Establishing Tricks with Lower Honor Cards

When you don’t have the ace in a suit, you’re in bad shape as far as sure tricks are concerned (see Book 5, Chapter 2 for more about sure tricks). Not to worry. Your new friend, establishing tricks, can see you through the tough times and help you win extra tricks you may need to make your contract. Check out the following sections for surefire techniques on establishing tricks.

Establishing tricks is about sacrificing one of your honor cards to drive out one of your opponents’ higher honor cards. You can then swoop in with your remaining honor cards and take a bundle of tricks.

In case you’re wondering, your opponents don’t just sit around and admire your dazzling technique of establishing tricks. No, they’re busy trying to establish tricks of their own. In Bridge, turnabout is fair play. Whatever you can do, your opponents can also do. Many a hand turns into a race for tricks. To win the race, you must establish your tricks earlier rather than later. Remembering this rule will keep you focused and help you edge out your opponents.

In case you’re wondering, your opponents don’t just sit around and admire your dazzling technique of establishing tricks. No, they’re busy trying to establish tricks of their own. In Bridge, turnabout is fair play. Whatever you can do, your opponents can also do. Many a hand turns into a race for tricks. To win the race, you must establish your tricks earlier rather than later. Remembering this rule will keep you focused and help you edge out your opponents.

Driving the opponents’ ace out of its hole

The all-powerful ace wins a trick for you every time. But no matter how hard you pray for aces, sometimes you just don’t get any, and you can’t count any sure tricks in a suit with no aces. Sometimes you get tons of honor cards but no ace, and you still can’t count even one sure trick in that suit. Ah, the inhumanity!

Cheer up — you can still create winning tricks in such a suit. When you have a number of equal honors in a suit but not the ace, you can attack that suit early and drive out the ace from your opponent’s hand. Here’s what you do:

-

Lead the highest honor card in the suit in which you’re missing the ace.

To get rid of the ace when you have a number of equal honors, lead the highest honor. So if you have the KQJ6, lead the king to drive out the ace. If they don’t take the trick with the ace, play the queen. One way or another you must take two tricks with the KQJ. If you lead a low card, like the 6, 7, or 8, your opponents won’t have to play the ace to take the trick. They can simply take the trick with a lower card, such as the 9 or 10, and they still have the ace! Not good.

When you have equal honors in your hand (where they can’t be seen), such as the KQJ, and want to lead one, use the higher or highest equal to do your dirty work. It is more deceptive. Trust us.

When you have equal honors in your hand (where they can’t be seen), such as the KQJ, and want to lead one, use the higher or highest equal to do your dirty work. It is more deceptive. Trust us.

If the equal honors are in the dummy where everyone can see them, you have the option of which one to play. It doesn’t matter, but to be uniform in this book, we have you play the lower or lowest equal.

- Continue playing the suit until your opponents play the ace and take the trick.

- After that ace is out of the way, you can count your remaining equal honor cards as sure tricks.

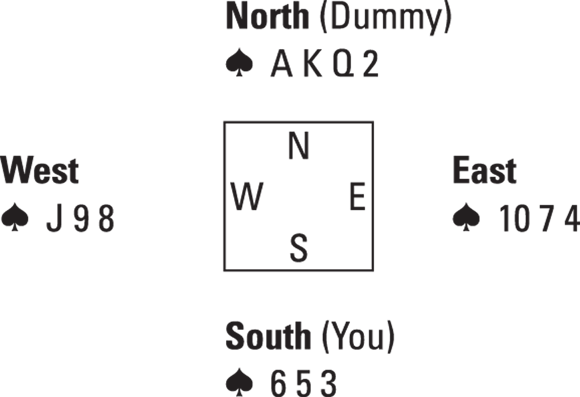

Driving out the ace is a great way of setting up extra tricks. The cards in Figure 3-1 provide an example of a suit you can attack to drive out the ace.

In Figure 3-1, you can’t count a single sure spade trick because your opponent (East) has the ♠A. Yet the four spades in the dummy — ♠KQJ10 — are extremely powerful. (Any suit that contains four honor cards is considered powerful.)

Suppose that the lead is in your hand from the preceding trick, and you lead a low spade (the lowest spade you have — in this case, the ♠3). West, seeing the dummy has very strong spades, plays her lowest card, the ♠2; you play the ♠10 from the dummy; and East decides to win the trick with the ♠A. You may have lost the lead, but you have also driven out the ♠A. The dummy remains with the ♠KQJ, all winning tricks. You have established three sure spade tricks where none existed.

