Where and when Formerly confined to central Wales, as a result of reintroductions the Red Kite has increased spectacularly in recent years and is now a familiar sight in many parts of the country, even over some urban areas. Winter and spring dispersal produces records elsewhere including, on occasion, small flocks. Formerly an extreme rarity, Black Kite is now an annual visitor, currently averaging about 14 records per year (with a peak of 32 in 1994). Early birds appear in March, records increasing to a peak from April to June, with a few seen until late autumn (the nominate race has wintered once).

Structure and flight A stunning raptor which, at distance, can look like a flying cross. It has long, rather narrow wings that are often angled back from the carpals. They are held flat or arched when soaring or gliding (inner wing slightly raised, outer wing slightly depressed, with the tips marginally upturned). Immediately separable from Common Buzzard Buteo buteo as the latter has shorter, more rounded wings and tail, and soars with its wings held in a V (although it frequently glides on flat wings). Red Kite’s wingbeats are deep and elastic, producing a buoyant flight. The distinctive tail is long, deeply forked and often twisted in flight. When soaring, the fully spread tail looks much squarer, although it usually retains a noticeable notch. Note that the tail fork can be lost through heavy abrasion and in the late summer moult it can become very irregular in shape.

Plumage Rich orangey-brown, with a noticeably paler head. The following features are particularly obvious. 1 UNDERWING A large, square white patch across the inner primaries and the bases of the outer primaries. 2 TAIL A beautiful pale cinnamon-orange. 3 WING-COVERT PANEL A striking pale panel across the median upperwing-coverts. Juvenile The general plumage tone is paler and buffier than the adult. Juveniles of both species can be aged by their immaculate plumage, which has better-defined pale fringing to the feathers of the back and upperwing-coverts. However, the most obvious difference from adults is that, on the upperwing in flight, juveniles in fresh plumage have very distinct whitish tips to the greater coverts (including the greater primary coverts) and also to the trailing edge of the wing. These form two narrow but noticeable parallel lines across the rear of the upperwing. Juveniles also show a buff tip to the tail. All these tips are gradually reduced by wear and juvenile plumage is gradually lost through a variable winter body moult, although some are still in complete juvenile plumage by the following spring.

Call A surprisingly thin, husky weee-oooo wee-oo wee-oo etc., very weak compared to Common Buzzard.

Structure and flight It is essential that Black Kites are identified with care and only those seen well should be claimed. Red Kite should be used as the yardstick. Black Kite shares Red Kite’s basic shape and jizz, being a long-winged, long-tailed raptor with a distinct tail fork. However, beware of Red Kites with a severely abraded or damaged tail, giving the impression of a shallow fork or even a square-ended tail (most likely in spring or summer). Like Red Kite, but unlike Common Buzzard and Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus, it flies and soars on flat wings that are often arched downwards from the carpal joint. It has deep and rather elastic wingbeats that produce a rather ‘flappy’ flight. Like Red Kite, the long tail is often used as a rudder, twisted and turned as the bird moves around. Black Kite is smaller and more compact than Red Kite, with shorter wings and a shorter tail (about 10% and 20% shorter, respectively). The tail lacks the deep and obvious fork of Red Kite, instead showing a shallower notch that is obvious only when the tail is closed (the tail fork may even be absent on heavily abraded birds). When soaring, the spread tail often loses the notch completely and instead shows a completely straight rear edge. This often causes confusion with other large raptors but it should be noted that, even when the tail is spread, it still shows sharply pointed corners, unlike the more rounded tail tips of Common Buzzard, Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus and Marsh Harrier.

Plumage As its name suggests, the other main difference is its colour: whereas Red Kite is a richly coloured reddish or orangey-looking bird, Black Kite is a much darker chocolate-brown (sometimes tinged rufous below). This difference is most apparent with reference to the tail. On Red Kite, the upperside of the tail is strikingly cinnamon-orange (greyish on the underside) but on Black Kite it is dark chocolate-brown, concolorous with the rest of the plumage (sometimes with a slight cinnamon tinge). This difference is echoed by the rest of the plumage, Black Kite being a much more subdued, less colourful bird than Red Kite, lacking the latter’s strong contrasts. Worn adults may be particularly dull. In particular, it has much less prominent pale patches on the bases of the under-primaries, where Red Kite shows conspicuous white ‘windows’. The head too is duller, as is the pale panel across the upperwing-coverts, which is usually very obvious on Red Kite. Juvenile Ageing differences as Red Kite (see above) but juvenile Black Kite is distinctive in that it has extensive pale buff spotting and feather fringing on the back and upperwing-coverts, and obvious buff streaking on the underparts; it also shows a blackish mask through the eye. The under-primaries are barred black and white. This plumage is retained until the following summer, but wear and a variable body moult produce a more uniform appearance by then.

Call A drawn-out, rather tremulous wee-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o.

Perhaps the commonest confusion arises with high-flying female, juvenile and immature Marsh Harriers . Like all harriers, when soaring or gliding Marsh holds its wings in a shallow V (which easily separates it from Black Kite) but, when directly overhead or in a steadily flapping flight, the wings can look flat (even at lower levels Marsh Harrier can, over short distances, look flat-winged). High-flying female and juvenile Marsh Harriers look uniformly dark, any yellow/golden on crown and throat being difficult to see. In addition, females and immatures can show a slightly paler patch at the base of the primaries while, from late spring onwards, first-summer males can show grey feathering which could perhaps be misinterpreted as the pale primary patch of a Black Kite.

Given its rather short-tailed/round-winged shape, Common Buzzard is a less likely confusion species, particularly since its V-shaped wings are usually so obvious. Another source of confusion is provided by Honey Buzzard, particularly darker individuals. Like Black Kite, Honey Buzzard has rather long, flexible wings that are held flat when soaring. Its tail is also longer than Common Buzzard’s, but note that both its wings and its tail tend to look somewhat paddle-shaped. Like Black Kite, dark Honey Buzzards show pale areas on the inner primaries; indeed, the most common plumage of juvenile Honey Buzzard is all dark with pale inner primary windows, so be particularly careful in autumn.

There have been rare cases of hybridisation between Red Kite and Black Kite, and controversial birds have been seen in Britain. As with any rarity, make sure that a potential Black Kite does not show intermediate or anomalous characters.

There is a single British record (Lincolnshire and Norfolk, winter 2006/07 but subject to formal acceptance) of the e. Palearctic race lineatus or ‘Black-eared Kite’. It differs from the nominate as follows: (1) wing-tip shows six deeply splayed primaries (rather than five) producing a squarer wing shape; (2) it has brighter and more distinct barring on the inner primaries; (3) the under-primary patches and the pale panel on the upperwing-coverts are whiter and more contrasting, almost suggesting Red Kite. Being a winter record, it occurred at a completely different time of year from our usual overshooting spring vagrants. Photographic evidence would be essential.

Reference Forsman (1999).

