General characteristics of shrikes Shrikes are conspicuous birds, selecting prominent perches such as telephone wires, fences and the outermost branches of bushes. They survey the surrounding area, watching for prey like a raptor. They pounce on large insects, amphibians, small mammals and birds, often impaling larger victims on thorns. They can, however, be surprisingly secretive and difficult to find (usually because they are simply out of view). Their tails are very mobile, frequently raised, dipped, flicked, swished and wagged. Most species have a variety of harsh, rasping, screeching or chacking calls.

Where and when Formerly a common summer visitor, Red-backed Shrike became extinct as a regular British breeding bird in 1988. Since then, breeding has been erratic, mostly in Scotland. It remains a scarce late spring and autumn migrant (mid May to June and mid August to October, occasionally into November) mostly on the east coast and in the Northern Isles. It currently averages 200 records a year.

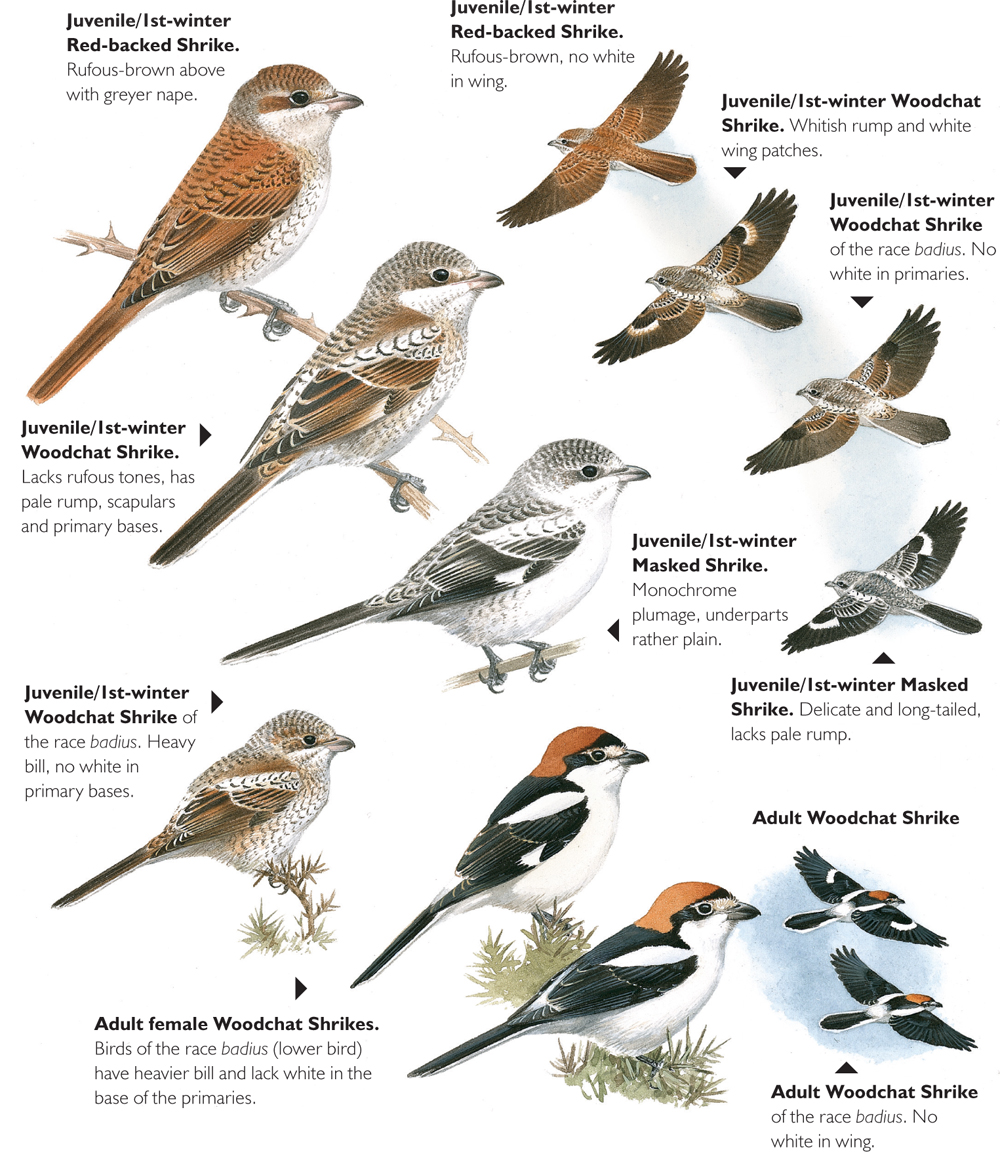

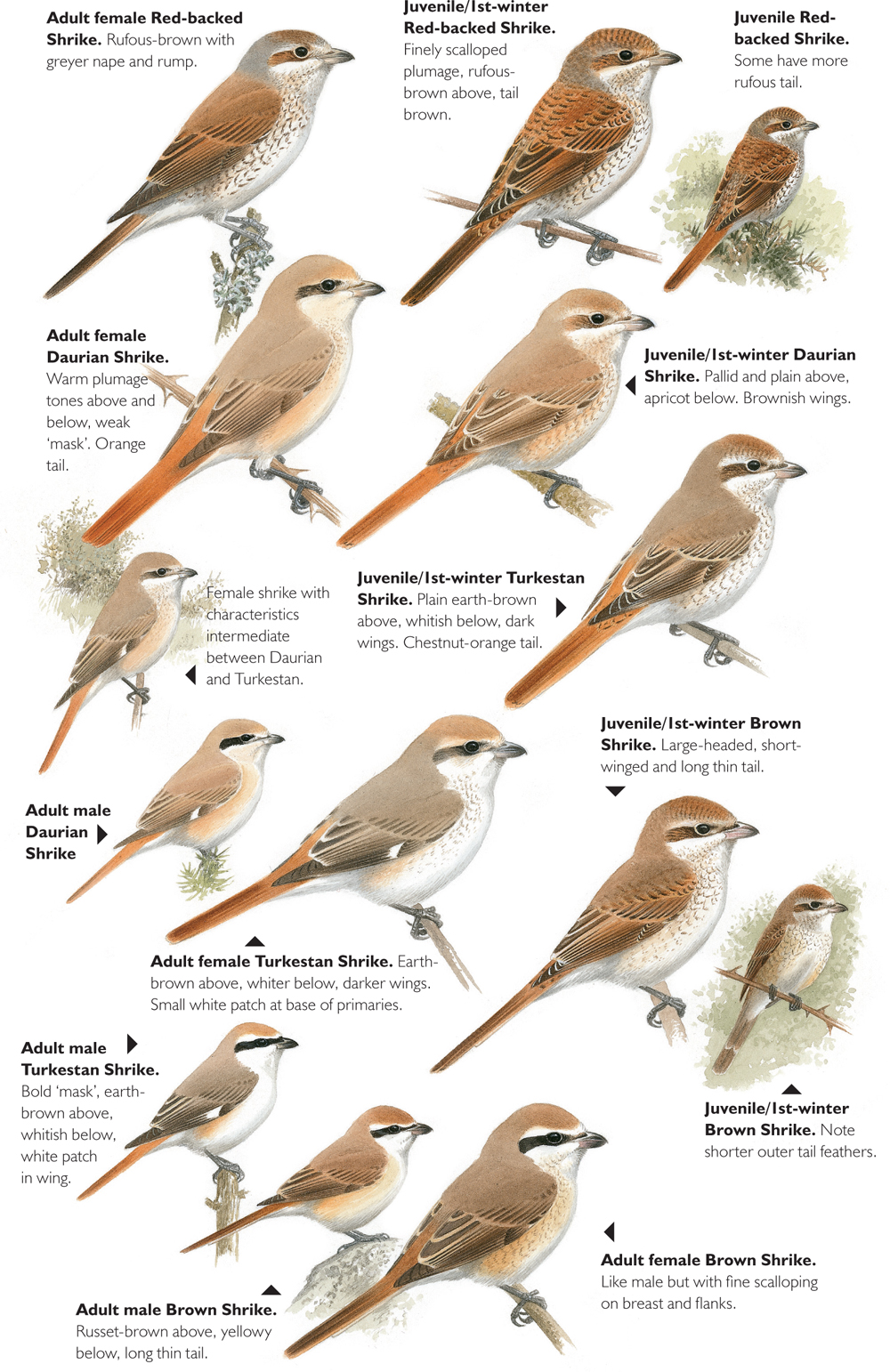

Plumage Adult male With its grey head, black facial mask, reddish back and white bases to the outer tail, the adult male is easily identified. Adult female Females are less distinctive, being plain rufous-brown or warm brown above, with a greyer crown, nape and rump; the underparts are heavily scaled on a whitish background. The head has whitish lores and supercilium, and a dark brown mask; they are, however, variable, some looking somewhat more ‘male-like’ than others. Juvenile/first-winter In full juvenile plumage, Red-backed Shrikes are rufous-brown above (often with a greyer nape and sometimes crown); the white underparts are lightly scalloped with grey, the upperparts heavily scalloped dark brown and buff (subdued with wear). They show an ill-defined whitish supercilium and dark brown ear-covert patch. Remarkably, their post-juvenile moult begins shortly after fledging, sometimes before their wing and tail feathers are fully grown (BWP). This is partial and highly variable, involving the body feathers and some wing-coverts. Consequently, by the time they migrate, their plumage is a variable mixture of scalloped juvenile and plain rufous-brown first-winter upperpart feathering. Like adult females, they often show a strong grey tint to the nape. Note that some females and immatures have a distinctly redder tail, which may suggest Turkestan Shrike (see Turkestan Shrike Lanius phoenicuroides).

Where and when ‘Isabelline Shrikes’ have been almost annual in Britain since the late 1970s (89 records by 2011 with as many as nine in 2011). Two forms occur here: Daurian Shrike and Turkestan Shrike. Despite the fact that it breeds further east, Daurian Shrike is the more frequent (perhaps outnumbering Turkestan by 3:1). Surprisingly, there have been records from late February through to early December, but the peak is from mid September to late November. It is likely that Turkestan will prove to be an earlier autumn vagrant than Isabelline. About one-quarter of records have related to adult or adult-like birds (Slack 2009); oddly, this is a trend seen with other vagrant shrikes.

