Where and when Arctic Skua breeds in n. and w. Scotland but is a widespread coastal migrant, mainly in April/May and August to October (with a few lingering into winter). Pomarine Skua is an uncommon migrant, mainly in late April/May and August to November but, unlike the other two species, small numbers regularly occur throughout the winter, particularly in the North Sea. Most are seen on spring passage, when variable numbers move up the English Channel and also north through the Irish Sea. The vast majority, however, move up the Atlantic and, during strong north-westerly winds, large numbers may be seen off the Outer Hebrides and nw. Ireland. Long-tailed is by far the rarest skua (about 370 records a year in 1981–90) but breeding has been attempted. Like Pomarine, the vast majority move up the Atlantic, and north-westerly winds may also produce a large spring passage off the Outer Hebrides. Otherwise, small numbers are most likely to be encountered in August/September, mainly off North Sea coasts (it is very rare in the English Channel). A huge autumn movement in 1991 produced a British record for that year of 5,350, mainly in the North Sea (Fraser & Ryan 1994). All three species can appear inland; in fact some routinely migrate overland, appearing on fresh water and even in fields (the latter mostly Long-tailed) particularly during gloomy anticyclonic weather. Such birds may be incredibly tame.

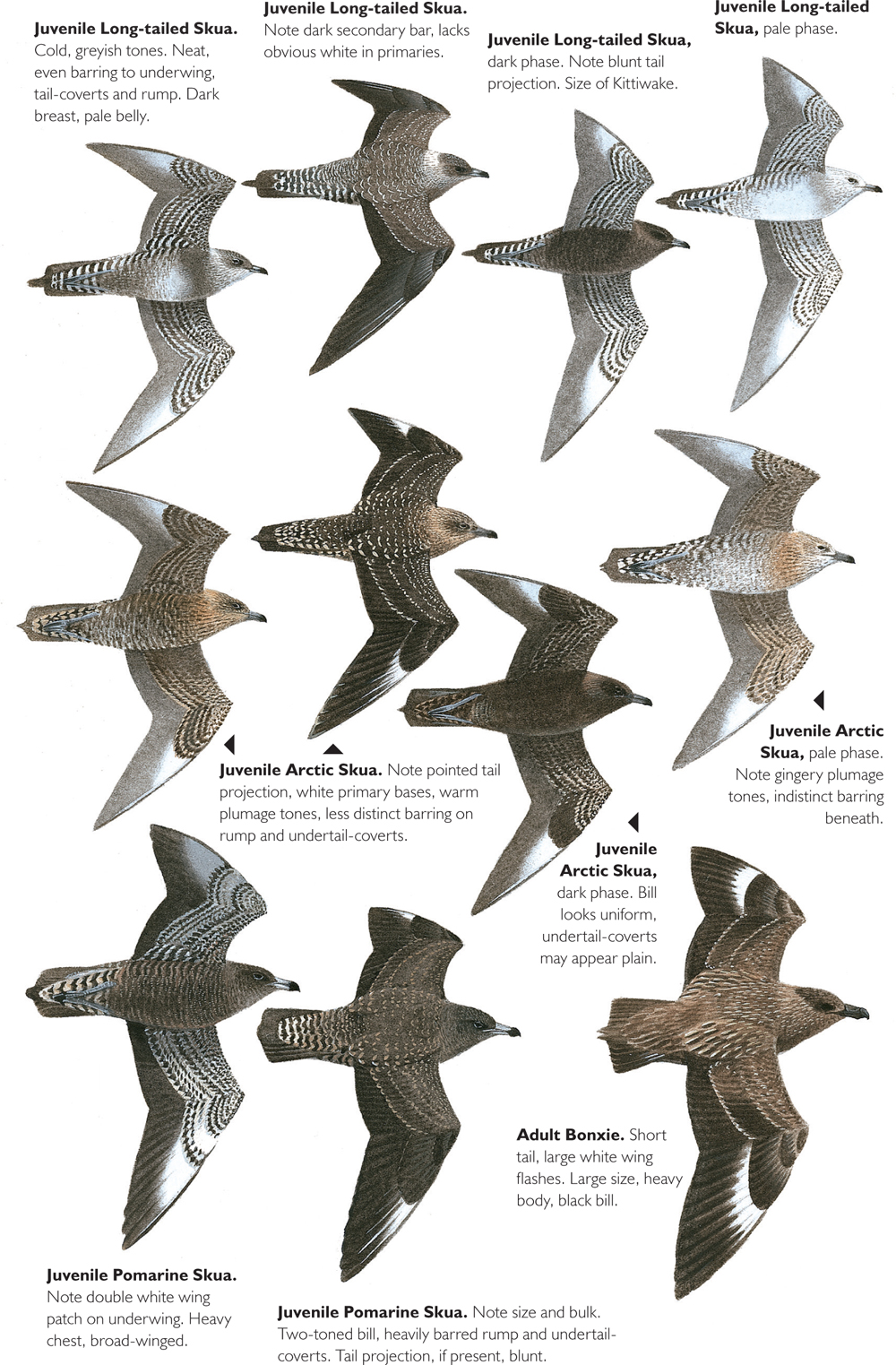

General approach Skuas are exciting birds that always enliven a sea watch but, with the exception of adults in summer plumage, the three smaller species are notoriously difficult to identify. Any discussion of their identification is complicated by their variability. Firstly, adult Arctics and Pomarines have pale and dark plumage morphs (as well as intermediates). Secondly, juvenile plumages of all three species are similar, and individual variation at this age is considerable. Thirdly, skuas do not reach maturity until about three to five years old. As they usually remain in their winter quarters during their first summer, their immature plumages are unfamiliar to Northern Hemisphere birders. The identification of immatures can also be complicated by bleaching and wear. Fourthly, judging their size is complicated by the fact that females are significantly larger than males (averaging c. 12–15% heavier). Although experienced seawatchers may confidently identify skuas at some distance (largely by ‘jizz’) less-experienced birders should exercise caution and identify only those that are seen well; be prepared to log some as ‘skua sp.’. It is an odd paradox that distant skuas at sea are routinely identified with confidence, even by inexperienced birders, yet close-range birds inland often prove controversial. In view of the complexities of identifying winter adults and immatures, only summer adults and juveniles are dealt with in depth; other plumages are outlined on p. 196. Finally, note that adults retain their summer tail projections throughout the autumn until they moult in their winter quarters, but the projections may be susceptible to loss or damage.

Structure Generally the commonest small skua, this species should act as the yardstick when identifying the other two species. Size intermediate between Pomarine and Long-tailed, being similar to Common Gull Larus canus, but much sturdier. Structural differences from Pomarine and Long-tailed are dealt with under those species but, compared to Pomarine, note Arctic’s medium build, being smaller and slimmer with a longer-looking head, narrower wings and tapered rear end; adults have an obviously pointed tail projection, which may be as long as 10.5cm (4.5 inches) suggesting Long-tailed. Conversely, skuas of all species and ages can occasionally lack central tail feathers, either through moult or damage. At close range, the bill is rather slim and slender, lacking Pomarine’s more obvious gonydeal angle.

Flight Migrating flight is steady, but less heavy and ponderous than Pomarine. All three species glide on distinctly arched wings. In strong winds, Arctic may adopt a shearwater-like flight, rising and falling above the waves in a series of long arcs, but the wings are held more arched than most shearwaters and the arcs tend to be flatter.

Plumage Adult summer Dark-phase adults are commonest and they appear completely dark fulvous-brown; a yellowish shade to the cheeks and ear-coverts is not obvious at any distance. Pale-phase adults have a blackish cap and are mainly white below, usually with a pale yellow face; they often have a brown breast-band of variable width and extent, but generally weaker than Pomarine. At close range, three or four white shafts on the upperwing, at the base of the primaries, are noticeable ( cf. two on Long-tailed) and these show as a pale crescent on the underwing. The upperparts are brown; pale and intermediate birds are warmer-toned than Pomarine or Long-tailed and the upperwing-coverts show little or no contrast with the black secondaries ( cf. Long-tailed, which shows marked contrast). Intermediate adults vary between dark and light phases. Juvenile Except for some very dark birds, juvenile skuas can usually be aged by their barred underwing-coverts and axillaries, blue-grey to pinkish-grey bill base and blue-grey to whitish legs. Plumage tone varies, Arctic and Long-tailed being more variable than Pomarine. The underparts of Arctic vary from uniformly blackish through brown to greyish-white, narrowly barred brownish. Differences from Pomarine and Long-tailed are outlined under those species, but the following are the main characteristics of Arctic. 1 DARK PHASE Note that very dark juvenile Arctics are solidly blackish-brown throughout, lacking any obvious barring (but a few dark Long-taileds can look similar, especially at a distance). 2 FEATHER FRINGES The pale feather fringes on pale and intermediate phases are warm in tone (rufous or buff) and do not contrast with the richer brown background plumage; this renders their entire plumage warmer-toned than Pomarine or Long-tailed (thus appearing ‘foxy-toned’: yellow-brown or rufous-brown). 3 HINDNECK Unlike Pomarine, most have a contrastingly pale hindneck, which is often warm-toned. 4 UPPER- AND UNDERTAIL-COVERTS Although often thickly barred brown and buff, the barring is not especially contrasting so, unlike Pomarine and Long-tailed, they fail to show obviously paler upper- or undertail-coverts. 5 UPPER-PRIMARY PATCH The shafts on the bases of the first three or four primaries are white (only two are white on Long-tailed). 6 UNDER-PRIMARY PATCH There is a single white flash on the under-primaries so, unlike Pomarine, it does not generally show a narrow pale crescent in front of the large pale patch. 7 PRIMARIES At rest it shows noticeable pale tips to the primaries (not shown by Pomarine or Long-tailed). 8 TAIL PROJECTIONS Short and pointed (always blunt on Pomarine; blunt and usually longer on Long-tailed). 9 BILL Usually rather uniformly dark, lacking an obviously paler base.

Structure Summer-plumaged adults are most easily identified by their blunt, twisted central tail feathers, which look like spoons or legs/feet trailing out behind. These are retained throughout the autumn until their winter moult. However, the ‘spoons’ may be abraded or even broken off by late autumn and even in spring a minority show only slight protuberances. Juveniles lack ‘spoons’ but they have a short, blunt projection (pointed on Arctic); this is quite noticeable in closer views (down to c. 400m) but difficult to see at any distance (and may even be absent). In winter plumage, adults show a short projection that is hardly twisted. With Pomarines lacking ‘spoons’, it is essential to concentrate on overall size and structure. Although size evaluation may be difficult with lone birds, Pomarine is a large skua, approaching Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus (about four-fifths the size in direct comparison) or c. 10% larger than Common Gull (Arctic is more similar in size to the latter). It is a sturdy, thickset, powerful and ‘meaty’ bird with a large head, a chunky body and a shorter-looking rear end; note also the heavy, hooked bill. Most importantly, the wings are broad-based and it has a sturdy, robust appearance in flight (in direct comparison, Arctic Skua is smaller, noticeably slimmer and flatter-chested); on summer adults, the deep-chested appearance may be emphasised by a thick dark breast-band. They may also show a more ragged appearance to the vent. Juveniles or dark-phase adults can be confused with Bonxie S. skua, a mistake unlikely with Arctic. On the ground, they again look big and bulky with a relatively short primary projection.

