R. Marston Speight

The following is a form analysis of the tradition attributed to the sons and daughter of Sa'd b. a. Waqqāṣ according to which their father was forbidden by the Prophet to bequeath more than one-third of his estate. This ḥadīth became one of the fundamental texts of Islamic laws of succession. The analysis is based on principles and presuppositions which have been enunciated in an unpublished doctoral thesis.1) The results of this study are in no wise conclusive or satisfying in themselves. They constitute but some of the elements which go into a full comprehension of the ḥadīth literature. The limitations of this kind of inquiry point out the need for team work in the field. Legal specialists, historians of religion, isnād critics, linguists and others should coordinate their efforts and concentrate their insights upon a particular body of texts.

One can scarcely speak of the laws of form analysis in the field of oral literature. Too many elements are missing in the evidence at our disposal for definitive statements to be made. But use can be made of observations made by students of other oral literatures, and above all one can "listen" to the texts, making an effort to appreciate their quality as orally transmitted material. What we have as evidence are nineteen versions, each one in a stage of suspended development, suspended from the moment that it became frozen in a written compilation. Because of better attestation and usefulness, some versions were "performed" and passed on far more often than others. This fact is reflected in the higher degree of evolution which they manifest. However, they coexist with less known and less well attested versions which by virtue of their more limited use show a less full evolution. It will be noted that no effort is made here to analyze the asānīd. This is not because they are considered to be unimportant, but simply because a form analysis must be concerned primarily with the structure of the main. A few obvious and significant features of certain asānīd will be pointed out, however.

The nineteen versions will be presented in the order of their complexity.

M. b. 'Umnar, Sufyān b. 'Uyayna, I. a. Najīḥ, Mujāhid.

Sa*d b. a'. Waqqāṣ said: "I fell ill, and the Apoatle of God came to visit me. He put his hand on my breast and I felt its freshness on my heart. Then he said, 'Something is wrong with your heart. Call for al-Ḥārith b. Kalada, a member of the Thaqīf tribe, for he is a physician. Tell him to take seven 'Ajwa dates from al-Madīna, crush them along with their pits and then put them into the corner of your mouth.'"2)

The form of this text is that of a biographical detail from the life of a Companion. It is one of the more developed of the reportorial types to be found in the ḥadīth literature. However, it did not evolve into a story form. Also the absence of description and the conciseness of the text point to a less than full evolution. On the other hand there is evidence of a certain amount of change from a hypothetical primitive version. This is seen in the use of the first person and the direct quotation from the Prophet. The latter would sound more natural as indirect speech. On the whole, however, this text is remarkably unified and coherent. It bears the marks of an authentic and spontaneous recollection, whose life setting should not be sought in other than biographical interest.

Certain elements of the text recur in other ḥadīth, as, for example, the visit by the Prophet to a sick friend, the laying of his hand upon the sick one's breast, and the medicinal value of 'Ajwa dates.3) But these motifs help to form a harmonious whole here, whereas we feel that when they are used elsewhere, they are drawn in to serve other life settings in a slightly artificial way.

This text apparently only occurs in I.S and A.D. It was probably not used extensively, perhaps because it served no legal or religious purpose.

It is distinctive in that it is one of the very few versions that is not attributed to a child of Sa'd, This distinction could be significant if a full study of the nineteen asānīd should reveal that attribution of a version to a child of Sa'd was more than likely only a formal device used by subsequent guarantors.

Archaic words found in this text are: waja'a, "to crush, to pulverize", and ladda, "to put a medicine in the corner of a patient's mouth."

2. Yaḥhyā al-Qaṭṭān, al-Ja'd b. Aws, 'Ā'isha bint Sa'd.

Sa'd said: "I became ill in Mecca, and the Apostle of God came in to visit me. He rubbed my face, my chest and my abdomen. Then he said, 'O God, heal Sa'd.' And in my imagination I can still feel how cool his hand was upon my heart."4)

This, another biographical detail, is clearly related to 1., but it has changed considerably. The place given is Mecca. The Prophet's rubbing of Sa'd's body is not said to be for the purpose of diagnosis, as the touch was in 1. Elaboration is seen in the increase of the number of places on the body which he touched, the fact that he rubbed Sa'd's body, and the abiding recollection of the coolness of Muhammad's hand. The prayer for healing is a new element, and because of evidence to be seen in subsequent versions, we feel that it is probably drawn from a tradition about another individual. We can imagine that the two stories became confounded, perhaps because Sa'd's renown was so much greater than that of the other person.

