Counting Sure Tricks after the Dummy Comes Down

The old phrase “You need to know where you are to know where you’re going” comes to mind when you’re playing Bridge. After you know your final contract (how many tricks you need to take), you then need to figure out how to win all the tricks necessary to make your contract.

Depending on which cards you and your partner hold, your side may hold some definite winners, called sure tricks — tricks you can take at any time right from the get-go. You should be very happy to see sure tricks either in your hand or in the dummy. You can never have too many sure tricks.

Sure tricks depend on whether your team has the ace in a particular suit. Because you get to see the dummy after the opening lead, you can see quite clearly whether any aces are lurking in the dummy. If you notice an ace, the highest ranking card in the suit, why not get greedy and look for a king, the second-highest ranking card in the same suit? Two sure tricks are better than one!

Counting sure tricks boils down to the following points:

Counting sure tricks boils down to the following points:

- If you or the dummy has the ace in a suit (but no king), count one sure trick.

- If you have both the ace and the king in the same suit (between the two hands), count two sure tricks.

- If you have the ace, king, and queen in the same suit (between the two hands), count three sure tricks. Happiness!

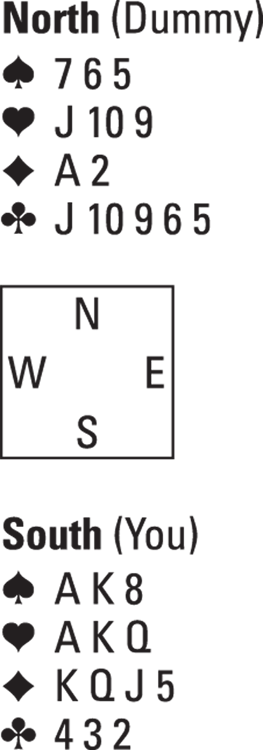

In Figure 2-1, your final contract is for nine tricks. After you settle on the final contract, the play begins. West makes the opening lead and decides to lead the ♠Q. Down comes the dummy, and you swing into action, but first you need to do a little planning. You need to count your sure tricks. What follows in this section is a sample hand and diagrams where we demonstrate how to count sure tricks.

Eyeballing your sure tricks in each suit

You count your sure tricks one suit at a time. After you know how many tricks you have, you can make further plans about how to win additional tricks. We walk you through each suit in the following sections, showing you how to count sure tricks.

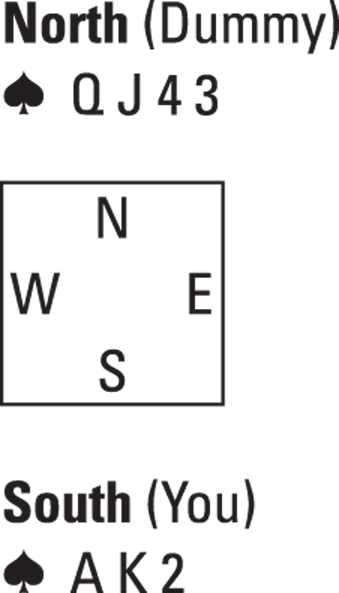

Recognizing the two highest spades

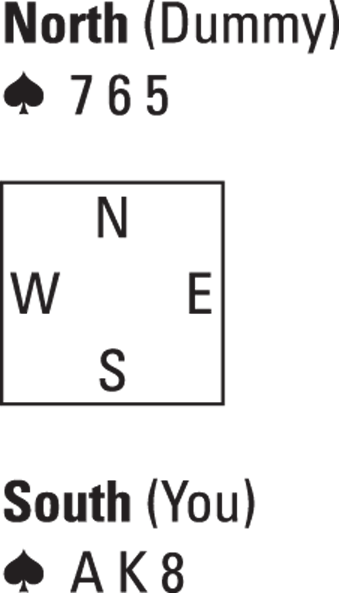

When the dummy comes down, you can see that your partner has three small spades (♠7, ♠6, and ♠5) and you have the ♠A and ♠K, as you see in Figure 2-2.

Because the ♠A and the ♠K are the two highest spades in the suit, you can count two sure spade tricks. (If you or the dummy also held the ♠Q, you could count three sure spade tricks.)

When you have sure tricks in a suit, you don’t have to play them right away. You can take sure tricks at any point during the play of the hand.

When you have sure tricks in a suit, you don’t have to play them right away. You can take sure tricks at any point during the play of the hand.

