The Distribution of Narrative Motifs

within the first set of traditions (1-7):

Maker Jarrar

Ich fühle des Todes

Veijüngende Flut,

Zu Balsam und Äther

Verwandelt mein Blut.

Zur Hochzeit raft der Tod

Die Lampen brennen helle

Die Jungfraun sind zur Stelle.

Novalis1

The term jihād has been the subject of numerous discussions and studies in scholarly debate in the last two decades or more.2 It is a complex category which reveals many facets: spiritual, religious, juridical and ideological. It has often been translated as "holy war" and was approached as a religious-military duty and thus sometimes associated with various ideological nationalist and fundamentalist political groups and movements, or was else studied as an integral part of Islamic international law.3

Here I am going to consider this notion from a more heuristic perspective which helps us to perceive it from a three dimensional relationship: social, ontological and communal. Holy war / jihād is regarded by many Muslim scholars as the sixth pillar of Islam,4 the first five being consecutively: 1) the belief in the oneness of God and in the message of his Apostle Muḥammad, 2) prayer (i.e. performing the daily five ritual prayers), 3) fasting during the month of Ramaḍān, 4) paying the alms and 5) the pilgrimage to Mecca once during one's life time. This religious "collective" duty of jihād5 is mentioned explicitly in the Qur˒an as well as in the canonical ḥadīth compendia, where a whole chapter is usually dedicated to it. But throughout the history of Islamic communities and Islamic states this duty has been interpreted and applied in different manners, according to how it was ideologically conceptualized at a certain historical moment.

We possess, however, a separate book on jihād which goes back to the third quarter of the second / eighth century,6 i.e. to the same period when al-Shaybānī (d. 189 / 804) was compiling the first theoretical and juridical work on jihād.1 This book does not deal with the legal aspect of this duty but discusses the merits of those who accomplish it and the rewards which await them in the Hereafter. It was the first work in a parœnesis genre which came to be known as "the merits of holy war" (faḍā˒il al-jihād). It is remarkable how some of the traditions of this book and their underlying motifs have been taken over in later compilations to be treated as topoi8 around which long narratives have developed, and which resemble in their structure many Arabic folk tales and popular narratives. When we reach the sixth / twelfth and seventh / thirteenth centuries, during the time of the Crusades, we notice that these tales have taken their final form. They used to be read in crowds and in market places by orators and specialized storytellers to arouse the enthusiasm of the crowd and to help recruit new warriors. Thus they function as 'myth'9 going beyond a mere literary genre, for they come to serve a diversity of goals on the social, ideological, and gender levels.

I would like to say a word about the author and the book before I move on to analyze its contents. The author of this book is the famous traditionalist (muḥaddith) ˓Abd Allāh b. al-Mubārak (d. 181/797),10 from whom we possess two other books on asceticism. Ibn al-Mubārak was born in Marv (in Turkmenistan today) of Turkish stock; he embarked upon his religious studies and when he was around twenty years of age, he undertook a journey to continue his studies in various Islamic centers under well known teachers and authorities of the time (al-riḥlah fī ṭalab al-˓ilm). He was soon regarded as an authority among the religious scholars, especially the Sunnites, as well as among the ascetics of his time. He was a wealthy merchant, who granted stipends to ḥadīth-students and financed volunteers who took part in military campaigns. The early sources agree that he used either to participate in such campaigns or undertake the pilgrimage to Mecca in alternate years. He died in a town on upper Euphrates upon his return from a military venture. The manuscript of Ibn al-Mubārak's book, which is the first of its genre, is an uniqum that goes back to the middle of the fifth / eleventh century. It is worth noting that a time span of more than one hundred years separates the first transmitter of this book from the author. Thus the role of this first transmitter, Sa˓īd b. Rahmah al-Maṣṣīṣī, is rather that of a compiler, who seems to have gathered these traditions which go back to Ibn al-Mubārak and put them into book form.11 Studying more closely the transmission chain of this book found on the first page, one concludes that the first three transmitters12 are from Mopsuestia (al-Maṣṣīṣa), a strategic town on the northwestern Syrian border with Byzantium.13 This means that this book was in circulation there and used to be read among the volunteers (mujāhidūn or muṭṭawwi˓ah). It consists actually of a compilation of 262 traditions of varying length, all dealing with the merits of holy war and the rewards of the martyrs in the Hereafter. They follow one another haphazardly, have no introductory statement, and end abruptly. As already mentioned, these traditions were circulating in the frontier towns on the Islamic-Byzantine boarders where Ibn al-Mubārak used to take part in the campaigns. At that time, during the second half of the second / eighth century the main threat to the Islamic empire came from the Byzantines, who took advantage of the events of the ˓Abbāsid revolt against the Umayyads and the riots in Syria that followed, to launch attacks all across the frontier lines. They devastated many strongholds and castles and regained strategic towns and positions.14 The ˓Abbāsid caliphs, mainly al-Mahdī (158 / 774-169 / 785), took the initiative and rebuilt the frontier towns and castles and fortified new positions. He manned the frontiers with new troops from amongst the regular army. He also encouraged volunteers (muṭṭawwi˓ah) to reside in the frontier fortifications and take active part in the campaigns.15 These volunteers were mainly pious men who understood jihād as a Qur˒anic duty incumbent upon each and every individual, a personal matter of worship and sacrifice, or a convention between God and his servants.16 Yet, with the tendency of the state to centralization and institutionalization, and the desire of the caliphs to control and monopolize the religious as well as the military functions, mainly by recruiting military slaves, a feeling of bitterness and discontent spread among wide factions of the ˓ulamā˒ who regulated local communal and religious life by serving as judges, administrators, teachers and religious advisers to Muslims17 - as well as of ascetics and other groups that were struggling with the state over the control of many offices and institutions.18 As Lapidus puts it: "the development of religious authorities independent of the caliphate was coupled with the emergence of 'sectarian' bodies within the Islamic ummah. From a religious and communal point of view, the caliphate and Islam were no longer wholly integrated."19

Against this institutionalization process of the army, the ˓ulamā˒ were spreading as early as the last quarter of the first / seventh century prophetic traditions which stressed the function of jihād as a personal sacrifice which is the right of each and every Muslim and that jihād will not cease until the last troop / company of believers will fight the anti-Christ.20 The celebrated Medinan jurisconsultant Mālik b. Anas (d. 179 / 795) had forbidden that one should fight under the banner of the state army.21 This took place sometime around the middle of the second / eighth century, most probably after the ˓Abbāsids had crushed the revolt of al-Nafs al-Zakiyya in (145 / 762). Nevertheless, he gave a legal opinion (fatwā) after the atrocious defeat of the Muslim army by the Byzantines near Mar˓ash in 161 / 778-162 / 779, permitting the jihād with the unjust rulers (a˒immat al-sū˒).22

