17

Normative Ethics

Roughly speaking, morality is about good and bad action, or, to state it another way, it is about right and wrong. But as we jump into these discussions, we quickly find that things are a bit more complex, since there are unique categories of moral questions and various theories that seek to provide the answers to such questions. For example, in the last chapter we introduced the distinction between two branches of ethical inquiry: metaethics and normative ethics. As we suggested there, metaethics is the branch of ethics that deals with the nonmoral (or perhaps largely philosophical) questions concerning morality. So, for example, metaethics deals with semantic questions about goodness: What does it mean to be good? Metaethics also deals with epistemological questions: How do we know what is good? And finally, metaethics deals with metaphysical moral questions: What is the basis of morality? Why should we be good?

By contrast, normative ethics, the focus of this chapter, deals with questions regarding the “how” of morality. In other words, in normative ethics we concern ourselves most centrally with questions about the way of doing morality. Within this inquiry, normative ethics divides into two further general categories: moral theory and applied ethics. Applied ethics is that branch of normative ethics that tries to answer very specific moral questions like these: Is abortion morally acceptable? How should we treat animals? Is sex before marriage permissible? Should we use the death penalty in the case of murder? Moral theory, the second branch of normative ethics, deals with systems of thought that try to provide a pathway for doing morality itself. Or, as Mark Timmons has put it, moral theory “attempts to answer very general moral questions about what to do and how to be.”1

In this chapter we will explore the branch of normative ethics known as moral theory. We will explore three broad approaches to moral theory, including teleological, deontological, and contemporary virtue ethics. In each case we will outline distinct versions of each approach. We will begin with the teleological accounts of moral theory.

Teleological Theories

When people think about morality, they typically think in terms of right actions, commands, or mandates of some kind. For example, to be moral, one might think, is to avoid doing bad things and instead to do good things. But this is not the way teleological models of moral theory conceive of morality. Indeed, teleological accounts of morality build on the notion of telos (Greek for “purpose” or “goal”), and suggest that morality be thought of in terms of certain kinds of goals or outcomes, not in terms of actions per se. As John Frame explains, “This tradition understands ethics as a selection of goals and of means to reach those goals.”2 But aside from this general point of agreement, as we will see, the selected teleological moral theories seek to achieve this in different ways. Below we outline Aristotle’s virtue account, egoism, and utilitarianism.

Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics

Aristotle was a pupil of Plato and one of the greatest philosophers of all time. He wrote on virtually every discipline possible, including physics, metaphysics, the soul, poetics, rhetoric, politics, economics, and ethics.3 In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle offers his teleological account that builds on the concept of virtue. Like other teleological accounts, Aristotelian virtue ethics begins with a particular kind of outcome or end that we are to seek. In his case, it the notion of eudaimonia, a Greek term often rendered in English as “happiness.” But by “happiness,” Aristotle does not mean pleasure. Rather, eudaemonia (English spelling) suggests something deeper and more meaningful: it means something more along the lines of well-being or excellence of the soul. What Aristotle suggests is that life in general, and morality in particular, is about achieving the goal of eudaemonia. But how is this done? For Aristotle, the answer lies within virtue and virtuous living. But what are virtues, and how do they help us to achieve eudaemonia?

