16

Metaethics

In the Republic, the question arises, Why be moral? What if, Plato asks, you had a magic ring that made you invisible?1 Would you still be moral if you could do whatever you wanted without being found out or penalized? Plato’s own conclusion, after a good deal of dialogue, is that the moral life is inherently valuable. We ought to be moral, according to Plato, because being moral is a great good: the moral life is intrinsically worthwhile.

How you answer this question depends a great deal on your view regarding the nature of reality. For Plato, there is a moral dimension to reality; moral properties are part of the furniture of the world. To put this another way, if you, like Plato, think that, in addition to physical facts, there are mind-independent moral facts, then you will likely think the answer to our question is something to be discovered. The answer depends on the way the world is. If, however, you think that either there are no moral facts or that all moral facts are mind-dependent in some way (indexed to what an individual or group of individuals believe), then you will be tempted to think morality is, in an important sense, an invention.

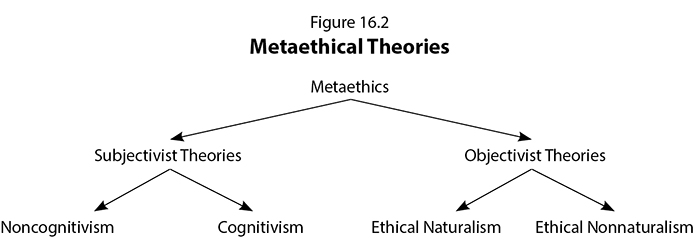

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that explores morality. The field of ethics can be subdivided into two main areas: normative ethics and metaethics (see fig. 16.1). Normative ethics attempts to answer moral questions and settle issues of what to do or how to be. Examples of moral questions that normative ethics tries to answer include: What makes an action morally right or wrong? What kind of person ought I to be? Is abortion wrong? Is homosexuality permissible? Is courage a virtue? Metaethics, however, attempts to answer nonmoral questions about morality. The question of why to be moral is a metaethical question: in asking the question, we are seeking reasons why one ought to adopt the moral point of view.2 This chapter will focus on metaethics.

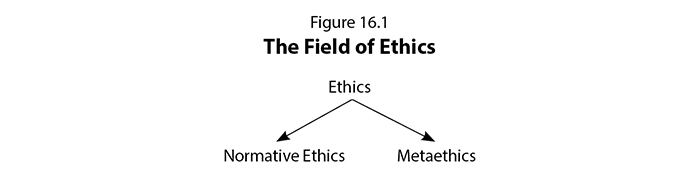

In this chapter we survey prominent metaethical theories, noting each theory’s account of the nature and existence of moral facts (moral metaphysics), the meaning of moral statements (moral semantics), and the justification for and knowledge of moral statements (moral epistemology).3 A helpful way to think about subdividing metaethical theories is in terms of the theory’s fundamental view of morality as either invented or discovered.4 Subjectivist metaethical theories are antirealist and regard morality as invented. Objectivist metaethical theories, alternatively, are realist and regard morality as discovered. Subjectivist metaethical theories can be further subdivided into noncognitive and cognitive, and objectivist metaethical theories can be further subdivided into naturalist and nonnaturalistic (see fig. 16.2).

As we consider each theory, noticing costs and benefits along the way, it will be argued that theistic nonnaturalism is the rationally preferred theory, best accommodating the curious facts, as C. S. Lewis maintains, that “human beings . . . ought to behave in a certain way, . . . [and] they do not in fact behave in that way.”5 We depart from our usual approach of offering an opinionated introduction to the philosophic topic under discussion since in this chapter we are building toward the moral argument for God and will make the case for its soundness.

Subjectivist Theories

Subjectivist metaethical theories all agree that moral properties are not part of the mind-independent world. Rather, morality is grounded in the beliefs (cognitive states) or attitudes (noncognitive states) of individuals or groups of individuals. When it comes to the nature and meaning of moral statements, noncognitivist and cognitivist theories significantly differ. The noncognitivist denies, whereas the cognitivist affirms, that moral statements are indicative statements and thus can be either true or false. Consider the sentence “The dog is brown.” This sentence is in the indicative mood: it purports to be about reality. It asserts the existence of a particular substance—a dog—that has a property, being brown. The sentence has, as philosophers like to put it, ontological import. Additionally, as an indicative sentence, it can be either true or false.