Taxonomy The taxonomy of the Isabelline Shrike complex seems to have been in a state of continual flux. Formerly regarded as conspecific with Red-backed Shrike, it was finally split from that species in 1980. In recent years there have been moves to split it further, into Turkestan Shrike (sometimes referred to as ‘Red-tailed Shrike’) which breeds in west-central Asia, and Daurian Shrike (sometimes confusingly referred to as ‘Isabelline Shrike’) which breeds further east in Mongolia and w. China. Panov (2009) explained that, as a result of their spatial separation and differences in the timing of their respective breeding periods, the two taxa do not normally interbreed in the Tien Shan Mountains, where their ranges come close. He recommended treating Turkestan Shrike as a monotypic species and Daurian Shrike as a polytypic species, containing the subspecies isabellinus, tsaidamensis and speculigerus. However, Pearson et al. (2012) demonstrated that the type specimens of isabellinus are compatible with populations breeding in Mongolia (i.e. speculigerus); thus speculigerus is a synonym of isabellinus and the name arenarius should be used for those breeders in the Tarim Basin. However, the two forms currently remain lumped by the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee, which has yet to accept isabellinus onto the British List. It must be stressed that the identification of the Isabelline Shrike taxa is far from straightforward, not least because hybrids are known to occur between the various forms, so a cautious approach is recommended. Inevitably, the following text cannot possibly cover all of the complications and subtleties, so anyone discovering one of these birds should endeavour to obtain good-quality images and consult detailed texts.