Suits with three or more equal honor cards in one hand are ideal for suit establishment. When you see the KQJ or the QJ10 in either your hand or the dummy, sure tricks in those suits can eventually be developed if you attack them early!

Suits with three or more equal honor cards in one hand are ideal for suit establishment. When you see the KQJ or the QJ10 in either your hand or the dummy, sure tricks in those suits can eventually be developed if you attack them early!

Surrendering the lead twice to the ace and the king

When you’re missing just the ace, you can establish the suit easily by just leading one equal honor after another until an opponent takes the ace. However, if you’re missing both the ace and the king, you will have to give up the lead twice to take later tricks.

Bridge is a game of giving up the lead to get tricks back. Don’t fear giving up the lead. Your high honor cards in the other suits protect you by allowing you to eventually regain the lead and pursue your goal of establishing tricks.

Bridge is a game of giving up the lead to get tricks back. Don’t fear giving up the lead. Your high honor cards in the other suits protect you by allowing you to eventually regain the lead and pursue your goal of establishing tricks.

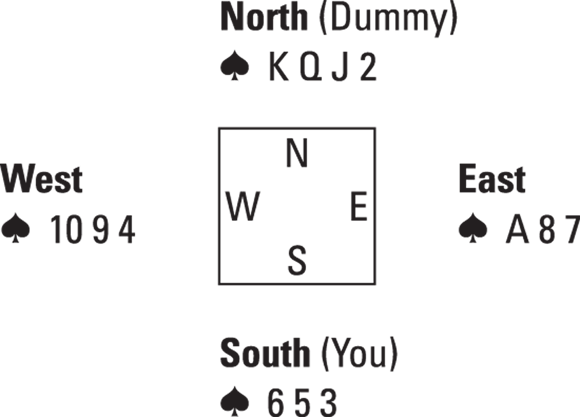

Figure 3-2 shows a suit where you have to swallow your pride twice before you can establish your lower honor cards.

Notice that the dummy in Figure 3-2 has a sequence of cards headed by three equal honors — the ♠QJ10. The ♠9, though not considered an honor card, is equal to the ♠QJ10 and has the same value. When you have a sequence of equals, all the cards have equal power to take tricks — or to drive out opposing honor cards. For example, you can use the ♠9 or the ♠Q to drive out your opponent’s ♠K or ♠A.

In Figure 3-2, your opponents hold the ♠AK. To compensate, you have the ♠QJ109, four equals headed by three honors — a very good sign. You lead a low spade, the ♠2; West plays the ♠5; you play the ♠9 from the dummy; and East takes the trick with the ♠K. You’ve driven out one spade honor. One more to go. Your spades still aren’t established, but you’re halfway home! The next time you have the lead, lead a low spade, the ♠3, and then play the ♠10 from the dummy, driving out the ♠A. Guess what? You started with zero sure spade tricks, but now you have two: the ♠Q and ♠J.

Playing the high honors from the short side first

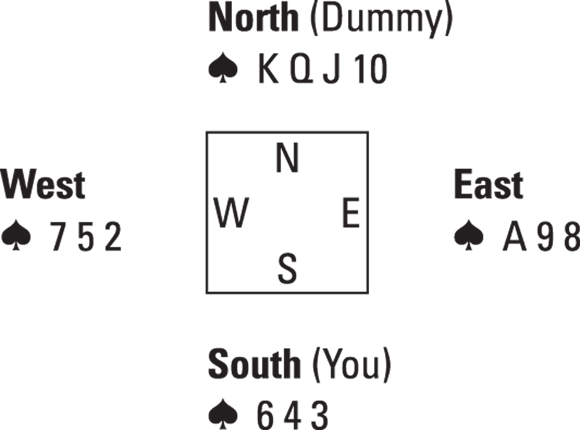

Never forget this simple and ever-so-important rule: When attacking an unequally divided suit, where either your hand or the dummy holds more cards than the other in that suit, play the high equal honors from the shorter side first (see Figure 3-3). Doing so enables you to end up with the lead on the long side (the dummy), where the remainder of the winning spades are. If you remember to play your equal honors from the short side first, your partner will kneel down and declare you Ruler of the Universe.

