“Jhesus-Maria, King of England, and you, Duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of the Kingdom of France, you, Guillaume de la Poule, count of Suffort*, Jean, sire of Talbot, and you, Thomas, sire of Scales, who call yourselves lieutenants of the Duke of Bedford, acknowledge the summons of the King of Heaven. Render to the Maid here sent by God the King of Heaven, the keys of all the good towns which you have taken and violated in France. She is here come by God’s will to reclaim the blood royal†. She is very ready to make peace, if you will acknowledge her to be right, provided that France you render, and pay for having held it. And you, archers, companions of war, men-at-arms and others who are before the town of Orleans, go away into your country, by God. And if so be not done, expect news of the Maid who will come to see you shortly, to your very great injury. King of England, if (you) do not so, I am chief-of-war and in whatever place I attain your people in France, I will make them quit it willy nilly‡. And if they will not obey, I will have them all slain; I am here sent by God, the King of Heaven, body for body, to drive you out of all France. And if they will obey I will be merciful to them. And be not of another opinion, for you will not hold the Kingdom of France from God, the King of Heaven, Son of St. Mary, but will hold it for King Charles, the rightful heir, for God, the King of Heaven so wills it, and that is revealed to him by the Maid who will enter into Paris with a goodly company. If you Will not believe the news (conveyed) by God and the Maid, in what place soever we find you, we shall strike into it and there make such great babay, that none so great has been in France for a thousand years, if you yield not to right. And believe firmly that the King of Heaven will send greater strength (more forces) to the Maid than you will be able to bring up against her and her good men-at-arms; and when it comes to blows will it be seen who has the better right of the God of Heaven. You, Duke of Bedford, the Maid prays and requires of you that you cause no more destruction to be done. If you grant her right, still may you come into her company there where the French shall do the greatest feat of arms which ever was done for Christianity. And make answer if you wish to make peace in the city of Orleans. And if you make it not, you shall shortly remember it, to your very great injury. Written this Tuesday of Holy Week (March 22, 1429).” (C.221–222)

THE SIEGE OF ORLEANS

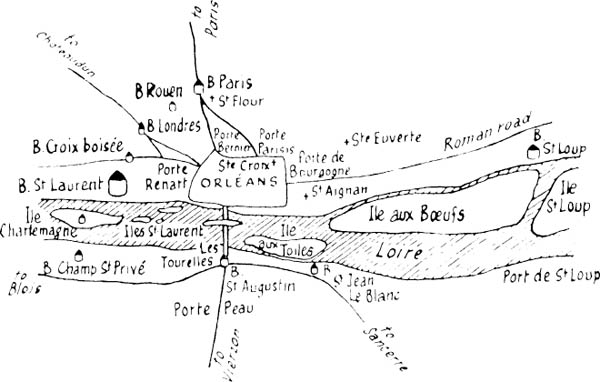

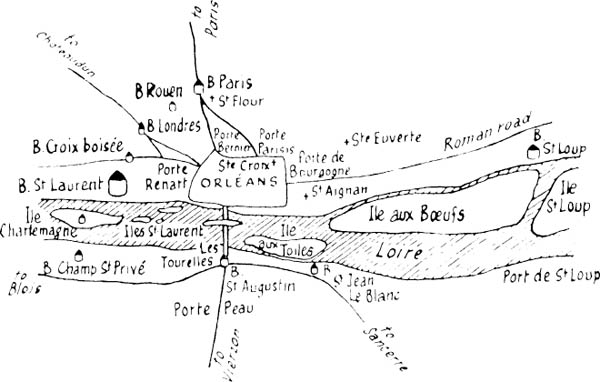

The Captial B preceding certain names means Blockhouse.

It was in these terms that the letter of summons sent by Joan to the English was written, the moment she was made free to act, after the Poitiers examination. And it seems likely that it was from this letter that the enemy first heard of her existence. Until then nothing but vague rumours had gone the rounds, rumours which must have been eagerly seized upon wherever the people were for the French king, but which the English, sure of themselves, had probably made fun of as a lot of old wives’ tales. Up until the moment when Orleans had been delivered, as we shall see in the following quotations, Joan was treated by them as nothing but an adventuress on whom insults should be heaped; thereafter, in the stupefaction caused by her unexpected victory, she was, for them, nothing but a witch and magician.

Orleans was the essential feat of arms, the very sign of her mission, as she herself had expressly stated (see Seguin Seguin’s evidence in the previous chapter). It is therefore necessary to go back a little in time again, in order to follow events in Orleans before Joan arrived.

“The Count de Salebris (John, Earl of Salisbury), who was a very great lord and the most renowned for feats of arms of all the English and who, for Henry, King of England, whose kinsman he was and as his lieutenant and chief of his army in his kingdom, had been present in several battles and diverse encounters and conquests against the French, in which he had always borne himself valliantly, thinking to take by force the city of Orleans which was held by the party of the King its sovereign and lord, Charles, Seventh of that name, had besieged it Tuesday the twelfth day of October 1428 with great power and army which he encamped on the Sologne side and near to one of the villages which is called the Portereau. In this army were with him Messire Guillaume de la Poule, count of Suffort and Messire Jean de la Poule (John de la Pole), his brother, the Lord of Scales—Classidas, of great renown (William Glasdale)—and several other lords and soldiers* both English and others false Frenchmen on their side. But the soldiers who were there (i.e., in Orleans) by way of garrison, had that same day, before the coming of the English, with the aid and council of the citizens of Orleans, pulled down the church and monastery of the Augustins of Orleans and all the houses which were at the Portereau, in order that their enemies could not use them as billets nor there construct fortification against the City.”

The Journal of the Siege of Orleans, from which these details are taken,† was composed, at least as to the part which concerns us (touching the beleaguering and deliverance of the City) from notes written down day by day, some of which can be checked by still extant documents in the town’s archives. It gives the detail of what took place beginning on Tuesday, October 12, 1428.

“The Sunday following (October 17th) hurled the English into the City six score and four stones from bombards and great canon, of which there was one such stone weighed 116 pounds. Among the others, they had installed near Saint-Jean-le-Blanc . . . a great canon which they called Passe-volant. This one hurled stones weighing 80 pounds which did great damage to the houses and buildings of Orleans albeit it killed not nor wounded any unless one woman, named Belle, living near to the Chesnau postern.*

“This same week did the English canon damage or destroy twelve mills which were on the river Loire between the city and the Tourneuve. Accordingly those of the town had made eleven horse-mills which much consoled them. And meanwhile the canons and engines of the English made, against the French within Orleans, several sorties and raids between the Tourelles† of the bridge and Saint-Jean-le-Blanc since that Sunday until Thursday one -and-twentieth day of the same month.‡

“On this day of Thursday, the English assailed a boulevard (rampart) which was made of faggots and earth, before the Tourelles, against which the assault lasted four hours without ceasing, for they began at ten o’clock in the forenoon and did not leave off until two o’clock in the afternoon. There were done several great feats of arms on one side as on the other. The women of Orleans were of great succour, for they ceased not to carry very diligently to them that defended the boulevard, several things necessary, as water, boiling oil and fat, lime, ashes and caltrops. At the end of the assault there were some wounded on both sides but especially the English of whom died more than twelve score. It came to pass that during the assault (there) rode about Orleans the lord de Gaucourt of which he was governor, but in passing before Saint-Pierre-au-Pont, he fell from his horse peradventure, so that he broke his arm. He was at once taken to the baths to have it dressed.

“The Friday following, twenty-second of the month of October, tolled the belfry bell, for the French thought that the English were attacking the Tourelles boulevard from the end of the bridge by way of the mine which they had dug; but they brought themselves not to it in that hour . . . The Saturday following, twenty-third day of this month, those of Orleans burnt and threw down the Tourelles boulevard and abandoned it because it was all mined and was no longer tenable from what the soldiers said.

