Where and when Ringed Plover is a widespread breeding and wintering bird (mainly coastal) with numbers greatly inflated in spring and autumn by passage migrants (mainly Greenland breeders); also occurs inland on migration, sometimes in reasonable numbers if water levels are low. Little Ringed Plover is a relatively recent colonist (first bred in 1938) but is now a widespread summer visitor, with more than 900 pairs in a 2007 survey. Although associated with English gravel pits, it has now spread on to rivers in Wales and Scotland. It occurs more widely on migration, from March to May and June to September. A former breeder, Kentish Plover is now a rare migrant, currently averaging 25 records a year, mainly on south and east coasts; it is very rare elsewhere and is unlikely to be seen inland.

General features Little Ringed Plover is smaller and slimmer than the dumpy Ringed Plover, with a distinctly more attenuated and tapered rear end. These differences are very obvious when the two species are together. In flight, the best distinguishing feature is Little Ringed’s lack of a wing-bar: Ringed has a conspicuous broad white bar, whereas Little Ringed shows at best only tiny pale tips to the greater coverts, which are very difficult to detect in flight.

Calls Totally different: Ringed gives a soft, mellow poo-ip, with an upward inflection, whereas Little Ringed gives a thin, abrupt, rather whistling tee-u, inflected downwards.

Songs Both have a slow, bat-like display flight. Ringed Plover’s song is a musical tuluwee tuluwee tuluwee… (snatches sometimes given in winter). Little Ringed gives a fast, pulsating pre-pre-pre-pre… and also a high, rolling arrreeoo…arrreeoo…

Plumage and bare parts Adults At rest, Little Ringed has dull horn or flesh-coloured legs and a fine black bill. In contrast, summer Ringed Plover has bright orange legs and a stubby black-tipped orange bill; winter bare-part colours are much duller. Further differences include Little Ringed’s obvious yellow orbital-ring (conspicuous in breeding condition) and much narrower breast-band. Female Little Ringed often has extensive brown feathering on the otherwise black ear-coverts and are generally duller and less smart than the males. Winter adults of both species have the blacks duller and browner. Juveniles Juvenile Ringed Plovers may appear obviously darker and more ‘chocolate’ looking than accompanying adults, with yellowish-green, not orange legs. When identifying juvenile Little Ringed at rest, concentrate on the head: unlike Ringed, the forehead is buff, often golden-buff, merging gradually with the rest of the crown; the buff supercilium is faint or virtually lacking, and the ear-coverts are more or less concolorous with the crown. All this combines to produce a distinctive hooded effect, which Ringed Plover lacks; there is also a fine, inconspicuous pale orbital-ring. Juvenile Ringed Plover has a clear-cut white forehead and supercilium, and darker ear-coverts, producing a far more contrasting pattern. Like adults, juvenile Little Ringed has a narrower breast-band, while the paler, sandier upperparts may be surprisingly obvious when the two species are together. Very fresh juveniles have golden fringing to the upperparts, which quickly fades to buff.

Size, structure and behaviour Intermediate in size between Ringed and Little Ringed, but with rather a front-heavy ‘chick-like’ shape (much less attenuated at the rear than either Ringed or Little Ringed). It may appear rather long-legged, particularly when the plumage is sleeked down in hot weather. Tends to be rather active, often running along the beach like a Sanderling Calidris alba.

Call Migrants give a rather soft, Sanderling-like tip or fwit, occasionally sounding rather more metallic; sometimes a faintly disyllabic ki-kip.

Plumage Individuals of all ages are easily identified by their pale sandy plumage (much paler than Ringed Plover), blackish or dark grey legs, fine black bill and narrow patches confined to the breast sides. Females and juveniles are pale sandy-brown and white, juveniles having pale feather fringes and a less well-defined head pattern; on both, the black eye and black legs stand out from the pale plumage. By late summer, males attain female-like winter plumage, but close scrutiny usually reveals slightly darker breast patches and eye-stripe. Males acquire breeding plumage early, and by the New Year they are rather dandy with neat black breast patches, a thick black eye-stripe and a black forecrown bar. The rear crown is variable, but most males show at least some bright cinnamon-orange coloration and some have the whole rear crown this colour and are very striking. In flight, Kentish shows a narrow white wing-bar (narrower than Ringed) and white sides to the tail.

A very rare North American vagrant (three records to 2012) but probably overlooked. Very similar to Ringed Plover but most likely to be located by its distinctive call: a markedly disyllabic upslurred ch-wee, reminiscent of Spotted Redshank Tringa erythropus. Detailed examination of the bill, head and feet would then be required (and photographs essential).

Where and when A common coastal winter visitor and passage migrant, some remaining throughout the summer; small numbers occur inland on passage and in winter.

Structure A large, bulky, rather hunched, long-legged plover with a large black eye and a hefty, thick, blunt bill; the latter is particularly useful when separating distant individuals from European Golden Plover.

Flight identification and call A large, grey plover with a prominent white wing-bar that contrasts with the black primaries and primary coverts. Easily separated from Golden by its square white rump and prominent black axillaries, which contrast strongly with the white underwing-coverts. The call is diagnostic: an evocative clear, mournful whistle: wee-oo-eeeee.

Plumage General Compared to Golden, Grey Plover is a pale, colourless, grey-and-white wader, but note that juveniles are distinctly buffier. If in doubt, wait until it flies. Adult summer Easily identified by blackish upperparts, spangled with white (lacking the yellow tones of Golden), a striking white forehead and a supercilium that runs down the sides of the neck and bulges on the breast-sides. The underparts are black, but with a white rear belly and undertail-coverts. In full plumage, females are slightly browner below and show white feathering within the black. First-summers remain in their winter quarters and do not acquire full breeding plumage; they may become very bleached and worn. Juvenile Distinctive, but also potentially confusing. Fresh plumage is immaculate: grey-brown above, neatly and beautifully spangled with pale yellow. The underparts may also look smoothly and uniformly pale yellowish-buff, but closer views reveal delicate breast streaking. The pale yellow tones may provoke confusion with Golden Plover or, especially, American Golden. Compared to the latter, Grey has a browner crown, a less distinct supercilium and an obviously larger bill. Note, however, that the yellow tones soon fade to whitish as autumn progresses. Winter Essentially a pale grey plover with diffuse whitish upperparts spotting and fringing, and a mottled grey upper breast. It has a subdued supercilium and a darker patch through the eye.

Where and when A familiar farmland species in winter (abundant in some areas) and also breeds on moorland in upland areas of n. and w. Britain, as well as in Ireland. It occurs on passage in a wide variety of habitats, and in winter will feed and roost in more saline environments.

Structure A medium-sized plover, similar in shape to Grey, but slightly smaller and stockier with a narrower, weaker bill.

Flight identification and calls Distinctly yellowish-brown in overall plumage tone. Looks rather uniform above, lacking Grey’s white rump. The wing-bar is less conspicuous, confined mainly to the bases of the primaries. The underwing-coverts are silvery-white, lacking Grey Plover’s prominent black axillaries. It forms large and impressive flocks, often with Lapwings Vanellus vanellus. Golden Plovers tend to fly at some height, bunching together and flying fast and direct, their underwings flashing white from a distance. From below, the wings look long, narrow and pointed. Easily identified by call: a soft, rather mournful too-lee or tloo, unobtrusive yet distinctive, and peculiarly evocative of frosty winter mornings. The calls vary both in length and composition, and large flocks are noisy and conversational. On the breeding grounds, the male sings a beautiful, mournful poo-wee-oo (rising on the middle syllable).

Plumage Easily identified by its obviously brown-and-yellow plumage tones. Adult summer Varies according to range (with much individual variation). Northern individuals acquire more extensive summer plumage and are completely black from the face to the belly, with a broad white supercilium extending down the neck-sides, broadening on the breast-sides before continuing down the flanks to the vent/undertail-coverts. Southern birds are greyer and more mottled on the face and throat, with black only in the centre of the belly; consequently, the white on the sides of the neck and breast is more extensive. The upperparts are strongly spangled with yellow. Winter and juvenile Blackish upperparts are liberally spangled dark yellow, while the dingy underparts have a streaked/mottled yellow-buff breast and flanks, and a whiter belly. Tends to look rather plain-faced with a large black eye; the supercilium is ill-defined and subdued (although stronger on some) and there is a dark patch on the rear of the ear-coverts. Adult winter and juvenile plumages are very similar, but autumn juvenile is neater, slightly more streaked on the breast and slightly greyer on the belly.