Without any other evidence the life setting appears to be similar to that of 1., but the story has lost its unity of structure. We shall see however, upon examination of 3., that it and 2., probably had the same life setting.

3. Hārūn b. "Abd Allah, Makkī b. Ibrāhīm, al-Ja'īd, 'A'isha bint Sa'd.

Her father said: "I became ill in Mecca, and the Prophet came to visit me. He put his hand upon my brow, then he rubbed my chest and my abdomen. Then he aaid, 'O God, heal Sa'd, and make his emigration oompletel'"5)

2. and 3. represent what we might call a vertical development of the tradition, that is, the evidence of minor differences within a group of versions having the same general structure and content. By contrast there will be seen a horizontal development also, in which new elements are combined or old ones reshaped to appear in different structures and with varying content. In 3. the recollection of the Prophet's hand is omitted, and a new element is added, which explains the fact that the incident is localized in Mecca.

The life setting here is the concern for building up the new Islamic community in Medina, composed in large part of muhājirūn, or emigrants from Mecca and other localities. There was a concern that those who emigrated to Medina should stay there.6)

Because Mecca is mentioned in 2. as well as in 3. and because the primary guarantors are the same in these two texts, we believe that they are essentially the same. Each of them omits an element, either from forgetfulness or from misunderstanding; but the omission in 2. is more serious than in 3., since it obscures the main point of the recollection,

The incident reported regarding the emigration was not expanded, because its purpose had been seved after the death of the Prophet and the beginning of the spread of Islam.

4. M. b. 'Umar, M. b. Ṣāliḥ, 'Asim b. 'Umar b. Qatāda.

And Sa'd b. Khawla took part in the Battle of Back- when he was twenty-five years old. He also took part in 'Uḥud, al-Khandaq and al-Ḥudaybīya. He married Subī'a bint al-Ḥārith al-Aslamīya, who, a little while after he died, gave birth to a child. The Apostle of God said to her, "Marry whom you will."

Sa'd b. Khawla had gone forth to Mecca and died there.

In the year of the Conquest of Mecca Sa'd b. a. Waqqāṣ became ill and the Apostle of God came to visit him, when he came from al-Ji'rānā to visit the holy places. He said, "O God, complete the emigrations of my Companions, and do not send them back to where they came from."

But the unfortunate one was Sa'd b. Khawla. The Apostle of God lamented him. He disliked that anyone who had emigrated from Mecca should return to it, or remain in it more than was necessary to accomplish his pious exercises.7)

Here the story of Muhammad s visit to Sa'd is introduced abruptly, without even an isnād, in connection with the biographical detail about Sa'd b. Khawla. The life setting is still the same as 2. and 3., that is, a concern for maintaining the integrity of the group of muhā-jirun in Medina. To reinforce the importance of completing the hijra, Sa'd b. Khawla is placed in the story as a foil to Sad'b. a. Waqqāṣ.

The manner in which the comment about Sa'd b. Khawla is appended to the account of the sick visit shows that it was an afterthought. It is not clear whether the Prophet was supposed to have said that Sa'd was the unfortunate one, or whether it was a comment by the guarantor.8) At any rate this comment became an integral, although disjointed, part of the tradition, as will be seen in further versions.

Sa'd s wife, Subī'a, was said to have added still more force to the point about the hijra by reporting that Muhammad said, "Whoever is able to die in Medina (understood, as an emigrant), let him die there. Whoever dies there will benefit from my intercession or my testimony on the Day of Resurrection."9)

The detail that Sa'd fell ill during the Conquest of Mecca may have been added to make the date to coincide with the time when some authorities, although a minority,10) thought that Sa'd b. Khawla died. The stronger opinion was that he died later, at the time of Muhammad's Farewell Pilgrimage, and we shall see later how this affected the development of our tradition.

Version 4. with its awkward juxtaposition of elements from two biographies, and the use of the third person in the narration' was probably not a much used version. On the other hand, the direct quotations from the Prophet and the statement, "Do not send them back to where they came from," not seen in 2. and 3., reveal a certain amount of creative evolution.

The next five versions are all based on the recollection that Muhammad visited Sa'd when he was ill. But the relationship to 1. is only implicit. There is no explicit link, and an entirely new element is added. This horizontal development of the tradition can be seen in two vertical trends.