“The Sunday following twenty-fourth day of October the English attacked and took the Tourelles from the end of the bridge because they were all demolished and broken by the canon and heavy artillery which they had hurled against (them). Thus there was no defence because none dared any longer stay in them.” (J.S.O.07–100)

The information contained in this shows how the English, with great strategic shrewdness, had from the beginning of the siege cut Orleans itself off by severing its only communicating link with what we should now call the “free zone”. This bridge, defended by the Tourelles fortification, and taken on October 24th, was in fact the bridge over the Loire which linked Orleans with the left bank—the part of France which, as we have seen, was still in the French King’s hands. The two fortifications named above, Saint-Jean-le-Blanc and the Augustins were, likewise, on the left bank of the Loire, on the river bank, and they were immediately occupied. Having made themselves masters of this vitally important point, the English settled down to besiege at their leisure a town which was now sure to fall into their hands sooner or later. For the preceding months had witnessed a brilliant advance along the whole front; and in August the Earl of Salisbury had made sure of all the country between Dreux and Chartres, then the towns and countryside of Toury, Le Puiset, Jauville, Meung and Beaugency.

However, this same day of October 24th ended with a serious loss for the whole English Army:

“This day, Sunday, in the evening, the Earl of Salisbury, having with him the Captain Glasdale and several others, went into the Tourelles after they had been taken, the better to look over the site (assiette) of Orleans. But while he was there, looking at the town through the windows of the Tourelles, he was struck by a canon that was said to have been fired from a tower called the Tour Notre-Dame (situated at the west of the town). . . . The canon-shot struck him so in the face that it beat in one half of the cheek and put out one of his eyes. Which was a very great good to this kingdom, for he was chief of the army, the most feared and renowned in arms of all the English.

“The Monday following there arrived in Orleans, to comfort, succour and aid the city, several noble lords, knights, captains and esquires very renowned in warfare in which they were the principals. Jean, Bastard of Orleans, the lord of Saint-Sévère, marshal of France, the lord Du Bueil, messire Jacques de Chabannes, seneschal of the Bourbonnais, and a valiant Gascon captain called Etienne of Vignolles, called La Hire, who was of most great renown, and the valiant men of war who were in his company.

“The Wednesday following, twenty-seventh day of October, departed this life during the night the Earl of Salisbury, in the town of Meung-sur-Loire, where he had been carried from the siege after he had received the canon-shot of which he died. At his death were right dumbfounded and doleful the English maintaining the siege and they made great mourning albeit they did so as secretly as they might for fear lest those of Orleans should perceive it. . . . The earl’s death did great injury to the English and, on the other hand, great profit to the French. Some have said since that the Earl of Salisbury came to that end by the divine judgment of God and they believe it as much because he failed of his promise to the Duke of Orleans, prisoner in England, to whom he had promised to injure none of his lands, as because he spared neither monasteries nor churches but looted them and had them looted as soon as he could enter. . . . Especially there was looted by him the church of Notre-Dame de Clery and its village (bourg).” (J.S.O.100–102)

However, this loss was to be rapidly made good:

“The first day of December following, arrived at the Tourelles of the bridge several English lords of whom among the rest him of greatest renown was messire Jean Talbot, premier baron of England, and the lord of Scales, accompanied by three hundred combatants who brought victuals, canons, bombards and other gear of war by which they have since been hurling against the walls and into Orleans continually and more powerfully than before they had done in the lifetime of the Earl of Salisbury, for they cast such stones as weighed eight score four pounds which wrought much evil and injury against the city and many houses and fine buildings.” (J.S.O.103)

The siege continued during several months without any notable event; at the time the English counted mainly on famine and exhaustion to reduce the town. However, the diarist of the Journal of the Siege did preserve for us some notes worth recording here, for they help us to recapture the atmosphere of the time and place.

There were, for example, the exploits of master Jean, the “culverineer”, a native of Lorraine . . .

“. . . Who was said to be the best master there was in that trade. And well he showed it, for he had a great culverin from which he often hurled . . . so much so that he wounded and killed many English. And to mock them he let himself sometimes fall to the ground, feigning to be dead or wounded, and had himself borne into the town. But he returned at once to the fray and so wrought that the English knew him yet living to their great injury and displeasure.” (J.S.O.105)

Or, again, there is the episode of the Christmas truce:

“Christmas Day were given and granted truces on one side as on the other from nine o’clock in the morning until three o’clock in the afternoon. And during this time, Glasdale and other lords of England requested of the Bastard of Orleans and of the lord of Saint-Sévère, Marshal of France, that they might have a note of high minstrelry (haut menetriers), trumpets and clarions, which was granted them. And they played the instruments quite a long time, making great melody. But as soon as the truces were broken (i.e. over), each fell again on guard.” (J.S.O.105)

And the days succeeded each other and brought the people none but bad news: their reserves of victuals were diminishing and they began to feel the pinch of famine. Thus, every arrival of fresh victuals was noted in the Journal of the Siege:

“The 3rd January arrived before Orleans one hundred and fifty-four swine large and fat, and four hundred sheep, and passed these cattle in by the Saint-Loup gate at which the people were right joyful, for they came at need.” (J.S.O.108)

The sorties which were attempted did not succeed:

“Saturday fifteenth day of January, about eight o’clock at night, sallied out of the city the Bastard of Orleans, the lord of Saint-Severe and messire Jacques de Chabannes, accompanied by many knights, esquires, captains and citizens of Orleans, and thought to charge upon a part of the army at Saint-Laurent. . . .” (A fortified islet in the Loire off Orleans.) “. . . But the English perceived it and cried the alarm among their troops whereby they were armed, so that there was a great and hard affray. At last the French retired for the English were coming out in full strength.” (J.S.O.110)

And above all there was the disastrous February 12, 1429, the “day of the herrings”. The English were bringing into their camp a convoy of victuals composed chiefly of barrels of salt herring, since it was Lent, the day being the eve of Brandons, first Sunday in Lent. Moreover, salt herring was, at that time, a staple food. The Bastard of Orleans, the Constable John Stuart, and other knights, joined by the count of Clermont and his troops, decided to attempt an assault against the convoy:

“Many knights and esquires of the lands of England and France, accompanied by fifteen hundred combatants, as English, Picards, Normans and people of diverse other countries, were bringing about three hundred carts and small carts” (possibly hand barrows), “laden with victuals, and with much war gear as canons, bows, bundles, arrows and other things, taking them to the other English who were maintaining the siege of Orleans. But when they knew by their spies the countenance of the French and learned that their intention was to attack them, they enclosed themselves (by) making a park [sic] with their carts and pointed stakes by way of barriers . . . and put themselves in good order of battle, there waiting to live or die; for to escape they had scarcely hope, considering their small number against the multitude of French who were all come together by a common accord, and concluded that none would dismount except the archers and baggage bearers* . . .”

However, the French Captains and the Constable of Scotland, who had joined forces with them, were unable to agree as to strategy. The battle opened in a tentative manner while they waited for the Count of Clermont, who kept sending messages asking that the enemy should not be engaged until he had brought up his reinforcements.

“So that, between two and three o’clock in the afternoon, the French archers drew near to their adversaries, of whom some had already come out of their park” [sic: say, laager] “. . . whom they forced to withdraw hastily. . . . Those who were able to escape went back inside their fortification with the rest. Now, when the Constable of Scotland saw that they had held themselves thus shoulder to shoulder in their ranks, without showing any wish to come out, was he too wishful to attempt to assail them, so much so that he disobeyed the order which had been given to all that none should dismount, for he began to assault without waiting for the others and, at his example, to help him, dismounted likewise the Bastard of Orleans . . . and many other knights and esquires with about four hundred combatants. . . . But little did it avail them, for, when the English saw that the great battle” (i.e., the main body) “which were quite far off, came on timidly (or slowly), and joined not with the Constable, they charged out swiftly from their park and struck among the French who were on foot, and put them to rout and flight. . . . More than that, the English, not sated with the slaughter that they had done on the place, before their park, spread themselves swiftly over the fields, chasing the foot soldiers, so much so that at least twelve of their standards were to be seen far from each other in diverse places. Therefore, La Hire, Poton* and several other valiant men who were making off so shamefully, rallied to the number of sixty or eighty combatants and struck at the English who were thus scattered, so that they killed many. And certainly had all the other French turned about as they did, the honour and profit of the day would have been with them. . . . From this battle escaped among others the Bastard of Orleans, albeit at the beginning he was wounded by an arrow in the foot: two of his archers dragged him with great difficulty out of the press, put him on a horse and thus saved him. The Count of Clermont, who that day had been dubbed knight, and all his great army, never even pretended to succour their companions, as much because they had dismounted (to fight) on foot against the general agreement, as because they saw them almost all killed before their eyes. But when they saw that the English were the masters, they set out towards Orleans; in which they did not honourably, but shamefully.” (J.S.O.120–124)