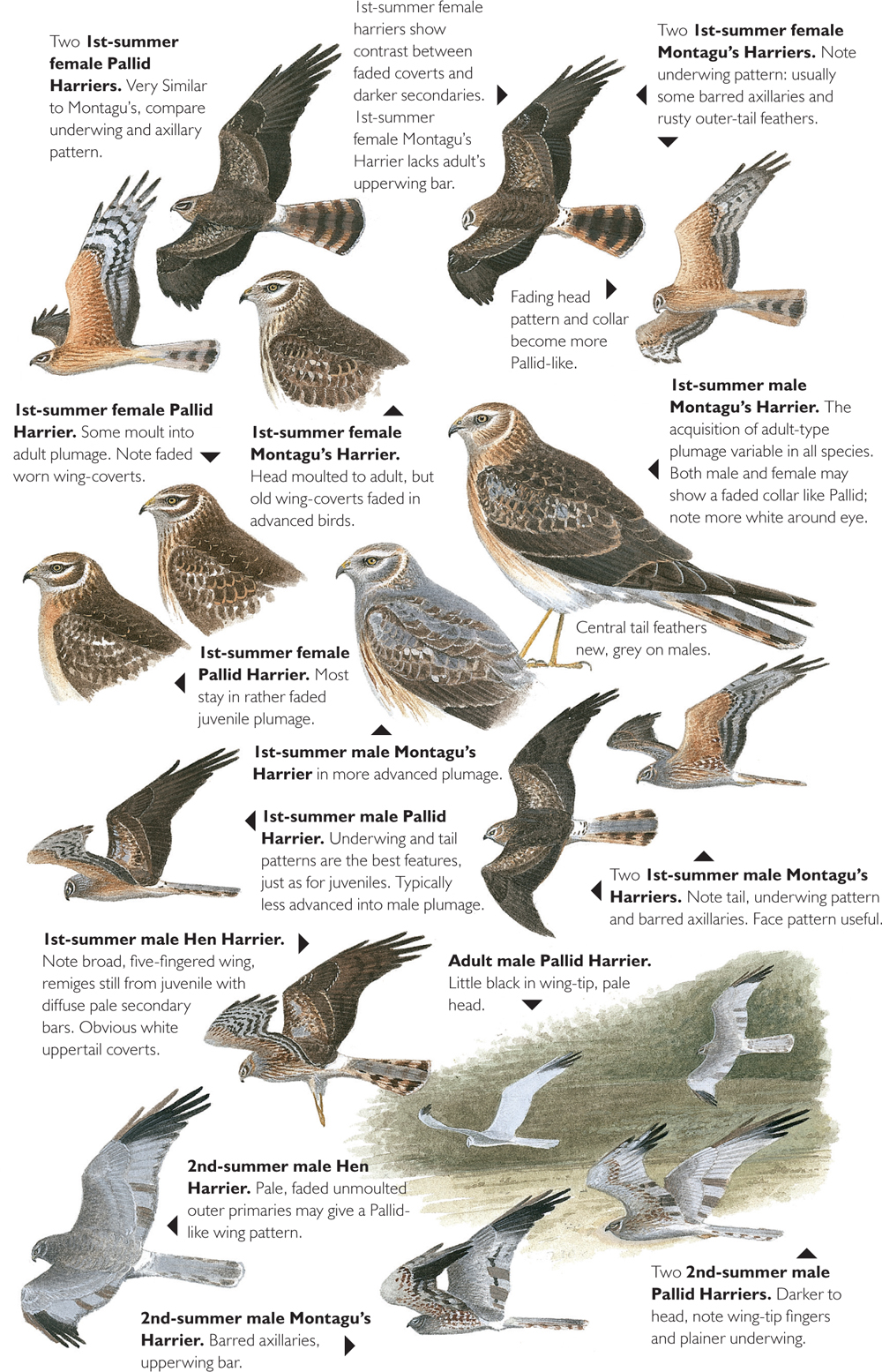

Where and when Hen Harrier breeds mainly on upland moorland and in young conifer plantations in Scotland (particularly Orkney), Ireland, Wales and n. England; gamekeepers have exterminated it from many areas and it is almost extinct in England. More widespread in winter, but still scarce, frequenting all kinds of open country, particularly moorland and coastal marshes. It is most numerous on e. English coasts, but numbers of Continental immigrants are variable. Montagu’s Harrier is a rare summer visitor, mainly from April to September, breeding mostly on heaths and arable land in s. and e. England (12–16 pairs in 2010). Pallid Harrier was formerly an extreme rarity, with just three records up to 1992. An influx of five in 1993 was then followed by a further 21 up to 2010. A remarkable influx then occurred in 2011, with 29 accepted, mostly juveniles in September–October. The upsurge is apparently related to a westward expansion of the species’ European breeding range. Unlike Montagu’s, records have also occurred in winter and early spring. There are three British and three Irish records (to 2012) of the North American Northern Harrier (late autumn and winter).

General features All have a long tail and relatively longish wings which they hold in a shallow V, most obviously when quartering low over the ground. Adult males are essentially grey and black, whereas females and juveniles are brown with prominent white uppertail-coverts (usually erroneously referred to as the ‘rump’). Juveniles can be sexed by their eye colour (pale in males, dark in females) but this can be very difficult to determine in the field. Males acquire little if any adult-like plumage until a complete moult when one year old. They are then similar to adult males, but are generally browner and retain obvious traces of immaturity.

Structure Hen is larger and bulkier than Montagu’s and about 30–40% heavier, with proportionately shorter, broader and more rounded wings which contribute to a heavier, less graceful flight. Particularly when high overhead, Hen may recall a giant Accipiter. At times, however, Hen Harrier’s wing-tips can appear quite pointed.

Plumage Adult male A stunning bird: the soft pale grey head and upper breast contrast with the whiter underparts to produce a slightly hooded effect. The grey also contrasts smartly with the extensively black outer primaries and, most distinctively, a thick but variable blackish trailing edge to the underwing. It also has white uppertail-coverts and a fairly plain tail. Adult female Brown above with prominent white uppertail-coverts and noticeably streaked below on a buff or whitish background (streaking strongest across the breast). The underwings are heavily barred across the primaries and secondaries. It has white surrounding the eye but the face is otherwise relatively plain and owl-like, with a narrow whitish border. Juvenile Compared to adult female, juvenile shows neat and immaculate plumage with a narrow whitish trailing edge to the wing and buff tips and fringes to the dark brown upperwing- coverts (the latter forming a paler panel). Buffier below than the female and variably streaked over the breast, belly and flanks; some are quite rusty below (Stoddart 2012). The under- secondaries are darker than adult female and more diffusely barred. Unlike Montagu’s and Pallid Harriers, deep orange individuals are rare (such birds are discussed under Northern Harrier).

Structure Montagu’s is slimmer and more graceful than Hen Harrier with a long, narrow tail and long, narrow wings with a distinctly tapered wing-tip (only three or four prominently fingered primaries, compared with five on Hen). Whereas Hen may suggest a giant Accipter, Montagu’s may suggest an oversized falcon. The long, supple wings of Montagu’s produce a slow, easy flight action which may recall that of Common Tern Sterna hirundo. Adult male Montagu’s can be separated by the following features. 1 GENERAL APPEARANCE It has a darker grey head, mantle and leading wing-coverts, all of which contrast with paler grey greater coverts and secondaries to produce a two-toned area of grey on the upperwing. Below, the darker head and upper breast contrast with the paler belly and underwings; the belly and flanks are lightly streaked with rufous. 2 UPPER SECONDARIES There is a black bar across the base of the upper secondaries. 3 UNDERWINGS Two black bars cross the bases of the under-secondaries (with a dark grey trailing edge) and variable brown flecking on the underwing-coverts. 4 TAIL Barred sides to the tail (best seen from below or when spread). Adult female Plumage very similar to Hen Harrier and best identified by shape (see above). At close range, the most useful difference is facial pattern: whereas Hen shows a relatively plain, owl-like face, Montagu’s has a more contrasting face with a broad whitish ring around the eye, contrasting with a thick, dark brown crescent-shaped cheek patch. On the upperwing, there is a distinct dark band across the secondaries, immediately behind the greater coverts. The underwing-coverts and axillaries are distinctly barred. Juvenile Immaculate in fresh plumage, with a narrow whitish trailing edge to the wing and obvious paler feather tips and fringes to the dark chocolate-brown upperparts. The most striking differences from juvenile Hen Harrier are as follows. 1 UNDERPARTS Juvenile Hen usually has a slight but distinct ginger tone to the underparts, with heavy streaking on the breast and flanks. Juvenile Montagu’s is very variable in plumage tone. Some are pale orangey-buff on the underparts but darker individuals have the breast, belly and leading underwing-coverts intensely coloured, varying from dark buff to deep rufous-orange, with little obvious streaking (but more than on Pallid). The under-secondaries are dark. 2 HEAD PATTERN Hen shows white above and below the eye but has a rather plain, owl-like face, which is surrounded by a narrow pale collar. Montagu’s shows a more heavily patterned face with a broad and obvious broken white or buff ring around the eye (forming a short supercilium and a thick sub-ocular crescent) and this contrasts markedly with a broad, dark chocolate crescent-shaped patch that curves under the eye and onto the ear-coverts. Below this is a variable narrow buff collar. Note that juvenile Montagu’s lacks Pallid’s thick brown ‘boa’ on the neck-sides (see below). First-year male A variable post-juvenile body moult in their first year produces a mixture of juvenile and adult feathering (thus Montagu’s tend to be more advanced than equivalent-aged Hen Harriers) Melanism Both sexes and also juveniles have a rare but very distinctive melanistic form, males being sooty-grey above and blackish below; some have a contrasting silvery area on the bases of the primaries.