Trend I

5. 'Abd Allāh, Ibn Hanbal, M. b. Ja'far, Shu'ba, Simak, Mu§'ab b. Sa*d, Sa'd. The Apostle of God went in to visit Sa'd when he was ill. He said, "0 Apostle of God, shall I bequeath all of my wealth?"

M.: "No."

S.: "Two-thirds, then?"

M.: "No."

S.: "One-third, then?"

And he was silent.11)

6. Zuhayr b. Ḥarb, al-Ḥasan b. Mūsā, Zuhayr, Simāk b. Ḥarb, Muij'ab b. Sa'd, Sa'd.

S.: "I fell ill, and I sent for the Prophet. Then I said to him, 'Let me divide my wealth as I please.' He refused. Then I said, 'A half, then?' He refused. So I said, 'A third, then?' After the third he was silent."

He said, "And afterwards the third was permitted." 12)

The new element is introduced by a stereotyped Statement, Question and Answer form. 5. occurs within a larger structure which is a collection of anecdotes regarding Sa'd, several of which have to do with the reasons for the revelation of certain Quranic verses. It would appear to be a quite undeveloped version of the legal text which, as it received increasing use through other chains, evolved in the direction of greater legal precision. 5. is loosely strung along with miscellaneous unrelated accounts; it is told in the third person; no place is indicated; no motive for the question is given; and Muhammad's last answer of silence is vague, although it implies grudging approval.

6., also from Simak and Mus'ab, is told in the first person and includes a slight amount of elaboration. It is isolated from the miscellaneous collection in which 5. is found. The final statement of commentary is from an unknown guarantor. It is unlikely that Sacd is represented as the speaker of these words.

The life setting of this text is not clear. Joseph Schacht proposed that the legal principle involved was a measure taken by the Umayyad administration to assure that the state might receive a generous portion of the estate of those who left no heirs.13) Be this as it may, from the standpoint of literary structure, it seems fairly clear, as subsequent versions will bear out, that the Statement, Question and Answer about Sa'd's will is a form in search of a natural setting. It is unnatural to think of it as belonging to the kind of original situation which we see in 1. Without going so far as to say that the text was a pure invention of second century jurists, we sense that its circumstantial setting is of strictly secondary importance. These versions express only a single, unadorned legal principle in a stereotyped formal structure. And yet, the memory of Muhammad's visit to Sa'd (I.), as well as his concern for the Companions' hijra all play upon the transmitters' minds, so that they seek, at least in some chains, to make a combination of these and still other elements, together with the testament question. The nature of this amalgam of elements will shed further light upon the tradition's history.

Trend II

7. 'Abd Allāh, Ibn Ḥanbal, Wakī', Hisham, his father, Sa'd. The Prophet went in to visit him when he was ill. He said: "0 Apostle of God, shall I bequeath all my wealth?"

M.: "No."

S.: "A half, then?"

M.: "No."

8.; "A third, then?"

M.: "A third, and a third is a lot, (or) a large portion."1*)

8. al-Qāsim b. Zakarīyā', Ḥusayn b. 'Alī, Zayda, 'Abd al-Malik b. 'Umar, Muij'ab b. Sa'd, his father.

He said, "The Prophet visited me and I said, 'Shall I bequeath all my wealth?'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'A half, then?'

M.: 'No.'

8.: 'What about a third?'

M.: "Yes, and a third is a lot.'"

9. 'Abd Allah, Ibn Hanbal, 'Abd al-Rahman, Hammam, Qatāda, Yunus b. Jubayr, M. b. Sa'd (May God be pleased with him), his father.

The Prophet went in to him when he was sick in Mecca.

S.: "I have only one daughter; shall I bequeath all my wealth?"

M.: "No."

S.: "Shall I bequeath a half?"

M.: "No."

S.: "Shall I bequeath a third?"

M.: "A third and a third is a large portion.' '15)

Although these three versions have different chains of guarantors, they seem to belong to one vertical development. All three of them have Sa'd ask, "Shall I bequeath all my wealth?" All three have the detail of Muhammad's qualified approval of one third, thus bringing more precision to the rule than was seen in 5. and 6. 8. is probably at a later stage of development than 7., since it is in the first person. The omission of mention of Sa'd's illness in 8. is insignificant, since the verb, 'dcla means "to visit a sick person." 9. shows a still greater evolution with the addition of a motive for the question: "I have only one daughter," but it is not clear whether this means that the daughter was his only family relation, his only descendant, or his only heir.