Counting up equally divided hearts

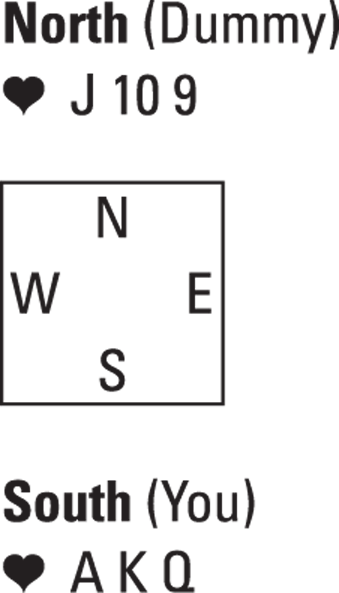

Figure 2-3 shows the hearts that you hold in this hand. Notice that you and the dummy have the six highest hearts in the deck: the ♥AKQJ109 (the highest five of these are known as honor cards).

Your wonderful array of hearts is worth only three sure tricks because both hands have the same number of cards. When you play a heart from one hand, you must play a heart from the other hand. As a result, after you play the ♥AKQ, the dummy won’t have any more hearts left and neither will you. You wind up with only three heart tricks because the suit is equally divided (you have the same number of cards in both hands).

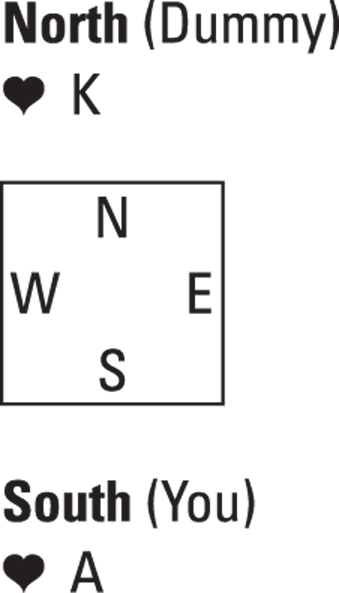

When you have an equal number of cards in a suit on each side, you can never take more tricks than the number of cards in each hand. For example, if you both hold four hearts, it doesn’t matter how many high hearts you have between your hand and the dummy; you can never take more than four heart tricks. Take a look at Figure 2-4 to see how the tragic story of an equally divided suit unfolds.

When you have an equal number of cards in a suit on each side, you can never take more tricks than the number of cards in each hand. For example, if you both hold four hearts, it doesn’t matter how many high hearts you have between your hand and the dummy; you can never take more than four heart tricks. Take a look at Figure 2-4 to see how the tragic story of an equally divided suit unfolds.

In Figure 2-4, you have only one heart in each hand: the ♥A and the ♥K. All you can take is one lousy heart trick. If you lead the ♥A, you have to play the ♥K from the dummy. If the dummy leads the ♥K first, you have to “overtake” it with your ♥A. This is the only time you can have the ace and king of the same suit between your hand and dummy and take only one trick. It’s too sad for words.

Attacking unequally divided diamonds

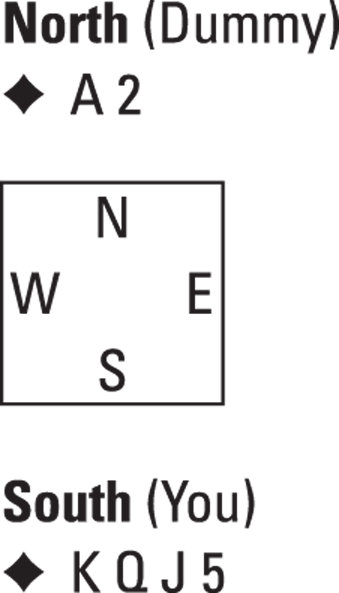

In Figure 2-5, you can see that South holds four diamonds (♦K, ♦Q, ♦J, and ♦5), while North holds only two (♦A and ♦2). When one partner holds more cards in a suit, the suit is unequally divided.

Strong unequally divided suits offer oodles of tricks, provided that you play the suit correctly. For example, take a look at how things play out with the cards in Figure 2-5. Suppose you begin by leading the ♦5 from your hand and play the ♦A from the dummy, which is one trick. Now the lead is in the dummy because the dummy has taken the trick. Continue by playing ♦2 and then play the ♦K from your hand. Now that the lead is back in your hand, play the ♦Q and then the ♦J. Don’t look now, but you’ve just won tricks with each of your honor cards — four in all. Notice if you had played the king first and then the ♦5 over to dummy’s ace, dummy would have no more diamonds and there you’d be with the good queen and jack of diamonds in your hand, perhaps marooned forever!