General These two species were formerly lumped together as ‘Lesser Golden Plover’ and the old name provides the first clue to their identification. Both are distinctly smaller and slighter than European Golden. The key feature on which to concentrate is the underwing. Whereas European Golden has pure white underwing-coverts and axillaries, both American and Pacific are grey in this area. When separating these two vagrants from each other, their occurrence patterns are also relevant. Whereas American tends to occur in the same kind of dry habitats as European Golden, Pacific is usually encountered in the same type of saline environments as Grey Plover. In addition, whereas most Americans occur in autumn (mainly juveniles) most records of Pacific relate to summer-plumaged or moulting adults in late summer (July/August).

Where and when An annual vagrant, currently averaging 16 records a year. Most are juveniles in northern and western areas in September/October, but adults and first-summers also occur in spring and late summer, often on the east coast. Very rare in winter.

Structure In direct comparison, American is smaller, slimmer and proportionately taller looking than European ( c. 80% its weight). When active, it often appears very slim, sleek and attenuated, with a small head, long neck and slim, rather pear-shaped body and long legs; consequently, it usually looks more upright and rather gangly. European usually looks quite fat and rounded in comparison but, when resting, the two species can appear more similar. The most obvious structural difference is that American has long primaries that extend in a scissor-like manner well beyond the tail. Equally important is the relative length of the exposed primaries in relation to the overlying tertials. On American, the primary projection is approximately equal in length to the overlying tertials, whereas on European it is about one-quarter the length (about three-quarters on juvenile Grey Plover, usually shorter on adults). Also, the tips of the tertials on American fall well short of the tail-tip, whereas on European they fall closer to the tip itself (but note that some Europeans show shorter tertials). American’s long-winged appearance is related to the fact that many undertake a huge trans-oceanic migration over the w. Atlantic to wintering grounds in s. South America.

Behaviour Unlike most Europeans, often very tame. When feeding, it pivots forward at nearly 45 degrees, whereas European tips its body much less obviously, simply reaching down with its head and bill.

Flight identification Similar to European Golden but, in direct comparison, obviously smaller and slighter with shorter, narrower wings. Most important is a dull and dusky underwing: the lesser and median coverts and axillaries are quite dark grey (silvery-white on Golden) with the greater coverts and remiges paler grey. The wing-bar is also pale grey (white on European).

Calls See below.

Plumage At all ages it is greyer, less yellow than European. Adult summer Note that American Golden usually retains much of its summer plumage until arrival on its winter quarters, so autumn adults are often conspicuous amongst winter adult or juvenile Europeans; consequently, any ‘Golden Plover’ in autumn showing obvious traces of summer plumage is always worth a second look. In summer plumage, adult American has more extensive black on the underparts than European, males being solidly black right down to the undertail-coverts. A smartly contrasting area of white extends from the supercilium, down the neck-sides, bulging prominently onto the sides of the breast. Females, however, may be less solidly black below, while moulting birds usually display a patchy mixture of black and white. Like juveniles, summer Americans are greyer and less colourful above, although closer views reveal fine but extensive pale yellow notching across the back and scapulars. Late autumn adults are more faded, such birds often looking worn and very ‘monochrome’ (sometimes lacking all yellow tones). They then show a striking thick white supercilium and a solid black cap, delicate spangling and fringing across the upperparts and patchy black underparts. Juvenile Once they lose their summer plumage, European Golden Plovers are not easy to age, winter adults and juveniles both appearing rather coarsely patterned and distinctly yellowish. In comparison, juvenile Americans appear cold, grey and colourless. Their upperparts are delicately spangled with buff or white, but they lack the strong yellow tones of European (but may appear yellower on the rump); their buff underparts are paler and plainer, immaculately streaked and mottled with grey (lacking European’s stronger breast-band). Most distinctive is a prominent whitish supercilium that contrasts with a dark crown, the latter producing a capped effect. Front-on, they can look strikingly white-faced (obvious also in flight). Winter Remember that, unlike European, late autumn individuals may retain strong traces of summer plumage. In full winter plumage, it has an obvious white supercilium and capped appearance, but the upperparts are plainer and greyer with the spotting more diffuse (many feathers are fringed rather than notched). The underparts are whiter, diffusely mottled and shaded with pale grey. Its plumage is less neat than juvenile and plainer when worn. First-summer Acquires very little summer plumage until late April (O’Brien et al. 2006), appearing ‘winter-like’ before then: dull, colourless, worn and often rather messy across the upperparts. Consequently, spring vagrants show variable but often only limited amounts of black feathering on the underparts, the white supercilum and general greyness then being the most obvious differences from European. Some remain on their wintering grounds and acquire very little summer plumage.

Pitfalls Double check that any potential juvenile American is not a juvenile Grey Plover (see Grey Plover). Note also that very grey Golden Plovers occasionally occur, so it is essential to check not only the plumage features, but also the structural differences and the underwing.

Where and when A very rare vagrant, currently averaging three records a year. Most are adults in July and August, mainly in the Northern Isles and on the east coast. Records have, however, occurred in most months, but it is very rare in winter. As with all vagrant e. Palearctic waders, juveniles are peculiarly rare. Most occur in saline habitats, whereas American tends to occur in fields and freshwater environments.

Structure Breeding as it does in Siberia, between European and American Golden Plovers, Pacific is intermediate in appearance. It is useful to think of it as being structurally similar to American but with plumage more similar to European. By weight it is the smallest of the three golden plovers. Being c. 60% the size of European, it looks noticeably smaller, slighter and proportionately longer-necked and longer-legged; it can look quite thin and lanky, particularly in hot weather with the plumage sleeked down. Note that photographs often show Pacific with very long legs (with long, exposed tibia) but many of these are taken in the Far East where hot weather induces feather-sleeking; vagrants at cooler latitudes appear more fluffed-out and, consequently, shorter-legged. Compared with American, it tends to look longer-legged, rounder-bodied and perhaps longer-necked, making it look somewhat front-heavy when feeding; it also has a longer bill. Its primaries do not project beyond the tail in the same scissor-like manner as American. It is much more similar to European in this respect, the exposed primaries being only about one-quarter to half the length of the overlying tertials (equal on American). Also, whereas the tertial tips fall well short of the tail-tip on American, they fall much closer to it on Pacific.

Flight identification Appears similar to European Golden, but smaller and slighter. Most importantly, the underwing-coverts and axillaries are dusky-grey, like American (white on Golden). The feet project beyond the tail to produce a more attenuated rear end, more so than both American and European.

Calls See below.

Plumage Its plumage is yellower than American, being similar to European. Adult summer Pacific is similar to ‘Northern’ European Golden Plover, being yellowish above (although perhaps more coarsely patterned). Compared to American, the white supercilium, neck and breast stripe bulge less prominently into the breast-sides; also, the white extends narrowly right down the flanks, where it becomes rather messy due to the intrusion of a certain amount of black feathering (note, however, that some female Americans and also moulting late summer males may be similar in pattern). Although variable, like American the black extends from the belly onto the vent and undertail-coverts but only rarely are the undertail-coverts completely black. Juvenile In overall appearance, juvenile Pacific suggests a small, slim, long-legged, gangly, front-heavy European Golden Plover with grey underwings and axillaries. Its plumage is quite different from juvenile American, being yellower and more coarsely patterned (therefore, much more similar to European). Pacific also differs from American by its more subdued facial pattern, showing a less obvious supercilium and capped effect (face and supercilium yellower in tone). Adult winter Unlike European, many retain traces of summer plumage into early winter. The upperparts are brown with old feathers showing whitish feather notching and fringing. Any new feathers, particularly on the scapulars, have noticeably yellow notching or fringing. The supercilium is more prominent than European and, unlike American, both it and the face may show a distinct yellow tone. First-summer As American Golden, there is a variable body moult in their first spring. Some acquire summer plumage by early May, but others acquire only partial summer plumage, while others retain winter-type plumage, the latter usually remaining behind on the wintering grounds (O’Brien et al. 2006).

Hybrids Presumed hybrids between European Golden and Pacific Golden have occurred. One seen in Somerset superficially resembled Pacific but had white axillaries and underwing-coverts (Vinicombe 1988). It is, therefore, essential to check for such anomalies when faced with a potential Pacific Golden Plover.

Calls Although American and Pacific may sound noticeably different from European, separating them from each other is much more difficult, particularly since they have a variety of calls with which most European observers are unfamiliar. Although similar, it is their quality and delivery that are different. American sounds slower and squeakier, Pacific quicker, more cheerful and more urgent. The latter’s ‘Spotted Redshank Tringa erythropus call’ is perhaps the most distinctive. American Golden Gives a rather slow, upslurred tu-wee (sometimes down-slurred), strikingly shrill and squeaky compared to European Golden, being higher-pitched, less mournful and less haunting; it can also give a ‘thicker’ more urgent version of this: che-wit. Also a more mournful t-wee-oo (emphasis on the middle syllable) which may recall a squeaky swing. Pacific Golden Gives a mellow but quicker, more cheerful, more urgent tu-weet or chu-wee, again with the second syllable upslurred, or a tu-wee-u (the second syllable upslurred and the third simply an insignificant lower-pitched add-on). It also gives a quicker, more energetic tu-ick or chu-it that sounds like a quick Spotted Redshank Tringa erythropus, but fuller and mellower.