Flight Even in direct comparison there may little difference in their flight action. However, Pomarine generally has a slightly slower, steadier, more ponderous and more lumbering flight than Arctic, with continuous gull-like flapping low over the waves – often ‘hugging’ the sea – interspersed with short glides on bowed wings. Thus, the flight is not as ‘fast and dashing’ as Arctic. Like that species, it shears in long arcs during strong winds. When pursuing prey, the wingbeats are deep and bowed. Unlike the smaller skuas, it habitually kills and eats quite large birds, such as smaller gulls. It also chases larger birds for food, such as Herring L. argentatus and Lesser Black-backed Gulls, and may even force them into the sea. Like Bonxie, it often feeds on scraps.

Plumage Adult summer Approximately 90% of adults are pale phase. Apart from the tail ‘spoons’ no single character separates Pomarine from Arctic, but ‘Pom’ is generally darker, blacker-brown above, and usually has a prominent dark breast-band (but some, mainly males, just show patches on the breast-sides). It also has larger whitish wing patches as well as a greater incidence of flank barring (but beware of the superficial similarity between adult Pomarine and subadult Arctic). The extensive white face (extending onto the nape) is usually obvious at all ranges, and this is usually (but not always) washed pale yellow, visible at some distance. Dark-phase birds are completely dark brown and very striking, but their whitish wing flashes may appear less obvious than on pale birds. Many ‘Poms’ retain traces of winter plumage well into summer and such intermediate individuals appear much duskier below, especially at a distance. Juvenile The main differences from Arctic are as follows. 1 PLUMAGE TONE Pomarine is fairly consistent in plumage tone, being generally rather dark brown, with no warmth to its plumage. The body plumage is variably barred buff (strongest on pale-phase individuals) and the barring is better defined than on Arctic. 2 UNDERWING CRESCENT One of the best plumage features is a whitish crescent in front of the large and very obvious silvery-white patch at the base of the under-primaries; the crescent is formed by pale bases to the greater under-primary coverts and, in good light, is visible at long range. Arctic may show a faint, diffuse crescent in front of the under-primary patch, but this is hardly visible in the field. The white flash on the upperwing is less obvious. 3 TAIL-COVERT BARRING Strong brown-and-whitish barring on the uppertail-coverts forms a noticeable pale ‘rump’ in flight; the undertail-coverts, vent, lower belly and, sometimes, the flanks, are similarly barred. The equivalent barring is less contrasting and less obvious on Arctic, and note that dark Arctics usually lack barring altogether. 4 BILL Longer and heavier than Arctic, with a more prominent gonydeal angle. The basal two-thirds are pale bluish, olive or sandy, contrasting with the dark tip (recalling juvenile Glaucous Gull Larus hyperboreus); the pale base may ‘flash’ paler at a distance. Arctic’s bill base is less prominent because (a) it is usually slightly darker, (b) the bill is smaller and (c) the adjacent head feathers are paler and do not contrast with the base. 5 HEAD Drab grey-brown, rarely showing Arctic’s contrastingly pale hindneck (but may show a paler grey wash). Thus, wholly brown-headed birds with barred underparts are almost certainly Pomarine. The few Arctics that lack a contrasting light hindneck are usually solidly blackish-brown, with unbarred underparts. Dark streaking on the head is typical of Arctic and is never present on Pomarine, which instead is lightly barred. 6 TAIL PROJECTIONS Short and rounded (always short and pointed on Arctic); some Pomarines lack projections altogether. 7 LEG COLOUR There is overlap in leg colour: bluish-grey, and all three species may show whitish legs. Second-winter See ‘Appendix’ p. 196.

Structure Although there is size overlap, Long-tailed is as different from Arctic as Arctic is from Pomarine. A small skua, similar in size to Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus. Adults are readily identified by their incredibly long central tail feathers which waver in flight. They can have streamers up to 18cm (7 inches) in length but note the overlap with Arctic, which can have projections up to 14cm (5.5 inches). However, Arctic’s tail tends to appear thick and tapered, whereas Long-tailed’s projections are obviously long and thin (the two separate feathers are often clearly visible). Juvenile Long-tailed has a short to medium blunt tail projection (see below). Unlike the other skuas, it has no bulk to its body, being slimmer with a shallower breast; on the water, it appears slim and elongated. It has a smaller bill than Arctic, with less of a gonydeal angle, and a smaller, more rounded head. This combines to produce a much gentler character and appearance, perhaps recalling Common Gull.

Flight Narrower wings than Arctic, especially at the base, and often appears light, slim and agile, the whole effect being more tern-like. It tends to have a more continuously flapping flight, with little gliding, and may even feed with small gulls, dropping down to the water’s surface to pick up food. Inland birds may pick insects off the water or even hawk them in the air; others have fed on earthworms in ploughed fields.

Plumage Adult summer Do not rely solely on tail length, but concentrate on structure and plumage. Long-tailed is more consistent in its appearance than Arctic and even Pomarine: dark-phase birds are very rare and intermediates virtually unknown. Typical adults differ from Arctic in the following respects. 1 CAP Neat, clear-cut and black, contrasting sharply and smartly with the white face (often washed pale primrose-yellow). 2 UNDERPARTS White, lacking a breast-band, but lower belly and vent obviously dark (ashy-grey, like upperparts) merging but contrasting with the obvious white upper breast and face (sometimes the dark belly extends up to the lower breast). Therefore, the front end looks white, the rear end dark. However, some are much whiter-bellied (mainly from Greenland, North America and E. Siberian populations, race pallescens). 3 UPPERPARTS Cold ashy-grey, not as dark as Arctic. The primaries and secondaries are black, the latter contrasting with the wing-coverts to form a noticeable dark trailing edge to the wing (Arctic appears plain brown above). The tail is black, contrasting with the paler rump and uppertail-coverts. 4 upper-primary patches Significantly, there is little or no white in the upperwing: usually just two white primary shafts (Arctic has white bases to three or four, forming a definite patch). 5 UNDERWINGS Dark silvery-grey with a contrasting black border to the front and rear of the wing; as on the upperwing, just two pale shaft-streaks on the outer primaries. Juvenile Exhibits a variety of plumage tones, from pale through intermediate to dark. Paler individuals can be separated from Arctic by the following differences. 1 PLUMAGE TONE Generally colder and greyer-looking than Arctic. 2 UPPERPART BARRING Upperparts show clearly defined cream or whitish barring, contrasting with the grey-brown background colour, producing a neat, scaly effect at a distance (Arctic has darker, buffier barring that contrasts less with the browner plumage, producing a warmer tone to the upperparts). 3 UPPERTAIL-COVERTS In flight, heavy brown and whitish barring produces a noticeable whitish ‘rump’ (duller and less obvious on Arctic, some having plain upper- and undertail-coverts, never found on Long-tailed). 4 TAIL PROJECTIONS Blunt-tipped; length varies from short to medium. Always short and pointed on Arctic, so those Long-tailed that show longer projections are quite distinctive, although the projection can be difficult to make out at a distance. Beware of Arctic Skuas that lack central tail feathers, the two adjacent ones then appear to be blunt central feathers. 5 PRIMARY PATCHES Only one or two white primary shafts (although white on the bases of the third and fourth may be perceptible at point-blank range). On Arctic, three or four show obvious white. Consequently, Long-tailed shows little white on the upperwing, but has a larger broad pale whitish-grey crescent-shaped patch on underwing. 6 UNDERPARTS Typically greyish, with finely barred flanks; many show a darker head and neck, with a large whitish area immediately below. Undertail-coverts strongly barred. 7 HEAD A pale greyish area on the sides of the head and nape shows to a greater or lesser degree. Some pale individuals are strikingly white-headed. 8 UNDERWING-COVERTS Heavily barred, especially on the axillaries (some darker Arctics have uniform underwing-coverts, never found on Long-tailed). 9 BILL Generally more black at tip (40–50% of bill is black, compared with 25–30% on Arctic) and the black usually extends back past the gonydeal angle and frequently tapers along the cutting edge, about halfway into grey base. 10 PRIMARIES Unlike Arctic, it lacks buff fringes to the tips of the closed primaries, which appear plain black at rest. Dark juveniles Much more similar to dark Arctic but they show more contrastingly pale buff feather fringes to the upperparts (although some are very finely patterned and look wholly dark at a distance). However, on closer birds, quite striking dark brown-and-white barring on the undertail-coverts should be obvious, both at rest and in flight.

Owing to the complexities of identifying winter adults and immatures, it must be stressed that the following details are generalised. Adult winter On failed breeders, winter plumage starts to appear from July onwards and may be complete by August, but for most the moult starts from late August and is completed in the winter quarters. Unlike most juveniles, winter adults lack underwing-covert and axillary barring, and have a black bill and legs. On pale-phase birds, the cap becomes less distinct and the throat and neck duskier. The upperparts feathers show pale fringes and the tail-coverts are barred, as on juveniles. Dark-phase individuals are more similar to summer adults, but may acquire indistinct barring on the tail-coverts. All adults have shorter tail projections in winter, while moulting individuals may temporarily lose them altogether. Immatures Owing to our incomplete knowledge, the following gives only an outline and it should be stressed that immature skuas are notoriously variable, a problem exacerbated by wear and bleaching. The following details relate to Arctic Skua (from BWP), but the sequence appears similar for all species, although Pomarine appears to take a year longer to reach maturity. Juvenile plumage is moulted in midwinter and ‘first-winter’ plumage is characterised by a mixture of adult winter (including slightly longer tail projection) and juvenile characters (such as pale legs and, on pale-phase birds, barred underwing-coverts and axillaries). Dark-phase ‘first-winters’ are more similar to juveniles, but on average less heavily barred. ‘First-winter’ plumage is retained until late summer, when it is replaced directly by second-winter, so there is no first-summer plumage. In their second summer, some skuas arrive at the breeding colonies with variable amounts of adult-like summer plumage mixed with second-winter plumage. From then on, the moults gradually produce a more adult-like plumage until maturity, and traces of winter plumage are no longer retained in summer. However, some fully mature adults (mainly Pomarines) retain traces of winter plumage on arrival on the breeding grounds. Some mature earlier, so ageing is very difficult once juvenile characters are lost (such as the pale legs and partially barred underwing-coverts and axillaries).

Appendix Second-winter Pomarine Skua Given Pomarine’s propensity to winter around our coasts, the following details may be useful, based on a well-studied November individual. Uniformly dark brown upperparts, head and breast, the latter producing a hooded effect in flight (with a slight dark cap). Belly silvery-white but flanks and undertail-coverts heavily barred pale buff. Pale tips to the uppertail-coverts formed a noticeable pale ‘rump’ in flight. Noticeable blunt tail projection. Underwing-coverts plain brown (barred on juvenile) and legs and feet largely blackish (obviously pale bluish-grey on juvenile, sometimes whitish). Plumage less immaculate than juvenile, with clear signs of inner primary moult. The narrow whitish crescent in front of the large whitish under-primary flash was faint. Bill appeared ‘blob-ended’, the black tip contrasting with a slightly paler base.

