Where and when Grey Wagtail is typically associated with upland streams, breeding throughout much of Britain and Ireland except across a large swathe of e. England from Humberside to Essex, where it is thin on the ground. More widespread in winter, when there is a general retreat from high ground, a southward withdrawal and some emigration (often appears in city centres at this season, where it may even breed). Yellow Wagtail is a summer visitor from late March to October, breeding mainly in England (generally absent from the south-west), e. Wales and s. Scotland (but virtually absent from Ireland); it has seriously declined in recent years. It occurs in marshy areas and on agricultural land, with a tendency to nest in pea fields. Several continental races also occur (see below) as well as Eastern Yellow Wagtails from e. Siberia (this group is now increasingly considered as a separate species). Citrine Wagtail is a rare vagrant with a few in spring (April–June) but most in autumn (mid August–October, with a peak in September). It has increased considerably since the mid 1990s, reflecting a westward spread into e. Europe; it currently averages 12 records a year (with as many as 21 in 2008).

Structure and plumage Easily identified: lively and restless with a very long tail (much longer than Yellow Wagtail’s) which is energetically wagged, particularly when alighting. Unlike Yellow, the head and mantle are grey (with a very slight green tint), it has a narrow white supercilium and yellowish green rump. On juveniles and winter females, the underparts vary from pale yellow to washed-out peachy-yellow, the only intense yellow being on the undertail-coverts. Males tend to be yellower on the breast and, in summer, have a black chin and throat (as can some summer females). The legs are pinkish or pale brown (blackish in Yellow).

In flight A slim, streamlined wagtail with a long, quivering tail and a broad white wing-bar.

Calls A loud, abrupt, penetrating, metallic tzip or tzizip, sometimes prolonged into an almost musical tiss-is-is-is-is-is. Generally rather solitary, frequenting streams, rivers, rocky shores, farmyards and rooftops; occasionally in grassy fields (but it does not habitually feed among cattle). They are strongly territorial with squabbling frequently occurring between close-feeding birds.

Structure and plumage A more evenly proportioned, shorter-tailed wagtail, green above and yellow below; habitually associates with cattle. Spring males are yellow and green on the head; females are duller green with a yellowish supercilium; all have a thin double white wing-bar and narrow white tertial fringes. Juveniles are duller and buffer (some, particularly females, being very colourless). They have a messy blackish lateral throat-stripe and blackish necklace on the lower throat (juvenile plumage is lost after the post-juvenile moult in late summer/early autumn, but migrants often retain traces of this plumage).

Call A very distinctive swee-up or sweep, useful when locating overhead migrants. Often occurs in small flocks and, in autumn, large numbers may roost in reedbeds.

Racial identification The racial complexity of Yellow Wagtails is notorious. Apart from spring males, most birders do not bother to racially identify them. Many of the extra limital races claimed in this country (e.g. Sykes’s Wagtail beema) may just be intergrades or local variations. Such birds may appear intermediate between Yellow and Blue-headed (often with lavender-coloured heads) and are often referred to as ‘Channel Wagtails’ as they tend to breed in coastal SE England, where the two races frequently come into contact. The following is a guide to the various head patterns (races listed in approximate order of frequency).

British Yellow Wagtail flavissima

Our native breeding form, male easily identified by its green-and-yellow head. Even females show strong yellow tones to the supercilium and throat.

Blue-headed Wagtail flava

The common form breeding on the near Continent. Males are greyish-blue on the head with a white supercilium and often a paler area in the centre of the ear-coverts (or ‘subocular patch’). Females can have slight bluish tones to the head and a whitish supercilium and throat, lacking the strong yellow tones of female flavissima.

Grey-headed Wagtail thunbergi

Breeds across n. Europe and n. Siberia. A rare late spring passage migrant on the east coast and very rare elsewhere. The male’s head is dark blue-grey with generally darker, blackish-grey lores. Most importantly, it lacks a supercilium, although some may show a narrow, faint, short one behind the eye. Some also show a necklace of dark spots on the upper breast. Females are not always safely separable from flava but they typically have a narrower, less clear-cut supercilum (sometimes lacking) and slightly darker and more ‘solid’ ear-coverts.

Black-headed Wagtail feldegg

This distinctive form breeds in SE Europe, Turkey and central Asia. Currently 17 late spring records (to 2011). In fresh plumage, males have a glossy black head that extends well down the nape to merge with the green upper mantle. The throat is yellow but in the easternmost part of the range a greater proportion show a white submoustachial stripe. Some males have a black head with a white supercilium; currently, such birds are not considered acceptable but there is uncertainty as to whether they are intergrades or pure first-summer male Black-headed. Females are often readily identifiable by their blackish heads, like washed-out males. Most show greyer upperparts and whiter underparts than other European races. Often has a more buzzy call: tzeeup. When identifying feldegg, great care is needed to eliminate grey-headed thunbergi, which can look dark-headed in certain lights.

Spanish Yellow Wagtail iberiae

Breeds in Iberia and NW Africa. Very similar to flava, but males have a large white throat that contrasts sharply with the bright yellow breast. In this respect it is similar to its close Mediterranean neighbour, Ashy-headed Wagtail cinereocapilla. Compared to flava, iberiae is slightly darker and greyer on the head, usually lacks a white eye-ring below the eye and a pale subocular patch. The supercilium is often lacking before the eye, but this is variable. Females are similar to female flava but tend to show a narrower, less distinct supercilium and lack a pale subocular patch; most significantly, they too show a large, contrasting pure white throat. Rather harsh call is similar to Black-headed.

Ashy-headed Wagtail cinereocapilla

Breeds in Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. Very similar to iberiae and may be best combined with it (call is also similar). Like that form, males have a large white throat, but most lack a supercilium or show just a faint narrow stripe above and behind the eye.

Sykes’s Wagtail beema

Breeds in Kazakhstan and SW Siberia. No longer on the British List; individuals resembling this form are much more likely to be intergrade ‘Channel Wagtails’ (see above). Genuine male beema is superficially similar to flava, but is slightly paler on the head with a longer and broader supercilium and whiter and more prominent subocular stripe, sometimes so obvious that most of the central ear-coverts look white. The upper throat and upper malar are also white (usually all-yellow in flava). Females resemble female flava but show a longer, broader and whiter supercilium, and more prominent subocular stripe.

