NATIONAL PARK MOVEMENT IN UTAH

SOUTHERN UTAH’S NATIVE AMERICANS

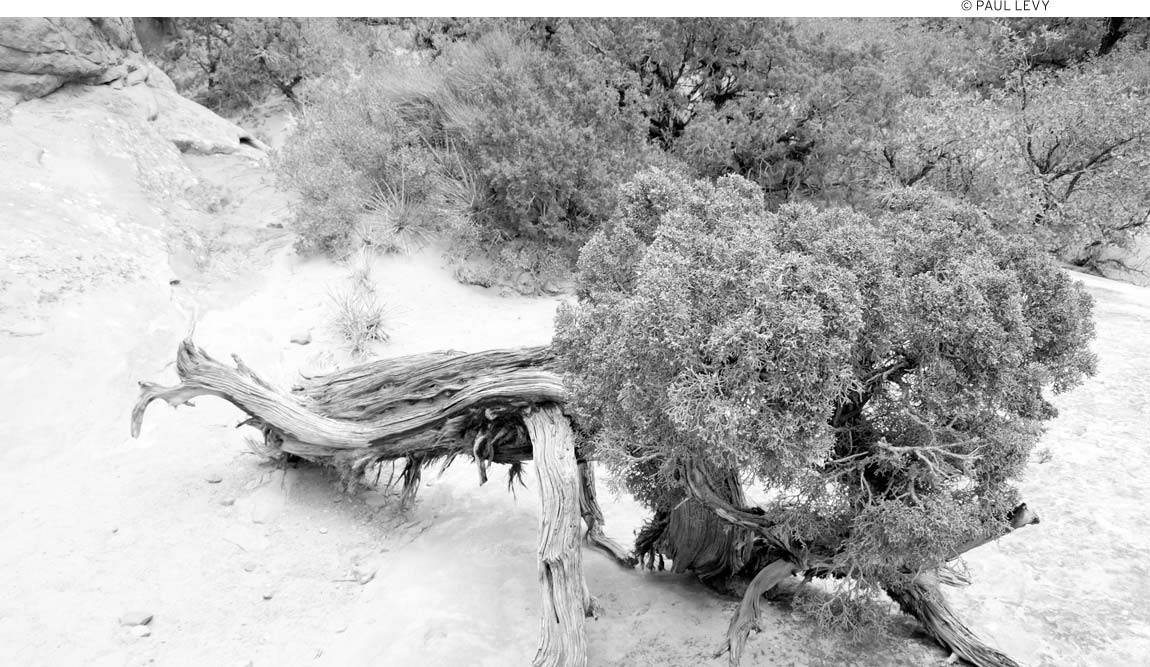

Southeastern Utah’s two national parks and its preserves of public land are all part of the Colorado Plateau, a high, broad physiographic province that includes southern Utah, northern Arizona, southwest Colorado, and northwest New Mexico. This roughly circular plateau, nearly the size of Montana, also contains the Grand Canyon, the Navajo Nation, and the Hopi Reservation.

Created by a slow but tremendous uplift, and carved by magnificent rivers, the plateau is mostly between 3,000 and 6,000 feet elevation, with some peaks reaching nearly 13,000 feet. Although much of the terrain is gently rolling, the Green and Colorado Rivers have sculpted remarkable canyons, buttes, mesas, arches, and badlands. Think of this area as a layer cake of rock that has been fractured by synclines, anticlines, and folds. Nongeologists can picture the rock layers as blankets on a bed, and then imagine how they look before the bed is made in the morning. This warping, which goes on deep beneath the earth’s surface, has affected the overlying rocks, permitting the development of deeply incised canyons.

Isolated uplifts and foldings have formed such features as the rock arches in Arches National Park, while the rounded Abajo and La Sal Mountains are examples of intrusive rock—an igneous layer that was formed below the earth’s surface and later exposed by erosion.

When you visit southeastern Utah, one of the first things you’re likely to notice are rocks. Vegetation is sparse, and the soil is thin, so there’s not much to hide the geology here. Particularly stunning views are found where rivers have carved deep canyons through the rock layers.

By the standards of the American West, the rocks forming the Colorado Plateau have had it pretty easy. Although faults have cracked and uplifted rocks, and volcanoes have spewed lava across the plateau, it’s nothing like the surrounding Rocky Mountains or Basin and Range provinces, both of which are the result of eons of violent geology. Mostly, sediments piled up, younger layers on top of older, then eroded, lifted up, and eroded some more.

Water made this desert what it is today. Back before the continents broke apart and began drifting to their present-day locations, Utah was near the equator, just east of a warm ocean. Ancient seas washed over the land, depositing sand, silt, and mud. Layer upon layer, the soils piled up and over time were compressed into sandstones, limestones, and shales.

