Where and when As a breeder, Long-eared Owl Asio otus is widespread but thinly distributed throughout Britain, usually inhabiting coniferous woodland (but sometimes even nesting in hedgerows); in Ireland, it is the commonest owl and, in the absence of competition from Tawny Owl Strix aluco, is found more frequently in broadleaved woodland. Short-eared Owl A. flammeus breeds in open country, mainly in Scotland, Wales, and n. and e. England. Both species are more widespread in winter, when Short-eared Owls move into lowland areas; variable numbers of Continental immigrants swell the numbers of both species, October being the best time to encounter newly arrived migrants.

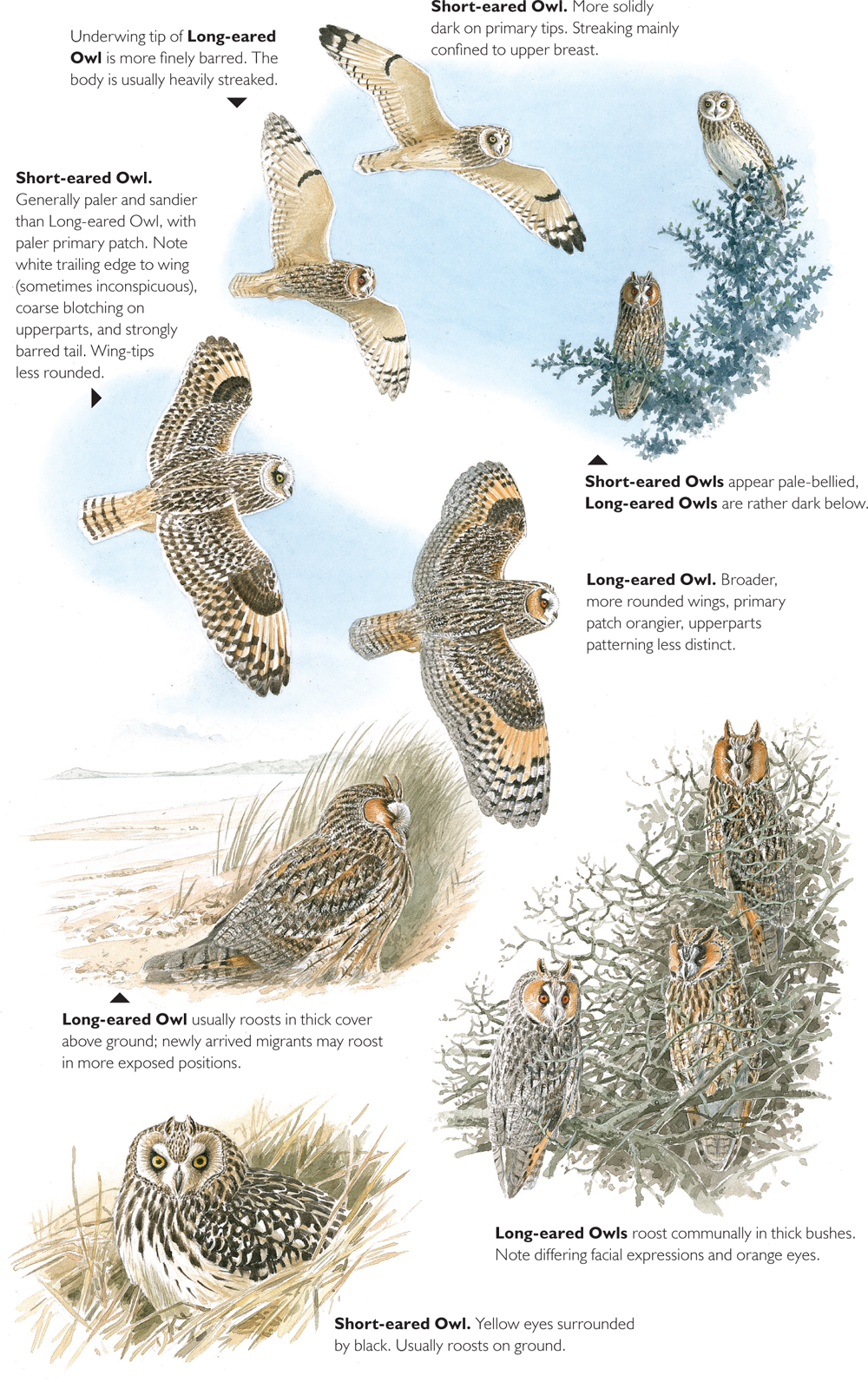

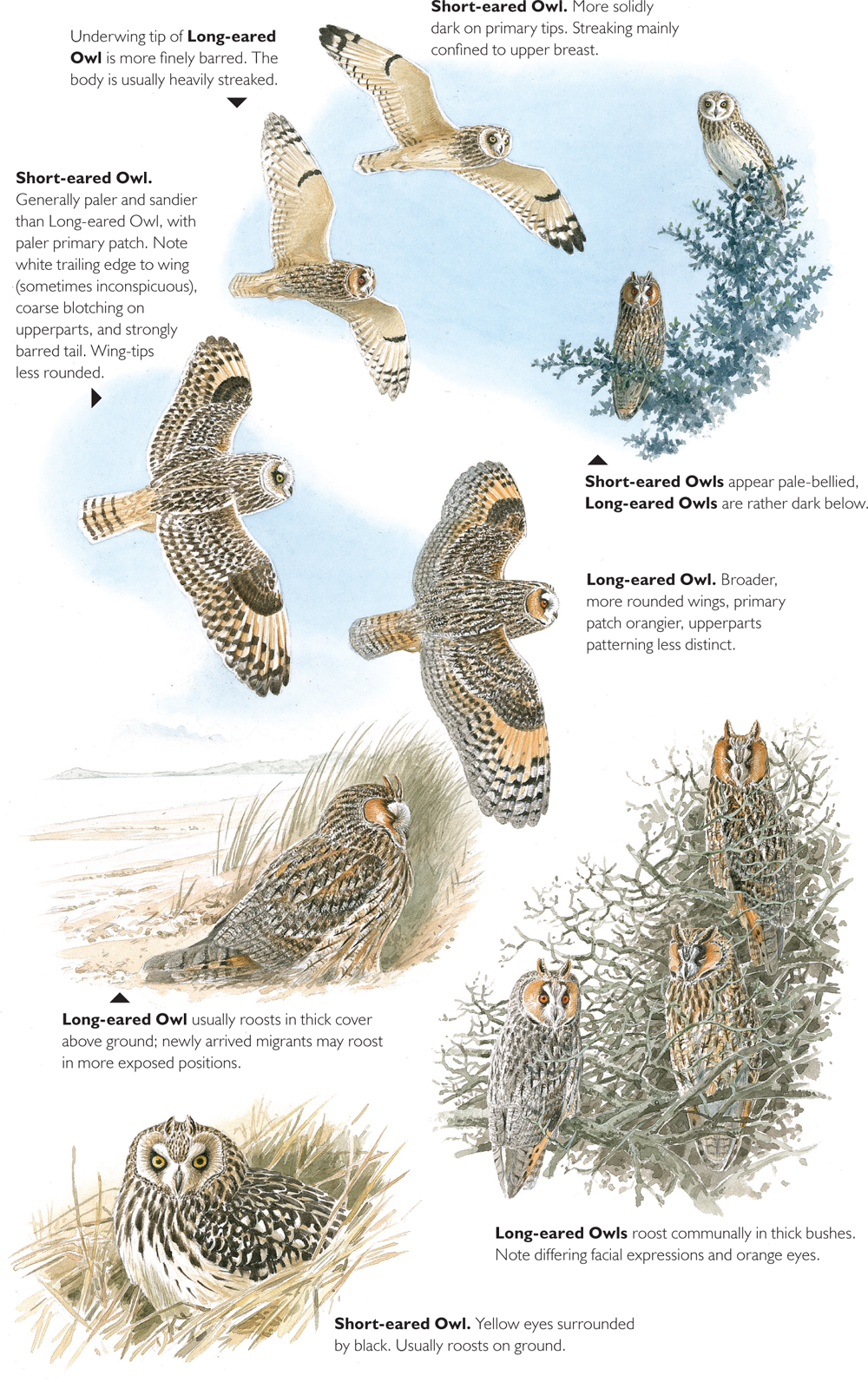

Habitat and behaviour Such differences are generally the first clue to identification. Short-eared is frequently seen in broad daylight, particularly on winter afternoons, hunting over rough ground; it usually roosts on the ground in rough vegetation. High-flying Short-eareds (e.g. migrating birds) are very distinctive, flying with the wings ‘pushed forward’ on deep, flappy wingbeats, but gliding with the wings held in a shallow V. Long-eared is more or less strictly nocturnal, not usually hunting in broad daylight; it typically roosts in conifers, thick hedgerows or bushes, often at some height; when flushed, it will fly off silently through the trees and quickly disappear (often roosts communally in favoured areas). The biggest identification problem arises with migrants, which can appear at coastal migration spots at any time of day. In such circumstances, Long-eared may settle on the ground when trees or bushes are unavailable. Conversely, Short-eareds occasionally roost in trees, even at some height.