Genetic research indicates that the e. Asian forms tschutschensis, macronyx and taivana may be best treated as a separate species ‘Eastern Yellow Wagtail’. As with other Far Eastern vagrants, birds resembling these forms occur in late autumn, mainly in the second half of October; some have remained to winter, with a penchant for sewage works. It remains to be seen, however, how the records will be treated by the relevant committees; currently, an analysis of their DNA is required. Birds resembling this form have a very consistent appearance, in many ways more reminiscent of first-winter Citrine. They are grey above and white below with a white supercilium, bordered above by a fairly thick dark grey lateral crown-stripe and below by a broad dark grey line across the lores; there is also a small but variable white subocular patch above a fairly discrete dark grey moustachial stripe. The white underparts show grey shading on the breast-sides and very faint streaking on the flanks. Whilst some calls may be similar to Yellow Wagtail, most distinctive is a slightly buzzy, more rasping spzzeu or zeup suggesting Citrine. A strange sibilant or slightly trilled spspsp was heard from one vagrant thought likely to be of this form. It also has a longer hindclaw (although there is overlap) and tends to show a stronger, slightly more dagger-like bill than Yellow, some with horn-coloured cutting edges and lower mandible. Note, however, that some European Yellow Wagtails are colourless grey-and-white birds, thereby clouding the issue. Any such bird seen outside the late autumn/winter occurrence period of Eastern Yellow Wagtail is far more likely to be an aberrant Yellow. See Collinson et al. (2013) for further information.

Structure and plumage Citrine is similar in shape to Yellow Wagtail, but slightly shorter-tailed; the bill may look longer and sturdier, and the head shape more angular. First-winter is grey above (slightly darker than White Wagtail M. alba alba) and whitish below, often with grey breast-sides, and some have a pale peachy tint to the breast. From behind, it resembles a White Wagtail, but from the front lacks White’s obvious black necklace across the upper breast. Later-moulting individuals may retain at least some browner juvenile feathering, particularly traces of the juvenile’s lateral throat-stripes and necklace, and should be aged as ‘juvenile/first-winter’. Conversely, some late autumn first-winters are strongly primrose-yellow on the head. On all birds, the white tips to the median and greater coverts, and the white tertial fringes are much broader than Yellow Wagtail and very striking. Pay particular attention to the head pattern, the following features being characteristic of Citrine. 1 A broad whitish supercilium (sometimes tinged yellow) extends right around the ear-coverts to form a complete ‘ear-covert surround’ (prominence varies individually and may be obscured if, for example, the head is sunk into the shoulders). 2 Usually a pale centre to the ear-coverts, often appearing as a broad pale crescent below the eye (‘subocular crescent’). 3 May also show a buff forehead (lacking on Yellow). 4 The supercilium may be emphasised by a narrow dark lateral crown-stripe.

Call Citrine has a very distinctive call: an almost buzzing dzzeeup, tzzeeeep or tzzweeeup, like a rasping Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis. Caution is needed, however, as some calls of Citrine are similar to Yellow and some races of Yellow Wagtail (e.g. Black-headed feldegg) and Eastern Yellow Wagtail, give ‘buzzing’ calls. Note that the latter appears mainly in late October, whereas Citrines appear from early August and peak in September. Eastern Yellows are similar to Citrine in their overall grey-and-white plumage tones, but they lack Citrine’s pale ear-covert surround. They have more solidly grey ear-coverts (at best only a narrow pale crescent below the eye) and narrower white wing-bars and tertial fringes; their structure is also more typical of Yellow Wagtail.

Spring birds Three races: adult male of the northerly nominate citreola has a pale yellow head and grey back, with a black collar; adult male of southerly werae is generally paler yellow, rarely has a black collar and little if any grey on the flanks; the even more southerly calcarata is darker yellow and has a black back. Spring males in Britain have resembled citreola. First-summer males tend to show messy black mottling on the crown and ear-coverts. Spring female is similar in pattern to first-winter (see above) but has bright yellow on the face and duller yellow underparts.

Where and when Pied Wagtail Motacilla alba yarrellii breeds commonly throughout Britain and Ireland; in winter, it withdraws from high ground and some emigrate. The Continental race alba (White Wagtail) is a passage migrant from early March to May and from mid August to October (a few linger into November in milder south-western areas). As most passage birds are en route to and from Iceland, they are commonest in western areas. It occasionally breeds in n. Scotland, sometimes intergrading with Pied.

Spring Plumage Adult male Pied is easily identified by its jet-black back and scapulars. Like both sexes of White Wagtail, female Pied’s mantle and scapulars are grey but they are darker than White’s, varying from blackish-grey, with black feathers admixed, to dark olive-grey; even greyer females look dark and sooty, with little contrast between the back and the head. Both sexes of White Wagtail have a pale, clean looking ash-grey mantle which, unlike Pied, contrasts strongly with the wings and the black-and-white head, producing a smart, clean-cut appearance. Like the back, the rump is pale grey, becoming darker grey towards the uppertail-coverts, which are blacker. On Pied, the rump is blackish or blackish-grey (but is often cloaked by the folded wings). Female Pied is quite a dark sooty-grey on the breast-sides and flanks but White has pale grey restricted largely to the breast-sides. In consequence, the flanks appear largely white, often with pale grey restricted to a narrow strip along the top of the flanks, immediately below the folded wing (the obviousness of this depends to some extent on how the wing is held). The predominantly white flanks are readily apparent in flight and this enables even migrating White Wagtails to be identified with some degree of confidence. Minor points include White’s duller, browner wings, while male White (because of its paler mantle and whiter flanks) may give the impression of having a larger bib. Sexing Spring adult White Wagtails can often be sexed by reference to the crown. In males, the black is clearly demarcated from the mantle, whereas on females it is less clear-cut, sometimes with grey admixed. On first-summer females (and some males) the black is reduced or even lacking, giving them a distinctive pale grey crown and nape.

Autumn Moult Although separating Pied and White Wagtails in spring is relatively straightforward, there is often confusion in autumn, when grey-backed juvenile Pied confuses the issue. However, there is a very simple short cut to the separation of the two forms at this time that renders the identification of White Wagtail straightforward. White Wagtails moult before they migrate, but the more resident Pied has a protracted moult throughout much of the autumn. Whereas Pied Wagtails commence their moult in mid July (on average), most do not complete it until the end of September or early October, taking on average 76 days to do so. White Wagtails, however, start their moult in early July but, because they need to moult before they migrate, they take just 46–48 days to complete it ( BWP). The upshot is that late August and September White Wagtails have already completed their moult and are in ‘clean’, immaculate and fresh winter plumage at a time when local Pieds are still moulting, appearing scruffy, ‘moth-eaten’ and dishevelled. As far as young birds are concerned, in late August and September, one is usually comparing immaculate first-winter Whites with scruffy, moulting Pieds that retain significant amounts of weak, fluffy juvenile body plumage. Plumage First-winter White has a pale grey crown and mantle, and a neat and contrasting narrow, crescent-shaped necklace on the lower throat/upper breast (broader and deeper on adults); this contrasts strongly with the almost all-white underparts. Not only are juvenile/first-winter Pieds scruffy at this time, but they still retain their black juvenile central breast-patches. In addition, autumn Pied is of course a darker, sootier grey on the upperparts (adult males are largely black above), but the important feature of autumn Pied (even after both species have completed their moult) is its extensive dark sooty-grey breast-sides and flanks.