By the middle of the third century the separation between the functions of the state and those of the ˓ulamā˒ had been established and a new consensus was reached: "Obedience to the ruler is obligatory; riots, civil strifes and shedding of blood are interdicted; praying and jihād are to be performed with each ruler, whether pious and righteous or not" (al-ṣalātu wa-l-jihādu khalfa kulli imām barran kāna aw fājiran).23 Among the volunteers were a number of ascetics and scholars who took active part in the battles. Two names are of significance here, namely, Ibn al-Mubārak and Abū Isḥāq al-Fazārī (d. 186 / 803). Both have written books on the faḍā˒il al-jihād, although al-Fazārī's book deals in the first place with legal questions of war, a collection of responsa.24 Our interest here lies mainly in Ibn al-Mubārak's book. From among the 262 traditions that are mentioned therein, thirteen share a common motif: that of the Paradise Virgins (al- ḥūr al-˓īn), a theme which is mentioned five times in the Qur˒ān as a heavenly reward for the believers.25

All thirteen traditions mentioned have as their first link narrators who died some time between the end of the first / seventh and the second / eighth century. At a time, hence, when the expeditions against Constantinopel were succeeding without interruption since the middle of the first century and its conquest was perceived as one of the last signs of the End times.26 The narrators of these traditions (akhbār) were either ascetics from Baṣrah or warriors who took part in campaigns on the Syrian frontier. Some of them are known to have been storytellers:

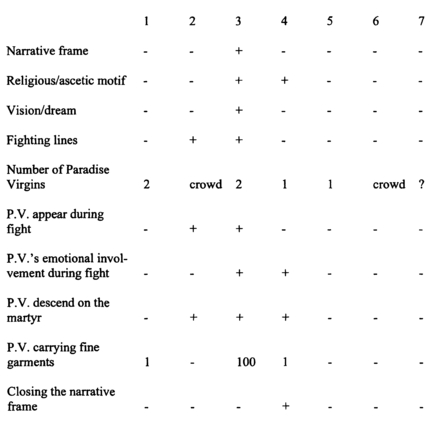

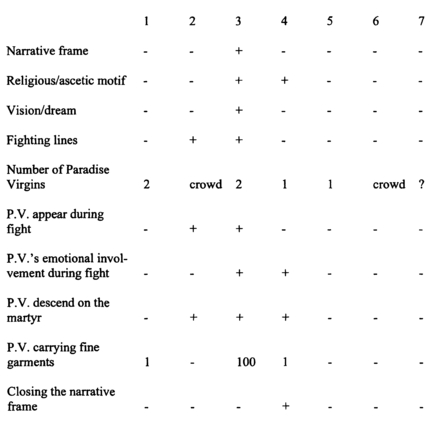

I have divided the traditions into two groups according to their components. The first group includes the first seven traditions (K. al-Jihād, nos. 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 63, 132). They are direct, have a simple form, and reveal the recurrence of two constants:

(A) the appearance of the Paradise Virgins (always in pairs) occurs during fight and with their active encouragement, without the "hero" being aware of them;

(B) the immediate passage to the ḥūrīs directly upon his "heroic death.

In juxtaposition to these constants, two variants appear in these traditions which are:

(C) the ḥūrīs wear / or cany a very fine paradise garment (nos. 1, 3, 4, 5 = K. al-Jihād, nos. 20, 22, 23, 24);

(D) a comparison (in the ḥurīs favor) between the ḥūrīs and the earthly martyr's wife.

I should say a word about traditions no. 3 and 6 (= K. al-Jihād, 22 and 63). No. 3 reveals a narrative form which is more elaborate than the others. Here both the constants and the variants are used to build up a new complex; a narrator (rāwī) appears for the first time, who associates the ritual prayer with holy war, and experiences a "vision". No. 6 brings a new dimension, an act of transfiguration: the martyr receives a new body (a new form) and looks back upon his earthly relatives with mixed feelings of triumph and malice. With the second group of traditions (K al-Jihād, nos. 143, 146, 147, 145, 149, 150, 148 and Ibn Abī Zamanīn: Qudwah, 243-45) we are already dealing with a tale. Here we have a frame story (Rahmenerzählung) told by a first narrator. A "hero" takes over to tell his story and portrays his "vision" (this vision often takes the form of a dream). He then leaves the scene to the first narrator and his colleagues who play the role of focalization (al-sard ḍimna l-sard). The components of this group of traditions are five:

The Distribution of Narrative Motifs

within the first set of traditions (1-7):

(A) a first narrator (with his colleagues), who prepares the frame story / Rahmenerzählung;

(B) the vision of the "hero (here comes the main motif of the Paradise Virgins), told in the first person;

(C) the first narrator takes over;

(D) a sudden attack, i.e. death of the "hero" (who is the second narrator), usually correlated with the fulfilling of a religious duty, such as fasting or prayer;

(E) the closing of the Rahmenerzählung through a comment by the first narrator.

These components are fused together through certain topoi and verbal cliches that reappear in all these traditions and which we will discuss later. The turning point in all of them is the vision; it either occurs in a dream, or during a period of loss of consciousness due to a fatal wound, or even sometimes in a daydream. It is through the vision that the "hero" is transferred to the world of the Paradise Virgins where he experiences glorious things and is invited to come in flesh to possess the Virgins and participate in their magnificent world. However, he must first experience martyrdom, the hour of which is set by the Virgins. It is through the vision that the hero is able thereafter to communicate to his fellow-warriors the "good news", being overwhelmed by a state of ecstatic joy. In one of the variant stories the hero meets immortal youths (ghilmān mushammirūn) "boys with tucked-up garments."28 This "passage" of the "hero" to an "unreal", fantastic world makes out of him a "mythical hero". Thus, the hero goes through "rites of passage": separation from the world, a penetration to some source of power; and a life-enhancing return. He comes back filled with creative power which is indispensable for the continuation of spiritual energy into the world.29 Although the "hero" dies directly after his return, nevertheless, he brings to his community a flame of positive, creative power and opens for them a highway to eternity and everlasting life of joy before he dies a heroic death, witnessing for his transfiguration with his blood. The dream or the vision in these stories has a specific function: it opens an outlet to the hero into the fantastic world of the Paradise Virgins. Dream is personalized myth30 and the dreamer carries with him all the longings and the hopes of his people. The dream is here a literary dream31 and has thus a semiotic function.32 The dreams we are dealing with here can be called "revelation dreams";33 for the dreamer / visionist communicates through them with heavenly creatures which represent a divine reward, and moreover he returns to reveal to his people "good news" that have a religious connotation and affirm a certain religious concept.34 Furthermore, the dream takes place within the framework of a religious duty (jihād).