Never forget this simple and ever-so-important rule: When attacking an unequally divided suit, where either your hand or the dummy holds more cards than the other in that suit, play the high equal honors from the shorter side first (see Figure 3-3). Doing so enables you to end up with the lead on the long side (the dummy), where the remainder of the winning spades are. If you remember to play your equal honors from the short side first, your partner will kneel down and declare you Ruler of the Universe.

Liberation time! As you see in Figure 3-3, the short hand (your hand) has two equal honor cards, the ♠KQ. Start by playing the ♠K, the higher honor on the short side, and a low spade from the dummy, the ♠5. As it happens, East must take the trick with the ♠A because she doesn’t have any other spades.

You’ve established your spades because the ♠A is gone, but you still need to remember the five-star tip of playing the high remaining equal honor from the short side next. When you or dummy next regains the lead in another suit, play the ♠Q, which takes the trick, and then lead the ♠4. The dummy remains with the ♠J109, all winning tricks. You have established four spade tricks by playing the high card from the short side twice.

Using length to your advantage with no high honor in sight

In this section, you hit the jackpot — we show you how to establish tricks in a suit where you have the J1098 but you’re missing the ace, king, and queen!

If you don’t have any of the three top dogs but you have four or more cards in the suit, you can still scrape a trick or two out of the suit. When you have length (usually four or more cards of the same suit), you know that even after your opponents win tricks with the ace, king, and queen, you still hold smaller cards in that suit, which become — voilà! — winners.

Perhaps you’re wondering why you’d ever want to squeeze some juice out of a suit in which you lack the ace, king, and queen. The answer: You may need tricks from an anemic suit like this to make your contract. Sometimes you just get the raw end of the deal, and you need to pick up tricks wherever you can eek them out.

Perhaps you’re wondering why you’d ever want to squeeze some juice out of a suit in which you lack the ace, king, and queen. The answer: You may need tricks from an anemic suit like this to make your contract. Sometimes you just get the raw end of the deal, and you need to pick up tricks wherever you can eek them out.

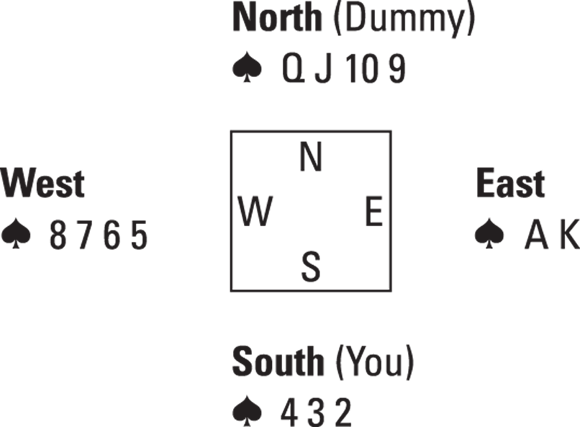

When you look at the dummy and see a suit such as the one in Figure 3-4, try not to shriek in horror.

True, the spades in Figure 3-4 don’t look like the most appetizing suit you’ll ever have to deal with, but don’t judge a book by its cover. You can get some tricks out of this suit because you have the advantage of length: You have a total of eight spades between the two hands. The strength you get from numbers helps you after you drive out the ace, king, and queen.

Suppose you need to develop two tricks from this hopeless-looking, forsaken suit. You start with a low spade, the ♠2, which is taken by West’s ♠Q (the dummy and East each play their lowest spade, the ♠7 and ♠5, respectively). After you regain the lead in some other suit, lead another low spade, the ♠3, which is taken by West’s ♠K (the dummy plays the ♠8, and East plays her last spade, the ♠6). After you gain the lead again in another suit, lead your last spade, the ♠4, which loses to West’s ♠A (the dummy plays the ♠9). You have lost the lead again, but you have accomplished your ultimate goal: The dummy now holds two winning spades — the ♠J10. Nobody at the table holds any more spades; if the dummy can win a trick in another suit, you can go right ahead and cash those two spade tricks. You had to work, but you did it!

Sometimes a friendly opponent (in this case West) will help you out by taking spades tricks early, leaving you with good spades in the dummy without your having to do any work!

Sometimes a friendly opponent (in this case West) will help you out by taking spades tricks early, leaving you with good spades in the dummy without your having to do any work!