Plumage and structure Similar in size and structure to Red-backed, but the tail is marginally longer. Appears uniformly pallid with relatively little contrast between the upperparts and underparts. Most distinctive is a dark orange rump, uppertail-coverts and tail, suggesting a pale oversized female Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus. Its plumage shows soft buff, peach and orange tones, creating a warmer impression than Turkestan Shrike. Also, unlike that species, the sexes are similar. The primary projection is distinctly shorter than Red-backed Shrike’s, being about half to two-thirds the tertial length, rather than equal. Adult male Plain sandy grey-brown upperparts that are both paler and warmer in tone than Turkestan Shrike. The underparts are strongly washed with soft peachy-buff, becoming warm orangey-buff on the flanks (Turkestan Shrike is much whiter below). There is a strong black facial mask that does not normally extend over the forehead (the pattern of black across the lores is variable). It has a faintly paler supercilium, lacking the prominent white supercilium of male Turkestan Shrike, as well as its rufous coloration on the forehead and crown. Instead, the forehead, crown and ill-defined supercilium are strongly tinged warm peachy-orange. There is a small white patch at the base of the primaries. The bill has a pale pink or greyish base. Adult female Similar to male, but has pale lores, often a browner ear-covert patch and, sometimes, subdued scalloping on both the crown and the orangey-buff underparts. It may or may not show a white primary patch. The bill has a pinkish base. Juvenile/first-winter Unlike juvenile/first-winter Red-backed, the upperparts are uniform and unmarked, varying slightly from sandy grey-brown through pale fulvous-brown to pale cinnamon-buff. Little contrast with the underparts, which are pale whitish-buff (maybe with an orange wash to the flanks); some are slightly greyer below, others pale peach. Faint scalloping on the sides of the neck and breast, extending down the flanks, is the only patterning on the body plumage (with the possible exception of limited faint scalloping on the crown and back). The pale plumage contrasts strongly with the strikingly orange tail, uppertail-coverts and rump (variously dull orange, cinnamon-orange or reddish-orange); even the undertail is orange (greyish on almost all Red-backed). The head is less strongly patterned than Red-backed with the dark beady eye standing out. The forehead, lores and supercilium are rather pale buff, the ear-covert patch slightly richer (maybe with a slight rufous tinge but some, presumably males, have dark brown or quite blackish ear-coverts). Other points include: (1) a distinct pale wing-panel (pale tertial and inner secondary fringes); (2) lacks white patch at the base of the primaries; (3) paler-based bill (dark tip usually with a pink component to the base) and (4) blackish legs, which contrast with pale underparts (usually blue-grey on Red-backed).

Plumage Adult male Although superficially similar to Daurian, adult male is readily separable by its darker earth-brown mantle and scapulars (with a subtle greyish tint). These contrast with the crown, rump, uppertail-coverts and tail, which are strongly chestnut or reddish-tinged (tail slightly darker than Daurian). The upperparts show strong contrast with the silky-white underparts (sometimes tinged cream or orange-buff on the flanks). Like Daurian, it has a black face mask but, unlike that form, this may extend narrowly above the base of the bill, which is usually completely black (or slightly greyer at the base). Most importantly, the black mask contrasts with a very obvious white supercilium (often pure white). It too shows a white patch at the base of the primaries. Adult female Similar to Daurian but upperparts are darker, more earth-brown (subtly tinged greyish) and the tail is duller. Also, the white underparts (often tinged buff on the flanks) show obvious scaling. Like the male, the supercilium is whiter and more prominent (lores are also pale). Juvenile /first-winter Although similar to Daurian, less pallid, appearing somewhat intermediate between Daurian and Red-backed. The crown, nape, back and scapulars are a distinctly darker earth-brown, with a faint grey wash. It usually has a stronger head pattern, with a stronger whitish supercilium and darker ear-coverts, which may be distinctly chestnut-toned, the former scaled with black. Like Daurian, it has strong pale buff fringes to the greater coverts and tertials (perhaps with slightly more contrast between the fringes and the brown feather bases). Also like Daurian, it lacks a white patch at the base of primaries. The tail is less orange than Daurian, being a darker orange-red (more similar in tone to Common Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos than Common Redstart). The underparts are usually whiter (light buff when fresh) and scaled dark brown or black (maybe more so than Daurian). Unlike adult male, the bill base is pale pink. Like Daurian, the legs are black (usually blue-grey on Red-backed).