Dreams represent here a literary topos and they serve two functions: 1) they confirm the religions belief in the Paradise Virgins, 2) and they motivate the religious duty of jihād. Their contents are moreover of a theological nature that relates to a certain group having common belief and a common heritage, i.e. the belief in an eternal life in the Hereafter, and the assertion of the destiny of the martyr, who does not pass through an interval period in the tomb (ḥayāt barzakhiyyah),35 but directly receives his eternal place in a joyous paradise.

We have till now followed the different stages through which these traditions have passed; 1) their initial germ is the qur'anic idea of the Paradise Virgins which are promised to the believers in the Hereafter; 2) this germ was first shaped in the circles of exegetes and ascetics to appear as short verses attributed to early scholar-warriors who took part in the campaigns on the Syrian-Byzantine borders; 3) the decisive phase was achieved when these short verses were elaborated by storytellers to reach a certain literary standard; 4) through their long span of oral transmission and circulation in these circles, they became more refined and new narrative motifs seeped into them such as the vision-motif and the "rites of passage"; 5) it was then that they were put into writing.

All these traditions (akhbār) share a common theme which reveals two facets: Death / Paradise Virgins or Eros / Death. Both facets represent an innermost, crucial part of existence. They make up the totality of its positive and negative potencies. "Being" is moving towards death. In this it is incited by a positive power in itself (i.e. Eros) which on the one hand effectuates and fulfills "being" in time, but at the same time drives it to its ultimate realization, i.e. Death. Furthermore, Eros represents the highest aim of the being's dispositions and longings. It moreover intensifies these desires and brings them to their end. Therefore it contains its antithesis within itself.36 One of the main manifestations of the Eros is the sexual love which strives to unite with an object to reach the "optimization of the intrinsic pleasures by discourse that accompanies them", as Foucault puts it.37 Yet, this passion only achieves its climax through lust joined with pain which burns each time it is fulfilled, a process which ends in death.38

To escape his "uncanniness", the human being has aimed since time immemorial, at fulfilling passionate love through reunion with "the sacred" to give his desires an eternal realization which transcends death,39 so that the positive energy Eros could negate death. The war instinct has always been coupled with the passionate Eros.40 Holy war is one way to offer pain as a sacrifice to "the sacred" in return for the perpetuation of Eros which constitutes the essence of "being". Through pain and through offering himself as a blood sacrifice (i.e. sacrificing one's "being"), the "hero" purposefully explodes into death aiming at eternalizing his desires and longings in the everlasting presence of "the sacred". He displays the "entirety of being" in order to sustain "the essence of being," i.e. the Eros.41 The Paradise Virgins are mentioned in the Qur˒ān as a reward for the believers in the Hereafter, where this reward could be interpreted as sensual descriptions with allusions to the lively raptures.42 Some exegetes had understood these descriptions literally, whereas mystic exegetes have interpreted them as symbols.43 Furthermore, some modern students have considered that they represent the righteous deeds of ancient Persian culture.44 It is not my aim in this paper to study the different positions of Muslim exegetes regarding their understanding of the possible interpretations of the Paradise Virgins; my main interest lies rather in the connection between jihād and the Paradise Virgins, i.e. between Eros and Death, a theme which recurs in different cultures. I have already illustrated that this is a qur˒ānic understanding which was developed further within the circles of Syrian and Iraqi scholar-warriors, ascetics and story-tellers on the threshold of the second century after the hijrah. A report about the famous ascetic Ḥātim al-Aṣamm of the early third / ninth century, mentioned by the renowned Sufi author al-Qushayrī (d. 465 / 1073), portrays this relation very clearly:

Ḥātim al-Aṣamm said: "We were with Shaqīq al-Balkhī fighting in a row against the Turks in a day where one could only see flying heads and broken spears and swords." Shaqīq said to me: "How do you feel today, Oh Ḥātim, isn't it the same feeling as on your wedding night?" I replied: "No, by God not!" Shaqīq said: "But I do have that feeling." He then went to sleep between the two [fighting] rows with his shield beneath his head. I could even hear him snoring.45

We find here again the same literary topos which we discussed earlier, although it is taken for granted here that the reader is already acquainted with it. For this report does not mention details as if it is enough to mention the "wedding night" while one is falling asleep (i.e. in a dreaming state) amidst a severe fight to experience the pleasures of the wedding night, a fact that recalls in the memory of the reader the lascivious scenes of the Paradise Virgins. Lust here, therefore, supersedes pain although there is no direct mention of fighting, pain or even death. The Islamic tradition emphasizes that the pain of death, when fighting, is no more than the pain of a pinch.46 The mention of the "wedding night" makes us directly recall the "holy wedding" (heilige Hochzeit), death which represents usually the end of the Eros becomes now a way to eternalize aphrodisia, in a state separated from pain, an eternal life which renews itself in the presence of "the sacred". Holy war / jihād in the cause of "the sacred" represents the threshold of eternal happiness and joy, through which the cycle of the "rites of passage", that is represented through the formula "Eros-Death-Eternal Eros" finds its ultimate realization.

As we know from the sources these volunteers, even the ascetics among them, were usually married;47 Islam encourages marriage and a certain tradition attributed to the Prophet states that "there is no monasticism in Islam, for jihād is the monasticism of my community" (rahbāniyyatu ummatī al-jihād).48 Some of them were even living with their families as armed monastics (murābiṭūn) in frontier towns. In only one case do we find that the "hero" was a young single man who had made up his mind to get married directly after he comes back from the campaign. Nevertheless, the Paradise Virgins appeared to him in a dream and invited him to a "sacred wedding," and he died fighting the day after.49 We can take these thirteen traditions from Ibn al-Mubārak's book as a starting point to study the development of this genre which reached, its maturity in the sixth / twelfth and seventh / thirteenth centuries. Some of the traditions mentioned by Ibn al-Mubārak were adopted in later compilations from other parts of the Islamic empire, such as in Iraq, Iran or Islamic Spain. Moreover, there appeared exhortation works written by specialized public preachers (wu˓˓āz) and storytellers (quṣṣāṣ) that incite people to participate in jihād, with the aim of recruiting volunteers, especially during the Crusader's time, exhorting religious morals, and spreading orthodox dogmas in a simplified way. They also reveal public spiritual preoccupation (Geistesbeschäftigungen). These works included long narratives on the theme of 'holy war and the Paradise Virgins'.50