Occurrence patterns Given the recent upsurge in records, Montagu’s can no longer be considered the ‘default’ small harrier and it therefore follows that any small, slim-winged harrier should be very carefully scrutinised and, if possible, photographed. Since Montagu’s Harriers occur mainly from May to September, any small harrier seen in early spring (March to April), late autumn (October to November) or winter is much more likely to be a Pallid.

Structure Very similar to Montagu’s but with same-sex birds in direct comparison, Pallid appears slightly smaller, with narrower, more pointed wings and shallower, less elastic wingbeats.

Plumage Adult male Entire plumage strikingly pale whitish-grey, the only black being a narrow but prominent black wedge on the four longest primaries. The tail is only slightly barred on the outer feathers (best seen when spread). Adult female Very difficult to separate from Montagu’s, but the following subtle differences are most significant, although photographic evidence would be beneficial to confirm them. 1 HEAD PATTERN Pallid may show a stronger narrow pale collar below the ear-coverts (in front of the darker neck-sides). 2 SECONDARIES Pallid has dark secondaries, both above and below, on the underwing contrasting with the paler under-primaries (forming a two-toned appearance: pale outer wing/dark inner wing). Also, the under-secondaries usually show one or two pale bands that taper and dissipate towards the body (secondaries usually pale and more obviously barred on Montagu’s, but can be dark). 3 UPPERWING Usually lacks Montagu’s dark bar across the base of the secondaries. 4 UNDER-PRIMARIES Weaker dark trailing edge (on Montagu’s, the entire rear of the wing shows a dark border). 5 OUTER UNDER- PRIMARIES The dark bars are more irregular and the pale bars wider (usually more evenly barred on Montagu’s). 6 BOOMERANG There is usually a pale crescent (or ‘boomerang’) on the base of the under-primaries, immediately behind the carpal. Juvenile Similar to juvenile Montagu’s (note that the under-secondaries also appear blackish at any distance, but barring is visible at close range). The following are the main features. 1 UNDERPARTS Vary from orangey-buff to a deep orange-brown with little or no streaking. 2 HEAD PATTERN The most obvious difference is that Pallid has a very contrasting and striking head pattern with a buff or whitish eye-ring and a prominent buff or whitish collar, sandwiched between the dark brown ear-covert crescent and a thick, dark brown half-collar or ‘boa’ on the neck-sides. Montagu’s has a much weaker pale collar and lacks the obvious dark ‘boa’. Other features are much more difficult to evaluate in the field (again, photographic evidence would be beneficial). 3 UNDER-PRIMARIES Like adult females, the under-primaries have a weaker, more blurred dark trailing edge than Montagu’s (the latter’s primary tips are more solidly dark). The under-primaries are also contrastingly pale but the barring is somewhat irregular compared to Montagu’s. 4 BOOMERANG The pale bases of the under-primaries often form a pale crescent or ‘boomerang’ around the dark carpal. First- and second-year males Plumage sequences are similar to Montagu’s (see Montagu’s Harrier Circus pygargus) but, on average, immature Pallid is less advanced than similarly aged Montagu’s (Forsman 1999).

Hybrids As Pallid Harrier apparently spreads westwards, hybridisation with Hen Harrier has been recorded. An extremely thorny subject, but something to bear in mind if faced with a particularly difficult individual.

All but one of the British and Irish records have related to juveniles.

Plumage Adult male Distinctive, differing from nominate Hen Harrier as follows. 1 UNDERWINGS White, contrasting strongly with a more obvious broad jet-black trailing edge (strongest on secondaries). 2 OUTER-PRIMARIES Five black outer primaries (Hen shows six). 3 UPPERPARTS Darker grey, with more brown feathering admixed. 4 HOOD AND BELLY Grey hood contrasting with a white belly spotted orangey-brown. Juvenile Plumage may suggest a juvenile Pallid or Montagu’s but it has the structure of a Hen Harrier. The main differences from Hen are as follows. 1 BOA/HOOD ‘Classic’ juveniles have a uniform or heavily streaked dark brown neck-band (or ‘boa’) which almost joins across the foreneck. When viewed side-on, this gives the impression of a dark hood. 2 UNDERPARTS The hood contrasts strongly with very obviously orange-toned underparts and leading underwing-coverts, which appear either uniform or only lightly streaked. 3 UNDER-SECONDARIES Tends to show a darker patch at the base of the under-secondaries, although some Hen Harriers also show this. 4 UPPERPARTS Distinctly darker brown above with a large and contrasting white uppertail-covert patch. It may show warm rusty tones on the wing-coverts and tail. Identification is, however, complicated by the occasional occurrence of juvenile nominate Hen Harriers with rufous underparts. Consequently, observers of a potential Northern Harrier should try to obtain good-quality photographs and seek expert advice. For more detailed discussions, see Grant (1983) and Martin (2008).

References Grant (1983), Forsman (1999), Holling et al. (2012), Martin (2008), Stoddart (2012).

