Present-day Istanbul, Turkey

Formerly Byzantium

Byzantium, the predecessor of Constantinople, was founded by Greeks, tradition says from Megara, sometime around the middle of the seventh century BC. The site they chose was a small promontory at the southern entrance of the Bosporus, on the left-hand (European) side. This was Thracian territory, and Byzantium is a Thracian name, but there seems to have been little or no friction between the Greek settlers and the Thracians who technically owned the land. If the Byzantines ever paid tribute to a Thracian prince, the sum would soon have become nominal.

The Greek colony prospered from the start, in marked contrast to Chalcedon, the Megaran settlement on the opposite side of the strait. Byzantium had a fine harbour, the famous ‘Golden Horn’, and the currents at the harbour mouth favoured its fishermen; the result was a prosperous tuna fishery – so much so that tuna were depicted prominently on the early coinage of the Byzantine mint. Chalcedon had no such advantages and was often mocked as a ‘city of the blind’ because its settlers had been the first to reach the area and yet managed to pick the inferior site.

By Greek standards Byzantium was a considerable place, strong enough to have a serious stab at maintaining its independence, although not quite strong enough to hold out against the real heavies. Incorporated in the Persian and Athenian empires, it recovered its freedom during the Hellenistic period, when it was slightly to one side of the great powers’ main areas of interest. This interlude ended with the arrival of Roman troops in the region and the imposition of a protectorate that finally made Byzantium one of the subordinate towns of the Roman province of Thrace. (It was not the provincial capital, a role that was taken by PERINTHOS, ninety kilometres (sixty miles) to the west). Throughout this period – and we are talking of 700 years here, the whole period from the fifth century BC to the second century AD – it retained much the same position in the local urban ranking. The trend was undoubtedly up, moving slowly and steadily, except for a brief downturn when the city fathers picked the wrong side in the Roman civil war of AD 193–7. This was eventually won by Septimius Severus, who, annoyed by the way Byzantium had held out against him, had its leading men executed and its walls slighted. His son Caracalla pleaded the town’s case, and eventually Severus relented. In fact he decided to honour it with a new set of walls and, on the south side, a state-of-the-art hippodrome for chariot racing.

Byzantium, even as embellished by Severus, was still a pretty unremarkable place: at the top end of the range for average towns, but without the necessary economic or administrative propellant to get up into the major league. The missing something was supplied by Constantine the Great, who became sole ruler of the Roman Empire in AD 324. By this time the empire had been split into two for administrative purposes – a Latin-speaking west and a Greek-speaking east – and normal practice was for each half to have its own emperor. Constantine didn’t intend to share power with anyone, but he didn’t dispute the reality of the division and, as he wanted to reside in the east, he decided to create what it had hitherto lacked, a capital of equal standing to ROME. He picked Byzantium as the ideal location for the new metropolis. Building began in 324 and colonists were soon flocking in, attracted by Constantine’s offer of free rations for anyone who built a house in his ‘New Rome’. Six years after work started, an official ceremony declared New Rome open for business.

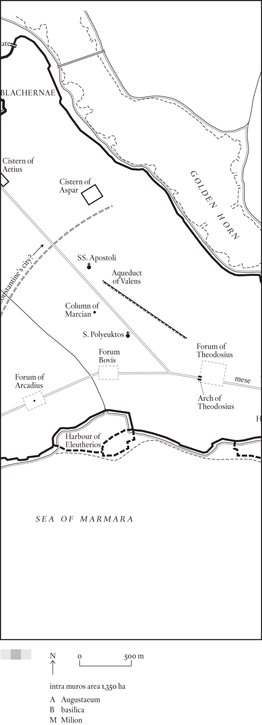

After his death in 335, Constantine’s city was renamed in his honour and the title New Rome disappeared from all but ecclesiastical documents. A century later, when a survey was made of Constantinople’s amenities, it had most of the buildings appropriate for a capital city: an imperial palace; a large number of grand houses for the nobility, the members of the court and the officers of the administration; a cathedral; a senate house; a hippodrome to rival Rome’s Circus Maximus; and some impressive monumental fora. There was, however, still sufficient open space to allow for further growth, and initially it is somewhat puzzling to find the authorities suddenly deciding to build a new set of walls a kilometre or more west of the original boundary of the city. The explanation has nothing to do with any expected increase in population: the idea was to provide extra resources for the city in the case of siege, both in terms of water (several vast cisterns were built in the newly enclosed area) and grazing land for livestock. The additional area was never built over and in the fifteenth century was still being referred to as the chora, meaning countryside.