Separation from Red-backed The following should also be noted: (1) some Turkestan Shrikes approach less well-marked Red-backed in mantle colour and in the prominence of their underparts scaling; (2) a proportion of female and immature Red-backed show a decidedly rufous tail; (3) juvenile/first-winter Red-backed shows strong scalloping on the mantle and/or the scapulars and uppertail-coverts, whereas Turkestan Shrike is plainer (maybe some faint scallops remain); (4) adult female Red-backed is also plain above (but adults are unlikely to be seen in late autumn). If in doubt, both species can be aged by the fact that juveniles/first-winters have a blackish subterminal bar behind the pale tip of each greater covert, tertial and tail feather (much plainer on adult female).

Where and when Brown Shrike, which replaces Red-backed in Siberia, was first recorded in Britain in 1985, with a further 11 records in 2000–11. It was possibly overlooked in the past.

Structure Similar in size to Red-backed but structural differences are fundamental to its identification. It has a rather large head and, more importantly, a heavier bill, with a distinct upcurve to the lower mandible. Most significant, however, are the relative proportions of the wings and tail. The tail is distinctly long and the primaries short, creating an overall ‘short-winged/long-tailed’ structure that is somewhat reminiscent of a babbler (Timaliidae). Note in particular that the primary projection is only about one-third to two-thirds the length of the overlying tertials; this is in marked contrast to Red-backed Shrike which has long wings with the primaries and tertials equal in length (‘Isabelline’ Shrikes have the primary projection two-thirds to three-quarters the tertial length). The overall shape difference is further emphasised by the markedly long and narrow tail, appearing almost wagtail-like at times (the tail feathers are slightly narrower than Red-backed’s). Furthermore, its structure is different, being much more graduated, the outer feathers being only about half to two-thirds the length of the visible tail beyond the undertail-coverts (at least 80% on Red-backed and the ‘Isabellines’). It must be stressed, however, that the tail does not appear graduated in normal field views as the outer tail feather difference is usually obvious only when viewed from below; from above, the tail appears square-ended when closed.

Plumage Adult male Darker than the ‘Isabellines’, being plain russet-brown above, deep fulvous-buff below (throat whiter), with a black mask contrasting with a prominent pure white supercilum; the bill is black, often with a pink base. The tail is also russet-brown but the rump and uppertail-coverts are often more rufous. The race lucionensis, which breeds in China, has the crown and mantle more grey-brown (remarkably, an adult in Ireland in 1999 showed characters intermediate between this race and nominate cristatus; Slack 2009). Adult female Similar to male and sometimes indistinguishable, but the lores are sometimes paler, the mask slightly browner, the breast and flanks scalloped, and the bill base paler (BWP). Juvenile/first-winter As adult, the upperparts are russet-brown, usually plain, but some retain significant juvenile scalloping on the crown, back and scapulars. The rump and uppertail-coverts are more orangey-brown. The underparts are often strongly suffused with buff, but some are white with buff suffusion confined to the flanks. The breast and flanks are scalloped with brown. There is a diffuse whitish supercilium, a blackish patch through eye and pink on the bill base.