Not all of these compilations have survived. In some cases I was not able to identify their authors whose names were only mentioned in other books. But we do possess a two-volume work by Ibn al-Naḥḥās, a Syrian author from the eighth / fourteenth century (d. 814 / 1411) that deals with jihād, its legal aspects and its merits, entitled Mashāri˓ al-ashwāq ilā maṣāri˓ al-˓ushshāq (The stilling wells of yearnings which lead to the battle grounds of passionate lovers). This work contains many of these narratives and cites their sources. These are stories built around the theme of "holy war and the Paradise Virgins"; they include long, elaborate narratives (some of which exceed four pages) with a frame-story (Rahmenerzählung), characters around the "hero", monologues and action. A main narrator (rāwī) in three of these long stories5' is ˓Abd al-Wāḥid b. Zayd al-Baṣrī,52 a renowned ascetic and a distinguished public preacher from Baṣrah who was one of the founding fathers of the ascetic school of ˓Abbādān, and who died in the last quarter of the second / eighth century. In a source of the fifth / eleventh century,53 'Abd al-Wāḥid b. Zayd is said to have seen the Paradise Virgins in dreams, talked to them, and had even been recited a poem by one of them. We notice that all three stories, whose narrator is ˓Abd al-Wāḥid b. Zayd, include poetry in their narrative describing the Paradise Virgins and praising them.54 Actually, this introduction of the theme of the Paradise Virgins in verse form substitutes the function of the dream / vision which is lacking in these narrations. It seems that Ibn al-Mubārak himself had written a poem in this regard which used to be recited both in public and in private scholarly circles. We have evidence that it used to be recited in Qayrawān around the middle of the third / ninth century,55 the time when the Muslims of Qayrawān were undertaking their jihād in Sicily.

New motifs appear in these stories which reveal that they underwent a long process of oral tradition and redaction after they had been documented as written material. A whole spectrum of well known popular Islamic heroes are mentioned in them, such as Maslama ibn ˓Abd al-Malik, who was a main figure in the fights against the Byzantines during the first / seventh century and to whom a whole popular "Roman" (sīrah) was dedicated.56 They tend to mention places connected to well known victories against infidels. Furthermore, many of these motifs reflect popular beliefs and practices or dogmatic and religious preoccupations that help us to trace the various stages and Sitz im Leben through which they passed. In one of them, for example, the mother offers the ponytail of her hair as an ornament to the horse of a warrior (here Abū Qudāmah al-Shāmī, the narrator himself) in order to acquire blessings (barakah or mana).57 It should be mentioned that hair in popular tradition refers to sexual energy and supernatural power; the cutting of hair, moreover, is analogous to the practices of redemption.58 In another story59 a mother dedicates her only son to jihād in the path of God after her husband and brothers have been killed in holy war as martyrs; this is an allusion to the tradition attributed to the Prophet which asserts that "the martyr mediates in the day of resurrection for seventy of his clan and close relatives."60

In a third story61 a theological phrase is put in the mouth of a young warrior who justifies his taking part in the fight, which is not a legal duty upon him because of his young age. He cites an orthodox slogan which was in circulation among some theologians during the third / ninth century62 which states that "God might torment even younger children than I if they disobey Him". In still another story a mother dedicates her son to jihād in the hope that he marries a Paradise Virgin,63 so she pays as his dowry a sum of money to the warriors in order to buy weapons. Serving as witnesses to this marriage were Qur˒ān reciters (qurrā˒) who took active part in the fight; her son sends her a message while in the throes of martyrdom with one of these qurrā˒ saying: "Oh, mother your wish is fulfilled and your dowry accepted; I got married to the bride."64 The sacred wedding has been accomplished here through a ritual embedded with religious symbols and in which fighters from amongst the Qur˒ān reciters took active part. A common feature in all these stories is their attitude towards women, who are reduced to a copulative body given as a reward for male violence, i.e. a kind of a booty. It is true that these narratives are centered around Qur˒ānic phrases which serve their attitude towards the female body, but their articulation, nevertheless, is formed according to cultural and social characteristics which are revealed through the reduction of the women to passive, perpetually desired bodies, eternally available for serving aggressive and powerful men. They are the representation of a male-centered society, which perceives the female and her body as a subordinate object.65 These are male narratives (the narrators are all male, as well as the protagonists and the aggressive setting of war), which represent an articulation of gender politics of a patriarchal social structure.66 They are, as I will argue, a reflection of a society of males, who had a peripheral social status, and were not able to integrate in the society's norms seeking thus a refuge in a newly self-fantasized world, a society of ascetics-warriors, whose relation to women and the female body was distorted, so that the relation which is restrained by love and marriage, i.e. sex which is protective, is reversed into its opposite: a self-centered gratification which projects a fear of the female body and reduces it to a sheer maternal substitution, i.e. the Paradise Virgins as a substitute to a female rejection - the "mythical women" as a maternal substitute.

Many of these narratives reflect the disturbed relationship to women through a comparison between the Paradise Virgins and the earthly wife, which ends always in the Virgin's favor, as well as by making the earthly wife an object of ridicule or by the "hero" expressing a feeling of ill will towards her. Even in the longer narratives, where the narrative discourse (sjuzet) is more elaborated and new characters appear, the female is still absent. Only the mother appears here to take a secondary role which facilitates the passage of her son to the heavenly maternal substitute. To try to put it in a Lacanian frame,67 these narratives signify the absence of the symbolic father, who is neither real nor present, but who is manifested through systems of exchange:

a) language, which have the creative power, the power of unking through fantasy the unconscious and conscious systems;

b) marriage customs;

c) social institutions and the inherited laws of culture given by a mythical father, whose image is translated into a conventional or institutional figure, a "hero", who penetrates the private sphere of the Paradise Virgins, that is to say a figure that goes with a hierarchic, linear and "discursive" vision of time and narrative, where it is evident that what is at stake is a reassertion of the authority of conventional models, i.e. lost sons drifting through the awes of war as they await reunion with the figure of the mythical mother, never doubting that they (i.e. the sons / heroes) have been personally chosen to carry out the divine will. To these sons fall the duties and the debts of a patriarchal law and its dominant social values.