Constantinople probably reached its classical peak in the sixth century, during the reign of the emperor Justinian, who was responsible for its most famous monument. Early on in his reign, Justinian’s rule had been severely tested when rioting by the Hippodrome factions progressed to looting, general mayhem, and finally a widespread fire that destroyed Constantine’s cathedral of S. Sophia. Justinian rose to the challenge in splendid style. As soon as order had been restored, he directed his architects to draw up plans not for the usual basilican structure but for a vast, centrally planned edifice with a sky-high crowning dome. No expense was to be spared, no delay tolerated. And within five years the emperor was able to enter the new S. Sophia and say, with every justification, ‘Solomon, I have surpassed you.’

S. Sophia was not Justinian’s only project; he rebuilt two other major Constantinian churches, SS. Apostoli (the burial place of the emperors) and S. Irene (alongside S. Sophia), and he constructed some new ones of his own. In the political sphere he launched numerous expeditions intended to recover the lost western provinces, even though he was already at war with Persia and his cabinet was unanimous in advising restraint. In the end he seriously overstrained the resources of the empire, and this at a time when they were probably contracting anyway. The end result was an economic collapse, which put an end to any further growth on Constantinople’s part. At a local level matters weren’t helped by a serious outbreak of bubonic plague in 541.

Worse was to follow in the seventh century. First the Persians, then the Arabs overran Syria and Egypt, and the supply of wheat needed to sustain the capital’s population at its existing level came to an abrupt stop. Numbers must have dropped rapidly over the next generations, and the situation continued to deteriorate in the early eighth century. In 717 an Arab army arrived by sea and laid siege to the city; the garrison managed to hold off these attacks and eventually the Arabs withdrew, but they left behind a city that was just a shadow of its once great self. The aqueduct of Valens, the mainstay of the city’s water supply, lay derelict, no longer needed by such citizens as remained. Against all Roman practice, graves were being dug within the city precincts, indeed within the inner perimeter drawn by Constantine. Both the empire and its metropolis seemed to be in terminal decline.

Against expectation the empire survived, and its capital recovered. A plague attack in 747 hit Constantinople hard but proved to be the last in the series that had begun 200 years earlier. In 756 new settlers brought in from the Greek islands replenished the city’s population, and in 767 the aqueduct of Valens was refurbished for their use. The empire’s frontiers stabilized. Slowly the city took on its old imperial role again. There were to be no new buildings on the scale of H.[agia] Sophia (S. changes to H. as Greek replaces Latin), but at least the resources were once again available to maintain the cathedral’s structure properly and even add the occasional embellishment.

The years either side of AD 1000 marked the peak of this recovery. The Byzantine Empire, as historians term this revived version of the Eastern Roman Empire, never attained the frontiers of its predecessor – the loss of Syria and Egypt to Islam proved permanent – but its possessions in Europe and Anatolia were considerable and seemed secure; the Arabs, it transpired, had shot their bolt. However, in the 1050s a new enemy appeared in the shape of the Turk. Recent converts to Islam, the Turks brought new enthusiasm and, as a migrating people, a new demographic thrust to warfare on the empire’s eastern border. In 1071, at the Battle of Manzikert, they inflicted a catastrophic defeat on the Byzantine army, which opened the way for Turkish tribes to move on to the Anatolian plateau. This movement all but eliminated the Asian half of the empire. Help arrived in the form of the Crusades, but the Crusaders’ aid turned to gall in 1204 with the Fourth Crusade’s seizure and sack of Constantinople. A westerner was placed on the throne of what became, for a brief period (1204–61), the Latin Empire. Eventually the Byzantines recovered their capital along with most of the remaining parts of the empire, but in the interval the Turks had grown ever stronger. In 1354 a contingent of Ottoman Turks crossed the Dardanelles and began conquering the European provinces. The process was near enough complete by 1401 when the Ottoman sultan Bayezid made preliminary moves against Constantinople, now a capital without an empire. The city was saved when Bayezid was overthrown by another eastern potentate, the mighty Timur, but the respite was only temporary. Within fifty years the Ottomans had rebuilt their position, and in 1453, under the eye of the young sultan Mehmet II, the long-overdue assault on the isolated city began. The land walls, never breached in their thousand-year history, crumbled before the Turkish guns, the elite janissary regiments stormed through the gap, followed shortly after by Mehmet himself – now Mehmet Fatih, ‘Mohammed the Conqueror’. H. Sophia became a mosque, and Constantinople one of the capitals of Islam.