As with many closely related species, the identification of shrikes suffers from problems of hybridisation. There are several known hybrid zones in Asia, between Red-backed and Turkestan Shrikes and between Red-backed and Daurian (race isabellinus) while the odd hybrid may occur throughout the range of Turkestan Shrike (Lefranc & Worfolk 1997). One frequent ‘colour variety’ – known as ‘karelini’ – is thought to be a hybrid form between Turkestan and Red-backed, although this view is not universally accepted. Male ‘karelini’ have pale grey upperparts, but a rufous rump, uppertail-coverts and tail. Hybrids between Red-backed and Woodchat Shrikes have also been recorded in France, some of the offspring then back-crossing with pure Red-backed (Callahan 2012). In October 2008, a possible Brown × Red-backed Shrike was seen in the Isles of Scilly (Vinicombe 2009). As with all hybrids, there is no easy answer to their identification, but the possibility of hybridisation should be considered for any bird that ‘doesn’t look quite right’. The forensic analysis of good-quality photographs, or even a DNA sample, may be the only way of reaching anything approaching a firm conclusion.

Where and when A rare spring and autumn vagrant, most frequent in s. England. It currently averages 20 records a year, with a peak of 36 in 1997.

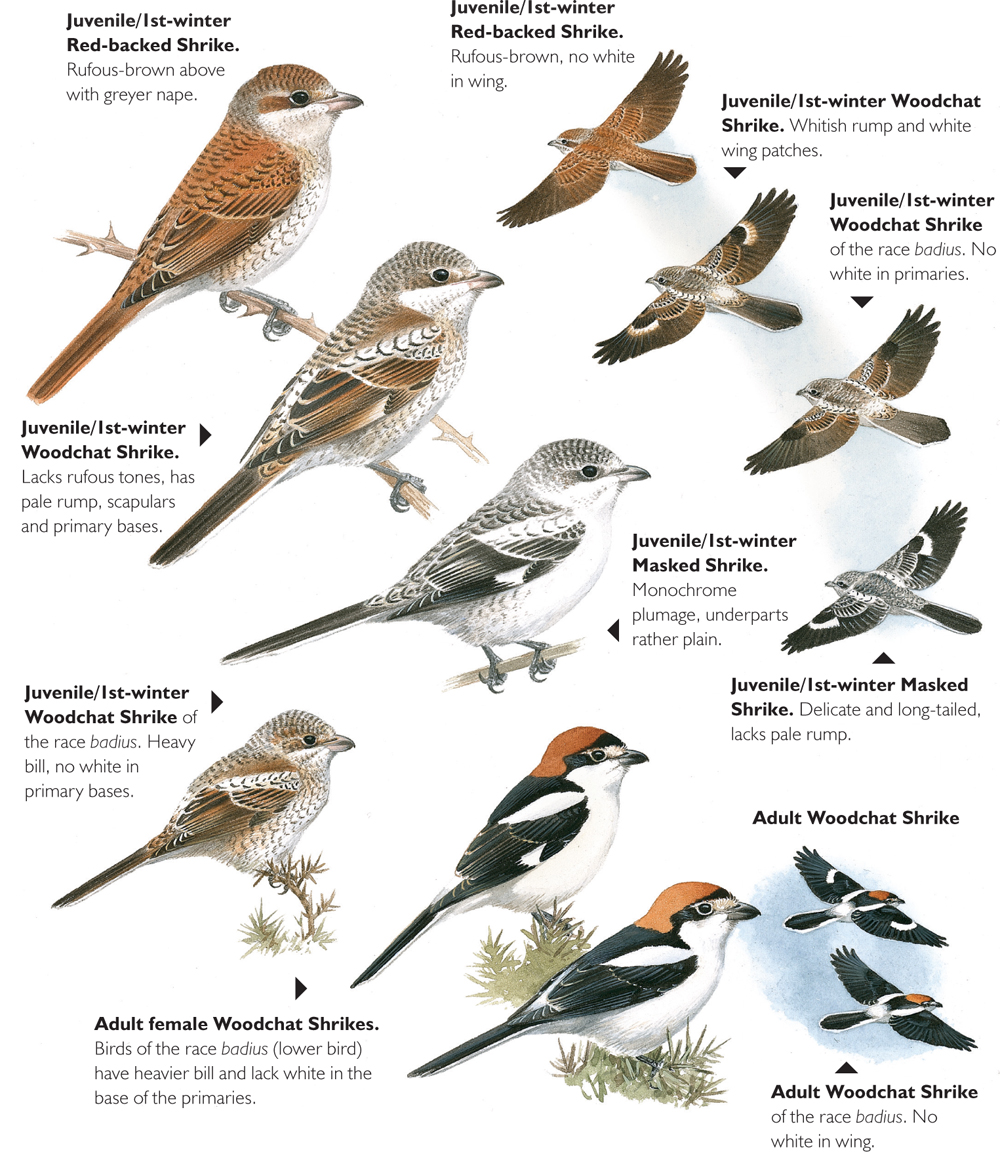

Plumage Adult Easily identified by its black-and-white plumage and chestnut rear crown. Females are duller than males, with a brown-grey tone to the mantle and a buffier forehead (but some first-summer males may be similar and are apparently impossible to sex). Juvenile/first-winter Young Woodchats retain much of their juvenile plumage throughout the autumn. Compared to Red-backed, they lack strong rufous tones and are messily scalloped on a colder, paler, buffy-grey background. Three features suggest their future adult patterning and are diagnostic: (1) a whitish rump; (2) whitish scapulars and median coverts; and (3) a buffy-white patch at the base of the primaries. All three characters vary individually and the whitish scapulars may not be as easy to see in the field as some guides suggest. Some autumn juveniles can show a faint rusty tint to the nape, again an indication of their future adult finery.

Balearic Woodchat

Woodchats that breed on the Balearic Islands, Corsica and Sardinia belong to the race badius (nine British records to 2010). Adults can be separated from the nominate by: (1) the lack of a white patch at the base of the primaries and (2) a distinctly heavier bill, with rather rounded upper and lower mandibles. Juveniles can be separated using the same criteria.