This inglorious day was also the last attempt to deliver the town before Joan’s arrival. The count of Clermont hastened to withdraw his troops (18 February). After which only Jean, the Bastard, later Count of Dunois, and the Marshal Saint-Sévère, with their men, were left to defend the town. It was at this point that the citizens of Orleans, feeling themselves abandoned, sent an embassy to the Duke of Burgundy imploring him, in the name of his kinsman Charles, Duke of Orleans, still a prisoner in England, to do something for them. According to chroniclers, Philippe the Good is supposed to have asked the regent Bedford that Orleans be given into his keeping, and neutralised. Bedford refused, saying—still according to the chroniclers—“That he would be very angry to have beaten the bushes that others might take the birds.” Philippe the Good, discontented with this answer, withdrew his troops from the force besieging Orleans.

Nevertheless the siege continued and the Journal now mentions none but insignificant supplies reaching the town:

“Friday 4 March, twelve horses laden with wheat, herrings and other victuals.

Sunday the 6th, seven horses laden with herrings and other victuals.

The Tuesday following, nine horses laden with victuals”—etc., showing to what extremities the inhabitants were reduced. The town was, in fact, so closely invested that only a single issue remained open: the Bourgoyne gate opening on to the old Roman road on the right bank of the Loire, that is in the direction of the zone controlled by the English.

Numerous, subsequently, were those citizens of Orleans who bore witness to their anguish during those interminable days: thirty-six of them were to give evidence on the single day of March 16, 1456, during the Trial of Rehabilitation; and what they said may be summed up as follows:

“The inhabitants and citizens found themselves squeezed in such necessity by the besieging enemies that they knew not whom to have recourse to for a remedy, excepting (or, unless it be) to God.” (R.139)

It was at this point that news reached these same inhabitants and citizens that a young girl had gone to the King of France, saying that she was sent by the King of Heaven to recover his kingdom for him. Obviously if we are to get some idea of the effect produced, we must enter into the general mentality of the period. Everybody at that time—or let us say almost everybody, for who will ever be able to estimate individual adherences to the general beliefs?—believed in God, and in a God who was master of all eventualities and could, therefore, intervene at will to make the unexpected happen: in other words, everyone believed in miracles. Furthermore, in the kingdom’s state of disorganisation, and in view of the Orleanais’ feeling that they had been abandoned, there could be no hope excepting in a miracle.

The Bastard of Orleans—that same brilliant captain who, two years before, had forced the enemy to raise the siege of Montargis—although his honour as a soldier was engaged, since he was in command of the defence of Orleans, was, when giving his evidence, foremost in declaring that all Joan’s acts seemed to him, in the event, “divinely inspired”. In any case, as soon as he heard of her, he sent to seek more information about her.

Jean, Bastard of Orleans: “I was in Orleans, at that time besieged by the English, when certain rumours circulated according to which had passed through the town of Gien a young girl, the Maid so-called, assuring that she was on her way to the noble Dauphin to raise the siege of Orleans and to take the Dauphin to Rheims that he might be crowned. As the city was in my keeping, being Lieutenant-General in the matter of warfare, for more ample information in the matter of this maid, I sent to the King the Sire de Villars, Seneschal of Beaucaire, and Jamet du Tillay who later became bailiff of Vermandois. Returned from their mission to the King they told me, and said in public, in the presence of all the people of Orleans who much desired to know the truth concerning the coming of this Maid, that they themselves had seen the said maid arrive to find the King in Chinon. They said also that the King, in the first instance, was not willing to receive her, but that she remained during two days, waiting to be allowed to enter the royal presence. And this although she said and repeated that she was come to raise the siege of Orleans and to conduct the noble Dauphin to Rheims that he be there consecrated, and although she demanded immediately a company of men, horses and arms.

“A space of three weeks or a month being passed, time during which the King had commanded that the Maid be examined by certain clerks, prelates and doctors of theology on her doings and sayings in order to know if he could in all surety receive her, the King called together a multitude of men to force some victuals into the city of Orleans. But, having gathered the opinion of the prelates and doctors—to wit, that there was no evil in this Maid—he sent her, in company with the lord archbishop of Rheims, then Chancellor of France (Regnault de Chartres), and of the lord de Gaucourt, now grand master of the king’s household, to the town of Blois wherein were come together those who led the convoy of victuals, to wit the lords de Rais and de Boussac, Marshal of France, with whom were the lords de Culant, Admiral of France, La Hire, and the lord Ambroise de Loré, since become Provost of Paris, who all together with the soldiers escorting the convoy of victuals and Joan the Maid, came by way of the Sologne in good military order (en armée rangée) to the river Loire directly and as far as the church called Saint Loup in which were numerous English forces.” (R.127–129)

It was, in fact, at Blois that the army which the Dauphin had, at Joan’s instance, decided to raise, was concentrated. The Duke of Alençon told how he had been entrusted with the preparation of this expeditionary force:

Jean d’Alençon: “The King sent me to the Queen of Sicily” (Yolande of Aragon, Charles VII’s mother-in-law) “to get together the victuals to be taken to Orleans for moving the army there. And there I found the lord Ambroise de Loré and a lord Louis whose other name I no longer recall who had prepared the provisions. But there was need of money, and to have money for these victuals I returned to the King and notified him that the victuals were ready and that it remained only to give the money for these victuals and for the soldiers. Then the King sent someone to deliberate of the money needful to conclude all this, so that the supplies and the soldiers were ready to go to Orleans to attempt to raise the siege if that was possible.” (R.148)

This was confirmed by the man whom Charles VII was to appoint as his official chronicler, Jean Chartier, a monk of Saint-Denis:

“Were laden in the town of Blois many carts and small carts (chars et charettes) of wheat and were taken great plenty of beeves, sheep, cows, swine and other victuals, and Joan the Maid set out as also the captains straight towards Orleans by the Sologne way. And lay one night in the open and on the morrow came Joan the Maid and the captains with the supplies before the town of Orleans.”

Properly to understand the order of march and route adopted it is necessary to consider the English strategic positions before Orleans (see map, p. 71). As they had concentrated on fortifying the approaches to the bridge and had surrounded the west of the town with a series of forts, only the Bourgogne* Gate remained, as we have seen already, open to the east. Consequently the captains made a detour so as to reach Orleans on its eastern side, the side least exposed to danger. But this was hardly likely to satisfy Joan, anxious as she was to fight.

The Bastard of Orleans: “As the King’s army and the soldiers escorting the convoy did not seem to me, any more than to the other lords-captains, sufficient to defend and conduct the supplies into the city, the more so in that there was need of boats and rafts which it would have been difficult to procure to fetch the supplies, for it was necessary to go upstream against the current and the wind was absolutely contrary, then Joan spoke to me these words which follow: ‘Are you the Bastard of Orleans?’ I answered her: ‘Yes, I am so and I rejoice at your coming.’ Then she said to me: ‘Did you give the counsel that I should come here, to this side of the river, and that I go not straight there where are Talbot and the English?’ I answered that myself and others wiser had given this counsel, thinking to do what was best and safest. Then Joan said to me: ‘In God’s name, the counsel of the Lord your God is wiser and safer than yours. You thought to deceive me and it is yourself above all whom you deceive, for I bring you better succour than has reached you from any soldier or any city: it is succour from the King of Heaven. It comes not from love of me but from God himself who, at the request of Saint Louis and Saint Charlemagne, has taken pity on the town of Orleans, and will not suffer that the enemies have the bodies of the lord of Orleans and his town.’ Forthwith and as in the same moment, the wind which was contrary and absolutely prevented the boats from moving upstream, in which were laden the victuals for Orleans, changed and became favourable. Forthwith I had the sails hoisted, and sent in the rafts and vessels. . . . And we passed beyond the Church of Saint-Loup despite the English. From that moment I had good hope in her, more than before; and I then implored her to consent to cross the river of Loire and to enter into the town of Orleans where she was greatly wished for.” (R.129)

After having hesitated a little to leave the main body of the expeditionary force, Joan agreed to enter Orleans with him.