Mehmet was determined to restore Constantine’s city to greatness. He cleared away the ruined Church of the Apostles and constructed the colossal Fatih Mosque on the site. He built two palaces, the first overlapping the Forum of Theodosius, the second and more ambitious one on the First Hill where Greek Byzantium had stood. The earlier Eski Saray (‘Old Palace’) has disappeared, but the later complex developed into the Topkapı Palace of today. More importantly, by a mixture of incentive and compulsion, Mehmet raised the city’s population from somewhere around 30,000 on the eve of the siege to perhaps 75,000 at the close of his reign in 1481. This makes it not unlikely that by the end of the century the number of Constantinopolitans had reached 100,000, more than ever before. In fact the great days of the city lay in the future, not the past.

Constantinople, present-day Istanbul, has had four names in all. From its foundation in the mid seventh century BC to the beginning of the fourth century AD it was called Byzantium (strictly Byzantion). With Constantine’s refoundation it became first New Rome (alternatively Second Rome), then, after his death, Constantinople. Some 1,100 years later, in the early fifteenth century, we find the locals beginning to refer to it as Istanbul. This entirely unofficial name is a contraction of the Greek phrase eis ton bolin (‘to the city’) and was used in a manner analogous to the American term ‘downtown’. After the Turkish conquest it became the everyday name, although it did not become the city’s official title until 1927. A version of it, Stamboul, is sometimes used to indicate the Old City, the area within the triangle formed by the land walls, the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara.

The adjectives used to describe the emperor and his empire are even more various. Historians talk of the Eastern Roman emperor and the Eastern Roman Empire, which is fair enough when there were two halves, but is redundant after the fall of the west in AD 476. As far as the (Eastern) Romans were concerned, the surviving part was the Roman Empire tout court. The reason historians like to keep the qualifying adjective is sensible enough – the common language of the east was Greek not Latin – and became stronger with the passage of time. The culmination of this process was the substitution of Greek for Latin in official documents, an event that coincides with the reign of the emperor Heraclius (610–41). Historians mark the changeover by introducing the term ‘Byzantine’ and applying it to both emperor and empire from the seventh century on. Byzantine is certainly a useful term, but it was never used in this sense by the Byzantines themselves; they continued to call themselves and their empire Roman. (A Byzantine for them was an inhabitant of Constantinople.) Of course, they also recognized the term ‘Greek’, and in the medieval period westerners were as likely to call them Greeks as Romans. The much reduced empire of this period was usually referred to as Romania.