References Broome (1987), Davenport (1987), Fraser & Ryan (1994), Jonsson (1984), Mather (1981), Olsen & Christensen (1984), Stoddart (2012), Ullman (1984).

Where and when Kittiwake is a common coastal species throughout the year, but rarer in winter; it also migrates overland and small numbers (occasionally large flocks) may appear on inland lakes and reservoirs, mainly in March/April and September/October. Little Gull is a scarce passage migrant, mainly from March to May and August to October, but smaller numbers are encountered throughout the year; it is much more likely to be seen inland than Kittiwake. Large numbers occur at selected coastal sites, notably in the North Sea, with over 6,000 sometimes gathering off the Yorkshire coast. Sabine’s Gull is a rare autumn passage migrant from Canada, mainly in September/October, with occasional spring occurrences from March to June; it is extremely rare in winter. It currently averages 165 records a year, with a peak of 710 in 1987. Most records are from the west coast, particularly Cornwall (and w. Ireland) but it can occur in any coastal county and even inland; numbers depend on the prevalence of westerly gales and large movements or ‘wrecks’ sometimes occur.

Flight identification Juvenile and first-winter are superficially similar to the equivalent plumages of Little Gull, both species showing a large black ‘W’ across the wings in flight. Kittiwake is much larger than Little Gull, being slightly larger than Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus. The grey mantle, scapulars and leading wing-coverts are quite dark, highlighting the extreme whiteness of the inner primaries and secondaries. Also, the black ‘W’ is better defined, particularly on the primaries: this combination produces a smarter, more contrasting ‘grey-black-white’ pattern than first-winter Little Gull. Juvenile and first-winter Kittiwakes are similar, but the juvenile has a prominent black collar across the nape, which is usually lost in first-winter plumage (when it may show a grey shawl instead). A thick black bill contrasts strongly with the white head, which has a black spot or smudge behind the eye. The underwing is snowy white, with contrasting black tips to the under-primaries; the very white primaries and secondaries appear translucent from below. By spring, it lacks the black collar and the plumage wears and fades considerably, so that the outer primaries are not as black, the mantle and wing-coverts are paler grey and the general appearance is whiter and less contrasting; later in summer, some may become severely bleached and abraded.

Identification at rest In fresh plumage, looks smart and contrasting. Identified by its thick black bill, predominantly white head, black collar (when present), rather dark grey mantle and scapulars, and large black bar across the base of the wing-coverts, extending onto the tertials. Note also the black legs, which are very short for a gull.

Flight identification A tiny gull, about two-thirds the size of Kittiwake; its small size is usually obvious, even without other species for comparison. Its feeding behaviour is remarkably tern-like, flying back and forth and dipping down to the water like a Black Tern Chlidonias niger (Kittiwake is more typically ‘gull-like’). Juvenile is easily separated from Kittiwake as the back and scapulars are completely blackish (the feathers edged pale) and this coloration extends onto the nape and neck-sides; the crown and ear-coverts are also black, quite unlike Kittiwake. As autumn progresses, however, it moults into first-winter plumage, the black feathering on the mantle and scapulars being replaced by grey, while the nape becomes white; at certain stages of moult, it can show the effect of a dark collar, suggesting Kittiwake, but this is rarely as clear-cut. First-winter retains the distinctive dark crown and ear-coverts that Kittiwake lacks; in flight, it looks less contrasting than Kittiwake, the greys contrasting less with the whites, and the black on the primaries is less clear-cut (the underwing too is a less pure white). First-summer may acquire a partial black hood.

Identification at rest Juvenile is easily identified by its predominantly black upperparts, crown and ear-coverts; this attractive black-and-white plumage suggests a large juvenile phalarope Phalaropus. First-winter is more like Kittiwake but, again, is easily separated by its black crown and ear-coverts, less contrasting upperparts, the small, delicate bill, and short pinkish-red legs.

Call A quick, throaty, tern-like ar – akar akar akar akar, recalling a squeaky toy (first-year Kittiwakes are relatively silent).

Black-winged Little Gulls There are records of atypical first-year Little Gulls with the whole upperwing black (with paler feather fringes) leaving a prominent white trailing edge; in first-winter, these show a grey mantle and scapulars that stand out as a pale ‘saddle’.

A very distinctive gull, easily identified if seen well. Despite this, many claimed Sabine’s, particularly distant individuals on sea watches, are misidentified Kittiwakes. Caution is therefore essential.

Size and structure In direct comparison, Sabine’s is noticeably smaller than Black-headed Gull and has long, thin, pointed wings; it has a tail fork but this is difficult to see at any distance. On the ground, short legs produce a pigeon-like gait. Adult summer In early autumn (August/early September) most Sabine’s passing offshore are adults and most retain a full black hood (by late autumn, this is often reduced to a large black smudge across the rear of the head). The combination of black hood, black primaries, dark grey mantle/wing-coverts and the huge white triangle on the inner primaries/secondaries permits instant recognition. The underwings are pure white, with dark tips to the primaries (often with a thick greyish bar across the greater underwing-coverts). Juvenile Dark grey-brown mantle and wing- coverts (with noticeable scaling at close range, caused by narrow whitish feather fringes) and extensive washed-out grey-brown on the nape and breast-sides. The latter two areas produce an obvious dark ‘front-end’ to the bird in flight. The brown areas, along with the black primaries, contrast strongly with the white triangle on the rear of the wing. The underwing is white but has noticeable grey shading on the under-primaries and a broad dark greyish bar across the greater underwing-coverts. Juvenile Sabine’s therefore lacks the black ‘W’, grey mantle, black collar and predominantly white head of juvenile/first-winter Kittiwake. Note that juvenile Sabine’s do not moult until they arrive in their winter quarters. Winter adult and first-summer Sabine’s Gulls do not normally occur in the Northern Hemisphere in winter, so observers should not claim a winter Sabine’s unless it is seen exceptionally well. Winter adults resemble summer birds but show a greyish or blackish ‘half-hood’ from the eye over the rear of the crown. First-years usually remain in the winter quarters during their first summer, but individuals occasionally move north in spring. At this time, such birds have a grey back and scapulars (forming a grey ‘saddle’) contrasting with the worn brown wing-coverts; they also show brown smudging on the rear crown and nape (plus a brown spot behind the eye) and pinkish legs. The overall appearance at rest may suggest a huge winter-plumaged Grey Phalarope Phalaropus fulicarius. By spring, such birds have already started wing and tail moult. By late summer, first-years are adult-like but have variable messy grey shading over the crown and/or nape, advanced birds showing a ‘moth-eaten’ hood.

Behaviour Sabine’s often flies on noticeably bowed wings. When feeding over the water, it has a flapping flight before stalling and dropping to the surface with the wings raised almost vertically.

Where and when Formerly an irregular vagrant, Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus has spread across n. Europe and is increasing. In Britain, over 1,000 pairs bred at c. 34 sites in 2010, the largest colonies in Hampshire, Kent and Sussex (Holling et al. 2012). It has also bred in Ireland since 1995. Small numbers are widespread outside the breeding season, both on the coast and inland, but it is rarer in n. England and Scotland. Adults disperse from their colonies in late June and return in March or April. Juveniles appear later, generally in July/August, and first-years linger into the summer. Large gatherings occur in some areas, with over 800 recently recorded on the Fleet in Dorset and over 600 in Southampton Water.

Size, structure and behaviour ‘Med Gull’, as it is universally known, is slightly larger, distinctly heavier, chunkier and squarer-headed than Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus (although small individuals, no doubt females, may be similar in size). On the water it looks rather neckless, flat-backed and somewhat less attenuated, while a thick, rather blunt bill is apparent at surprisingly long range. In flight it looks bull-necked and deep-chested with stiffer, less pointed wings, the latter effect perhaps emphasised on adults by their lack of a white primary wedge. It has rather a smooth, high-stepping, plover-like gait and is often markedly aggressive to other small gulls. In spring, it has a distinctive low, soft, deep but far-carrying call: eeuurr or a-ahar, rising and falling slightly (the rhythm vaguely suggesting the call of male Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope).

Plumage Adult AT REST Easily separated from Black-headed Gull by its prominently white primaries and (in winter plumage) by a large black, wedge-shaped ear-covert patch that often extends as a narrow grey shawl over the back of the head. The head pattern, however, is variable at all ages, some showing less extensive markings, while a small minority lack obvious markings altogether, looking peculiarly white-headed. In summer plumage (usually attained in March) the hood is black (brown on Black-headed) and extends further down the nape than on Black-headed (but this varies with posture). There is also a prominent broken white eye-ring. The thick, blunt bill is usually bright red and close views should reveal a black subterminal band and small yellow tip, but it may fade to orangey-red or even dull orange in autumn. IN FLIGHT A beautiful, ghostly white bird. Unlike Black-headed Gull, the underwings are pure white, while the upperwings shade from pearly grey on the mantle and wing-coverts to pure white on the primaries, lacking both the white primary wedge and black primary tips of Black-headed. The only real pitfall is the very occasional aberrant white Black-headed Gull, Common Gull L. canus or Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla (see below). Second-year As adult, but with variable amounts of black on the primaries. Most have relatively small subterminal markings, often showing as black arrowheads on the closed wing, but others have larger black primary wedges and are less easy to pick out at rest from Black-headed Gulls; however, unlike that species, they usually show prominent white within the black. First-year At rest, does not always stand out from Black-headed Gulls, but look for the combination of the black ear-covert wedge, heavy blunt bill and thickset appearance. The bill is black at first, gradually acquiring a pinkish, orangey or reddish base as winter progresses. Compared to first-winter Black-headed, the closed wing shows browner coverts, solidly dark tertials (only narrowly fringed white) and solidly dark primaries; these plumage differences, combined with the structural ones, produce a unique ‘jizz’ that is very distinctive once learnt. In first-summer plumage, they may gain at least a partial black hood (even full) and the upperparts become pale grey as the dark-centred wing-coverts and dark tertials are replaced. In flight, it has a similar pattern to first-year Common Gull and, when seen with that species, it can be surprisingly difficult to pick out but, again, look for the black ear-covert patch. The wings are, however, cleaner-looking and more contrasting than Common: the primary wedge and secondary bar are blacker, and the mid-wing panel (greater coverts and inner primaries) is clean grey; also, it lacks Common Gull’s obvious dark grey ‘saddle’ (back and scapulars), the mantle being a pale pearly grey. Most distinctive are the underwings: unlike Common, the underwings lack brown markings and are cleanly white, the only real dark being at the under-primary tips. Structural differences, particularly the bull-neck and shorter, stiffer wings, are also useful. Juvenile Even for observers familiar with first-winter Mediterranean Gulls, their first juvenile may come as a surprise. Quite unique, being closest to juvenile Common Gull at rest, as well as in flight. The whole of the upperparts, including the hindneck, are dark chocolate-brown, each feather neatly and cleanly fringed with white, producing an attractively scalloped appearance. The greater coverts, however, are plain grey, standing out as a broad, pale unmarked strip along the base of the closed wing. The breast has brown mottling, concentrated mainly at the sides. Also of note is that, unlike first-winters, the white head is relatively unmarked, with no real wedge and only a faint grey suffusion behind the eye and over the rear crown. The thick black bill is prominent against the featureless head, while the legs are also noticeably dark, reddish-black. The flight pattern is contrasting and similar to first-winter, except that the mantle is blackish, not grey. In comparison, juvenile Common is browner and less contrasting: it lacks the pale greater-covert panel, has extensive brown underpart mottling, a weak bill (with at least some pale at the base), round head, gentle expression and, most importantly, pale greyish or flesh-coloured legs. At rest, Common also looks long-winged and short-legged. Juvenile plumage of both species is quickly lost from early August onwards, during the post-juvenile body moult.