The ancestral Rocky Mountains rose to the east of the ocean, and just to their west, a trough-like basin formed and was intermittently flushed with seawater. Evaporation caused salts and other minerals to collect on the basin floor; when the climate became wetter, more water rushed in.

As the ancestral Rockies eroded, their bulk washed down into the basin. The sea level rose, washing in more mud and sand. When the seas receded, dry winds blew sand across the region, creating enormous dunes.

Over time, the North American continent drifted north, away from the equator, but this region remained near the sea and was regularly washed by tides, leaving more sand and silt. Just inland, freshwater lakes filled, then dried, and the lakebeds consolidated into shales. During wet periods, streams coursed across the area, carrying and then dropping their loads of mud, silt, and sand.

As the ancestral Rockies wore down to mere hills, other mountains rose, then eroded, contributing their sediments. A turn toward dry weather meant more dry winds, kicking up the sand and building it into massive dunes.

Then, about 15 million years ago, the sea-level plateau began to lift, slowly, steadily, and, by geologic standards, incredibly gently. Some areas were hoisted as high as 10,000 feet above sea level.

As the Colorado Plateau rose, its big rivers carved deep gorges through the uplifting rocks. Today, the Green, Colorado, and San Juan Rivers are responsible for much of the dramatic scenery in southeastern Utah.

More subtle forms of erosion have also contributed to the plateau’s present-day form. Water percolating down through the rock layers is one of the main erosive forces, washing away loose material and dissolving ancient salts, often leaving odd formations such as thin fins of resistant rock.

The many layers of sedimentary rocks forming the Colorado Plateau are all composed of different minerals and have varying densities, so it’s not surprising that erosion affects each layer a bit differently. For instance, sandstones and limestones erode more readily than the harder mudstones or shales.

Erosion isn’t limited to the force of water against rock. Rocks may be worn down or eaten away by a variety of forces, including wind, freezing and thawing, exfoliation (when sheets of rock peel off), oxidation, hydration and carbonation (chemical weathering), plant roots or animal burrows, and dissolving of soft rocks. The ever-deepening channel of the Colorado River through Canyonlands National Park, and the slow thinning of pedestals supporting Arches National Park’s balanced rocks, are all clues that erosion continues unabated. In fact, the Colorado Plateau is still rising, forcing the various erosional forces to just keep taking bigger bites out of the landscape.

The main thing for southeastern Utah travelers to remember is that they’re in the desert.

The high-desert country of the Colorado Plateau is mostly between 3,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation. Annual precipitation ranges from an extremely dry 3 inches in some areas to about 10 inches in others. Mountainous regions—the Abajos and La Sals—are between 10,000 and 13,000 feet and receive abundant rainfall in summer and heavy snows in winter.

Sunny skies prevail through all four seasons. Spring comes early to the canyon country, with weather that’s often windy and rapidly changing. Summer can make its presence known in April, although the real desert heat doesn’t set in until late May or early June. Temperatures then soar into the 90s and 100s at midday, although the dry air makes the heat more bearable. Early morning is the best time for travel in summer. A canyon seep surrounded by hanging gardens or a mountain meadow filled with wildflowers provides a refreshing contrast to the parched desert; other ways to beat the heat include hiking in the mountains and river rafting.

Summer thunderstorm season begins anywhere mid-June-August; huge billowing thunderstorm clouds bring refreshing rains and coolness. During this season, canyon hikers should be alert for flash flooding.

Autumn begins after the rains cease, usually in October, and lasts into November or even December; days are bright and sunny with ideal temperatures, but nights become cold. In both parks, evenings will be cool even in midsummer. Although the day may be baking hot, you’ll need a jacket and a warm sleeping bag for the night.

Winter lasts only about two months at the lower elevations. Light snows on the canyon walls add new beauty to the rock layers. Nighttime temperatures commonly dip into the teens, which is too cold for most campers. Otherwise, winter can be a fine time for travel. Heavy snows rarely occur below 8,000 feet.

Rainwater runs quickly off the rocky desert surfaces and into gullies and canyons. A summer thunderstorm or a rapid late-winter snowmelt can send torrents of mud and boulders rumbling down dry washes and canyons. Backcountry drivers, horseback riders, and hikers need to avoid hazardous locations when storms threaten or unseasonably warm winds blow on the winter snowpack.

Flash floods can sweep away anything in their path, including boulders, cars, and campsites. Do not camp or park in potential flash flood areas. If you come to a section of flooded roadway—a common occurrence on desert roads after storms—wait until the water goes down before crossing (it shouldn’t take long). Summer lightning causes forest and brush fires, posing a danger to hikers who are foolish enough to climb mountains when storms threaten.

The bare rock and loose soils so common in the canyon country do little to hold back the flow of rain or meltwater. In fact, slickrock is effective at shedding water as fast as it comes in contact. Logs and other debris wedged high on canyon walls give proof enough of past floods.

Within the physiographic province of the Colorado Plateau, several different life zones are represented.