Where and when Breeds almost exclusively in Scotland (500–750 pairs during a 1999 survey) but occurs more widely on migration, often on hilltops and moorland, or in coastal fields; in some areas, small flocks may appear annually in the same favoured fields.

General features Smaller and stockier than the previous four species and easily separated, particularly in summer plumage. Unlike the three ‘golden plovers’, its legs are pale: yellow or yellowish-brown. It is often very tame, but larger flocks may be more timid. Often hunkers low to the ground when ‘spooked’.

Flight identification Resembles a small Golden Plover and looks similarly narrow-winged. High overhead, it may not be readily identifiable if its smaller size is not apparent. The upperwings and rump are plain, but the tail is noticeably blacker, with white right around the edge. The leading underwing-coverts are white, the greater underwing-coverts and remiges pale grey.

Calls The flight call is a low, rolling, downward-inflected guttural purring prrrrr, rather odd but distinctive (a quiet version is sometimes given on the ground). The contact call in flight is a subtle, rather abrupt, soft, plaintive, slightly mournful pyoo, vaguely resembling an abrupt European Golden Plover.

Plumage As their sexual roles are reversed, females are brighter than males. Adult summer Easily identified. At all ages has stunning, broad white supercilia, starting above the eyes and meeting in a V on the back of the head. In summer, these are offset by a dark brown crown and a dark line through the eye. The throat is white but the upper breast is grey, separated from the orange underparts by a narrow white band across the breast. The belly is blackish on females, duller on males. The upperparts are brown, with buff feather fringes. Females are very bright, but males are duller both on the crown and below, and some may be difficult to sex. Juvenile The vast majority of autumn migrants in Britain are in juvenile plumage. Immaculate and rather buff-looking. Prominent creamy-buff or golden-buff supercilium, strongest from the eye back, contrasting with a blackish crown. The underparts are golden-buff, with fine dark grey streaking and mottling across the upper breast, a narrow pale band on the lower breast, which in turn is bordered below by a dark band of diffuse grey mottling. Blackish-brown upperparts are prominently spangled whitish. Winter Similar to juvenile but duller and browner, and the grey-brown upperparts are fairly plain, showing chestnut or buff feather fringes, not notches.

References O’Brien et al. (2006), Pym (1982), Vinicombe (1988).

Where and when Little Stint is a rather scarce passage migrant, mainly from late April to early June and from July to October. Numbers of autumn juveniles vary annually, with late August to early October being the peak time; a few winter, mainly in s. England. Temminck’s Stint is a much rarer migrant, currently averaging 120 a year, with a peak of 309 in 2004. It occurs mainly in May and August/September, mostly in e. England; it occasionally breeds in Scotland and very rarely winters. Sanderling is a winter visitor to sandy coastlines, but larger numbers of Greenland migrants pass through western areas mainly in May and July–September; small numbers occur inland on migration (and occasionally in winter, particularly during freezing weather).

General features A tiny wader, whose small size should always be apparent, even if no other species are present for comparison. It has quick, energetic, rather jerky feeding actions, but at other times can be slower and even plover-like. It is often prone to fast, Sanderling-like runs. A dumpier, longer-legged and more upright bird than Temminck’s. The primaries are usually rather long, extending well beyond the tertials and just beyond the tail, forming quite a pointed rear end (which is often angled upwards when feeding, emphasising this pointed impression). Note, however, that on adults in particular, the primary projection is variable, with some showing a much shorter projection. The short bill easily separates it from Dunlin C. alpina and the black legs are an important difference from Temminck’s. It looks very small in flight and is easy to pick out among Dunlin flocks.

Call An unobtrusive yet distinctive tip or tip tip tip.

Plumage Adult summer A bright and well-patterned stint compared with Temminck’s. In spring, their overall plumage tone is very variable, mainly because fresh migrants have delicate whitish fringes to their new summer-plumaged head, breast and upperpart feathers; these produce a pale whitish-grey or ‘frosted’ look. However, these fringes soon wear away to reveal a much more colourful, rich buff or chestnut appearance, the strong chestnut tones being an important distinction from Temminck’s (and also the rare Semi palmated Sandpiper C. pusilla). The breast-band is strong but also variable, buff to chestnut, delicately mottled blackish and usually fading to white in the middle. Pale edgings to the mantle usually form a V when viewed from the rear, but this is rarely as obvious as on autumn juveniles. It has a variable supercilium and an important feature of Little Stint in all plumages is that it subtly forks on the crown, just before the eye (most other stints lack this faint ‘upper supercilium’). Behind the eye is a variable buff-brown to chestnut ear-covert patch (with a narrow white eye-ring). Note also that, at a distance, summer-plumaged Little Stints can look rather uniform, thereby prompting confusion with Temminck’s. Returning autumn migrants in July and August are much more worn, having lost all traces of their grey spring ‘frosting’. Again, they are very variable, many showing a messy mixture of black, buff and chestnut on their upperparts as well as a fairly obvious mantle V. However, heavily worn individuals look much blacker above, the more colourful buff and chestnut tones having largely worn away and/or faded to whitish. Some can, therefore, look quite black, buff and white in overall plumage tone. The acquisition of their first grey winter feathers can reinforce this impression of drabness. Winter The upperparts become uniformly pale grey but each feather shows a noticeable black line down the centre and this often extends either side of the shaft to form a narrow, pointed black wedge; on better-marked individuals, this produces a distinctly patterned impression, even at a distance. The breast-sides are also grey, mottled darker. It has an indistinct supercilium (with a split supercilium effect visible in closer views). Some, presumably first-winters, may also retain a hint of a paler mantle V. Some acquire winter plumage by late summer, and the presence of such grey individuals among the more familiar juveniles often perplexes the inexperienced. Juvenile Most autumn Little Stints, from mid August onwards, are juveniles. They are immaculately patterned with golden, chestnut and buffish feather fringes (strongly rufous-fringed on the upper scapulars at least). Most distinctive is the characteristic white V down the sides of the mantle, formed by pale feather edgings. The crown and ear-coverts are also rich buff, with a white ‘split supercilium’. The underparts appear very white, with shading and diffuse streaking confined to a patch on the breast-sides. By late autumn, juveniles fade considerably and look much greyer, particularly when their first grey winter feathers appear; also, the white mantle Vs gradually become much less obvious. Note that a minority begin body moult by early September, some virtually losing their white mantle Vs and becoming very drab on the mantle. The overall appearance of such birds may suggest Semipalmated Sandpiper C. pusilla (see Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla).

General features An unobtrusive, secretive stint that is easily overlooked. Occurs almost exclusively in freshwater habitats. Tends to be rather solitary, creeping around on flexed legs in a slow, furtive, mouse-like manner (although it can be more energetic). The body looks long, low and horizontal and, unlike Little Stint, the tail projects beyond the primaries to produce a rather attenuated rear end. Compared to Little Stint, the plumage always looks dull and plain, and at all ages its general appearance recalls a diminutive Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos. The head and upperparts are dull brownish-grey with an obvious and well-defined breast-band. The head is relatively plain but shows traces of a faint supercilium and a distinct but narrow pale eye-ring. The key feature is leg colour, which varies from yellowish through greenish-yellow and olive-green to brown (always black on Little Stint, but beware of the effects of mud staining). The flight is fast and twisting on swept-back wings and a flicking action, perhaps recalling a hirundine at a distance; it frequently towers when flushed. Pure white sides to the tail can be obvious on take-off or landing, but frustratingly difficult to see in normal flight. These are a feature not shared by any other Calidris.

Call Completely different from Little Stint: a soft, fast, mouse-like trill si-si-si-si-si that can be surprisingly loud at close range, perhaps sounding more like prrrrooooip. Note that Little Stint sometimes strings several tip calls together, but the sound is harder, drier and quite different.

Plumage Adult summer Pale brownish-grey above, close views revealing black feathering on the scapulars, often forming a band. The black feathers are edged with buff or chestnut. Winter Similar to summer, but plainer and greyer, lacking the black scapular feathering and obvious pale fringes to the wing-coverts. Juvenile Similar to winter but, at close range, the upperparts are neatly fringed black and buff, producing fine, delicate and subtle scaling. It may show small black centres to the rear scapulars, forming a slight dark V when viewed from behind.