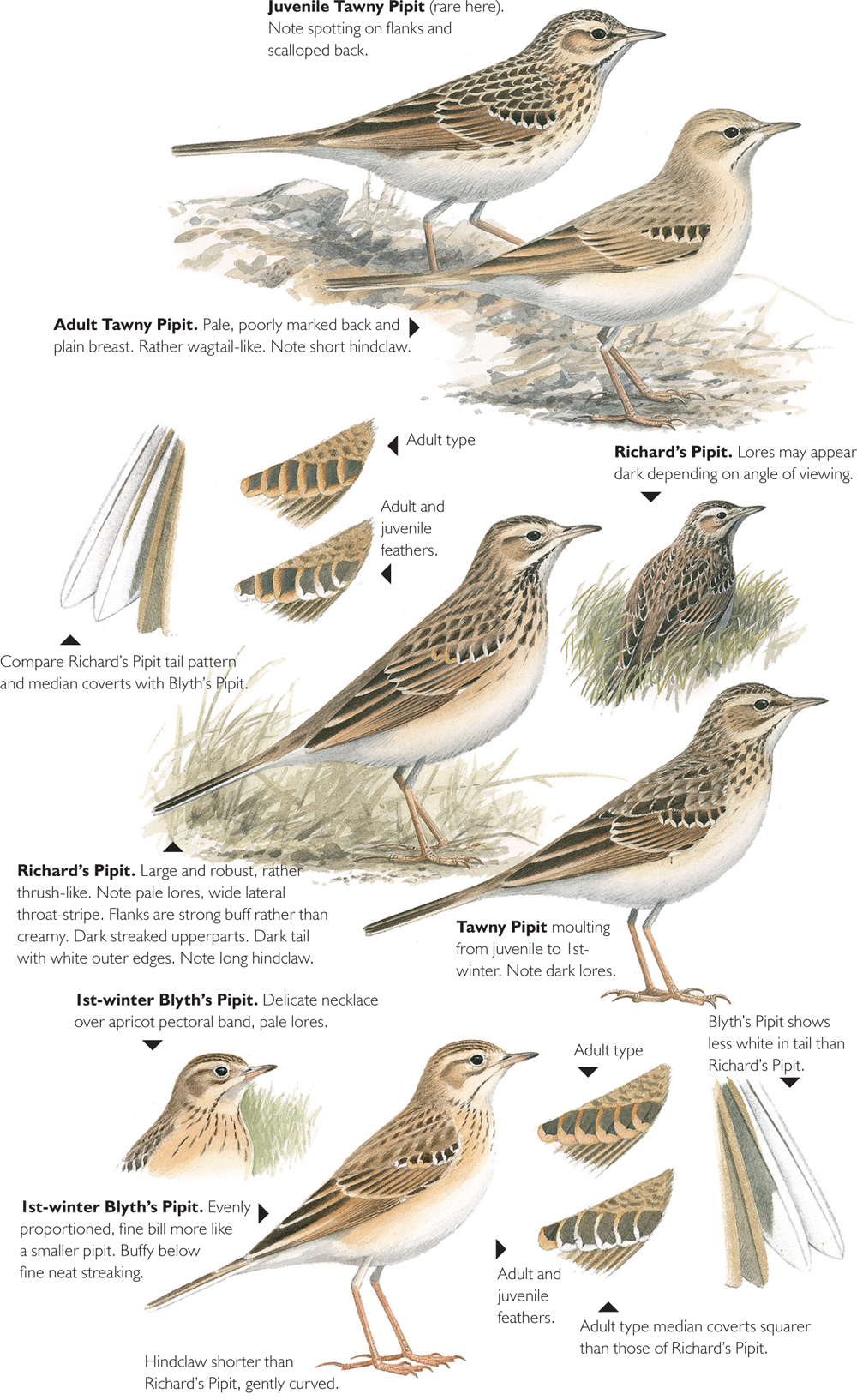

Where and when Tawny Pipit is a rare spring and autumn migrant, mainly in May and late August to September, with stragglers into October. Most occur on south and east coasts; it is rare in summer. Richard’s Pipit is a late autumn visitor from Siberia, seen mostly at well-watched coastal sites from mid September to November; some overwinter and there are occasional early spring records of wintering birds heading east. Therefore, any large pipit seen before mid September should be a Tawny, whereas, after early October, Richard’s is far more likely. Tawny currently averages just 11 records a year, having declined from an average of 36 in the 1980s, with a peak of 56 in 1983. This compares with a current average of 120 Richard’s, with a peak of 353 in 1994. Although Blyth’s Pipit was first recorded in 1882, the first modern record was in 1988. Since then, it has proved to be an increasingly regular late autumn vagrant between late October and early November, with a few staying into winter. There had been 22 records by 2011, most frequently in Shetland and Scilly.

Structure and behaviour Both are large, slim, rather wagtail-like pipits, with long, orangey legs; they feed with a start-stop action, sometimes wagging the tail (Tawny much more frequently). Whereas both are liable to be seen running on short grass, Richard’s tends to prefer longer grass, which Tawny avoids. Like Skylark Alauda arvensis, Richard’s may hover with a spread tail before alighting (Tawny rarely does this). Richard’s can appear almost thrush-like in its feeding behaviour. The flight of both is strong, undulating and rather wagtail-like.

Adult Tawny Pipit

Significantly smaller, slighter, less robust and somewhat slimmer-billed than Richard’s ( c.10% shorter and perhaps 20–30% lighter). Adult Tawny is easily separated by its pale sandy plumage, which lacks significant streaking. It has a whitish supercilium, narrow dark eye-stripe ( including the lores, which are pale on Richard’s), and narrow moustachial and lateral throat-stripes. Most significant is a black ‘bar’ on the median coverts, which contrasts strongly with the rest of the pale plumage (formed by large black centres to the feathers).

Richard’s Pipit

A rather bold, upright pipit, with a sturdy, deep-based, almost thrush-like bill that usually appears uptilted from the face. It has rather an ‘open face’, with pale lores, a dark eye-stripe behind the eye and a thin dark crescent-shaped moustachial stripe below the eye; however, the head is dominated by a broad creamy supercilium that extends around the back of the ear-coverts to form a complete ‘ear-covert surround’ (although note that some Richard’s have pale ear-coverts that render the ear-covert surround inconspicuous). The upperparts are well streaked, although in fresh plumage the streaking is subdued as broad brown feather fringes largely conceal the black feather centres. There are two buff wing-bars (wearing whiter) and broad buff tertial fringes. The underparts are creamy-white, often with warm orange-buff flanks. A narrow lateral throat-stripe expands into a large dark blotch at the base of the throat before merging into a gorget of fairly random brown streaks on the upper breast. In flight, it is large and rather long-tailed with a strong, undulating flight. When hovering prior to landing, it often spreads its tail to reveal extensive white in the two outer feathers.