Lean a little closer to hear a five-star tip: If you want to live a long and happy life with unequally divided suits that contain a number of equal honors (also called touching honors, such as a king and queen or queen and jack), play the high honor cards from the short side first. What does short side mean? In an unequally divided suit, the hand with fewer cards is called the short side. In Figure 2-5, the dummy has two diamonds to your four diamonds, making the dummy hand the short side. When you play the high honor from the short side first, you end up by playing the high honors from the long side, the hand that starts with more cards in the suit, last. (In this example, South has the longer diamonds.) This technique allows you to take the maximum number of tricks possible. And now you know why you started by leading the ♦5 over to the ♦A. You wanted to play the high honor from the short side first. You are getting to be a player!

Lean a little closer to hear a five-star tip: If you want to live a long and happy life with unequally divided suits that contain a number of equal honors (also called touching honors, such as a king and queen or queen and jack), play the high honor cards from the short side first. What does short side mean? In an unequally divided suit, the hand with fewer cards is called the short side. In Figure 2-5, the dummy has two diamonds to your four diamonds, making the dummy hand the short side. When you play the high honor from the short side first, you end up by playing the high honors from the long side, the hand that starts with more cards in the suit, last. (In this example, South has the longer diamonds.) This technique allows you to take the maximum number of tricks possible. And now you know why you started by leading the ♦5 over to the ♦A. You wanted to play the high honor from the short side first. You are getting to be a player!

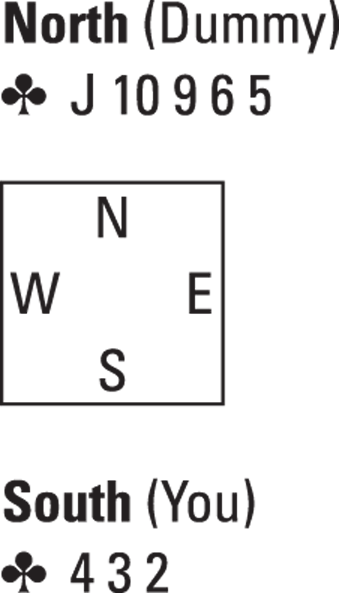

Finding no sure tricks in a suit with no aces: The clubs

When the dummy comes down, you may see that neither you nor the dummy has the ace in a particular suit, such as the club suit in Figure 2-6. You have ♣4, ♣3, and ♣2; the dummy has ♣J, ♣10, ♣9, ♣6, and ♣5.

Not all that pretty, is it? The opponents have the ♣A, ♣K, and ♣Q. You have no sure tricks in clubs because you don’t have the ♣A. If neither your hand nor the dummy has the ace in a particular suit, you can’t count any sure tricks in that suit.

Adding up your sure tricks

After you assess how many sure tricks you have in each suit, you can do some reckoning. You need to add up all your sure tricks and see if you have enough to make your final contract.

Just to get some practice at adding up tricks, go ahead and add up your sure tricks from the hand shown in Figure 2-1. Remember to look at what’s in the dummy’s hand as well as your own cards. The total number of tricks is what’s important, and you have the following:

- Spades: Two sure tricks: ♠A and ♠K.

- Hearts: Three sure tricks: ♥AKQ.

- Diamonds: Four sure tricks: ♦AKQJ.

- Clubs: No sure tricks because you have no ace. Bad break, buddy.

You’re in luck — you have the nine tricks that you need to make your final contract. Now all you have to do is take them. You can do it.

More often than not, you won’t have enough sure tricks to make your contract. You can see what will become of you in Book V, Chapter 3, which deals with various techniques of notrump play designed to teach you how to develop extra tricks when you don’t have all the top cards in a suit.

Before the play of the hand begins, the bidding determines the final contract. However, we have purposely omitted the bidding process in this discussion. For the purpose of this chapter, just pretend the bidding is over and the dummy has come down. We want you to concentrate on how to count and take tricks to your best advantage. After you discover the trick-taking capabilities of honor cards and long suits, the bidding makes much more sense. (We introduce bidding in Book 5,

Before the play of the hand begins, the bidding determines the final contract. However, we have purposely omitted the bidding process in this discussion. For the purpose of this chapter, just pretend the bidding is over and the dummy has come down. We want you to concentrate on how to count and take tricks to your best advantage. After you discover the trick-taking capabilities of honor cards and long suits, the bidding makes much more sense. (We introduce bidding in Book 5,

When you have sure tricks in a suit, you don’t have to play them right away. You can take sure tricks at any point during the play of the hand.

When you have sure tricks in a suit, you don’t have to play them right away. You can take sure tricks at any point during the play of the hand.