“Then Joan came with me, bearing in her hand her standard which was white and upon which was the image of Our Lord holding a fleur-de-lys in his hand. And she crossed with me and La Hire the river of Loire, and we entered together into the town of Orleans.”

He added: “For all that” (i.e., for these reasons), “it seems to me that Joan and also what she did in warfare and in battle was rather of God than of men; the change which suddenly happened in the wind, after she had spoken, gave hope of succour, and the introduction of supplies, despite the English, who were in much greater strength than the royal army.” (R.131)

Jean d’Aulon: “After it came to the knowledge of my lord de Dunois, whom then was called my. lord Bastard of Orleans, who was in the city to preserve and keep it from the enemies, that the Maid was coming, he rallied together a number of soldiers to go out to meet her, as La Hire and others, and to this end and the more safely to bring and conduct her into the city, this lord and his men got into a boat and by the river of Loire went to meet her about quarter of a league and there found her.” (R.157)

The Journal of the Siege recounts in detail Joan’s entry into the town on the Friday evening, April 29, 1429: “The Friday following twenty-ninth of the same month, came into Orleans certain news that the King was sending by the Sologne way victuals, powder, canon and other equipments of war under the guidance of the Maid, who came from Our Lord to re-victual and comfort the town and raise the siege—by which were those of Orleans much comforted. And because it was said that the English would take pains to prevent the victuals, it was ordered that all take up arms throughout the city. Which was done.

“This day also arrived fifty foot soldiers equipped with guisarmes and other war gear. They came from the country of Gatinais where they had been in garrison.

“This same day there was a great skirmish because the French wished to give place and time for the victuals to enter, which were brought to them. And to keep the English busy elsewhere, they went out in great strength, and went running and skirmishing before Saint Loup d’Orleans and engaged them so closely that there were many dead, wounded and taken on both sides, and so that the French bore into the city one of the English standards. While this skirmish was making, entered into the town the victuals and the artillery which the Maid had brought as far as Checy. To meet her went out to that village the Bastard of Orleans and other knights, esquires and men of war from Orleans and elsewhere, right joyful at her coming, who all made her great reverence and handsome cheer (i.e., right welcome) and so did she to them; and they concluded all together that she should not enter into Orleans before nightfall, to avoid the tumult of the people. . . . At eight o’clock, despite all the English who never attempted to prevent it, she entered, armed at all points, riding upon a white horse; and she caused her standard to be borne before her, which was likewise white, on which were two angels, holding each a fleur-de-lys in their hands; and on the pennon was painted an annunciation (this is the image of Our Lady having before her an angel giving her a lily).

She entered thus into Orleans, having on her left hand the Bastard of Orleans very richly armed and mounted, and after came many other noble and valiant lords, esquires, captains and men of war, and several from the garrison, and likewise some burgesses of Orleans who had gone out to meet her. On the other hand came to receive her the other men of war, burgesses and matrons of Orleans, bearing great plenty of torches and making such rejoicing as if they had seen God descend in their midst; and not without cause, for they had many cares, travails and difficulties and great fear lest they be not succoured and lose all, body and goods. But they felt themselves already comforted and as if no longer besieged, by the divine virtue* which they were told was in this simple maid, who looked upon them all right affectionately, whether men, women, or little children. And there was marvellous crowd and press to touch her or the horse upon which she was. So much so that one of those bearing a torch drew so near to her standard that the pennon took fire. Wherefore she struck spurs to her horse and turned him right gently towards the pennon and extinguished the fire of it as if she had long served in the wars; which thing the men-at-arms held a great marvel and the burgesses of Orleans likewise who bore her company the whole length of their town and city, manifesting great joy, and by way of a very great honour, led her all to the near neighbourhood of the Regnard Gate, into Jacques Boucher’s great house (hotel) who was then Treasurer to the Duke of Orleans, where she was received with great joy, with her two brothers and two gentlemen and their body-servants who were come with them from the country of Barrois.”

Both in the Journal of the Siege and in the depositions of the Rehabilitation Trial, we can follow, day by day, the events which followed in Orleans during a week which was to be decisive.

Saturday, April 10th. No notable event. Much against her will Joan had to resign herself to wait, the other captains-at-war being of opinion that the enemy should not be engaged until the rest of the army, which had remained at Blois, had reached Orleans.

Louis de Coutes: “Joan went to see the Bastard of Orleans and spoke to him, and on her return she was in great anger; for, said she, he had decided that on that day they would not go out against the enemy. However, Joan went to a boulevard which the King’s soldiers were holding against the English boulevard, and there she spoke with the English who were in the other boulevard, telling them in God’s name to withdraw that otherwise she would drive them out. And one called the Bastard of Granville spoke many insults to Joan, asking her if she expected them to surrender to a woman, calling the French who were with Joau miscreant pimps.” (R.170)

“When evening fell, Joan went to the boulevard of the Belle Croix on the bridge and thence spoke to Classidas (Glasdale) and to the other English who were in the Tourelles and told them that if they would yield themselves at God’s command (de par Dieu) their lives were safe. But Glasdale and those of his company answered basely, insulting her and calling her ‘cow-girl’, shouting very loudly that they would have her burned if they could lay hands on her. At which she was much enraged and answered them that they lied, and that said, withdrew into the city.” (J.S.O.155)

Sunday, May 1st. Still nothing happened. The Sunday truce was generally observed. On that day, in any case, the Bastard of Orleans left the town to go and fetch the reinforcements massed at Blois.

“That day rode about the city Joan the Maid, accompanied by many knights and esquires because those of Orleans wanted so greatly to see her that they almost broke down the door of the mansion where she was lodged, to see her; there was such a press of townspeople in the streets she passed through that with great difficulty did she pass, for the people could not weary of seeing her, and it seemed to all a great marvel how she could sit her horse with such ease and grace (si gentiment) as she did. And in sooth, she bore herself as highly in all ways as a man of arms who had followed the wars since his youth would have been able to.” (J.S.O.155)

Monday, May 2nd: Still nothing. It is self-evident that in the absence of the Bastard of Orleans, charged with the city’s defence, Joan could not and would not undertake any operations.

Tuesday, May 3rd: Still nothing, unless it be what the town’s account books reveal. “For those who bore the torches in the procession of May 3rd last, being present Joan the Maid and other war chiefs, to implore Our Lord for the deliverance of the town of Orleans, 2 sous parisis.”

And again, these details, at once typical and touching: “To Raoulet de Recourt, for a shad presented to the Maid the 3rd May—20 sous parisis. To Jean le Camus, for a gift to three companions (friends) who had come to see Joan and had not the means to eat—4 sous parisis.” (q. v. 259)

Wednesday, May 4th. Dunois’ return with the reinforcements is heralded.

Jean d’Aulon: “As soon as she knew they were come and that they were bringing the others that they went to seek for the reinforcement of the city, hastily the Maid sprang to horse and, with some of her men, went out to meet them and to strengthen and succour them if need there should be.

“Within sight and knowledge of the enemies, entered the Maid, Dunois, the marshal (Boussac) La Hire, I who speak and our men, without any impediment whatsoever.

“That same day, after dinner came my lord of Dunois to the Maid’s lodging where she and I had dined together. And speaking to her his lord of Dunois told her that he knew it fortrue by trustworthy men, that one Falstaff (John Falstaff, captain of freebooters), an enemy captain, would soon be coming to the besieger enemies, both to bring them succour and reinforce the army and to revictual them, and that he was already at Janville. At these words the Maid was right rejoiced, as it appeared to me, and she spoke to my lord of Dunois these words, or similar ones: ‘Bastard, Bastard, in God’s name I command thee that, as soon as thou knowest that Falstaff is come, thou shalt make it known to me, for if he pass without my knowing of it, I promise thee I will have thy head taken off!’ To which answered the lord of Dunois that she doubt not, for he would indeed make it known to her.