Pitfalls Hybrids When identifying second-years, always bear in mind the remote possibility of hybrid Black-headed × Mediterranean Gull, which shows characters intermediate between the two and may be confusable in a cursory glance: note particularly the hybrid’s slimmer bill and slighter build, as well as traces of Black-headed Gull plumage (such as a hint of a white primary wedge and black tips to the trailing edge of the primaries). Leucistic gulls All-white Black-headed and Common Gulls, and Kittiwakes are not unusual but their sheer whiteness, particularly across the mantle and wing-coverts, instantly separates them from Mediterranean; structural differences and bare-parts coloration are also helpful. Moulting Kittiwakes Another potential pitfall is late summer adult Kittiwakes: when still growing their outer primaries, such birds have shorter, more rounded wings than usual, with the amount of black at the tip severely reduced (perhaps suggesting second-winter Mediterranean).

Where and when A North American gull, first recorded in Britain in 1973, but currently averaging c. 60 records a year, with a peak of 108 in 1992. Most are in seen in western areas, but records have occurred throughout the country. Some have returned to the same wintering sites for many years. Although records have occurred in every month, first-years appear mainly from November to February, often remaining to summer (note that first-years are extremely unlikely before November). Adults and second-years occur mainly from November to April. All age groups also show a marked spring passage, with a peak in March and April; these are thought to be northward-bound birds that have wintered further south.

General approach Ring-billed Gull Larus delawarensis should be identified with caution, especially in first-year plumages; most are found by experienced observers who habitually scrutinise their local gull flocks. A thorough understanding of all plumages of Common Gull L. canus and Herring Gull L. argentatus, including their abnormalities and idiosyncrasies, is essential. The following details outline its separation from the similar Common Gull; differences from Herring are summarised at the end.

Size, structure and behaviour Ring-billed is always conspicuously smaller than Herring Gull, and basically resembles a large Common Gull. However, the size of all three species varies. Some male Ring-billed are noticeably larger than most Common Gulls, while small females are about the same size (comparisons should always be made with several individuals of the commoner species). Ring-billed is slightly different structurally, looking stockier, bulkier and deeper-chested, while on the water it looks flat-backed, sleek and attenuated compared to Common. The most obvious structural difference is the bill, which looks longer, noticeably thicker and more ‘parallel’: this effect is apparent even at a distance, when a thick black band (or tip) makes the bill appear rather blunt. The head is slightly more angular, less rounded than Common, but this has been over-emphasised and the head shape depends largely on attitude: when relaxed, Ring-billed can look quite round-headed. The size difference may be more obvious in flight, when Ring-billed looks distinctly longer- and broader-winged than Common. The wing-tips appear more pointed than those of Common but on adults and second-years this is emphasised by differences in the wing-tip pattern (see below). The legs are often noticeably longer than Common, resulting in a strutting walk . Ring-billed Gulls are often attracted to man and may become very tame.

Plumage Adults at rest Always remember that winter adult and second-year Common Gulls, and second- and third-year Herring Gulls, often show a prominent, clear-cut ring on the bill. The best way to pick out an adult or a second-year Ring-billed at rest is by a combination of mantle colour and tertial and wing-tip patterns. 1 MANTLE Noticeably paler than that of Common, being closer in shade to that of Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus. 2 TERTIALS Rather square and lack Common’s conspicuous broad white crescent. At close range, the tertial tips on Ring-billed are whiter, but they are narrow and do not contrast with the paler mantle. 3 PRIMARIES The closed primaries look uniformly black, with three inconspicuous white primary tips that decrease in size towards the wing-tips (unlike Common, the large white mirrors on the outer primaries are not readily apparent at rest). The pale mantle and black primaries, unrelieved by an obvious white tertial crescent, produce a pattern quite distinct from adult Common, and quite similar to adult Black-headed Gull. 4 PITFALLS Two pitfalls need to be considered: (1) unusually pale Common Gulls do exist, and (2) second-year Commons often show a narrow tertial crescent and little white in the primaries. Make sure that your ‘adult Ring-billed’ is not a second-year Common. To avoid such pitfalls, it is absolutely essential for the identification to be confirmed by other features. Structural differences, outlined above, are especially important, and pay particular attention to the bill. 5 BILL The black band should stand out clearly and cleanly, and contrast with the pale yellow base, even in winter. 6 EYE COLOUR A key difference: Ring-billed has pale irides (as well as a narrow orange orbital-ring) but the pale eye is difficult to detect at any distance. However, it usually produces a squint-eyed expression, in contrast to the dark-eyed, open-faced look of Common. 7 HEAD STREAKING Ring-billed tends to have paler, mottled head streaking, but some show quite dark streaking (this is so variable on Common as to render it of limited value in the field). 8 LEGS Often yellower.

Adults in flight If a suspected Ring-billed flies or wing-flaps, concentrate on the wing-tip pattern: Common has two large, conspicuous white mirrors right across the wing-tip, but on Ring-billed the mirrors are small, relatively inconspicuous and often confined to just one mirror on the inner web of the outer primary (the relative lack of white emphasises the more pointed wing shape). The pale mantle and wings contrast strongly with the black primary wedges so that, in flight, Ring-billed’s pattern looks surprisingly similar to that of Herring Gull; very white underwings reinforce this impression.

Second-years Similar to adult, but easily aged by the presence of dark feathering on the primary coverts. Most also show vestigial black markings on the tail and, sometimes, the secondaries (although many lack them). Conversely, some second-year Commons also show them (but usually only on the tertials). Ring-billed shows only a small white mirror on the inner web of the outer primary (often difficult to see), whereas second-year Common shows one or two obvious white mirrors. The age at which Ring-billed develops adult bare-part colouring varies: most acquire a complete black bill band and a yellow base by their first summer, although some still retain a black tip and/or a greenish base a year later; and some remain dark-eyed into their second summer.

First-years The most difficult age to identify, as many of the subtle differences are inconsistent. First-year Ring-billed has a distinctive ‘jizz’ once learnt, but it should always be identified by a combination of minor differences. Close views and detailed notes or photographs are essential, and observers should always bear in mind the possible occurrence of odd Common Gulls (for example, unusually pale individuals). All the following features (in rough order of significance) should be checked. 1 BILL The best character, being heavy, thick, ‘parallel’ and blunt-ended (Common’s bill looks slender, pointed and weedy). Usually pale orangey-pink with a prominent black tip, strangely reminiscent of the bill of first-winter Glaucous Gull L. hyperboreus (some Commons have a similar bill colour, but most have a duller, grey or greenish base). 2 TERTIALS Solidly dark brown, narrowly fringed white (on Common, paler brown, with broad white fringes, but beware the effects of abrasion). 3 MANTLE AND SCAPULARS Pale grey, lacking the dark ‘saddle’ effect of Common. Whitish tips to many of the scapulars and the retention of some dark juvenile feathering may create a more variegated pattern than Common, but the dark feathers are moulted and pale tips wear off as winter progresses. 4 GREATER COVERTS Usually appear pale grey, sometimes barred on the inners (unlike Common), producing a pale strip along the base of the closed wing and forming a noticeable pale mid-wing panel in flight. 5 HEAD AND UNDERPARTS Usually well mottled and spotted about the head (first-winters with head streaking may show a white eye-ringed effect) and more heavily mottled or scalloped below. There is often heavy dark barring or spotting on both the upper- and undertail-coverts, which Common usually lacks. Both species, however, are variable. 6 TAIL The dark of the tail-band usually extends up the outer web of each tail feather to intrude into the tail base, which usually shows delicate greyish mottling or shading (occasionally almost an all-dark tail); the tail therefore looks messy compared to Common, which shows a clear-cut band and a white base. On some Commons, however, dark also intrudes into the white, while a minority also show grey mottling at the base, so the difference is not absolute. Ring-billed has dark mottling or barring on the outer web of the outer tail feather, which Common seems to lack. 7 MEDIAN COVERTS In fresh plumage, the brown centres to the median coverts are pointed on Ring-billed, rounded on Common, but this distinction breaks down with wear and fading, and is of little use in worn plumage. 8 LEGS Sometimes quite pink on first-year Ring-billed (but may be pale greyish).

First-summer Both species fade and bleach, and eventually replace their wing-coverts and tertials with grey second-winter plumage. First-summer Commons look washed-out and pale, their outer primaries and secondaries fading to brown and the rest of the wing becoming creamy and worn, contrasting conspicuously with the dark grey ‘saddle’, particularly in flight. Ring-billed also fades but, because it lacks the dark ‘saddle’, the mantle and wing-coverts look uniformly pale grey and concolorous. Unlike Common, first-year Ring-billed soon gains a pale bill tip and, by their first summer, the bill pattern is usually similar to that of the adult.

Juveniles Full juvenile has never been recorded in Britain and Ireland. Similar to first-winter, but mantle and scapulars brown, fringed white, and the head and underparts are also heavily marked.

First-year and second-year Ring-billed may be confused with second- and third-year Herring Gulls respectively, both of which can show a prominent bill band. The easiest and most obvious difference is their size: most Herring should appear large, bulky, angular-headed, heavy-billed and meaner-looking. If in doubt, check the wing-coverts: second-year Herring shows noticeable brown barring across the wing-coverts (including the greater coverts), which first-year Ring-billed lacks; in addition, second-year Herring shows rather mottled tertials and, usually, a pale eye. In flight, second-year Herring shows fairly uniform grey inner primaries, producing a pale grey ‘window’ extending to the tips of the feathers; first-year Ring-billed has dark subterminal marks on these feathers. Third-year Herring is also easily separated as it retains traces of dark mottling on the wing-coverts, obvious vestiges of immaturity that second-year Ring-billed would never exhibit (although small amounts of brown may be retained on the leading lesser coverts); third-year Herring also has pinkish legs, whereas second-year Ring-billed usually has greenish or yellowish legs.