Practicing establishment

Practice makes perfect, they say, so we want you to practice making your contract by establishing tricks. In this section, you hold the entire hand shown in Figure 3-5. Your final contract is for 12 tricks. West leads the ♠J. Now you need to do your thing and establish some tricks.

Before you even think of playing a card from the dummy, count your sure tricks (see Book 5, Chapter 2 if you need some help counting sure tricks):

- Spades: You have three sure tricks — ♠AKQ.

- Hearts: You have another three sure tricks — ♥AKQ. (Don’t count the ♥J; you have three hearts in each hand, so you can’t take more than three tricks.)

- Diamonds: No ace = no sure tricks. Sad.

- Clubs: You have three sure tricks — ♣AKQ.

You have nine sure tricks, but you need 12 tricks to make your contract. You must establish three more tricks. Look no further than the dummy’s magnificent diamond suit. If you drive out the ♦A, you can establish three diamond tricks and have 12 just like that. Piece of cake.

When you need to establish extra tricks, pick the suit you plan to work with and start establishing immediately. Do not take your sure tricks in other suits until you establish your extra needed tricks. Then take all your tricks in one giant cascade. Please reread this tip!

When you need to establish extra tricks, pick the suit you plan to work with and start establishing immediately. Do not take your sure tricks in other suits until you establish your extra needed tricks. Then take all your tricks in one giant cascade. Please reread this tip!

First you need to deal with West’s opening lead, the ♠J. You have a choice: You can win the trick in either your hand with the ♠A or in the dummy with the ♠Q. In general, with equal length on both sides, you want to leave a high spade in each hand. Leaving the king in the dummy and the ace in your hand gives you an easier time going back and forth if necessary. However, on this hand it really doesn’t matter where you win the trick; you have three spade tricks regardless. But to keep in practice, say you take it with the queen.

Remember, your objective is to establish tricks in your target suit: diamonds. Following your game plan, you lead the ♦K from the dummy. West takes the trick with the ♦A and then leads the ♠10. Presto — your three remaining diamonds in the dummy, ♦QJ10, have just become three sure tricks because you successfully drove out the ace. Your sure-trick count has just ballooned to 12. Don’t look now, but you have the rest of the tricks and have just made your contract.

Next comes the best part: the mop-up, taking your winning tricks. You capture West’s return of the ♠10 with the ♠K. Then you take your three established diamonds, your three winning hearts, your three winning clubs, and finally your ♠A. You now have 12 tricks, three in each suit. Ah, the thrill of victory.

Steering clear of taking tricks before establishing tricks

Establishing extra needed tricks is all about giving up the lead. Sometimes you need to drive out an ace, a king, or an ace and a king. Giving up the lead to establish tricks can be painful for a beginner, but you must steel yourself to do it.

You may hate to give up the lead for fear that something terrible may happen. Something terrible is going to happen — if you’re afraid to give up the lead to establish a suit. Most of the time, beginners fail to make their contracts because they don’t establish extra tricks soon enough. Very often, beginners fall into the trap of taking their sure tricks before establishing tricks.

You may hate to give up the lead for fear that something terrible may happen. Something terrible is going to happen — if you’re afraid to give up the lead to establish a suit. Most of the time, beginners fail to make their contracts because they don’t establish extra tricks soon enough. Very often, beginners fall into the trap of taking their sure tricks before establishing tricks.

We know you’d never commit such a grievous error as taking sure tricks before you establish other needed tricks. But just for the fun of it, take a look at Figure 3-6 to see what happens when you make this mistake. This isn’t going to be pretty, so clear out the children.

In this hand (showing all the cards from the hand in Figure 3-5), the opening lead is the ♠J, and you need to take 12 tricks. Suppose you take the first three spade tricks with the ♠AKQ, and then the next three heart tricks with the ♥AKQ, and finally the next three club tricks with the ♣AKQ. Figure 3-7 shows what’s left after you take the first nine tricks. (Remember: You need to take 12 tricks.)

You lead a low diamond. But guess what — West takes the trick with the ♦A. The hairs standing up on the back of your neck may tell you what I’m going to say next: West has all the rest of the tricks! West remains with a winning spade, a winning heart, and a winning club. Nobody else at the table has any of those suits, so all the other players are forced to discard. West’s three cards are all winning tricks, and those great diamonds in the dummy are nothing but dead weight, totally worthless.

A word to the wise: Nothing good can happen to you if you take sure tricks before establishing extra needed tricks.

