4

DREAM INTERPRETATION

And so a dream is a kind of time-space doodle that uses the remembered forms of waking experience as its circles, squares, and triangles.

B.O. States, Seeing in the Dark: Reflections on dreams and dreaming

Because of their unique standing outside the regular bounds of space and time, dreams have often been thought to contain hidden meanings or secrets that need to be interpreted in order to be understood properly. Books have been written for millennia listing samples of dream images and their possible interpretations. From ancient Egypt, however, while the Late Period and later is well-represented by a large number of Demotic dream-texts, 1 only one dream book has survived dating to the period with which this book is concerned. Reconstructed and published by Gardiner in 1935, 2 this compilation is contained on P. Chester Beatty III, RECTO 1–11, and dates to the Ramesside Period. It is possible that this uneven distribution in evidence for dream-omina, and the absence of earlier documents related to dream interpretation, may be explained by the vagaries of chance preservation. It is also possible that the Egyptian perception of dreams was not monolithic and did not remain static over the centuries, and the appearance of books devoted to dream interpretation reflects a change in the value and function of dreams in Egyptian society. While it is implau sible to suggest that P. Chester Beatty III is the actual first Egyptian book of dream interpretation, it may reflect a new technique for acquiring information that only developed in the New Kingdom. Ray has suggested that the Egyptians’ need for divination as a means to control fate intensified after the New Kingdom, particularly in the Late Period. 3

The classification of any ancient Egyptian text can be a complicated matter, and the Ramesside Dream Book is no exception. While there seems to be a consensus in Assyriological circles that the Mesopotamian dream-omina should be regarded as scientific texts, 4 the issue has been scantily addressed in reference to the Egyptian texts. Groll was the first to address this in detail, and she treats this papyrus as a ‘grammatical text which tries to systematize a specific technical dream language of literary Late Egyptian’. 5 Significantly, Groll enlarges her description and classifiesit as a ‘type of medical text specializing in dream interpretation, that is,the translation of the visual imagery of dreams into words’. The medical texts also are organized as a series of conditional clauses with the symptoms as antecedent, followed by a brief diagnosis, and ending with a treatment as the consequent. The conditional clauses in the Egyptian Dream Books consist of visual images as antecedent, a diagnosis of the dream as either positive or negative, and finally an interpretation as the consequent. In the medical texts, the nature of the symptom leads to a particular response or treatment. A similar relationship may have existed between each dream and its resulting effect in the Dream Book. Rather than the dream simply revealing an event which was destined to occur whether or not a particular image was seen, some dreams may have been thought to trigger a specific response. For example, the passage ‘If a man sees himself in a dream looking through a window; good (it means that) his call be heard by his god’ (r. 2.24), does not necessarily imply that his call would have been heard whether or not he saw that particular image. Rather, the image itself provokes the god into listening to the dreamer.

The connection between each dream image and its interpretation was not random, but was based on the Egyptians’ conceptual system of that time. A similar structure was used in a New Kingdom omina-calendar, which Vernus concludes arose from a view that may be called ‘scientific’, if we understand the ancient world as apprehending the universe as an infinite organisation of homologues and analogies, with each object being the sign of all the others. 6

The ancient methods of ‘science’ were different from that of the modern Western world, but upon closer examination a certain familiar rational approach may be discerned in the treatment of dreams and divination. In this approach, dreams are considered to be codified manifestations of some kind of higher order which can be decoded and understood by a specialist. 7 Oppenheim, in reference to the mantic techniques of Mesopotamia, a nation in contact with Egypt, considers

it essential for the understanding of Mesopotamian divination – and that includes dream omens – to see in it a ‘science’, that is, a willingness to face reality, a willingness endowed with the same seriousness of intent and the same innate global aspiration that characterize that aspect of our modern relation to reality which we call science.

(Oppenheim, ‘Mantic dreams in the ancient Near East’, 342)

More recently, Stephan Maul, in his study of Babylonian and Assyrian ‘Namburbi’ rituals, discusses the classification of divinatory practices in Mesopotamia. He notes that the study of natural portents that developed in the second and first millennia should not be labelled as ‘superstition’. 8 Rather, he agrees with Oppenheim’s assessment and concurs that different divinatory methods developed according to a standardized science, and could be learned only after a long period of study. 9 Much like western scientific thought, the presence of a god is not foregrounded in the early stages of Egyptian dream interpretation. In stark contrast to oracles which require the presence of a god or a divine representative, 10 the dreams are treated as omens: fixed signs which portend good or bad events without necessarily requiring the intervention of a deity. They would require interpretation, however, which could be provided by a Dream Book, or perhaps by a consultant.

The interpreters of dreams

That dream interpretation was a feature of Hellenistic Egypt is undisputed. For example, the archive of Hor of Sebennytos provides us with a large corpus of dreams and their meanings dating from c. 170 BC. 11 As with the evidence for oneiromancy itself, much of our current knowledge regarding the identity of the Egyptian dream specialists stems from Greek, Coptic, or Near Eastern sources. Nevertheless, even with this later information, the origins of oneiromancy remain obscure.

By examining the primary sources, however, one finds that the evidence of Egypt’s supposed reputation in the area of professional dream interpretation prior to the Ptolemaic Period is highly problematic and consists largely of three non-Egyptian references. One of these references is found in the well-known passage of Gen. 41, where Joseph is able to interpret the dream of the pharaoh after the ḥarṭummîm fail. The word ḥarṭummîm is not a native Hebrew word, but has been assumed to be a foreign term, probably Egyptian, and related to the lexeme ḫarṭibi. The latter is attested in Akkadian sources as a title after three personal names in a text from the reign of Esarhaddon (680–669 BC) 12 and again in a list of Egyptian prisoners and craftsmen from the reign of Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC). 13 According to the CAD, ḫarṭibi is an Egyptian word meaning ‘interpreter of dreams’ and is compared to the Hebrew ḥarṭōm. 14

Based on these Akkadian sources, the conclusion has been drawn that Egypt was an important oneiromantic centre at the time (roughly the end of the Kushite dynasty). For example, in one analysis of the divinatory economy of the ancient Near East15 Sweek emphasized that although a wide variety of divinatory techniques enjoyed a high status in Assyrian society and politics, oneiromancy as an institution did not seem to be included in the traditional scholarly disciplines. 16 Instead, based on the Akkadian sources mentioned above, it seemed that dream professionals were imported, particularly from Egypt. Sweek stresses that ‘Esarhaddon’s resort to foreign oneirocritics demonstrates the simplest means of controlling dreams within the academy. One seeks out specialists from another cultural reference, where dream divination is a specialization, or presumed to be so.’ 17 But this argument is only true if ḫarṭibi means ‘dream interpreters’, and this definition is based largely on the affinity of the Akkadian term to the Aramaic/Hebrew ḥarṭummîm. This lexeme, however, does appear elsewhere in the Bible in contexts completely unrelated to dreams, where the word clearly does not mean ‘dream interpreter’. 18 The major Hebrew-English lexicons recognize this, and the first meaning listed for the root ḥarṭom in the Brown-Driver-Briggs lexicon is ‘engraver’, 19 and in the Koehler-Baumgartner it is ‘fortune telling’ and ‘magician’. 20

It should also be remembered that this particular episode in Genesis was likely composed as a literary narrative, rather than a historical record. 21 Although Egypt was chosen as the setting for the scene, it was ultimately written for an Israelite audience, and reflects the practice of dream divination with which that audience would have been familiar. 22 The point of the episode is that Joseph is the successful dream-interpreter, and not the Egyptian ḥarṭummîm who appear unfamiliar with the practice of dream interpretation and indeed are singularly inept in helping their pharaoh. Noegel points out that the redactors of the Bible characterized foreigners as unable to decipher their own dreams, unlike their Israelite counterparts. 23 While magicians, such as the ḥarṭummîm, and other non-Israelite practitioners of divination are referred to as outsiders in the Hebrew Bible, 24 dreams themselves as a means of gaining knowledge were well known and not prohibited. 25 This was the case as well in the rest of the Mesopotamian world, where dream interpretation enjoyed a long and distinguished history26 without requiring recourse to Egyptian expertise.