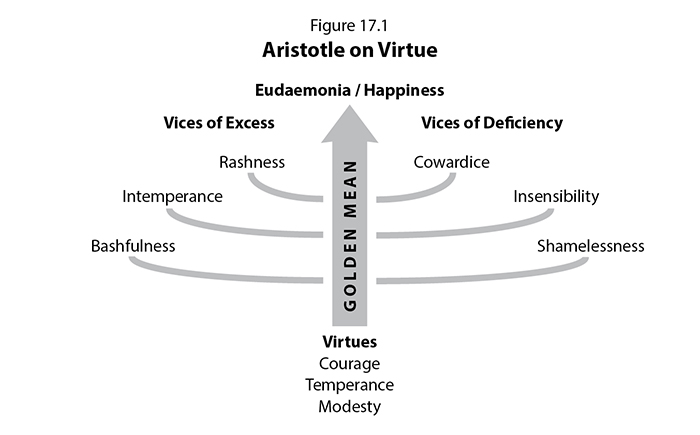

To understand what a virtue is, we must also say something about its opposite, vice. Both virtues and vices are characteristics or qualities of some kind. In other words, virtues and vices are characteristics that are true of us, or qualities that we possess. Even though virtues and vices are characteristics true of a person, there are very different kinds of characteristics that can be true of a person. Simply put, a vice is some negative characteristic of a person that is debilitating, destructive, or problem-producing in nature. If a person has a vice, possessing some negative characteristic, then that person and all the closely connected people will suffer from the difficulties that come in the wake of that vice. So, for example, we might say that a person has a vice of “being quick tempered.” Because of this vice, the person may be prone to lose jobs, destroy relationships, hurt people, or even commit a crime in a rage of anger. The result of the vice is that it hurts or hinders in some way. By contrast, a virtue is some positive characteristic of a person that is life-producing, beneficial, or helpful in nature. If a person has a virtue, some positive characteristic, then that person and all the closely connected people will benefit from that displayed virtue. One other important note should be made about the concepts of virtue and vice. While they are in some sense opposites, they are not necessarily polar opposites, with virtue on one side and vice on the other. Rather, it is better to think of virtue as being situated in the middle, and vice being expressed in two polar opposite directions from it. We could diagram this as shown in figure 17.1.

As the diagram visually lays out, Aristotle recognizes that for each virtue there were two opposing vices that move away from each other. He says that virtue is the “mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency.”4 That is, for each virtue, there are vices of excess and vices of deficiency. Consider, for example, the virtue of courage. There are at least two ways that character can be corrupted in opposition to the virtue of courage. On the one hand, there is the utter lack of courage. Cowardice, for instance, is a vice that opposes the virtue of courage. We call it a vice of deficiency because it lacks what courage provides. On the other hand, the vice of rashness is also an opposing vice to courage. In this case, however, it overshoots the concept of courage by being too eager to fight. Courage then is that middle characteristic between the vices of excess and deficiency. Thus Aristotle refers to virtue as “the golden mean,” since it produces the right qualities of a person set between the vices of excess and deficiency. By virtue—a positive characteristic that is in contrast to a respective vice—one is able to achieve eudaemonia.

One of the benefits of Aristotle’s approach is that it recognizes the need for internal goodness within a person. It is entirely possible for a person to perform good actions and still be rotten on the inside. While such a person may satisfy the expectations and needs of others, surely this is not enough to instantiate true goodness. Aristotle’s contention that the character of a person is vital to goodness is helpful and instructive. Critics, however, have suggested that his system inevitably falls back into some kind of rule-based ethic.

Consider how this might be the case. Suppose I am to develop the virtue of courage. How might this virtue develop in me? It seems that I can’t develop this virtue by simple reflection or will. I can develop this virtue only in situations that call for me to be courageous. So, for example, imagine that I see a bully roughing up a smaller kid on the playground. To be courageous means that I must go and do something about it. I must stand up to the bully and protect the smaller kid. But if this is true, isn’t there some rule that I am obeying after all? Isn’t it the case that I am only courageous inasmuch as I follow the rule of “protecting the weak” and that developing the virtue of courage needs rules for such development? As it turns out, Aristotle was well aware of this issue, and his response demonstrates that his view is actually rather balanced. He recognizes that there are certain kinds of actions that need to be performed and certain kinds of actions that need to be avoided. He says, “That is why we need to have had the appropriate upbringing—right from early youth, as Plato says—to make us find enjoyment or pain in the right things.”5