In the low desert, shrubs eke out a meager existence. Climbing higher, you’ll pass through grassy steppe, sage, and piñon-juniper woodlands to ponderosa pine. Of all these zones, the piñon-juniper is most common.

But it’s not a lockstep progression of plant A at elevation X and plant B at elevation Z. Soils are an important consideration, with sandstones being more hospitable than shales. Plants will grow wherever the conditions will support them, and southeastern Utah’s parks and public lands have many microenvironments that can lead to surprising plant discoveries. Look for different plants in these different habitats: slickrock (where cracks can gather enough soil to host a few plants), riparian (moist areas with the greatest diversity of life), and terraces and open space (the area between riverbank and slickrock, where shrubs dominate).

Most of the plants you’ll see in southeastern Utah are well adapted to desert life. Many are succulents, which have their own water storage systems in their fleshy stems or leaves. Cacti are the most obvious succulents; they swell with stored moisture during the spring, then slowly shrink and wrinkle as the stored moisture is used.

Other plants have different strategies for making the most of scarce water. Some, such as yucca, have deep roots, taking advantage of what moisture exists in the soil. The leaves of desert plants are often vertical, exposing less surface area to the sun. Leaves may also have very small pores, slowing transpiration, or stems coated with a resinous substance, which also slows water loss. Hairy or light-colored leaves help reflect sunlight.

Desert wildflowers are annuals; they bloom in the spring, when water is available, then form seeds, which can survive the dry hot summer, and die. A particularly wet spring means a bumper crop of wildflowers.

Even though mosses aren’t usually thought of as desert plants, they are found growing in seeps along canyon walls and in cryptobiotic soils. When water is unavailable, mosses dry up; when the water returns, the moss quickly plumps up again.

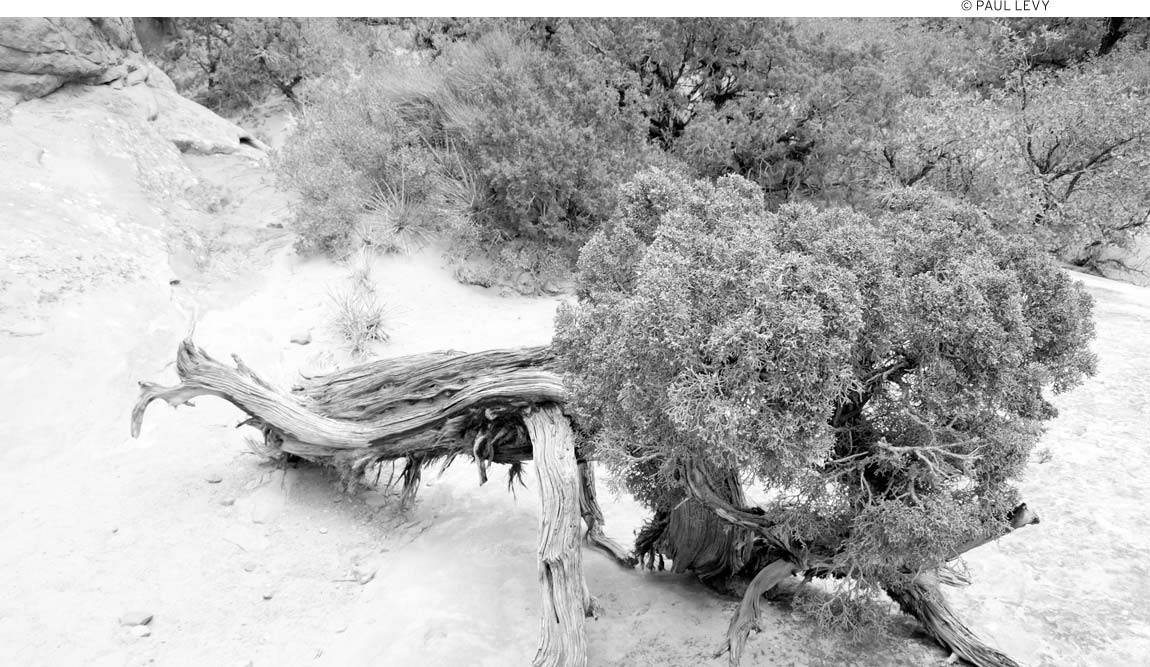

Junipers have a fairly drastic way of dealing with water shortage. During a prolonged dry spell, a juniper tree can shut off the flow of water to one or more of its branches, sacrificing these branches to keep the tree alive.

Watch for clumps of ferns and mosses lit with maidenhair ferns, shooting stars, monkey flowers, columbine, orchids, and bluebells along canyon walls. These unexpectedly lush pockets are called “hanging gardens,” gemlike islands of plantlife nestled into desert cliffs.