The case for ḥarṭummîm and ḫarṭibi meaning dream-interpreter is further weakened upon examination of the possible Egyptian source of these words. If these terms derive from the Egyptian, ḥry-tm⫖ (‘the one on the mat’), 27 ḥry-tp or ḥry-tb (‘chief), or h̲ry-ḥb ḥry-tp (‘chief lector-priest’) 28 as has been suggested, there is no evidence that these were technical terms for dream interpreters in Egypt. On the contrary, the most popular candidate, ḥry-tp, and the Demotic ḥry-tb, 29 appeared in numerous contexts with the meaning ‘magician’. 30

Searching Egyptian biblical sources, one finds that in the Bohairic dialect of Coptic, the word used in Gen. 41 is  which was probably derived from the ancient Egyptian sh̲ pr-‘ᒼnḫ ‘Scribe of the House of Life’. 31 In the Sahidic version the word

which was probably derived from the ancient Egyptian sh̲ pr-‘ᒼnḫ ‘Scribe of the House of Life’. 31 In the Sahidic version the word  is used instead. Although this word is derived from rmṯ jw.f w⫖ḥ rsw ‘the man who interprets dreams’, this title does not appear in the ancient Egyptian texts, and was likely inferred based on context. In other passages of the biblical tale these individuals are called cšou ‘learned men’. 32 Whether or not one accepts any of these tentative etymologies, the evidence for ḫarṭibi or ḥarṭummîm meaning ‘dream specialists’ remains inconclusive, and based mostly on context and tradition. These individuals should instead be considered either as wise men, magicians, or priests who did not necessarily have much experience at all in the practice of dream divination, or at best practised oneiromancy as one of their many specialities. While dream interpretation was practised, perhaps as early as the Late Period, and definitely in the Hellenistic Period, during that time there seems to have been no identifiable word or expression referring to Egyptian oneirocritics as a distinct category. Rather, dream divination seems to have been just one of the priestly activities under the auspices of the ‘House of Life’. 33 It has recently been suggested that rather than being one of the functions of the lector priests (ḥry-tb), the interpretation of dreams, at least in the Ptolemaic Period, may have instead been part of the duties of the pastophoroi (a class of individuals that Ray describes as ‘semi-priests’). 34

is used instead. Although this word is derived from rmṯ jw.f w⫖ḥ rsw ‘the man who interprets dreams’, this title does not appear in the ancient Egyptian texts, and was likely inferred based on context. In other passages of the biblical tale these individuals are called cšou ‘learned men’. 32 Whether or not one accepts any of these tentative etymologies, the evidence for ḫarṭibi or ḥarṭummîm meaning ‘dream specialists’ remains inconclusive, and based mostly on context and tradition. These individuals should instead be considered either as wise men, magicians, or priests who did not necessarily have much experience at all in the practice of dream divination, or at best practised oneiromancy as one of their many specialities. While dream interpretation was practised, perhaps as early as the Late Period, and definitely in the Hellenistic Period, during that time there seems to have been no identifiable word or expression referring to Egyptian oneirocritics as a distinct category. Rather, dream divination seems to have been just one of the priestly activities under the auspices of the ‘House of Life’. 33 It has recently been suggested that rather than being one of the functions of the lector priests (ḥry-tb), the interpretation of dreams, at least in the Ptolemaic Period, may have instead been part of the duties of the pastophoroi (a class of individuals that Ray describes as ‘semi-priests’). 34

The earliest references to dreams in ancient Egypt are found in the First Intermediate Period letters to the dead. Here they function as a sort of liminal zone in which the barriers between the world of the living and the world of the dead become temporarily translucent, allowing the living and the dead to view each other. In the Middle Kingdom, they appear as malignant forces to be repulsed and avoided in medical and execration texts, and they function primarily as literary devices in belles lettres and wisdom texts. The earliest currently-known report of an Egyptian individual consulting any sort of technician, professional or otherwise, for help concerning a dream is found in P. Deir el-Medina 6 – a Ramesside letter from Deir el-Medina. 35 In this letter, an anonymous scribe36 writes a letter to an addressee concerning his (the addressee’s) female friend who has come to visit. The scribe writes to his friend, telling him that he is sending this message in secret (verso 1–3): 37

[The woman X has] run away to the village. Now look, I have taken charge of her. I didn‘t let her see that I had written to you saying ‘She’s here.’ Actually, it is because of a dream that she has come in order to stand in the presence of Nefertari. Look after her and don‘t do what you have usually done!

The writer of the letter emphasizes that he did not want the woman to know that he was revealing her presence in the village to his correspondent. Our lack of context and other substantiating evidence, however, leaves us unable to ascertain whether it was simply the presence of the woman in the village that was to be kept secret, or her visit to Nefertari. 38 The phrase ‘to stand in the presence of’ (m-b⫖h) is often used to indicate an oracular consultation. 39 From our understanding of the technology of oracles, it seems that they did not usually give detailed responses, but rather answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’, or signalled a response from among a number of previously written possibilities. 40 The woman in the letter might have been inspired by a dream to go to the oracle, or her goal may have been to ask the goddess whether the dream was a positive or a negative omen. At least one other example of an oracular consultation concerning a dream is attested by a small ostrakon from Ramesside Deir el-Medina inscribed with the question: ‘As for the dreams which one will see, will they be good ones?’ 41 It is conceivable that this type of question was asked by the dreamer in our letter. There is no firm evidence whether this dreamer might also have obtained a fuller interpretation, or whether a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response sufficed. In any case, assuming the woman was in search of guidance regarding a dream, it is clear that she did not take her troubles to a professional dream interpreter, but rather to a goddess. This letter, along with the oracular ostrakon, suggest that in the New Kingdom, questions regarding dreams were brought to the presence of a divine oracle, rather than a professional interpreter. But we have as yet not discussed the most important surviving piece of evidence for the practice of dream interpretation: the Ramesside Dream Book.

Ramesside Dream Book

Because P. Chester Beatty III remains our only evidence of a compilation of dreams and their interpretations prior to the Late Period, it deserves close attention. In 1928 an assemblage of religious, magical, documentary, and literary papyri was discovered in Deir el-Medina in the superstructure of a tomb between the base of a pyramid and the vault of a chapel, in a small trapezoidal space. 42 Koenig speculates that this collection may have been placed in this area in order to protect it during the chaotic period at the end of the twentieth dynasty. 43 The group of texts was originally part of the archive of the well-known scribe Qenherkhopshef, a scribe from Deir el-Medina. The collection includes a diverse assortment of letters, memoranda, documents related to family and domestic affairs, exercises, belles-lettres, and texts that Pestman calls ‘semi-literary’ (such as ‘medical prescriptions, prophylactic spells, incantations against scorpion’s stings, the dream book, and other texts which may have had the scope of being something like "practical handbooks for daily use" ’). 44 Some were written in Qenherkhopshef’s distinct hieratic handwriting, some were gifts, and some, such as the Dream Book, may have been bought – perhaps from a House of Life. It is clear that Qenherkhopshef himself was not the author of the manual, as the verso of the papyrus, as well as little leftover nooks and crannies were filled with texts written in his handwriting, which was markedly different from the handwriting of the Dream Book portion. The complexity of the punning and sophistication of language argues for its composer as having been one of the scribal elite of Egypt, that is the priesthood. 45 Even though Qenherkhopshef was not himself the composer, nor was he a professional priest, he was a member of the village of Deir el-Medina where Ritner has suggested that ‘in the absence of a professional priesthood, workers acted as their own priests, and thus had access to material restricted elsewhere’. 46 After Qenherkhopshef died childless, his wife remarried, and the library was passed down to her son Amunnakht, son of Khaemnun. This Amunnakht added a colophon to the Dream Book, falsely attributing its creation to himself. 47 As it passed from owner to owner, the library increased in size, though individual papyri suffered the indignity of being torn for reuse. 48 The Dream Book itself shows evidence of having been torn at some point prior to the death of its final owner. 49

It is unknown whether Qenherkhopshef or any other members of that family actually used the Dream Book to interpret their own dreams or those of others. It is entirely possible it was kept simply for the papyrus itself as writing material, or as a curiosity, on a bookshelf as it were, like a first edition classic might be held by an avid collector, who has no intention of actually reading the book. Qenherkhopshef was after all an avid collector of a wide variety of texts. But we may also question just how useful the content of this manuscript was to Qenherkhopshef. While the roll itself did remain in his family, he used the verso of the papyrus as a convenient surface for his writing out portions of the Ramesses II battle of Kadesh poem, as well as writing a copy of a letter from himself to Merneptah’s vizier. 50 Nor are we able easily to establish if the document was frequently used before it reached the library of Qenherkhopshef. The height of the papyrus roll (35 cm) suggests that the Dream Book was kept as an official document, but the extant to which it might have been used in Egyptian society remains unknown. Structurally similar texts, such as the Calendars of Lucky and Unlucky Days, 51 have been found from the Middle Kingdom on, but only in temple contexts, leading some to suggest that their use was restricted to the priesthood. 52 The Dream Book is the only New Kingdom specimen (so far), and with no other documentation attesting to its use it is even more difficult to determine what, if any, impact it might have had on the lives of the Egyptians of this period.