I will stop here to summarize the results of this study: these stories underwent many stages before they developed into a genre; they emerged in the milieu of the late first / seventh and early second / eighth century ascetics, and storytellers of Syria and Basrah at a time when there was still no clear cutting line between storytelling and "official" ḥadīth. Their origins were short reports whose first "setting in life" (Sitz im Leben) was Qur'anic exegetic literature and they served in inciting a zeal for jihād and recruiting volunteers at a time when Islamic communities were settling in towns and becoming more urbanized. They found their written form in the second half of the second / eighth century to build up the kernel of a new genre known as "the merits of holy war" (faḍā˒il al-jihād). The first written book in this genre, as far as we know, is the Kitāb al-Jihād of Ibn al-Mubārak. Although we meet often in later compilations of this genre the name of ˓Abd al-Wāḥid ibn Zayd who was a contemporary of Ibn al-Mubārak, we find no extant book of his. Ibn al-Mubārak's book consists mainly of material which did not meet certain standards to be adopted in "orthodox" ḥadīth-compendia but remained nevertheless in circulation amongst ascetics and storytellers of the different Islamic regions from Islamic Spain in the West to Iṣfahān in the Northeast. This material would eventually work its way into the fabric of popular culture although it sustained its original form as "religious tradition". It accordingly did not develop as pure popular narrative such as the stories of ˓Antarah, al-Zīr, or al-Baṭṭāl in the narrative of Dhāt al-Himmah but prevailed mainly in spheres of scholars with popular and ascetic leanings.

An intermediary stage in the development of this genre can be seen in the work of Ibn Abī Zamanīn, an ascetic of the fourth / tenth century from Islamic Spain (al-Andalus). The main bulk of Ibn al-Mubārak's material appears in Ibn Abī Zamanīn's book entitled A Model for the Warrior (Qudwat al-ghāzī), after being modified and embellished with new motifs and clichés.

The decisive age when this genre reached its zenith and became closer to folk narratives was during the sixth-seventh / twelfth-thirteen centuries, i.e. during the age of the Crusades, where these narratives, in their elaborated form, appear in the oratory compilations of authors such as Ibn Ṭāhir al-Sulamī al-Dimashqī (d. 500 / 1106), Sibṭ ibn al-Jawzī (d. 654 / 1256) and Hibat Allāh b. ˓Asākir (d. 620 / 1223). A comparison between the reports mentioned by Ibn al-Mubārak and later long narratives reveals that the later stories have achieved a life of their own as a separate genre.

The motif of the Paradise Virgins coupled with martyrdom during jihād appears as well in historic narrations: In an account which resembles in its structure popular folk literature dealing with the campaign of Maslamah ibn ˓Abd al-Malik and quoted by Ibn A˓tham al-Kūfī (314 / 926),68 where the virgins appear upon the death of the three heroes and the narration is closed by verses of poetry describing the Virgins. Or in an account mentioned by al-˓Imād al-Iṣfahānī describing the martyrdom of the military leader Aḥmad ibn al-Malik al-Muẓaffar during the siege of Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Ayyūbī on al-Ramlah in 573 / 1177.69

This motif recurs as well in modern Islamic literature on jihād, especially in pamphlets, martyrs' testimonies and commemorations from Iran70 and Gaza strip in Palestine.71 In a commemoration speech during the ceremony held on the fortieth (arba˓ūn) of the martyrdom of ˓Iṣām ˓Azīz Brāhmeh (Barāhimah) from Gaza, his fiancée says:

I have accepted (am pleased: irtaḍaytu) that my wedding should be a Palestinian wedding, which does not end in a single (battle) field or in a single night. For this is the Palestinian wedding which is mixed with blood and adorned by the tunes of bullets. And this is our destiny: that the mother should light (the way) by (sacrificing) her son, and the sister should miss her brother, and the wife should offer willingly her husband as a girt tor the Paradise Virgins, whereby we make one wedding procession after the other.72

The sacrifice or the ransoming is now done in the name of the mother, i.e. the "homeland". The ˓āshiq or the "cosmic spouse"73 is offering himself for the beloved mother in the name of the whole community. This is a theme which recurs in modern Palestinian poetry and prose, where the popular tarwīdah (popular wedding song)74 is used as a leitmotif by a number of poets and writers. Nevertheless, I did not come across well elaborated variations on this theme in the new literature of the "Islamists" in Palestine or Lebanon.

* This paper is based 011 my study in Arabic Maṣāri˓ al-˓'uššāq: dirāsah fī aḥādīth faḍl al-jihād wa 'al-ḥūr al-˓īn' which was published in al-Abḥāth (American University of Beirut) 41 (1993), 27-121. I had the opportunity to further elaborate my research during my stay as a visiting Professor at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University (1996). I would like to thank Profs. W. Heinrichs and W, Granara for reading the manuscript and suggesting valuable comments on language and style.

1 "Hymnen an die Nacht", in: Gesammelte Werke. Ed. Carl Seelig. Heidelberg/ Zürich 1945. Vol. I, 15, 21.

2 It is not my aim here to give a full bibliography of the numerous modern studies on jihād. I will confine myself by mentioning only those studies of which I made direct use. Cf. for example M. Watt: Islam and the Integration of Society. London 1961, 61-67, 130ff.; A. Noth: Heiliger Krieg und heiliger Kampf im Islam und Christentum. Beitrag zur Vorgeschichte und Geschichte der Kreuzzüge. Bonn 1966; J. Kelsey and J. Turner Johnson (Eds.): Just War and Jihād. New York 1991; id.: Cross, Crescent, and Sword. New York 1991; M. Jurgensmeyer: Violence and the Sacred in Modern World. London 1992; Muḥammad S.R. al-Būṭī: al-Jihād fī l-Islām. Damascus / Beirut 1993; Kh .Y. Blankinship: The End of the Jihād State. Albany 1994, 11-21.

3 M. Khadduri: War and Peace in the Law of Islam. Baltimore 1979.

4 Muslim scholars have differentiated between the 'greater jihād' which is struggling with oneself against oneself and one's sins and 'smaller jihād' which takes the form of war. Even the smaller jihād is regarded as a 'collective duty' (farḍ kifāya) and not as an 'individual duty' (farḍ 'ayn), except in some restricted cases, cf. al-Buti: al-Jihād, 19ff, 46ff. And for a contrary understanding of some militant Islamic groups cf. M.˓A. Faraj: al-Farīḍah al-ghā˒ibah (English translation and study by J. Jansen).

5 Cf. for example Z. al-Qāsimī: al-Jihād wa-l-ḥuqūq al-dawliyyah al-˓dmmah fī l-Islām. Beirut 1982, 154ff., 251ff.

6 ˓Abd Allāh Ibn al-Mubārak: Kitāb al-Jihād. Ed. N. Ḥammād. Beirut 1971.