In the same way, it is natural to think that moral statements, such as the sentence “Murder is wrong,” also have ontological implications and can be either true or false. The noncognitivist denies all of this. Moral statements are not indicative: they do not represent reality. Since moral statements do not express genuine facts, they cannot be either true or false.

Noncognitivism

Two prominent versions of noncognitivism are emotivism and prescriptivism. According to emotivism, moral statements are expressions of emotion. To say “Murder is wrong” expresses a feeling of disapproval toward murder. Alternatively, to say “Truth-telling is right” expresses a feeling of approval toward truth-telling. As the prominent twentieth-century emotivist A. J. Ayer puts it, “The function of the relevant ethical word is purely ‘emotive.’ It is used to express feeling about certain objects, but not to make any assertion about them.”6

According to prescriptivism, moral statements function as commands: “Murder is wrong” means “Do not murder”; “Truth-telling is right” means “Tell the truth.” Moral statements, for the prescriptivist, are imperatives that prescribe actions.

Noncognitivism fails to adequately account for the nature of morality for at least three reasons. First, the denial that moral statements can be true or false is problematic. The claim that “It is wrong to kill babies for fun” is plausibly true. The claim that “It is right to dedicate one’s life to the counting of peas in a pan” (as the asthmatic Spaniard did in Camus’s The Plague) is plausibly false. That we are sometimes correct and incorrect in our moral judgments attests to the reality of genuine moral facts.7 But if noncognitivism is correct that there are no moral facts, then our moral judgments regarding such things as the torture of babies and a life devoted to counting peas are beyond reproach, mere expressions of attitudes, which cannot be true or false. This result, to say the least, is counterintuitive.

Second, noncognitivism fails to adequately capture the nature of moral disagreement. Since moral judgments lack cognitive content, moral disagreements are recast as being about what to do instead of about what to believe. But notice that the noncognitivist cannot offer reasons for one course of action over another. Moral disagreements become, as Alasdair MacIntyre explains, “a clash of antagonistic wills, each determined by some set of arbitrary choices of its own.”8 But our actual moral discourse suggests otherwise. There is a “nearly universal appearance” in moral disagreement of “an exercise of our rational powers.”9 In other words, the fact that we argue for the truth of our moral statements is hard to square with the claim, made by the noncognitivist, that moral disagreement is merely a clash of wills, devoid of rational content. Any metaethical theory that removes even the possibility of rational engagement from our moral discourse is implausible, oversimplifying the nature of moral arguments and reducing attempts to influence behavior to a form of manipulation.

Finally, there is the “embedding problem,” the problem of figuring out the meaning of complex sentences that embed simpler moral sentences and moral terms.10 Consider conditional sentences, such as “If Brett Favre throws the ball, then the Green Bay Packers will win.” Conditional sentences are complex, composed of two simpler sentences and a connective. In our sample sentence, “Brett Favre throws the ball” and “the Green Bay Packers will win” are the simple sentences, and “if . . . then” is the connective; it connects the two simple sentences into a complex sentence that is a conditional.

The problem for the noncognitivist is that moral terms can appear in conditional sentences without expressing any emotion of the speaker (or prescribing any action). Consider the following argument (inspired by the television show Gotham):

- If murder is wrong, then getting Jim Gordon to murder is wrong.

- Murder is wrong.

- Therefore, getting Jim Gordon to murder is wrong.

The argument appears valid. For the argument to avoid committing the fallacy of equivocation, the moral terms (in this case “is wrong”) must have the same meaning in each of the statements 1–3. However, the moral term “is wrong” expresses disapproval (on emotivism) only in statement 2. The problem is that moral terms don’t function to express disapproval when embedded in complex sentences (such as conditionals). To see this more clearly, if “Murder is wrong” means “Boo! Murder” as the emotivist claims, then the above argument becomes incoherent:

- If “Boo! Murder,” then getting Jim Gordon to “Boo! Murder.”