Eastern Woodchat Shrike

Another race of Woodchat – niloticus – occurs in the Middle East. Although unrecorded in Britain, first-winters have reached Sweden in autumn. The key difference is that, whereas nominate senator moults out of juvenile plumage in its winter quarters, juvenile niloticus moults mainly on the breeding grounds, prior to migrating. Thus, any autumn immature Woodchat showing extensive adult-like plumage could potentially be of this race. Occasionally, some nominate Woodchats also show limited post-juvenile moult, so such individuals should be photographed and expert advice sought; see Rowlands (2010) for more details.

Although there are only two British records (2004 and 2006) this species should be considered when faced with a late autumn juvenile Woodchat. Its plumage is superficially similar to Woodchat, with obvious white in the scapulars, but the key differences are: (1) distinctly greyer, described by Glass et al. (2006) as ‘cold, grey, white and black, lacking any warm or rufous tones’; (2) darker rump and uppertail-coverts; (3) large white triangular patch at the base of the primaries; (4) breast and belly mostly plain white, the scalloping confined mainly to the flanks. Just as important is structure: it is much more delicate than Woodchat, with a slim bill and a long, slender tail (perched on wires, it can look distinctly wagtail-like).

References Callahan (2012), Campbell (2012), Glass et al. (2006), Panov (2009), Pearson et al. (2012), Rowlands (2010), Slack (2009), Svensson et al. (2009), Vinicombe (2008).

Where and when Great Grey Shrike is a rare autumn and winter visitor, mainly from October to March, with numbers varying from one winter to the next. It currently averages 136 records a year, with a peak of 238 in 1998. It occurs in wild, open country such as moors, heaths and clearings in forestry plantations (although it may occur in surprisingly ‘ordinary’ farmland). Lesser Grey Shrike is a very rare and declining vagrant from s. and e. Europe (wintering in s. Africa); it averages just two records a year, with most in the Northern Isles and on the east coast. It occurs from May to November with most in late May/early June and September (any grey shrike seen in these peak periods should be carefully checked for Lesser). Steppe Grey Shrike is a very rare vagrant (24 records to 2011); it occurs from mid September to early December, with most in November (also single records in April and June/July). These have been widely scattered but with a basic pattern similar to Lesser Grey.