Hanging gardens take advantage of a unique microclimate created by the meeting of two rock layers: Navajo sandstone and Kayenta shale. Water percolates down through porous sandstone and, when it hits the denser shale layer, travels laterally along the top of the harder rock and emerges at cliff’s edge. These little springs support lush plantlife.

One of the Colorado Plateau’s most common small trees, the nonnative tamarisk is also one of the peskiest. Imported from the Mediterranean and widely planted along the Colorado River to control erosion, the tamarisk has spread wildly, and its dense stands have crowded out native trees such as cottonwoods. Tamarisks are notoriously thirsty trees, sucking up vast amounts of water, but they give back little in the way of food or habitat for local wildlife. Their thick growth also increases the risk of fire. The National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management are taking steps to control tamarisk; one big project is at the Sand Flats campground near Bluff.

Over much of the Colorado Plateau, the soil is alive. What looks like a grayish-brown crust is actually a dense network of filament-forming blue-green algae intertwined with soil particles, lichens, moss, green algae, and microfungi. This slightly sticky, crusty mass holds the soil together, slowing erosion. Its sponge-like consistency allows it to soak up water and hold it. Plants growing in cryptobiotic soil have a great advantage over plants rooted in dry, sandy soil.

Crytobiotic soils are extremely fragile. Make every effort to avoid stepping on them—stick to trails, slickrock, or rocks instead.

Although they’re not thought of as great “wildlife parks” like Yellowstone or Denali, southeastern Utah’s national parks are home to plenty of animals. However, desert animals are often nocturnal and go unseen by park visitors.

Rodents include squirrels, packrats, kangaroo rats, chipmunks, and porcupines, most of which spend their days in burrows.

One of the few desert rodents out foraging during the day is the white-tailed antelope squirrel, which looks much like a chipmunk. Its white tail reflects the sunlight, and when it needs to cool down a bit, an antelope squirrel smears its face with saliva (yes, that probably would work for you too, but that’s why you have sweat glands). The antelope squirrel lives at lower elevations; higher up you’ll see golden-mantled ground squirrels.

Look for rabbits—desert cottontails and jackrabbits—at dawn and dusk. If you’re rafting the Green or Colorado River, keep an eye out for beavers.

Kangaroo rats are particularly well adapted to desert life. They spend their days in cool burrows, eat only plants, and never drink water: Instead, a kangaroo rat metabolizes dry food in a way that produces water.

Prairie dogs live together in social groups called colonies or towns, which are laced with burrows, featuring a network of entrances for quick pops in and out of the ground. Prairie dogs are preyed on by badgers, coyotes, hawks, and snakes, so a colony will post lookouts who are constantly searching for danger. When threatened, the lookouts “bark” to warn the colony. Utah prairie dogs hibernate during the winter and emerge from their burrows to mate furiously in early April.

As night falls in canyon country, bats emerge from the nooks and crannies that protect them from the day’s heat and begin to feed on mosquitoes and other insects. The tiny gray western pipistrelle is common. It flies early in the evening, feeding near streams, and can be spotted by its somewhat erratic flight. The pallid creature spends a lot of its time creeping across the ground in search of food, and it is a late-night bat. Another common bat, here and across the United States, is the prosaically named big brown bat.