Autumn moult of juvenile Tawny Pipit Identification problems in autumn relate to the fact that Tawny Pipits are often double-brooded; this means that late young may sometimes remain in the nest well into August. Consequently, later fledged juveniles do not have time to complete their post-juvenile body moult prior to autumn migration. They either suspend their moult during migration, or do not start it until arriving in their winter quarters. So, whereas first-brood Tawny Pipits have time to complete their moult and acquire adult-like first-winter plumage by late August, some second-brood birds do not reach this state until January. Because of this, young autumn Tawny Pipits are very variable: they are either in adult-like first-winter plumage, in full juvenile plumage, or various stages between the two. Paradoxically, it is the later occurring Tawny Pipits that tend to look the most juvenile.

Juvenile Tawny Pipit Richard’s (all ages) and juvenile Tawny can look surprisingly similar in superficial views. Concentrate on the head pattern, particularly the lores. Tawny has a distinct dark line between the bill and the eye, whereas, on Richard’s, the lores are plain and rather creamy, producing a rather pleasant, open-faced expression. Juvenile Tawny also has a stronger dark eye-stripe behind the eye, a better-defined dark moustachial stripe and lower border to the ear-coverts, all of which combine to produce a more ‘severe’ facial expression. Other differences are as follows. (1) On juvenile Tawny, the feathers that form the streaks on the mantle are finely fringed with white, so that the upperparts show lines of scallops, rather than solid streaks. However, these fringes wear as autumn progresses so that the scalloped effect is less obvious on later birds. (2) Juvenile Tawny usually lacks Richard’s large dark blotch at the base of the lateral throat-stripe, while the breast is delicately and profusely streaked, forming a deep gorget of fine and even streaking. Richard’s breast is more randomly and diffusely streaked. (3) Tawny’s slightly smaller size and more delicate structure mean that it can appear somewhat wagtail-like. (4) Tawny has a shorter hindclaw (7–12mm) whereas Richard’s is ridiculously long (13.5–19mm; Svensson 1992) best seen when perched on a wire fence.

First-winter Tawny Pipit As first-brood Tawny Pipits may have completed a late summer post-juvenile body moult by August, many first-winters are adult-like (pale, sandy and relatively unstreaked). Consequently, such birds are readily separable from Richard’s Pipit.

Ageing in autumn Regardless of variations in their body moult, both species can usually be aged by reference to their median coverts. Young birds usually show a mix of old juvenile feathers (black, narrowly and contrastingly fringed white) and new adult feathers (slightly longer, black and diffusely fringed buff).

Calls Superficially similar, but readily distinguishable with practice. Richard’s classic call is a loud, deep, rather explosive, sparrow-like chreep or chree-up. When excited, two or three calls may be run together. Conversely, it may sound softer, quieter and sometimes shorter and more clipped (although perception varies according to distance and the wind). These variations may lead to confusion, so do not expect a Richard’s to always give classic calls. Tawny’s call is also sparrow-like, but is softer, weaker and less rasping: chee-up, chlee-up or tree-up. Like Richard’s the call sometimes sounds more musical, a sparrow-like chlup or schlup while, conversely, it can sound like a harder trip.

Other pitfalls Richard’s and Tawny should not be confused with other species but mistakes have occurred. Occasional aberrant pale sandy-coloured Rock Pipits A. petrosus can suggest Tawny, as can summer-plumaged Water Pipits A. spinoletta (but the latter are likely to be seen only in late March/early April). Both species can be eliminated by their blackish legs and pseep calls, as well as habitat (rocky coasts and freshwater environments respectively). Tawny has also been confused with dull, buffy juvenile and first-winter Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava.

General Blyth’s Pipit shows few diagnostic features. Instead it exhibits a host of minor differences that create the impression of something distinctly ‘different’. The confusion species is Richard’s Pipit, but Tawny also must be considered, particularly those late autumn birds that retain significant juvenile body plumage (see above). Remember that the one key feature that separates Tawny from Richard’s and Blyth’s is the eye-stripe: on Tawny it extends from the bill across the lores and through the eye, whereas on Richard’s and Blyth’s it extends from the eye back, leaving the lores plain, pale and buffy.

Size and structure The plumage of Blyth’s is similar to Richard’s so it is size and structure that are likely to ring ‘alarm bells’. Blyth’s resembles a rather small, delicate Richard’s (in many ways more similar to Tawny in size and structure). Perhaps the most obvious initial structural difference is the bill, which appears distinctly smaller and slimmer than Richard’s. Nevertheless, it is quite deep-based and rather short, with a straight culmen and quite a pointed tip. It lacks the heavier, wedge-shaped, more thrush-like bill profile of Richard’s. The head too is rather small and it has a slender neck (frequently extended). All of this combines to form a daintier impression than the more robust Richard’s. Its relatively small size and slim appearance are also apparent in flight, when it looks slim and compact, lacking the bulky body and pot-bellied appearance often shown by Richard’s. In addition, it has a distinctly shorter tail, making it look more evenly proportioned than Richard’s, perhaps suggesting a large Tree Pipit A. trivialis. Some vagrants feed with flocks of Meadow Pipits A. pratensis and, in flight, they can be surprisingly difficult to pick out.

Plumage Basically similar to Richard’s but the following are the main differences. 1 PLUMAGE TONE Distinctly deep pale buff on the underparts (deepest on the flanks) perhaps similar in tone to autumn Whinchat Saxicola rubetra. The upperparts are well lined with broad blackish streaks. 2 HEAD PATTERN Subtly but distinctly different from Richard’s. The crown is regularly and evenly lined with black, lacking any hint of the dark lateral crown-stripes of Richard’s. The creamy supercilium is quite discrete, being confined to above and immediately behind the eye, and lacking Richard’s ‘ear-covert surround’. The lateral throat-stripe is much weaker and indistinct compared to most Richard’s, being fine and very narrow; most importantly, it ends in a small and rather faint patch (lacking Richard’s much more obvious dark neck blotch). 3 BREAST STREAKING Immediately below the lateral throat-stripes is a deep breast-band of profuse fine brown ‘pencil’ streaking, which reaches quite high on the breast and is deepest at the sides, narrowing in the middle. It is, therefore, distinctly different from the heavier, more random streaking shown by Richard’s. The streaking recalls the breast-band of a Skylark.

Calls Very important. Blyth’s gives several calls, all of them quiet and soft compared to the more familiar loud, rasping, sparrow-like call of Richard’s ( chreep or chree-up). Blyth’s utters a soft and squeaky schleup, a soft, abrupt schlup or tchlup, or quite an abrupt, soft, musical schleeu schleeu. These may be followed by a quiet but distinctive, subdued djup djup djup or a slightly musical skiew djup djup. At times, the djup calls may sound rather finch-like (recalling Linnet Linaria cannabina). An important point to bear in mind is that Richard’s sometimes gives softer or atypically abbreviated calls, so it is important to hear a series of calls before drawing firm conclusions.