Structure Pay particular attention to the length of the exposed primaries beyond the tertials: on Great Grey, the primaries are short, appearing about two-thirds to three- quarters the length of the overlying tertials. Being a long-distance migrant, Lesser Grey has very long primaries, appearing perhaps 1¼–1½ times the tertial length (fresh- plumaged Lessers also show noticeable pale fringes and tips to the primaries). Other differences include Lesser Grey’s smaller size, thicker, stubbier bill and proportionately shorter tail (the latter perhaps explaining its tendency to adopt a more upright posture than its longer-tailed relative).

Plumage General features Note Lesser Grey’s lack of a white supercilium, its indistinct white scapular fringes and, in particular, its larger white patch at the base of the primaries. Both species have white in the outer tail: on Great Grey, this widens at the tip to produce white corners, whereas on Lesser Grey it broadens at the base to produce two basal tail patches (similar to male Red-backed Shrike L. collurio). Adults Adult Lesser Grey is easily distinguished from Great Grey by a broad area of black over the forecrown; this is extensive on males but may be slightly less extensive and less solid on females (or even absent). Fresh males have a beautiful soft, salmon-pink flush to the breast (greyer on females). Juveniles/first-winters Both species’ post-juvenile moult commences soon after fledging, so full juvenile plumage is unlikely to be seen in Britain; however, the moult is variable so some autumn migrants may retain at least some juvenile plumage (BWP). This shows fine barring and brownish plumage tones, and is most likely to persist on the crown and scapulars. Young Lesser Grey lacks the adult’s black forehead, so it could be easily passed off as a Great Grey. Concentrate on structural features, which apply to all ages.

Ageing All grey shrikes can be aged by reference to the greater coverts, which are all black on adults but duller black on first-winters, with buff or whitish tips (although good views are required to confirm this difference, especially as they wear towards spring).

Homeyeri Great Grey Shrike

This race occurs in a band from Bulgaria through Russia and into w. Siberia, immediately south of nominate excubitor. It has been claimed in Britain. It differs from the nominate in being paler, with a much larger white primary patch that in flight extends inwards across the bases of the secondaries towards the base of the wing. It also has more extensive white at the base of the tail.

Formerly treated as a race of Great Grey Shrike, this form is now lumped with the ‘Southern Grey Shrikes’ although, given that these birds are the subject of ongoing research, this arrangement may not persist.

Structure and plumage First-winter Similar to Great Grey Shrike but concentrate on the following. 1 PLUMAGE TONE Overall appearance very pallid: pale grey above and whitish below, sometimes with a pinkish-buff hue. Befitting a bird of arid environments, it has distinctly loose and rather fluffy plumage. 2 FACE PATTERN The key feature is the head. Whereas Great Grey has a black mask from the bill across the lores and back through the eye, first-winter Steppe Grey has a small oblong brownish-black patch behind the eye. This means that the lores are obviously pale and whitish. 3 BILL Note too that the bill base is also very pale whitish-grey (black on Great Grey, sometimes with a grey base). It is also heavier than Great Grey’s, with a stronger gonydeal angle. 4 PRIMARY PATCH Much larger and deeper white patch at the base of the outer primaries. 5 PRIMARY PROJECTION Distinctly longer than Great Grey’s with an obviously wider gap between the second and third visible primaries (counted back from the wing-tip). 6 TAMENESS Vagrants may be ridiculously tame: one in Lincolnshire in November 2008 perched on birders’ heads! Adult Black bill and a black eye-patch from the bill back through the eye, making the adult less distinctive than the first-winter (although females may show a grey tint in the lores). Identification therefore needs to be based on the other features outlined above.