Early in the history of the transmission of our tradition the two horizontal developments that we have noted (2., 3. and 4. on the one hand, and 6., 6., 7., 8. and 9. on the other) joined in varying ways. The recollection of 1. recurs in fragmentary fashion, and serves as an unsuccessful means of integrating the various elements which are combined into complex, but disjointed texts. Calling this effort at combination a third horizontal development, we note within it two vertical movements, based on the main point of the text. In one case the Companions' hijra is slightly uppermost, whereas in the other, Sa'd's will is obviously primary.

I. Hijra texts

10.'Abd Allah, Ibn Ḥanbal, 'Abd al-Rahmān, Sufyān, Sa'd, 'Āmir b. Sa'd, his father.

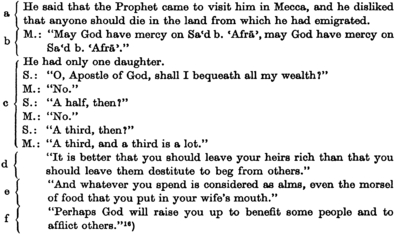

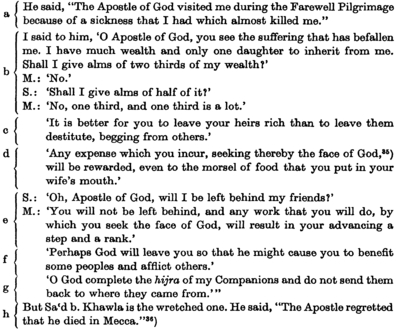

11. M. b. a. 'Umar al-Makkī, al-Thaqafī, Ayyūb al-Saklitiyānī, 'Umar b. Sa'īd, Humayd b. 'Abd al-Raḥman al-Ḥimyari, three sons of Sa'd. The Prophet went in to visit Sa'd in Mecca, and the latter wept.

M.: "Why are you weeping?"

Obviously, we cannot say that these two texts are clearly intended to give predominance to the hijra concern, but by virtue of that element's primary place in each series of motifs, it seems that their intent is to keep the question of the emigration uppermost. 11. is more elaborated than 10. since the latter is told mostly in the third person, whereas the former is in the form of a dialogue. Both texts locate the sick visit in Mecca, but no date is indicated. 10.a and 11.a link the incident with 4. Muhammad's prayer in 11.b recalls 2. and 3., but the prayer in 10.b contains an astonishing variant. Sacd is called Sa'd b. ˓Afrā˒. Of course this could have been another name by which Sa'd b. a. Waqqas was called, but it does not seem to have been cited in the biographical notices devoted to him. We shall see that one other version refers to him as the son of ˓Afrā˒ without the name, Sa'd. It is possible that this element was taken from the account of an entirely different person who was visited on his sick bed by the Prophet. The biographical dictionaries tell of three Medinan brothers of the Najjar tribe who were associated with Muhammad and who exceptionally were called by the name of their mother, ˓Afrā˒. Only one of these, Mu'adh b. al-Harith (or b. ˓Afrā˒) survived the Battle of Badr.18) Details of his subsequent life are uncertain. Some say he died in Medina of wounds received at Badr. Others affirm that he lived until 'All's caliphate. He is said to have been one of the first Anṣār to become a Muslim in Mecca. And Ibn Ḫanbal's Musnad records one tradition from him, in the isnād of which this Medinah Najjārī is called al-Qurashī.19) So, in view of this confusion it would not be surprising that some early transmitters passed on the story of Muhammad's visit to Mu˓ādh and confounded it with a similar visit to Sa˓d. In the interest of exact repetition of the text, the words, b. ˓Afrā˒ were retained, even though Sa˓d never had that name.

It can be seen that the hijra concern fits neither the life of Mu'ādh b. 'Afrā' nor that of Sa'd b. a. Waqqāṣ, who was visited for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment (see 1,), and whose illness was not originally located definitely in Mecca. So the conclusion must be drawn that the thought back of 4. was to use the sick visit (whether to Mu'adh or to Sa'd) as a vehicle for putting across the matter of emigration from Mecca.