7 M. Khadduri: The Islamic Law of Nations. Baltimore 1966.

8 On this concept cf. E.R. Curtius: Europäische Literatur und lateinisches Mittelalter, München 1969; L. Fischer: "Topik", in: Grundzüge der Literatur- und Sprachwissenschaft. Vol. I: Literatur. München 1990, 157-164; L. Bornscheuer: "Topik", in: Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturgeschichte. Vol. IV, Berlin / New York 1984, 454-75; for Islamic literature cf. A. Noth: Quellenkritische Studien. Bonn 1973 (cf. now the English version).

9 J. Campbell says in "The Masks of God": "through mythology man touches something immortal." For S. Ausband: "Myths work by demonstrating order. They are true in the sense that they are satisfactory demonstrations or representations of a perceived order and are therefore often believed by a society to be more or less factual." Both citations from S. Ausband: Myth and Meaning, Myth and Order. Macron, Georgia 1983, 5.

10 al-Qāḍī 'Iyāḍ: Tartīb al-maḍārik. Rabat 1968. Vol. III, 36-51; Ibn Manẓūr: Mukhtaṣar Ta'rīkh Dimashq. Ed. R. al-Naḥḥās. Damascus 1988. Vol. XIV, 13-31; al-Dhahabī: Ta'rīkh al-Islam. Ed. ˓U.˓A. Tadmurī. Beirut 1990, 19 (181-190h.), 228-48; id.: Siyar a˓lām al-nubalā˒. Ed. Sh. Arnā˒ūṭ. Beirut 1981-1988. Vol. VIII, 336-371; al-Mizzī: Tahdhīb al-Kamāl. Ed. B.˓A. Ma˓ruf. Beirut 1980-1992. Vol. XVI, 5-25; F. Sezgin: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums. Leiden 1967. Vol. I, 95; J. Robson: art. "Ibn al-Mubārak", in: EI2, Vol. III, 879; P. Nwyia: art. '"Abdallāh B. Mobārak" in: EIr, Vol. I (1985), 184f.; as far as I know three monographs on Ibn al-Mubārak in Arabic treat him as an exemplary model. Cf. as well R.G. Khoury on the reception of his K. al-Jihād in Ibn Ḥajar al-˓Asqalānī's Iṣābah, in: Studia Islamica 42 (1976), 115-146.

11 Cf. Jarrar, in: al-Abḥāth, 30f.

12 Sa˓īd b, Raḥmah, Muḥammad b. Sufyān al-Ṣaffār and Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad (d. 385/995).

13 Ibn Shaddād: A˓laq al-khaṭīrah. Ed. Y. ˓Abbārah. Damascus 1991. Vol. I and II, 144-149; F. ˓Uthmān: al-Ḥudud al-islāmiyyah al-bīzanṭiyyah. Vol. I-III. Cairo 1966, Vol. II, 250ff.; E. Honigmann's art. "Maṣṣīṣa": in: EI2 Vol. VI (1986), 774-779; id.: TAVO-maps (B VI 8).

14 ˓Uthmān: al-Ḥudūd al-islāmiyyah, Vol. I, 134f., 283ff., 332ff.; ˓A.M. 'Abd al-Ghanī: al-Ḥudūd al-bīzanṭiyyah al-islāmiyyah wa-tanẓīmātuhā al-thagriyyah. Kuwait 1990, 33.

15 ˓Uthmān: al-Ḥudūd al-islāmiyyah, Vol. II, 145-58, 250ff.; I. ˓Abbās: Tārīkh bilād al-shām fī-l-˓asr al-'abbāsi 132-255/750-870. Amman 1992, 79-83; M.˓A. Sha˓ban: al-Dawlah al-'abbāsiyyah. al-Fāṭimiyyūn 650-1055/132-448. Beirut 1981, 41; J. Arvites: "The Defense of Byzantine Anatolia during the Reign of Irene (780-802)" in: Armies and Frontiers in Roman and Byzantine Anatolia. Ed. S. Mitchell. Oxford 1983, 219-237.

16 A. Noth: Heiliger Krieg, 43ff.; id.: "Heiliger Kampf (Gihad) gegen die "Franken". Zur Position der Kreuzzüge im Rahmen der Islamgeschichte", in: Saeculum 36 (1986), 240-59; M. Jarrar: Die Prophetenbiographie im islamischen Spanien. Ein Beitrag zur Überlieferungs- und Redaktionsgeschichte. Frankfurt / M. 1989, 243ff,

17 Cf. R. Mottahedeh: Loyalty and Leadership in Early Islamic Society. New Jersey 1980, 135ff.

18 Kh. Yuce-soy: Taṭawwur al-fikr al-siyāsi 'inda ah! al-sunnah. Amman 1993, 83-118.

19 I. Lapidus: "The Seperation of State and Religion in the Development of Early Islamic Society", in: IJMES 6 (1975), 363-385, 369; id.: "Die Institutionalisierung der frühislamischen Gesellschaft", in: Max Webers Sicht des Islams. Interpretation und Kritik. Ed. W. Schluchter. Frankfurt/M. 1987, 125-141.

20 ˓Abd al-Razzāq: Muṣannaf. Ed. H.R, al-A˓ẓamī. Beirut 1971, Vol, V, 279; Ibn al-Mubārak: K. al-Jihād, no. 43; M. Jarrar: "Sīrah, Mashāhid, and Maghāzī: The Genesis and Development of the Biography of Muḥammad", in: Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Ed. A. Cameron and L.I. Conrad. New Yersey: The Darwin Press, 1997, Vol. III, 1-43, 41f.

21 Saḥnūn; al-Mudawwanah al-kubrā. Cairo 1905. Vol. III, 5; Ibn Abī Zamanīn: Qudwat al-ghāzī. Ed. ˓A. Sulaymānī. Beirut 1989, 223; M. Jarrar: Die Prophetenbiographie, 244, 270, fn. 8.

22 Cf. fn. 21.

23 Ibn Ḥanbal: 'Aqīdah. Ed. A.I. al-Sīrawān. Beirut 1988, 65, 68, 72, 75f., 123f.; Ibn ˓Abd al-Barr: al-Tamḥīd. Rabat 1967. Vol. I, 3; al-Būṭī: al-Jihād, 112-117; Kh. Yuce-soy, Taṭawwur, 167ff.