General features Although quite different from the previous two stints, Sanderling does, nevertheless, recall an oversized stint. This is mainly because, unlike Dunlin, it has a relatively short black bill. The traditional image of Sanderling is of a very pale hyperactive ‘clockwork toy’ chasing the waves up and down the beach. In such circumstances, it is easily identified but, in its less familiar summer and juvenile plumages, the species can prove far more confusing. This is particularly the case if seen out of context at, for example, an inland reservoir. In such ‘atypical’ situations it may be far more lethargic (although still prone to running off at speed). Easily identified in flight by its very broad white wing-bar (much broader than Dunlin). Winter Sanderling looks very pale in flight. Unlike other waders, it lacks a hindclaw (close-range views are required to establish this).

Call A hard, dry, monosyllabic kik or pit.

Plumage Winter In its most familiar plumage, it appears rather white-headed with very pale grey upperparts and contrasting black bill and legs. It often shows an obvious blackish area at the bend of the wing, but this may be concealed by adjacent overlapping breast feathering. Adult summer A body moult into summer plumage starts on the wintering grounds, so spring migrants, which are commonest in May, are in very fresh summer plumage. Two distinct types occur in spring. Many appear ‘cold and frosty’ in tone, all the small feathers of the head, breast and upperparts having black centres with broad white fringes, producing profuse but delicate black-and-white mottling. The scapulars and wing-coverts have black centres but they too have white fringes. Some retain a few winter feathers mixed-in. There may be a slight chestnut tone to both the ear-coverts and scapulars. As the spring advances, the white fringes wear away to reveal rich chestnut on the feather bases, so later birds are often strikingly chestnut-brown on the head, upperparts and breast-band, appearing rather stint-like as a consequence. There is, however, considerable individual variation and some look distinctly two-toned: predominantly grey on the head and mantle, but chestnut on the scapulars and wing-coverts. Returning adults reappear in July–August, by which time many have become severely worn, faded and rather messy, with winter plumage often starting to appear. Such birds may again appear rather ‘frosty’ and colourless, lacking the strong chestnut tones of late spring. Juvenile Immaculate and quite unlike both adult summer and winter. The entire mantle and scapulars are black, with heavy white spotting that produces a beautifully spangled appearance to almost the entire upperparts. The crown is also black (spangled white) but the face and underparts are predominantly pure white, lacking summer adult’s breast-band; instead, a small area of shading and streaking is restricted to the breast-sides. This plumage is lost in the autumn body moult.

Reference The identification of stints, including the rarer species, is very thoroughly dealt with by Grant & Jonsson (1984).

Where and when Semipalmated Sandpiper is an annual vagrant, currently averaging three or four records a year. Most are storm-driven juveniles in September–October, mainly in western areas, with a few summer adults in July–August (sometimes on the east coast) and also the occasional spring bird. Western Sandpiper is a great rarity (eight records to 2011). Again, there have been juveniles in September–October, a few adults or first-summers in late summer and a single spring record. Both species have also wintered.

Juvenile The first step is to separate ‘Semi-p’ from Little Stint C. minuta. The most obvious initial difference is that juvenile Semipalmated is much duller, colder, greyer and more uniform, appearing grey-buff or grey-brown above, lacking both the rich rusty tones and the white mantle Vs of juvenile Little Stint. The following are the main features to check. 1 UPPERPARTS Juvenile Little Stint has well-patterned upperparts, the most distinctive feature being the characteristic white mantle Vs (two white lines down the sides of the mantle). Two less well-defined white lines are also present on the tips of the second row of scapulars. The rest of the upperparts are black and brown, the individual feathers showing a mixture of white and rich buff or strong rusty fringes. To all intents and purposes, Semipalmated lacks white mantle Vs (it may show just a faint pale line down the sides of the mantle), while the regularly patterned upperparts are duller and browner, a consequence of paler and colder-toned feather fringing. The overall impression is much more uniform than Little Stint; their upperparts are in fact reminiscent of juvenile Curlew Sandpiper C. ferruginea, with similar neat scalloping. One specific feature shown by Semipalmated is the presence of black anchor-shaped markings on the lower scapulars and greater coverts, which Little Stint lacks (it has heavier, more diamond-shaped marks). These take the form of a thick black shaft streak at the base of the feather, which broadens into a black anchor shape towards the tip (although there is some variation in the precise shape). Early-moulting juvenile Little Stints A significant pitfall to bear in mind is that some juvenile Little Stints commence their post-juvenile body moult by early September, with advanced individuals acquiring first-winter mantle feathers as early as mid September. Such birds appear very drab on the upperparts and lack white mantle Vs, so they bear a strong resemblance to juvenile Semipalmated. If in doubt, such birds appear to be more lined on the mantle than ‘Semi-p’ (rather than scalloped) and may show a hint of a paler V; check also structural differences, particularly the primary projection (longer on Little Stint) and foot-webbing. By October, such drab greyish birds inevitably become much more frequent, so particular caution needs to be exercised in late autumn. 2 HEAD PATTERN Semipalmated has a uniformly streaked forehead and crown, producing something of a capped effect (it lacks the obvious ‘split supercilium’ of Little Stint). Below this, a white supercilium extends back from the bill, narrowing over the eye and then flaring at the rear. A dark line extends from the bill back across the lores, through the eye and fans out behind the eye to form an ear-covert patch which is often clear-cut and well defined. Another important point is that the eye shows a narrow but quite noticeable white eye-ring, most of which is contained entirely within the ear-covert patch. This head pattern gives Semipalmated a characteristic facial expression that is very distinctive once learnt and is subtly but distinctly different from that of Little Stint. The latter has a fairly white forehead, a ‘split supercilum’ (the supercilium splits so that there is a narrow ‘upper supercilium’ forking up into the sides of the crown) and a much weaker and more diffuse area behind the eye that fails to form a discrete and solid ear-covert patch as it does on Semipalmated. 3 BILL Little Stint’s bill tapers to a relatively fine tip, whereas Semipalmated’s is slightly thicker at the base and is relatively broad right down to the rather blunt-ended tip (close views may reveal slight lateral broadening at the tip). This creates a characteristic ‘tubular’ impression. Many Semipalmated have relatively short and rather thick-based bills, but note that some eastern females are much longer-billed (see below). 4 UNDERPARTS Little Stint has an area of rather diffuse streaking on the breast-sides, whereas Semipalmated tends to show a patch of more neatly defined, crisper streaking. 5 PRIMARY PROJECTION Little Stint has a long primary projection which, surprisingly, is about half to two-thirds the length of the overlying tertials. Semiplamated’s primary projection is much shorter, perhaps approaching one-third of tertial length at a maximum (but some larger females can apparently show a longer projection). Most have the primaries projecting only slightly beyond the tertial tips and some have their primaries virtually covered by them. Consequently, Little Stint looks significantly longer-winged (often with quite a pointed rear end at a distance). 6 CALL Little Stint gives a quiet, insignificant tip or tip tip. Semipalmated has a soft, thin, slightly more rolling call, variously transcribed as cherk, chlip, chip or prip, distinctly softer and less penetrating than that of Little Stint. It is sometimes repeated in quick succession. 7 SIZE AND STRUCTURE Semipalmated is slightly larger, bulkier, more ‘hump-backed’ and longer-legged than Little Stint, but these differences are minor and they are, of course, much less apparent in the absence of a direct comparison. 8 PALMATIONS As its name suggests, Semipalmated shows palmations (tiny webbing) between its toes, which Little Stint lacks (this is strongest between the middle and outer toe). In the field, the angle between the toes therefore looks rounded, whereas it appears pointed on Little Stint. It must be stressed that close views are required to see this, preferably with the bird front-on and on dry, unvegetated ground. Beware of the effects of mud between the toes.

Adult Adults do not normally occur here in late autumn; instead the few that turn up are much more likely to be encountered in July and August. Adult Semipalmateds at this time resemble juveniles in that they are dull, cold and rather colourless, but they appear greyish, rather than brownish – in fact they lack any strong brown tones to their plumage. In consequence, they often give the impression of being in winter plumage rather than summer, but careful scrutiny reveals that their head, breast and upperparts are in fact heavily patterned. Unlike adult Little Stint, which is quite a rich rufous-brown in summer, late summer adult Semipalmated is essentially a cold, greyish-toned bird, because the black upperparts feathering has pale buff or white fringing. The breast is finely streaked black on a cold whitish background, petering out towards the centre, and the head pattern is similar to that of juvenile, having a uniformly streaked crown (with no split supercilium), a well-defined ear-covert patch, a narrow pale eye-ring and a whitish supercilium. Like the juvenile, it does not usually commence its moult into winter plumage until arriving on the wintering grounds, although a few grey feathers may start to appear in the upper scapulars by mid August (these have a fine black ‘hair-line’ central shaft-streak, rather than Little Stint’s thicker, more diffuse black central streak).