- “Boo! Murder.”

- Therefore, getting Jim Gordon to “Boo! Murder.”

The challenge for the noncognitivist is to provide an account of moral semantics that enables the meaning of moral sentences to remain the same whether freestanding or embedded. While there are attempts by noncognitivists to meet this challenge, many think this problem, along with the others, renders the theory implausible.11

Cognitivism

Cognitivist views of subjectivist theories hold moral statements to be either true or false. According to simple subjectivism, the truth value of a moral statement depends on the belief of the individual, and the belief of the individual is based on the individual’s psychological state. Thus the truths of morality turn out to be truths of psychology. If Jones believes that the claim “Abortion is wrong” is true, then Jones disapproves of abortion, and “abortion is wrong” for Jones. If Smith believes the claim “Abortion is wrong” is false, then Smith approves of abortion, and abortion is right for Smith. Notice that, according to simple subjectivism, whatever an individual believes to be true is true (for that person).

This feature of simple subjectivism leads to bizarre consequences. First, if mere belief, albeit grounded in a psychological state, is sufficient to make something true, then the individual believer is infallible, not able to go wrong; to believe X (because X is approved) is to make X true. This is why subjectivism is also antirealist: moral truths depend on the subjective states (attitudes and beliefs) of the individual, not mind-independent facts in the world. The problem, however, is that individuals are not infallible. Their fallibility is shown by everyday experience: we can be and often are wrong about many things. Second, simple subjectivism entails relativism, rendering moral disagreement pointless since everyone is right and all beliefs are true by virtue of a person holding them.

Cultural relativism trades individual infallibility for group infallibility. According to cultural relativism, whatever a group of individuals (or usually, the majority of a group of individuals) believe to be true is true for them. Like simple subjectivism, what a group of individuals believes to be true is based on the psychological state of the individuals within the group. For example, the moral judgment that an action is wrong would be true if most members of the relevant group disapproved of the action.

We might ask, however: Is it wise to trade individual infallibility for group infallibility? It seems not. History attests to the fact that groups of individuals have been wrong about many things, including the morality of slavery, the moral status of women or Jews, and the so-called divine right of kings. Moreover, the question of which group of individuals constitute the relevant group for rendering moral judgments is notoriously difficult to specify. Neither simple subjectivism nor cultural relativism offers an adequate treatment of the nature of morality.12 The main difficulty—for all versions of subjectivism—is that the beliefs and various psychological states of individuals or groups of individuals do not provide a firm enough foundation to ground our moral intuitions and experience. For this reason, many are attracted to objectivist metaethical theories that hold morality to be a discoverable feature of the world: morality is objective, something completely independent of anyone’s attitudes or beliefs. It is to objectivist metaethical theories that we now turn.

Objectivist Theories

Objectivist theories are cognitivist and realist metaethical theories: moral judgments express beliefs that can be true or false, and these beliefs are about discoverable features of the world. For example, according to objectivist theories, the claim “Murder is wrong” picks out a genuine moral property, the property of being wrong, that attaches to the act of murder, and the moral judgment is true if in fact murder is wrong. Likewise, the claim “Truth-telling is right” picks out a genuine moral property, the property of being right, that attaches to the act of truth-telling, and the moral judgment is true if in fact truth-telling is right.

Granted, this moral reality is a bit mysterious: moral facts seem to be different from everyday physical facts. Still, the objectivist argues, belief in the reality of a distinct moral realm is justified in order to make sense of our common beliefs regarding morality.13 The two major versions of objectivist theories differ on the nature of moral properties. The ethical naturalist says the moral properties we ascribe to persons or acts are not as mysterious as they initially appear: rather, they are reducible to natural (meaning nonmoral) properties. The ethical nonnaturalist, however, says moral properties are irreducible.