“After these exchanges, I who was weary and fatigued cast myself down on a mattress in the Maid’s chamber, to rest a little. And likewise did she, with her hostess, on another bed, to sleep and rest. But while I was beginning to take my rest, suddenly the Maid rose from the bed, and making a great noise, roused me. At that I asked her what she wanted. She answered me: ‘In God’s name my counsel has told me to go out against the English and I know not whether I must go against their fortification (bastide) or against Falstaff who is to revictual them.’ Upon which I arose at once and, as swiftly as I could, put the Maid into her armour.” (R.159)

Louis de Coutes also tells how Joan, after having slept a little, “Came down again and said to me these words: ‘Ah, bleeding boy, you told me not that the blood of France was spilling!’ while urging me to go fetch her horse. In the interval she had her armour put on by the lady of the house and her daughter, and when I came back from saddling and bridling her horse, I found her ready armed; she told me to go and fetch her standard which was upstairs and I handed it to her through the window. After having taken her standard, Joan hastened, racing towards the Burgundy Gate. Then the hostess told me to go after her, which I did. There was at that time an attack or a skirmish over towards Saint-Loup. It was in this attack that the boulevard was taken, and on her way Joan encountered many French wounded, which saddened her. The English were preparing their defence when Joan came in haste at them, and as soon as the French saw Joan, they began to shout (? cheer) and the bastion and fortress of Saint-Loup were taken.”

Jean Pasquerel: “I recall that it was on the eve of Ascension of Our Lord, and there were many English killed. Joan lamented much, saying that they had been killed without confession, and she wept much upon them and at once confessed herself to me, and she told me publicly to exhort all the soldiers to confess their sins and to give thanks to God for the victory won; if not she would stay not with them but would leave them. And she said also, on that vigil of the Ascension of the Lord, that within five days the siege of Orleans would be raised and that there would linger no more English before the city. . . . That day, at evening, being returned to her lodging, she told me that on the morrow, which was the day of the Feast of the Ascension of the Lord, she would make no war nor take up arms, out of respect for the Feast. And that day she wished to confess and to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist, which she did. And that day she commanded that no man should dare on the morrow go out of the city to assault or attack if he had not first been to confession. And let them take care that women of ill-fame follow not the army, for it was for those sins that God allowed the war to be lost. And it was done as Joan had commanded.” (R.80)

Thursday, May 5th. Joan sent to the English the third and last letter of summons. We do not have the text of the second unless it did no more than repeat the letter already quoted.

“You, Englishmen, who have no right in this Kingdom of France, the King of Heaven orders and commands you through me, Joan the Maid, that you quit your fortresses and return into your own country, or if not I shall make you such babay that the memory of it will be perpetual. That is what I write to you for the third and last time, and shall write no more. Signed: Jhesus-Maria, Joan the Maid.” “For my part I shall have sent you my letters honourably, but for yours you detain my messengers, for you have held my herald named Guyenne. Be so good as to send him back (veuillez le renvoyer) and I will send you some of your people taken in the fortress of Saint-Loup, for not all were dead there.”

Jean Pasquerel: “She took an arrow, tied the letter with a thread to the end of the arrow and ordered an archer to shoot the arrow to the English, crying ‘Read, it is news!’ The English received the arrow with the letter and read it. And having read it they began to utter great shouts, saying, ‘News of the Armagnacs’ whore!’ At these words Joan began to sigh and to weep copious tears, calling the King of Heaven to her aid. And thereafter was she consoled, as she said, for she had had news of her Lord. And that evening, after dinner, she ordered me to rise on the morrow earlier than I had done on Ascension Day, and that she would confess herself to me very early in the morning, which she did.”

Friday, May 6th. Jean Pasquerel: “That day, Friday, the morrow of the Feast of the Ascension, I rose early in the morning and heard Joan’s confession and sang mass before her and her men in Orleans. Then they went out to the assault which lasted from morning until evening. And that day was taken the fortress of the Augustins, by grand assault; and Joan, who was accustomed to fast on Fridays, could not fast that day, for she had been too much fatigued and she dined.” (R.181)

Yet this assault seems to have been a surprise (not a meditated) attack, if we are to believe the testimony given by Simon Charles: “Of what was done at Orleans I know nought but by hearsay, for I was not present there, but there is one thing which I heard said by the lord de Gaucourt when he was at Orleans: it had been decided by those who had charge of the King’s men that it was not advisable to make assault nor attack on the day when the bastion of the Augustins was taken, and this lord de Gaucourt was charged to guard the gates so that none should go out. Joan, however, was ill-content with that. She was of opinion that the soldiers should go out with the townsmen and attack the bastion. Many of the men of war and townsmen were of the same opinion. Joan said to this sire de Gaucourt that he was a bad man. ‘Whether you will or not, the fighting men will come and will obtain what they have elsewhere obtained.’ And against the will of the lord de Gaucourt, the soldiers who were in the town went out and made an attack to invade the Augustins bastion which they took by storm. And from what I have heard tell by the sire de Gaucourt, he was himself in great peril.” (R.104)

Jean d’Aulon: “The Maid and her men went out of the city in good order to go and assail a certain bastion before the city, called the bastion of Saint-Jean-le-Blanc. To do this, as they saw that they could not goodly (well) reach this bastion by land given that the enemy had built another and very strong at the foot of the city bridge, so that it was impossible for them to pass that way, it was resolved between them to cross to a certain isle in the river Loire and that there they would assemble to go out and make their attack on the bastion of Saint-Jean-le-Blanc. And, to cross the other arm of the river Loire, they sent for two boats of which they made a bridge to go to the bastion.

“That done, they went towards the bastion which they found all disordered because the English who were in it no sooner saw the French coming than they went away and withdrew into another stronger and bigger bastion called the bastion of the Augustins. The French, seeing that they were not strong enough to take this bastion, it was resolved that they would return from it without doing anything.

“While the French were retreating from the bastion of Saint-Jean-le-Blanc to return to the island, the Maid and La Hire both crossed, each with a horse in a boat, from the other side of this island, and mounted these horses as soon as they were across, each with lance in hand, and when they perceived that the enemies were coming out of the bastion to charge their men, at once the Maid and La Hire, who were always before them to guard them, couched their lances and were the first to strike among the enemies. Thereupon the others all followed them and began to strike at the enemy in such fashion that by force they drove them to retire and enter again into the bastion of the Augustins. . . . Very bitterly and with much diligence they assailed it from every side so that in a little while they gained and took it by storm; and there were killed or taken the greater part of the enemies, and those who could escape retired into the bastion of the Tourelles at the foot of the bridge. And thus won the Maid, and those who were with her, victory over the enemies upon that day and was the great bastion taken, and there remained the lords and their men with the Maid, all that night.” (R.161–163)

The taking of this bastion of the Augustins was an important feat of arms; the bastion was the most considerable of those which covered the Tourelles, the fortification commanding the approach to the bridge. The Orleanais were quick to realise the value of the achievement, a fact confirmed by the Journal of the Siege: “Those of Orleans were most diligent in bearing all night long bread, wine and other victuals to the men of war maintaining the siege.”* (J.S.O.159)

Jean Pasquerel: “After dinner came to Joan a valiant and notable knight whose name I no longer recall. He told Joan that the King’s captains and soldiers had held counsel together and that they saw they were but few by comparison with the English and that God had shown them great mercies in the satisfactions already obtained, adding: ‘Considering that the town is well provided with victuals, we might well keep the city while awaiting help from the King, and it does not seem advisable to the council that the soldiers go out tomorrow!’ Joan answered him: ‘You have been at your counsel and I at mine; and know that my Lord’s counsel will be accomplished and will prevail and that that (other) counsel will perish.’ And addressing herself to me who stood at her side: ‘Rise tomorrow early in the morning and earlier than you did to-day and do the best that you can; be always at my side, for tomorrow I shall have much to do, and more than I ever had, and tomorrow the blood will flow out of my body above my breast.’ ” (R.181–182)