10.c and ll.c both retain the question, Shall I bequeath all my wealth?" 11. elaborates on the subsequent exchange between Muhammad and Sa'd. giving the two motives, for asking about a will, "I have much wealth," and "My daughter will be my heir." This and 10. ("He had only one daughter") are more precise than 9., for here it is clear that Sa'd's daughter will be his only heir. However, it is not clear why he asks if he should bequeath all of his wealth, since his daughter would be entitled to some of it as her inheritance. This might be explained as a rather clumsy stage in elaborating on the incident as recorded in 5., 6., 7. and 8. That is, in specifying a motive for asking about the will (one daughter), there should be a corresponding decrease in the amount of wealth which is available for bequeathing. We shall see that in the second vertical trend of versions this detail is attended to. The expressed motivation for questioning the Prophet throws open the question of the life setting for the tradition. Do the motivation and other added elements attempt to create circumstances for a text whose original life setting is obscure? This would seem to be the case as the examination of the remaining versions will reveal.

10.d and ll.e are practically identical sayings, which constitute an element not seen before. As we shall see in one of the following versions, this statement seems to be based on an interpretation of the exchange between Muhammad and Sa'd, according to which Sa'd asked the question out of either an excessively pious desire to help others than his heirs, or an unwillingness to be generous to them. The exhortation of the Prophet is in agreement with the Qur˒ān,20) which enjoins liberality to relatives.

10.e and ll.d, also an element not seen before, represent still another interpretation of the exchange, according to which Sa'd asks how much he should bequeath to others than his family because he is troubled at the thought of not having given enough alms during his life. If this is the interpretation which is intended, then the saying in 10.e and ll.d was brought in from another ḥadīth and another life setting, to express it.21) Originally the statement about alms for this family probably owes its existence to the reluctance of certain Arab tribes to pay the legal zakāt, or ṣadaqa, as it was called in the early period.22) To mitigate somewhat the requirement, the Prophet is said to have broadened the definition of ṣadaqa to include the nafaqāt (expenditures) mentioned here.

10. and 11. are the first potpourri versions in which six elements are gathered in one and five in the other, with no concern for continuity or integration. The thought seems to have been simply to recall all that had been said on the subject.

II. The Will Concern

12. (This and the following versions form a transition, from concern with the emigration question to an emphasis-on the will. In this one the former still occupies first place, and yet it is so fragmentary that it is evidently not the main point.)

M. b. *Abd al-Bahim, Zakarīyā˒ b. 'Addī, Marwān, Hāshim b. Hāshim, 'Āmir b. Sa'd, his father.

He said, "I fell ill and the Prophet visited me.

S.: 'O, Apostle of God, pray God not to send me back to where I came from,'

M.i 'Perhaps God will raise you up and cause you to benefit other people.'

S.: 'I want to make a will, and I have one daughter. Shall I bequeath a halff

M.: 'A half is a lot.'

S.: 'A third, then?'

M.: 'A third, and a third is lot, (or a large portion).'"

He said: "So people bequeathed one third and it was permitted."23)

Muhammad's answer to Sa'd's first request is a statement not seen before. Probably it was evoked by the remembrance of Sa'd's exploits during his later life and added as a retrospective semi-prophetic utterance in the style of the manāqib (exploits) of the Companions, one of the rubrics in the ḥadīth literature.

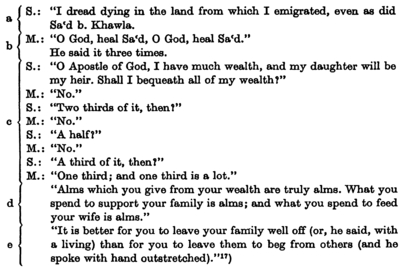

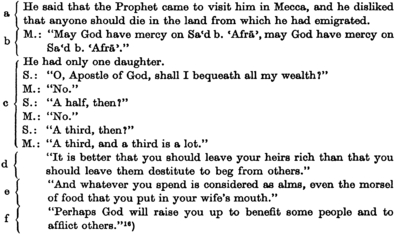

13. ˓Abd Allah, Ibn Ḥanbal, Yahyā b. Sa'd, al-Ja'd' b, Aws, 'Āisha bint Sa'd.

Sa'd said: "I became ill in Mecca and the Apostle of God came to visit me. I said, '0 Apostle of God, I have left wealth and I have only one daughter. Shall I bequeath two thirds of it and leave her one third?'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'Shall I bequeath a half and leave her a half T'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'Shall I bequeath one third and leave her two thirds?'

M.: 'A third, and a third iB a lot (three times).'"