Juvenile 1 STRUCTURE Although Western is traditionally viewed as a confusion species with Semipalmated Sandpiper, it shares many of its characters with Dunlin. In fact a useful aide-mémoire is to think of Western not as a ‘long-billed stint’, but as a ‘miniature Dunlin’. It has a similar shape to Dunlin, being slightly longer-legged, more upright, larger-headed and flatter-backed than Semipalmated, but the most obvious similarity is its bill, which often appears slightly downcurved. Although quite thick at the base, it is quite long and tapers to a fine tip. This is fundamental to its separation from Semipalmated which, as stated above, has a rather thick, blunt-ended, ‘tubular’ bill. It must be stressed, however, that the bill is longest on females and shortest on males, so that some male Westerns show shorter bills than some female Semipalmateds (this is where the shape of the bill becomes important). Like Curlew Sandpiper C. ferruginea, Western also has the habit of wading into deep water and immersing its head below the surface to feed. It is thus less typically ‘stint-like’ than Semipalmated. 2 UPPERPARTS Much more colourful than Semipalmated, with two lines of bright rufous-fringed upper scapulars that contrast with the duller, greyer lower scapulars and wing-coverts. Its back and mantle feathers may also be rufous-fringed and it may show quite noticeable narrow white mantle Vs. The more rufous appearance to the crown, mantle and scapulars is best appreciated when the bird is front-on. Like Semipalmated, the lower scapulars and greater coverts are greyer and they too show dark anchor-shaped marks behind the tip, but the bases of these feathers are slightly paler and the black marks are more pointed in shape – appearing as ‘arrowheads’ rather than ‘anchors’ – and they are less well defined. Like Little Stint, however, the plumage tends to fade somewhat late in autumn, prior to the post-juvenile moult. 3 HEAD PATTERN Like Semipalmated, it is has a uniform crown – although this tends to be fairly rufous – a whitish supercilium that curves up behind the eye, a well-defined ear-covert patch and a narrow white eye-ring, but it tends to differ in that the supercilium is often broader and the ear-covert patch paler and more diffuse. 4 UNDERPARTS Whiter than Semipalmated, no doubt because of the smaller, less well-defined area of more random streaking on the breast-sides. 5 MOULT A very useful short cut in their separation is the timing of their moult. Semipalmated migrates whilst still in juvenile plumage and most do not start to moult until they arrive on their wintering grounds (although the odd grey winter scapular or wing-covert can occasionally be seen by late autumn). Western, however, is like Dunlin in that it often – but not always – commences its post-juvenile moult whilst on migration (Grant & Jonsson 1984). This means that many autumn migrants show plain grey winter feathering (with a narrow black shaft-streak) mixed in with the rufous-fringed juvenile upper scapulars. This area of its plumage may also appear somewhat messy, as a consequence of it having already lost some of its juvenile feathering. 6 CALL Also reminiscent of Dunlin: a thin, shrill, high-pitched chreeep, treet or short jeet. Also a teet teet treep when flushed. 7 PALMATIONS Like Semipalmated, Western also has palmations between its toes.

Adult In marked contrast to Semipalmated, summer-plumaged Western is very distinctive and quite a striking bird. It is strongly rufous on the crown, ear-coverts, mantle and scapulars, while the breast is heavily streaked with black, with small black chevrons extending in a characteristic manner well down the flanks. In consequence, such birds are not particularly difficult to identify. Like adult Dunlin, its moult into winter plumage is often carried out whilst on autumn migration, so not only should July and August birds show evidence of upperparts moult but, more importantly, also the presence of plain grey winter feathering in the back and scapulars. First-summer It has been thought any ‘winter-plumaged’ Semipalmated/Western seen in Britain in summer is more likely to be a Western. This is because most such birds seen in North America are indeed Westerns. However, first-years of both species undergo a partial moult in spring, replacing variable numbers of first-winter head and body feathers. Some acquire nearly full breeding plumage and head north to their breeding grounds, whereas others remain on or near their winter quarters and either retain or moult into a winter-type plumage. About two-thirds of first-summer Semipalmateds remain behind (Chandler & Marchant 2001, O’Brien et al. 2006). Westerns winter further north than Semipalmateds and it may be that, in spring, some are prone to moving relatively short distances northwards into temperate latitudes, whereas non-breeding first-summer ‘Semi-ps’ do not. Although this may well be the case, it remains to be confirmed.

Where and when The E. Palearctic Red-necked Stint has occurred on just seven occasions (to 2010). All except one (a late August juvenile) have been worn adults from mid July to late September.

Structure Appears slightly shorter-legged than Little Stint with a shorter, stubbier bill (more like a short-billed Semipalmated Sandpiper). Also tends to look rather long-bodied and ‘horizontal’.

Plumage Summer adult In early spring, the fresh summer plumage is very grey, but broad grey feather fringes wear off to reveal a distinctive brick-red face and throat, fading to reddish-orange in late summer (when variable in extent but often strongest on the throat). Beneath the red is a variable but distinctive band of thick brown streaking, extending from the nape right around the upper breast. Brown across the lores, with a variable but subdued whitish supercilium (broadening behind the eye) and a narrow white eye-ring (like Semi palmated). The back and scapulars are a mixture of black, grey and white, as well as some brick-red, strongest in early summer, with variable white mantle Vs. Like Semipalmated, the primary projection is often short (but seemingly variable). Note that richly coloured summer-plumaged chestnut Sanderling C. alba have been confused with Red-necked Stint (Sanderling is much larger with a broad white wing-bar and lacks a hind toe in close views). Juvenile Superficially similar to juvenile Little Stint (but bill shorter) with head pattern more reminiscent of Semipalmated (lacks a split supercilium and has a dark ear-covert patch with a narrow white eye-ring enclosed within the grey). Overall, its plumage looks much greyer than juvenile Little Stint and this is most likely to draw attention to a vagrant: the head, breast patches and centres to the upperwing-coverts and tertials are distinctly pale grey (fringed white with a black shaft-streak). The back and scapulars, however, show contrasting bright orangey feather fringes, strongest and most consistent on the upper two rows of scapulars, but variable in extent and fading as autumn progresses. A weak white mantle V may be apparent, and white tips to many of the lower scapulars. The primary projection is longer than most adults, and is quite similar to juvenile Little Stint.

Call Quite distinctive: a soft, rolling, rather musical pleep or p-r-leep.

Where and when A very rare vagrant (36 records to 2011). Records fall into two categories: summer-plumaged adults in July/August and juveniles in September/October, with two spring (May) and one winter record.

Structure As its name suggests, it is the smallest stint, with a short, squat body and rather short legs; note that its toes are distinctly long and ‘spidery’. The bill is rather heavy based but tapers to a fine point. An important difference from Little Stint is that it shows only a very short primary projection, reaching just beyond the tertials.

Plumage and leg colour As a useful aide-mémoire, it may be helpful to think of Least as resembling a miniature Pectoral Sandpiper C. melanotos (even its calls are vaguely similar, albeit much higher-pitched). The key difference from Little Stint is leg colour: dull green or greenish-yellow (but beware of mud making the legs look dark). Juvenile Fresh plumaged individuals are richly coloured and suggest Little Stint in an initial view. Close views should reveal a distinct capped effect (may show a faint lateral crown-stripe) a dark line across the lores and a browner ear-covert patch (plus a narrow white eye-ring). The upperparts feathers are neatly fringed with rich buff, those of the scapulars being more richly fringed with chestnut (lower scapulars with white tips). It shows a slight mantle V, but this is narrower and weaker than on Little Stint. Most importantly, it has a complete breast-band of fine brown streaking (which may be weaker and narrower in the middle). Note that the background colour of the band is white, particularly in the middle, so the streaking may be surprisingly difficult to detect at a distance (when it may appear as side patches). Some individuals commence their post-juvenile moult by September, acquiring grey back and scapular feathers (with black shaft-streaks). Adult summer In many ways similar to juvenile, but early spring birds show greyish feather fringing that gradually wears off. Plumage then appears very dark above, with ill-defined whitish mantle and scapular Vs, the scapulars showing a mixture of white and chestnut feather fringes (wing-coverts browner). It too shows a distinct cap and a brown face patch. Returning autumn adults may appear very dark and worn. The breast-band and leg colour remain the key features. Winter Upperparts, head and breast-band brownish-grey, with thick black shaft-streaks to the upperparts and black streaking on the crown and breast, creating a more heavily patterned appearance than Little Stint.