Ethical Naturalism

Attempts to reduce or define one thing in terms of something else are common in philosophy. In the debate over properties, for example, the nominalist attempts to reduce properties to classes of charactered objects (class nominalism) or classes of objects that resemble charactered objects (resemblance class nominalism). In philosophy of mind, some materialists offer a reductive analysis of mental properties in terms of physical properties; mental properties are just C-fiber firings in the brain. In the debate over causation, the Humean offers a reductive analysis of causation in terms of one type of event regularly following another type of event; causation is just the regular succession of types of events. In these examples, and many others, X is reducible to Y if and only if X can be defined by or identified with Y.

For the ethical naturalist, moral properties are identified with natural properties, properties that are the subject matter of the natural sciences such as biology, psychology, or sociology. For example, the term “right” in the moral judgment “X is right” could mean one of the following, according to the ethical naturalist: “conducive for survival” or “pleasurable” or “what is approved by most people.”14 A virtue of ethical naturalism then is that moral properties are not so mysterious after all. They are safely located within the bounds of the naturalistic universe, empirically measurable in the same way that other natural properties, such as mass and velocity, are measurable.

The main problem with ethical naturalism is that it doesn’t adequately account for the normative nature of morality. Given the fact that cheating is wrong, it follows that you ought not to cheat. Given the fact that it is right to keep promises, it follows that you should keep your promises. In other words, when we make moral judgments, there is an inherent oughtness to the judgment, and it is for this reason that we rightly ascribe blame or praise to our actions. The problem for the ethical naturalist is that natural properties are not normative: they don’t motivate us in the right way. They don’t tell us what we ought to do or what is worth pursuing or what reasons we have for doing anything. Normativity is the ethical naturalist’s Achilles’ heel, according to the philosopher Alvin Plantinga: “There is no room, within naturalism, for right and wrong, or good or bad.”15 Given the action-guiding nature of moral properties, there are good reasons to think they are not natural properties. In other words, if moral properties exist, as the moral realist insists, then there are good reasons to think they are nonnatural.

Ethical Nonnaturalism

Throughout the mid-twentieth century, ethical nonnaturalism was not viewed as a viable option. Of late, however, due to the work of Russ Shafer-Landau and Terence Cuneo, ethical nonnaturalism is making a comeback.16 It is now considered a metaethical view worthy of serious consideration.

Shafer-Landau’s central claim is that there are moral truths and moral properties that exist as fundamental aspects of reality and are discoverable a priori. We don’t discover the morality of genocide or rape, for example, by empirical methods. Thus moral judgments and moral properties are not reducible to the deliverances of the natural sciences. There are sui generis nonnatural moral properties that are intrinsically action-guiding.

Versions of ethical nonnaturalism divide, however, on the question of how to best account for moral properties. The theistic ethical nonnaturalist claims that God’s existence is the best explanation for moral properties. The atheistic ethical nonnaturalist, alternatively, argues that moral properties are brute realities; there is no need to postulate a divine being in order to account for objective morality. In the remainder of this chapter, we shall consider the relationship between God and morality. In doing so, we also fulfill a promissory note issued in chapter 12 to further explore the moral argument for God’s existence.

The moral argument for God can be formulated as follows:

- If God does not exist, there are no objective moral properties.

- Objective moral properties exist.

- Therefore, God exists.

Moral arguments for God have a rich history, defended by thinkers as diverse as Plato, Aquinas, and Kant, and more recently by C. S. Lewis, Richard Swinburne, William Lane Craig, and Mark Linville.17

The moral argument begins by highlighting the inadequacy of atheism to ground objective morality: if God doesn’t exist, then there are no objective moral properties. Atheists who think objective morality stands or falls with the question of God are not hard to find. The atheist Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), for example, argues that if God does not exist and humans are just the “outcome of accidental collocations of atoms,” then there is no objective morality.18 All we can do, according to Russell, is build our lives on “the firm foundation of unyielding despair.”19 Russell’s way out of the moral argument, then, is to reject premise 2 and the claim that there are objective moral properties. Russell argues that moral properties are subjective; morality is a matter of personal taste. But what if the atheist is convinced of moral realism and thus accepts premise 2? Are there plausible atheistic accounts of morality that do not require the existence of God as the ontological ground of objective morality? In other words, what resources are available to the atheist to plausibly deny premise 1?