S.: "He put his hand on my brow and then he rubbed my face, my chest and my abdomen, saying, 'O God heal Sa'd and complete his emigration.' And I imagine that I can still feel the coolness of his hand upon my heart."24)

Here the question about having only one daughter is more precise than before. The last statements of Sa'd are like an appendix to the text, constituting an explicit link with those versions which emphasize the emigration, and especially with 1., 2. and 3. The will question emerges as the mam point.

14. Ḥisham b. 'Ammār, al-Ḥusayn b. al-Ḥasan al-Marwazī and Sahl, Sufyān b. 'Uyayna, aJ-Zuhrī, 'Āmir b. Sa'd, his father.

S.: "I became ill in the year of the conquest, and I almost died. The Apostle of God came to visit me, and I said, 'O, Apostle of God, I have much wealth and only one daughter as heir. Shall I give alms of two thirds of my wealth?'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'A half, then?"

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'A third, then?'

M.: 'A third, and a third is a lot. It is better to leave your heirs rich than to leave them destitute, having to beg from others.'"25)

Here we seem to be on the same ground as in versions 6.—9., but thlre are important differences. Although the place and time have no relevance to the incident as recorded here, we are told that it took place during the year of the conquest, thus establishing a tenuous link with the hijra text (see 4.). Also Sa'd asks not if he should bequeath all of his wealth, but it he should give alms of two thirds of it. This fact, taken with Muhammad's final statement makes us think that 14. favors the interpretation that Sa'd was thinking wrongly of helping others when he should have been thinking of leaving his heirs well off. This interpretation is seen even more clearly in the next version.

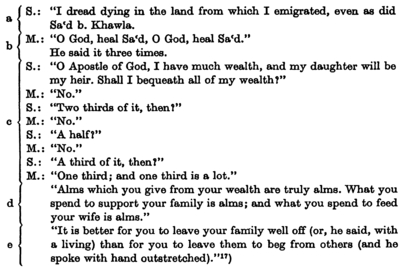

15. "Abd Allah, Ibn Ḥanbal, al-Ḥusayn b. *Ali, Zā'ida, 'Aṭā,' b. al-Sā'ib, Abu 'Abd al-Raḥmān al-Salamī

Sa'd (may God be pleased with him i) said, on the subject of the Apostle's approval(?)26) of the third: "He came to visit me and said to me, 'Have you bequeathed?'

S.: 'Yes, I am giving all my wealth to the poor and the destitute and to wayfarers.'27)

M.: 'Don't do that."

S.: 'My heirs are rich. What about two thirds?'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'A half, then?'

M.: 'No.'

S.: 'One third?*

M.: 'One third, and one third is a lot.' "28)

This version omits all mention of Sa'd s sickness or the place. It is exclusively concerned with the will, and with a particular interpretation of the question and answer exchange about the will. It is expanded into a simple story, showing good unity and creative development. No daughter is mentioned, and his heirs are rich, so he proposes to bequeath all of his wealth to others. This is clearly an enlargement upon the life setting attributed to the text by lO.d, ll.e and 14.29)

16. 'Abd Allāh, Ibn Ḥanbal, Wakī˓, Mis'ar and Sufāan, Sa'd b. Ibrahim, Sufyan from 'Amir b, Sa'd and Mis'ar from some of Sa'd's family {may God be pleased with him), Sa'd.

This is another potpourri version having the will question uppermost with all of the elements seen thus far thrown in. There is more concern here than in 10. and 11. to establish a link with the sick visit and the hijra question (see 16.d, e). 16.e recalls a mysterious son of ˓Afrā˒ whom we have seen identified with Sa'd in 10. Note the awkward jump from the third person to the first person in the introduction and the misplaced statement, like an after thought, that Sa'd had only one daughter. One of the astonishing things about the transmission of ḥadīth is that, whereas minor variants occur in large numbers and do not cause any concern to the authorities, yet on the other hand an inconsistency like the change from third person to first person here was not corrected by some rāwī. Also, Sa'd's asking if he should bequeath all of his wealth recalls the situation in 5. 7. and 8. where no daughter is mentioned. To be consistent, when the daughter is mentioned as an heir, the bequest in question should be lesj than the totality of his estate. 9. contains this same inconsistency.

The question and answer exchange is almost identical with that of 7., also from Wakī˒. So 16. merely tacks on the various extra elements, again with no apparent purpose than to cite all that had been said on the subject.