Behaviour When feeding, Blyth’s has an energetic, nervous manner, often raising its neck so that it appears quite upright. Like Richard’s it often tilts its head to one side when feeding, looking at the ground in a thrush-like manner. It may feed with flocks of Meadow Pipits.

The ‘hard features’ Although, with practice, Blyth’s is a distinctive bird in its own right, three ‘hard features’ have traditionally been seen as fundamental to its identification and these should be checked if possible (good photographs will be helpful). 1 MEDIAN COVERTS In autumn, young Richard’s, Blyth’s and Tawny Pipits have varying combinations of juvenile and adult median coverts. The juvenile feathers are similar on all three species, being black with a clear-cut white fringe. The black centres are either pointed or rather rounded but with a slight point extending down the shaft. When present, the adult feathers are more diffusely fringed with buff, but the important difference is that, on Richard’s, the black centres of the adult feathers are pointed, whereas on Blyth’s they are more sharply defined and more squarely cut off (although often with a slight point down the shaft). When the adult median coverts are present, it is advisable to concentrate on the central feathers as these are the most consistently different (Heard 1995). 2 TAIL PATTERN Both species have extensive white on the outer-tail feathers, this being prominent in flight, but the pattern on the penultimate tail feather differs. On Richard’s, the white extends up the inner web in a long narrow point, immediately adjacent to the shaft, mirroring the pattern of the outer-tail feather. On Blyth’s, the white on the penultimate feather is broader, shorter, more restricted and more roundly or squarely cut off. Some Richard’s also show restricted white on the penultimate tail feather but it is still narrow and pointed, not appearing as a distinct broad patch, as it does on Blyth’s. 3 HINDCLAW Richard’s has a very long and fairly straight hindclaw, showing only a gentle curve. It is usually over 13mm in length and as long as 24.5mm on nominate richardi, which occurs in Britain . Blyth’s has a shorter and more arched claw that is 9–13.5mm long, and is thus more similar to the hindclaw of Tawny Pipit, which measures 7–12mm (Svensson 1992). The problem is that the hindclaw can be frustratingly difficult to see in the field (best seen if the bird lands on a wire fence).

Plumage variation Like Richard’s and Tawny Pipits, Blyth’s may vary in the extent of its post-juvenile moult. Some look very fresh, with broadly fringed upperparts feathering, showing broad pale feather fringes that severely reduce the streakiness of their upperparts. Conversely, unmoulted individuals can look darker, worn and streakier, while some rather dishevelled and ‘moth-eaten’ birds are likely to be in active moult from juvenile to first-winter plumage.

References Bradshaw (1994), Heard (1995), Svensson (1992).

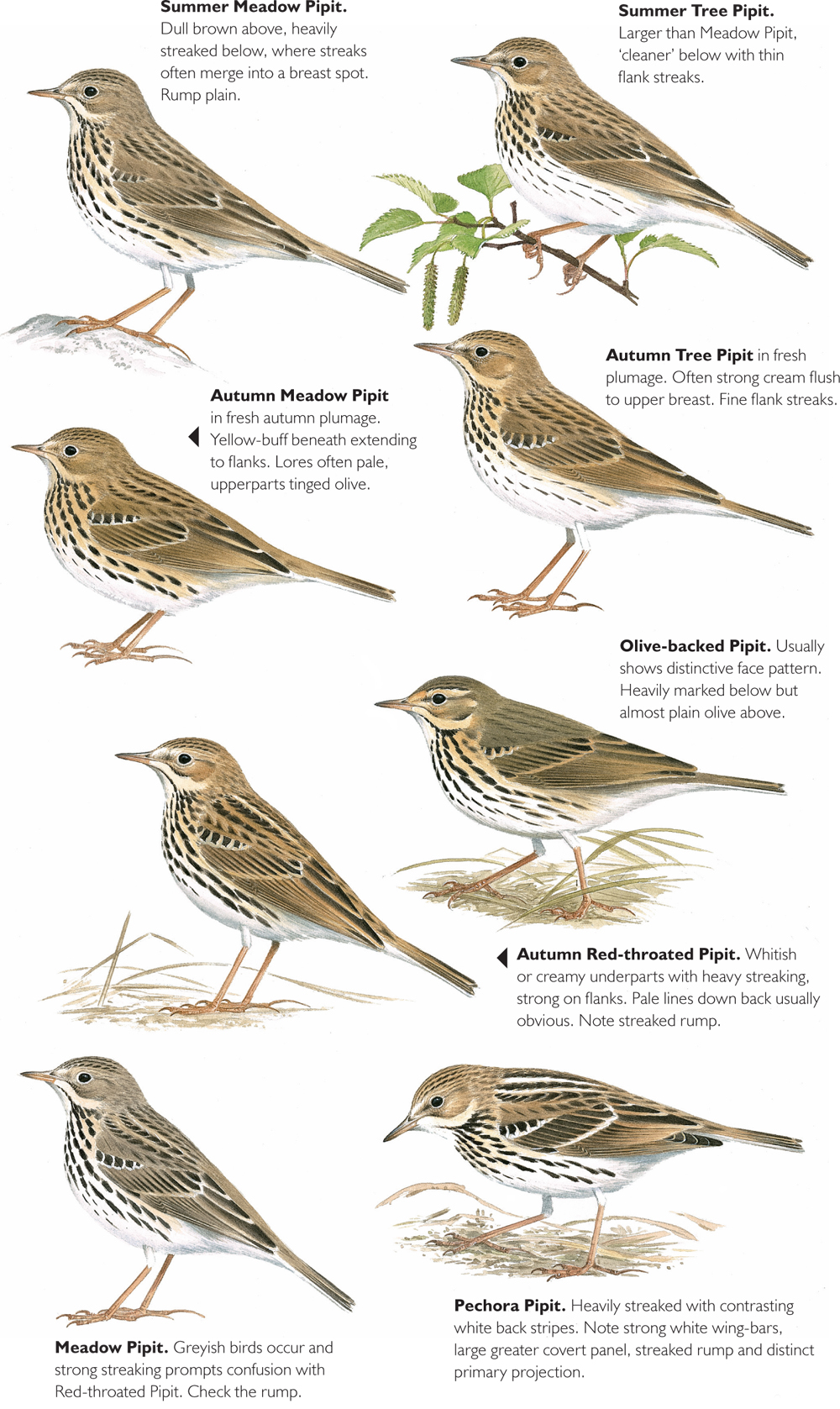

Where and when Meadow Pipit is an abundant breeding, passage and wintering species throughout much of Britain and Ireland. Tree Pipit is a summer visitor (mid April to October) breeding on heaths, woodland edges, young conifer plantations and rough ground with scattered trees. Most numerous in the north and west (but very rare in Ireland). Red-throated Pipit is a vagrant, currently averaging ten records a year, mainly in May and September/October (with as many as 47 in 1992). Olive-backed Pipit currently averages 13 records a year (with a remarkable influx of 43 in October 1990); it occurs mainly in late September and October, with a few into November; there have also been a few winter and spring records (the latter undoubtedly wintering birds en route back to Siberia). Both species are most frequently recorded at well-watched coastal sites, mainly on the Northern Isles and the British east coast. Formerly a great rarity, Pechora Pipit is now almost annual in late September and early October (with single spring and November records). It averages about three a year, with peaks of ten in 1994 and 2009. It occurs almost exclusively on the Northern Isles, with only the occasional record in the south.

