Veneto, Italy

City in the tenth region of Italy, subsequently the late Roman province of Venetia et Histria

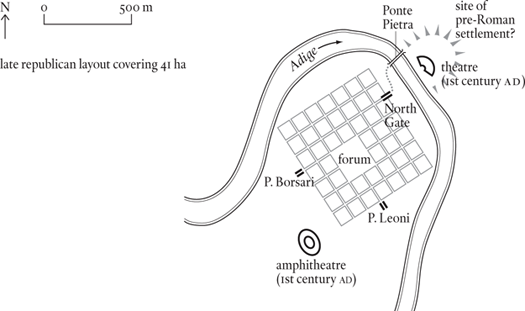

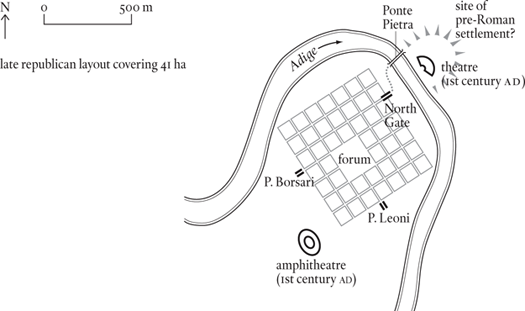

Little is known about early Verona, except that the Romans found a native settlement on the site when they moved into the area north of the Po. There is argument about which natives are meant – the Raeti to the north, the Gauls (specifically the Cenomani of Brescia) to the west, the Veneti to the east, or maybe the Euganei, a local Italic tribe. There is also no certainty as to the first settlement’s exact position, although the consensus favours the San Pietro hilltop on the left bank of the Adige, opposite the loop of the river that encloses the heart of Roman (and modern) Verona. The move from the hilltop to the flat area within the loop is thought to have taken place in the late republican period, i.e. sometime in the first century BC. This marks the starting point of Verona’s history as a classical town.

Roman Verona was laid out in square blocks of which thirty-two survive in the street plan as it exists today. The implication is that the original city was a square with seven blocks on each side, covering an area of forty-one hectares. This reconstruction puts several blocks in the current bed of the Adige, but, as regards the eastern corner this isn’t a problem: we know that the Adige, until relatively recently, made a wider swing around the city on this side, the old bed being marked by the ‘Internato dell’Aqua Morte’ of the present-day street plan. We have no such evidence for the west side, but the shift required is small and seems easier to believe in than an incomplete Roman rectangle. There were at least three gates: preliminary versions of the present-day Porta Borsari and Porta Leoni, and a gate on the north indicated by a track – fossilized in the current street plan – leading from the foot of the Ponte Pietra.

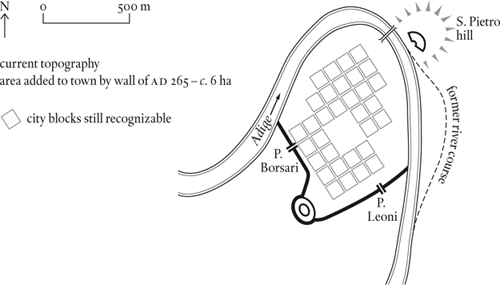

Verona occupies a position of considerable strategic importance and was the site of many battles – between the armies of Vespasian and Vitellius (69), of Philip and Trajan Decius (249), of Constantine and Maxentius (312) and of Stilicho and Alaric (403). In the imperial crisis of the mid third century AD, it became the command and control centre for the emperor Gallienus’ defence of north Italy. A lasting memento of this phase in the town’s history is the inscription of AD 265 on the Porta Borsari celebrating the completion of Gallienus’ new wall for the city. As the plan on p. 389 shows, this wall took in the amphitheatre, giving a new intramural figure of forty-seven hectares.

Procopius’ account of the Gothic War – the reconquest of Italy by the armies of the East Roman emperor Justinian in the mid sixth century – includes an interesting episode involving Verona in 542. A traitor let the Romans into the town by night, and the Gothic garrison was forced to beat a rapid retreat to the San Pietro hill across the river. From this vantage point the Goths could see into the town, where it soon became apparent that it contained only a few Roman soldiers. They could also see that no guard had been posted at the nearest gate. Coming down from the hill they soon swept the Roman force out of the town, which they were to hold on to for the next twenty years. In the end the Romans won, but they had little time to enjoy their victory, Verona falling to the Lombards in 569, the first year of their invasion of Italy. King Alboin made it his capital, and although his successors preferred PAVIA, Verona became the seat of one of the most important Lombard dukes.

Verona obviously had a better Dark Ages than most Italian towns, and may not have lost any population at all. The eleventh century saw the town sharing in the rapid expansion that was a feature of the time, and numbers soon began to build. By 1300, population was approaching 30,000 within a new wall (built 1287–1325) enclosing 365 hectares. At the same density of eighty per hectare, Roman Verona would have had a population of about 5,000, but at its best it may well have done better than this: a peak figure in the area of 6,000 to 7,000 would be fully acceptable.