17. 'Abel Allah, Ibn Ḥanbal, 'Affān, Wuhayb, ' Allah b. 'Uthmān b. Khuthaym, 'Amr b. al-Qārī, his father, his grandfather, 'Amr b. al-Qārī.

The details elaborated in the introduction show that the incident was supposed to have taken place during the conquest of Mecca. We sense that this version has gone through more elaboration than those seen thus far, but it has not resulted- in a better integrated text thereby. Its five elements, including 17.e, a new one added by 'Amr b. al-Qārī,32) are loosely joined in the potpourri style. 17.c is added without concern to include Muhammad's prayer, for the will question is uppermost. In 17.b there is a surprising new interpretation given to the questioning about a will. Sa'd's motive is that he is going to bequeath kalālatan.33) This Quranic expression is obscure, but the most generally accepted meaning of it is that it refers to a case where the deceased person leaves neither descendant nor ascendant (lā walad wa lā wālid). So this is the fourth motivation which has been given for the incident. One was that Sa'd had much wealth, another that he had only one daughter, another that his heirs were rich, and now that he has no direct heirs. The "one daughter" versions and the "kalāla" one may indeed refer to a single interpretation, for a widely held position was that if the deceased left only a daughter, this, too, constitued kalāla, for in that case the collaterals inherited along with her. She was not entitled to the whole inheritance.34)

Although it is not clear whether this version understands kalāla as the same as "one daughter" or not, in either case, the thought in 16. is that Sa˓d was trying to excuse himself from providing for collaterals by doing good to those outside his family.

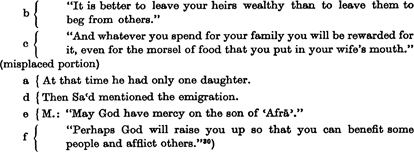

The final two versions are the best known in the standard collections of ḥadīth and show the highest degree of development.

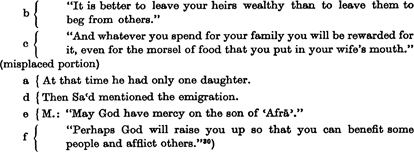

18. Yaḥyā b. Yaḥyā al-Tamīmī, Ibrāhīm b. Sa'd, Ibn Shihāb, "Āmir b. Sa'd, Sa'd b. a. Waqqāṣ.

- 19. Yaḥyā b. Qaza'a, Ibrāhīm, al-Zuhrī, 'Amir b. Sa'd b. Malik, his father.37)

This last text is almost a verbatim duplicate of 18. except that it is a little more awkwardly arranged, with several side comments as to the transmitters of certain parts of the version.

An important new element here is the dating of the incident during the Farewell Pilgrimage. Probably this came about when it became generally accepted that Sa'd b. Khawla died during that time.38) It would have been inconsistent to continue to speak of the two Sa'd's together if Ibn a. Waqqaṣ's sickness had occurred several years before Ibn Khawla's death.

All of the elements seen before are found in 18. and 19. except the beneficent touch of Muhammad and, of course, the diagnosis and treatment of Sa'd's illness, which latter details play no part in the evolution of the tradition. In addition there is one new statement, 18.e, about being left behind. This adds nothing to the picture. 18. and 19. endeavor to relate everything that has been said about Sa'd's illness.

Summary and Conclusion

Below is a diagrammatic summary of the horizontal and the vertical developments which we have noted.

When we examine versions 5., 6., 7. and 8., and then study 9. through 19. with their attempts to attach some life setting to the will concern by tacking on several different motivations and two statements drawn from other sources (18.c, 18.d), it seems that Schacht's proposed explanation for the will question is highly plausible.39) That is, the rule of no more than one third was made in the fiscal interest of the empire. If a person died, leaving no legal heirs, then his estate would belong to the government. So by restricting the amount of legacies, the state's portion would be greater.

It seems obvious that a bare statement of the question and answer, as in 5. through 8. was not sufficient for many transmitters. So there resulted the interesting evolution which we have traced.

In summary it is as follows:

A primitive story of Sa'd e illness (1.).

Another primitive story of an illness, purported to be Sa'd's, but probably that of an Ibn ˓Afrā˒ (2. cf. lO.b, 16.e), originally.

The sick visit story used as the vehicle of an emphasis on the importance of completing the hijra from Mecca (3., 4.).

