10

Freedom and Determinism

It is a datum of human experience that our actions seem to be free. For most, this is good reason to think that we are in fact free. Moreover, we tend to think this to be a good thing. We think it a good thing to be self-determiners of our actions, our character, and the story of our lives. This freedom grounds our moral ascriptions of praise and blame with respect to the actions, character, and life story of others and ourselves. “Free will” is what we call this ability or power to choose our actions, character, and life story.1 But there is a problem lurking below the surface with respect to free will. Consider the following dilemma:

- If determinism is true, free will is an illusion.

- If determinism is not true, free will is arbitrary.

Determinism—roughly, the idea that the future is fixed—is either true or not. Either way, free will seems to be impossible. The tension between claims 1 and 2 highlights what is often called the problem of free will. In this chapter we shall explore the problem of free will. We will be particularly interested in whether there are strategies that can be plausibly employed in order to avoid one or both horns of the dilemma highlighted by claims 1 and 2. We begin by considering determinism.

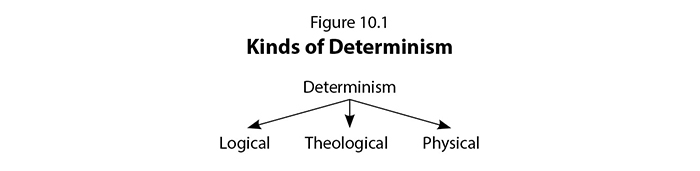

There are basically three versions of determinism: logical, theological, and physical (see fig. 10.1). In all versions of determinism, the future is fixed by some determining factor. With logical determinism, the determining factor is the fact that propositions about the future are already true or false. Consider the act of reading Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone on your twelfth birthday. One hundred years prior to your twelfth birthday, the proposition P, “You will read Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone on your twelfth birthday,” was either true or false. Assume that the proposition P was true. If P was true, then necessarily, on your twelfth birthday, you would read Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. But if you had no choice regarding the truth of P one hundred years ago (and how could you?), then you have no choice about reading Harry Potter on your birthday either. By the time of your twelfth birthday, it was too late: you couldn’t prevent P from being true a hundred years earlier, and it is also too late to prevent what necessarily follows from the truth of P (namely, your reading the book on your twelfth birthday). While many remain unmoved by the threat of logical determinism, the task of deciding what exactly is wrong with the above line of reasoning has proved difficult, quickly moving into areas of fundamental metaphysics regarding the nature of truth, time, dependence, and explanation.2

Theological determinism moves not from prior truths about what you do but from either prior divine decrees or divine beliefs about what you do.3 An example of theological determinism grounded in the decrees of God is Calvinism, which endorses the claim that God is the sufficient cause of everything that happens in the world, including the good and evil actions of humans.4 In a later section we will consider an example of theological determinism grounded in divine beliefs about future contingent acts of humans. For the remainder of this section, we’ll consider physical determinism.

Consider the event of my hand raising at time t1. According to physical determinism, the event of my hand raising at t1 is a consequence of the past history of the universe (prior to time t1) and the laws of nature. The past history of the universe and the laws of nature are the determining factors of the event of my hand raising. In other words, given the past and the laws of nature, I could not have done otherwise than raise my hand at time t1. At any time before t1, the future was fixed for me: it was determined that I would raise my hand at time t1. If my choices and actions are inevitable, given the past and the laws of nature, then I am not free. Thus the argument goes: if determinism is true, free will is an illusion (i.e., claim 1 of our dilemma is true).

At this point the defender of free will has two options. Such a person can deny the first part of claim 1 and argue that determinism is false or deny the second part of claim 1 and argue that freedom is compatible with determinism. Let’s consider the first part of claim 1. Is physical determinism true? Most philosophers think the answer to this question is an empirical matter, investigated by discovering the nature of the world.5 It certainly seems as if the world operates according to fixed laws of nature. Each day is followed by night, each spring is followed by summer, acorns fall to the ground when released by oak trees, and so on. The world seems to be a grand machine operating according to the exceptionless laws of classical (Newtonian) physics. Indeed, many philosophers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries thought classical science entailed physical determinism.6 However, this picture of the world is no longer taken for granted due to the advent of contemporary quantum mechanics and the possibility of probabilistic laws of nature.