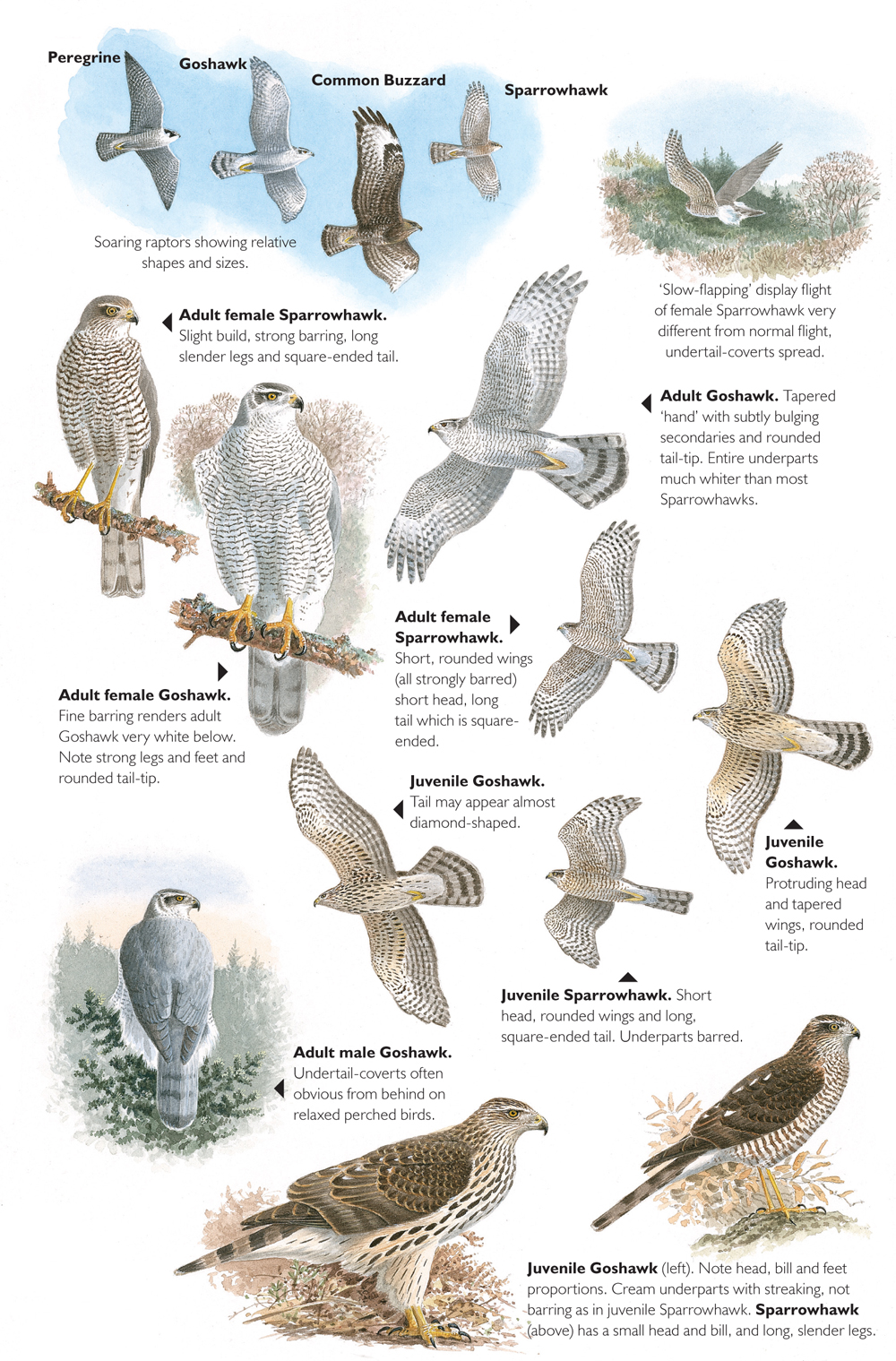

Where and when Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus is common throughout Britain and Ireland, but is less abundant in e. England. Extinct in Britain until the 1950s, Goshawk A. gentilis has become re-established, mainly through falconers’ escapes and re-introductions, and currently has a population of c. 450 pairs. It occurs in extensive tracts of coniferous woodland, particularly in Scotland, n. England, on the English/Welsh border and in the New Forest, and is now common in a few areas.

General approach Goshawk is a notorious ‘beginner’s bird’ and many birders pass through a phase of misidentifying Sparrowhawks as Goshawks. Its identification requires extreme caution and it is strongly recommended that observers gain experience of the species by visiting one of the well-publicised Goshawk viewpoints established in several areas (details online).

Size Larger than Sparrowhawk (female Goshawk averages about eight times heavier than male Sparrowhawk) but it can be extremely difficult to accurately judge the size of a lone bird, particularly against the sky or low over distant woodland. Despite statements to the contrary, Goshawks do not look ‘buzzard sized’, but intermediate between Common Buzzard Buteo buteo and Sparrowhawk. In direct comparison they are about three-quarters the size of a Buzzard and maybe twice the size of a Sparrowhawk, depending on the bird’s sex. Female Goshawks are c. 10% larger than males, but this difference is not usually obvious unless seen together. Goshawks tend to look ‘big’ rather than ‘huge’ but distant or lone birds high in the sky may not look particularly large at all.

Flight One of the reasons why they look big is because of their flight. Whereas Sparrowhawk has an energetic ‘flap-flap-glide’ flight with quick, shallow wingbeats, Goshawk has slow, deliberate, deep and rather elastic wingbeats. This creates a ‘flappy’ action that is somewhat crow-like (a useful analogy to remember). As well as soaring, they may hang in the wind, barely flapping, sometimes for long periods.

Display Goshawks and Sparrowhawks have similar displays. Goshawk has a protracted display period from late November onwards, reaching a peak in February/March, whereas Sparrowhawk’s display is confined to a more discrete period in early spring (late February to April). In addition, Goshawks display much more frequently, more habitually and more persistently. This normally consists of slow, lazy but exaggerated flapping in which the wings are raised and lowered well above and below the horizontal, recalling a displaying harrier Circus or a European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus (they may also slow their wingbeats in normal flight). Much more spectacular is the ‘sky dance’, which consists of a series of ‘switch-backs’ that involve a fast, deep plunge (with slow-motion flapping) before shooting vertically upwards like a bullet, with the wings held tight against the body. Although both species do this, its larger size renders Goshawk’s display by far the more impressive.

Shape Goshawk has a distinctive shape of its own: it is not simply a ‘big Sparrowhawk’. 1 WINGS Whereas Sparrowhawk has short, evenly rounded wings, Goshawk’s look distinctly paddle-shaped, particularly from a distance or when soaring. This is because the wings are proportionately longer and more tapered, and the trailing edge shows slightly bulging secondaries (not always noticeable). However, wing shape varies depending on what the bird is doing. In a descending glide or the initial stages of a stoop, the primaries may be swept back and pointed, prompting confusion with Peregrine Falco peregrinus. 2 TAIL Another useful feature is that the tip of the tail is rounded (noticeably square-ended on Sparrowhawk). However, the obviousness of this varies. When closed, the tail can look quite broad and tapered, with obviously rounded corners if looked for. However, when soaring it can appear strikingly paddle-shaped or, when more fully spread, diamond-shaped. Because of their long, rather tapered wings and rounded tail tip, their shape can be oddly reminiscent of Raven Corvus corax. 3 HEAD Also significant is a noticeably protruding head (apparent at most angles) creating a pointed head profile. This, combined with the longer, more tapered wings and longer tail, gives Goshawk an overall ‘rakish’ appearance. A very useful analogy is that Goshawk resembles a ‘flying crucifix’ whereas, because of its smaller, less protruding head and more compact shape, Sparrowhawk resembles a ‘flying T’ (i.e. ✝ compared with T). 4 UNDERTAIL-COVERTS In display the undertail-coverts are often fluffed out sideways (see below) often giving a distinct ‘stepped effect’ to the base of the tail. The spread undertail-coverts can make the tail look quite short, but note that this may also apply to Sparrowhawk.

Plumage Adult 1 UNDERPARTS An important feature is the colour of the underparts. Because the barring is fine and the background colour white, adults usually look uniformly whitish below, obvious even at long range (when the underwings may ‘flash’ white in flapping flight). In good light, their underparts and underwings may look strikingly white, especially when viewed against the trees. Although variable, Sparrowhawks look duller below as a consequence of having broader barring and slightly buffier background tones (orange barring and shading on adult males). 2 HEAD In close views, Goshawks often look obviously capped or hooded owing to their dark head and ear-coverts, which sharply contrast with the whitish underparts. This is usually most obvious on adult males, but some females have a very similar pattern (immature males and many adult females show a more diffuse head pattern). A white supercilium may be noticeable at close range, but not at a distance. 3 UNDERTAIL- COVERTS Despite statements to the contrary, in normal flight the white undertail-coverts are not obvious as they are sleeked down and do not contrast with the rest of the white or whitish underparts. However, when displaying, they are fluffed out to the side and even wrap around the sides of the rump; this means that they are most obvious not from below but from above or from the side, when they contrast with the blue-grey or grey-brown upperparts. They can even give the impression of a white rump or white sides to the rump (recalling a flying auk). The undertail-coverts may be much more obvious when the bird is perched, especially from behind when they may stick out either side of the tail base. Juvenile In a reasonable view, easily separated from adult by yellowish-buff underparts, with messy vertical streaking (not barring, as on adults and all ages of Sparrowhawk). However, the streaking is surprisingly hard to see at any distance so juveniles may simply appear rather uniformly buff below. They also have pale fringing to the upperpart feathers, rendering them browner above than adults. Juvenile plumage is retained through the first year of life and they may look rather worn by spring.