As might be expected, there are naturalistic and nonnaturalistic attempts to ground objective morality apart from God. The most plausible naturalistic attempt to ground objective morality appeals to human flourishing. On this view, the “good” is whatever contributes to human flourishing, and the “bad” is whatever doesn’t. The problem with this view is that it is arbitrary and implausible.20 It is arbitrary because, given atheism, it is hard to justify giving priority to humans instead of aardvarks or ants. Given the conjunction of naturalism and atheism, there is no difference in intrinsic value between any species. Thus there is no good reason to think human flourishing, as opposed to aardvark or ant flourishing, is the relevant domain for morality.

The attempt to ground morality in human flourishing is implausible because it is not always the case that what contributes to human flourishing is good and what doesn’t is bad. Consider the police officer who, in order to quell a citywide riot, has to kill one vigilante.21 Surely quelling a citywide rebellion is conducive to human flourishing if anything is, yet it would be wrong for the police officer to kill one vigilante to satisfy the mob’s lust for blood. Alternatively, consider the firefighter who rushes into a burning building to save a child. The child’s life is spared, but both the child and the firefighter are badly burned and will suffer a great deal for the rest of their lives. It would seem that the act of rushing into the fire, while conducive to human survival, was not conducive, in this case, to human flourishing, yet no one would argue that what the firefighter did was bad. Thus the atheist’s attempt to ground morality in human flourishing gives us the wrong result.

The most plausible atheistic attempt to ground objective morality is, in our view, Platonic Atheism. Erick Wielenberg argues for a metaethical view amenable to Platonic Atheism called “non-natural non-theistic moral realism.”22 It is a version of moral realism because it endorses objective moral properties. It is nonnatural in that it endorses the view that brute ethical facts and properties are sui generis, not reducible to purely natural facts and properties. It is nontheistic because objective moral properties do not require a theistic foundation. While Wielenberg’s nonnatural nontheistic moral realism doesn’t entail atheism (a theist could endorse such a view),23 it does provide another option for the atheist to respond to premise 1 of the moral argument. Add to Wielenberg’s nonnatural nontheistic moral realism the claim that God does not exist, and the result is Platonic Atheism.

If Platonic Atheism is true, then premise 1 in the moral argument is false. Objective morality is a brute fact. As Wielenberg puts it: “[Basic ethical facts] are the foundation of (the rest of) objective morality and rest on no foundation themselves. To ask of such facts, ‘where do they come from?’ or ‘on what foundation do they rest?’ is misguided in much the way that, according to many theists, it is misguided to ask of God, ‘where does He come from?’ or ‘on what foundation does He rest?’ The answer is the same in both cases: They come from nowhere, and nothing external to themselves grounds their existence.”24 Since both theists and atheists posit a “bottom floor of objective morality” that “ultimately rests on nothing,”25 there is no reason to prefer the theistic foundation to the atheistic foundation.

In reply, theists such as J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig criticize Platonic Atheism as unintelligible:

It is difficult, however, even to comprehend this view. What does it mean to say, for example, that the moral value justice just exists? It is hard to know what to make of this. . . . Moral values seem to exist as properties of persons, not as mere abstractions—or at any rate, it is hard to know what it is for a moral value to exist as a mere abstraction. [Platonic Atheists] seem to lack any adequate foundation in reality for moral values but just leave them floating in an unintelligible way.26