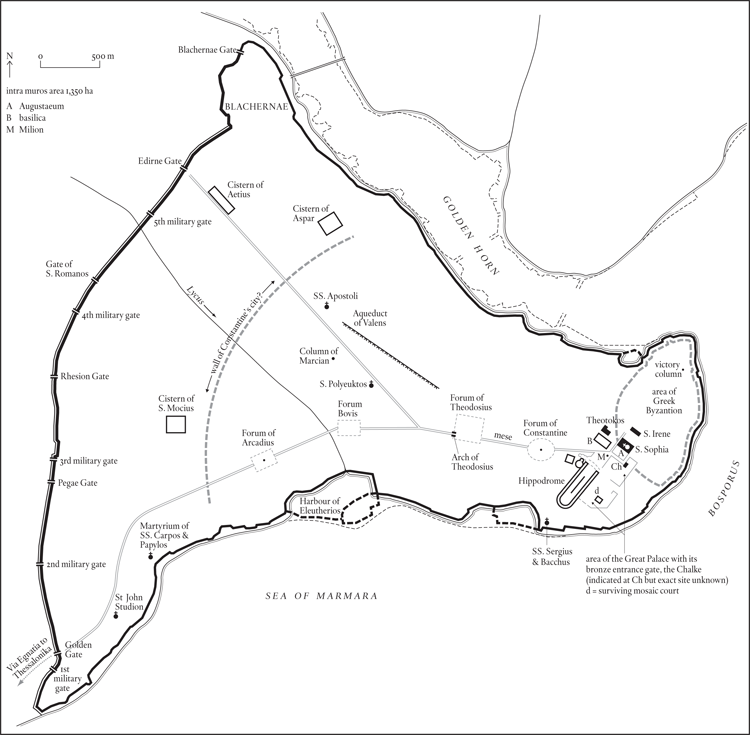

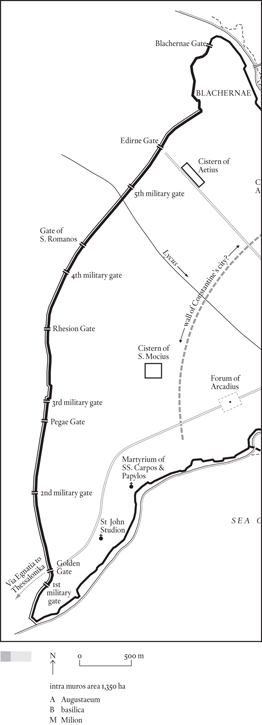

The walls as they exist today are known as the Theodosian Walls, because, with the exception of the Blachernae sector and some stretches of the sea walls, the entire circuit was built during the reign of the emperor Theodosius II (408–50). Blachernae was the site of the only bridge across the Golden Horn, and had doubtless come into existence because of that fact. In Constantine’s day, when the city wall of New Rome stopped well short of Blachernae, it was a discrete township with its own walls. When in 413 Theodosius decided to build a new set of walls for Constantinople, he made Blachernae the starting point for a land wall that ran south to a point on the Sea of Marmara nearly six kilometres (3.6 miles) distant. The salient at the northern end of the land wall corresponds to the western half of Blachernae’s town wall; the rest of the wall follows a near straight line across the peninsula. In 439, with the land wall and its many towers completed, work began on a set of sea walls to protect the shoreline of the city on both its northern face, along the Golden Horn, and its southern aspect, fronting the Sea of Marmara. Shortly after, in 447, an earthquake severely damaged the land wall; it was rebuilt, this time in the form of a double line of walls, in the space of two months. The fact that Attila the Hun was sacking cities throughout the Balkans that year was undoubtedly responsible for the urgency, but the speed of construction didn’t diminish the effectiveness of the work. Constantinople’s land walls were to remain unbreached for the next 1,000 years.

During this period the line of the sea walls was modified, as silting extended the shoreline, most notably at the mouth of the Lycus on the Marmara shore. This raised the intramural area from the 1,350 hectares of late antiquity to a final figure, on the eve of the Turkish conquest, of some 1,385 hectares. The Blachernae wall was also rebuilt on several occasions, so that from being initially the weakest sector, it became the strongest. Otherwise the walls remained essentially the same. The plan doesn’t show the numerous gates in the sea walls that could be supplemented, or bricked up, as occasion demanded. It does, however, show the major gates in the land walls, which were permanent structures. Two sorts need to be distinguished: the city gates, which led to the outside world; and the military gates, which only gave access to the space between the walls. There were six city gates and five military gates. In 1453 the city fell when the Turks bombarded, destroyed and then carried the section of the outer wall opposite the fifth military gate.