At rest Unlike Sparrowhawks, Goshawks often perch conspicuously in the tops of pine trees, their white underparts making them visible over considerable distances. Sparrowhawks are much more furtive and invariably perch within the canopy.

Calls Both species are largely silent but in the breeding season males utter an accelerating slow, rhythmic ki-ki-ki-ki-ki-ki-ki-ki; juveniles give a persistent begging peee-u peee-u peee-u that sounds plaintive and mournful . Inevitably, the calls of Goshawk are louder and stronger than Sparrowhawk’s, sometimes much harsher or with a ringing quality.

Other pitfalls High-flying female or immature Hen Harrier Circus cyaneus can appear quite Accipiter-like. Note the harrier’s slimmer proportions, rounded, well-fingered wing-tips, square tail and heavily barred primaries and secondaries (see Hen Harrier Circus cyaneus). Prolonged views should reveal Hen Harrier’s V-shaped wings (flat on Goshawk) and white uppertail-coverts. Goshawk is not confusable with Common Buzzard but is slightly more similar to Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus (see Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus): note differences in shape, plumage and flight.

Where and when Common Buzzard is now by far the commonest bird of prey in n. and w. Britain, and is continuing to increase and spread in eastern areas. Rough-legged Buzzard is a rare winter visitor, mainly to coastal e. England (sometimes e. Scotland). It currently averages c. 50 records a year but there are periodic influxes related mainly to the lemming cycle (exceptionally 319 in 1994/95). October records from western areas (e.g. Scilly in 1984 and 2001) are thought likely to relate to the North American race sanctijohannis (Flood et al. 2007). Honey Buzzard is a very rare summer visitor to selected woodlands in s. England, Wales and Scotland. It is also a rare late spring and autumn migrant averaging c. 160 records a year, but a huge influx in September–October 2000 brought over 2,200 into the country.

Structure and flight A rather stocky, evenly proportioned, broad-winged raptor, typically seen soaring over hillsides and woodland, often calling. Soars with wings held in a shallow V, but may glide on flat wings.

Plumage Adult Extremely variable but most are dark brown, often showing white on the throat and belly and/or a broad but diffuse whitish crescent across the lower breast, most obvious at rest. The bases of the under-primaries and secondaries are paler and greyer (barred darker) and there is a dark trailing edge to the underwing (better defined on male). The paler under-primaries can almost ‘flash’ as the bird flaps. Some are very pale, with a mainly white head, underparts and underwings (with dark crescent-shaped carpal patches) and a pale rump and tail. Such birds can easily provoke confusion with Rough-legged Buzzard (see below) or even Osprey Pandion haliaetus (note Osprey’s thick black eye-stripe and long, narrow, almost gull-like wings, which are distinctly down-kinked, never raised in gliding flight). Juvenile Similar to adult but in late summer they look immaculate at a time when adults are rather scruffy through moult and wear. They can also show paler upperwing-coverts, a rather diffuse trailing edge to the underwing and a narrower tail-band; the eye is pale (dark on adult). Juvenile plumage (and pale eye) is retained throughout winter but gradually wears.

Calls Adults have a well-known mournful mewing call. Begging juveniles are extremely vocal, giving a loud, mournful and rather irritating plee-u plee-u, commonly heard in late summer and early autumn (may persist into New Year).

The English east coast in October/November is the most likely place to see this species and winterers may linger into April or May. Elsewhere or at other times of year, identification requires extreme caution; note that, in western areas, pale Common Buzzards are far more likely. Genuine Rough-legged Buzzards are very striking – if not, think again.

Structure and flight A typical view is of a large, pale buzzard persistently hovering over coastal fields and marshes (with ponderous wingbeats) or hanging motionless, the tail twisted and turned like a kite’s. Common Buzzard also hovers, but less persistently. It is similar in shape to Common Buzzard but slightly larger, longer-winged and sturdier (but the head may look rather rounded at rest). It soars and glides with the inner wing slightly raised and there is a noticeable kink between the inner and the flat outer wing.

Plumage Juvenile Most of our Rough-legged Buzzards are juveniles. In flight they are striking, standing out through a combination of the following contrasting characters. 1 TAIL From above, a gleaming white base to the tail and white uppertail-coverts contrast with a thick black terminal band (narrower, diffuse and less distinct from below). 2 HEAD AND BREAST Predominantly creamy-white (may look very white-headed) contrasting with an obvious brownish-black belly. 3 CARPAL PATCH A large black carpal patch on the underwing. 4 UNDER-PRIMARIES Thick black tips to the outer under-primaries, but the tips to the inner primaries and secondaries are narrow and dusky. 5 UPPER-PRIMARIES A variable pale or white patch at the base of the upper-primaries. Ageing The best ageing character is the tail-band: on juveniles it is wider, duller and less clear-cut, whereas on adults it is narrow, black and sharply defined (both above and below) often with two or three narrower black bands towards the base (especially on males). Adults have dark eyes, juveniles pale. Adult male Compared with juveniles, adult males average darker (but lack the warmer tones of Common Buzzard). They have a dark head and breast (forming a hood) whilst the black belly patch is finely barred. They also have more heavily patterned underwing-coverts and perhaps more heavily barred under-secondaries and inner primaries. Adult female More like juvenile, having a paler hood than the male, less patterned underwings and a more solidly dark belly; unlike juveniles, they show a distinct black trailing edge to the underwing. The upperwings of adults are darker than juvenile’s with a less conspicuous pale patch at the base of the primaries. Note in particular that adult Rough-legged (especially females) often has a whitish U-shaped area on the lower breast, between the dark upper breast and the black belly (although many Common Buzzards also show this).

Pale Common Buzzards Some pale Common Buzzards can look similar to Rough-legged (see above) so the objective evaluation of size, structure, behaviour, date and locality are essential. Remember that pale Common Buzzards rarely show (a) a clear-cut black-and-white tail (any white is usually restricted to the uppertail-coverts) or (b) a pale patch at the base of the upper-primaries. Their carpal patches tend to be crescent-shaped (round or oblong on Rough-legged). Also, unlike Rough-legged, pale Commons often show creamy-white upperwing-coverts and usually lack a black lower-belly patch.

Structure and flight Similar in size to Common Buzzard but noticeably slimmer and less heavy. It floats around like a sailplane, often twisting the tail like a kite. Clearly establish the following features. 1 WING POSTURE Honey soars (and glides) on flat wings, with the tips often slightly drooped (never in Common Buzzard’s shallow V, but note that Common Buzzard sometimes glides on flat wings). 2 HEAD SHAPE A small pointed head protrudes prominently (strongly recalling Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus); note also that the head is narrow, not broad. 3 WING SHAPE In flapping flight the wings are proportionately longer and narrower than Common Buzzard’s, the primaries often looking straighter and narrower. However, when soaring, the wings appear distinctly broad and rounded (or ‘paddle-shaped’) with very rounded tips and rather bulging secondaries that have a ‘pinched-in’ effect where they meet the body. 4 WINGBEATS Slow, deep and rather elastic, with the wings noticeably bowed on the down-stroke, recalling a kite. 5 TAIL The tail looks proportionately long and narrow, and rather paddle-shaped when closed; when soaring it appears very full with a rounded tip. 6 The overall effect sometimes recalls a huge Accipiter, particularly when viewed side-on. Note that the juvenile is slightly shorter-winged and shorter-tailed than the adult.