A word to the wise: Nothing good can happen to you if you take sure tricks before establishing extra needed tricks.

Taking Tricks with Small Cards

Grab a man off the street, and he can take tricks with aces and kings. But can that same man take tricks with 2s and 3s? Probably not, but you can!

Only very rarely do you get a hand dripping with all the honor cards you need to make your contract. Therefore, you must know how to take tricks with the smaller cards. Small cards are cards that are lower than honor cards. They are also called low cards or spot cards. You seldom have enough firepower (aces and kings) to make your contract without these little fellows.

Only very rarely do you get a hand dripping with all the honor cards you need to make your contract. Therefore, you must know how to take tricks with the smaller cards. Small cards are cards that are lower than honor cards. They are also called low cards or spot cards. You seldom have enough firepower (aces and kings) to make your contract without these little fellows.

Small cards frequently take tricks when attached to long suits (four or more cards in the suit). Eventually, after all the high honors in a suit have been played, the little guys start making appearances. They may be bit actors when the play begins, but before the final curtain is drawn, they’re out there taking the final bows — and taking tricks.

In the following sections, we give you the scoop on using small cards to your great advantage.

Turning small cards into winning tricks: The joy of length

Deuces (and other small cards for that matter) can take tricks for you when you have seven cards or more in a suit between the two hands. You may then have the length to outlast all your opponents’ cards in the suit. Figure 3-8 shows a hand where this incredible feat of staying power takes place.

You choose to attack spades in the hand in Figure 3-8. Because the ♠AKQ in the dummy are all equals, the suit can be started from either your hand or the dummy. Pretend that the lead is in your hand. You begin by leading a low spade, the ♠3, to the ♠Q in the dummy, and both opponents follow suit. With the lead in the dummy, continue by leading the ♠K and then the ♠A from the dummy. The opponents both started with three spades, meaning that neither opponent has any more spades. That tiny ♠2 in the dummy is a winning trick. It has the power of an ace! The frog has turned into a prince.

Whenever you have four cards in a suit in one hand and three in the other, good things can happen. If your opponents’ six cards are divided three in each hand and you lead the suit three times, leaving each opponent without any cards in that suit, you’re destined to take a trick with any small card attached to the four-card suit.

Whenever you have four cards in a suit in one hand and three in the other, good things can happen. If your opponents’ six cards are divided three in each hand and you lead the suit three times, leaving each opponent without any cards in that suit, you’re destined to take a trick with any small card attached to the four-card suit.

Don’t expect that fourth card to turn into a trick every time, though. Your opponents’ six cards may not be divided 3-3 after all. They may be divided a more likely 4-2, as you see in Figure 3-9.

Don’t expect that fourth card to turn into a trick every time, though. Your opponents’ six cards may not be divided 3-3 after all. They may be divided a more likely 4-2, as you see in Figure 3-9.

When you play the ♠AKQ as you do in Figure 3-9, East turns up with four spades, so your ♠2 won’t be a trick. After you play the ♠AKQ, East remains with the ♠J, a higher spade than your ♠2. Live with it.

Bridge is a game of strategy and luck. When it comes to taking tricks with small cards, you just have to hope that the cards your opponents hold divide evenly (3-3 instead of 4-2, for example).

Bridge is a game of strategy and luck. When it comes to taking tricks with small cards, you just have to hope that the cards your opponents hold divide evenly (3-3 instead of 4-2, for example).

Turning low cards into winners by driving out high honors

Sometimes you have to drive out an opponent’s high honor card (could be an ace, a king, or a queen) before you can turn your frogs into princes (or turn your deuces into tricks). Figure 3-10 shows you how (with a little luck) you can turn a deuce into a winner.

With the cards shown in Figure 3-10, your plan is to develop (or establish) as many spade tricks as possible, keeping a wary eye on turning that ♠2 in the dummy into a winner. Suppose you begin by leading a low spade, the ♠3, and West follows with a low spade, the ♠4. You play the ♠J from the dummy, which loses to East’s ♠A. At this point, you note the following points:

- The ♠KQ in the dummy are now both winning tricks because your opponents’ ♠A is gone.

- Your opponents started with six spades. By counting cards, you know that your opponents now have only four spades left. Four is your new key number.