Egoism

Another variation of teleological moral theory is egoism. This is the view that understands morality in terms of the well-being of oneself. Like other teleological views, it rejects the idea that there is some objective moral standard or set of commands that must be obeyed at all costs; instead, it argues that an outcome of some particular kind is what is important to moral thinking. Unique to this teleological view, however, is the idea that what a person should do is consider one’s own personal interests in the decision-making. While Aristotle’s virtue account was concerned with the well-being of a person, it was not essentially egocentric in the way that egoism turns out. As the twentieth-century naturalist Ayn Rand (1905–82) put it, man “must live for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself. To live for his own sake means that the achievement of his own happiness is man’s highest moral purpose.”6 If such a position sounds radical, it is because it is radical. James Rachels describes it this way: “Ethical egoism does not say that one should promote one’s own interest as well as the interests of others. . . . Ethical egoism is the radical view that one’s only duty is to promote one’s own interests.”7 For many individuals, this radical ethical notion seems hard to accept. But Scott Rae describes the rationale behind it.8 As Rae notes, egoists have typically argued that (1) looking out for others is generally “a self-defeating pursuit,” (2) egoism is “the only moral system that respects the integrity” of individuals, and (3) egoism is the “hidden unity underlying our widely accepted moral duties.”9

Before moving on from egoism, there are two points of clarification about what such a radical view doesn’t entail. First, as Rachels notes, while egoism understands one’s own personal interests as the sole moral principle of concern, this does not mean that egoism is necessarily against helping other people and at times looking out for their concerns. After all, there are certainly times in our lives when helping someone else is actually beneficial to us. For example, I might choose to help the man on the side of the road who has a flat tire because I know that he is president of my company and this would make a good impression on him. Or I might give a sandwich to the homeless person on the street because I know that my companion is watching and will think highly of me for doing such things. So then, as long as helping others helps me in some way, egoism is not against helping others. In this sense, egoism is deeply consequentialist.

Second, egoism also doesn’t entail the idea that we should always do what we want to do, since it is often the case that doing what we want to do can lead to harm for us and go against our best interest as a result. For example, if I always did what I want, I’d have ice cream seven times a day and would be incredibly unhealthy. Or if I always did what I most want, I might sleep until noon every day. But if I did this, I wouldn’t have a job. So then, while egoism makes moral thinking a matter of personal, and only personal, concern, it doesn’t entail that we should never help others or that we should always do what we most want.10

The radical theory of egoism is rather difficult to embrace. Nevertheless, egoism’s contention—that when all is said and done, self-interest is what actually motivates all of our ethical theories—is insightful. Whatever other moral obligations we may affirm, it is true that we are often concerned with ourselves. But this insight is only partial. Sure, we may be motivated by self-interest, but we are also motivated by plenty more beyond that. When a soldier throws himself on a grenade to save the life of his friend, it seems we can safely say two things: (1) such action is morally praiseworthy, and (2) whatever it is that makes it praiseworthy, it is not merely self-interest. Furthermore, as critics have been right to point out, if egoism were universally accepted, it would lead to absolute anarchy and chaos.11 When all we have is concern for ourselves, society is destroyed.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism, initiated by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and popularized by John Stuart Mill (1806–73), is another version of teleological moral theory in that its focus is on the effect of our actions and choices. It contends that morality is judged by the results that follow from our actions, not the nature of the action itself. As such, it rejects the idea of an objective moral standard for our action and locates morality in outcomes. Unlike egoism, however, utilitarianism is concerned with what is good for other people as well as for the self. While egoism is based solely on personal interests, utilitarianism seeks what is in the best interest of the whole (such as a whole group of people). As Bentham puts it, “It is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.”12 Central to this account is the notion of the “utility” of an action. He writes, “By utility is meant that property of something whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered.”13

For Mill, utilitarianism provides a way to think about ethics that doesn’t require metaphysical foundations. As he considered the history of philosophy, Mill was convinced that philosophers before him had failed to provide an adequate moral foundation for objective morality. Because of this, he rejects approaches to morality that search for the ontological basis of right and wrong. And while he admitted that utilitarianism could not be proved or demonstrated, he did believe that this account of morality is justified on the basis of the results it produces. He says:

Whatever can be proved to be good, must be so by being shown to be a means to something admitted to be good without proof. The medical art is proved to be good by its conducing to health; but how is it possible to prove that health is good? The art of music is good, for the reason, among others, that it produces pleasure; but what proof is it possible to give that pleasure is good? If, then, it is asserted that there is a comprehensive formula, including all things which are in themselves good, and that whatever else is good, is not so as an end, but as a mean, the formula may be accepted or rejected, but is not a subject of what is commonly understood by proof.14

Utilitarianism is commendable in that it concerns itself with the happiness and well-being of as many people as possible. With its concern for “many people,” utilitarianism is an improvement on egoism. Nevertheless, it too has its problems. First, this moral theory is unable to ground moral ideals in anything substantial. As the happiness of the greatest number may change, so too will the laws, rules, and actions of society. Can morality really be summed up in a list of rules that (generally) bring felicity to many people? Surely there is something deeper at the heart of morality. Second, utilitarianism never actually says anything about goodness. Third, and building on the first two concerns, without a true account of goodness and a pathway toward it, utilitarianism will be inevitably oppressive to some.

Imagine this example. According to utilitarianism, the “good” and the “right” are determined by whatever brings the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people. Now imagine a society like America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when slavery was the law of the land. The greatest number of people (the white people) were made happy by the forced labor of the minority (the black people). Sure, this approach brings the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people, but is this really what is good and what is right? Surely not!

———

As we have seen, moral theories that are teleological in nature ultimately judge morality in terms of the results of actions and rules. On this account, it is the outcomes of our actions that we are after, and ethical systems must be built to bring about these outcomes. Aristotle’s virtue ethic seeks eudaemonia and sees virtue—the golden mean—as the only way to achieve this. Egoism, by contrast, maintains that our only duty is to look out for our own best interest, but it doesn’t entail that we never help others or that we always do what we most want. The utilitarian ethics of Bentham and Mill seek the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people. Each of these systems has its critics, but each of them has merit as well. We now turn to a different way of doing moral theory: deontology.

Deontological Theories

In contrast to teleological moral theories, which reject the idea of rules, laws, and mandates and develop their approaches to morality in terms of certain kinds of goals or outcomes, deontological moral theories do the opposite. For deontology (from deō, Greek for “ought” or “duty”), ethics is typically thought of in terms of obligation. In these systems, morality is grounded in a set of objective standards that prescribe certain kinds of moral actions. As Rae puts it, deontological “systems of ethics are principle-based systems, in which actions are intrinsically right or wrong, dependent on adherence to the relevant moral principles or values.”15 Noting a key difference between the deontologist and the teleologist, Frame says, “In the deontological view, seeking happiness is never morally virtuous; indeed, it detracts from the moral quality of any action. So when a writer despises pleasure and exalts principle or self-sacrifice, he is probably a deontologist.”16

But as we shall see, not all deontological moral theories are the same. “What distinguishes various types of deontological systems,” Rae states, “is the sources of the principles that determine morality.”17 Rae’s observation is both accurate and helpful. Below we will illustrate this point by exploring deontology and divine-command theory. These two moral theories, while both are deontological, have very different sources for their moral principles. While one looks to the categorical imperative, the other looks to God and the commands that he gives.

Kant’s Deontology

The great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant was one of the leading voices for deontological moral theories. Like other deontologists, Kant sought to ground morality in a fixed set of moral standards and the moral duty that comes from them. But as an Enlightenment philosopher who rejected the possibility of doing ethics on metaphysical or theological foundations, Kant needed to find a way to objectively ground morality without God or the traditional metaphysics of the classical, patristic, and medieval thinkers. Moreover, Kant was equally convinced that such foundations could not be discovered through the empirical observation of the sciences.18 But how could something like this be done? How can we have objective moral standards that are not grounded in theological or philosophical convictions and are also not discovered by empirical science? Kant’s solution was found in a distinction between two kinds of imperatives (commands or moral rules) that we can identify.