These two species are similar, their separation being complicated by seasonal and individual variation in plumage tone. However, it becomes less difficult with practice, although many distinguishing features are subtle or inconsistent.

Calls The easiest distinction. Meadow has a familiar sip sip sip (number of notes varies, as does the power of delivery: sometimes sounding a lower-pitched and hoarser ski ski ski ski). Tree utters a short, incisive zeep, spzeep or a more scolding speez (overhead migrants are easily detected by this call); in flight, it can also give a very soft, barely audible sip. On the breeding grounds, both species utter a variety of calls: Meadow gives a dry si-sip or a soft, nervous sidip anxiety note, particularly when carrying food; Tree Pipit repeatedly utters a soft sit alarm call (also when carrying food) or a high-pitched, ringing stick (when the young are under threat).

Songs Meadow has a variable delivery, typically a rising sequence of chi-chi-chi-chi-chi… notes as it climbs in song flight, often accelerating into a trill before decelerating into a thin and more musical si-si-si-si-si... as the bird descends to the ground (Meadow’s song is similar to Rock Pipit’s A. petrosus, but the latter’s is typically ‘thicker’, slightly lower-pitched and simpler). Tree Pipit has a similar sequence but is louder and fuller, vaguely suggesting a Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs, and ending with a characteristic loud, far-carrying flourish: swee seee swee swee tu tu swee swee SEOO SEOO SEOO SEOO. This is frequently given in a parachuting display flight, often landing in the top of a tree. Particularly when singing from a perch, it may give an abbreviated version, lacking the final SEOO flourish: swee swee swee swee titititititit (the latter phrase a rapid trill).

Structure Subtle but definite differences. Tree Pipit is slightly larger, longer and sleeker-looking, with a longer, heftier and more wedge-shaped bill angled upwards from the face. Meadow is rounder-headed and less streamlined. Tree’s longer wings are readily apparent in flight, producing a slightly stronger, more purposeful flight than Meadow (which is weaker and more hesitant). The length of the hindclaw is diagnostic, but very difficult to see in the field: short and arched on Tree, very long and more gently curved on Meadow.

Behaviour Tree is far more arboreal than Meadow, often singing from the top of a tree, and it may walk along branches, wagging its tail. However, Meadow readily perches on or even in trees and bushes, particularly if flushed. When feeding, Meadow wanders rather aimlessly through vegetation, twitching its tail up and down, rather than gently wagging it; Tree is stealthier and more purposeful, although rather furtive.

Plumage Differences must be evaluated sensibly, bearing in mind that adults of both species show considerable wear by midsummer. In fresh autumn plumage, Meadow has a greenish tint to the upperparts and an olive-buff wash to the underparts. Spring adults are generally browner above and whiter below, showing few green tones; they are colder and more washed-out than autumn birds. Some particularly pale, stripy Meadow Pipits (probably of the race theresae from Iceland) pass through western areas in spring and autumn (potentially confusable with Red-throated Pipit; see Red-throated Pipit Anthus cervinus). In fresh plumage, Tree is better marked than Meadow, and the following differences are most useful. 1 FACIAL PATTERN Tree has, on average, a more strongly patterned face with a better-marked supercilium from the eye back and more prominent dark eye-stripe behind the eye (and often across the lores); it may also show a pale spot on the rear of the ear-coverts (often referred to as the ‘supercilium drop’). On Meadow, the supercilium and eye-stripe are more subdued and the lores are usually plain; this produces a markedly open-faced appearance in which the dark eye and pale eye-ring stand out. 2 THROAT AND BREAST COLOUR In fresh plumage, Tree has the submoustachial stripe, throat and breast strongly tinged orangey-buff, contrasting with the whitish belly. 3 BREAST AND FLANKS STREAKING The flanks streaking is perhaps the best and most consistent individual plumage difference. Tree’s streaking is confined mainly to the breast, with a gorget of neat, well-defined streaks, giving way on the flanks to faint pencil streaking that can be difficult to detect in the field. On Meadow, the breast streaking is more random, and the streaks often coalesce to form a dark spot in the central breast; unlike Tree, the streaking extends quite strongly onto the flanks. 4 UPPERPARTS Appear more contrasting on Tree: the wing-bars and tertial fringes are generally more prominent, and the dark-centred median coverts form a blackish bar (equivalent to the dark bar shown by Tawny Pipit A. campestris) often highlighted by contrasting white feather fringes. In summer, Meadow is noticeably colder, greyer, plainer and often ‘tattier’ than Tree Pipit, lacking strong greenish or buffy tones, but Tree Pipit also wears and fades by midsummer, becoming browner and plainer.

Call Most likely to be confused with a well-marked Meadow Pipit (see Meadow Anthus pratensis and Tree Pipits A. trivialis), but identification most easily confirmed by call, often the first indicator of a Red-throated amongst a flock of Meadow Pipits (records of non-calling individuals are likely to be very critically scrutinised by records committees). The flight call is a very distinctive thin, piercing, metallic psssst, trailing off towards the end. This may sound quite hoarse when flushed: skeez or skier. Chup calls are sometimes referred to in the literature but they appear to be given only when breeding.

Plumage Autumn Colder and less buff than Meadow, and much more heavily streaked. The lateral throat-stripe ends in a thick blotch on the neck-sides, joining heavy, broad breast striping; note in particular that this extends in two long thick lines down the flanks. The upperparts are strongly striped, with two pale ‘tramlines’ usually prominent on the sides of the mantle (more so than on many Meadow Pipits). The wings are also more strongly marked, the dark feather centres contrasting with buff or whitish fringes. Unlike Meadow and Tree Pipits, the rump is heavily streaked (usually best seen from the side when the tail is depressed while feeding). The bill is also stronger than Meadow, often with a yellow cutting edge and lower mandible. It looks distinctly shorter-tailed than Meadow, particularly in flight. Summer Easily identified by its brick-red ‘face’ and throat (note that autumn and winter adults, particularly males, may show at least a hint of this colouring, sometimes quite strongly). Spring migrants are usually in summer plumage (any retained winter feathers look worn, rather plain and dark, lacking the pale ‘tramlines‘).