After regaining the lead by winning a trick in another suit, lead another low spade, the ♠5, to the ♠Q in the dummy (with both opponents following suit). Your opponents now have two spades left between them. When you continue with the ♠K, both opponents follow suit again. They now have zero spades left — triumph! The ♠2 in the dummy is now a sure trick. Deuces love to take tricks — doing so makes them feel wanted.

Make sure you count the cards in the suit you’re attacking. You’re in a pretty sad state if you have to leave a low card in your hand or the dummy untouched because you don’t know (or aren’t sure) whether it’s a winner.

Make sure you count the cards in the suit you’re attacking. You’re in a pretty sad state if you have to leave a low card in your hand or the dummy untouched because you don’t know (or aren’t sure) whether it’s a winner.

Losing a trick early by making a ducking play

Suits that have seven or eight cards between your hand and the dummy, including the ace and the king, lend themselves to taking extra tricks with lower cards, even though you have to lose a trick in the suit. Why do you have to lose a trick in the suit? Because the opponents have the queen, the jack, and the 10 between them. After you play the ace and the king, the opponent with the queen is looking at a winning trick.

When you know you have to lose at least one trick in a suit that includes the ace and king, face the inevitable and lose that trick early by playing low cards from both your hand and the dummy. Taking this dive early on is called ducking a trick. It only hurts for a little while.

When you know you have to lose at least one trick in a suit that includes the ace and king, face the inevitable and lose that trick early by playing low cards from both your hand and the dummy. Taking this dive early on is called ducking a trick. It only hurts for a little while.

Ducking a trick is a necessary evil when playing Bridge. A ducking play in a suit that has an inevitable loser allows you to keep your controlling cards (the ace and the king) so you can use them in a late rush of tricks.

When you duck a trick and then play the ace and king, you wind up in the hand where the small cards are — just where you want to be. In the following sections, we present two situations in which you can duck a trick successfully.

When you have seven cards between the two hands

The cards in Figure 3-11 show how successful ducking a trick can be. You have seven cards between the two hands with ♠AK in the dummy — a perfect setup for ducking a trick. You can only hope that your opponents’ six cards are divided 3-3 so they’ll run out of spades before you do. To find out, you have to play the suit three times.

You know you have to lose at least one spade trick because your opponents hold ♠QJ10 between them. Because you have to lose at least one spade trick, your best bet is to lose the trick right away, keeping control (the high cards) of the suit for later.

Play a low spade from both hands! No, you aren’t giving out presents; actually, you’re making a very clever ducking play by letting your opponents have a trick they’re entitled to anyway.

Play a low spade from both hands! No, you aren’t giving out presents; actually, you’re making a very clever ducking play by letting your opponents have a trick they’re entitled to anyway.

After you concede the trick with the ♠2 from your hand and the ♠4 from the dummy, you can come roaring back with your big guns, the ♠K and the ♠A, when you regain the lead. Notice that because your opponents’ spades are divided 3-3, that little ♠6 in the dummy takes a third trick in the suit — neither opponent has any more spades.

When you have eight cards between the two hands

If the dummy has a five-card suit headed by the ace and the king facing three small cards, you can usually take two extra tricks with a ducking play. See Figure 3-12, where you make a ducking play, and then watch the tricks come rolling in.

In Figure 3-12, the opponents have five spades between the two hands, including the ♠QJ1098. You have to lose a spade trick no matter what, so lose it right away by making one of your patented ducking plays. Lead the ♠2. West plays the ♠9, you play the ♠3 from the dummy, and East plays the ♠8. West wins the trick. Not to worry — you’ll soon show them who’s boss!

The next time either you or the dummy regains the lead, play the ♠K and ♠A, removing all of your opponents’ remaining spades. The lead is in the dummy, and the dummy remains with ♠64, both winning tricks.

When you have five cards in one hand and three in the other, including the ace and the king, you have a chance to take four tricks by playing a low card from both hands at your first opportunity. This ducking play allows you to save the highest cards in the suit, intending to come swooping in later to take the remaining tricks.

When you have five cards in one hand and three in the other, including the ace and the king, you have a chance to take four tricks by playing a low card from both hands at your first opportunity. This ducking play allows you to save the highest cards in the suit, intending to come swooping in later to take the remaining tricks.

Finding heaven with seven small cards

Having any seven cards between the two hands may mean an extra trick for you — if your opponents’ cards are divided 3-3. The hand in Figure 3-13 shows you how any small card(s) can morph into a winner when your opponents’ cards are split evenly. You have seven cards between your hand and the dummy, the signal that something good may happen for your small cards. Of course, you’d be a little happier if you had some higher cards in the suit (such as an honor or two), but beggars can’t be choosers.