The recollection of a visit to Sa'd while he was ill is used as the circumstance for a second, and probably later, teaching, no more than one third of the estate to be willed to those outside the family (5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 14., 16.).

The question about the will is given four different ostensible motivations, two of which may be the same (much wealth—11., 14.; one daughter—9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 16., 18., 19.; rich heirs—15.; no direct heirs—17.), and two different implicit interpretations (pious concern for others and neglect for family—10.d, 11.e, 14., 16.b, 17, 18, 19; uncertainty as to whether he has given enough alms during his lifetime—lO.e, ll.d, 16.c, 17., 18., 19.).

When the hijra question and the will question are combined, two trends are discernable: one which gives the hijra question primary place {10., 11.), and the other in which the main point is the will question (12. through 19.).

The way in which these disparate elements were combined to form disjointed, awkward units is an indication that most of the transmitters never achieved in their own minds a harmonious blending of the different parts. Otherwise, we should have seen a form evolved with a well-defined literary unity (according to the norms of oral literature). Taking into consideration both form and content, the only integral literary structures are seen in 1. (Biographical detail), 5. through 9., 14., 15. (Statement, Question and Answer). Evidently the guarantors of 9., 14. and 15. were not concerned with harmonizing all of the recollections of Sa'd's illness and so they passed on slightly expanded, but well integrated, versions of the simple statement of the will question (5. through 8.).

With the others, their desire was both to clarify the unelaborated will question and to link this with all that had been said about Sa'd's illness. We note that the hijra matter is only repeated as before, with no elaboration, for it had ceased long ago to be a living concern, and had become simply a biographical detail, like 1.

The following rough chronological pattern can be discerned:

1. is the oldest text.

2., 3., 4. came next, but long enough afterwards to explain the confusing of Sa'd with an Ibn '˓Afrā˒', possibly, in the form we see them, coming from the early Umayyad period, since Sa'd b. a. Waqqāṣ lived until 55/675, and this kind of confusion is most likely to have arisen after his death. This does not mean that a prototype of the hijra concern text was not circulating long before his death, however, which had nothing to do with him, personally.

5. through 19. are later, beginning sometime during the Umayyad period.

Lest it be thought that this interpretation of the evolution of the tradition is too radical, in that it rules out Sa'd as the authentic central figure, it should be pointed out that other liberties were taken with the memory of this distinguished Companion. In Ibn Sard's Ṭabaqāt40) we read that Sa'd was in Mecca once with a group of Muslims, and the idolaters of that city began to mock and slander them because of their religion. They even began to threaten them with physical violence So, Sa'd picked up a camel's jawbone and struck one of the idolaters with it and split his skull. This is said to have been the first blood shed in the history of Islam. By contrast, a text in Ibn Hanbal's Musnad, the same collection of anecdotes in which 5. is found,41) relates the following:

One day the Anṣār prepared a meal and invited us to it. We drank wine until we were intoxicated. Then the Anṣār and the Quraysh began to boast to each other. The Anṣār said, "We are better than you." And the Quraysh said, "We are better than you." Then one of the Anṣār took a jawbone of a camel (laḥy ḥazwar) and struck Sa'd's nose with it, splitting it open. So Sa'd' nose remained split.

This was the occasion for the revealing of Qur. 5:93, condemning wine drinking. This text must be considered as more authentic than the version in I.S., because it is unlikely that a text like the latter, putting Sa'd hi a good light would have been altered to one like that in I.Ḥ., which puts the Muslims and him in a bad light.

Abbreviations

- A.D. Abū Dāwud, Sunan.

- Bu. al-Bukhārī, al-Jāmi' al-Ṣaḥih.

- I.'A.B. Ibn ˓Abd al-Barr, al-Isti'āb fī Ma'rifat al-Aṣhāb.

- I. Haj., al-Iṣāba Ibn Ḥajar, Kitāb al-Iṣāba fī Tamyīz al-Ṣaḥāba.

- I.Haj. Tahdhīb Ibn Ḥajar, Talidhīb al-Tahdhīb.

- I.H. Ibn Ḥanbal, al-Musnad.

- I.'I. Ibn al-'Imād, Shadharāt al-Dhahab.

- I.M. Ibn Māja, Sunan.

- 1.S.. Ibn Sa'd, al-Ṭabaqāt al-Kubrā, Beirut ed., 1960.

- Mu. Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Cairo ed. with commentary by al Nawawī, 1349/1930.

- Qur. Qur˒ān.