Plumage Resembles Tree Pipit and, similarly, is often found in or around trees. Easily identified, the following being the most significant characters. 1 FACIAL PATTERN A prominent broad, creamy supercilium is highlighted by a thin black lateral crown-stripe and narrow dark eye-stripe, the whole effect vaguely recalling Redwing Turdus iliacus. A whitish spot on the rear ear-coverts (the ‘supercilium drop’) and dark lower rear border to the ear-coverts. 2 MANTLE On the race occurring in Britain and Ireland ( yunnanensis) the mantle has a distinct green tone and is only faintly streaked, at a distance appearing uniformly olive-green or, on duller individuals, olive-brown. 3 BREAST Can be quite buff or even orangey (often including the throat and submoustachial stripe) heavily streaked with thick black lines, extending more thinly onto the flanks. 4 TAIL-WAGGING Wags or ‘pumps’ its tail more persistently than Tree Pipit.

Call Basically similar to Tree Pipit’s but generally slightly shorter, thinner and shriller (with a slight Redwing-like quality), often with more of a consonant at the end and usually given doubly. Transcriptions include a thin speez, a shrill tzzseep…tzzseep; psee...psee; szip…szip or a thin, throaty ski or skier. High-flying individuals may sound more abrupt: ski…ski, similar to Tree but ‘throatier’.

Pitfalls Not difficult to identify, but note that some Tree Pipits also show a faint ‘supercilium drop’, while some are atypically plain on the mantle.

Plumage Like Red-throated, a well-marked pipit, but Pechora is surprisingly distinctive in its own right. An attractive bird, very clean and streaky. Like Red-throated, it has two mantle Vs but these are whiter and even more prominent. Two white wing-bars are broader, more prominent and squared-off to form two parallel ‘bands’ on the closed wing; it also has prominent white or warm buff tertial fringes. The underparts appear very white with neat black streaking forming a well-defined pectoral band, with two rows of heavy black streaks extending down the flanks. The crown is finely lined and it has a rather bland, open-looking face (often with a distinct ginger tone) in which the black eye and narrow white eye-ring stand out. The bill is mainly dull pinkish and the legs are also noticeably pale pink.

Structure Rather delicate with a proportionately small, somewhat rounded head and quite a long, fine and parallel-edged bill. Concentrate on the primaries: there is a distinct primary projection of two or three primary tips beyond the tertials (which completely cloak the primary tips in all other small pipits).

Behaviour and call Tends to be secretive and solitary, often flying a short distance before dropping back into cover. Vagrants invariably silent, but can give an unobtrusive, rather soft pwit or a sharp tswip.

Reference Mullarney (1987).

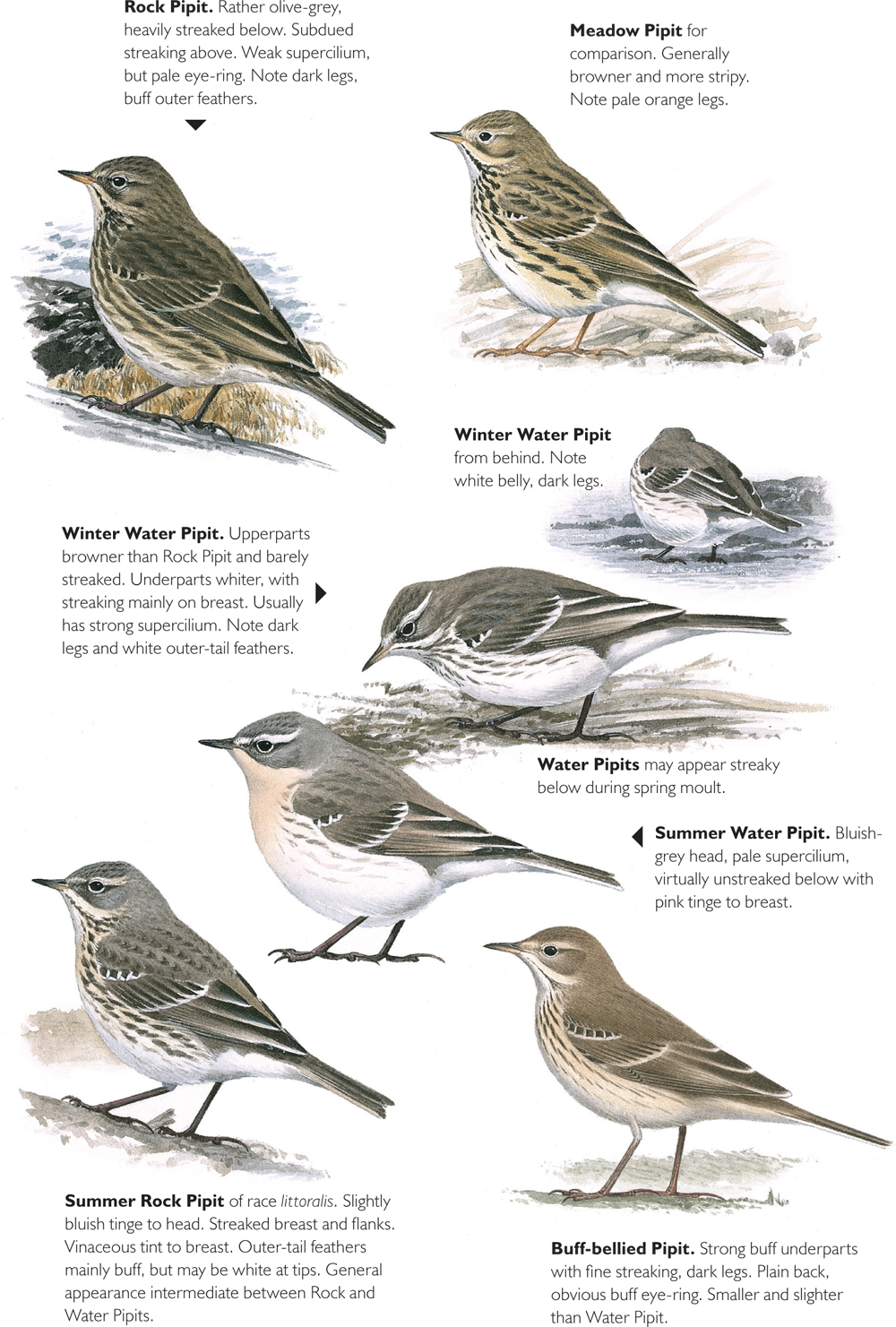

Where and when Rock Pipit is a familiar resident of rocky coastlines, although largely absent as a breeding bird from much of the English east coast between Lincolnshire and Kent. It frequents a variety of coastal environments in winter, when numbers are augmented by visitors of the Scandinavian race littoralis (which seem to occur mainly on coasts of e. and s. England). Rock Pipits also occur inland in small numbers, mainly from September to November and again in March, but also occasionally between times. British Water Pipits originate from the mountains of s. Europe and are widespread but local from mid October to mid April, mainly in s. England. They occur in a variety of freshwater habitats, such as reservoirs, sewage farms, cress beds and marshes, but they generally avoid saline environments (although they may resort to coastal marshes in freezing weather). Water Pipits seen in saltwater environments should be identified with caution. Highest numbers occur during mild winters, and hard winters may severely deplete their population. Buff-bellied Pipit is a North American vagrant, increasingly identified mainly in western areas (27 records to 2011).