Calls Readily separated from Little Stint: a soft, trilling treep, prreep, tr-rrr, or s-r-eep, longer when excited: s-s-s-s-sip.

Where and when A major rarity with just two accepted British records (1970 and 1982). The first was in June, the other a juvenile in August/September. There was another in Ireland in June 1996.

Structure In many ways the Asian equivalent of Least Sandpiper (it also has pale legs), but appears more upright, with longer legs and neck, producing a more ‘scrawny’ appearance. At a distance, its shape may suggest a miniature Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola, an impression heightened by its whitish supercilum, capped appearance and breast-band (see below). It can also look quite square-headed, flat-backed and pot-bellied, with a rather truncated rear end (like Least, it has little or no primary projection beyond the tertials). The legs appear about equal to the body depth, with a lot of tibia showing above the ‘knee’. Because of its long legs, it often ‘tilts forwards’ when feeding. The ‘jacana-like’ toes are strikingly long and well splayed. The bill appears relatively straight, being slightly less tapered than Least’s.

Plumage Juvenile A much more patterned and more richly coloured bird than juvenile Least. It has a dark cap, which is lined with chestnut (including a fairly obvious narrow ‘split supercilium’). The dark of the crown curves forward to connect with the lores, producing a ‘reversed J’ mark. It has a prominent whitish supercilium, a dark line across the lores, a narrow white eye-ring and a grey or brown fan-shaped ear-covert patch. At certain angles, the facial pattern can suggest juvenile Sharp-tailed Sandpiper C. acuminata or even a Dotterel Charadrius morinellus. The upperparts are well patterned with a prominent whitish mantle V, chestnut lines on the mantle and rich chestnut fringes to the upper scapulars and tertials. The lower scapulars and wing-coverts are duller, fringed with a mixture of pale buff and white. Like Least, it has a complete breast-band, but this is coarsely streaked (on a white background) and fades in the middle. The base of the bill is faintly horn or olive-coloured and the legs are bright lime-green. Adult summer Pattern similar to juvenile, including the ‘split supercilium’, the ‘reversed J’ mark on the face and complete breast-band. In fresh summer plumage it has prominent chestnut or orangey fringes to the upperparts, this rich coloration giving it a ‘foxy appearance’. However, plumage tones vary individually, with worn autumn individuals appearing much duller and browner. Winter Like Least, grey-brown above, strongly patterned with streaking on the head, neck and breast, and obvious dark centres to the upperparts feathers.

Calls Very similar to Curlew Sandpiper C. ferruginea, but much softer: a low and liquid chirrup or chree. Also, a more whistling upslurred poweep.

References Chandler & Marchant (2001), Cramp & Simmons (1983), Grant & Jonsson (1984), O’Brien et al. (2006).

Where and when White-rumped Sandpiper is an annual migrant that occurs in two distinct waves. Firstly, worn or transitional adults appear in July and August, almost exclusively on the east coast (one theory is that they arrive across the Arctic from Canada). The second wave relates to late autumn juveniles, mainly in west coast locations, from late September to early November. The species currently averages 19 records a year, with a peak of 39 in 2005. Baird’s is essentially a storm-driven vagrant, mainly juveniles in western areas from late August to October. It is extremely rare both in spring and late summer (and has wintered once). It currently averages seven records a year, with a peak of 12 in 2005. White-rumped is mainly a saltwater species whereas Baird’s tends to prefer freshwater habitats (often being found in grassy environments, such as airfields) although it too may be found with coastal waders.

General These two long-distance migrants are treated together as they are very similar in size and shape. Both are small, intermediate between Dunlin Calidris alpina and Little Stint C. minuta, and both are very long-winged, a result of their very long ‘scissor-like’ primaries. Three visible primaries extend well beyond the tail, producing a strikingly attenuated look to the rear end (primaries roughly equal in length to overlying tertials). When viewed front-on, Baird’s has a peculiarly broad, flat-backed appearance, almost as if it has been trodden on.

Plumage Summer adult In late summer, predominantly greyish, well streaked on the breast, extending down the flanks; chestnut is often present in any unmoulted summer scapulars. Many late summer adults, however, are already acquiring winter plumage on the back and scapulars, showing a mixture of plain grey feathers (with a black shaft-streak) and worn and messy white-fringed blackish or brownish summer feathers. The most obvious plumage feature is a well-defined whitish supercilium that tends to curve down and then up behind the eye. It also usually shows a fleshy or orangey base to the lower mandible, which Baird’s always lacks. If in doubt, wait until it flies; then, the key feature is the obvious, curved, white uppertail-covert patch, immediately in front of a plain, dark grey tail. Juvenile Also rather greyish on the head, neck and breast (the latter delicately streaked, forming a pectoral band), the head also showing a fairly prominent white supercilium. The upperparts are blackish, with all of the feathers neatly fringed white (but less scaly than Baird’s) and some rufous on the upper scapulars (and perhaps also on the crown and some wing feathers).

Call Markedly different from Baird’s: a quiet, unobtrusive, thin, mouse-like jit or j-jit, or a more rapid si-si-sit.

Plumage Summer Breeding plumage similar to juvenile (which see). Rather buff-coloured except that the upperparts patterning is more diffuse and less regular than juvenile. Late summer adults are likely to be worn and messy compared to pristine juveniles. Winter Breast and upperparts retain golden-buff tones but duller with less contrasting brownish feather fringes. Juvenile Neat and delicately patterned. Obviously buff-toned compared to White-rumped, but also relatively featureless. Rather plain-faced, the supercilium varying from buff and inconspicuous to whitish and fairly noticeable. At close range, it shows an obvious narrow whitish eye-ring. The most distinctive feature is a well-defined buff pectoral band that is profusely but delicately streaked with brown. The overall impression may therefore suggest a miniature, long-winged Pectoral Sandpiper C. melanotos, but it lacks that species’ white V’s on the mantle and scapulars. However, the upperparts are distinctive, being prominently scalloped whitish (strongest on the back and scapulars). Some have narrower, buffier and more subdued scalloping (and the scalloping is always less obvious at a distance). In flight, it lacks White-rumped’s white uppertail-coverts (dark instead). It also shows a variable wing-bar, often broad and obvious across the bases of the primaries but sometimes inconspicuous (narrow white tips to greater coverts). It may look long-winged in flight (although it can be surprisingly difficult to pick out from accompanying waders). Baird’s tends to be an active feeder, always on the move and often running at speed but, at other times, it may feed more furtively on flexed legs.

Call A thin, high-pitched kreep or prrrrt, vaguely recalling a thin, high-pitched Pectoral Sandpiper.

Confusion with Little Stint Baird’s may be confused with Little Stint, mainly because that species also has quite long primaries. However, juvenile Little Stints show stronger facial patterning, a noticeable white mantle V and the underpart streaking is usually confined to the breast-sides. Summer adults, however, may be buffier with a better-defined breast-band, but are more coarsely patterned. If in doubt, Little Stint’s primaries are usually only half to two-thirds the tertial length (or less). Little Stint’s call is also different: a quiet, unobtrusive tip or tip tip tip.

Where and when Dunlin is our commonest small shorebird, often abundant on estuaries in winter and large numbers of migrants pass through in spring and autumn, when it may also be numerous inland (usually when water levels are low). Small numbers breed in upland areas, mainly in n. England and Scotland. Curlew Sandpiper is a migrant from Siberia. Adults pass through mainly in eastern areas in late spring and early autumn, and larger but variable numbers of juveniles are more widespread from August to October; very rare in winter. Broad-billed Sandpiper is a very rare migrant, mainly in spring (May/June) and very occasionally in autumn (July to September) mainly to English east coast (averages about four a year). Canadian and Greenland-breeding Knot winter on selected estuaries, principally in NW England and the Wash, where they may occur in huge concentrations; more widespread on migration when small numbers turn up inland, mostly juveniles in August/September.

General features This abundant small wader should act as the yardstick when identifying all similar species. A small, hunched, rather dumpy bird with a medium to long, gently decurved bill. Bill length varies: the migrant races schinzii (SE Greenland, Iceland, Britain and s. Scandinavia) and the much rarer arctica (NE Greenland) – both of which winter mainly in w. and NW Africa – have shorter bills than alpina (n. Scandinavia and NW Russia) which is common in winter. They feed in large flocks on mudflats, not bunching as tightly as Knot, picking and probing with the bill held downwards.

Flight identification Forms tight flocks like Starlings Sturnus vulgaris, flashing grey and white as they twist and turn over the mudflats. Closer views reveal a rather plain pattern, with a narrow white wing-bar and a dark line down the centre of the rump.

Call A distinctive, drawn-out, slightly rasping treeeeep.