What can be tentatively proposed, is the segment of the population whose dreams it explains. It is notable that the Ramesside Dream Book recounts dreams that a man, not a woman, may have. 53 This is not only an accident of the gender in the initial phrase ‘If a man sees himself in a dream ...’, but is made abundantly clear throughout the text. For example, the activities mentioned are ones typically performed by Egyptian men, while references to the woman or wife of the dreamer certify the dreamer’s sex as male. A sharp contrast can be found in the Demotic Dream Book written a millennium later, which includes three categories of dream images that specifically women might see, perhaps pointing to a wider audience for the use of the Dream Book. One of these categories is labelled specifically as ‘The types of sexual intercourse about which one dreams [...] about which a woman dreams’ (n⫖ h̲ nkt.w mtw rmt nw r[.r-w (?r) wc .t(?)] sḥjm.t nw r.r-w). 54 While this is not the venue for an analysis of the Demotic Dream Book, all the extant categories of dream images that a woman may see in the Demotic text consist predominantly of fornication with, giving birth to, or the suckling of various animals, as opposed to the non-sexually specific categories of drinking specific kinds of beer and wine, or swimming with different types of people. 55 Thus, these passages seem to correspond to the negative representations of women which are reflected in Demotic wisdom texts. 56 The fact that a section of the Demotic Dream Book does enumerate dreams specifically experienced by women – and Oppenheim states that this is ’a unique feature in Near Eastern dream books’ 57 – tends to confirm the impression that women held a relatively high level of legal rights and standing in Ptolemaic Egypt. However, we cannot say with certainty that the Ramesside Dream Book did not contain dreams experienced by women, as a large portion is missing and it could potentially have contained additional categories of dreams.

In P. Chester Beatty III the dreams and their interpretations are quite brief and strongly reflect their cultural matrix, much like the dream dictionaries one can easily find in book stores today. The relationships between the individual images and interpretations are based largely on word plays, as well as underlying myths and the cultural values of the time. The content of the dreams thus echoes to a certain extent the stresses, anxieties, wishes, values, and realities of Egyptian society. The question remains, however, as to whose concerns these dreams reflect. The composer of the text was a member of the literary elite, whose skills in the subtleties of wordplay and grammar suggest a high level of expertise, so the text could have been composed as a literary exercise, reflecting the author’s own hopes and fears. Alternatively it could be an actual record of numerous dreams which an interpreter or priest might have heard over the years, used for daily consultation, or archived as an important resource, or to preserve an oral tradition. Closer examination of the papyrus as a physical artefact may provide further clues, but these questions are complex, and may ultimately remain inconclusive.

For the purposes of the present discussion, this dream book will be treated as a text written during the Ramesside age, reflecting the cares of the townspeople of a village such as Deir el-Medina. Certain elements of this text, such as frequent allusions to townspeople (njwtj.w), the description of the Sethian man (discussed below), as well as the occasional unflattering reference to officials, 58 correspond to our reconstructions of life in that village and strongly suggest this context, but we should not lose sight that this is but one scenario.

Dating

Based on the later writing on the verso of the text by Qenherkhopshef, and a careful study of the palaeography of the RECTO, Gardiner dates the Dream Book portion of the papyrus to the early years of Ramesses II. 59 He further tentatively suggests that its contents may date back to the Middle Kingdom, contending that the ‘language is pure Middle Egyptian, [and] the spelling throughout is that of early Ramesside times’. 60 The use of Middle Egyptian, however, may be attributed to the author’s intention to lend authenticity to the text and to elevate its status, as well as its appropriateness as the ‘scientific language of hemerology’. 61 Gardiner’s analysis of the grammar has been strongly contested by Groll, who describes the text as a ‘grammatical text which tries to systematize a specific technical dream language of literary Late Egyptian’. 62 While I am not entirely convinced by the details of Groll’s linguistic analysis, there is other evidence to support a New Kingdom origin for the initial compilation of the text. Certain of the text’s Middle Egyptian attributes can be explained by its function as a practical or technical manual. As described in Chapter 2, the expression rsw.t continues to be used in king’s novels, spells, and belles-lettres, throughout Egypt’s history. The phrase qd comes into vogue only in the New Kingdom, and then only in the documentary texts of non-royal Egyptians. Hensel (forthcoming) notes that certain terms in the Dream Book, such as gsgs (r. 10.5; Wb V 207; DZA 30713720), s-c ḫj (r. 4.11; Wb IV 54.9; DZA 2897250), ḏnw (r. 6.7; Wb V 575.6; DZA 31632140) and wrry.t (r. 9.7; DZA 22535470) are only attested in writing from the time of the New Kingdom. Furthermore, she lists a number of correspondences between certain phrases found in the dreams related to the divine in the Dream Book, and Assmann’s listings of phrases found in New Kingdom hymns and prayers that reflect personal piety.

The formulation of the lists as conditional structures (‘if X then that means Y) is a feature of diagnostic texts such as medical texts and the Calendars of Lucky and Unlucky Days. While examples of the latter are found from the Middle Kingdom, no examples of dream interpretation have yet been found from that time. Finally, certain puns and metaphors used in the text are remarkably similar to those found in other New Kingdom texts, such as the Instruction of Amenemope. This does not imply that the authors of these texts necessarily were aware of each other’s texts, but that those particular word-plays were prevalent in that age.

Evidence frequently cited for an early belief in the mantic function of dreams is the following passage in the Instruction of Merikare (ll.136–7):

jrj.n=f n=sn ḥk⫖.w r c ḥ⫖.w r ḫsf c .w n.t ḫpr.yt

rs.wt ḥr=s grḥ mj hrw.(w) 63

Some scholars have translated this passage as ‘He made for them magic as weapons to ward off (evil) events; dreams (also) by night and day.’ 64 On this basis it has been claimed that as early as the Middle Kingdom the Egyptians believed that ‘dreams are sent by the gods so that man may know the future’. 65 This in turn has been used to help bolster an early dating for the Dream Book. New studies, in particular those by Quack, 66 have resolved the ambiguity of this passage, which should properly read:

He has made for them magic,

as a weapon to oppose the blow of events,

watching over them, night and day. 67

The lexeme rs.wt here is not the substantive ‘dream’, but rather the nominal form ‘to guard, watch over’. This has at times been said to refer indirectly to dreams, 68 but rsj is not an uncommon verb, and does not necessarily bear any relationship to dreams. A more elegant and simple solution is to accept the sentence for what it says – the passage refers to magic as being a boon of the gods, and affirms that magic can function in the day and the night.

Thus far, we have found no reference to dream interpretation prior to the New Kingdom. It is entirely possible that future excavations in the field or searches within existing museums or private collections may yield such texts. But based on the currently known evidence, it is also reasonable to suggest that the interpretation of dreams and the recording of dream books began only in the New Kingdom, possibly the Ramesside Period, perhaps as an adaptation from familiar texts such as the Calendars of Lucky and Unlucky Days.

The Dream Book and society

The interpretations of dreams found in dream books, both modern and ancient, rely on a relationship between the image seen and its interpretation. Such a relationship is usually based on linguistic devices (such as homophony, or puns), 69 or a contemporary cultural association. In ancient Egypt, punning was a particularly popular linguistic device, not because it was considered humorous or trivial, but because word play in general was an integral element in rituals. 70 The presence of word play throughout the Dream Book neither reflects any sort of contemptuous attitude on the part of the Egyptians, nor suggests that the text was a literary exercise. Hodge has noted that while the denigration of puns as the ‘lowest form of humour’ may be prevalent in modern Western culture, this was certainly not the case in the ancient Near East, where the root and pattern systems of the languages provide fertile fodder for the generation of puns. Recently, Loprieno has pointed out that word play encompassed not only the phonetic and the semantic spheres, but also the dimension of writing itself. 71 Indeed one form of writing, the hieroglyphic script, itself in some ways resembles the script of dreams from a Freudian perspective. 72 According to Freudian psychoanalysis, when interpreting elements of a dream one is unsure whether the relationship between the element and its latent meaning is based on similarity or contrast in meaning, a historical basis (such as a memory), symbolism, or assonance. 73 While plays on words are particularly prevalent in the hieroglyphic script, they can also be enjoyed in the hieratic script of the Dream Book, which contains the same range of bases for interpretation. In all cases, a familiarity with the Egyptian culture and writing system is required in order to disentangle these complex passages. For example, one passage tells us that ‘If a man sees himself in a dream sailing downstream; BAD,it means a life of running backward.’ In Egypt, the current runs downstream while the winds blow upstream, and thus one normally sails upstream. This point is visually clear, for the word for travelling downstream is usually determined by the sign of a boat without sails  while travelling upstream usually has a boat with sails .

while travelling upstream usually has a boat with sails . The image of going downstream with sails up runs counter to the norm – and the interpretation is thus of a life running backward.