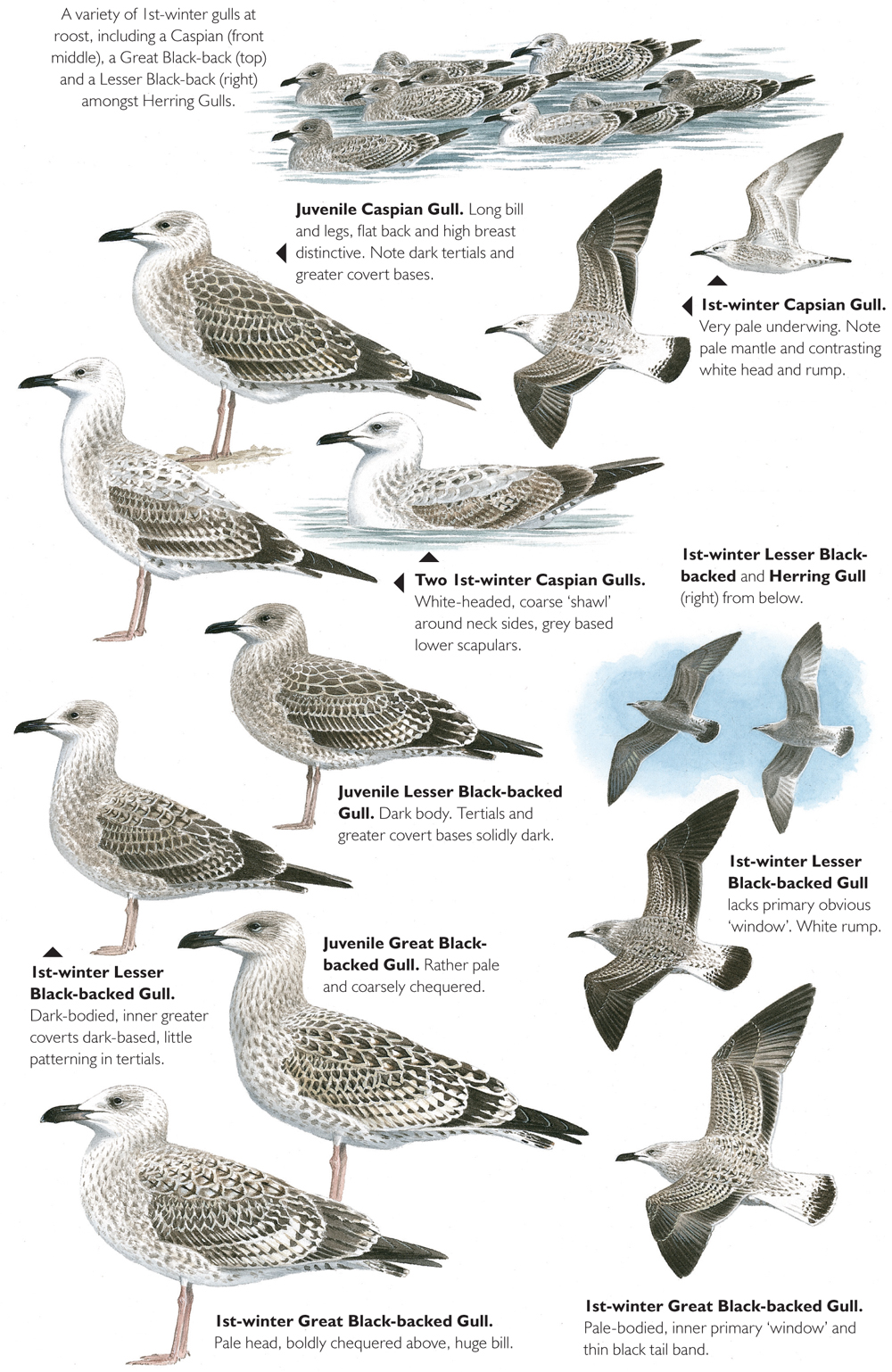

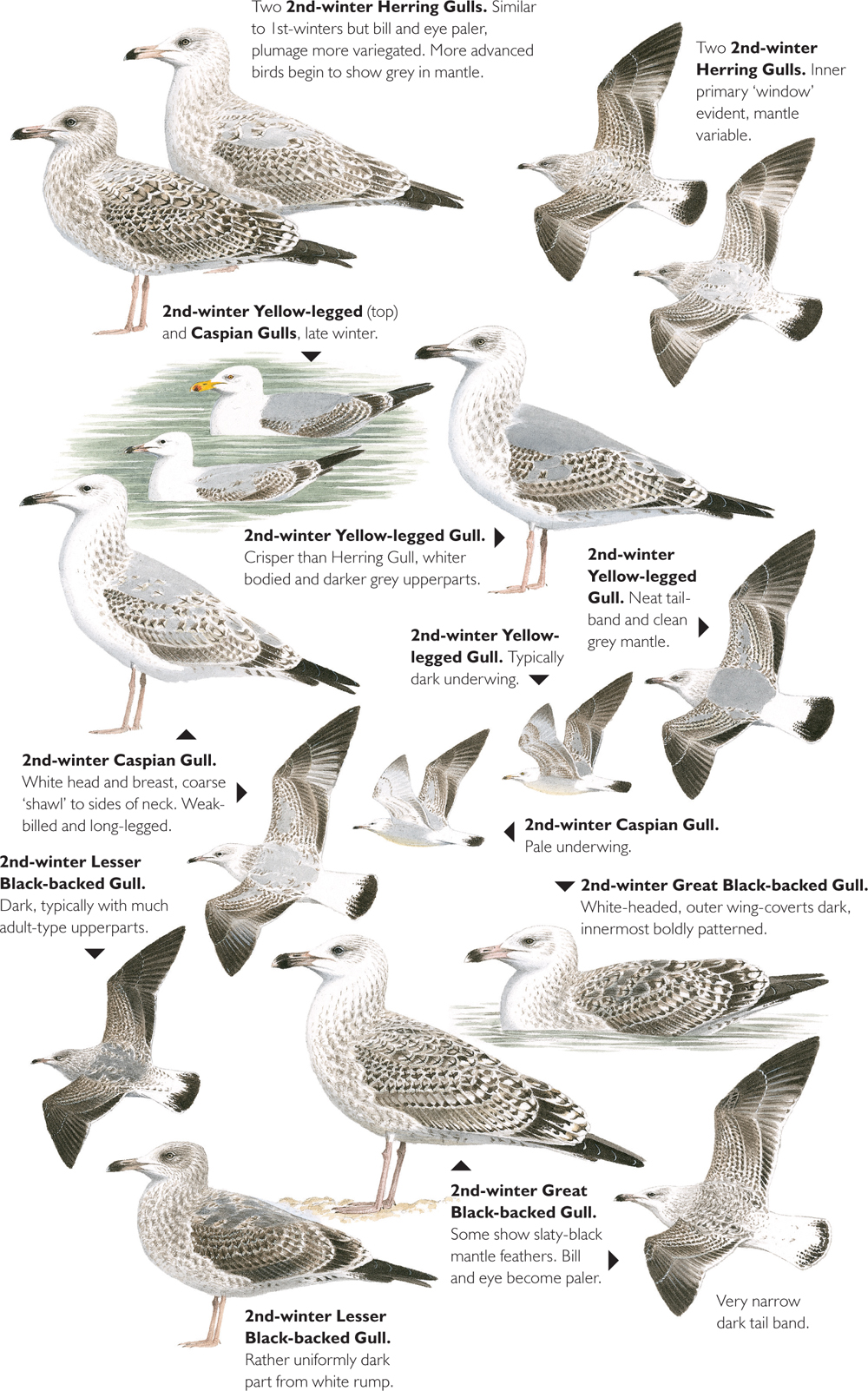

General approach Many birders find the identification of large gulls daunting. The best approach is to familiarise yourself with the Herring Gull, which should act as the yardstick. Start with adults, gradually moving on to third- and second-years, before looking at juveniles and first-years. The first real identification challenge is the separation of juvenile and first-year Herring Gulls from similarly aged Lesser Black-backed Gulls.

Ageing immature large gulls – general principles Aside from hybridisation, the reason why immature large gulls are so difficult to identify is related to three main factors: (1) moult, (2) individual variation and (3) the effects of wear and bleaching.

Moults Juvenile A large gull’s first plumage is ‘juvenile’. This is brown, heavily patterned on the upperparts and always neat and immaculate. The mantle and scapulars have brown feathers with white fringes, forming a scalloped appearance. First-year In late summer and autumn, most juveniles begin moulting into first-winter plumage. This involves just the back and scapulars, and variable numbers of head and body feathers. The back and scapulars then show anchor-shaped marks and/or cross-barring. In their first-summer, many species acquire extensive but variable amounts of greyer second-winter feathering on their back and scapulars (the shade depending on the species) while simultaneously their old juvenile or first-winter feathers become very worn and often bleached (the new greyer feathers help considerably in the identification process). Strictly speaking, however, ‘first-summer’ is not a discrete plumage, but simply the early stages of the bird’s moult into second-winter . Second-year The sequence in their second-year is similar to the first, gradually acquiring more adult-like grey feathering on their back and scapulars by their second-summer, and later the wing-coverts. Second-years otherwise retain extensive black in their primaries, primary coverts, secondaries and tail. Third-year Third-winter plumage is similar to adult, but variable amounts of brown immature feathering remain (particularly on the wing-coverts, primary coverts and tail), but this becomes increasingly limited; the bare parts may also retain signs of immaturity. Owing to their relatively consistent appearance, third-years are not usually covered in the individual species accounts below. Fourth-year Although essentially adult, many retain subtle traces of immaturity (as indeed can a few even older individuals).

Useful tips 1. Shape of juvenile primary tips A useful point to remember is that both juvenile and first-year large gulls have slightly more pointed primary tips than older birds and, when worn, these are often obviously pointed, contrasting with any newly growing, rounded, second-year feathers. This may help to age puzzling individuals.

2. Effect of moult timing on subsequent plumage type The earlier an immature gull moults, the more ‘immature-like’ the replacement feathers will be; the later it moults, the more ‘adult-like’ they will be. Thus, a first-year gull moulting in May will replace the old feathers with more immature-like feathers than a gull replacing those same feathers in August, which will grow more adult-like feathers. This explains much of the individual variation (and is presumably related to hormone levels).

3. Effect of latitude on moult timing Southerly species breed earlier than northern ones and they subsequently moult earlier; consequently, they are usually more advanced in their moults and in their acquisition of the next age of feathering. Thus, Yellow-legged and Caspian Gulls acquire significant amounts of plain grey adult-like feathers in their first-summer, whereas ‘first-summer’ Herrings, Lesser Black-backs and Great Black-backs do not. This is significant for identification.

4. Variation As indicated above, the plumage of large gulls is extremely variable and some defy accurate ageing. For example, colour ringing has revealed that a few second-winter Herring Gulls look just like third-winters.