Song Similar in quality to the call: a fast, dry and almost rasping treee-treee-treee…, develop ing into a drawn-out rapid, pulsating, almost buzzing tree-ee-ee-ee-ee-ee-ee….

Plumage Three distinct plumages. Adult summer Easily identified by the strong buff or chestnut-patterned upperparts and large black belly patch; upperparts wear darker by late summer. Continental alpina averages more chestnut than the buffier schinzii and arctica. Winter Rather nondescript, with a grey head and upperparts and a strong grey suffusion to the breast-sides (and light streaking across the centre); slight supercilium. Juvenile Rather like a dull version of adult summer. The upperparts feathering is broadly edged chestnut and buff, and the buffish breast is lightly streaked brown. Most importantly, the belly is noticeably streaked blackish, usually forming a messy patch that mirrors the black belly patch of breeding adult. Juveniles generally look neat compared to contemporary summer adults, which often look patchy and scruffy when moulting into winter plumage. Note that, unlike most small waders, juvenile Dunlins commence their moult into winter plumage in late summer, so many start to show grey patches on the scapulars whilst on migration, these increasing in area as autumn progresses.

General features Slightly larger, taller, ‘leggier’ and more elegant than Dunlin; some larger individuals can be very obviously taller (females average larger than males). Legs and bill longer, but differences in bill length and curvature subtle and should not be too heavily relied upon for identification. Juvenile has a longer primary projection than most Dunlin (less apparent on adults). Often feeds in deep water, immersing the bill and head below the surface (Dunlin also feeds like this, but less persistently).

Flight identification Easily separated from Dunlin by its striking white rump, contrasting with the grey tail.

Call Flight calls similar in quality to Dunlin, but slightly softer and markedly disyllabic: a soft, rolling shirr-up, very distinctive once learnt.

Plumage Adult summer Easily identified by reddish underparts. Size and structural differences separate it from summer Knot. Fresh summer plumage has white tips to the red feathers, so spring birds may show a strong grey cast (strongest on females) which gradually wears off as summer progresses. Winter Full winter plumage is uncommon in this country, as most spring and autumn adults show traces of summer plumage (noticeable red blotching on underparts in autumn). Winter plumage is very similar to Dunlin, Curlew Sandpipers being surprisingly difficult to pick out at any distance; the most obvious differences are a slightly stronger, thin white supercilium, extending well behind eye, and a slightly whiter breast (although this is variable on Dunlin). Perhaps best located by the subtle structural differences outlined above. Juvenile From mid August onwards, the vast majority of migrants are juveniles. For separation from Dunlin, concentrate on the underparts. Juvenile Curlew Sandpiper always looks neat and immaculate, with smooth, clean, white underparts with a noticeable soft peachy tint to the breast (gradually fades as autumn progresses). Any streaking on the breast is fine and inconspicuous. This is in marked contrast to accompanying juvenile Dunlins, which show noticeable blackish belly streaking, markings never shown by juvenile Curlew Sandpipers. Whereas juvenile Dunlin has thick and coarse upperparts patterning (often with patches of grey first-winter feathering on the scapulars), the upperparts of Curlew Sandpiper are finely and neatly scalloped, the rather washed-out pale greyish-brown feathers having a narrow black subterminal line and narrow buff fringes. It also has a better-defined supercilium than Dunlin and often a slight capped appearance. Perhaps more likely to be confused with winter adult Dunlin, but the latter is uniformly pale grey above, with grey shading on the breast-sides.

General features Structurally similar to Dunlin, but noticeably smaller and slightly shorter-legged. Noticeably thicker bill and the tip often looks distinctly down-kinked. Despite statements to contrary, not particularly lethargic.

Flight identification Summer adults and juveniles look very dark and blackish, and show an obvious breast-band and a narrow white wing-bar.

Call A distinctive dry, hard trilling pprrrrrrk.

Plumage Adult summer Most of those occurring here are summer-plumaged adults, which are easily identified. At a distance, they look very dark – blackish – with a dark, buffy-brown breast-band and messy dark mottling on the flanks. At closer range, the upperparts feathers are neatly fringed whitish, very obvious when fresh; two sets of mantle and scapular lines recall Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago. Also, there is some chestnut fringing, especially on the upper scapulars. Most distinctive is the striped head pattern, which strongly recalls that of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus: a thick white supercilium forks before the eye, producing a very distinctive ‘split supercilium’. The prominence of this is highlighted by the very dark crown and dark eye-stripe, which broadens into a thick patch on the ear-coverts. (Note that the ‘upper supercilium’ but may be difficult to detect on distant worn birds in late summer.) Some fresh spring migrants show frosty grey feathering about the head and breast (that gradually wears off). Late summer and autumn adults lose much of the pale upperparts fringing through wear and can appear rather uniformly blackish above. Winter Full winter plumage is unlikely to be seen in this country. The predominantly blackish summer feathering is replaced with grey, but the characteristic head pattern is retained (although the split supercilium is subdued and not obvious). Darker leading lesser coverts form a dark patch at the bend of the wing. Winter adults can be surprisingly difficult to pick out from Dunlin. Juvenile Very dark like summer adult, but fresh and immaculate at a time when adults are scruffy and worn. The breast-sides are finely and evenly streaked, and the upperparts show well-defined white feather fringes and mantle and scapular stripes. When very fresh, they may show a faint buff wash on the breast.

General features A rather bland-looking bird that inexperienced observers may struggle to identify. At rest, best identified by size and structure: a rather bulky, medium-sized wader (much larger than Dunlin) with a short neck and long body. Note in particular that the bill is relatively short, as are the legs (greenish or greyish, not black). Unlike Dunlin, it has an attenuated rear end with long primaries that project well beyond the tertials (exposed primary length is approximately equal to tertial length). A rather slow, methodical feeder. At its main wintering sites it forms huge, tightly packed flocks that carpet the ground when roosting.

Flight identification Easily distinguished by the combination of obvious thick white wing-bar and pale, greyish-white rump and tail (rump and uppertail-coverts finely barred grey and white at close range).

Call An unremarkable unobtrusive, soft, quiet oo-ik or oo-ik-ik, unlikely to attract attention.

Plumage Adult summer Easily identified by brick-red underparts (females tend to be paler than males and both sexes may fade by late summer). Moulting adults are patchy. Structure and bill length easily separate it from Curlew Sandpiper. Winter A very pale grey bird, plain above (with faint pale feather fringes) and a lightly mottled grey breast; grey chevrons extend onto the flanks. Lacks a strong facial pattern (weak whitish supercilium). Juvenile Similar to winter, but upperparts feathers neatly and finely scalloped, each feather having a narrow dark subterminal line and a narrow whitish fringe. The breast and flanks are finely streaked but the belly has a distinctive soft peachy tint, which gradually fades as autumn progresses. A noticeable white supercilium curves down and then up behind the eye. Plumage usually looks smooth and immaculate.