The image of going downstream with sails up runs counter to the norm – and the interpretation is thus of a life running backward.

The use of paronomasia to create or expose connections pervades the Egyptian Dream Book, together with the related phenomena of metonymy and metaphor. In this we are thankful, for far from being meaningless linguistic toys, puns ‘represent a central component of the Egyptian analysis of the world, and remain a stable feature of Egyptian culture throughout its entire historical evolution. From the Pyramid Texts down to the Ptolemaic times they provide a linguistic instrument to classify the elements of life.’ 74 Without intending to, the Egyptians have left us a useful vehicle for exploring their world.

The significance of certain dreams could derive from other common divinatory schemes, such as the pairing of opposites, as seems to be the case in ‘If a man sees himself in a dream as dead; good, (it means that) a long life is before him’ (r. 4.13). Others rely on the interpreter being familiar with the uses or characteristics of the image seen in the dream. For example, figs were used as medicinal ingredients. If a man were to see a man eating figs it might be because he was having a medical problem. Thus one interpretation reads, ‘If a man sees himself in a dream eating sycamore figs; BAD, it means pains’ (r. 7.2). Other dreams seem to be based on myths, others on satire, others perhaps on proverbs. It is doubtful if any of the relationships were arbitrary, but without a deeper familiarity with the culture and everyday workings of ancient Egypt, most are likely to remain cryptic to us.

While the Dream Book could aid an Egyptian man to catch a glimpse of his future, and perhaps to guide his behaviour, it can also help the modern scholar to look in the opposite direction. Even when the connections between the dreams and their interpretation remain obscure, the content reflects the underlying social structure, cares, wishes, and even belief systems prevalent in the waking life of a certain class of Egyptian. As mentioned above, certain themes such as promotion, owning of property and households, writing, and the acquisition of wealth and prestige, suggest that the composition describes the dreams of townspeople, craftsmen, and scribes. 75 The concerns are not those of agricultural labourers nor those of royalty, but they are consistent with our current reconstructions of village life based on other types of evidence from Ramesside Deir el-Medina.

The Dream Book itself explicitly describes the dreams of at least two categories of individuals, for the final section begins with the heading: ‘BEGINNING OF THE DREAMS of the followers of Seth’ ḥ⫖.t-c ; m rsw.t jmy.w-ḫt Stḫ. This is immediately preceded by a description of the personality and physical characteristics of this type of man (r. 11.1–18). The first portion of the papyrus is missing, but it is possible that it too began with a description of a type of man, one quite different from the ‘follower of Seth’. It has been suggested that this other category would have been characterized as a ‘follower of Horus’ (šms.w Ḥr) – a group well attested since the Pyramid Texts. However, it should be noted that the phrase ‘follower of Horus’ does not actually appear in the surviving dream portion of the text. Unfortunately, the beginning of the description of the Sethian man is also missing and this section of the papyrus contains large lacunae, making it difficult to form an accurate portrait. What emerges from the scraps is a fragmentary sketch of a man with curly hair, possibly naturally red hair as is emphasized by mentions of his armpit hair, beard and eyebrows. He is described as a potentially violent, decadent, and debauched man and a womanizer. When he drinks (which he does often to excess), his Sethian nature takes control, and yet, he nevertheless enjoys a long life. The text tells us that he may be a member of the royal classes, but that his tastes and manners are unrefined, unrestrained and earthy, like those of a commoner. His solitary nature places him as a misfit outside the norms of ideal Egyptian society. But while he does not fulfil the image of the ideal as presented in the wisdom texts, being neither humble, peaceful, nor silent, he seems to represent a personality type one could expect to meet in ancient Egypt. 76 Indeed, glimpses of such individuals and conduct can be found in some of the letters and accounts from Deir el-Medina, as well as in the didactic texts, which contain injunctions against these types of behaviour.

It is unfortunate that only four dreams of the followers of Seth remain – too small a sample to form any firm conclusions. The very existence of these dreams implies that the Sethian man was considered as much a part of society as his counterpart – the follower of Horus. It also shows that men were thought to be divided into at least two distinct psychological types who saw different dreams and required separate interpretations. The implication is that not everyone has the same dreams, and that the dreams do not have the same meaning. This idea is expanded in the Demotic Dream Book, which includes a separate category for the dreams of women. 77 It should be noted that the images seen in the four dreams of the Sethian portion of the Ramesside Dream Book are not duplicated in the earlier section of the text, while the interpretations are lacking. All of these dreams seem to be good dreams, and we can conjecture that a series of good dreams would have been followed by a series of bad ones.

Description

The dream portion of P. Chester Beatty III is divided into three separate yet related sections. The first section consists of the visual images of dreams and their interpretations, the second is a spell to counter a bad dream, and the third begins with a description of the ‘followers of Seth’, followed again by their dreams and interpretations. The layout of the dream interpretations is the same whether they are found in the first section or in the last. 78

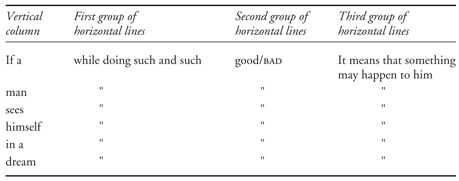

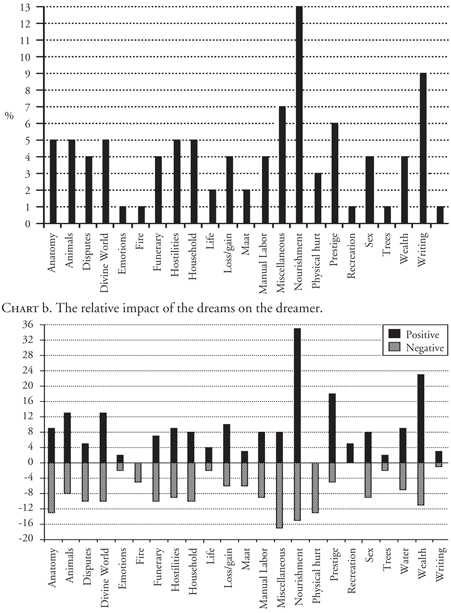

The charts below provide a brief summary of the content of the dreams listed in the Ramesside Dream Book. I have intentionally listed a wide range of categories; these can then be combined in various ways to form larger classes according to the interests of the reader. CHART a. shows the relative concerns of the dreamer, and CHART b. organizes these concerns according to their impact on the dreamer (negative or positive).

CHART a. The relative concerns of the dreamer

The miscellaneous category includes a number of unique examples such as seeing a wagon, the moon, prison, and other images. Evidently, nourishment (13%), wealth (9%), and prestige (6%), were of great concern to the villagers, as was the impact of the divine world (6%) on their lives. Emotions (1%), recreation (1%), and writing and reading (1%) played a much smaller role, as did sex (4%). Not surprisingly, disputes (4%) are generally assigned a negative impact, while prestige usually appears as a benefit.

The papyrus is damaged at the beginning, thus we have no way of knowing how many dreams would have been listed at the outset (there are at least 11 missing), and whether it included a description of men who were followers of Horus as has been suggested. 79 In the first section, the 139 dreams interpreted as good omens are listed first (r. 1.12–6.25), then 83 negative omens (r. 7.1–10.9). 80 This is followed immediately by a protective spell to ward off the effects of a bad dream (r. 10.10–19), until Amunnakht’s intrusive colophon takes up the rest of the column (r. 10.20–3). The description of the Sethian type of man is found in r. 11.1– 18, and a listing of four good dreams (r. 11.19–23) completes the legible portion of this Dream Book. 81

Grammatical note

Before presenting the text of the Ramesside Dream Book, a short grammatical note is in order. The palaeography of the text, as well as the orthography of certain words, appears to be Ramesside. The grammar is largely late Middle Egyptian, which would lend credence to the text’s authority and is an entirely appropriate choice for the genre, even if it were composed in the New Kingdom. 82 In an effort to facilitate a smooth reading, I have generally rendered the prospective with ‘will’, with the understanding that this was a modal future in the original. This applies as well to the Egyptian infinitive constructions for which English lacks an elegant literal translation. The 227 dreams and their interpretations could tell us much about Egyptian society, yet the following should be considered as a possible reconstruction and an invitation to further study.