Aberrant birds and hybrids If a gull doesn’t look right, check for anomalous features – both plumage and structural – that may suggest aberration (albinism, leucism, etc.) or hybridisation. There are no easy answers to this, except logical thought and an open mind. Olsen & Larsson (2003) and Howell & Dunn (2007) are recommended for further reading.

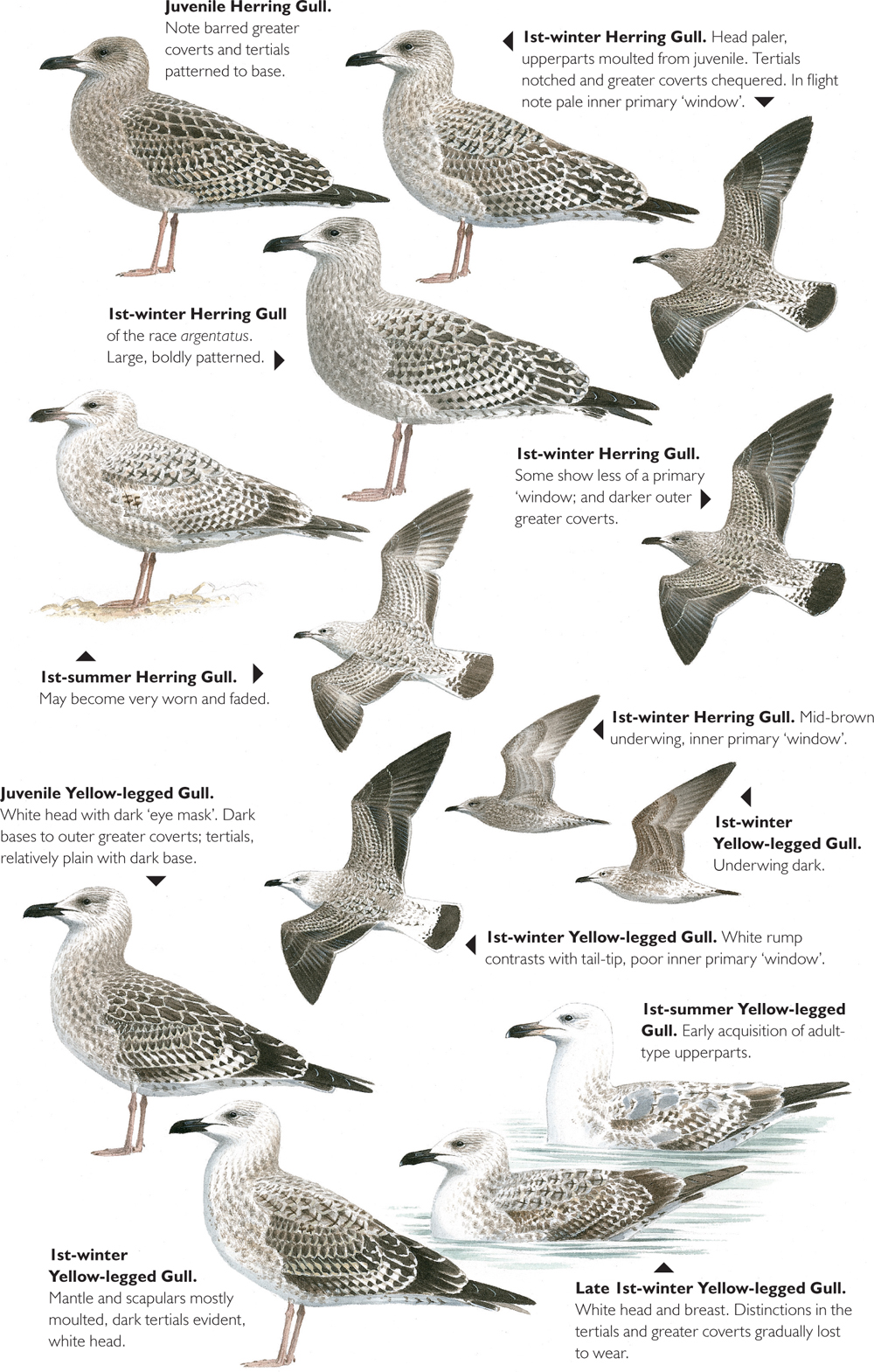

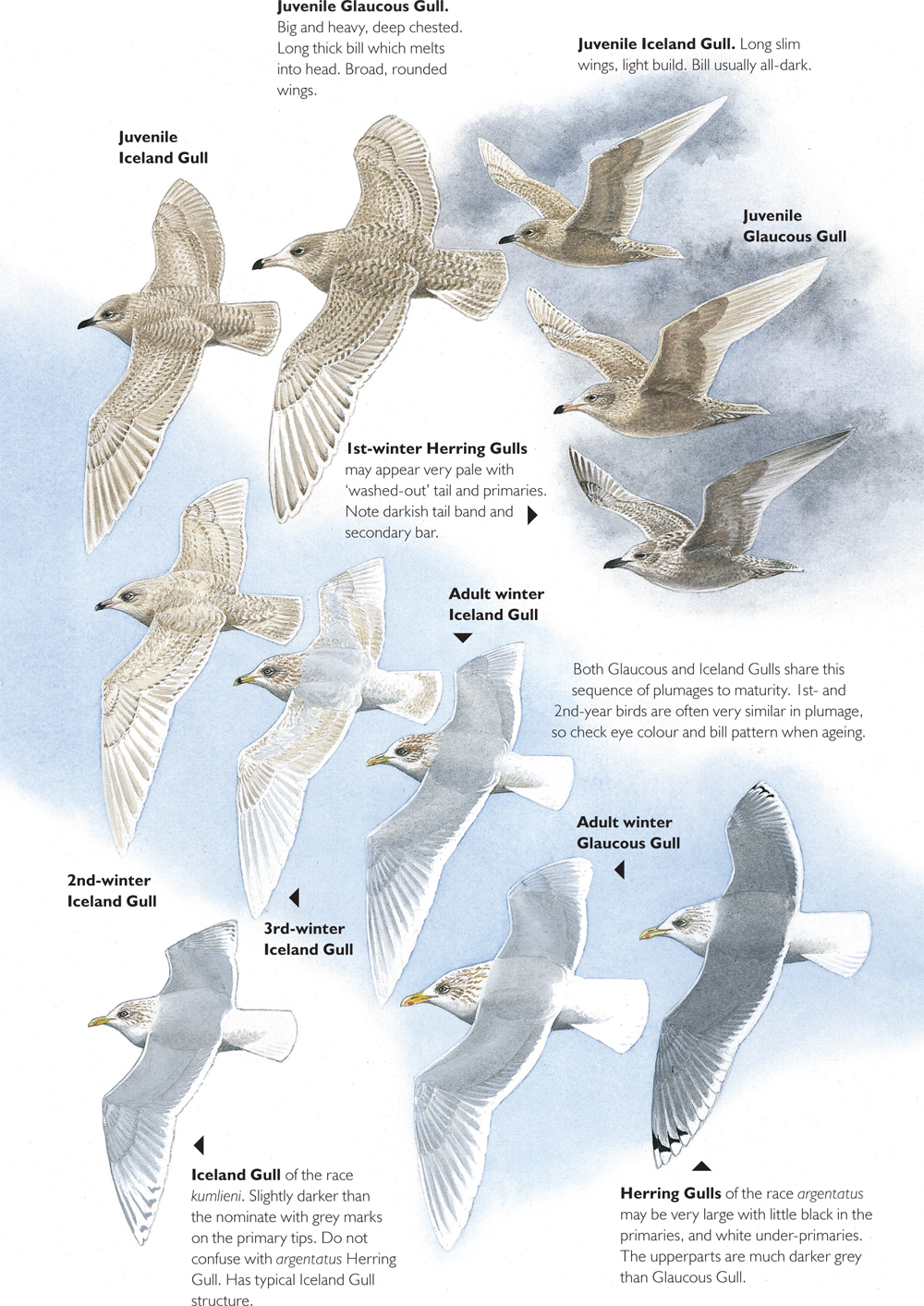

Where and when Herring Gull – the familiar ‘seagull’ of seaside towns – is a common breeding bird around our coasts and also inland on city buildings. It is more widespread in winter, when Scandinavian immigrants of the nominate race argentatus are numerous in some northern and eastern areas.

Size and structure Generally slightly larger and stockier than Lesser Black-back, with a shorter, less attenuated rear end at rest. Being a more sedentary species, the wings are proportionately slightly broader, shorter and less pointed in flight, and the body appears slightly bulkier.

Plumage Adult Easily identified by its pale grey mantle, black wing-tips and pale pink legs (note that the black in the wing-tips may become severely reduced during autumn primary moult, when the wings are much more rounded). Beware of confusion with the much smaller Common Gull (see p.207). Juvenile Similar to juvenile Lesser Black-back (see Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus) but plumage is slightly but distinctly paler, being more grey-brown, less smoky looking. The feather fringes are also generally paler. At rest, the most important differences are: 1 TERTIALS Herrings show obvious whitish notching around the fringes and tip (although there is individual variation in the exact pattern). 2 GREATER COVERTS Obviously chequered, normally lacking the thick dark bar across the inner greater coverts of most Lessers (at the base of the closed wing, nearest the wing bend). 3 HEAD Subtly paler, plainer and more bland-looking than Lesser Black-back. 4 IN FLIGHT Usually appears paler with the following differences from Lesser: (1) more obvious whitish inner primary ‘windows’, both above and below (the latter obviously translucent against the light); (2) paler brown underwing-coverts (not dark chocolate-brown), making the underwing appear paler and more uniform and (3) a slightly narrower tail-band with more white at the base; also, the tail-band does not contrast as strongly with the uppertail-coverts and rump, which are not as white looking as Lesser, being more heavily mottled. The structural differences outlined above are also useful. First-winter By late August/September, a partial post-juvenile body moult gradually introduces new mantle and scapulars feathers, which have brown anchor-shaped markings or more distinct cross-barring; when fresh, these feathers have a buff background, which soon whitens. The head and underparts also become whiter as winter progresses. First-summer Unlike Lesser Black-back and Yellow-legged, most show little if any adult-like pale grey feathering on the back and scapulars (if present, it is usually confined to a limited area on the upper back). Instead, any new feathers resemble first-winter and, as these are mixed with old, worn, first-winter feathering, individuals in active moult often look very scruffy. Note that, on the scapulars, the new feathers may be heavily barred dark brown on a whitish background. New second-winter tertials may show extensive white at the tips. The head and underparts may also retain scruffy grey streaking and mottling. By late summer, however, a minority show extensive pale grey on the back and scapulars, but these feathers usually have brown shaft-streaks and limited cross-barring. Second-year Very variable. At first surprisingly similar to first-year, with extensively scalloped or barred upperparts (but new brown tertials and greater coverts are often lightly peppered with white). Pale grey feathering gradually appears on the back and scapulars, and usually dominates by midwinter, providing an obvious difference from similarly aged Lessers. The underwings remain paler brown than equivalent Lessers, some being quite white. They gradually acquire a pale eye and an extensive pale base to the bill. If in doubt about ageing, the shape of the primary tips may be useful.