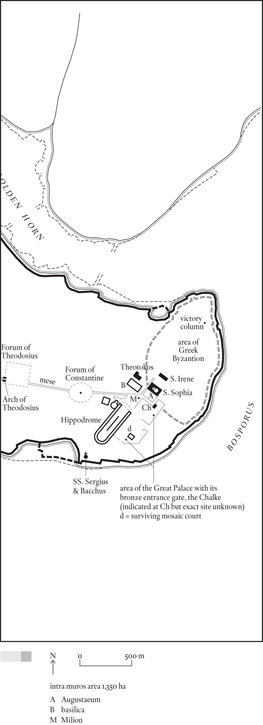

The Theodosian Walls were preceded by two smaller circuits of which nothing remains: the wall of late Greek/early Roman Byzantium, and the wall of Constantinople as originally laid out by Constantine the Great. The wall of Byzantium will have followed the contours of the hill that formed the tip of the peninsula – the First Hill of Constantinople’s seven (see p. 111) – and though there is no archaeological support for it, the perimeter shown on the plan probably isn’t too far from the truth. In that case it will have enclosed an area of seventy to seventy-five hectares. The line suggested for Constantine’s wall is far more problematical. It represents the modern consensus, but an equally good case could be made for a less ambitious circuit crossing the peninsula one to one and a half kilometres further east. This would put the Church of the Apostles, the emperors’ mausoleum, outside the city, something that accords better with Roman practice, for although emperors could, if they chose to, ignore the prohibition on burial within the walls, it was considered good manners not to, as with Hadrian’s mausoleum in Rome.

The original Greek settlement occupied the part of the First Hill where the Topkapı Palace now stands. As time passed – very slowly, we’re talking centuries here – the town spread south until it finally came to cover the entire hill. We read of temples to Athena, Apollo and Poseidon, and of two theatres, large and small, but no trace of any of these buildings has ever been found. Of Byzantium’s walls, all that is recorded is the name of one gate (the Thracian Gate), which opened out on to a flat area (the Thracian Field), which can only be the ground on the top of the ridge between First and Second Hills. In fact nothing remains of the Greek city at all. All we can say is that, given the history of slow growth over a long period of time and the sloping edges of the site, its plan was probably pretty much of a jumble; certainly the fifth-century Description refers to ‘streets and alleys’ in this part of the city (First and Second regions) where in the other regions the same item is simply headed ‘streets’.

The first significant Roman addition to Byzantium’s amenities was the hippodrome donated by Septimius Severus at the beginning of the third century AD. This lay outside the walls of the Greek city, which the emperor had first slighted (following the long siege of the city in 193–6), then restored, maybe even enlarged. But whatever Severus’ benefactions were, they were completely overshadowed a century later, when Constantine chose Byzantium as the site of his New Rome. The area immediately north of the hippodrome – presumably part of the old Thracian Field – was laid out as a monumental plaza, the Augustaeum, with, at or near its centre, the Milion, the Golden Milestone from which all distances in the Eastern Empire were measured. A palace for the emperor was built parallel with the eastern side of the hippodrome. And the hippodrome itself was enormously enlarged, which, as the ground fell away sharply at this point, meant that massive substructures had to be built to support its far end. Constantine also monumentalized the first section of the main road that ran west from the Milion, lining it with porticos, and providing it with a focal point in the shape of a circular or oval forum with a colossal porphyry column at its centre. Needless to say, the column was topped off with a figure of Constantine and the forum was named for him too.

Although Constantine was determined to make his New Rome a match for ‘old’ Rome, he was also keen to emphasize the key difference between the two: his capital was to be a Christian city from the start. So he built a senate house on the north side of his forum, and a basilica just north of the Augustaeum, but no equivalents of the great temples of pagan Rome. Instead there was a vast cathedral, S. Sophia, not finished until 360, in the reign of his son Constantius, and an equally large church on the edge of town, SS. Apostoli, intended to serve as a mausoleum for the emperor and his dynasty.