THE RAMESSIDE DREAM BOOK

Gardiner, A.H. 1935. Hieratic Papyri in the British Museum, Third Series: Chester Beatty Gift. Vol. I, Text. London, British Museum. NK/Ramesside(?) – Written near the end of the reign of Ramesses II/ Library of Qenherkhopshef in Deir el-Medina.

On the papyrus, each interpretation begins with jr m⫖⫖ sw s m rsw.t written vertically in columns. A literal translation of this phrase, ‘if a man sees himself in a dream’, implies that the dreamer is watching himself in the dream, but this is not the sense of the phrase. I will therefore translate ‘if a man sees in a dream’, in those cases when this is a clearer reflection of the meaning of the phrase. I have also tried to retain the essence of word-plays whenever possible. The dream interpretations were written in horizontal rows perpendicular to this column, consisting of the antecedent, then an evaluation of the dream image as ‘good’ nfr or ‘BAD’ D̲W, followed by the consequent. Throughout these translations rubric (words or phrases which were written in red in the original) are indicated by the use of CAPS (for example the word ‘bad’ was consistently written in red).

RECTO 1

First 11 lines missing

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good,...]

(r. 1.12)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, it means giving [...] in his hand.

(r. 1.13)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good], it means [...]

(r. 1.14)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good,...]

(r. 1.15)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good,...] which will happen to him.

(r. 1.16)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good], it means [...] his [dream?].

(r. 1.17)

Gardiner suggests that the consequent may read ‘...it means [the fulfilment

of] his [dream?]’ based on the determinative  which appears before the =f. 83

which appears before the =f. 83

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good], it means [...by] his god.

(r. 1.18)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good], it means [he?...] something.

(r. 1.19)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, it means a precious thing.

(r. 1.20)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, it means that he will be prosperous.

(r. 1.21)

Literally, wḏ⫖ ḫt=f pw means ‘he is prosperous of things’.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, it means sustenance.

(r. 1.22)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, it means something [with which] he will fill [the mouth?]. 84

(r. 1.23)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

good, (it means that) sickness will be removed from him.

(r. 1.24)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good,.]

(r. 1.25)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[good,.]

(r. 1.26)

RECTO 2

If a man sees himself in a dream when his mouth is broken (sd.t);good, it means that as for something which is terrifying in his heart, god will break(sd) it open.

(r. 2.1)

Note the word play here with sd (break). In Pyr. §249, fear occurs in the same context as sd: ‘O [Osiris the King], here is this Eye [of Horus]; [take] it, that you may be strong and that he may fear you – break the red jars’. This passage is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream eating the fruit of tiger nuts (bnr.w nt wc ḥ); good, (it means) the governing of his townspeople.

(r. 2.2)

Gardiner85 identifies wc ḥ with the carob bean. However, Hannig86 identifies wc ḥ as Cyperus esculentus (Cyperus grass). According to Brewer87 the existence of carob trees in ancient Egypt is by no means certain. Cyperus grass produces pea-sized edible tubers now commonly called ‘tiger nuts’ which may be candidates for bnr.w nt wc ḥ. According to Ikram, 88 these have been found in tombs and in the stomachs of mummies from the Pre-Dynastic Period. They are also included in J.F. Nunn’s compilation of herbal remedies. 89

The concept of governing townspeople included ensuring that they were provided with adequate provisions, perhaps represented by the tiger nuts.

If a man sees in a dream a crane (ḏ⫖.t);

good, it means prosperity (wḏ⫖).

(r. 2.3)

This couplet features a wordplay between ḏ⫖.t (crane) and wḏ⫖ (prosperity).

If a man sees in a dream a honey jar whose top has been covered;

good, it means [...] him something by his god.

(r. 2.4)

The lacuna could be reconstructed with c fn, thus reading ‘covering him something by his god’. For the divine significance of honey see Chapter 5. Janssen calculates ‘the average price of honey seems to have been c. 1 deben per hin’, 90 which indicates that it was relatively inexpensive.

If a man sees himself in a dream with his townsfolk encircling (phr) him;

good, it means [...].

(r. 2.5)

Ritner91 proposes that phr may refer to ritual circumambulation, while allowing that this example is unclear.

If a man sees himself in a dream chewing lotus-leaves (jnḥ⫖s);

good, it means something which he will enjoy.

(r. 2.6)

The word jnḥ⫖s92 appears in medical texts in Admonitions 15,12. 93 Scenes of lotuses and blue water lilies are a common feature of paintings and reliefs. They are prominently featured in New Kingdom tomb paintings of funerary banquets, where both men and women wear garlands of lilies and hold the blossoms to their noses. While the precise nature of their symbolism is much debated, there is no doubt that they seem to be associated with pleasure.

If a man sees himself in a dream shooting at a target;

good, it means something (good) that is going to happen to him.

(r. 2.7)

If a man sees in a dream giving him copper (ḥmtj) as [...];

[good], it means something at which he will be exalted.

(r. 2.8)

Copper was not an inexpensive material, and owning copper tools would have indicated some status. The following passage also contains two instances of ḥm, thus there is a homophonous play on these words spanning the two passages.

If a man sees in a dream [...] his woman (ḥm.t=f to a married man;

[good], it means that the bad things (ḏw.t) related to him will retreat (ḥm).

(r. 2.9)

Note the homophony with ḥm.t and ḥm (this could also be ḥm-ḫt).The dw.t appear again in the Invocation to Isis (which is discussed later in this text), where they are ‘driven out’ of the sleeper. The woman in this example is called ḥm.t=f (see also r. 2.9, 6.12, 7.25, 9.1, 9.25) while in other passages the woman is referred to simply as s.t ḥm.t (r. 3.16, 7.17, 9.9). To differentiate the two, I translate ḥm.t=f as ‘his wife’ and s.t ḥm.t as ’a woman’.

If a man sees in a dream [...] his [...];

good, [...] great.

(r. 2.10)

If a man sees himself in a dream after his penis has enlarged;

good, it means an increase of his possessions.

(r. 2.11)

The relationship between image and meaning seems clear here.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]ing a bow in [his] hand;

[good], (it means that) he will be given an important office.

(r. 2.12)

The bow could mean gaining prestige through military accomplisḥments. The bow could also represent hunting – an activity associated with the elite and royalty.

If a man sees himself in a dream dying from a back wound(?) (ḏ⫖y);

good, it means living after ‹his› father [dies(?)].

(r. 2.13)

If Gardiner is correct in the restoration, then there is a play on contrary notions of living and dying. 94 Living on after his father dies is of course positive both for the son and his father, who then is assured of funeral rites being continued.

The word ḏ⫖y does not appear in the dictionary with this orthography  The same determinative appears in a twentieth-dynasty example in an unclear context in a text from Medinet Habu (Med. Habu 46, 28 Year 8). 95 Gardiner suggests war wounds.

The same determinative appears in a twentieth-dynasty example in an unclear context in a text from Medinet Habu (Med. Habu 46, 28 Year 8). 95 Gardiner suggests war wounds.

If a man sees in a dream the god who is above;

good, it means a great meal.

(r. 2.14)

This passage is discussed further in Chapter 5.

If a man sees in a dream a snake (s⫖-t⫖) [...];

good, it means a [...] meal.

(r. 2.15)

With the lacunae it is difficult to see the connection between the image and its interpretation. s⫖-t⫖ refers to a serpent of some kind. Mercer describes it as the ‘son of Geb’ (according to Pyr. 689d), and ’according to 691a–b, the same serpent was brother of Osiris, therefore uncle of Horus; and as uncle of Horus he may have been identified with Set’. 96 However, the first text (Pyr. 689d) does not explicitly mention Geb, nor is the s⫖-t⫖ determined with a divine sign. In the second instance, 691b reads s⫖w ṯw jt=k wtt wsjr s⫖-t⫖ s⫖w ṯw nb(?), ‘Beware of your father, whom Osiris begot; O s⫖-t⫖-snake beware of the...!’ This would make Osiris his grandfather, and presumably the one whom Osiris begot was Horus. This would make s⫖-t⫖ a son of Horus. One could also translate ‘one whom Osiris begot’ as referring to s⫖-t⫖ himself. But this would make him a brother of Horus.

The snake also appears in Coffin Text Utterance 885 which is a spell for warding off snakes. The sections in question are VII 97(s) ‘O Shu, the earth is against you; the son-of-earth-snake is against you.’ He appears also in VII 98(i) ‘Fall, O son-of-the-earth-snake, on [your] back(?).’ A ‘meal’ is mentioned between these two instances.