Plumage Underparts extremely variable and complicated, from dark and rather uniform through medium and rufous to very striking individuals with a white head, underparts and underwing-coverts; see Forsman (1999) for more detail. Note that all show a large oval or rectangular black carpal patch on the underwing (as opposed to the more crescent-shaped patch on pale Common Buzzards). Adult On darker birds, there is a marked contrast between the dark body/underwing-coverts and paler primaries and secondaries. The following should be carefully noted. 1 UNDERPARTS BARRING Most show obvious barring on the breast, belly and underwings. 2 WING-TIPS Black extends around the tips and then along the tips of the secondaries to form a black trailing edge to the underwing. 3 PRIMARY AND SECONDARY BARRING Black bars across the bases. 4 TAIL A black band across the tip with one or two narrow, less obvious bands towards the base. Sexing 1 MALES Distinctly grey on the head and upperparts, and barred on the upperwing. The black trailing edge to the underwing is broad and well defined, but the under-primaries and secondaries are barred only across the bases, so the distal part of the feathers (behind the dark wing-tips and trailing edge) is unbarred. The tail usually shows only one narrow bar across the base. They also tend to be barred on the whitish belly. 2 FEMALES Browner above, lacking prominent barring. The under-primaries and secondaries are more evenly barred, with a narrower and less obvious trailing edge. Unlike males, they may show translucent inner primaries when backlit. The tail usually shows two narrow bars across the base (not one). They tend to be blotchy on the underparts, hence more uniform at a distance. Juvenile 1 GENERAL APPEARANCE Most are a uniform warm dark brown with noticeably paler under-primaries. As a consequence of their dark plumage, many juveniles are surprisingly similar to Common Buzzard, but are much plainer (the yellow cere being prominent as a result). However, like adults, the head and body plumage varies considerably and intermediate and very white individuals also occur. 2 PRIMARY AND SECONDARY BARRING Three or four rather faint bars across the primaries and heavier bars across the secondaries. 3 TRAILING EDGE Also a diffuse dark trailing edge to the underwing (note that juvenile’s under-secondaries appear dark in all morphs). 4 TAIL A less clear-cut terminal band to the tail and the dark bars across the base are also less noticeable. The upper tail is plainer than the adults’ and the feather tips are more tapered. 5 UPPERTAIL-COVERTS Many show contrasting whitish uppertail- coverts. 6 UPPERWING PANEL Many show a pale brown panel on the upperwing-coverts. 7 BARE PARTS At close range, they have a dark eye and a yellow cere (yellow eye and blue-grey cere on adult). Dark juveniles could also be confused with a high-flying juvenile Marsh Harrier, but that species glides on raised wings. The harrier’s tail is longer and slimmer in travelling flight and it usually lacks a pale under-primary patch.

Display Adults have a unique display that facilitates even long-range recognition: they raise their wings vertically over their back and then quiver them in a most peculiar manner. This occurs after an upwards swoop or in a series of descending swoops.

Calls Adults and begging juveniles have a disyllabic or slightly trisyllabic call, rather penetrating and more mournful than Common Buzzard.

References Flood et al. (2007), Forsman (1999).

Where and when Golden Eagle breeds only in mountainous areas of n. and w. Scotland (including the Hebrides), with a population of nearly 450 pairs. It has bred in the English Lake District, but not in recent years. It is rarely seen away from the Scottish breeding range, but dispersing immatures occasionally reach as far south as n. England. Having become extinct in Britain in about 1916, White-tailed Eagle has been re-established in w. Scotland with an increasing population (57 breeding pairs in 2011) mainly in the Hebrides (a re- introduction project is also underway in Ireland). Dispersing Continental migrants sometimes occur in winter in e. England, but their appearances remain erratic. Such birds frequent coastal marshes and farmland.

Moults Although it moults annually, Golden Eagle does not moult all of the body plumage or the flight feathers in any given moult, so they usually show different ages of feathers. White-tailed has a complete annual moult, but does not moult all of the flight feathers (Forsman 1999, which see for further details of moult and ageing).

Size and structure A huge raptor, with a wingspan c. 70% greater than Common Buzzard Buteo buteo. Despite this enormous difference, bear in mind that it can be surprisingly difficult to judge the size of high-flying raptors. With Golden Eagles, this problem may be exacerbated by the huge scale of the landscapes that they inhabit. Consequently, structure is especially important in their identification, particularly in their separation from White-tailed Eagle. Golden has very long, broad, well-fingered wings. They are narrower at the base, being ‘pinched in’ where the rear edge of the wing meets the body, producing a curved trailing edge to the inner wing (most obvious on juveniles). The tail is long (similar in length to wing width) and broad and square in shape. The head and neck protrude noticeably (an obvious difference from Common Buzzard). The wings are held either flat or in a distinct but shallow ‘V’, the latter a distinctive difference from White-tailed Eagle. The wings may, however, be arched, with a drooping ‘hand’ (Forsman 1999). In flapping flight, it has deep, slow wingbeats, followed by a prolonged glide (with primaries swept slightly back, the profile of the leading edge appearing rather S-shaped). When soaring, the wings are pushed slightly forward.

Plumage Adult Uniformly dark brown but, in a reasonable view, the crown and nape appear paler, the golden colour often clearly visible at closer range. Other plumage features are subtle: on the underwing, the basal primaries and secondaries are grey (lightly barred darker), forming a contrast with the brown underwing-coverts. The tail may also appear distinctly two-toned, the base being similarly grey with a broad dark tip (but some adults have an all-dark tail). When visible, the upperwing shows an irregular and variable pale panel across the coverts. Yellow legs may also be noticeable in a good view, particularly in favourable light. Unlike adult White-tailed, the bill is dark at all ages (with a yellow cere and gape-line). Juvenile The most distinctive plumage. Initially, juveniles are immaculate, very dark and uniformly brown, with a pale blond crown and nape (whitish to yellowish-golden). Most distinctive is the strikingly white tail with a broad and prominent black terminal band. In flight, they also have a large white patch at the base of the under-primaries (extending onto a few outer secondaries). They may also show a smaller white patch on the bases of the upper-primaries, but juveniles lack the adult’s pale panel on the upperwing-coverts. Second-year Similar to juvenile but plumage more worn and so distinctly paler; also shows a faded panel on the upperwing-coverts. Older immatures Golden Eagles take about five years to reach maturity, the areas of white in the wings and tail gradually diminishing over that period (rate varies individually). However, white in the base of the tail may be retained for five or six years, distinguishing subadults from full adults.

Size and structure Appears huge, particularly if seen in the context of the English countryside (in flight, aptly likened to a ‘barn door’). Long, broad wings, with slightly narrower ‘hands’, rounded wing-tips and fingered primaries. In flight, easily separated from Golden Eagle by a combination of (1) its front-heavy appearance, produced by a long, thick neck and a noticeably heavy bill, and (2) its short, slightly wedge-shaped tail (because of their white tail, adults can appear almost tail-less when viewed against the sky). It flies on flat or slightly bowed wings, with the primaries gently curved up at the ends (when soaring it can raise the wings into a very slight V). Juveniles show a distinctly uneven, ‘serrated’ trailing edge to the wing (straighter in adults). In flapping flight, it has deep wingbeats and a lazy, lolloping flight action, vaguely recalling Grey Heron Ardea cinerea. With its large bill, short tail and bulky body, it appears almost vulture-like on the ground.