Wielenberg notes that Moreland and Craig’s objection boils down to two claims: (1) all values are properties of persons, and (2) all values have external foundations. Wielenberg simply rejects both claims: “[Moreland and Craig] provide no arguments for such principles.”27 Moreover, argues Wielenberg, in adopting a version of the divine-command theory, Moreland and Craig violate claim 2, since God is the ultimate brute fact; as a being worthy of worship, the ethical fact of being worthy is also a brute fact. Given nonnatural nontheistic moral realism, according to Wielenberg, “from valuelessness, value sometimes comes.”28

In reply, it should be noted that Wielenberg is partially correct: even in theism there are brute ethical facts. This worry is a bit of a red herring, however. The issue isn’t whether there are ethical brute facts. Explanation must stop somewhere. The salient issue concerns the appropriateness of the stopping point for explanation. The theist argues that God, as a personal being worthy of worship, is the appropriate stopping point for explanation. God exists a se (from himself) as the omniscient, omnipotent, wholly good creator and sustainer of all distinct reality. Therefore moral properties and obligations that attach to finite agents and acts are ultimately grounded in God himself, a morally perfect personal being who is the source of all distinct moral reality.

The issue between the theist and the Platonic Atheist boils down to the question of stopping points. Which is a better stopping point to ground moral facts: God or Platonic moral properties? We find the following consideration persuasive on behalf of theism. Consider that I (Paul) am under no obligation to my chair to weigh less than five hundred pounds. If I did weigh five hundred pounds and sat on my chair and it broke, I would not have wronged the chair. Granted, it would be unfortunate that the chair broke, but I am not obligated to the chair to not sit in it if I were to weigh five hundred pounds. (I might have obligations to myself and others not to weigh five hundred pounds, but not to things such as chairs.) I do, however, have obligations to my students: to tell the truth, to treat them fairly, to not steal their money, and so on. We may ask, Why am I obligated to my students but not to my chair? A plausible answer is that we are obligated to persons, not to things. But according to Platonic Atheism, at rock bottom, my obligations are to things: Platonic moral properties such as the property being just or being honest or being fair and the like. This story strikes many as implausible. We are obligated to people partly because value ultimately resides in persons. Theism accounts for this common moral intuition. Moral properties are ultimately grounded in the supreme person, God himself. The only brute fact is that God exists and has the moral character he has. This, we submit, is the proper stopping place for explanation. Thus theism, and not Platonic Atheism, best explains the fact of objective morality.

It is false that “from valuelessness, value sometimes comes,” as Wielenberg suggests. Rather, reality is fundamentally valuable because God exists and is morally perfect. Moreover, the fact that there is a moral law that we constantly fail to live up to provides further reason for thinking Christian theism to be true, for only in Christianity does God provide the remedy for humanity’s moral failure. Through Christ, a payment has been made for our wrongdoing, and thus the possibility for forgiveness of sins and moral wholeness is offered to all who would believe.

The upshot is this: There is a sound argument from the existence of nonnatural moral properties to the existence of God. Thus, of all the metaethical theories canvassed in this chapter, some version of theistic ethical nonnaturalism is the rationally preferred theory.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have explored the nature of morality and moral statements. The realist thinks that morality is part of the furniture of the world and that moral facts are discoverable. The anti-realist thinks that morality is not part of mind-independent reality; moral facts are invented. We have argued that there are good reasons to think morality is an objective and discoverable feature of the world. We also think, as we have briefly canvassed, there is a good (and sound) argument from the reality of objective moral properties to God. In the end, it is a good thing that God is the source of the moral law even as humans fail to uphold it. Tragedy and failure don’t get the last word. God, in his goodness and mercy, has provided a remedy for our failures through Jesus Christ.

1. Glaucon, Plato’s brother, raises this question in book 2 of the Republic and illustrates the contention that no one is willingly moral with the story about Gyges and the magic ring in 359d–360e. Fans of Middle Earth may be surprised that the idea of an invisibility ring does not originate with J. R. R. Tolkien.

2. The “ought” here is best understood as a rational ought. We are seeking reasons for why someone would be rationally justified in adopting the moral point of view. For more on the distinction between the moral ought and the rational ought, see J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003), 403–4.