The s⫖-t⫖-snake appears in Book of the Dead spell 87 where he is depicted as a snake with two legs. 97 The text reads ‘SPELL FOR ASSUMING THE FORM OF A SON OF EARTH. TO BE SAID BY N.: I am a son of earth, long of years, who sleeps and is (re)born every day. I am a son of earth dwelling in the realm of the earth I sleep and am (re)born, renewed, rejuvenated every day.’

Because s⫖-t⫖ is a type of other-worldly snake, there may be a semantic pun with his form of ḥf⫖w (snake), and df⫖w (the meal). On another level, the connection may be that the s⫖-t⫖ snake, like the nṯr, inhabits the farworld, and is therefore a good omen.

If a man sees himself in a dream when entering his [……];

good, [it means that] disputes will be dismantled.

(r. 2.16)

If a man sees himself in a dream drinking [……] beer;

good, it means a surging (nḏ⫖ḏ⫖) of his emotions (nj ib).

(r. 2.17)

Gardiner suggests that a semantic pun may be at work here for the verb nḏ⫖ḏ⫖ appears in P. Ebers as a liver or lung disease. 98 He cites examples where one of the medicaments used to treat the latter is nḏ⫖ḏ⫖.yt beer, which he suggests could be restored in the lacuna in the protasis.

However, Walker cites P. Ebers 188 as ‘then you should say, "His liver is clean (i.e. healed) it is in nḏ⫖ḏ⫖-condition, he has taken up the medicine" ’. 99 The condition seems more properly to be a positive one, which explains the positive dream diagnosis. There is a tendency for people to become quite emotional when using intoxicants, and perhaps nḏ⫖ḏ3 nj jb here simply indicates an outpouring of emotion.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...];

good, (it means that) great feasting is going to happen to him.

(r. 2.18)

If a man sees himself in a dream reducing(?) [...];

good, it means reducing [...] desire(?) [...]

(r. 2.19)

Gardiner suggests ḫb.t ‘reducing’ for the antecedent. 100 Other possibilities include ḫbj ‘dancing’, ḫb⫖ ‘ravaging’, ḫbs ‘hack up’, all of which provide a wordplay.

If a man sees himself in a dream his mouth full with earth;

good, (it means) eating (off) his fellow citizens.

(r. 2.20)

Note the play on the mouth being full and eating. There is the possibility that this is to be read ‘his fellow citizens may eat’, but this seems to be rather too altruistic.

If a man sees himself in a dream consuming the flesh of a donkey (c ⫖);

good, it means that he will become great (sc ⫖).

(r. 2.21)

There is an obvious pun here between sc ⫖ and sc ⫖.

If a man sees himself in a dream consuming the flesh of a crocodile;

good, it means consuming the possessions of an official.

(r. 2.22)

Gardiner points out the play on the greediness of the official and the greediness of the crocodile with which the official is often compared. 101 Notice that crocodiles and officials are associated again here, as well as in r. 5.11 and r. 5.17 (with an identical antecedent).

If a man sees himself in a dream upon a sycamore tree (nḥ⫖.t) which is flourishing;

good, it means that he will lose (nhy) [...].

(r. 2.23)

Note the possible pun between nh3.t and nhy. 102 A similar antecedent appears in r. 4.7. Notice the tree in question is the sycamore, which has strong religious connotations. Being up high on trees seems to be good in general (see r. 3.9; 4.7; 4.11).

If a man sees himself in a dream looking (nw) through a window;

good, (it means that) his call will be heard by his god.

(r. 2.24)

The word nw is used here in contrast with m⫖⫖ which appears throughout this text. The composer may have selected this marked term over the more common one in order to emphasize the contrast between the act of consciously ‘looking’ at something, and involuntarily ‘seeing’ something. 103

If a man sees himself in a dream when a homage present (mnḥ.t) is given to him; good, it means that his call will be heard.

(r. 2.25)

There is no obvious pun here, but perhaps the simple matter of the unlikely situation of being given a gift usually reserved for leaders, increases the potential that someone, perhaps a god or the king – though it is not stated specifically – will pay attention to the dreamer (see Chapter 5).

If a man sees himself in a dream upon a roof;

good, it means that something will be found.

(r. 2.26)

Two explanations seem plausible here. The first is quite simply that a person who is on a roof can see farther and is more likely to find things. The other is that there may be a religious connotation to the ‘finding’. Note that r. 2.24 is clearly a pious reference, while similar terminology is used in r. 2.25. If the dreamer sees himself on top of a house or temple, he is obviously closer to the sky, and thus to god. Assmann has suggested that ‘finding’ (gm) can be used as a technical term to indicate a revelation by god. 104

RECTO 3

If a man sees himself in a dream [...] a pond(?);

good, it means that the road will be partial (gs⫖) towards him.

(r. 3.1)

Note the pun with g(⫖)s in the following line 3.2. In 3.1 perhaps gs⫖, literally ‘tilt’, may indicate that the road may always be favourabletowards the dreamer.

If a man sees himself in a dream (in) mourning (g⫖s);

good, (it means) the multiplying of his possessions.

(r. 3.2)

The lexeme g⫖s is apparently attested from the New Kingdom onwards (P. Orbiney 8,8), which offers further evidence for a later date for this text. 105 Likely the connection between mourning and an increase in possessions is the possibility of an inheritance.

If a man sees himself in a dream after his hair has lengthened;

good, it means something at which his face will brighten.

(r. 3.3)

The determinative for ‘mourning’ seen in r. 3.2 is the three locks of hair (D3), perhaps indicating a specific appearance of hair during mourning. Funerary scenes often depict women with long hair thrown over their face, while Akhenaten is unshaved while mourning the death of his daughter. In r. 3.3 the hair has grown out. There may be a connection between this couplet and the previous one, in that the hair has now lengthened after mourning.

(D3), perhaps indicating a specific appearance of hair during mourning. Funerary scenes often depict women with long hair thrown over their face, while Akhenaten is unshaved while mourning the death of his daughter. In r. 3.3 the hair has grown out. There may be a connection between this couplet and the previous one, in that the hair has now lengthened after mourning.

If a man sees in a dream white-bread (t-ḥḏ) being given106 to him;

good, it means something at which his face will brighten (ḥḏ).

(r. 3.4)

Note that the consequent of this couplet and the preceding are identical. Note the pun of t-ḥḏ (white-bread) with ḥd (brighten/whiten).

If a man sees himself in a dream drinking wine;

good, it means living according to maat.

(r. 3.5)

See the identical antecedent in r. 4.4 where the interpretation is ‘opening his mouth to speak’.

If a man sees himself in a dream sailing downstream;

good, (it means) tying his [ ].

(r. 3.6)

The identical image of sailing downstream appears in the antecedent of r. 8.3 and r. 10.1 (in the latter case the dream is interpreted as bad).

If a man sees himself in a dream copulating with his mother who is issuing fluid(?);

good, (it means that) he will be joined by his clansmen. 107

(r. 3.7)

The image of an intimate relation here represents a closer relationship between a man and his fellows.

If a man sees himself in a dream copulating with his sister (sn.t=f);

good, it means that something will be assigned to him.

(r. 3.8)

The word sn.t in Egyptian can refer to a person’s biological sister, lover, aunt, or a close friend.

If a man sees himself in a dream upon a dom-palm;

good, it means a joy in the conduct of his ka.

(r. 3.9)

Gardiner translates as ‘what his k⫖ had done’. Being up high on trees seems to be good in general (see r. 2.23; 4.7; 4.11). 108

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]ing of high/uplifted fingers;

good, something will be provided to him by his god.

(r. 3.10)

The religious significance of this passage is discussed in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream while people [...]ing him with a blow;

good, it means that something [...] to him.

(r. 3.11)

If a man sees himself in a dream with a four-legged animal (šsr) with him; good, establishing him(?) [...] his heart.

(r. 3.12)

The word šsr may refer to an ’ape’. 109 A short sequence featuring the dreamer seeing various animals follows.

If a man sees himself in a dream seeing a dead bull;

good, it means seeing [...] his enemies.

(r. 3.13)

A pun occurs with seeing (m⫖⫖) in both parts of the couplet. The connection between an enemy and the dead bull is unclear, unless perhaps mt or something like ‘death’ of his enemy fits in the lacuna. Note that the connection of a bull with an enemy reappears in r. 4.8 and r. 4.16.

If a man sees himself in a dream seeing [...];

good, his [...] overthrow [...]

(r. 3.14)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]? a man [...] send far(?) (ḥ⫖b c ⫖);

good, great [...] his(?)[...]