Plumage Adult Brown, but distinctly paler yellowish-brown or whitish-brown on the head, neck and upperwing-coverts (a mixture of pale and dark brown often gives a rather ‘moth-eaten’ appearance). Older birds may look very pale-headed. A large, deep and strongly decurved yellow bill should be obvious; legs also yellow (unfeathered, unlike Golden Eagle). Tail white, very striking and obvious against a dark background but can often ‘disappear’ when viewed against the sky. Juvenile Very dark brown with feathers that are regularly patterned and of uniform age. The head is dark brown, but the neck and underparts are thickly streaked creamy-buff or golden-buff; more heavily patterned on the mantle, scapulars and wings (buff feathers with a brown teardrop or arrowhead pattern). The underwings are darker with a distinctive large, contrasting, messy pale patch on the axillaries and inner wing-coverts (retained almost into adulthood; Forsman 1999); also variable lines of white streaks on the underwing-coverts. The tail feathers have dark tips and outer webs but pale inner webs; the tail therefore appears darker when closed, but predominantly pale buffy-white when spread (although some show less white). Bill dark (with pale lores often obvious) and legs yellow. Like Golden Eagle, it takes about five or six years to reach adulthood. Second-year Exact pattern variable but often uniquely pale, with a dark head and a patchy mixture of a whitish-streaked upper breast and a large pale area on the lower breast, which in turn contrasts with the dark thighs. The back, scapulars and upperwing-coverts are often heavily patterned with whitish; in flight, the latter sometimes appear quite plain and sandy at a distance, contrasting strongly with the dark brown primaries and secondaries. The bill may begin to turn pale yellow. Older immatures Third-year plumage is usually somewhat intermediate between immature and adult-type. Thereafter, the plumage gradually becomes more adult-like. For more details, see Forsman (1999).

Behaviour Often feeds over water, plucking fish and birds from the surface (sometimes being attracted to offal from fishing and ‘eagle-watching’ boats). Also feeds on carrion.

Reference Forsman (1999).

General identification problems Given a good view, the separation of Peregrine, Merlin and Hobby is not difficult but, when seen poorly, all three can be confused. Remember that falcons seen very briefly are a real problem, as are birds high in the sky, when size cannot be accurately judged. Be prepared to leave such birds unidentified.

Where and when Peregrine breeds mainly on cliffs, in both coastal and inland locations, as well as on buildings in towns and cities. It has increased spectacularly in recent years, although it remains commonest in the north and west. Outside the breeding season, many disperse to coastal areas, particularly estuaries, or to inland sites where there is an abundance of suitable prey.

Flight, structure and behaviour A large, spectacular falcon. Shape distinctive: heavy, thickset and deep-chested, with broad-based pointed wings (although the extreme tips can appear rather blunt, particularly when soaring); it has a medium-length tail. Viewed from the side, the body looks rather cigar-shaped. It is likely to be seen high in the air, hanging in the wind or circling upwards before stooping at great speed at waders, pigeons, thrushes or other suitable prey. Compared to Merlin and Hobby, it is rather stiff-winged with shallow wingbeats in which only the tips are obviously moved (flight can recall Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis). When soaring and gliding, the wings are often held slightly bowed below the horizontal.

Plumage Adult Blue-grey above, with a variably barred, darker tail. It has a prominently white breast but the rest of the underparts look pale whitish-grey at a distance, an effect produced by delicate black barring on a white background. Thick black moustachial stripes stand out strongly against the white face and throat. Juvenile Browner above and darker below, the underparts heavily streaked brown; dark moustaches stand out strongly against a creamy face. It has a slightly paler forehead and sometimes a pale supercilium, which curves back towards the nape. Cere blue (yellow on adults).

Calls May be quite vocal in breeding areas, adults having a variety of calls including a persistent anxious slow, gruff kyaa kyaa kyaa kyaa kyaa ... or a loud and emphatic kee kee kee kee kee…. Also a weak chjik. In winter, a gruff, slightly muffled barking achik achik or archk archk may be heard.

Pitfalls Besides confusion with both Merlin and Hobby, the identification of Peregrine and other large falcons is complicated by the not infrequent occurrence of falconers’ escapes, such as Lanners F. biarmicus, Sakers F. cherrug, Laggars F. jugger and even hybrids. When faced with an odd falcon, in particular with a possible dark-plumaged Gyrfalcon F. rusticolus, be sure to eliminate these various escapes. A complicated subject: see Forsman (1999).

In recent years there have been a number of reports of juvenile Peregrines resembling the Arctic races calidus (n. Europe) or tundrius (Canada and Greenland). Being a long-distance migrant, the latter is probably a likely vagrant to Britain. Such birds may appear slightly slimmer and longer-winged than nominate peregrinus and show extensive white on the cheeks, a prominent supercilium that curves down the sides of the nape, narrower moustaches and narrow brown underpart streaking on a creamy background. Such birds may suggest juvenile Lanner . The problem, however, is that nominate peregrinus may also produce juveniles that closely resemble these races, so the positive identification of such birds is fraught with difficulty.

Where and when Merlin breeds on moorland, mainly in Scotland, N. England and Wales (and locally in Ireland) but it is more widespread in winter (mostly early September to early April) when there is a more general dispersal and some immigration. It is typically found on coastal and estuarine marshes, but also very sparsely inland, generally in open country.

Flight, structure and behaviour A small falcon, the male being only about the size of a Mistle Thrush Turdus viscivorus, but the female is nearly as big as a Kestrel F. tinnunculus. Compact with sharply pointed but relatively short, angled, swept-back wings and a medium-length tail. This distinctive shape readily separates it from both Hobby and Kestrel. However, when circling, the wings can look quite rounded at the tips. It is most likely to be seen flying low over moorland or coastal marshes with a fast, dashing flight in which the sharply pointed, angled-back wings produce a rather ‘flicking’ flight action. It will sometimes rise to some height and fly at speed towards unsuspecting prey, with the wings intermittently closed-in tight against the body, producing a flight action strongly reminiscent of a fast-flying Mistle Thrush (but note that Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus also does this). When chasing birds at close range, it can be extremely persistent, following every twist and turn of its quarry. It frequently uses prominent perches, such as posts and stones, when the wing-tips fall well short of the tail-tip (unlike Hobby, which has the wings similar in length to the tail).

Plumage Note that all ages show weak moustachial stripes and a dark area on the ear- coverts, so they appear markedly plain-faced compared to Hobby and Peregrine. Adult male Adult males are in the minority and note that they are actually quite rare in southern areas in autumn and winter. Blue-grey above, with a broad, dark subterminal tail-band (some also show narrower dark barring towards the base). The underparts vary from beige to dark orange, with broad brown streaking. Adult female Similar to juvenile (see below) but tends to be greyer above with pale feather fringes producing a somewhat barred appearance. The outer tail feathers (visible from below) are less regularly barred than juvenile. Juvenile Most autumn Merlins seen in lowland Britain are juveniles. They appear neat, with dark brown upperparts and whitish-buff underparts heavily lined with thick chocolate streaks (maybe some barring on the flanks). From above, the primaries, secondaries and tail are heavily barred with buff (unlike Sparrowhawk); the tail shows a noticeable whitish tip. In fresh plumage, the brown upperparts are tinged rufous (a result of rufous feather tips and fringes).

Calls On the breeding grounds, its calls include a shrill, chattering kik-ik-ik-ik and an anxious kee-kee-kee… recalling Kestrel.

Pitfalls Confusable with both Hobby and Peregrine but note that, by October, when most migrant Merlins appear in lowland Britain, Hobbies are rare. A notorious beginner’s bird and claims of Merlins in atypical situations, particularly inland, frequently involve male Sparrowhawks, which occasionally bunch their primaries to produce a pointed wing shape. When hunting, Sparrowhawks may behave like Merlins, flying at speed close to the ground and partially closing their wings in pursuit of prey (note that ‘Merlins’ flying low along the road in front of the car are invariably male Sparrowhawks). Because of these problems, special care is needed when views are brief and a Merlin should not be claimed unless a clear and unambiguous view is obtained of its wing-shape. Note also that, whereas Merlins tend to land on exposed perches, Sparrowhawks usually land in trees. In summer, a less likely confusion species is Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus, which also has sharply pointed wings but is easily separated by its long, graduated tail, pointed head/bill profile and slower, unhurried flight with stiffer, shallower wingbeats.