If the world of elementary particles (the microworld governed by quantum mechanics) is in fact indeterministic, then physical determinism is false. While the issue is by no means settled, there seems to be somewhat of a consensus that the quantum world is indeterministic.7 Let us, for the sake of argument, assume that the quantum world is indeterministic. Does the indeterminancy of the quantum world ground the possibility of genuine freedom? It is not clear that it does. While quantum indeterminancy is relevant to elementary particles and their behavior, it is not obviously relevant to larger-scale physical objects such as the human brain and body (presumably the seat of our deliberations and actions). If somehow indeterministic microevents were “amplified” so that they could produce large-scale effects within the human brain and body, such effects, like their microbase, would also happen by chance.8 These large-scale effects, which result from indeterministic “quantum jumps,” are unpredictable and uncontrollable—more like a sudden twitch of the face or a random thought traversing through the mind than a responsible and hence free action.9 But then we’ve avoided, in this first attempt, the rocky heights of claim 1, only to be shattered on the crags of claim 2. It is time to consider the second option for the defender of free will with respect to claim 1: the idea that freedom is compatible with determinism and therefore not an illusion. We begin by considering the nature of freedom.

Freedom

What are the necessary conditions for genuine freedom? Intuitively, an action or choice is free if it is one of a number of alternative possibilities. So on this way of thinking, for example, I am free with regard to my choice to wear the blue shirt if it is the case that I could also choose the red, black, or green shirt instead. This intuition undergirds claim 1 of our dilemma. If the future is not “open” in any genuine sense, if there is no power to do otherwise, then there is no freedom. Many philosophers think this is the sine qua non—the essential condition—of freedom; without it, an action or choice is simply not free. In addition, many think freedom requires that each agent is ultimately responsible for their own actions and choices. The agent must be the ultimate source or origin of the action or choice and not merely a passive conduit of external causes that are outside the agent’s control (such as the past, the laws of nature, or the decree of God). If alternative possibilities (AP) and ultimate responsibility (UR) are necessary conditions for freedom, it is not difficult to see how determinism poses a threat to the possibility of freedom.

Not all, however, think freedom is incompatible with determinism. Some philosophers argue that there is no conflict between freedom and determinism. This view, known as compatibilism, argues that claim 1 of our dilemma is false. A compatibilist who also thinks that we do have free will is called a soft determinist. In fact, the soft determinist often thinks freedom requires determinism. This is because, as claim 2 states, if determinism is false our actions and choices seem arbitrary, either uncaused, in which case the agent is not ultimately responsible, or caused (by reasons or desires) but not necessitated, in which case the agent acts or chooses irrationally or randomly. All that is required for freedom, says the compatibilist, is the “agent’s unhindered ability to do [or choose] what he wants.”10 As long as the agent does or chooses what this agent wants to do or choose, and does so without coercion, the act or choice is free even if determined.

But what about AP and UR? Does the compatibilist reject our intuitively plausible conditions for genuine freedom? With respect to AP, the compatibilist (ironically!) has options. One can either provide a Conditional Analysis of AP or deny that AP is a necessary condition for freedom. The compatibilist who thinks AP is true can offer a Conditional Analysis of “what I could have done otherwise” that is consistent with being determined. To say “I could have become an accountant instead of a philosopher” is analyzed by the compatibilist as “I would have become an accountant instead of a philosopher, if I had wanted to.” There is a sense, then, says the compatibilist, in which I could have done otherwise, even though my actions and choices are determined. And if the conditional analysis of “could have done otherwise” is acceptable, then it seems the compatibilist can also affirm an important condition of what it means to be free.

Unfortunately, many philosophers think the Conditional Analysis fails. If what I want is determined, then it doesn’t seem, after all, that I really have any alternative possibilities. Recall my act of hand raising at time t1. If at t1 I want to raise my hand and nothing prevents me from doing what I want with respect to my hand raising at t1, then my act is done freely, according to the compatibilist. But at t1 there are no genuine alternative possibilities before me. Given my want, a want over which I have no control, I could act in only one way. What are needed, argues the incompatibilist, are genuine alternative possibilities at the time of the action or choice. But given determinism, there is only one alternative at the time of the action or choice, so the conditional analysis gives the wrong results.11

The second option, to deny that AP is a necessary condition for freedom, seems more promising for the compatibilist. As it turns out, there are powerful reasons provided by compatibilists for thinking the principle of alternative possibilities is false. In 1969, the philosopher Harry Frankfurt published an influential paper that ignited the debate over the truth of AP.12 Frankfurt gives various examples designed to show that someone could be responsible, and hence free, even if there was no ability to do otherwise. If these “Frankfurt-style counterexamples,” as they have come to be called, are successful, then AP is false; alternative possibilities are not required for moral responsibility or freedom. A typical Frankfurt-style counterexample is this: Suppose that Black wants Jones to kill Smith. If Jones kills Smith on his own, then Black will not intervene. If when the moment comes, however, it appears that Jones will not kill Smith (Black is an expert at reading people), then Black, who has secretly planted a chip in Jones’s brain, will press a button, manipulating Jones’s brain so that he will kill Smith. Suppose Jones wants to kill Smith and does so. Black remains in the background, and the chip in Jones’s brain is dormant. Did Jones act responsibly, and hence freely, in killing Smith? It seems that he did. We blame Jones because he killed Smith on his own and wanted to. But he could not have done otherwise. Black was ready to intervene if needed. Therefore, we have a counterexample to the claim that freedom requires AP.

There is considerable debate over whether Frankfurt-style counterexamples are successful. The defender of AP might argue that there are in fact genuine alternative possibilities in these cases. For example, while Jones does not have the alternatives of “kill Smith” or “not kill Smith,” he does have the alternative of “kill Smith on my own” or “kill Smith as a result of Black’s manipulation.”13 The defender of Frankfurt-style counterexamples in turn retorts that this “flicker of freedom . . . is too thin a reed on which to rest moral responsibility.”14 Alternatively, the defender of AP might argue that Frankfurt-style counterexamples presuppose the truth of determinism and thus beg the question against indeterminism.15 If freedom requires indeterminism, then the only way Black can ensure that Jones will kill Smith is to act in advance to bring it about that Jones kills Smith (after all, Black cannot ensure that he reliably predicts Jones’s actions given indeterminism). But if it is necessary that Black actually needs to intervene to ensure that Jones kills Smith, then while it is true that Jones could not have done otherwise, it is also the case that Jones is not responsible. Thus moral responsibility (and freedom) does require AP if indeterminism is true. At this point, there seems to be somewhat of a stalemate between the compatibilist and the incompatibilist. It is not clear whether AP is required for freedom.

What is clear is that if compatibilism is true, we must give up UR as a necessary condition for freedom.16 Given compatibilism, an agent contributes to action—for example, I contribute to the action of raising my hand at time t1 by choosing to do so and moving my body in order to bring about the event of my hand raising—but the agent still is not the ultimate source of action. To be the ultimate source of action, nothing outside the agent guarantees the action. But, given physical determinism, the past and the laws of nature do guarantee the action. Thus the compatibilist requires that we give up on at least one, and maybe both, of the parts of our prephilosophical intuition regarding freedom.17

Incompatibilism

The incompatibilist argues that determinism is incompatible with freedom. That is, claim 1 of our dilemma is true. A powerful argument called the Consequence Argument has been advanced to show the incompatibility of determinism and freedom.18 Informally stated, the argument is as follows: Assume determinism is true. If determinism is true, my act of hand raising at time t1 is the necessary consequence of the past and the laws of nature. There is nothing I can do to change the past and the laws of nature; they are beyond my control. But if my hand raising at t1 is a necessary consequence of the past and the laws of nature, and the past and the laws of nature are beyond my control, then my hand raising at t1 is also beyond my control. Generalized, since all my actions are determined, it follows that all my actions are beyond my control. That is, if determinism is true, there is no freedom.

The key inference of the Consequence Argument is the Principle Beta: “If there is nothing agent S can do about X, and Y is a necessary consequence of X, then there is nothing agent S can do about Y either.” Principle Beta seems intuitively true. The compatibilist, of course, rejects the Consequence Argument and focuses attention on the viability of Principle Beta. One strategy, as we have already seen, is to offer a Conditional Analysis of the word “can” found within Principle Beta and the premises of the Consequence Argument: “You can do action A” means “You would do action A if you wanted to.” But as we have seen, many think the Conditional Analysis fails. This does not mean incompatibilism wins; there are other compatibilist counterexamples to Principle Beta on offer. Still, it is safe to say that the burden of proof is on the compatibilist to provide a viable account of “can” and “could have done otherwise” that either undercuts Principle Beta or refutes other premises of the Consequence Argument.19

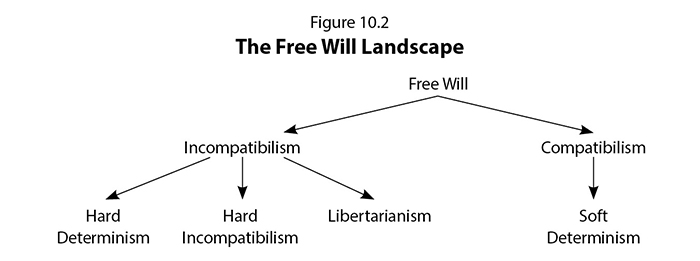

Assume the Consequence Argument is sound, and thus determinism is incompatible with freedom. It does not follow that there is freedom in the world. There are three kinds of incompatibilism: hard determinism, hard incompatibilism, and libertarianism (see fig. 10.2). The hard determinist thinks incompatibilism and determinism are true and denies the reality of genuine freedom. The hard incompatibilist thinks incompatibilism is true and is unsure whether determinism is true or false, but either way denies the reality of genuine freedom. The libertarian (about free will, not politics) thinks incompatibilism is true and affirms genuine freedom. All accept claim 1 of our dilemma. The defender of libertarian freedom rejects claim 2. It is time to consider whether indeterminism is compatible with freedom.

The problem is that the denial of determinism isn’t enough to secure the reality of genuine freedom. J. J. C. Smart succinctly captures the worry. He argues that all events are the result of either deterministic forces (what he calls “unbroken causal continuity”) or chance. But if our actions result from chance, they are not under our control; hence, they are not free actions.20 The idea is that there is no “space” for genuine (libertarian) freedom between something being undetermined and its happening as a matter of chance or luck. What is needed is some “extra factor” to ground libertarian freedom.21 Many defenders of libertarian freedom have responded to this challenge by postulating agents as the needed “extra factor”: agents are the cause of undetermined yet free actions.

Agent Causation

Consider again the act of my hand raising at time t1. Suppose the children next door are playing backyard football, and a wayward pass results in the football hitting my raised hand at time t2. The event of the football hitting my hand at t2 brings about the event of the football coming to rest on the ground at t3. This is an example of event causation. But what about the act of my hand raising at t1? Is this also an example of event causation? Some think another kind of causation is at work in this act of mine, called agent causation. On this view, I am a substance, a continuant that is the “first cause” of my action. As an agent cause, I am a self-determiner of my actions, character, and life story. Thus I am ultimately responsible (UR) and in many cases (if not all cases, depending on the role of character in influencing choices and actions) able to do otherwise (AP). As Roderick Chisholm puts it, “Each of us, when we act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing—or no one—causes us to cause those events to happen.”22

While agency theory is an attractive “extra factor,” a factor that seems to capture the way we experience our own choices and activity, many find the idea at worst incoherent or at best deeply mysterious. A prominent objection to agent causation is that it does not eliminate randomness: if the free actions of agents are undetermined, then given the exact prior circumstances, an agent could have chosen (say) A or B. But then it seems that the actual choice made by the agent is entirely random and arbitrary. Hence, it is argued, agent causation is incoherent. In response, the agent theorist points out that the reasons and purposes of an agent can play a role, as motivating factors, in the agent’s self-determining choices. Reasons and purposes influence the agent’s choices without causing them. I raised my hand at t1 because I wanted to; I was exercising (let’s say) in order to remain healthy. This reason (“I wanted to”) and purpose (“in order to remain healthy”) influenced my decision to raise my hand at t1. If so, then the choices and actions of agents are not random: they are done for reasons.23 Regarding the charge of mystery, while it can be granted that agent causation is to some extent mysterious, it is no more mysterious than the concept of causation itself (which, as Hume and others have taught us, is notoriously difficult to analyze). Moreover, the worry of mystery is mitigated by the fact that we are more familiar with agent causation, via introspection into our own experience, than we are with event causation. It is more basic; our concept of event causation is arguably parasitic on our experience as causal agents. Finally, while agent causation might be difficult to reconcile with naturalism and its preference for event causation, it fits nicely within a broadly theistic view of the world. If God exists and is the first cause of the physical universe, agent causation is one of the most basic facts of reality.24 We conclude: there are good reasons to think that agent causation is the necessary “extra factor” for libertarian freedom.25

In summary, if there is to be genuine (libertarian) freedom, the following four conditions must be met: (1) incompatibilism is true, (2) the agent is ultimately responsible for his or her choices and actions (UR), (3) agent causation is true, and (4) at least sometimes there are alternative possibilities (AP) (see table 10.1).26

Table 10.1. Necessary Conditions for Libertarian Freedom

| Incompatibilism | Freedom is not compatible with being determined. |

| Ultimate Responsibility (UR) | The agent is the ultimate source of the self’s choices and actions. |

| Agent Causation | The agent is the “first cause” of one’s own choices and actions. |

| Alternative Possibilities (AP) | The agent “could have done otherwise” with respect to choices or actions (either at the time of the choice or action or at earlier “will-setting moments”). |

God and Freedom

The debate over the problem of free will intensifies when the existence and nature of God are factored in. Consider the question of whether human freedom is compatible with divine foreknowledge. The problem is this: God, as traditionally conceived, is omniscient. From eternity past, God knows that I will raise my hand at time t1 (i.e., God foreknows the future). God’s past belief about what I will do at t1 is something over which I have no control. Moreover, since God cannot be mistaken in his beliefs, I will necessarily raise my hand at t1. But if I will necessarily raise my hand at t1, then I am not free.

In order to understand prominent responses to the problem of divine foreknowledge and human freedom, consider the following set of jointly inconsistent claims:

3. God has exhaustive foreknowledge of the future.

4. I have no control over God’s past beliefs about the future.

5. Determinism is true.

6. There is libertarian freedom.

In order to render this set consistent, one or more of these claims must be rejected. The compatibilist accepts claims 3–5 and rejects claim 6. Human freedom is compatible with being determined. However, many think theistic compatibilism is unacceptable.27 While it is difficult with all versions of compatibilism to account for human moral responsibility, theistic compatibilism seems to render God as the ultimate cause of all human actions and thereby the author of sin and evil. Moreover, it is not clear, on theistic compatibilism, that God desires all to be saved (contrary to 1 Tim. 2:4). The damned are consigned to hell by virtue of God’s sovereign decree, a decree issued long before they were born. As a result, it is hard to make sense of the claim that God is wholly good. Given the apparent insuperability of these worries, many theists will be attracted to libertarian accounts of freedom.28

The defender of libertarian freedom will, of course, reject claim 5, but in order to do so will also need to reject either claim 3 or claim 4 since, as we have seen, 5 is entailed by 3 and 4. The open theist rejects claim 3: God does not have exhaustive foreknowledge of the future. The future is “open”; God is a “risk taker” who in love willingly exposes himself to the real possibility of failure and disappointment.29 While there are important defenders of open theism, it has not garnered wide acceptance among traditional theists.30 This is partly because open theism seems to undermine the phenomenon of biblical prophecy and calls into question God’s ability to bring his plan for the world to fulfillment.

Others reject claim 4. The Molinist, for example, argues that in addition to foreknowledge, God possesses “middle knowledge”: knowledge of what libertarianly free creatures would do in any particular situation.31 Thus, given Molinism (named after Luis de Molina [1535–1600]), we do have a kind of power over the past; we have counterfactual power over God’s past beliefs. If I were to act differently at time t1 (e.g., and not raise my hand), God’s middle knowledge would have been different, and he would have foreknown that I will not raise my hand at t1. God’s past beliefs track our future choices, but (given Molinism) they do not determine (or cause) our future choices.32 Ockhamism is another view that rejects claim 4. The Ockhamist solution, first put forth by William of Ockham (1285–1347), makes a distinction between hard facts (facts simply about the past) and soft facts (facts not simply about the past since they depend on something that happens in the future). With this distinction in place, the Ockhamist claims that while it is not in our power to affect hard facts about the past, it is in our power to affect soft facts about the past, and God’s past beliefs about what I will do are all soft facts.33 While Molinism or Ockhamism are not without problems, they represent attractive solutions to the problem of divine foreknowledge and human freedom that account for our prephilosophical intuitions about the nature of freedom and moral responsibility, all the while preserving a high view of divine sovereignty, a robust doctrine of divine omniscience, and belief in the goodness of God.

Conclusion

In this chapter we’ve explored “the problem of free will.” The problem is multifaceted, requiring attention to the question of determinism, the nature of moral responsibility, the possibility of agent causation, and the role of character in choice and action. Adding God into the mix further complicates things. While we side with the incompatibilist (and the virtue libertarian), we think there is freedom here to maneuver as a Christian and, as with many areas of philosophical and theological investigation, would encourage you to hold your position as thoughtfully as you can with intellectual humility and theological modesty.

1. Meghan Griffith, Free Will: The Basics (New York: Routledge, 2013), 3.

2. For an excellent overview of the current debate over logical determinism (often called logical fatalism), see the introduction by John Martin Fischer and Patrick Todd to Freedom, Fatalism, and Foreknowledge, ed. Fischer and Todd (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 1–38.

3. Fischer and Todd, Freedom, Fatalism, and Foreknowledge, 22.

4. Robert Kane, A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 148.

5. Kevin Timpe, Free Will in Philosophical Theology (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 8.

6. But for an argument that classical science does not entail physical determinism, see Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), chap. 3.

7. For a helpful discussion of the relevant issues in interpreting quantum mechanics, see Tim Maudlin, “Distilling Metaphysics from Quantum Physics,” in The Oxford Handbook of Metaphysics, ed. Michael J. Loux and Dean W. Zimmerman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 461–87.

8. Robert C. Bishop considers various routes for amplification such as Chaos Theory and Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics, in “Chaos, Indeterminism, and Free Will,” in The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, ed. Robert Kane (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 119–21.

9. Kane, Introduction to Free Will, 9.

10. Griffith, Free Will, 41. This is the view of the “classic compatibilist” of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such as Hobbes and Hume.

11. Griffith, Free Will, 42.

12. Harry Frankfurt, “Alternative Possibilities and Moral Responsibility,” Journal of Philosophy 66 (1969): 829–39. Frankfurt’s principle of alternative possibilities (PAP) focuses on moral responsibility, whereas AP above focuses on freedom. We are treating Frankfurt’s PAP as roughly synonymous with AP, since it is widely held that agents are morally responsible for their own actions or choices only if free.

13. Griffith, Free Will, 45.

14. John Martin Fischer, “Frankfurt-type Examples and Semi-Compatibilism,” in Kane, Oxford Handbook of Free Will, 289. This essay is an excellent overview of the debate about Frankfurt-style counterexamples. Fischer’s own view is that determinism probably does rule out alternative possibilities, but moral responsibility and freedom do not require alternative possibilities. This view is called semicompatibilism. Alternatively, some argue that even if AP (alternative possibilities) is false, determinism does rule out responsibility and freedom since freedom and responsibility require only UR (ultimate responsibility). This incompatibilist view is called source incompatibilism.

15. This objection is called “The Indeterminist World Objection” by Kane. See Kane, Introduction to Free Will, 87–88.

16. For what follows in this paragraph, see Griffith, Free Will, 47.

17. For an overview of more sophisticated new compatibilist theories, see Kane, Introduction to Free Will, chaps. 9 and 10; and Griffith, Free Will, chap. 4.

18. The Consequence Argument has been ably defended by, among others, Peter van Inwagen, An Essay on Free Will (Oxford: Clarendon, 1983); Carl Ginet, On Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); and Timothy O’Connor, “Indeterminism and Free Agency: Three Recent Views,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 53 (1993): 499–526.

19. For a nice overview of contemporary compatibilist responses to the Consequence Argument, see Tomis Kapitan, “A Master Argument for Incompatibilism?,” in Kane, The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, chap. 6. See also Peter van Inwagen, “Free Will Remains a Mystery,” in Kane, The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, chap. 7, for van Inwagen’s discussion of a successful counterexample to one understanding of Principle Beta and his fix. Van Inwagen remains convinced that Principle Beta is valid and the Consequence Argument sound.

20. J. J. C. Smart, “Free Will, Praise and Blame,” in Free Will, ed. Gary Watson, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 63.

21. Kane, Introduction to Free Will, 39.

22. Roderick M. Chisholm, “Human Freedom and the Self,” in Watson, Free Will, 34.

23. For a robust defense of agent causation, including reasons and explanations for actions, see Timothy O’Connor, “Agent Causation,” in Agents, Causes, and Events: Essays on Indeterminism and Free Will, ed. Timothy O’Connor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), chap. 10.

24. For more on the difficulty of squaring agent causation with materialism, see J. A. Cover and John O’Leary-Hawthorne, “Free Agency and Materialism,” in Faith, Freedom, and Rationality, ed. Daniel Howard-Snyder and Jeff Jordan (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996), 47–72. For an argument that libertarian free will is incompatible with naturalism, see Jason Turner, “The Incompatibility of Free Will and Naturalism,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 87, no. 4 (2009): 565–87.

25. For a survey of alternative “extra factor” strategies for the defender of libertarian freedom, see Kane, Introduction to Free Will, chap. 5; and Griffith, Free Will, chap. 5.

26. Virtue Libertarianism, a view consistent with the above conditions for freedom, allows that an agent might not have genuine alternative possibilities at the time of an action. Still, the agent did, at some point in the near or distant past, have alternative possibilities and thus is responsible for the self’s character. Thus if we understand AP broadly as alternative possibilities at the time of a decision or action or some time in the causal past (at key “will-setting moments”), we can preserve the connection between alternative possibilities and responsibility and allow a role for character in our account of libertarian freedom. Virtue Libertarianism is a version of Soft Libertarianism, which is the view that alternative possibilities are not always required for genuine freedom (or not always required at the time of the action or choice). For more on Virtue Libertarianism, see Timpe, Free Will in Philosophical Theology.

27. See, e.g., Jerry L. Walls, “Why No Classical Theist, Let Alone Orthodox Christian, Should Ever Be a Compatibilist,” Philosophia Christi 13, no. 1 (2011): 75–104. In reply, see Steven B. Cowan and Greg A. Welty, “Pharaoh’s Magicians Redivivus: A Response to Jerry Walls on Christian Compatibilism,” Philosophia Christi 17, no. 1 (2015): 151–73. But see Jerry Walls, “Pharaoh’s Magicians Foiled Again: Reply to Cowan and Welty,” Philosophia Christi 17, no. 2 (2015): 411–26, and in response Steven B. Cowan and Greg A. Welty, “Won’t Get Foiled Again: A Rejoinder to Jerry Walls,” Philosophia Christi 17, no. 2 (2015): 427–42.

28. Arguably, the biblical position on human freedom is underdetermined. It may be that Scripture is consistent with both compatibilism and libertarianism (yet see the preceding footnote for Walls’s arguments that Scripture demands libertarianism). For an excellent discussion of how to understand the biblical teaching on the nature of human freedom, see Thomas H. McCall, An Invitation to Analytic Christian Theology (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015), chap. 2.

29. William Hasker, “A Philosophical Perspective,” in The Openness of God: A Biblical Challenge to the Traditional Understanding of God, by Clark Pinnock et al. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1994), 151.

30. In addition to Hasker and other contributors to The Openness of God, important defenders of Open Theism include Richard Swinburne and Peter van Inwagen. For bibliographical information on key philosophical defenders of Open Theism, see the introduction to Fischer and Todd, Freedom, Fatalism, and Foreknowledge, 26–27.

31. For more on Molinism, see the discussion in chapter 14.

32. For more, see William Lane Craig, “Middle Knowledge: A Calvinist-Arminian Rapprochement?,” in The Grace of God and the Will of Man, ed. Clark H. Pinnock (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1989), 141–64.

33. For more, see Alvin Plantinga, “On Ockham’s Way Out,” Faith and Philosophy 3, no. 3 (1986): 235–69.