Habitat and behaviour In many ways rather nondescript, but easily identified in typical habitat: rocky coastlines. Although rarely found far from the inter-tidal zone, wintering or passage individuals may occur in less typical surroundings, such as inland lakes and sewage farms. Here they invariably select an area most akin to their usual habitat, such as a reservoir dam or a stony shoreline. Usually rather solitary and, unlike Water Pipit, often relatively tame.

Size and structure Compared to Meadow Pipit A. pratensis, Rock is a larger, bulkier, more upright bird with longer legs and a noticeably longer, more dagger-like bill (all dark or with an extensive orange lower mandible). In flight, longer-winged and longer-tailed, with a more purposeful flight action than the weaker, rather more hesitant Meadow Pipit.

Plumage Heavily colour saturated, producing a dark and oily appearance that blends in with its rocky surroundings. Its smoky-olive upperparts are darker than Meadow Pipit’s and relatively unstreaked; the wings show two dull creamy-buff wing-bars. The underparts are rather dull yellowy-cream, with heavy brown streaking covering not only the breast and flanks but also much of the belly. It has a relatively plain face with a narrow creamy eye-ring (usually broken) that is typically more obvious than the subdued creamy supercilium (often indistinct). Two further features eliminate Meadow Pipit: the legs are dark, blackish at long range but dark pinkish-red close-up (bright pinkish-orange on Meadow), and the outer-tail feathers are creamy or pale brown (white on Meadow). In summer, Rock Pipits often become worn, appearing greyer above and whiter below, with a contrastingly black bill and legs; in such plumage, these individuals may suggest Scandinavian littoralis (see Scandinavian Rock Pipit Anthus petrosus littoralis). Juvenile Recent fledglings may have pale pink legs and extensive pink or orange on the bill, as well as broad, buff wing-bars.

Call A single, loud, shrill pseep or feest. Meadow Pipits usually give a thinner, weaker sip sip sip and, although single calls are not infrequent, the difference in quality is distinctive once learnt.

Song Similar to Meadow Pipit but slightly slower, throatier and simpler.

Habitat and behaviour From damp freshwater habitat a large, timid, streamlined pipit flushes at some distance and rises high into the air, giving a loud, shrill, strident fsst: as it gains height, it swings back behind the observer and drops into similar habitat several hundred metres away; its flight is strong and direct, it is longer-winged and longer-tailed than a Meadow Pipit, and its underparts look contrastingly pale as it shoots overhead. Such is a typical encounter with a Water Pipit. Rock Pipit is usually quite tame and, in similar circumstances would have probably flushed at close range, flown low over the water and resettled after a relatively short distance. Although such behavioural differences are not diagnostic, this is one that invariably holds true. Rock Pipits are also strongly territorial and have a bold demeanour, perching prominently on rocks and boulders, calling loudly and indulging in frequent territorial chases. Water Pipits, in contrast, are much more sociable and sometimes occur in small parties, often with Meadow Pipits. In spring, they may feed in fields and, unlike Rock, readily perch in trees and bushes. In the evening, they may roost communally in reedbeds.

Plumage Winter Seen well, Water is smarter and more contrasting, browner above and whiter below, with streaking largely confined to the breast (weaker on the flanks). What usually attracts attention is the whitish supercilium, which typically extends from the bill, over the eye, and tapers towards the nape. Note, however, that this feature varies, some being less well endowed than others, while a small minority shows virtually none at all. The wing-bars, tertial fringes and outer-tail feathers are much whiter than in Rock (not creamy or brownish). In winter, the bill usually has a yellow base to the lower mandible. Summer Unlike British Rock Pipits (race petrosus), Water Pipit acquires a distinct summer plumage. A body moult occurs from late February to early April and, consequently, birds at this time are often scruffy and dishevelled. However, they leave Britain in full summer plumage, which is quite striking and very attractive, almost wagtail-like, comprising a pale blue-grey head (the white supercilium is retained) and off-white underparts that are virtually plain, with a beautiful pale pink or soft apricot flush to the breast (some streaking may persist on the breast and flanks).

Call Very similar to Rock Pipit’s pseep but Water Pipit’s is perceptibly thinner and weaker: more of a fssst. Remember that Water’s calls are given singly (although Meadow also give occasional single calls).

Unlike British birds, which are similar year-round, Scandinavian Rock Pipits (race littoralis) acquire a distinct summer plumage that enables them to be distinguished with some certainty before they depart in spring. There appears, however, to be something of a cline between Rock Pipits in n. Britain and those in s. Scandinavia, as well as individual variation, so not all will be certainly identifiable. ‘Classic’ examples acquire certain plumage characters in spring ordinarily associated with Water Pipit, so a potential Water Pipit in atypical rocky or stony habitat, or outside the normal range, should be carefully checked to eliminate littoralis Rock Pipit. The latter has a blue-grey tone to the head and rump, a distinctive creamy-white eye-ring and supercilium (at least from the eye back) and rather whitish wing-bars; the underparts acquire a strong creamy-buff, yellowish or salmon-pink suffusion (off-white, suffused pink, on Water Pipit). However, unlike Water, this is overlain with variable brown streaking on the breast and flanks; they also retain their dark lateral throat-stripe. Some, however, are virtually plain on the breast, so great care is needed. Unlike Water Pipit, littoralis Rock has creamy or pale brown outer-tail feathers, although on some the outermost tail feather is whiter towards the tip.

Most likely to be found with flocks of Meadow Pipits in drier habitats than Rock and Water Pipits (often in fields). Slightly smaller and less sturdy than Rock and Water, with a more rounded head and weaker bill. Entire plumage strongly suffused buff. It has a fairly plain back and scapulars but buff wing-bars and tertial fringes, and brown streaking on its strongly buff underparts. The head is relatively plain with a weak buff supercilium and pale lores; most distinctive is an obvious buff eye-ring. Like Water Pipit, it has dark legs. Summer adults are a soft grey on the head and upperparts with an apricot supercilium and underparts, the latter with delicate upper breast streaking. Its soft calls are reminiscent of Meadow Pipit, but are usually fast, urgent and distinctly two-, three- or four-noted: si-sip, si-si-sip or si-si-si-sip.

References Johnson (1970), Knox (1988), Williamson (1965).