3. For a nice explanation of moral semantics, moral metaphysics, and moral epistemology, see Mark Timmons, Moral Theory, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 19.

4. David McNaughton, Moral Vision (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1988), 3–16.

5. C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2001), 8.

6. A. J. Ayer, Language, Truth, and Logic (New York: Dover, 1952), 108. There is a prescriptive element in Ayer’s emotivism: moral statements are also used to stimulate similar feelings in others and encourage them to act accordingly. For another prominent twentieth-century defense of emotivism, see C. L. Stevenson, Ethics and Language (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1944).

7. James Rachels, The Elements of Moral Philosophy, 6th ed., with Stuart Rachels (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 38–39.

8. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 3rd ed. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 9.

9. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 9, 11.

10. Also sometimes called the Frege-Geach problem. For a helpful discussion of the problem, see Mark van Roojen, Metaethics (New York: Routledge, 2015), 149–50.

11. For a nice discussion of noncognitivist responses to the embedding problem, see van Roojen, Metaethics, 150–56.

12. For a more fine-grained discussion of versions of subjectivism that have evolved in response to objections like those noted above, see van Roojen, Metaethics, 99–140.

13. For a nice discussion of the phenomena of morality that lead to a presumption of moral realism—e.g., moral agreement and disagreement, moral mistakes, and moral progress—see Andrew Fisher, Metaethics: An Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2014), 56–60.

14. Moreland and Craig, Philosophical Foundations, 401. For a more detailed discussion of how ethical naturalists go about reducing moral properties to natural properties, including the a priori methods of Frank Jackson’s “Canberra Plan” and the a posteriori methods of the so-called Cornell realists, see Fisher, Metaethics, 60–70; and van Roojen, Metaethics, 210–52.

15. Alvin Plantinga, “Afterword,” in The Analytic Theist: An Alvin Plantinga Reader, ed. James Sennett (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 356, quoted in Fisher, Metaethics, 75.

16. See especially Russ Shafer-Landau, Moral Realism: A Defense (Oxford: Clarendon, 2003); and Terence Cuneo and Russ Shafer-Landau, “The Moral Fixed Points: New Directions for Moral Nonnaturalism,” Philosophical Studies 17, no. 1 (2014): 399–443.

17. Lewis’s classic defense of the moral argument is given in Mere Christianity, chaps. 1–5. See also Richard Swinburne, The Existence of God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), chap. 9; William Lane Craig, Reasonable Faith, 3rd ed. (Wheaton: Crossway, 2008), 172–83; and Mark D. Linville, “The Moral Argument,” in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology, ed. William Lane Craig and J. P. Moreland (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 392–448.

18. Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship,” in Why I Am Not a Christian (New York: Touchstone, 1957), 107.

19. Russell, “Free Man’s Worship,” 107.

20. William Lane Craig, On Guard (Colorado Springs: David C. Cook, 2010), 138.

21. The example is from C. Stephen Evans, Natural Signs and the Knowledge of God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 119.

22. See Erick J. Wielenberg, “In Defense of Non-natural Non-theistic Moral Realism,” Faith and Philosophy 26, no. 1 (2009): 23–41 (emphasis in original). More recently, Wielenberg has dubbed his view “non-theistic robust normative realism.” See Wielenberg, Robust Ethics: The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Godless Normative Realism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

23. See, e.g., Keith Yandell, “Moral Essentialism,” in God and Morality: Four Views, ed. R. Keith Loftin (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2012), chap. 3; and Yandell, “God and Propositions,” in Beyond the Control of God? Six Views on the Problem of God and Abstract Objects, ed. Paul M. Gould (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), chap. 1.

24. Wielenberg, “Non-natural Non-theistic Moral Realism,” 26.

25. Wielenberg, “Non-natural Non-theistic Moral Realism,” 40.

26. Moreland and Craig, Philosophical Foundations, 492.

27. Wielenberg, “Non-natural Non-theistic Moral Realism,” 34.

28. Wielenberg, “Non-natural Non-theistic Moral Realism,” 40n68.