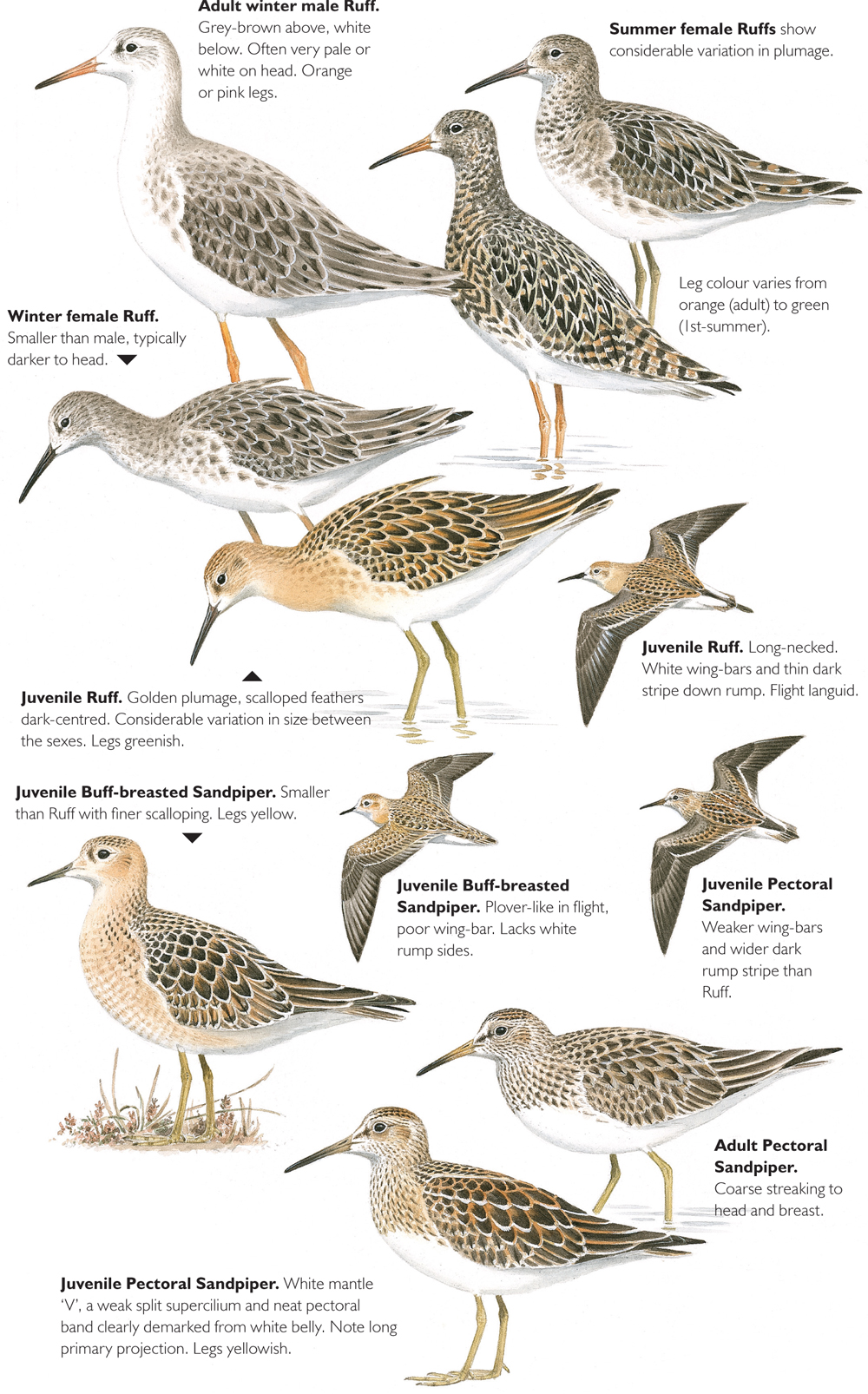

Where and when Ruff is a very rare and erratic breeding bird but is far more numerous as a migrant, mainly in freshwater habitats; variable numbers winter, mostly in s. Britain, tending to occur in fields with Lapwings Vanellus vanellus and Golden Plovers Pluvialis apricaria. Buff-breasted Sandpiper is a North American visitor, mainly to w. Britain and Ireland in September (records in spring and late summer, often on the English east coast, may relate to birds that arrived in previous years). Numbers vary, but it currently averages 25 a year; small parties sometimes occur (a remarkable arrival occurred in 2011, with provisional estimates of 75 in Britain and 90 in Ireland, including a flock of 28 at Tacumshin, Co. Wexford). Pectoral Sandpiper is another North American species, currently averaging 110 records a year, with a peak of 192 in 2003. Most occur in September/October with records in spring and late summer, often in e. England, thought to relate to birds that crossed the Atlantic in previous years or possibly to individuals from e. Siberia, where it also breeds. It has very rarely wintered. A pair almost certainly bred in Scotland in 2004.

General features Apart from the male’s remarkable display plumage, in many ways a rather nondescript wader, variable in plumage, bare-parts colour and size; consequently, it is often confusing to inexperienced birders. Males and females differ markedly in size, males being about the size of Common Redshank Tringa totanus, females (also known as Reeves) c. 25% smaller. Rather a gangly looking bird: short-billed, small-headed, long-necked and bulky bodied (sometimes looking humpbacked) and often showing a bulging ‘Adam’s apple’ at the front of the neck. It strides around in a purposeful manner, picking at the mud, but will also wade, immersing both its bill and its head below the surface. Distant individuals can be confused with Redshank, which has a similar walk, but the latter has a longer, straighter bill and darker, more uniform plumage. Adult Redshank has red legs, but late summer juvenile’s are orange, a colour also shown by adult Ruffs. If in doubt, wait until the bird flies: Redshank’s white secondaries and rump should be obvious.

Plumage Four basic plumage types occur. Juvenile Most August to October migrants are juveniles, which are easily separated from adults. The underparts are a distinctive orangey-buff (white on the rear belly and ventral area). The upperparts are neatly patterned with buff feather fringes that produce a distinctive scalloped appearance. The bill is dark and the legs dull grey-green. Juvenile plumage is gradually lost in late autumn/early winter body moult. Winter Acquired by adults from late summer onwards, by juveniles from late autumn onwards. More distinctive, being essentially pale grey above (with noticeable pale grey or whitish feather fringes) and white below (with subdued grey mottling on the breast-sides and flanks). It has a white eye-ring and many show a noticeable white patch at the base of the bill (generally strongest on adult males). Some, nearly always males, have variable patches of white on the nape, sides of the neck and/or breast, and some are completely white-headed and very striking. The bill usually has a pink or orange base (especially males) and the legs are bright pink or orange; first-winters, however, retain a black bill and dull, greenish legs. Adult summer Males readily identified by their remarkable ornamental head plumes, which vary from white, black and white, through black and brown to ginger; some plumes are heavily barred. This plumage is, however, rarely seen away from the Continental breeding grounds, although passage males often show obvious traces of it, as well as variable black markings on the upperparts. Confusingly, some breeding males are female-like. Adult females are also variable: essentially brown, variably and irregularly patterned with coarse black markings above, and more delicately patterned on the head and breast. The bill is dark, often with a pink base, while the legs vary from pinky-orange to green (the latter no doubt mainly first-summers).

Flight identification A noticeable whitish wing-bar becomes broader and more diffuse across the bases of the primaries; distinctive white V-shaped patches on the lateral uppertail-coverts (some virtually lack the dark central dividing bar, creating a white crescent-shaped ‘rump patch’). Long-winged, with an easy, languid flight action.

Voice Oddly silent, but rarely gives a low, hoarse grunt.

Size and shape Superficially similar to a small juvenile female Ruff, but easily identified. Male slightly larger than female but, whereas Ruff is a medium-sized wader, Buff-breast is basically a small wader, only slightly taller than a Dunlin C. alpina. Although its shape resembles Ruff, it is less gangly, being more horizontal, proportionately longer-bodied and squarer- headed. Unlike Ruff, juveniles show two or three long primaries projecting noticeably beyond the tertials, producing an attenuated rear end (although adults have longer tertials).

Plumage Juvenile The entire underparts are uniformly pale buff, paler and less orange than juvenile Ruff. The vast majority of September/October vagrants are juveniles, which appear immaculate; a few of these may be much whiter on the belly and a small minority show abrupt demarcation between the buff and the white. They also show delicate black spotting on the breast-sides. A large dark eye and pale eye-ring stand out on the bland, plain-looking face, while the streaked crown can give a slight capped effect. Like Ruff, the upperparts feathers are fringed buff, but the edgings are narrower so the upperparts appear much less coarsely patterned. Legs pale yellow (greenish on juvenile Ruff). Summer adult Broader, less well-defined buff fringes to the upperparts feathers, lacking juvenile’s dark sub-terminal crescents. Autumn adults may begin to show varying amounts of winter upperparts feathering, which has broad buff fringes.

Habitat and behaviour Frequents short-grass habitats, such as golf courses and airfields, but will also associate with other small waders in more typical freshwater environments. An active feeder, walking quickly and daintily on slightly flexed legs, picking every two or three steps, but actions rather erratic, with frequent changes of direction (it lacks Ruff’s smoother, more confident walk and slower, more deliberate picking action). Constantly bobs its head whilst walking. Unlike Ruff, does not wade into water to feed. Often very tame, sometimes crouching low and freezing when approached.

Flight identification Always looks small and rather plover-like, lacking Ruff’s easy, languid flight action. The upperparts pattern is completely different from Ruff: it lacks a prominent wing-stripe and prominent white patches on the sides of uppertail-coverts. Instead, it shows a faint and diffuse pale bar across the base of the upper primaries, and the rump and uppertail-coverts are plain. The underwings are dull silvery-white, with a thick dark crescent across the under-primary coverts. Unlike Ruff, the feet do not project beyond the tail, so it lacks an attenuated rear end. It may suggest a miniature Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria in flight.

Voice Like Ruff, strangely silent, but occasionally utters an insignificant, quiet, soft, downward cheu.

Size and shape A medium-sized wader with a mid-length, slightly decurved bill and medium-length legs. Although superficially similar to Ruff, it is smaller, shorter-legged and quite different in shape: less upright and more horizontal with a rather long, pear-shaped body and an attenuated rear end. It has a very long primary projection, the exposed primaries being about equal in length to the overlying tertials (the tertials virtually cover the primaries on Ruff). Perhaps 10–15% larger than Dunlin although, like Ruff, size varies sexually, some small females being much closer in size to Dunlin.