(r. 3.15)

The ḥ⫖b c ⫖ in the dream image could possibly mean a ‘great message’. If a man sees himself in a dream [...] a woman [...];

good, [...] against a wife by [her(?)] husband [...]

(r. 3.16)

If a man sees himself in a dream being given a head;

good, (it means that) his [mouth will be opened] in order to speak.

(r. 3.17)

The connection here may simply be the mouth being a part of the head. The same interpretation but with a different protasis appears in r. 4.4.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]

[...]

(r. 3.18)

If a man sees himself in a dream binding(?) [...] a donkey;

[...]

(r. 3.19)

If a man sees himself in a dream being very discreet;

[...]

(r. 3.20)

If a man sees himself in a dream going forth [on(?)] the earth (with(?)) a leg [...]; [...]

(r. 3.21)

If a man sees himself in a dream [after he was given………]; [...]

(r. 3.22)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...];

[...]

(r. 3.23)

If a man sees himself in a dream copulating [...];

[...]

(r. 3.24)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...]; [...]

(r. 3.25)

RECTO 4

If a man sees himself in a dream [k]illing (sm⫖) a snake;

good, (it means that) disputes [...] will be killed (sm⫖).

(r. 4.1)

The use of sm⫖ (‘kill’) creates the link between the image and its interpretation.

If a man sees in a dream his face (hr=f as a panther;

good, (it means) acting (as) a chief (ḥry-tp).

(r. 4.2)

The wearing of leopard or panther pelts often signals prestige, and this is perhaps referred to here. There is also a play on hr=f and ḥry-tp.

If a man sees in a dream a large (c ⫖) cat;

good, it means that a large (c ⫖) harvest is going to come to him.

(r. 4.3)

On the surface, this seems to be a simple play on mjw-c ⫖ and šmw-c ⫖. In addition, seeing a large cat may imply a lack of grain-eating rats therefore a large harvest. Equally likely is that this is a reference to the Great Cat, who in glosses in both Coffin Text Utterance 335 and Book of the Dead 17 is described as being the god Ra.

If a man sees himself in a dream drinking wine ([s]wj jrp);

good, (it means that) his mouth will be opened (wpj r⫖) in order to speak.

(r. 4.4)

Gardiner points out that this is the same antecedent as r. 3.5. There, however, drinking wine meant living in maat. He also points out the parallel in Pyr. §92 (PT 153) ‘O Osiris the king, your mouth is split open by means of it – 2 bowls of Lower Egyptian wine.’ 110 Thus there seem to be three levels of word-play at work here. The first is the connection between opening the mouth and wine, the second may simply be that drinking wine is commonly known to loosen the tongue, and the third is the assonance of swj jrp with wpj r⫖. Finally, the interpretation could also be a reference to the Opening of the Mouth ritual.

The same interpretation appears in r. 3.17.

If a man sees himself in a dream binding wretched people in the night;

good, (it means that) speech will be taken away from his enemies.

(r. 4.5)

Groll cites this as an example where ‘the visual image of the dream corresponds to an idea which can be immediately expressed in words’. 111 An alternative translation is ‘binding the people who are netted/trapped in the night’. Taking away a person’s ability to speak is a powerful threat, for without this ability, one cannot speak the necessary words to safely get through the farworld.

If a man sees himself in a dream ferrying in a ferry-boat; 112

good, it means the going forth of all disputes.

(r. 4.6)

This dream features a metaphor using the visual image of ferrying for the idea of going forth. In addition, the last three dream interpretations all involved speech or md.t.

If a man sees himself in a dream sitting on a sycamore tree;

good, (it means that) all his badness will be driven out.

(r. 4.7)

A similar dream image appears in 2.23. The sycamore is a sacred tree and Pyr. §916 mentions gods sitting on this tree, ‘The High Mounds will pass me on to the Mounds of Seth, to yonder tall sycamore in the east of the sky, quivering (of leaves)(?), on which the gods sit...’ The sycamore is also mentioned in Pyr. §689 along with s⫖-t⫖ snake. Pyr. §1433 brings together the preceding ferry boat of r. 4.6, and the sycamore of r. 4.7: ‘This King has grasped for himself the two sycamores which are in yonder side of the sky: "Ferry me over!" And they set him on yonder eastern side of the sky.’ The positive image of being high up on trees also appears in r. 2.23, r. 3.9 and r. 4.11.

If a man sees himself in a dream killing a bull;

good, (it means that) his enemies will be killed.

(r. 4.8)

Note the similar connection of a bull with an enemy in

r. 3.13.

If a man sees in a dream Busiris;

good, (it means that) great old age will be achieved.

(r. 4.9)

If one sees Busiris, that is the place of Osiris, one lives to an old age.

If a man sees himself in a dream mixing dates;

good, it means that victuals will be found.

(r. 4.10)

If a man sees himself in a dream climbing up a mast;

good, (it means that) he will be elevated by his god.

(r. 4.11)

The association here seems to be based on the visual imagery of being high up on a mast, and being lifted up high by a god. Being up high on masts as well as trees is a positive image (see r. 2.23; 3.9; 4.7). This passage is discussed further in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream tearing his clothes;

good, (it means that) he will be freed from all badness.

(r. 4.12)

Note that the image of the removal of clothes indicates the removal of wrongs.

If a man sees himself in a dream dead;

good, (it means) a long life is before him.

(r. 4.13)

This is an example of a dream where the interpretation is the opposite of the image.

(r. 4.14)

If a man sees himself in a dream binding his legs to himself; good, (it means) dwelling with his fellow citizens.

The identical interpretation appears in r. 4.23.

(r. 4.15)

be positive

If a man sees himself in a dream falling off a wall; good, it means the outcome of a quarrel.

It is quite interesting that the dream of falling is considered to (see also r. 5.24).

If a man sees himself in a dream cutting up a bull with his own hand;

good, (it means that) his (own) opponent will be killed.

(r. 4.16)

This is another dream indicating a connection between a bull and an enemy (see r. 3.13, 4.8). Volten read the bovine sign as jḥ, and suggested a pun with c ḥ⫖ (opponent). 113

If a man sees himself in a dream fetching jars (jn ḥn.w) out of the water;

good, (it means that) a life of abundance (n-ḥ⫖w) will be found in his house.

(r. 4.17)

Gardiner points out the pun jn hn.w with n-ḥ⫖w. 114

If a man sees himself in a dream writing upon a [palette(?)];

good, (it means that) a man will be established in his office.

(r. 4.18)

The interpretation suggests a connection between literacy and an office (see also r. 6.10.) Note that in r. 7.21 writing on papyrus is a negative omen, whereas writing on a palette is considered positive.

If a man sees in a dream herbs of the field;

good, (it means that) sustenance will be found for (his) father (jt).

(r. 4.19)

The herbs may possibly hint at a reference to funerary offerings. Perhaps in this case, as in the previous one with ‘father’ jt (r. 2.13), the lack of possessive pronoun indicates this is to mean ’ancestor’ in general. Note that this is one of a series dealing with produce (r. 4.19–22).

If a man sees himself in a dream taking dates; good, it means that victuals will be found as a gift of his god.

(r. 4.20)

For a discussion on the relevance of this passage to the issue of religion see Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream ploughing emmer in a field;

good, (it means that)...something [to(?) him(?)] in(?) [...]

(r. 4.21)

If a man sees himself in a dream giving himself victuals of the temple;

good, (it means that) life will be assigned to him by his god.

(r. 4.22)

Further discussion on this passage can be found in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream sailing in a boat; good, it means dwelling with his fellow citizens.

(r. 4.23)

The identical interpretation appears in 4.14, but the connection the dream and interpretation remains opaque in this case.

If a man sees himself in a dream [ ]ing bones(?);

good, (it means) sustenance of the palacel.p.h. will be found.

(r. 4.24)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...];

good, (it means) [...] will assign to him [...]

(r. 4.25)

Perhaps the first lacuna in the consequent could be restored ‘his god’ ntr=f, thus ‘(it means that) [his god] will assign to him’. Gardiner suggests ‘his

father’ jt=f. 115

RECTO 5

If a man sees himself in a dream [...] in the field;

good, (it means) giving to him [...]

(r. 5.1)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...] river;

good, (it means that) his call will be heard by his god.

(r. 5.2)

This passage is discussed in relationship to expressions of personal piety in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...] blood(?);

good, (it means that) an end will be brought to his enemies.

(r. 5.3)

If a man sees himself in a dream [ ] milk;

good, (it means that) much food is going to come to him.

(r. 5.4)

If a man sees himself in a dream [drinking(?)] 116 his urine;

good, (it means that) something belonging to his daughter will be consumed.