Identification at rest Long-eared is a slim, upright owl, usually found in a conifer or thick bush, when often quite approachable. Easily identified by its long ‘ear-tufts’ and thick vertical dark lines running down the face to the bill; it also has a pale eyebrow and a rather orangey facial shield. The eyes are brilliant orange (best seen when flashed open if startled) and the underparts are heavily streaked and barred down to the belly (some are less heavily streaked). Short-eared is generally paler and less upright, usually seen sitting on the ground or on a fence post. It has short ‘ear-tufts’ and yellow (or orangey-yellow) eyes which, unlike Long-eared, are surrounded by circular, panda-like black patches; also important is that the underparts streaking is confined mainly to the upper breast.

Identification in flight General plumage tones Both species are very variable, but Long-eared is typically darker and browner than the sandier, buffier Short-eared. Because of its darker plumage tones, Long-eared usually appears a more uniform, less contrasting bird. Some Short-eareds are, however, darker than others, while some Long-eareds are particularly pale, almost whitish-buff on the underparts. 1 UPPERWING Both show a pale patch on the upper-primaries. On Long-eared this is a darker rich orangey-buff to rusty colour whereas, on Short-eared, it is paler, sandy-buff to almost white, and therefore more obvious. The upperwing of Short-eared is generally paler than Long-eared’s, the upperwing-coverts being more mottled than streaked, giving a less uniform appearance. The paler coloration of Short-eared also means that the dark carpal patches are more obvious than on Long-eared, while the primary and secondary barring also appears stronger and more contrasting (on Short-eared, the primary barring continues onto the secondaries whereas, on Long-eared, barred primaries give way to finely barred secondaries). Short-eared has a pale trailing edge to the wing (but on particularly pale Short-eareds this can be surprisingly difficult to see). Long-eared usually lacks a white trailing edge but some individuals can in fact show this feature, but it is never as clear-cut as on Short-eared. 2 UNDERWING Both have pale underwings with a dark carpal patch. Long-eared’s primaries are crossed by three to five dark bars whereas on Short-eared the tips of the outer primaries appear more solidly black. 3 TAIL On Long-eared, the upper tail is generally more closely barred on a darker background, producing a more uniform appearance than on Short-eared, which has four or five prominent bars on a paler, sandier background. 4 UNDERPARTS Heavy streaking is confined mainly to the upper breast on Short-eared creating a strong breast-band (although it does extend more finely onto the belly); on Long-eared, heavy streaking extends onto the belly, creating an overall darker, more uniform impression (although on some the streaking is distinctly weaker lower down). 5 STRUCTURE Long-eared has shorter and broader wings than Short-eared, with the tips broader and more rounded; it is also proportionately shorter-tailed. Short-eared’s wing is narrower and more tapered, emphasised by the fact that it is held more forward than Long-eared’s.

Calls Short-eared’s most familiar call, given by both sexes, is a hoarse, high-pitched bark, heard mainly on the breeding grounds. It also gives a low hissing screech, rising towards the end. Males have a wing-clapping display flight, as well as a hollow boo-boo-boo-boo advertising call (BWP). In early spring, male Long-eared gives a low-pitched, flat, dove-like cooing oo repeated at intervals of c. 2.5 seconds (BWP); it is rather quiet, but audible for some distance. It also gives a variety of other calls in the breeding season, including nasal buzzing, wheezing and barking noises. Begging young have a very distinctive, far-carrying, clear, mournful eee-oo, like the squeaking of a rusty hinge. This is heard from late May to July and is often the first indication of the presence of breeding birds.

References Davis & Prytherch (1976), Kemp (1982), Robertson (1982).

Where and when Common Swift is a familiar and common summer visitor, mainly from late April to late August, with stragglers into October or even November. Alpine Swift is a rare but annual vagrant, mainly in spring, currently averaging 14 records a year (with a record 27 in 2002). First recorded in 1978, Pallid Swift was formerly a gross rarity, but it is currently averaging four records a year (with as many as 16 in 2004). Partly as a result of it being double-brooded, Pallid Swift is prone to periodic influxes during southerly winds in late October and early November. Similarly, there have been very early spring records (late March) with further occurrences right through the spring and summer. Whilst not all early or late swifts will prove to be Pallid, it is clearly worth checking such birds very carefully.