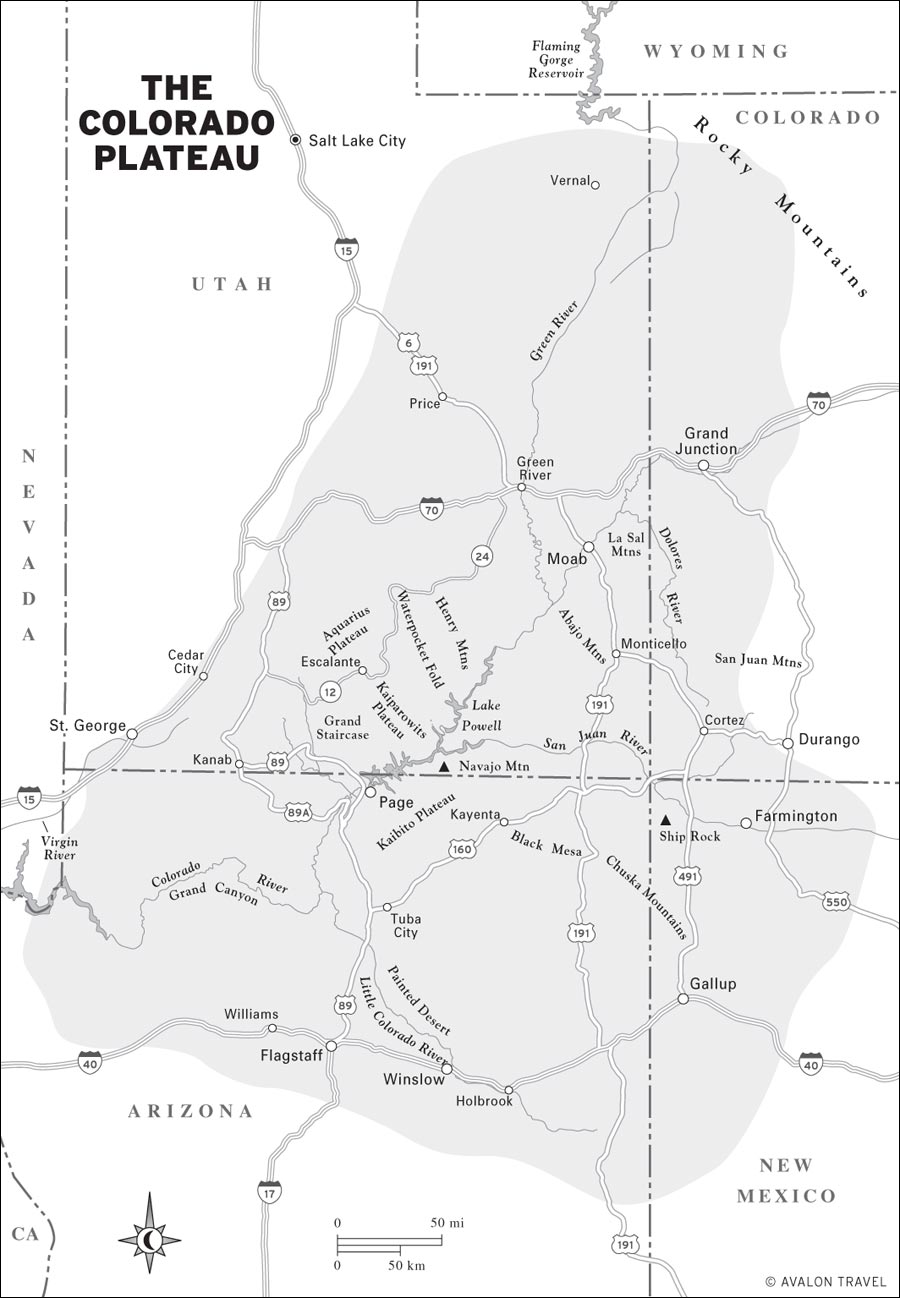

rattlesnake warming against a rock

Mule deer are common across the region, as are coyotes. Other large mammals include the predators: mountain lions and coyotes. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a glimpse of a bobcat or a fox.

If you’re hiking high-elevation trails early in the morning and see something that looks like a small dog in a tree, it’s probably a gray fox. These small (5-10 pounds) foxes live in forested areas and have the catlike ability to climb trees. Kit foxes, which are even tinier than gray foxes, with prominent ears and a big bushy tail, are common in Arches and Canyonlands. Red foxes also live across the plateau.

Desert bighorn sheep live in Arches and Canyonlands, and in other cliff-dominated terrains; look for them trotting across steep rocky ledges. In Arches, they’re frequently sighted along U.S. 191 south of the visitors center. They also roam the talus slopes and side canyons near the Colorado River.

Reptiles are well-suited to desert life. As cold-blooded, or ectothermic, animals, their body temperature depends on the environment rather than on internal metabolism, and it’s easy for them to keep warm in the desert heat. When it’s cold, reptiles hibernate or drastically slow their metabolism.

The western whiptail lizard is common in Arches. You’ll recognize it because its tail is twice as long as its body. Also notable is the western collared lizard, with a bright green body set off by a black collar.

Less flashy but particularly fascinating are the several species of parthenogenetic lizards. All of these lizards are female, and they reproduce by laying eggs that are clones of themselves. Best known is the plateau striped whiptail, but 6 of the 12 species of whiptail present in the area are all-female.

The northern plateau lizard is common at altitudes of about 3,000-6,000 feet. It’s not choosy about its habitat—juniper-piñon woodlands, prairies, riparian woodlands, and rocky hillsides are all perfectly acceptable. This is the lizard you’ll most often see scurrying across your campsite.

Rattlesnakes are present across the area, but given a chance, they’ll get out of your way rather than strike. (Still, they are another good reason to wear sturdy boots.) The midget faded rattlesnake, a small subspecies of the western rattlesnake, lives in burrows and rock crevices and is mostly active at night. Although this snake has especially toxic venom, full venom injections occur in only one-third of all bites.

Although they’re not usually thought of as desert animals, a variety of frogs and toads live on the Colorado Plateau. Tadpoles live in wet springtime potholes as well as in streams and seeps. If you’re camping in a canyon, you may be lucky enough to be serenaded by a toad chorus.

Bullfrogs are not native to the western United States, but since they were introduced in the early 1900s, they have flourished at the expense of native frogs and toads, whose eggs and tadpoles they eat.

The big round toes of the small spotted canyon tree frog make it easy to identify—that is, if you can see this well-camouflaged frog in the first place. These frogs are most active at night, spending their days on streamside rocks or trees.