(r. 5.5)

This is the last in a series of dreams involving liquids: river, blood, milk, and urine.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...] him silver and gold;

good, (it means) much food of the palacel.p.h.

(r. 5.6)

Silver and gold would normally be associated with royalty, and thus the connection to the palace. This is the same interpretation as r. 5.10 and 5.12

If a man sees himself in a dream [...-ing(?) stone(?)] against his finger;

good, it means giving to him his cattle.

(r. 5.7)

If a man sees himself in a dream [...-ing sto]ne;

good, it means giving something to him.

(r. 5.8)

Stone is mentioned again in r. 6.4 with a positive interpretation and in r. 8.18 with a negative meaning.

If a man sees himself in a dream [reading from] a papyrus roll;

good, (it means that) a man will be established in his home.

(r. 5.9)

If a man sees himself in a dream cutting up a female hippopotamus;

good, (it means) much food of the palace l.p.h117

(r. 5.10)

This has the same interpretation as r. 5.6 and r. 5.12.

The feminine ending ‘t’ is quite clear in the hieratic so the reading as female hippopotamus is certain. If it were the male hippopotamus it could possibly represent Seth, and the dreamer would be performing a symbolic act usually reserved for the king. The female hippopotamus, however, is usually associated with Taweret, and thus is naturally a good omen, but in this context the image of cutting her up seems inappropriate. In general, the female hippopotamus represented a good and helpful deity, and was not associated with Seth as was her male counterpart. 118 Hippopotami had been hunted for food and meat, but this practice was likely restricted to an earlier time in Egypt’s history.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...-ing] crocodiles;

good, it means acting as an [official].

(r. 5.11)

It seems likely that Gardiner is correct in interpreting this as the common comparison between an ’assertive’ official and a crocodile. 119 Note that crocodiles and officials are associated again in r. 2.22 and 5.17.

If a man sees himself in a dream [...];

good, (it means that) food of the palacel.p.h. will be consumed.

(r. 5.12)

This is the same consequent as r. 5.5 and 5.10. This is the last in a series of three dream images of animals: female hippopotamus, crocodile, and a third animal (assuming Gardiner’s estimation of the badly damaged lacuna is correct.)

If a man sees himself in a dream sitting in a garden of sunlight;

good, it means pleasure.

(r. 5.13)

If a man sees himself in a dream removing a wall;

good, it means purification [...] from badness.

(r. 5.14)

If a man sees himself in a dream [eating(?)] faeces;

good, (it means that) his possessions in his house will be consumed.

(r. 5.15)

There is a lacuna in the precise spot of the verb in the antecedent, where Gardiner sees the verb ‘eat’ (wnm). In spells and religious texts this is invariably the vilest of acts, reserved for the unjustified dead.

If a man sees himself in a dream breeding with a cow;

good, it means that a happy day will be spent in his house.

(r. 5.16)

Parlebas translates this as ‘If a man sees himself making love with a cow, that signifies a day of love at his house.’ 120 His suggestion that the connection here is based on the cow being a representative of Hathor – who is the goddess of love, joy, and happiness – seems reasonable.

If a man sees himself in a dream consuming the flesh of a crocodile;

good, (it means) acting as an official among his people.

(r. 5.17)

Notice that crocodiles and officials are associated again as in r. 2.22 (with an identical antecedent) and in r. 5.11.

If a man sees himself in a dream paddling(?) water(?);

good, it means prosperity.

(r. 5.18)

If a man sees himself in a dream immersing in the river;

good, it means being purified from all badness.

(r. 5.19)

Parlebas suggests a connection between the regenerative powers of the primordial river as mentioned in religious texts and this image. 121

If a man sees himself in a dream lying down upon the floor; good, (it means that) something of his will be consumed.

(r. 5.20)

Groll suggests that this implies ‘being self-supporting’. 122

If a man sees in a dream tiger nuts (wc ḥ); good, (it means that) a happy life will be found.

(r. 5.21)

See r. 2.2 above for a discussion on the meaning of wc ḥ. The reputed aphrodisiac qualities of the Cyperus tubers 123 may explain the connection to a happy life.

If a man sees himself in a dream seeing the moon when it is shining;

good, (it means) being clement to him by his god.

(r. 5.22)

The clemency of a god is triggered by the image of the risen moon, itself an icon of a number of gods including Thoth, Osiris, Khonsu, as well as one of the eyes of Horus. See Chapter 5 for further discussion of this passage.

If a man sees himself in a dream veiling (c fn) himself [...] (?); 124

good, (it means that) he will drive away his enemies from before him.

(r. 5.23)

Perhaps there is a connection with the idea that if an individual is veiled, he cannot see well, and his enemies will be driven to where he cannot see them. The verb c fn is also used in situations where somebody is masked and thus unable to cast an evil eye. The idea of the dreamer being veiled in this situation, may be comparable to one in an omina-calendar cited by Vernus where the veil protects the wearer from possible effects of an evil- eye, and is thus a positive omen. 125

If a man sees himself in a dream falling [...];

good, it means prosperity.

(r. 5.24)

The unfortunate lacuna prevents us from knowing any details of this image, but it seems to be a dream of falling, which is commonly described in modern times, but here with a positive interpretation (see also r. 4.15).

If a man sees himself in a dream sawing wood [...];

good, (it means that) his enemies are dead.

(r. 5.25)

RECTO 6

If a man sees himself in a dream burying an old man;

good, it means prosperity.

(r. 6.1)

As part of his social duty the eldest son is supposed to perform the funerary ritual for his father, thus the image of burying an old man may indicate the fulfilling of social obligation and an inheritance.

If a man sees himself in a dream cultivating herbs;

good, it means that victuals will be found.

(r. 6.2)

There is a direct relationship here with the image of herbs resulting in the discovery of food.

If a man sees himself in a dream causing the cattle to come in;

good, (it means that) people will be assembled for him by his god.

(r. 6.3)

This passage may play on the concept of people (rmṯ) as the cattle (j⫖w.t) of god, a common theme in Egyptian religious discourse. 126 This dream is also discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream working stone in his house;

good, (it means that) a man will be established in his house.

(r. 6.4)

Stone is a lasting material, and is used for objects one wants to have well established. Stone is mentioned in r. 5.8 with a positive interpretation and in r. 8.18 as negative.

This is also the second example where the consequent refers to ’a man’ s (see r. 4.18).

If a man sees himself in a dream throwing his clothes on the ground;

good, it means the outcome of a dispute.

(r. 6.5)

If a man sees himself in a dream towing a boat;

good, (it means that) he will be landed well in his house.

(r. 6.6)

If a man sees himself in a dream threshing grain upon the threshing floor;

good, (it means) giving him life in his house.

(r. 6.7)

If a man sees himself in a dream eating grapes;

good, (it means) giving him something of his very own.

(r. 6.8)

Grapes are associated with wine and would, not surprisingly, be considered a positive sign.

If a man sees himself in a dream planting gourds;

good, (it means that) a good life will be given to him as his god’s gift.

(r. 6.9)

Gardiner derives bnd.t meaning ‘gourd’ from Coptic  127 For a detailed discussion of this passage see Chapter 5.

127 For a detailed discussion of this passage see Chapter 5.

If a man sees himself in a dream writing on a [fresh(?) papyrus(?)...];

good, (it means that) he will see his life as good.

(r. 6.10)

For another passage interpreting an image related to literacy as positive, see r. 7.22.

If a man sees himself in a dream burying [...] alive;

good, it means a lively prosperity.

(r. 6.11)

If a man sees himself in a dream breaking into [...];

good, (it means) giving to him his wife.

(r. 6.12)

If a man sees himself in a dream binding [...];

good, (it means) giving him his house in the end.

(r. 6.13)

If a man sees himself in a dream seeing a lily(?) blossom (ḥq⫖y[.t]);

good, (it means) prosperity.

(r. 6.14)

The word  is a hapax legomenon and the species of plant this refers to is unknown. The reading of the determinative is uncertain, and the lily blossom is based on Gardiner’s interpretation. 128

is a hapax legomenon and the species of plant this refers to is unknown. The reading of the determinative is uncertain, and the lily blossom is based on Gardiner’s interpretation. 128

There is a connection created between this and the following two passages by means of punning in the antecedents (ḥq⫖y[.t] and ḥ⫖q).

If a man sees himself in a dream plundering (ḥ⫖q) [...];

good, it means something with which he will be satisfied.

(r. 6.15)

If a man sees himself in a dream eating [...];

good, it means that food is going to come to him.

(r. 6.16)