Herring Gulls breeding in Britain and Ireland are of the race argenteus. In Scandinavia, nominate argentatus takes over, becoming larger and darker towards the north, with less black in the primaries. In many parts of n. and e. Britain, most winter Herring Gulls are of Scandinavian origin. Whilst many are not safely separable in the field from argenteus, the more extreme examples are markedly different (see below). The more distinctive adults (apparently from N. Norway and the White Sea) have a darker mantle, which also tends to be colder grey. Such birds generally show reduced black in the wing-tip, large white tips to the outer two primaries, larger white primary spots at rest and a broader white tertial crescent (see pp. 230, 231 and Pitfalls). In flight, some of these dark birds are predominantly white on the underwing, often showing little black on the under-primaries. In addition, they tend to show a very heavy and angular head, heavy neck streaking in winter, a large, pale, washed-out bill and a particularly ‘mean’ expression. They also tend to be bulkier and have a pronounced tertial step. A few Baltic argentatus (formerly known as ‘ omissus’) have yellow legs, perhaps birds with Yellow-legged or Caspian Gulls in their ancestry. Immatures Some, presumably more northern juvenile/first-winters, may appear rather large, with paler plumage than argenteus (almost suggesting juvenile Glaucous L. hyperboreus or Iceland Gulls L. glaucoides). More distinctive individuals have obviously pale brown primaries with noticeable creamy-white fringes to the individual feathers.

It is possible that some such birds have Glaucous Gull in their ancestry and apparent first-generation Herring × Glaucous Gull hybrids have been seen in Britain (often called ‘Nelson’s Gull’ in North America). Smaller individuals may also suggest Thayer’s Gull (see Thayer’s Gull L. g. thayeri).

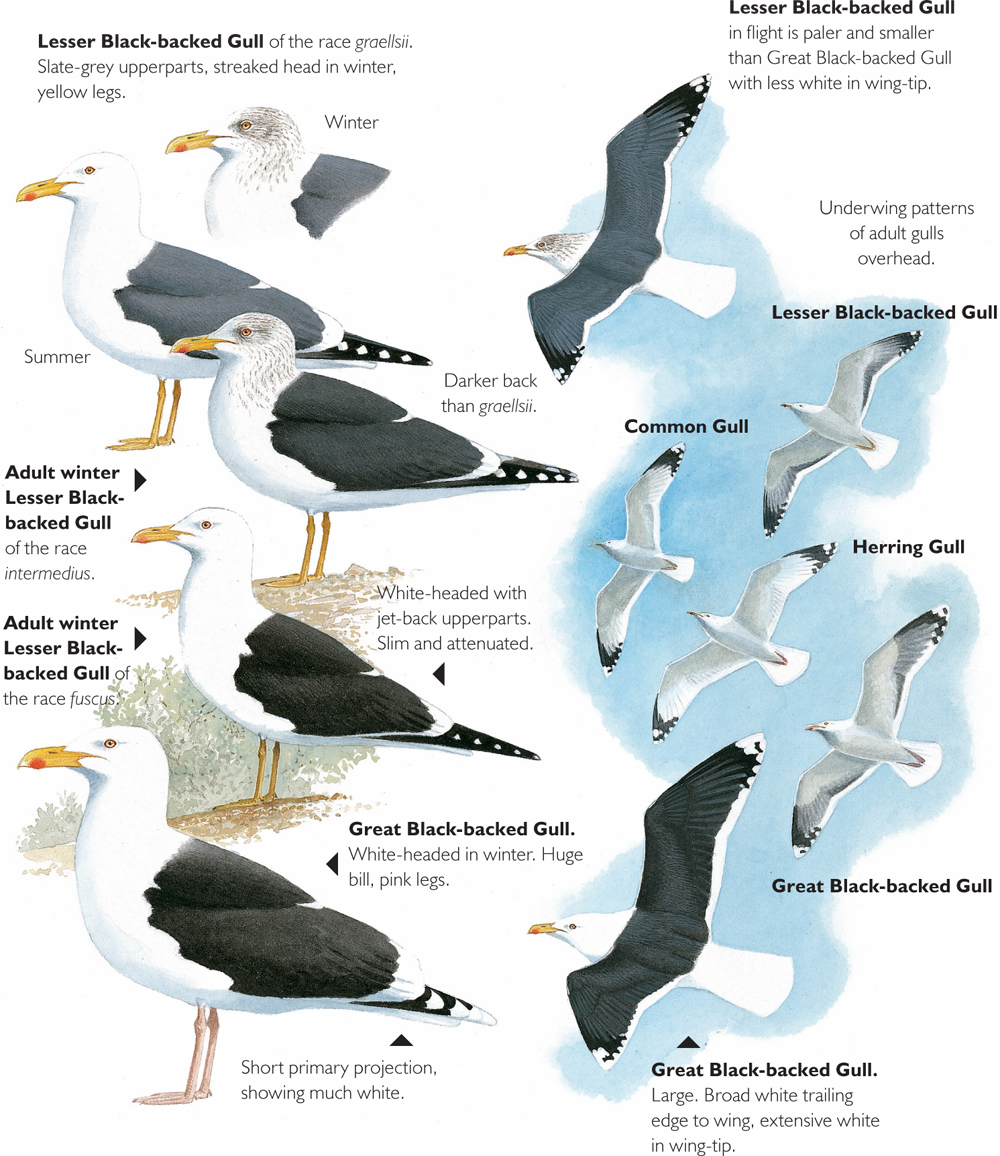

Where and when Breeds around much of the British and Irish coast (rarer on English east coast) and nests abundantly on buildings in many inland cities. Also widespread in winter (rarer in n. Scotland) with most inland, often on farmland. Lesser Black-back is strongly migratory and many head south to winter on coasts of Iberia and NW Africa (some reaching W. Africa). The darker Scandinavian race intermedius also occurs in small numbers, mainly in winter. The Baltic race fuscus – or ‘Baltic Gull’ – is on the British List by virtue of two recoveries ringed as chicks in Finland. Given that it migrates south or south-east to winter on the coasts of E. Africa, it is a relatively unlikely vagrant to Britain. However, a number of recent well-documented claims suggest that small numbers do occur, but the Rarities Committee will currently accept only records of birds ringed within the breeding range (Kehoe 2006).

Size and structure Similar size to Herring Gull, but marginally smaller and slighter, with a slightly smaller bill. Being a longer-range migrant, it has long wings, so at rest Lesser looks ‘long and low’ with long pointed primaries and a tapered rear end. These structural differences are particularly useful in flight, especially when identifying first-years or birds high overhead: compared to Herring, Lesser Black-back looks slim, with proportionately longer, narrower and more pointed wings.

Calls Adult’s calls are distinctly deeper than those of Herring Gull.

Plumage Adult British race graellsii For differences from Great Black-backed Gull, see Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus. 1 UPPERPARTS Very dark blackish-grey above, obviously paler than Great Black-back. In winter, the head and neck show heavy grey streaking, but a pre-breeding body moult from January onwards soon produces a white head. 2 UNDERWINGS Viewed from below, has dark grey across the inner primaries and secondaries (Herring is completely and obviously white in this area). 3 BARE PARTS Legs bright yellow in summer but dull creamy-yellow in winter (pale pink on Herring). In summer, the bill is often brighter than Herring’s and the orbital-ring is red (orange or orange-yellow on Herring). Juvenile 1 UPPERPARTS Compared to juvenile Herring Gulls, juvenile Lessers are distinctly dark and rather smoky looking, both above and below. The back, scapulars and wing-coverts appear rather chocolate-brown, the individual feathers being less contrastingly fringed grey-buff or dark buff. The dark tertials are relatively plain with a narrow whitish fringe, lacking the obvious notching of Herring Gull; however, many Lessers show slight notching, particularly towards the tip, while a minority show stronger whitish indentations at the tip, more similar to many Yellow-legged Gulls. Unlike Herring, at rest most juvenile Lessers show a variable thick dark bar across the bases of the inner greater coverts (i.e. those closest to the bend of the wing), this being similar to that shown by juvenile Yellow-legged Gull. 2 IN FLIGHT If in doubt, juvenile Lessers are more easily identified in flight. The dark, smoky appearance is obvious, the wing-coverts contrasting much less strongly with the black primaries and secondaries. Most importantly, unlike Herring and Yellow-legged, on juvenile Lesser’s upperwing the black of the secondaries extends right across the inner primaries, forming a solidly dark rear wing (with a narrow white trailing edge), lacking the obvious pale inner primary windows shown by Herring and, to a lesser extent, Yellow-legged Gull (Lesser shows only subdued greyish-white windows). The underwing too is dark, with chocolate-brown underwing-coverts that show relatively little contrast with the dark grey or black flight feathers. Lesser may show more black on the tail, covering all but the base; in flight this contrasts more strongly with the white rump and uppertail-coverts, which are less mottled than Herring. 3 AUTUMN JUVENILES Note that juvenile Lessers often fade considerably by early autumn, the browns becoming paler and the feather fringes and background colour to the head and underparts becoming white. Such birds may then suggest Herring Gull or, more particularly, Yellow-legged and even Caspian Gulls; nevertheless they can be separated by most of the features outlined above. First-winter By late August and September, juveniles usually begin a variable and partial body moult into first-winter plumage. They gradually acquire new feathers on the back and scapulars, showing a distinct anchor-shaped pattern; the head and underparts continue to whiten. Dark chocolate underwing-coverts are retained (paler brown on Herring). First-summer Acquired from early spring onwards. Incredibly variable, but most look quite dark as a result of the gradual acquisition of second-winter feathering, which has a dark grey background colour (albeit with variable dark chocolate-brown shaft-streaks, anchors, cross-bars and often pale fringes). Other feathers gained at this time are more like first-winter, being dark chocolate, variably patterned with darker brown. In active moult, the mix of new second-winter feathers and old worn first-winter feathers creates an extremely scruffy appearance (many old feathers become severely bleached, especially across the wing-coverts and tertials). Significantly, first-summer Herring Gulls acquire little, if any, adult-like pale grey back and scapular feathers and so remain much as first-winter, appearing paler and browner than Lessers, but often strongly barred brown across the whitish scapulars (once the new second-winter feathering is acquired). Second-year Very variable, the result of a complicated mixture of adult-like dark grey and immature-like pale chocolate feathering (both feather types variably patterned with dark brown and sometimes fringed paler). While some have extensive plain, adult-like dark grey feathering on the back and scapulars, a minority remain more like first-winters, being heavily patterned with dark anchors, diamonds and cross-bars on quite a pale background. Nevertheless, all are distinctly darker above than second-winter Herring Gulls. The tertials show more extensive white at the tip, often with a large anchor shape within the white. The eye gradually turns pale, as does the bill base. In flight, the underwing-coverts remain dark chocolate-brown. By their second-summer, the mantle and scapulars become predominantly dark grey, forming a distinct ‘saddle’, and many also show extensive dark grey on the upperwing-coverts, increasing considerably by late summer. The head and underparts become white and the bare parts often brighten considerably.