Toads present in Utah’s parks include the Great Basin spadefoot, red spotted toad, and western woodhouse toad.

Have you ever seen a bird pant? Believe it or not, that’s how desert birds expel heat from their bodies. They allow heat to escape by drooping their wings away from their bodies, exposing thinly feathered areas (sort of like pulling up your shirt and using it to fan your torso).

The various habitats across the Colorado Plateau, such as piñon-juniper, perennial streams, dry washes, and rock cliffs, allow many species of bird to find homes. Birders will find the greatest variety of birds near rivers and streams. Other birds, such as golden eagles, kestrels (small falcons), and peregrine falcons nest high on cliffs and patrol open areas for prey. Common hawks include the red-tailed hawk and northern harrier; late-evening strollers may see great horned owls.

People usually detect the canyon wren by its lovely song; this small long-beaked bird nests in cavities along cliff faces. The related rock wren is—as its name implies—a rock collector: It paves a trail to its nest with pebbles, and the nest itself is lined with rocks. Another canyon bird, the white-throated swift, swoops and calls as it chases insects and mates, rather dramatically, in flight. Swifts are often seen near violet-green swallows (which are equally gymnastic fliers) in Canyonlands and Arches.

Several species of hummingbird (mostly black-chinned, but also broad-tailed and rufous) are often seen in the summer. Woodpeckers are also common, including the northern flicker and red-naped sapsucker, and flycatchers like Say’s phoebe, western kingbird, and western wood pewee can be spotted too. Two warblers—the yellow and the yellow-rumped—are common in the summer, and Wilson’s warbler stops in during spring and fall migrations. Horned larks are present year-round.

Mountain bluebirds are colorful, easy for a novice to identify, and common in Canyonlands and Arches.

Both the well-known scrub jay and its local cousin, the piñon jay, are noisy visitors to almost every picnic. Other icons of western avian life—the turkey vulture, the raven, and the magpie—are widespread and easily spotted.

Obviously, deserts aren’t particularly known for their aquatic life, and the big rivers of the Colorado Plateau are now dominated by nonnative species such as channel catfish and carp. Many of these fish were introduced as game fish. Native fish, like the six-foot, 100-pound Colorado pikeminnow, are now uncommon.

Tarantulas, black widow spiders, and scorpions all live across the Colorado Plateau, and all are objects of many a visitor’s phobias. Although the black widow spider’s venom is toxic, tarantulas deliver only a mildly toxic bite (and they rarely bite humans), and a scorpion’s sting is about like that of a bee.

Utah’s national parks have generally been shielded from the environmental issues that play out in the rest of the state, which has always been business-oriented, with a heavy emphasis on extractive industries such as mining and logging.

The main environmental threats to the parks are consequences of becoming too popular. During the summer, auto and RV traffic can clog park roads, with particularly bad snarls at viewpoint parking areas.

Hikers also have an impact, especially when they tread on fragile cryptobiotic soil. Killing this living soil crust drastically increases erosion in an already easily eroded environment.

Off-road vehicles, or ATVs (all-terrain vehicles), have gone from being the hobby of a small group of off-road enthusiasts to being one of the fastest-growing recreational markets in the country. Although use of ATVs is prohibited in the national parks, these dune buggies on steroids are having a huge impact on public lands adjacent to the parks and on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands that are currently under study for designation as wilderness. The scope of the issue is easy to measure. In 1979 there were 9,000 ATVs registered in Utah. In 2010 there were over 120,000. In addition, the power and dexterity of the machines has greatly increased. Now essentially military-style assault machines that can climb near-vertical cliffs and clamber over any kind of terrain, ATVs are the new “extreme sports” toy of choice, and towns like Moab are now seeing more visitors coming to tear up the backcountry on ATVs than to mountain bike. The problem is that ATVs are extremely destructive to the delicate natural environment of the Colorado Plateau deserts and canyon lands, and the more powerful, roaring, exhaust-belching machines put even the most remote and isolated areas within reach of large numbers of potentially destructive revelers.

Between the two camps—one that would preserve the public land and protect the ancient human artifacts found in remote canyons, the other that sees public land as a playground to be zipped over at high speed—is the BLM. The Moab BLM office has seemed to favor the ATV set, abdicating its role to protect the land and environment for all. Groups like Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA, www.suwa.org) are constantly strategizing to force the BLM to comply with its responsibility for environmental stewardship of public land.

Nonnative species don’t respect park boundaries, and several nonnative animals and plants have established strongholds in Utah’s national parks, altering the local ecology by outcompeting native plants and animals.