Saturday, May 7th. Jean Pasquerel: “On the morrow, Saturday, I rose early and celebrated mass. And Joan went out against the fortress of the bridge where was the Englishman Classidas. And the assault lasted there from the morning until sunset. In this assault, after the morning meal, Joan, as she had predicted, was struck by an arrow above the breast, and when she felt herself wounded she was afraid and wept, and was consoled as she said. And some soldiers, seeing her so wounded, wanted to apply a charm to her wound, but she would not have it, saying: ‘I would rather die than do a thing which I know to be a sin or against the will of God.’ And that she knew well that she must die one day, but knew not when or how or at what time of the day. But if to her wound could be applied a remedy without sin, she was very willing to be cured. And they put on to her wound olive oil and lard. And after that had been applied, Joan made her confession to me, weeping and lamenting.” (R.182)

The Bastard of Orleans: “The assault lasted from the morning until eight o’clock of vespers, so that there was hardly hope of victory that day. So that I was going to break off and wanted the army to withdraw towards the city. Then the Maid came to me and required me to wait yet a while. She herself, at that time, mounted her horse and retired alone into a vineyard, some distance from the crowd of men. And in this vineyard she remained at prayer during one half of a quarter of an hour. Then she came back from that place, at once seized her standard in hand and placed herself on the parapet of the trench, and the moment she was there the English trembled and were terrified. And the king’s soldiers regained courage and began to go up, charging against the boulevard without meeting the least resistance.” (R.132)

Jean d’Aulon: “They were before that boulevard from morning until sunset without being able to take nor win it. And the lords and captains being with her, seeing that they could not well win it that day, considering the time, that it was very late, and also that all were very weary and tired, it was concluded between them to sound the retreat of the army, which was done, and as the clamour of the trumpets sounded each would retire for that day. In beating this retreat, he who bore the Maid’s standard and held it still erect before the boulevard, being weary and tired, passed the standard to one named Le Basque, who was the lord de Villard’s man. And because I knew this Basque to be a valiant man and that I feared lest because of this retreat the worst befall . . . it occurred to me that if the standard was driven forward by reason of the great ardour which I knew to be among the men of war who were there, they might by this means win the boulevard. So I asked Le Basque, if I entered and went to the foot of the boulevard, if he would follow me. He told me and promised me that he would do so. Then I went into the trench and as far as the foot of the boulevard ditch (moat, trench), covering myself with my shield for fear of stones, and left my comrade on the other side, for I thought he would be following close in my footsteps. But when the Maid saw her standard in the hands of Le Basque and thought that she had lost it, for he who bore it had gone down into the trench, she went and seized the end of the standard in such manner that he could not carry it away, crying ‘My standard, my standard!’ and waved the standard in such fashion that I imagined that so doing the others would think that she was making them a sign. Thereupon I shouted, ‘Ah! Basque, what didst thou promise me?’ Then Le Basque tugged so at the standard that he tore it from the Maid’s hands and so doing came to me and raised the standard. This occasioned all who were of the Maid’s army to come together and to rally again, and with such bitterness assail the boulevard that a little time thereafter this boulevard and the bastion were taken by them and by the enemy abandoned; and thus went in the French to the city of Orleans by way of the bridge.” (R.163–164)

“No sooner had the attack recommenced than the English lost all power to resist longer and thought to make their way from the boulevard into the Tourelles, but few among them could escape, for the four or five hundred soldiers they numbered were all killed or drowned, excepting some few whom were taken prisoners, and these not great lords. And thinking to save themselves the bridge broke under them, which was great disorder to the English forces and great pity for the valiant French, who for their ransom might have had much money (grand finance).” (J.S.O.162)

Jean Pasquerel: “Joan returned to the charge, crying and saying: ‘Classidas, Classidas, yield thee, yield thee to the King of Heaven; thou hast called me “whore”, me; I take great pity on thy soul and thy people’s!’ Then Classidas, armed (as he was) from head to foot, fell into the river of Loire and was drowned. And Joan, moved by pity, began to weep much for the soul of Classidas and the others who were there drowned in great numbers. And that day all the English who were beyond the bridge were taken or killed.” (R.182)

Jean d’Aulon: “The same day I had heard the Maid say, ‘In God’s name, we shall this day enter the town by the bridge.’ And that done, withdrew the Maid and her men into the town of Orleans where I had her cared for, for she had been wounded by an arrow in the charge.

“They (the army and people of Orleans) made great rejoicing and praised Our Lord for this great victory which He had given them; and right was it that they should do so, for it is said that this assault, which lasted from morning until sunset, was so greatly fought in both attack and defence, that it was one of the grandest feats of arms that there had been for a long time before. . . . And the clergy and people of Orleans sang devoutly Te deum laudamus and caused all the bells of the city to be pealed, most humbly thanking Our Lord for that glorious divine consolation. And made great joy on all sides, giving marvellous praises to their valiant defenders, and above all others to Joan the Maid. She remained that night, and the lords, captains and men-at-arms with her, in the field, both to guard the Tourelles thus valiantly captured, as to watch lest the English, over by Saint-Laurent, came out, trying to succour or avenge their companions. But they had not the heart for it.” (J.S.O.163)

The Bastard of Orleans: “Thus the bastion was taken, and I came in again, as also the Maid, with the other French, into the city of Orleans, in which we were received with great transports of joy and piety. And Joan was taken to her lodgings that her wound might be dressed. When the dressing had been done by the surgeon, she took her meal, eating four or five toasts washed down with wine mixed with much water, and took no other nourishment or drink during all that day.” (R.133)

Sunday, May 8th: “The following morning, Sunday and eighth day of May, this same year 1429, the English demolished their bastion . . . and raising their siege ranged themselves in battle. . . . Whereupon the Maid . . . and many other valiant men of war and citizens went out of Orleans in great strength and placed and ranged themselves before them in ordered battle. And at some points were very near to each other for the space of an hour without touching each other. Which thing the French submitted to with a very ill grace, obeying the will of the Maid, who commanded and forbade that for love and honour of the holy Sunday, they begin not the battle nor make assault on the English; but if the English attacked them let them defend themselves strongly and boldly and let them have no fear, and they would be the masters. The hour being passed, the English set off and marched away, well ordered in their ranks, into Meung-sur-Loire, and raised and utterly abandoned the siege which they had maintained before Orleans since the twelfth day of October 1428 until that day. Nonetheless, they went not away nor got safely off with their baggage, for some from the city garrison pursued them and struck at the tail of their army in diverse assaults, so that they won from them great bombards, and canon, bows, arbalests (cross-bows) and other artillery . . . Meanwhile, entered to great rejoicing the Maid into the City of Orleans, and the other lords and men of war, in (the midst of) the very great exultation of all the clergy and people who all together gave humble thanks to Our Lord and well-deserved praises for the very great succours and victories which He had given them and against the English, ancient enemies of this kingdom. . . . That same day and on the morrow also, made very grand and solemn procession the Churchmen, lords, captains, men-at-arms and burgesses being and residing in Orleans, and visited the churches in great devoutness. And in all truth, although the burgesses had not been willing at first and before the siege began that any men of war enter their city, fearing lest they come to pillage them or be too hard masters, nonetheless did they afterwards allow in as many as would come, once they knew (realised) that they came only for their defence and bore themselves so valiantly in the face of their enemies; and they were with them very united for the defence of the city, and shared them out among themselves in their mansions (hotels) and fed them with all good things which God gave them, as familiarly as if they had been their own sons.” (J.S.O.164–167)

As for Joan herself, she was not really given a chance during the Trial of Condemnation to recall memories of Orleans. Quite obviously, her judge was anxious to avoid any mention of it. Her exploit had been altogether too resounding. She did, however, manage to tell, in a single phrase, what her conduct had been in the course of that exploit: “I was the first to place a scaling ladder on the bastion of the bridge.” (C.79)

Year fourteen hundred and twenty-nine

Came out again the sun.

Good times anew came with its shine

As long they had not done.