The last of the Constantinian emperors was Julian the Apostate, who died while campaigning against the Persians in 363. A successor, Valens, had time to build one of the major monuments of Constantinople, an aqueduct spanning the valley between the Fourth and Third Hills, before he too lost his life – and, more importantly, his army – battling against the Goths in 378. The empire made a reasonable recovery from this disaster and the soldier-emperor Theodosius the Great (379–95) was able to pass it on to his sons Honorius (who got the West), and Arcadius (who got Constantinople and the East). Arcadius was succeeded by Theodosius II (408–50). Between them the Theodosians brought the plan of the city to its final form, for although subsequent emperors added new buildings and rebuilt old ones, they didn’t change the city’s essential plan. The main road running west from the Milion has already been mentioned; some way beyond the forum of Constantine it divided into two, a northern branch running along the crest of the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Hills, and a southern branch running parallel to the Marmara coast and crossing the Seventh Hill. The elder Theodosius’ contribution to the city plan was a very grand Forum at the site of the bifurcation. It was a conscious imitation of Trajan’s forum in Rome, and had a similar column with narrative reliefs as its centrepiece, plus a triumphal arch of idiosyncratic design at its western entrance. He also built another, more orthodox arch on the southern road, at a point where it left the city limits and became the Via Egnatia, the military highway that ran across the Balkans to the Adriatic. This arch was later incorporated into the Theodosian Walls, of which it became the Golden Gate. Theodosius’ son Arcadius built a forum too, on the southern branch of the main road; like his father’s it had a column with spiral reliefs, although, unlike his father, Arcadius had no real victories to celebrate. add the wall of Theodosius II, and the enterprise on which Constantine had embarked 124 years earlier was effectively complete.

Constantine wanted his New Rome to have everything ‘old’ Rome had, and that included seven hills and fourteen regions. Regions – administrative districts – were simple enough to organize, but natural features are a bit more difficult to conjure up and Constantinople’s seven hills don’t exactly leap to the eye. What the city certainly has is a central ridge, running from Seraglio Point at the Bosporus end, to the Edirne Gate. Six of the nominated hills are simply high points on this ridge, with the First overlooking the Bosporus and the Sixth just inside the Edirne Gate, the highest point in the city. The Seventh Hill occupies the south-west quarter of the city, separated from the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Hills by the valley of the Lycus. The hills along the crest of the ridge are defined not so much by the saddles between them, which are often barely perceptible, as by the valleys running up to the ridge, particularly on the north side.

The main interest of the regions is that they show the way the population of the city was distributed. To judge by the number of streets in each region, more than 80 per cent of Constantinopolitans lived on the First, Second and Third Hills, i.e. in the eastern third of the intramural area. Looking at the same data in a north versus south sense (as opposed to west versus east), a similar percentage lived in the regions that bordered the Golden Horn, compared to 20 per cent in the regions fronting the Sea of Marmara. The Description of Constantinople from which these statistics are derived dates from the reign of Theodosius II (408–50), but so far as we can tell the pattern was pretty much the same when the city fell to the Ottomans 1,000 years later.

The Description of Constantinople gives the names of the important buildings, the number of streets, of substantial houses, and of officials for each of the fourteen regions of the city. Two of the regions were on the edge of the Constantinian city, eleven on the Fourth Hill and twelve on the Seventh. Two more were certainly beyond it: the settlement of Sycae on the northern side of the Golden Horn (Region 13) and, on the south side but much further west, the enclave of Blachernae (Region 14). Blachernae, which had its own walls, was the site of the only bridge across the Horn, and had doubtless come into existence because of that fact. The remaining ten regions were situated on the first three of the city’s hills, with extensions to the west along the Marmara and Golden Horn shores. Judging from the number of its streets, this area contained nearly 90 per cent of the city’s population; on the other hand it contained only just over 60 per cent of the houses of the better off, who clearly preferred the less crowded suburbs.

The Description is more than somewhat maddening, as it doesn’t use the same categories as the Roman Notitia Dignitatum, ignoring the basic housing units (insulae) and only giving figues for the superior sort (domus). Even they must be defined differently because there are far too many of them by comparison with Rome (4,388, compared to 1,790). In fact, it is very difficult to wring any population data out of the Description, although as previously noted the number of streets in each region does give a picture of the population’s distribution. Perhaps there is an order of magnitude to be obtained from the probability that Regions 1 and 2, the old Greek city of Byzantium, contained about 10,000 people and that therefore the other twelve regions between them may have contained 60,000 people, making 70,000 in all.

