distinctly smaller, slimmer and slighter than Cormorant with a smaller head (more rounded at the rear), a steep forehead (but flattened when diving) and a narrow, parallel-sided bill. In flight, it looks slimmer and scrawnier, with a smaller head and a thinner, straighter neck. It also has narrower wings and more tapered primaries, which produce a quicker flight action. Of interest, Cormorant has 14 tail feathers, Shag 12: a surprisingly useful difference when identifying corpses (unless in tail moult). In breeding plumage, adult Shag shows a very distinctive forward-pointing crest on the forehead, while even non-breeding adults and first-winters may show ragged feathering on the forecrown (conversely, Cormorants often show ragged feathering on the back of the head).

Facial pattern Adult summer Shag lacks Cormorant’s large bare ‘gular patch’ on the face and around the eye. Instead, adults in breeding condition have a relatively small area of bare skin confined to the chin, although this is often peppered with, and obscured by, minute black feathering. More distinctive is the swollen bright yellow gape line, which extends below and behind the eye. Unlike Cormorant, the rest of the face and throat is feathered, with the green eye isolated within the feathering. Juvenile and non-breeding adult The pattern is similar but the entire lower mandible is yellow or greenish-yellow, extending below and behind the eye to include the obvious gape line. Behind the bare chin, the feathered throat is noticeably white. The eye is completely enclosed by the facial feathering but, in juveniles, it is initially yellowish-white with a fine yellow orbital-ring.

Plumage Adult and second-year In favourable light, breeding adult Shag shows a subtle but obvious green sheen to the plumage (with narrow black feather fringes on the upperparts). Same-age Cormorants show a purple-blue gloss to the underparts and a bronze gloss to the upperparts, with broader and more obvious black feather fringing. Both species are duller in winter; Shags then gain a white throat but lose the forehead tuft (although some may regrow it by early December). Juvenile/first-winter Juvenile Shag is a much paler grey-brown than juvenile Cormorant, particularly on the underparts (it lacks Cormorant’s bronze tint to the upperparts). It usually shows noticeable whitish fringes to the median and greater coverts, whitening with bleaching and wear so that, by their first summer, these feathers produce a conspicuous pale upperwing panel, obvious in flight. Young Shags have pale legs and feet (flesh-brown, yellow-brown or yellow; black on Cormorant).

Behaviour Although not diagnostic, behavioural differences are useful. Shags tend to fly low over the waves and avoid crossing land, whereas Cormorants often fly at considerable height (inland birds may soar high in the sky). Shags often feed in large, dense flocks whereas Cormorants are rather more solitary when fishing, although they too (perhaps mainly sinensis) sometimes feed in large flocks, with the birds at the back repeatedly flying to leap-frog those at the front. Both species jump clear of the water when diving, but this is particularly marked in Shag, which often enters the water almost vertically. Shags are often very tame, so an unusually approachable ‘Cormorant’ is always worth a second look. Both species roost communally (including by day).

Juveniles of the Mediterranean race are very pale, usually with extensively whitish underparts (with contrastingly dark thighs) and a noticeable pale area on the wing-coverts (which appears as a prominent pale panel in flight). The legs are obviously pale pink. Such birds are not infrequent in extreme SW England but, rather than originating in the Mediterranean, it is perhaps more likely that they are simply pale individuals thrown up by our own population.

References Ekins (unpubl.), Garner (2008).