Long time did many who were apine

Live through: I was one,

But no more at aught now do I pine

When I see my want is won.*

L’an mil quatre cent vingt et neuf

Reprit a luire le soleil

Il ramène le bon temps neuf

Que l’on n’avait vu du droit œil

De longtemps, dont plusieurs en deuil

En vécurent: je suis de ceux

Mais plus de rien je ne me deuil

Quand ores vois ce que je veux.

These lines are probably the last which were written by the poetess Christine de Pisan, in 1429. She had withdrawn into a nunnery eleven years before—at the time of the English entry into Paris—and had written nothing since. If, in her old age, she now took up her pen again, it was to celebrate the incredible event which was changing the course of history and restoring confidence to the people of France.

Qui vit donc chose advenir

Plus hors de toute opinion

Que France, de qui mention

On faisait qu’à terre est tombée,

Soit par divine mission

De mal en si grand bien mué,

Et par tel miracle vraiment

Que, si chose n’était notoire

Et évident quoi et comment,

Il n’est homme qui le pût croire!

Chose est bien digne de mémoire

Que Dieu, par une vierge tendre

Ait ainsi voulu [chose voire (vraie)]

Sur France si grand grâce étendre. (Q. v, 3 and s.)

It is a fact that the extraordinary nature of the event had been fully realised. Even as late as the Trial of Rehabilitation the ordinary people of Orleans could hardly contain their enthusiasm as the victory was recalled. In a manuscript which was discovered in Quicherat’s time, in the Vatican library (Fonds de la reine de Suède No. 891), are to be found some details on the establishment of the famous feast and procession of May 8th which was to be celebrated every year thereafter in Orleans, and was not even dropped during the Terror; these details seem to have been given by an eye-witness of the raising of the siege who must have written down what he remembered in about 1460:

“My lord bishop of Orleans, with all the clergy and also by order of my lord of Dunois, brother of my lord the Duke of Orleans and with his counsel, and also the burgesses, labourers (churls) and inhabitants of Orleans, ordered to be formed a procession on May 8th and that each bear in it a torch and that they were to go as far as the Augustins and everywhere there had been fighting and that they should make station and propitious service, and prayers. And the twelve procurators of the town would each bear a candle in his hands, on which would be the town’s arms. . . . Thus should we be very devout in this procession especially such as are of Orleans, since they of Bourges-en-Berry (also) make a solemnity of it—but they take the Sunday after Ascension. And also several other towns make a solemnity of it, for if Orleans had fallen into the hands of the English, the rest of the kingdom would have been much harmed. . . . Everyone is required to go to the procession and to carry a burning torch in hand. The return is about the town by way of the church of Our Lady of Saint-Paul and there is given great praise to Our Lady and thence to Sainte-Croix, and there is the sermon and the Mass thereafter and also the vigils at Saint-Aignan: and on the morrow Mass is said for the dead.” (Q.v, 296–298)

The Orleans account books several times make mention of the expenses incurred by the town for this procession from as early as 1435:

“To Jacquet Lepretre, servant of the town of Orleans, for the purchase of twenty-three pounds of new wax, bought to remake the town’s torches and put with twenty-six pounds of old wax left from the said torches, for the solemnity of the procession of the Tourelles, held on the eighth day of May 1435, at a price of two sous ten deniers the pound . . . 62 sous four deniers. . . .

“To Jean Moynet, candle-maker, for the fashioning of the torches and candles and for the sticks* and for a torch (flambeau) given on the morrow of the said procession at a mass sung for the dead in the the church Monseigneur Saint-Aignan . . . 26 sous.” (Q.v, 308)

As for the prince whom Joan called the Dauphin, we know very precisely how he received the news of the event, by means of a circular letter which he was engaged in dictating to the “good towns” of the kingdom and of which the text was, fortunately for us, preserved by at least one of the recipient cities, to wit Narbonne. Other towns, like La Rochelle, only have a note of its receipt in their registers. It was dictated in three parts, between the evening of May 9th and dawn on the 10th when the messenger bringing the news of victory reached Chinon:

“From the King, dear and well-beloved, we believe that you have been informed of the continual diligence by us exercised to bring all succour possible to the town of Orleans long besieged by the English, ancient enemies of our kingdom, and the endeavours into which we have entered on diverse times, having always good hope in Our Lord that at length he would extend to it His mercy and would not permit that so notable a city and so loyal a people perish or fall into subjection to the said enemies. And for as much as we know that greater joy and consolation you, as loyal subjects, could not have than to hear announced good news, we make known to you that, by our Lord’s grace from which all proceeds, we have again caused to be revictualled in strength the town of Orleans twice in a single week, well and greatly, in the sight and knowledge of the enemies, without their being able to resist.

“And since then, to wit, last Wednesday, our people sent with the victuals, together with the men of the town, have assailed one of the enemy’s strongest bastions, that of Saint-Loup, the which, God aiding, they have taken and won by great assault which lasted four or five hours, and all the English having been killed who were inside it without any being dead of our people but two men only, although the English who were in the other bastions had come out in battle, seeming to offer combat, nevertheless when they saw our people come to meet them, they turned about hastily without daring to wait for them. . . . Since these letters written, there has come to us a herald about one hour after midnight, who has reported to us on his life that last Friday our aforesaid people crossed the river by boat at Orleans and besieged, on the Sologne side, the bastion at the end of the bridge and the same day won the fort of the Augustins. And on the Saturday likewise assailed the rest of the said bastion which was the boulevard of the bridge, where there were at least six hundred English fighting men under two banners and the standard of Chandos. And finally, by great prowess and valiance in arms, yet still by means of Our Lord’s grace, won all the said bastion and of it were all the English therein killed or taken. For that more than ever before must praise and thank our Creator, that in His divine clemency He has not forgotten us. And cannot sufficiently honour the virtuous acts and things marvellous which this herald who was present has reported to us and likewise the Maid who was always present in person at the doing of all these things. . . .

“And since then again, before the completion of these letters, have arrived with us two gentlemen who were at this work, who certify and confirm all, more amply than the herald, and from thence have brought us letters from the hand of the sire de Gaucourt. After that our men had last Saturday taken and demolished the bastion of the bridge end, on the morrow at dawn, the English who were in it, decamped and fled so hastily that they left their bombards, canons and artilleries, and the best part of their provisions and baggage.

“Given at Chinon, the tenth day of May. Signed: Charles.” (Q. v, 101–104)

Note here—as we shall have occasion to note again—that Charles VII showed himself very discreet touching the matter of Joan’s exploits. Among the people of his suite, however, were some who were more enthusiastic; among other evidence there is the famous letter of Alain Chartier, the poet, written to a foreign prince whom it has proved impossible to identify, at the end of July 1429, a copy of which is preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Chartier gives a swift résumé of what was known of the Maid’s origins, and tells how she came to the King’s court, and gives an account of the events which followed, up to the deliverance of Orleans. He concludes:

“Here is she who seems not to issue from any place on earth, but rather sent by Heaven to sustain with head and shoulders a France fallen to the ground. O astonishing virgin! worthy of all fame, of all praise, worthy of all the divine honours! Thou art the honour of the reign, thou art the light of the lily, thou art the splendour, the glory, not only of Gaul but of all Christians. Let Troy celebrate her Hector, let Greece pride herself upon Alexander, Africa upon Hannibal, Italy upon Caesar and all the Roman generals. France, though she count many of these, may well content herself with this Maid only. She (France) can pride herself and compare herself with these other nations for the honour of the ladies, and can even, if she so wish, set herself above them.” (Latin text in Q. v, 131–136)