Where and when A summer visitor from late April to early October, breeding mainly in s. England, with a small number in Wales and a few pairs in Scotland. Like Peregrine, it has increased significantly in recent decades. The largest populations occur in s. England, particularly on heathland, but it also breeds widely in agricultural areas. Large spring concentrations hawk dragonflies over selected southern wetlands.

Flight, structure and behaviour Arguably the most beautiful of our commoner falcons, with a distinctive silhouette: slim, with very long, narrow, pointed, scythe-shaped wings and a shortish to medium-length tail. Its shape can suggest a gigantic Common Swift Apus apus or, when hawking insects low over the water, a Black Tern Chlidonias niger. Far more conspicuous in their aerial feeding behaviour than other falcons, often feeding in loose parties, floating around like sailplanes over heaths, downs, lakes and marshes, twisting and turning as they snatch dragonflies and other insects in their talons, before transferring them to the bill. They also pursue birds and, like Peregrine, spend some time circling to a great height before stooping into flocks of swifts and hirundines, their favoured prey. Note that House Martins Delichon urbicum give an anguished shrill shrip shrip bird-of-prey alarm. It is worth learning this call as it is often the first indication of the presence of a Hobby. Also, feeding Common Swifts (and associated hirundines) will often, in unison, suddenly and silently fly fast and direct in the same direction; when this happens, look behind the moving flock as there may well be a Hobby in pursuit. Although they perch on fence posts and bare branches, they usually land within the tree canopy (unlike Merlin). Like Red-footed Falcon, they will sometimes feed from fence posts in a shrike-like manner.

Plumage Adult Grey above with a heavily streaked white breast and belly; distinctive reddish thighs and vent may ‘flash’ at a distance. Black moustachial stripes stand out prominently against the white face; at close range, it also shows a narrow, short white supercilium. Juvenile Pale brown feather fringes on the upperparts produce a slightly browner appearance than the adult, the rump being browner still; the underparts are buff (heavily streaked dark) and note that the vent and undertail-coverts are also buff, an obvious difference from the adult. Juveniles also show a pale trailing edge to the wing and, more obviously, a whitish tip to the tail. First-summer Some are similar to adults but many are browner on the upperparts, a result of variable amounts of retained, faded, juvenile feathering; also, the vent and undertail-coverts are a pale washed-out orange.

Calls Often quite vocal and calls are useful in locating Hobbies hidden in trees. The commonest call is a distinctive kee kee kee kee kee... distinctly lower, deeper and slightly huskier than Kestrel. It also gives a shrill kerr-it-it in aggressive encounters. Juveniles may give a muffled dry, throaty ick ick.

Pitfalls High-flying Hobbies can be confused with Peregrine but note the latter’s greater bulk and broader wings. High-flying Merlins are often misidentified as Hobbies, but note the shape differences outlined above. Kestrel will, on occasion, also hawk flying insects just like a Hobby, so be cautious when identifying distant individuals.

Where and when A rare spring and summer vagrant (very rare in autumn), currently averaging c. 14 records per year although as many as 125 were seen following persistent easterly winds in the spring of 1992. Most occur in s. and e. England, in similar habitats to Hobby, but it has occurred throughout Britain; very rare in Ireland.

Behaviour Most likely to be found hunting from bushes, telephone wires or fence posts in a rather shrike-like manner, often perching with partially drooped wings, rather like a Cuckoo. Alternatively, they may hunt from the ground, flapping short distances or awkwardly leaping and hopping after prey. They also hawk flying insects like a Hobby. Sometimes remarkably tame.

Flight, structure and shape Similar in shape to Hobby, for which it could be mistaken in a brief view, but the wings are not quite as long, while the tail is longer and more obviously rounded when spread; thus its shape is slightly more Kestrel-like. Flight similar to Hobby but more leisurely, slightly flappier, with perceptibly deeper wingbeats. Unlike Hobby, it persistently hovers, but with noticeably deeper wingbeats than Kestrel.

Plumage Great care is required when identifying poorly seen Red-footed Falcons (particularly ‘fly-overs’), records of which are always carefully scrutinised by records committees. Note in particular that Hobby is superficially similar in shape, and in certain lights it can look uniformly dark below; therefore, it is essential to obtain a good, prolonged look at a potential Red-foot. Four basic plumage types occur here. Adult male Note that this is one of the rarest plumage types to occur in Britain ( c. 15% of all records). Uniformly blackish-grey but, importantly, on the upperwing the primaries and secondaries are always conspicuously pale silvery-grey. Rufous vent and undertail-coverts, bright orange feet, cere and eye-ring. First-summer male This age occurs much more frequently than adult male. It has a variable body moult in its first-winter but the juvenile flight feathers and tail are retained as are, usually, most of the juvenile greater coverts. It therefore lacks the strong silvery-grey colour of the adult male’s upper-primaries and secondaries. It shows obvious traces of immaturity as follows. 1 An off-white throat and orange coloration on the sides of the neck and upper breast (exact colour individually variable). 2 A strongly-barred juvenile tail. 3 Juvenile barring on the greater coverts and tertials. 4 Heavily barred juvenile underwings. 5 Orange-yellow legs, cere and eye-ring. Since most first-summer males have a paler throat/upper breast, this age/sex is that most likely to be confused with Hobby. Adult female Perhaps more likely to be passed off as a Kestrel, but the underparts and crown are orange-buff, sometimes strikingly dark. It has a prominent black ‘highwayman’s mask’ around the eye (extending into a short moustache) and a partial white collar that extends around the neck-sides towards the nape. The mantle and wings are blue-grey, barred dark grey. Both the tail and the under-primaries/secondaries are barred, with noticeable dark tips to the under-primaries. The underwing-coverts are conspicuously orange-buff (although this colour may be restricted to the leading coverts). Eye-ring, cere and legs orange or orange-yellow. First-summer female Far more likely to be seen than adult female (see ‘first-summer male’ above for an outline of first-winter moult). Separable as follows: 1 Streaked on the crown and nape (plain on adult). 2 Larger dark face mask. 3 Streaked below (little or no streaking on adult). 4 Noticeably browner above, with plain outer greater coverts (barred on adult); the rump and barred tail may look quite pale when spread (almost sandy). 5 Underwings entirely barred. Beware of confusion with browner first-summer Hobby. Juvenile This age and plumage is extremely rare in Britain. Surprisingly similar to juvenile Hobby, but buff and rufous feather fringes make it scalier above. It has an obviously barred tail (barring is confined mainly to the inner webs on Hobby, so is not readily apparent when viewed from above). It also has a paler forehead and forecrown with a dark ‘highwayman’s mask’ and a short moustache; also a more extensive white collar around the neck-sides. Streaking on the underparts is not usually as heavy as on juvenile Hobby.

Pitfalls Besides Hobby (outlined above) another pitfall with males is melanistic Kestrel. The bird portrayed on p. 131 is loosely based on one such individual seen near Cardiff in July 1986. It had a blackish head and underparts and very dark upperparts, but it was easily identified at rest by the wing/tail ratio (on Kestrel the wing-tips fall 1–2cm short of the tail-tip, on Red-foot they project c. 0.5cm beyond); in addition, it showed typical Kestrel bare-part colours, it lacked the rufous vent and undertail-coverts of Red-foot, and showed traces of barring right across the upperparts.

An extreme vagrant with just one British record (Yorkshire, September–October 2008). However, possibly overlooked. Very similar to Red-footed Falcon but adults are easily separated by their unbarred gleaming white underwing-coverts. First-years do not show white until it gradually appears during the autumn moult into second-winter plumage. Any Red-foot showing obvious white on the axillaries and underwing-coverts should be photographed and expert assistance obtained.

Reference Forsman (1999).