Particularly invasive plants include tamarisk (salt cedar), cheatgrass, Russian knapweed, and Russian olive. Tamarisk is often seen as the most troublesome invader. This thirsty Mediterranean plant was imported in the 1800s as an ornamental shrub and was later planted by the Department of Agriculture to slow erosion along the banks of the Colorado River in Arizona. It rapidly took hold, spreading upriver at roughly 12 miles per year, and is now firmly established on all of the Colorado’s tributaries, where it grows in dense stands. Tamarisk consumes a great deal of water and rarely provides food and shelter necessary for the survival of wildlife. It also outcompetes cottonwoods because tamarisk shade inhibits the growth of cottonwood seedlings.

Courthouse Wash in Arches National Park is one of several sites where the National Park Service has made an effort to control tamarisk. Similar control experiments have been established in nearby areas, mostly in small tributary canyons of the Colorado River.

The landscape isn’t the only vivid aspect of southeastern Utah. The area’s human history is also noteworthy. This part of the West has been inhabited for over 10,000 years, and there are remnants of ancient villages and panels of mysterious rock art in now remote canyons. More recently, colonization by Mormon settlers and the establishment of the national parks have brought human history back to this dramatic corner of the Colorado Plateau.

Beginning about 15,000 years ago, nomadic groups of Paleo-Indians traveled across the Colorado Plateau in search of game animals and wild plants, but they left few traces.

Nomadic bands of hunter-gatherers roamed the Colorado Plateau for at least 5,000 years. The climate was probably cooler and wetter when these first people arrived, with both food plants and game animals more abundant than today.

Agriculture was introduced from the south about 2,000 years ago, and it brought about a slow transition to a settled village life. The Fremont culture emerged in the northern part of the region and the Anasazi in the southern part. In some areas, including Arches, both groups lived contemporaneously. Although both groups made pots, baskets, bowls, and jewelry, only the Anasazi constructed masonry villages. Thousands of stone dwellings, ceremonial kivas, and towers built by the Anasazi still stand. Both groups left behind intriguing rock art, either pecked in (petroglyphs) or painted (pictographs).

The Anasazi and Fremont departed from this region about 800 years ago, perhaps because of drought, warfare, or disease. Some of the Anasazi moved south and joined the Pueblo people of present-day Arizona and New Mexico. The fate of the Fremont people remains a mystery.

After the mid-1200s and until white settlers arrived in the late 1800s, small bands of nomadic Ute and Paiute moved through southern Utah. The Navajo began to enter Utah in the early 1800s. None of the three groups established firm control of the region north of the San Juan River, where the present-day national parks are located.

The Old Spanish Trail, used 1829-1848, ran through Utah to connect New Mexico with California, crossing the Colorado River near present-day Moab. Fur trappers and mountain men, including Jedediah Smith, also traveled southern Utah’s canyons in search of beaver and other animals during the early 1800s; inscriptions carved into the sandstone record their passage. In 1859 the U.S. Army’s Macomb Expedition made the first documented description of what is now Canyonlands National Park. Major John Wesley Powell’s pioneering river expeditions down the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869 and 1871-1872 filled in many blank areas on the maps.

In 1849-1850, Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City took the first steps toward colonizing southern Utah. In 1855 a successful experiment in growing cotton along Santa Clara Creek near present-day St. George aroused considerable interest among the Mormons, and the same year, the Elk Ridge Mission was founded near present-day Moab. It lasted only a few months before skirmishes with the Utes led to the deaths of three Mormon settlers and sent the rest fleeing for their lives. Church members had better success when they returned to the area in 1877.

For sheer effort and endurance, the efforts of the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition of 1879-1880 are remarkable. Sixty families with 83 wagons and more than 1,000 head of livestock crossed some of the West’s most rugged canyon country in an attempt to settle at Montezuma Creek on the San Juan River. They almost didn’t make it: A journey expected to take six weeks turned into a six-month ordeal. The exhausted company arrived on the banks of the San Juan River on April 5, 1880. Too tired to continue just 20 easy miles to Montezuma Creek, they stayed and founded the town of Bluff. The Mormons also established other towns in southeastern Utah, relying on ranching, farming, and mining for their livelihoods. None of the communities in the region ever reached a large size; Moab is the biggest, with a current population of 5,500.

In the early 1900s, people other than Native Americans, Mormon settlers, and government explorers began to notice that southern Utah was a remarkably scenic place and that it might be developed for tourism.

In 1909 a presidential Executive Order designated Mukuntuweap (now Zion) National Monument in Zion Canyon. Early homesteaders around Bryce took visiting friends and relatives to see the incredible rock formations, and pretty soon they found themselves in the tourism business. In 1923, when Bryce Canyon National Monument was dedicated, the Union Pacific Railroad took over the fledgling tourist camp and began building Bryce Lodge, and Bryce became a national park in 1928.

Like Bryce and Zion, Arches was also helped along by railroad executives looking to develop their own businesses. In 1929 President Herbert Hoover signed the legislation creating Arches National Monument.