Remember Cinderella and how her stepsisters dressed her up to look ugly even though she was beautiful? Well, those five tiny spades in the South hand are like Cinderella — you just have to cast off the rags to see the beauty underneath.

Suppose you lead the ♠2, and West takes the trick with the ♠J. Later, you lead the ♠3, and West takes that trick with the ♠Q. You’ve played spades twice, and because you’ve been counting those spades, you know that your opponents have two spades left.

After you regain the lead, you again lead a rag (low card) — in this case, the ♠5. Crash, bang! West plays the ♠A, and East plays the ♠K. Now they have no more spades, and the two remaining spades in your hand, the ♠7 and ♠6, are winning tricks. You conceded three spade tricks (tricks they had coming anyway) but established two tricks of your own by sheer persistence.

Avoiding the tragedy of blocking a suit

Even when length is on your side, you need to play the high honor cards from the short side first. Doing so ensures that the lead ends up in the hand with the length — and therefore the winning tricks. If you don’t play the high honor(s) from the short side first, you run the risk of blocking a suit. You block a suit when you have winning cards stranded in one hand and no way to enter that hand in order to play those winning cards. It hurts to even talk about it.

Even when length is on your side, you need to play the high honor cards from the short side first. Doing so ensures that the lead ends up in the hand with the length — and therefore the winning tricks. If you don’t play the high honor(s) from the short side first, you run the risk of blocking a suit. You block a suit when you have winning cards stranded in one hand and no way to enter that hand in order to play those winning cards. It hurts to even talk about it.

Figure 3-14 shows you a suit that’s blocked from the very start. It’s a Bridge tragedy: seeing the dummy come down with a strong suit, only to realize that it’s blocked and you can’t use it. You have five spade tricks but may be able to take only two. After you play ♠AK, you’re fresh out of spades, and the dummy remains with the ♠QJ10. Without an entry to the dummy, the ♠QJ10 are stranded never to be used. Yes, it’s very sad.

If you don’t have an entry (a winning card) in another suit to get the lead over to the dummy (called a dummy entry), dummy’s three winning spades will die on the vine. A side-suit ace is a certain dummy entry, and a side-suit king or queen may turn out to be a dummy entry.

The more poignant tragedy is when you accidentally block a suit by failing to play the high card(s) from the short side first. Then you wind up in the wrong hand, instead of winding up in the long hand where the winning tricks are. Instead, you wind up in the short hand that has no more cards in the suit. The long hand may not have a side-suit entry to enter the hand with the winning tricks. It hurts.

The more poignant tragedy is when you accidentally block a suit by failing to play the high card(s) from the short side first. Then you wind up in the wrong hand, instead of winding up in the long hand where the winning tricks are. Instead, you wind up in the short hand that has no more cards in the suit. The long hand may not have a side-suit entry to enter the hand with the winning tricks. It hurts.

When you have equal honors in your hand (where they can’t be seen), such as the KQJ, and want to lead one, use the higher or highest equal to do your dirty work. It is more deceptive. Trust us.

When you have equal honors in your hand (where they can’t be seen), such as the KQJ, and want to lead one, use the higher or highest equal to do your dirty work. It is more deceptive. Trust us.

Suits with three or more equal honor cards in one hand are ideal for suit establishment. When you see the KQJ or the QJ10 in either your hand or the dummy, sure tricks in those suits can eventually be developed if you attack them early!

Suits with three or more equal honor cards in one hand are ideal for suit establishment. When you see the KQJ or the QJ10 in either your hand or the dummy, sure tricks in those suits can eventually be developed if you attack them early! You may hate to give up the lead for fear that something terrible may happen. Something terrible is going to happen — if you’re afraid to give up the lead to establish a suit. Most of the time, beginners fail to make their contracts because they don’t establish extra tricks soon enough. Very often, beginners fall into the trap of taking their sure tricks before establishing tricks.

You may hate to give up the lead for fear that something terrible may happen. Something terrible is going to happen — if you’re afraid to give up the lead to establish a suit. Most of the time, beginners fail to make their contracts because they don’t establish extra tricks soon enough. Very often, beginners fall into the trap of taking their sure tricks before establishing tricks.