Scandinavian races

Adult intermedius Lesser Black-backs become darker towards the north and east. As its name suggests, Scandinavian intermedius is intermediate in shade between British graellsii and nominate Baltic fuscus, appearing distinctly darker and blacker than graellsii. Both its structure and the timing of its moults are similar to graellsii.

Adult fuscus Classic individuals are distinctly or even strikingly smaller and slighter than graellsii, with a smaller, slimmer bill, more domed head, shorter legs and long, scissor-like primaries (it has long slender wings in flight). Their jizz may be reminiscent of a smaller gull, such as Common Gull L. canus. The upperparts are virtually black, similar in shade to Great Black-back, showing little contrast with the black primaries, which have only a small white mirror on the inner web of the outer primary. Fuscus also has a whiter head in winter, with light grey streaking confined to the crown and hindneck.

Moult Differences are particularly significant: graellsii and intermedius have a complete post-breeding moult from mid May to December, with their primary moult commencing anytime between May and August. Apart from perhaps the innermost one or two primaries, fuscus does not commence its primary moult until arrival in its winter quarters, from October to April. Consequently, any late summer/autumn fuscus seen in Britain is likely to have old and worn primaries until at least October, by which time local graellsii will have new, fresh primaries. Winter fuscus should be in active primary moult, whilst in spring the primaries should be new and fresh at a time when graellsii’s are starting to wear. However, great caution must be taken when identifying a potential fuscus in Britain. In particular, the effects of the light must be carefully considered, particularly at evening roosts (in certain lights even graellsii can look very dark). There is also intergradation between fuscus and intermedius while, apparently, some small female intermedius closely resemble fuscus. It has to be accepted that any apparent fuscus seen in Britain is unlikely to make it beyond the level of ‘possible’ or ‘probable’, unless of course it carries an identifiable ring.

Where and when Breeds fairly commonly, mainly on rocky coastlines, right around Britain and Ireland, except along the British east coast south of the Firth of Forth. More widespread in winter, when Norwegian immigrants are common in the east, penetrating well inland. Small numbers of local breeders may also feed throughout the year on inland lakes and reservoirs.

Size and structure Fundamental to its identification. A huge, bulky brute of a gull, with a large head, deep chest, often a pronounced tertial step and a somewhat truncated rear end. Conspicuously larger than all other gulls and always dominates them when feeding. Males are larger than females, but most are c. 20% larger than Lesser Black-back and, more importantly, about twice as heavy. In comparison, Lesser is rather slender, with long primaries that at rest produce an obviously tapered look to the rear end (but wings appear shorter during autumn primary moult). Great Black-back’s deep and powerful bill is always conspicuously larger than that of Lesser Black-backed and Herring Gulls, with a rather bulbous tip and prominent gonydeal angle. Note also the small beady eye (looks dark at any distance), set well back on the head. In flight, it appears slow, lumbering and pregnant-looking, with relatively rounded wings and slow wingbeats (its 1.5m wingspan is larger than that of Common Buzzard Buteo buteo) . In comparison, Lesser Black-backed’s wings are long, narrow and pointed although, in the absence of direct comparison, Great Black-backed’s can look proportionately somewhat shorter.

Calls Adults’ somewhat muffled calls are loud, deep, powerful and often bellowing.

Plumage Adult If seen well, separation from Lesser Black-backed is not difficult but, if accurate size assessment is not possible, confusion is surprisingly easy, especially if poor light affects the mantle colour. 1 UPPERPARTS Great Black-back is virtually black above, readily separating it from the British race graellsii of Lesser Black-back (Scandinavian Lesser Black-backs – intermedius and the rare fuscus – are darker above). At rest, Great Black-back has a thicker and more prominent white tertial crescent. 2 LEG COLOUR When in doubt, concentrate on size, structure and leg colour, Great Black-back having flesh-coloured legs (Lesser Black-back yellow, bright in summer but duller in winter when the yellow can be difficult to discern in weak light). 3 HEAD COLOUR IN WINTER Great Black-back retains a largely white head in winter (any markings are faint) whereas graellsii Lesser has a heavily streaked head until at least December. 4 IN FLIGHT Great Black-back is blackish right across the wings, whereas the paler wings of graellsii Lesser contrast with the blacker primaries. Great Black-back has large white tips to the outer two primaries forming a diagnostic and conspicuous white spot at the wing-tip (Lesser usually has much less obvious subterminal mirrors). Greater also has a broader white trailing edge to the wing that contrasts much more strongly with the blackish upperwings. The under-primaries and under-secondaries are noticeably dark grey. Juvenile Most likely to be confused with similarly aged Herring Gulls (and even more similar to juvenile Yellow-legged Gull, which see), so correct size and structural evaluation is essential. 1 BILL Pay particular attention to the large black bill, which usually contrasts strongly with the predominantly white head (lightly streaked around and behind the eye). 2 UPPERPARTS Plumage neat and immaculate and appears much ‘cleaner’ than first-year Herring, with a buffy-white background colour (gradually wearing whiter). The wing-coverts are distinctly chequered with chocolate-brown, whereas the mantle and scapulars are plain brown, each feather neatly fringed with white (Herring’s underparts and upperparts are browner, the latter with a less contrasting, duller ground colour, but some pale individuals can look more similar to Great Black-back). The tertials show broad white tips and fringes. 3 IN FLIGHT The rather pale upperwing-coverts contrast quite strongly with the black primaries and secondaries. Most useful in flight is a rather narrow tail-band which, at close range, often has a series of narrow black bars in front of it and thus appears ill-defined (tail-band solidly brown or black on Herring and Yellow-legged Gulls). Unlike Herring, the tail-band contrasts strongly with the white base, uppertail-coverts and rump, which are only lightly mottled. First-year 1 UPPERPARTS Following partial post-juvenile body moult in autumn, the head and underparts become even whiter and the white-fringed juvenile mantle and scapular feathers are gradually replaced by first-winter feathers that show brown anchor-shaped marks on a buff background, with noticeable white fringes (producing a more barred impression). 2 BILL Black throughout the first winter, but often acquires a pale tip and base in the first summer (Herring usually acquires a paler base during its first winter). Second-year 1 PLUMAGE Becomes even whiter on head and underparts. Initially very heavily patterned above, often with obviously all-dark greater coverts. It gradually acquires obvious blackish feathering on the back and scapulars, allowing easy identification. 2 BILL Becomes paler and pinker, with black only at the tip, and the eye gradually turns pale.

References Olsen & Larsson (2003), Howell & Dunn (2007).

Background Some of the greatest recent advances in bird identification have related to the large gulls. It has always been known that the widespread and familiar ‘Herring Gull’ occurs in various forms across the Northern Hemisphere, but recent developments in the analysis of their DNA have indicated that, what was formerly considered one species, is at least six. These can be divided into two clades (groups of closely related species that share a common ancestry). The North Atlantic clade contains European Herring Gull, Yellow-legged Gull and Armenian Gull L. armenicus as well as Great Black-backed Gull L. marinus, all evolving from a common ancestor in the North Atlantic. The Aralo-Caspian clade (named after the Aral and Caspian Seas in SW Asia, a past hub of gull evolution) contains Caspian Gull, all races of Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus, the various Siberian forms of ‘Herring Gull’ and, remarkably, American Herring Gull L. smithsonianus, the ancestors of which apparently colonised North America not from the Atlantic, but from Asia. As far as we in Britain are concerned, the most significant changes relate to Yellow-legged and Caspian Gulls. It has long been known that the former is a regular late summer and winter visitor from the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic coasts of Iberia and France. Caspian Gull, which breeds principally in SE Europe and SW Asia, was officially split as recently as 2008. In recent years it has started to spread north-west and is now breeding as close as Poland. The problem is that, as with many expanding species, the pioneers are interbreeding with a closely related species, in this case Herring Gull. Although classic Caspian Gulls are fairly distinctive, it is this hybridisation that makes it such a difficult and controversial species to identify.

Where and when Most occur in late summer (July to September) with smaller numbers remaining until late winter (by spring and early summer, only a few immatures usually remain). They occur both on the coast and inland, particularly on rubbish tips and reservoirs. Since 1995, one or two pairs have bred in s. England.

Size and structure Older birds are usually located by their darker grey mantle (see below) but structural differences are also significant. Somewhat larger and more powerful than Herring Gull and males may be particularly big, clearly intermediate in size between Herring and Great Black-back. The bill is usually longer, heavier and more bulbous than Herring’s, with a deep and rather blunt tip; some large males have a particularly long and heavy bill. It also tends to be deeper-breasted and rather long-legged, sometimes producing a distinctly gangly impression (often adopts a very horizontal stance with a bulbous breast and long legs). In flight, it has noticeably long, pointed wings and glides on arched wings, rather like a skua. Those that occur in Britain are of the w. Mediterranean race michahellis, but some resemble so-called ‘ lusitanius’ from w. Iberia (see ‘Lusitanius’ Yellow-legged Gulls).

Plumage A useful point to remember is that, as they breed further south, Yellow-legged Gulls nest earlier than both Herring and Lesser Black-backed; consequently, at each plumage stage young birds mature significantly earlier than equivalent-aged Herring Gulls.

Adult Superficially similar to Herring Gull, but remember that it shares many features with Lesser Black-back. When separating adults, the following should be looked for (in approximate order of significance): 1 MANTLE Clearly a darker ‘mid grey’, intermediate between graellsii Lesser Black-back and argenteus Herring (similar, in fact, to Common Gull L. canus, but warmer). 2 LEGS Yellow, bright in summer, but paler and washed-out in winter (when the colour can be difficult to determine). 3 HEAD SHAPE At rest looks bulbous with a thick neck but, when alert, may show a rather small, flat head and distinctly long neck. 4 HEAD STREAKING Lacks Herring Gull’s heavy head streaking in winter, instead showing only limited light grey streaking in autumn and early winter on the crown, perhaps on the nape and most obviously a stronger backward-pointed area around and behind the eye. This difference is valid only until late December/January onwards when both Yellow-legged and argenteus Herrings start to acquire their white summer head colour. However, early moulting Yellow-leggeds often stand out as sleek, smart and contrasting amongst winter-plumaged Herrings. 5 BILL Brightly coloured with a large red spot; it may acquire a narrow black band in winter. 6 ORBITAL-RING Red, like Lesser Black-back, producing a beady-eyed effect at a distance (yellow or orangey-yellow on Herring). 7 UPPERWING In flight, tips more extensively black than Herring; also, the black wing-tips are cut off more squarely and show little white at the tip (two mirrors on P9 and P10). 8 UNDERWING Dusky-grey across the under-secondaries and inner primaries (not as dark as Lesser Black-back); Herring is all white in this region. 9 MOULT Earlier than Herring, with extensive primary moult from July to early September. Primaries are practically fully grown by September, when local argenteus Herring’s are usually still short and partially grown. 10 CALLS Distinctly louder and deeper than those of Herring Gull (and Lesser Black-back), often recalling Great Black-back.