During the 1960s the National Park Service responded to a huge increase in park visitation nationwide by expanding facilities, spurring Congress to change the status of several national monuments to national parks. Canyonlands became a national park in the 1960s, after a spate of uranium prospecting in the nuclear-giddy 1950s. Arches gained national park status in 1971.

One of the oddest statistics about Utah is that it’s the most urban of the country’s western states. Eighty-five percent of the state’s population of 2.8 million live in urban areas, and a full 80 percent reside in the Wasatch Front area. That means that there aren’t many people in remote southeastern Utah. With the exception of Moab, there are no sizable communities in this part of the state. Even the undaunted Mormon settlers found this a forbidding place to settle during their 19th-century agrarian colonization of Utah.

Moab is known as a youthful and dynamic town, and its mountain bikers set the civic tone more than the Mormon Church. However, outside Moab, most small ranching communities in southeastern Utah are still deeply Mormon. It’s a good idea to develop an understanding of Utah’s predominant religion if you plan on spending any time here outside the parks and Moab.

One of the first things to know is that the term Mormon is rarely used by church members themselves. The church’s proper title is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and members prefer to be called Latter-day Saints, Saints (usually this term is just used among church members), or LDS. While calling someone a Mormon isn’t wrong, it’s not quite as respectful.

The religion is based in part on the Book of Mormon, the name given to a text derived from a set of golden plates found by Joseph Smith in 1827 in western New York State. Smith claimed to have been led by an angel to the plates, which were covered with a text written in “reformed Egyptian.” A farmer by upbringing, Smith translated the plates and published an English-language version of the Book of Mormon in 1830.

The Book of Mormon tells the story of the lost tribes of Israel, which, according to Mormon teachings, migrated to North America and became the ancestors of today’s Native Americans. According to the Book of Mormon, Jesus also journeyed to North America, and the book includes teachings and prophecies that Christ supposedly gave to the ancient Native Americans.

The most stirring and unifying aspect of Mormon history is the incredible westward migration made by the small, fiercely dedicated band of Mormon pioneers in the 1840s. Smith and his followers were persecuted in New York and then in their newly founded utopian communities in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. After Smith was murdered near Carthage, Illinois, in 1844, the group decided to press even farther westward toward the frontier, led by church president Brigham Young. The journey across the then very Wild West to the Great Salt Lake basin was made by horse, wagon, or handcart—hundreds of Mormon pioneers pulled their belongings across the Great Plains in small carts. The first group of Mormon pioneers reached what is now the Salt Lake City area in 1847. The bravery and tenacity of the group’s two-year migration forms the basis of many Utah residents’ fierce pride in their state and their religion.

Most people know that LDS members are clean-living, family-focused people who eschew alcohol, tobacco, and stimulants, including caffeine. This can make it a little tough for visitors to feed their own vices, and indeed, it may make what formerly seemed like a normal habit feel a little more sinister. But Utah has loosened up a lot in the last decade or so, largely thanks to having hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics, and it’s really not too hard to find a place to have a beer with dinner, although you may have to make a special request. Towns near the national parks are particularly used to hosting non-Mormons, and residents attach virtually no stigma to waking up with a cup of coffee or winding down with a glass of wine.

It’s an oddity of history that most visitors to Utah’s national parks will see much more evidence of the state’s ancient native residents—in the form of eerie rock art, stone pueblos, and storehouses—than they will of today’s remaining Native Americans. The prehistoric residents of the canyons of southeastern Utah left their mark on the land but largely moved on. The fate of the ancient Fremont people has been lost to history, and the abandonment of Anasazi, or Ancestral Puebloan, villages is a mystery still being unearthed by archaeologists. When the Mormons arrived in the 1840s, isolated bands of Native Americans lived in the river canyons. Federal reservations were granted to several of these groups.

Several bands of Utes, or Núuci, ranged over large areas of central and eastern Utah and adjacent Colorado. Originally hunter-gatherers, they acquired horses around 1800 and became skilled raiders. Customs adopted from Plains people included the use of rawhide, tepees, and the travois, a sled used to carry goods. The discovery of gold in southern Colorado and the pressures of farmers there and in Utah forced the Utes to move and renegotiate treaties many times. They now have the large Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in northeast Utah, the small White Mesa Indian Reservation in southeast Utah, and the Ute Mountain Indian Reservation in southwest Colorado and northwest New Mexico.

Calling themselves Diné, the Navajo moved into the San Juan River area around 1600. The Navajo have proved exceptionally adaptable in learning new skills from other cultures: Many Navajo crafts, clothing, and religious practices have come from Native American, Spanish, and Anglo neighbors. The Navajo were the first in the area to move away from hunting and gathering lifestyles, relying instead on the farming and shepherding techniques they had learned from the Spanish. The Navajo are one of the largest Native American groups in the country, with 16 million acres of exceptionally scenic land in southeast Utah and adjacent Arizona and New Mexico. The Navajo Nation’s headquarters is at Window Rock, Arizona.