Before identifying a vagrant swift, it is absolutely essential to eliminate the possibility of an aberrant Common Swift, examples of which are not infrequent. Such birds may show white feathering, those with white on the rump sometimes suggesting the very rare Little A. affinis, White-rumped A. caffer or Pacific Swifts A. pacificus. It is, therefore, essential to take very detailed notes of any swift with a white rump, concentrating in particular on structure, and to look for traces of white feathering elsewhere on the body. The aberrant individual illustrated on p. 260 is loosely based on a bird seen in Dorset in 1983. Aberrant pale, sandy Common Swifts have also been recorded, and these may suggest Pallid (see Pallid Swift Apus pallidus).

When faced with a vagrant Alpine Swift, check two things to eliminate an aberrant Common Swift: 1 be sure to accurately evaluate its size (Alpine Swift is about 1½ times the size of a Common Swift) and 2 make sure that the upperparts are pale (they should be similar in tone to those of a Sand Martin Riparia riparia). However, plumage tone varies according to the light, and Alpine Swifts can sometimes look as dark as Common Swifts, especially when high in the sky. The white belly is always conspicuous, but the white throat can be difficult to see. Long, slim wings produce slower, more deliberate wingbeats and create a rather languid flight action, with more gliding; this is very obvious even at a distance. At other times, its fast, purposeful flight may even suggest Hobby Falco subbuteo. Alpine Swift has a distinctive call: a long, slow, dry trill that tapers off at the end; however, this is unlikely to be heard away from its Continental breeding areas.

Pallid Swift is a real ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ species: sometimes easy to identify, sometimes difficult to the point of being impossible. This is because its identification hinges on good views and the accurate assessment of subtle plumage tones. As this is entirely light-dependent, perfect light is required. Paradoxically, bright sunshine is one of the worst conditions, particularly if the bird is high in the sky. Pallid is best viewed in dull, flat light, preferably against a dark background. In such conditions, the following differences (based on Harvey 1981) should be carefully checked. 1 PLUMAGE TONE Pallid has distinctly paler, milkier plumage than Common Swift. 2 WING PATTERN Note particularly the dark outer primaries and leading edge of the underwing contrasting with the rest of the underwing, which is paler. This effect is mirrored on the upperwing, where the greater coverts and secondaries can stand out as being quite noticeably paler, even translucent when seen from below (although Common can show quite silvery upper-secondaries in certain light). 3 BODY COLOUR Its slightly darker body contrasts with the paler underwings, while the darker mantle produces the effect of a slightly darker ‘saddle’. 4 FEATHER FRINGES Pale feather fringes on the underparts (particularly on the flanks) may be obvious at close range, forming pale scaling. 5 HEAD The forehead and throat are noticeably white, the throat being larger than on Common Swift; in consequence, the dark eye is more noticeable. 6 WING-TIP SHAPE On Common Swift, the outer primary is longest, producing a sharply pointed wing; on Pallid, the outer two primaries are the same length, producing a slightly blunter wing. This, combined with the slight broader base to the wing, produces somewhat more paddle-shaped wings than Common. Although subtle, this can be surprisingly obvious when looked for; conversely, at any distance they can appear to have pointed wings just like Common. 7 TAIL-FORK Slightly shallower on Pallid. 8 CALL Pallid gives a markedly disyllabic cheeu-ic or cheeur-ic, slightly lower-pitched than Common, with the second syllable slurred upwards. However, this is unlikely to be heard away from the breeding areas. Common Swifts can in any case also give disyllabic calls, even when feeding away from their breeding sites, but these tend to be not as strongly disyllabic as Pallid. Differences in their flight actions are similarly subtle but, whereas Common sweeps back its wings and has strong wingbeats, Pallid perhaps has a slightly more fluttery action with less of a tendency to ‘whip back’ its wings in normal flapping flight.

A further complication is provided by the paler Siberian race of Common Swift pekinensis, which apparently shares many of Pallid’s features (large pale throat, pale scaling on the body, and pale and dark contrasts to the upperwing; Fraser et al. 2007). Although this form has not been recorded in Britain, it is a potential vagrant. However, as its separation from Pallid has still not been resolved, this subspecies remains something of an unknown quantity. Wing shape may be significant (more pointed, as nominate Common Swift).

References Fraser et al. (2007), Harvey (1981).