24 K. al-Siyar. Ed. F. Ḥamāda. Beirut 1987.

25 Qur˒ān: 44,54; 52,20; 55,72; 56,22; 78,32-34, On the subject of the "Paradise Virgins" cf. E. Berthels: "Die paradiesischen Jungfrauen im Islam", in: Islamica 1 (1925), 263-288 and 543 (J. Horovitz); D. Künstlinger: "Die Namen und Freuden des kuranischen Paradieses", in: BSOAS 6 (1930-32), 629-632; T. Andrae: Mohammed, sein Leben und sein Glaube. Stockholm 1917, 69-75; id.: Les Origines de l'Islam et le Christianisme. Trans. J. Roche. Paris 1955, 151-161; E. Beck: "Eine christliche Parallele zu den Paradiesjungfrauen des Korans", in: OCP 14 (1948), 398-405; J. Macdonald: "Islamic Eschatology VI-Paradise", in: Islamic Studies 5 (1966), 352-360. For the Islamic tradition cf. Wensinck: Concordance et indices de la tradition musulmane. Leiden 1936, Vol. I, 526; al-Qurṭubī: al-Tadhkirah fī aḥwāl al-mawtā. Ed. al-Sayyid al-Jumaylī. Beirut 1986. Vol. II; 633-640; Ibn Kathīr: Ṣifat al-jannah wa-mā fihā min al-na˓īm al-muqīm. Ed. Yūsuf ˓A. al-Budaywī. Beirut 1989, 96ff., 102-114, 153-157; Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: Ḥādī al-arwāḥ. Cairo 1907. Vol. I., 341-392, Vol. II, 2-7.

26 Cf. M. Jarrar: "The Sīrah: Its Formative Period and its Transmission", in: BUC Public Lecture Series. Beirut, April 1992.

27 I am relying on V. Propp's: Morphology of the Folk-Tale. Trans. L. Scott. Austin / London: University of Texas Press, 1968 as a starting point to examine these themes and motifs.

28 Qur˒an: 76,19. These "ghilmān mushammirūn' remind one of the Ganymede in Greek culture, cf. K. Dover: Greek Homosexuality. New York 1978, 197-198.

29 J. Campbell: The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New Jersey 1968, 29-40, 49ff.

30 Ibid., 19.

31 On literary dreams, cf. L.M. Porter: "Real Dreams, Literary Dreams, and the Fantastic in Literature", in: The Dream and the Text. Essays on Literature and Language. Ed. C.S. Rupprecht. Albany 1993, 32-47.

32 Cf. on this F. Malti-Douglas: "Dreams, the Blind, and the Semiotics of the Biographical Notice", in: Studia Islamica 51 (1980), 137ff., and for dreams in Islamic biographical works: L. Kinberg: "Interaction between this World and the Afterworld in Early Islamic Tradition", in: Oriens 29/30 (1986), 285-308; id. "The Standardization of Qur˒an Readings: The Testimonial Value of Dreams", in: Proceedings of the Colloquium on Arabic Grammar, Eds. K. Devenyi and T. Ivani. Budapest 1991, 223-238.

33 Cf. hereto A.L. Oppenheim: The Interpretations of Dreams in the Ancient Middle East. Philadelphia 1956, 185ff.

34 Cf. R. D'Andrade: "The Effect of Culture on Dreams", in: Dreams and Dreaming. Eds. S.M. Lee and A.R. Mayes. New York 1973, 203f.

35 J.I. Smith and Y. Haddad: The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection. Albany 1989, 7-9, 32f. and see index (barrier).

36 Cf. C. Schneider: "Eros", in: RAC 6 (1966), 306-311; H. Buchner: Eros und Sein. Erörterungen zu Platons Symposion. Bonn 1965, 133ff.

37 M. Foucault: The History of Sexuality. New York 1988. Vol. I, 170.

38 Cf. S. Freud: Beyond the Pleasure Principle. New York / London 1961, 47ff.; and the critical revision of this theory by A.J .Levin: "The Fiction of the Death Instinct", in: Psychiatric Quarterly 25 (1951), 257-281.

39 Cf. Ph. Camby: L'Erotisme et le sacre. Paris 1989, chaps. 1 and 3; on the 'sacred wedding / heilige Hochzeit' cf. J. Schmied: "Heilige Brautschaft", in: RAC 2 (1954), 527-564; Campbell: The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 109-120.

40 D. De Rougemont: Passion and Society. Trans. M. Belgion. London 1956, 243ff.; G. Bataille: Erotism. Death and Sexuality. Trans. M. Dalwood. San Francisco 1986, 71ff. For the recurrence of this theme in modern Arabic literature, cf. now M. Cooke's "Death and Desire in Iraqi War Literature", in: Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature. Eds. R. Allen, H. Kilpatrick and E. de Moor. London 1995, 184-199.

41 Cf. Foucault: History of Sexuality, Vol. I, 155f.

42 Cf. A. Bouhdiba: Sexuality in Islam. London / Boston 1985, 72-87; F. Rosenthal: "Reflections on Love in Paradise", in: Love and Death in the Ancient Near East. Ed. J.H. Marks and R.M. Good. Conneticut 1987, 247-254. He says: "the description of the huris in paradise are in no way explicitly sexual in the sense that they were said to gratify coarse sexual desires of the blessed in paradise. The implication of sexuality is, however, unmistakable." See the critical comments of Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī on the subject (249). An article on the theme of the Paradise Virgins has appeared recently by A. al-Azmeh: "Rhetoric for the Senses: A Consideration of Muslim Paradise Narratives", in: JAL 26 (1995), 215-231. Al-Azmeh does not deal in his article with the theme of jihād. He does not seem to know my monograph, cf. fh. 1.

43 Cf. Ibn ˓Aṭā˒ al-Adamī, in: P. Nwyia: Nuṣūṣ ṣūfiyyah. Beirut 1973, 154; Ibn al-˓Arabī: Tafsīr al-shaykh al-akbar al-˓arif bi-llāh. Bulāq 1281h.. Vol. II, 268, 284f., 290f.; Ibn al-˓Arabī: al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyyah. Ed. U. Yaḥyā. Cairo 1974. Vol. III, 153f.

44 E. Berthels: "Die paradiesischen Jungfrauen (Huriṣ) im Islam", in: Islamica 1 (1925), 263-288. For modern studies on the theme of the Paradise Virgins cf. my article in al-Abḥāth, 37, fn. 3.

45 al-Qushayrī: al-Risālah fi ˓ilm al-taṣawwuf. Eds. Ma˓ruf Zurayq and ˓Alī ˓Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Balṭajī. Beirut: Dār al-Jīl, 1990, 398; cf. as well F. Meier: "Sufik und Kulturzerfall", in: Bausteine. Ausgewählte Aufsätze zur Islamwissenschaft. Eds. E. Glassen and G. Schubert. Stuttgart / Istanbul 1992, Vol. I, 20; A.E. Khairallah: "The Wine-cup of Death: War as a Mystical Way", in: Quaderni di Studi Arabi 8 (1990), 171.