Whereas Alain Chartier, full of enthusiasm though he was, kept strictly to the facts in his account of the essential event, that is the raising of the siege of Orleans in the extraordinary circumstances we have described, we cannot say as much for another personage, Perceval de Boulainvilliers, King’s Councillor and Seneschal of Berry. One of his letters has survived, addressed to the Duke of Milan, Philippe Maria Visconti, with whom he was in touch, having married the governor of Asti’s daughter. This letter implies in its author a taste for the anecdotal which drives him to seek the marvellous where it is not to be found. One can sense, as one reads it, that already there must have been old wives’ tales about Joan in circulation. It was natural enough: there is hardly a hero in history whom legend has not seized upon even in his lifetime. Boulainvilliers tells of her birth in Domremy, and it is he who gives us an exact date, which may be the true one, saying that she was born on the night of Epiphany, January 6th, adding that that night the cocks crowed at an unusual time, “Like heralds of a new joy” . . . which caused the people of the town to wake and wonder. A little later we have Joan, put in charge of the ewes, never losing a single one. When she played in the meadows with the other little girls her feet did not touch the ground, and she ran with such swiftness that one of her playmates cried, “Joan, I can see you flying above the ground” etc. etc. The writer then has a great deal to say about her apparitions, then gives an account of the succeeding episodes: Vaucouleurs, Chinon, Orleans—his letter being dated June 21st. Of more value to us are the details which Boulainvilliers gives on Joan’s physical appearance; for despite the exaggerated tone of the whole letter, these may be more or less true since he did probably see Joan. “This Maid,” he says, “has a certain elegance. She has a virile bearing, speaks little, shows an admirable prudence in all her words. She has a pretty, woman’s voice, eats little, drinks very little wine; she enjoys riding a horse and takes pleasure in fine arms, greatly likes the company of noble fighting men, detests numerous assemblies and meetings, readily sheds copious tears, has a cheerful face; she bears the weight and burden of armour incredibly well, to such a point that she has remained fully armed during six days and nights.” (Latin text in Q. v, 114–121)

The terms of this letter were to be recapitulated in a poem written some time later by a poet of Asti named Antonio.

It is, on the other hand, surprising that Charles, Duke of Orleans, himself a poet, whose town Joan had saved for him, never makes the slightest allusion to her in his poetry. But warfare, and in general the fortunes and misfortunes of the kingdom, do not in any case receive much attention from him. Reading his works, it is difficult to believe that they were composed by a man who was a prisoner-of-war for twenty-five years. His gratitude was expressed in the traditional way, that is by having made for Joan a “livery” bearing his arms. By an assignation bearing the date September 30, 1429, he approves and undertakes the cost of making this suit of clothes, the work having been put in hand in June by his treasurer at Orleans, Jacques Boucher:

“To the people of our accounts (exchequer) . . . we authorise (mander) you that the sum of thirteen golden crowns . . . which by our beloved and loyal treasurer general, Jacques Boucher, was paid and delivered in the month of June last to Jean Luillier, merchant, and Jean Bourgeois, tailor, residing at Orleans, for a robe and cloak which the men of our council had made and delivered to Joan the Maid in our town of Orleans, having consideration to the good and agreeable services which the Maid did for us at the encounter with the English, ancient enemies of my lord the king and of ourselves (this sum to be allowed in the accounts of our treasurer and deducted from his revenue). That is to say, to the said Jean Luillier, for two ells of fine Brussels vermillion cloth of which the said robe was made, eight crowns of gold; . . . and for one ell of deep green for the making of the huque, two crowns of gold; and to the said Jean Bourgeois for the making of the robe and huque, and for white satin, cendal (a silk material) and other stuffs, for the whole, one crown of gold.” (Q. v, 113)

So resounding was the exploit at Orleans that it rallied to Charles VII’s cause certain notabilities who had hitherto been hesitating to embrace it. For example, the Duke of Brittany sent a religious, his confessor, and a herald to congratulate him upon his victory; this fact is known to us by means of a register of accounts which was formerly preserved in the Nantes Archives of the Chamber of Accounts; and also from a German chronicle of the times, composed by the Emperor Sigismund’s treasurer, Eberhard of Windecken; this official had all the emperor’s official correspondence through his hands, and he made good use of it. It is he who tells how “the Duke of Brittany sent his confessor to the girl to question her whether it was by God that she was come to succour the King. The girl answered ‘Yes’. Then the confessor said: ‘If it be so, my lord the duke of Brittany is disposed to come to the King’s aid with his service’, and he called the duke her right lord. ‘He cannot come in his proper person’, he added, ‘for he is in a great state of infirmity, but he can send his eldest son with a great army.’ Then the girl said to the confessor that the duke of Brittany was not her right lord, for it was the King who was her right lord, and that the duke should not reasonably have waited so long to send his men to help the King with their services.” (German text and translation in Q. v, 498)

Nor was a note of comedy missing from the concert of praise: the capitouls, municipal councillors, of the city of Toulouse, then very embarrassed by the state of the city’s finances, decided, in the course of their meeting of June 2nd, to write to the Maid, “explaining to her the inconveniences of money changing and asking her what remedy to apply”. . . . Joan seemed to them to be a sort of magician whose abilities must be universal! In the same spirit, Bonne de Visconti, Duchess of Milan, wrote asking her to restore her to the possession of her duchy. And then there was the case of the Duke of Armagnac who wrote her a letter which was to be exploited by the judges at her Trial of Condemnation, asking her which of the three popes at that time claiming to be the rightful sovereign pontiff ought to be considered the true head of Christianity. The duke had an axe to grind; he had supported two anti-popes in succession and had been placed under an interdict by the legitimate pope, Martin V.

Furthermore, while the deliverance of Orleans had a tremendous importance for the French, its effect was no less great on the English and Burgundian side. Its extent can be measured by the fact that in the course of the following year, on May 3rd and December 12, 1430, two mandates were published “against the captains and soldiers, deserters terrified by the Maid’s enchantments”. These mandates were proclaimed in the name of the infant King of England by his uncle the Duke of Gloucester.

As for the Regent himself, John, Duke of Bedford, his feelings are known to us from a letter which he wrote in 1434, summing up events in France for his nephew the King of England:

“And alle thing there prospered for you, til thety me of the siege of Orleans taken in hand, God knoweth by what advis. At the whiche tyme, after the adventure fallen to the persone of my cousin of Salysbury, whom God assoille, there felle, by the hand of God, as it seemeth, a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadde beleve, and of unlevefulle doubte that thei hadde of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fais enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the nombre of youre people, there, but as well withdrowe the courage of the remenant in merveillous wyse, and couraiged youre adverse partie and ennemys to assemble hem forthwith in grete nombre.”

Clearly from the beginning of these events the English were desirous of attributing Joan’s victories to “enchantments and sorceries”. Which is what the judges at her trial tried to establish, though without success as we shall see.

As for the “foresworn Frenchmen” . . . or, as we should say nowadays, collaborators, their feelings are known to us by those of, among others, a man who can be taken as being thoroughly representative, to wit that “Bourgeois of Paris”, who was, in reality, a clerk of the University of Paris which Bedford had taken good care to pack with his creatures, and who wrote a Journal kept from day to day throughout the whole course of events. In 1429 he wrote as follows:

“There was then on the Loire a Maid, as she was called, who claimed to be a prophet and who said: ‘Such-and-such a thing will surely happen’. She was against the regent of France and his allies. It is said that despite the siege she entered into Orleans at the head of a host of Armagnacs with a great quantity of victuals, and that the English made no move, although she was at a bow-shot or two and despite so great a want of sustenance that one man had eaten three silver coins’ worth of bread at least at his meal. And those who preferred the Armagnacs to the Burgundians and to the regent of France said of her many other things: they affirmed that as a little child she kept the sheep and that the birds of the woods and fields came to her call to eat bread from her lap, as if tamed.

“In that time the Armagnacs raised the siege of Orleans from which they drove the English, then marched on Vendome which they took, it was said. This Maid in arms accompanied them everywhere, bearing her standard on which was inscribed only ‘Jesus’. It was said that she had told an English captain to abandon the siege with his troop otherwise would happen to them only ill and shame. And this captain had much insulted her, calling her, for example, a ribald woman and a whore. She answered that they would all depart swiftly despite themselves, but that he would no longer be there to see it and that a great part of his troop would likewise be killed. It was so for he drowned himself on the day of battle.” (The allusion is to William Glasdale.) (Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris de 1405 à 1449, Ed. J. Megret, p. 90)

The Burgundian chroniclers give a correct account of the facts touching the siege of Orleans, but do their best to run down Joan herself. We quote, as representative, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, a bastard of good family in the personal service of Philippe the Good, Duke of Burgundy, from 1430: