15

The Possibility of Life after Death

Philosophy of religion deals with all sorts of issues that human beings care about very deeply. It deals with questions about God’s existence and nature, his purposes in the world, and why he allows evil and suffering in the world. In addition to this, philosophy of religion deals with questions about miracles, prayer, and the way God interacts with the world. Moreover, as we will see in this chapter, philosophy of religion deals with the possibility of life after death.

Christians all over the world and throughout history have rejected the idea that death is the final and conclusive result of our existence. Christians have instead affirmed the reality of heaven and the idea that believers live forever in God’s presence and enjoy eternal bliss. Christians have not been the only ones to affirm ideas like this. Throughout the world and the various religions that people practice, the possibility of an afterlife is a widely held idea. In short, human beings generally believe that life goes on even after we die.

Despite how widespread these ideas are, however, they are not without difficulty and questions. Is it really possible to live after we die? If so, how does that work, and what should we expect it to be like? This chapter explores these kinds of questions, but it does so from within a Christian point of view. We shall first set forth what is entailed within a Christian understanding of life after death and will then explore the kinds of problems that must be addressed. After that, we will explore the rationales we have for belief in the existence of the soul and the possibility of bodily resurrection.

A Christian View of Life after Death

Throughout history, Christians have typically been the most vocal and insistent that we survive our deaths and continue to experience life. At the same time, Christians, at least in recent history, can also be guilty of offering nothing more than a very general and simplistic account of this life after death. If asked what happens to people when they die, they might simply respond with something like, “They go to heaven.” But, of course, Christianity has more to say about this matter, and as we delve into the above questions, it is important to make sure we have a grasp of some of its primary teachings on the subject. Christianity does affirm that there is a heaven and a hell, and that people will go to one or the other. When Christianity speaks about the afterlife, there are two general kinds of ideas that seem to drive much of the discussion.

First, Christianity seems to affirm that human beings have souls that survive the death of the body. At death, the soul departs and goes to a spiritual realm of reward or punishment. The spiritual realm of reward has been referred to as the intermediate state in the presence of Christ, where the soul awaits the resurrection of the body. Thomas Aquinas describes this view in rather blunt fashion: “Since a place is assigned to souls in keeping with their reward or punishment, as soon as the soul is set free from the body it is either plunged into hell or soars to heaven.”1 Operating within a different theological tradition, John Calvin offers a similar summary of Christian thought on this point. Noting numerous allusions to it in Scripture, he says,

The apostle banishes doubt when he teaches that we have been gathered “to the spirits of just men” [Heb. 12:23 NKJV]. By these words he means that we are in fellowship with the holy patriarchs who, although dead, cultivate the same godliness as we, so that we cannot be members of Christ unless we unite ourselves with them. And if souls when divested of their bodies did not still retain their essence, and have capacity of blessed glory, Christ would not have said to the thief: “Today you will be with me in paradise” [Luke 23:43 NKJV]. Relying on such clear testimonies, in dying let us not hesitate, after Christ’s example, to entrust our souls to God [Luke 23:46], or, after Stephen’s example, to commit them into Christ’s keeping [Acts 7:59], who is called with good reason their faithful “Shepherd and Bishop” [1 Pet. 2:25 KJV].2

What Calvin affirms here is the existence of the intermediate state. He is less willing, however, to say much about the nature of this state. He adds, “Scripture goes no farther than to say that Christ is present with them, and receives them into paradise [cf. John 12:32] that they may obtain consolation, while the souls of the reprobate suffer such torments as they deserve.”3 Passages like these from Aquinas and Calvin suggest a wide-ranging affirmation of the doctrine from within the Catholic and Protestant traditions. Yet this is only one of the major ideas affirmed by these traditions.

Second, in addition to affirming the intermediate state, both the Catholic and Protestant traditions have also affirmed the necessity of bodily resurrection. That is, both traditions hold that, in the eschaton, Christ will return and raise our bodies from the grave. Again, Aquinas and Calvin make this clear. Aquinas, for example, says, “Further, the members should be conformed to the Head. Now our Head lives and will live eternally in body and soul, since Christ rising again from the dead dieth now no more (Rom. vi. 8). Therefore men who are His members will love in body and soul; consequently there must needs be a resurrection of the body.”4 Calvin agrees, but goes one step further by adding that the body we shall receive in the resurrection will be the same body that we currently possess. He says that we must believe “that as to substance we shall be raised again in the same flesh we now bear.”5

Thus, generally speaking, the major traditions of Christianity have affirmed two major ideas regarding life after death for Christians: the soul’s presence with Christ in the intermediate state and bodily resurrection in the eschaton. There are, however, concerns with both of these ideas. For the intermediate state, the concern revolves around the existence of the soul. Since the intermediate state suggests a time of disembodied existence in Christ’s presence, it requires the existence of something immaterial about human persons to persist. Most commonly, Christians have pointed to the existence of an immaterial soul as what makes such disembodied existence possible. In other words, when Granny dies and we go to the funeral, we might hear the pastor suggest that Granny is not here. He might say, for example, “Her body is here, but her soul is in heaven with Christ.” On this account of Granny’s person and death, she is composed of body and soul, and at death the two are separated, with one remaining behind and the other moving on to the heavenly realm. Hence this view depends on the existence of an immaterial soul to account for the intermediate state. Yet, as we saw in chapter 11, there are questions about the existence of the soul. For materialist accounts of human persons, there is not a soul, since persons are composed of nothing beyond their physical bodies. If this account is true, then Granny’s soul is not in the presence of Christ, since it does not exist in the first place. To be clear, materialists have their reasons for taking this position. As we saw, the difficulties surrounding mind-body interaction seem to suggest that materialism might be true. So if a Christian account of life after death is correct, it seems as though a defense of the soul is required.

A second problem for the Christian account of life after death concerns the possibility of bodily resurrection. Christians almost universally affirm this possibility. Yet, at the same time, none of us have ever experienced such a strange phenomenon. Moreover, it seems like this could actually be impossible given what we know about the decomposition of human bodies in the grave, in cremation, in cases of cannibalism, or in other cases where a body might be completely obliterated by some natural process. In short, how can the same body come back in the eschaton if it is completely destroyed through one of the processes described above?

These are two of the major problems that must be addressed to support a Christian view of life after death. In what follows we shall offer a brief account of how the Christian view of life after death might be defended.

Arguments for the Soul

So what about the soul? In chapter 11 we outlined the various views that philosophers and theologians have taken over the years. Some of those views affirm the existence of the soul, and some do not. We are now interested in seeing if there are perhaps good reasons for thinking that such a thing actually exists. Over the centuries dozens, or even hundreds, of different kinds of arguments have been offered for the soul. Obviously, we cannot look at all or even most of those arguments. Instead, we will simply focus on a few arguments that have either been very popular or that we think have considerable merit. Here are a few that could be set forth to contend for an immaterial soul.

An Argument from Doubt

René Descartes (1596–1650) is sometimes referred to as the father of modern philosophy. The reason for this is that his work launched the modern emphasis on epistemology and, as a corollary, a major interest in mind-body relations. Growing ever more suspicious about the possibility of gaining sure and certain knowledge, he set out to find a foundation for knowledge that was completely trustworthy. He recognized that it was at least possible that all his perceptions were illusions. To see if he could overcome this possibility, he chose to doubt everything that was possible to doubt in an attempt to find any particular idea or ideas that were sure and certain. Of particular suspicion was the knowledge we gain of the physical world through our senses. He noticed that our perceptions are sometimes wrong and thought that we should not place much confidence in the information derived from them. Hence he admitted that it was possible that all of his beliefs about the physical world could be wrong. Because of this, all of our beliefs about the physical world should be doubted. He could doubt the tree in front of him, the lake beside him, the person speaking to him, and so on.

With great consistency, Descartes also considered his physical body. As a physical object, it too could be nothing more than an illusion. But here Descartes stumbled on an important idea. While he could doubt that his body existed, he could not doubt that he existed. For to doubt is to think, and to think requires that he must exist to think. With this Descartes gives one of the most well-known statements in the history of philosophy: “Cogito ergo sum [I think, therefore I am].” The fundamental idea here is that bodies are of such a nature that they can be doubted, while souls/minds are of such a nature that they cannot be doubted. Therefore, souls/minds are different things. We could state the argument this way:

- All physical objects are such that they can be doubted.

- My body is a physical object, and thus I can doubt it.

- My soul/mind is such that it cannot be doubted.

- My soul/mind is distinct from my body.

- Therefore, my soul/mind exists.

Premise 1 seems rather straightforward and intuitive. If premise 1 is true, then premise 2 would also be true. The key premise here is premise 3. As Descartes points out, the very act of doubting requires a being to do the doubting. Thus while it is possible to doubt our physical bodies, it does not seem possible to doubt our souls/minds.

Philosophers are divided on this argument. Advocates believe that the argument has intuitive appeal, while critics suggest that perhaps there is a bit of smoke and mirrors being employed. While they agree that “something” must exist to doubt, they do not believe that Descartes has shown us that it must be an “I” or a soul/mind. We (the authors) remain convinced that this thing that thinks and doubts is in fact the mind or the soul.

An Argument from Persistence of Personal Identity

Another argument for the soul comes from the fact that persons persist across time even as their bodies experience change. Consider, for example, that a person named Bob lives from 1976 to 1988 and perhaps beyond. During his life, his body is constantly changing parts through the regular metabolic process of eating food and discarding waste. Over a sufficient amount of time, his body replaces the parts that compose his body. Yet, through this process of change Bob continues to exist and to be the very same person he was at an earlier time. What is it that allows his identity to continue? Advocates of the soul could argue that it is the soul that allows Bob to continue existing. We could put an argument along these lines of thought this way:

- Bob exists in 1976 and his body is composed of parts a, b, c.

- Bob exists in 1980 and his body is composed of parts b, c, d.

- Bob exists in 1984 and his body is composed of parts c, d, e.

- Bob exists in 1988 and his body is composed of parts d, e, f.

- From (1–4), Bob persists across time from 1976 to 1988 and is the same person at both times.

- From (1) and (4), Bob’s body is composed of completely different parts in 1976 and 1988.

- Bob is, or has, something over and above his physical body.

Premises 1–4 are uncontroversial. They simply state the process of change in Bob’s body throughout the years. Likewise, premise 5 affirms that it is Bob himself who experiences these changes in his body. Premise 6 makes it clear that Bob’s body in 1988 is composed of completely different parts than it was in 1976. Now if such a process takes place, then the conclusion derived in 7 seems to follow: Bob either is, or at least has, something over and above his physical body.

Here again, philosophers differ on the merits of the argument. There is some question about whether the body completely replaces its parts over time. If it does not, then the argument would seem to have a fatal flaw. If it does, then the argument seems to succeed. Just how many of the parts get replaced is beyond our attention here. For now, we note that the body does replace the vast majority of parts at minimum and possibly all of its parts. At the same time, something remains and is consistent throughout the process. We contend that the soul plays a vital role in making this happen.

An Argument from Consciousness

Another argument for the soul comes from the experience of consciousness. Recall that in chapter 11 we introduced the concept of qualia, which refers to a specific kind of mental properties—namely, our experiences of what certain things are like. Or, put another way, qualia are qualities that are felt directly and immediately. When we eat a jelly donut, for example, there is a particular kind of experience that we have. We do not just have a brain event of electrochemical firings when we ingest sugar. Rather, we actually taste the sugar. That is, there is “something that it is like” to taste sugar, and this is very real. Now as we saw in chapter 11, on this basis most philosophers grant a distinction between brain properties and mental properties—what we call property dualism. Yet some philosophers suggest that property dualism does not go far enough.6 They contend that such mental properties likely require a corresponding kind of entity to bear them. In other words, if property dualism is true, then it is likely that some form of substance dualism is also true. We could put an argument for this as follows:

- Human persons have both mental properties and brain properties.

- Mental properties and brain properties are distinct from each other.

- Distinct kinds of properties require corresponding entities as the basis for each property.

- Human persons have both bodies and souls.

Again, premise 1 is rather uncontroversial. It would be rejected by eliminativists (discussed in chap. 11) but would be affirmed by most philosophers. Premise 2 is also rather uncontroversial, though identity theorists might push back against it. Nevertheless, again we find that the majority of philosophers would accept it. The important move of the above argument is in premise 3, which suggests that each kind of property must have a corresponding kind of entity to bear them. So, for example, a physical property will be one that belongs to a physical object. In this case, the physical properties and the physical events that take place in eating a jelly donut are had by and take place in the brain. By contrast, nonphysical properties are had by nonphysical things. In this case, mental properties like qualia are had by immaterial entities like souls. As Richard Swinburne has put it, “A man’s body is that to which his physical properties belong. If a man weighs ten stone then his body weighs ten stone. A man’s soul is that to which the (pure) mental properties of a man belong. If a man imagines a cat, then, the dualist will say, his soul imagines a cat. . . . On the dualist account the whole man has the properties he does because his constituent parts have the properties they do.”7

There is good reason to think that Swinburne is right about this. Materialist accounts such as eliminativism and identity theory have been unsuccessful in explaining away mental properties and conscious experiences. The various other versions of materialism that allow for the existence of mental properties like qualia have had a difficult time accounting for the way that brains give rise to qualia and mental properties. How is it, exactly, that the neural firings in the brain give rise to the taste of the jelly donut and the feel of the wind blowing through your hair? It looks as though all attempts to explain this within a materialist framework are doomed to fail. Perhaps it is just the case, then, that the existence of mental properties requires the existence of mental substances to have them.

A Case for Bodily Resurrection

If there are good reasons to think that souls exist, then it follows that there are good reasons to think that the intermediate state is also indeed possible. Even if that is so, however, what should we make about the concerns that surround the seeming impossibility of bodily resurrection? Again, as we stated before, the difficulty with this possibility seems to come from what we know about the destruction of our bodies after death from a variety of different causes. If our bodies are completely destroyed, then is it possible for them to be raised from the dead?

To answer this question, we must first get straight on exactly what we mean when we say that the body raised in the eschaton is the “same” as the body that we currently possess. In this case, what does “same” mean? Here an important distinction will help us to navigate the question. Philosophers use the word “same” in at least two different ways. The first is called numerical sameness, which refers to the very same object existing at two different times, even if the object has encountered changes of some kind along the way. In this case, some particular object O2 at t2 is the very same object as O1 at t1. That is to say, a single object O has continued to exist through various moments of time. O2 just is O1 from the earlier moment. Whatever changes might occur in O from t1 to t2 are merely changes in the qualities it has at different moments. This brings us to the second way that philosophers use the word “same.” Philosophers also speak of qualitative sameness, which merely refers to the sameness of qualities that two numerically distinct objects might possess. So, for example, consider two numerically distinct objects A and B that both exist at a given moment t1. Interestingly, A possesses properties x, y, z, and B also possess qualities x, y, z. Therefore A and B share qualitative sameness, even though they are in fact different objects.

A good example that illustrates this distinction even further would be the case of two Ford F-150s that just rolled off the assembly line. Let’s call them no. 1 and no. 2. Then no. 1 will always be no. 1, no matter what dings, scratches, dents, or changes of paint color it might encounter over the years of its life. Likewise, no. 2 will always be no. 2, no matter what dings, scratches, dents, or changes of paint color it encounters over the years of its life. In this case, no. 1 is numerically identical to itself at all points of its life, and the same is true of no. 2. As such, no. 1 and no. 2 are numerically distinct. But now also imagine that no. 1 and no. 2 are qualitatively identical. That is, both no. 1 and no. 2 have exactly the same qualities. They are both white, have an extended cab, have brown leather seats, and are four-wheel drive. Since they possess all and exactly the same qualities (they are physically indistinguishable), they are qualitatively the same, even though they are numerically distinct.

The distinction of numerical and qualitative sameness is deeply influential on the way we answer the question of bodily resurrection. Christianity promises that God will raise our bodies from the grave in the eschaton. Yet we must ask what exactly it is that God must raise. Must the body that God raises be numerically identical to the body we currently possess (i.e., must he raise these exact bodies), or is it only necessary for him to raise a body that is qualitatively the same as the one we currently have (i.e., a physical duplicate)?

How we answer that question of resurrection depends entirely on what we say human persons are. Recall the different views we surveyed in chapter 11. For the substance dualist who affirms person/soul identity (the idea that human persons are just their souls), apparently all that is necessary in the resurrection is for God to raise a body that is a physical duplicate of our current bodies. This is because, on this view, the person just is one’s own soul and is distinct from the body. If so, the current body possessed is not necessary for that person to exist. If this is all that is necessary, then this is very good news, for surely God is able to construct bodies that duplicate the bodies we currently possess. If so, then it really doesn’t matter if our current bodies are completely destroyed. Our existence and identity is not tied to them, so there is not a real resurrection problem.

But what if a duplicate body will not do the trick? What if it turns out that we must have the very same (i.e., numerically identical) body in the resurrection? Such would be the case if it turned out that substance dualism’s person/soul identity claim is false. For example, what if some version of materialism is true and our current bodies are essential to our existence and identity? If so, it would seem that a duplicate body would not secure life after death since a numerically distinct body would yield a numerically distinct person. In this case, while the eschaton might have some person there who looks and acts just like you (a phenomenological duplicate), it’s not you: it’s just a good copy of you. This would be (1) of no comfort for us as we face death and (2) thus a deviation from the promises of Christianity.

Likewise, what if we affirmed the substance dualist’s first claim of stuff distinction (the idea that persons have both immaterial souls and material bodies) but, like materialists, reject the substance dualist’s claim of person/soul identity? In other words, what if a dualist agreed that there is a difference between bodies and souls but said that the human person is a composite of both? In this case, some person named Bruce is his body and his soul. He is not just his soul. It seems like this kind of dualist—let’s call this “dualistic holism”—has the same problem that the materialists would have. For both the materialist and the dualistic holist’s account of resurrection, what is required is a numerically identical body in the resurrection. While substance dualists have a rather easy time answering the question of resurrection, the materialists and dualistic holists seem to have a much more difficult time. This is because (1) our bodies often experience total destruction after death, and (2) these views require us to get those very same—numerically identical—bodies back. The million-dollar question is whether this is really possible.

As Caroline Bynum Walker notes, one of the most common and popular answers to these questions in the early church was the reassembly model of resurrection.8 On this model, God secures numerically identical bodies for us in the resurrection by going out, retrieving all the old parts that used to compose our bodies, and then reassembling them together into the previous order and structure that once composed our current bodies. In short, God just puts us back together and then reunites our souls (which have been in the presence of Christ in the intermediate state) with the reassembled bodies. As a result, the very same person, Bruce, is once again alive and will now live again forever and ever.

As straightforward and simple as this model seems to be, it does have a rather significant problem that is as old as the theory itself. Namely, what would happen if Bruce’s old parts came to compose some other person’s, Keith’s, body? Perhaps after Bruce died, his body decomposed in the ground, its parts were sucked up as nutrients for an apple tree, and Keith ate one of the apples. It looks as though some parts that once composed Bruce’s body now compose Keith’s body. In the resurrection, it looks as though God cannot give the numerically same parts to both Bruce and Keith. This same objection dates back to the time of Athenagoras (AD 133–190). Stated in provocative (and somewhat creepy) form, Athenagoras’s critics put forward what has come to be known as the cannibal objection. Athenagoras says, “Then to this they tragically add the devouring of offspring perpetrated by people in famine madness, and the children eaten by their own parents through the contrivance of enemies, and the celebrated Median feast, and the tragic banquet of Thyestes; and they add, moreover, other such like unheard-of occurrences which have taken place among Greeks and barbarians.”9 He later adds, “From these things they establish, as they suppose, the impossibility of the Resurrection, on the ground that the same parts cannot rise again with one set of bodies, and with another as well; for that either the bodies of the former possessor cannot be reconstituted, the parts which compose them having passed into others, or that, these having been restored to the former, the bodies of the last possessors will come short.”10

So what about the scenario that Athenagoras describes? The cannibal objection points to a problem whereby two persons both end up being composed of the same set of parts at different times. For example, what if Bruce’s body was composed of parts a, b, and c at the last moment of his life, when he was murdered by Keith, and that on murdering Bruce, Keith decided to eat Bruce’s body, thereby consuming parts a, b, and c. Now that Keith’s body is composed of parts a, b, and c, it looks as though there is a significant problem for the reassembly model of bodily resurrection. In short, now that two persons’ bodies are composed of the numerically same set of parts at the last moments of their lives, it seems impossible that God could raise them both via reassembly and give them both the same sets of parts. One set of parts can constitute only one physical body, not two. Several contemporary philosophers consider this objection to be a defeater for the reassembly model of resurrection.11

Despite the difficulties that the reassembly model faces, Christian philosophers have not rejected the possibility of life after death in a physical body. They simply offer some alternative ways that such a thing could take place. Philosophers like Peter van Inwagen, Dean Zimmerman, and Kevin Corcoran, for example, offer two different possibilities for life after death in our physical bodies. Before describing two popular examples of this, however, two notes of clarification about their suggestions are vital. First, their accounts are not necessarily accounts of “resurrection” per se. Rather, they are accounts that allow for our bodies to survive the death event in such a way that we can resume living in these bodies in the life to come. Second, their suggestions are offered only as merely logical possibilities. In neither case do they think that what they describe is what will actually happen.

So why take such an approach? As van Inwagen declares, “What is important is that God can accomplish it this way or some other [way].”12 Both van Inwagen and Corcoran contend that such responses disprove the naturalist’s claim that “it is impossible” for us to survive death if (1) we need our bodies to survive and (2) our bodies get destroyed through some process or another. The “logically possible” response they offer helps us to identify at least a few ways that it is possible. If we can figure a few ways that it is possible, then surely a God who is omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly wise can figure out a better way to bring this about. As such, one need not necessarily endorse these approaches in order to use them against the naturalist’s accusation that embodied survival of death is impossible given what we know about decomposition and destruction of our physical bodies after death. With these clarifications out of the way, we now consider two different examples of logically possible accounts of bodily persistence.

Brain-Snatching Model

Van Inwagen is a Christian materialist about human persons. He rejects the soul and argues that human persons are the life events that are to be identified with their living organisms. Like others, van Inwagen argues that material beings, such as human persons, continue to exist over time via immanent causal connections. On this view, person P persists over time via the causal sequences of P1 at t1 causing P2 at t2, P2 at t2 causing P3 at t3, P3 at t3 causing P4 at t4, and P4 at t4 causing P5 at t5 to exist. So, in other words, the persistence of P over a span of time from, say, t1 to t5 would be as follows:

Persistence = P1 → P2 → P3 → P4 → P5 . . .

On this view, a person P persists over time as long as that person’s living organism continues in the causal sequence of personal life and is uninterrupted. If, however, that life is disrupted (i.e., ended in such a way that the individual’s organism is disassembled), then that person does not continue. On such an account, van Inwagen rejects the reassembly model of bodily resurrection, arguing that the deconstruction of a person P’s body brings an end to that life and therefore breaks the possibility of it causing the organism to persist. Once the life of a person P has ended, van Inwagen believes that it is impossible for P to come back into existence. He says, “If a man should be totally destroyed, then it is very hard to see how any man who comes into existence thereafter could be the same man.”13 As he goes on to explain, any reassembled body in the resurrection would be a person, called Q, numerically distinct from the current person P, even if Q looked just like P and was assembled out of P’s old parts.

Two important points need to be noted about van Inwagen’s view. First, he is a materialist about human persons, which means that for P to survive her death, P must have a numerically identical body to the current body. A duplicate body will not achieve life after death. Second, for P’s body at a later moment to be numerically identical to the current body, there cannot be any temporal gaps in P’s life. In other words, the person cannot stop existing. For both of these reasons, van Inwagen thinks that reassembly will not do. So to solve the problem, van Inwagen suggests the logical possibility of brain snatching: “Perhaps at the moment of each man’s death, God removes his corpse and replaces it with a simulacrum which is what is burned or rots. Or perhaps God is not quite so wholesale as this: perhaps He removes for ‘safekeeping’ only the ‘core person’—the brain and central nervous system—or even some special part of it. These are details.”14 Again, van Inwagen’s point is to say that it is logically possible that such a thing as this could happen. And if this brain-snatching model could be possible, then surviving death is not impossible. If it is not impossible, then it is something that God can do, and Christians are justified in believing in life after death.

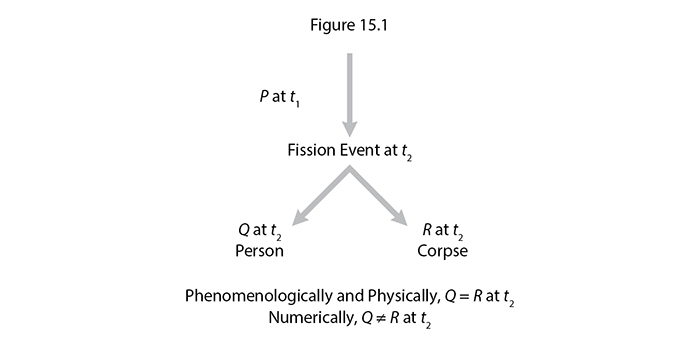

Other philosophers like Dean Zimmerman15 and Kevin Corcoran16 have suggested an alternative way—the body-fission model—to allow for P to survive death if numerical identity is required and there cannot be any temporal gaps in P’s life. Suppose, they say, P’s body exists at some point (t1) prior to a fission event. Then, at t2 just prior to death, P’s body experiences a fission event (it splits into two different bodies). That is, at t2, God allows every particle of our bodies to divide into two distinct particles, and this fission event of particles thereby produces two sets of particles so that each set looks the same as P’s body prior to the fission event. Let’s call these later bodies produced by the fission event at t2 bodies Q and R. Suppose further, they say, that one of these sets of particles, Q, “takes” the life of P and the other set, R, does not. We could diagram this as shown in figure 15.1.

If such were the case, then Zimmerman and Corcoran believe that the materialist should have everything needed to account for surviving death and continuing the life of P. In this case, they have provided a logically possible way that a body could survive death that is immanently and causally connected to the previous body, making it possible to say that the surviving body Q is numerically identical to P and that it did not experience a temporal gap.

Again we should emphasize that such proposals are given only as a way to demonstrate logical possibilities and thus the real possibility of our bodies surviving death. So if we can figure out a way that it could happen, no matter how unlikely our account may be, then surely God can figure out a way to make it happen. As mentioned above, what these accounts give us are not accounts of resurrection per se but rather a demonstration of the logical possibility of our bodies surviving death. As such, if these accounts are successful, materialists might have everything they need to account for life after death.

Back to Reassembly

While the brain-snatching and body-fission models might give us a way for a body to survive death, they do not give us a resurrection. The concept of resurrection entails the idea of a body experiencing death (possibly even being completely destroyed) and then coming back to life at some later time. Therefore, although the brain-snatching and body-fission accounts might argue for some kind of postmortem survival, they do not seem to do justice to the concept of resurrection. Hence, once again, we turn to consider whether the reassembly model should be dismissed so quickly. As we saw, the major problem of this model comes from the possibility that two different physical bodies might be composed of the same set of parts at different times. As the cannibal objection highlights, if the parts that once composed Bruce’s body now come to compose Keith’s body, then it looks as though God has a problem for resurrecting them both via the reassembly model. After all, God can’t give back the same parts to both Bruce and Keith. What should we make of this problem?

Space will allow only a short response to the problem. We admit that the scenario outlined by the cannibal objection is a genuine problem under certain conditions. The question that must be asked is: In order for two bodies separated by time to be numerically identical to each other, must they possess all and exactly the same set of parts? Let’s call this the “all-and-exactly principle.” In other words, suppose that A at t1 is made up of parts a, b, c, and d. If B at t2 is to be numerically identical to A at t1, must B at t2 also be made up of parts a, b, c, and d? If the answer to that question is yes, then it looks like the cannibal objection defeats the reassembly model. But is the all-and-exactly principle true? Perhaps it is not. What about the changes our bodies experience over time through the normal metabolic process of eating food and eliminating waste? It looks like our bodies are constantly changing parts while also maintaining numerical identity. In other words, our bodies change parts without ceasing to be the very same bodies they were at some earlier time. If so, then our current bodies are not composed of all and exactly the same set of parts that once composed them.

So what does this mean for the reassembly model? At minimum, it looks like the cannibal objection is not the defeater for reassembly that some have thought it to be. Perhaps it is not necessary for God to use all and exactly the same set of parts in our reassembled bodies as were once present in our original bodies. Perhaps all that is needed is a sufficient set of the original parts for the eschaton body to be the resurrected body. If those are real possibilities, then it looks like the reassembly model is still in play.

Conclusion

In this chapter we sought to provide a rationale for a Christian view of life after death. As we saw, such an approach requires us to affirm at least two things. First, it requires us to say something about the possibility of disembodied existence in the intermediate state. Such a possibility requires an immaterial soul, and so we explored various arguments in favor of the soul. Second, a Christian view must also say something about the possibility of bodily resurrection. Here we saw that while the accounts of van Inwagen and Corcoran provide us with a logical possibility of how our bodies might survive death, they are not actually accounts of resurrection. We have also argued that despite the traditional concerns about the reassembly model of resurrection, it is not at all clear that such a model is implausible. It looks as though there is sufficient ground for the possibility of life after death.

1. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Notre Dame, IN: Christian Classics, 1947), 3.69.2, supp.

2. John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960), 3.25.6.

3. Calvin, Institutes 3.25.6.

4. Aquinas, Summa Theologica 3.75.1 (emphasis in original).

5. Calvin, Institutes 3.25.8.

6. See Dean Zimmerman, “From Property Dualism to Substance Dualism,” in Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary vol. 84 (2010): 119–50.

7. Richard Swinburne, The Evolution of the Soul (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 145.

8. See Caroline Bynum Walker, The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

9. Athenagoras, The Resurrection of the Dead, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2004), 2:151.

10. Athenagoras, Resurrection of the Dead, 2:151.

11. Trenton Merricks, “How to Live Forever without Saving Your Soul: Physicalism and Immortality,” in Soul, Body, and Survival: Essays on the Metaphysics of Human Persons, ed. Kevin Corcoran (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 186–87; Kevin Corcoran, Rethinking Human Nature (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 124–25.

12. Peter van Inwagen, “The Possibility of Resurrection,” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 9, no. 2 (1978): 121.

13. Van Inwagen, “Possibility of Resurrection,” 118.

14. Van Inwagen, “Possibility of Resurrection,” 121.

15. Dean W. Zimmerman, “The Compatibility of Materialism and Survival: The ‘Falling Elevator’ Model,” Faith and Philosophy 16, no. 2 (April 1999): 194–213. Unlike van Inwagen and Corcoran, Zimmerman is not himself a materialist about human persons. He simply offers this as a way to achieve bodily survival for our physical bodies.

16. Kevin J. Corcoran, “Persons and Bodies,” Faith and Philosophy 15, no. 3 (July 1998): 324–40; and Corcoran, “Dualism, Materialism, and the Problem of Postmortem Survival,” Philosophia Christi 4, no. 2 (2002): 411–25.