How much remains of the early Christian city? Very little from Constantine’s day. The outlines of the Augustaeum and of his forum have been lost in the many rebuildings the city has undergone; no trace remains of his city wall. His Great Palace on the First Hill was abandoned by the later Byzantine emperors, who preferred Blachernae; it was in ruins long before the Turkish conquest, and there is nothing to be seen there today except for a few mosaic floors. All three of his major churches, S. Sophia, S. Irene and SS. Apostoli, were replaced by new versions in Justinian’s reign. His column is still standing, but as a forlorn stump. In fact the most impressive relic of Constantine’s building programme is the eroded brickwork cliff that holds up the southern end of the hippodrome.

The Theodosian works have survived considerably better. Theodosius the Great’s Golden Gate is still there, embedded in his grandson’s wall. Fragments of his other triumphal arch are scattered by the side of the road that runs across the site of his forum, and there are a couple of reliefs from his column built into a neighbouring Turkish bath. The base of Arcadius’ column remains in situ. And the walls of Theodosius II still gird the city, the one feature of the New Rome that is a genuine match for the ‘old’.

When he started work on his new capital, Constantine the Great had at his disposal a supply of wheat sufficient for 80,000 people, this being the amount that Egypt had previously shipped to Rome and was now, because of the decline in Rome’s population, available for alternative use. Constantine diverted the Egyptian grain fleet to his New Rome, where he offered free rations – in perpetuity – to anyone who was prepared to set up house there. As a result the population of Constantinople had reached 40,000 within a few years of his death. His son Constantius seems to have decided that this was enough, and cut the number of rations accordingly. Theodosius I raised the total by a trifling amount (perhaps 400 rations), but we have no record of the figure of 80,000 being restored in full, although it is quoted by several later authors as if it had been. So for the heyday of Roman Constantinople – the fifth century and the first half of the sixth – we have alternative population figures of 40,000 and 80,000. The lower figure is surely preferable, for if Egypt was still shipping out 80,000 rations – a dubious proposition given that the country was probably experiencing the same contraction of resources suffered by other provinces during this period – then the two praesental armies (the forces stationed in the immediate vicinity of the capital, probably numbering about 15,000 each) will have had first call on whatever was available.

Certainly, later emperors had no interest in boosting the city’s population, Justinian going so far as to employ a special officer to ensure that provincials returned home as soon as they had completed their business in the metropolis. By this time the contraction of resources already alluded to was really beginning to bite. A fall in numbers began, initiated by the plague of 542, but continued after its passing. Early in the next century the loss of Egypt, first to the Persians, then to the Arabs, meant that there were, after 618, no more free rations. Population figures will have slumped accordingly, to somewhere in the region of 15,000 to 20,000. This was just enough to mount a successful defence against the small armies fielded by the Avars and Persians in the early seventh century and the maritime expeditions launched by the Arabs in the seventh and early eighth centuries.

From the mid eighth century on, things began to get a bit better, and we can accept a slow recovery to 30,000 by the year 1000. As 30,000 or thereabouts is the figure for the city’s population when it fell to the Turks in 1453, the corollary is that the trend towards larger urban populations characteristic of the later medieval period (the eleventh to fifteenth centuries) compensated for Constantinople’s rapidly diminishing political clout.

In 1477, a quarter-century after the Ottoman conquest, Mehmet II ordered a house count to find out whether his drive to increase the population of his new capital was succeeding or not. He was reassured to find that it had more than doubled, to a total of 65,000. If it continued to grow at the same rate – and we have no reliable figures for the sixteenth century – it would have been well over the 100,000 mark in 1500. Across the Golden Horn on its northern shore, the district of Galata was growing much faster than Stamboul during this period, and it continued to do so subsequently. The first proper census, taken in 1927, showed 691,000 in the city as a whole, but only 200,000 in Stamboul. This figure, incidentally, makes it exceedingly unlikely that late classical or medieval Constantinople ever held anything like this number, for by the 1920s Stamboul was almost entirely built over, something it had never been in its earlier incarnations.