46 Ibn al-Naḥḥas: Mashāri˓ al-ashwāq ilā maṣāri˓ al-˓ushshāq. Eds. Idrīs M. ˓Alī and M. Iṣṭanbūlī. Beirut 1990. Vol. I, 114, Vol. II, 751 f.

47 T. Andrae: Islamische Mystiker, Ed. H. Kanus-Crede. Stuttgart 1960, 54-66.

48 Although jihād in this tradition should rather be understood as one's endeavor to control one's desires (al-jihād al-akbar), still it was interpreted by Ibn al-Mubārak as a military striving, cf. Ibn al-Mubārak: K. al-Jihād, 35f.; Ibn al-Naḥḥas: Mashāri˓ Vol. I, 164-168.

49 Ibn al- Mubārak, K. al-Jihād, no. 149; Ibn al-Naḥḥas, Mashāri˓, Vol. I, 361f.

50 Cf. Jarrar in: al-Abḥāth, 67-110; and cf. Ibn Abī al-Dunyā: K. al-Manāmāt. Ed. A. ˓Aṭā˒. Beirut 1993, 98f.

51 Ibn al-Naḥḥās, Mashāri˓, Vol.I, 215-218, Vol. II, 689-690, 775-777.

52 On him cf. Ibn ˓Asākir: Ta 'rīkh Dimashq, Vol. X, 552-562; Ibn al-Jawzī: Ṣifat al-ṣafwah. Ed. M. Fākhurī and M.R. Qal˒ajī. Beirut 1979. Vol. III, 321-325; al-Dhahabī: Ta'rīkh al-Islām, Vol. XVIII, (171-180h.), 251-253; L. Massignon: Essai sur les origines du lexique technique de la mystique musulmane. Paris 1922, 191-197; Ch. Pellat: Le milieu baṣrien et la formation de Ğāḥiẓ. Paris 1953, 99-105.

53 Ibn al-Jawzī: Ṣifat al-ṣafwah, Vol. III, 323f.

54 Cf. Ibn al-Naḥḥās, Mashāri˓, Vol. I, 215-18; Vol. II, 689C, 775-777; al-Yāfi˓'ī: Rawḍ rayd̄ḥīn fi ḥikāyāt al-ṣāliḥīn. On the margin of al-Tha˓alibī: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā˒. Cairo 1883, 109-112.

55 al-Mālikī: Riyāḍ al-nufūs. Ed. B. Bakkush. Beirut 1981-1984. Vol. IV, 41 Of.; see other verses dealing with the theme of the Paradise Virgins in Ibn al-'Arabī: al-Futūḥāt, Vol. VIII, 244.

56 Cf. al-Khaṭīb: Ta'rīkh Baghdād. Cairo 1931, Vol. IX, 338; M. Canard: "Les Expeditions des Arabes", in: Journal Asiatique 208 (1926), 80ff.; H.-G. Beck: Geschichte der byzantinischen Volksliteratur. München 1971, 69ff.

57 Ibn al-Naḥḥās: Mashāri˓, Vol. I, 285ff. and Vol. II, 690ff.

58 Cf. Ch. Hallpike: art. "Hair", in: Encyclopaedia of Religion. Ed. Mircia Eliade. New York / London, 1987. Vol. VI, 154-157; H. Kxiss: Volksglaube im Bereich des Islam. Wiesbaden 1960-1962. Vol. I, 72, 188, 28; Vol. II, 48, 190f.

59 Ibn al-Naḥḥās: Mashāri˓, Vol. I, 215ff.

60 Cf. Jarrar, in: al-Abḥāth, 78, no. 13 and 86, 4-5, 90, 1. This tradition is quoted in a testament left by one of the martyrs of the Islamic movement in the occupied Gaza strip, cf. Shuhadā˒ ma˓a sabq al-iṣrār. Ḥarakat al-Jihād al-Islāmī, Filasṭīn 1993, 52.

61 Ibn al-Naḥḥās: Mashāri˓, Vol. I, 287.

62 M. Watt: The Formative Period of Islamic Thought. Edinburgh 1973, 240ff.; J.I Smith and Y. Haddad: The Islamic Understanding of Death, 157ff.

63 Ibn al-Naḥḥās: Mashāri˓, Vol I, 215-218.

64 Jarrar, in: al-Abḥāth, 91.

65 On the attitude of Medieval Arabic literature towards women cf. Fedwa Malti-Douglas: Woman's Body, Woman's Word. New Jersey 1991.

66 In a female narrative such as the frame-work of Alf laylah wa-laylah where Shahrazād is the narrator, "body has been transmuted into word and back into body (...) Shahrazād relinquishes her role of narrator for that of perfect woman: mother and lover", as F. Malti-Douglas puts it in: Woman's Body, 28. Cf. as well S. Naddaff: Arabesque. Narrative Structure and the Aesthetics of Repetition in 1001 Nights. Evanston, Illinois 1991, 98ff.

67 I have relied on the following books: The Fictional Father: Lacanian Readings of the Text. Ed. R. Con Davis. Amherst 1981; M. Bowie: Freud, Proust and Lacan: Theory as Fiction. Cambridge 1990; J.M. Mellard: Using Lacan, Reading Fiction. Chicago 1991.

68 Ibn A˓tham al-Kūfi: Kitāb al-Fuṭūḥ. Haydar Abad: Dā˒irat al-Ma˓ārif al-˓Uthmāniyyah, 1974, Vol. VII, 181.

69 ˓Imād al-Din al-Isfahānī: al-Barq al-shāmī. Ed. Muṣṭafā al-Ḥiyarī. Amman: Mu˒'assasat ˓Abd al-Ḥamīd Shumān, 1987, Vol. III, 39.

70 Cf. hereto W. Schmucker: "Iranische Märtyrertestamente", in: Die Welt des Islams 27 (1987), 236-242; A. Khairallah, 184ff.

71 Cf. the commemoration and pamphlets of Dr. ˓A. al-Rantīsī, Kh. Muḥjiz, Dr. ˓I. al-˓Aryan and Hamas (Gaza Faction), in Gh. Daw˓ar: 'Imād ˓Aql: Usṭūrat al-jihād wa-l-muqāwamah. London 1994, 164, 178, 180, 181, 199 (consecutively).

72 Shuhadā˒ ma˓a sabq al-iṣrār, 65.

73 Cf. A. Neuwirth: "Israelisch-palästinensische Paradoxien," in: Quaderni di Studi Arabi 12 (1994), 103-108.

74 Cf. M.M. al-Bakr: al-˓Urs al-sha˓bī (al-Tarwīdah). Beirut 1995, 99-128.