On the one hand, Kant considers what he calls the hypothetical imperatives, which have a conditional goodness and operate on an if/then logic. Hypothetical imperatives refer to a set of commands or rules that one must follow if wanting a particular outcome. So, for example, if I want a pay increase for my work, then I should work really hard and go over and above what is expected of me. Notice that the imperative in this example—I should work really hard and go over and above what is expected of me—is not universally applicable. This is an imperative that should be obeyed only in some circumstances—namely, if I want a pay increase. If I do not want an increase in pay, then the imperative is not obligatory. The conditional nature of hypothetical imperatives is too weak to ground morality objectively and as a result cannot be the basis of deontology.

In contrast to hypothetical imperatives, Kant also observed what he called the categorical imperatives, which are unconditional in nature. That is, a categorical (applying to all people everywhere) imperative is a rule or command that is universally and objectively applicable. To identify specific cases of the categorical imperative, Kant suggested the following way of thinking: “Act only according to the maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”19 What Kant suggests here is that the test for determining whether an imperative is hypothetical or categorical is to ask whether we would want that imperative applied to all people in all circumstances. If we would see it necessary to be applied only in some circumstances, then the imperative is merely hypothetical. But if we find that we would want that imperative applied everywhere to all people, then it is a categorical imperative. Given the universal applicability of these imperatives, Kant believes this is the basis of deontology. In this approach, Kant thought that he had provided a nontheological or empirical basis for moral duty that was, nevertheless, universally applicable to all people.

One of the major assumptions in Kantian deontological moral theory is that there is in fact a “universal rationality” shared by all people everywhere. Indeed, this was one of his major assumptions in his entire philosophical system and a central idea within the Enlightenment itself. If it is true that all people everywhere share the same rational patterns of thought and that there really is a universal rationality, then systems like Kant’s may indeed be successful. But, as it turns out, increased globalization, discoveries about the way people in different cultures actually think, and the advent of new intellectual disciplines like psychology, sociology, and anthropology have seriously challenged this assumption. As Alister McGrath puts it, “[The] empirical study of cultural rationalities disclosed a very different pattern—namely, that people possessed and possess contested and at times incommensurable notions both of what is ‘rational,’ ‘true and right,’ and how those qualities might be justified.”20 As the assumption regarding the “universal rationality” began to erode, so too did the confidence that we could develop a deontological moral theory along the lines that Kant suggested.

Another example of a deontological moral theory is what philosophers have called divine-command theory. Roughly, this theory says that morality is grounded in a fundamental way in whatever it is that God commands. Or as Robert Adams suggests, “This is the theory that ethical wrongness consists in being contrary to God’s commands, or that the word ‘wrong’ in ethical contexts means ‘contrary to God’s commands.’”21 Found in versions of several of the major world religions like Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, this view is commonly associated with religious perspectives on morality. But what exactly is it about morality that is supposed to be grounded in the commands of God? Morality is not a one-dimensional issue. Numerous moral dimensions need to be addressed. For example, questions about goodness and obligation are different philosophical questions. What is ultimately good and what we are obligated to do are different aspects of moral theory, and a failure to recognize this will only muddy the water. When we say that God’s commands are what ground morality, are we talking about goodness or obligation?

As Timmons points out, because of questions like these there are actually two different versions of divine-command theory: unrestricted and restricted.22 As he notes, unrestricted divine-command theory seeks to account for both goodness and obligation via God’s commands. On the unrestricted version, (1) we are obligated to do some action A (and avoid others) because God says so, and (2) A is good because God says so. God’s commands are what make A good or bad, and God’s commands are what render us obligated to do A. Critics of divine-command theory typically attack this unrestricted version. One major concern with it is that it seems to make goodness an arbitrary matter. If unrestricted divine-command theory is right, then it is possible for God to flip morality on its head and say the very opposite of what he earlier said. If in this world God said love is good and hate is evil, it would be possible for him to say the opposite, that hate is good and love is evil. This seems hard to square with what we know about God and leaves morality as nothing more than a divine whim or coin flip. Surely a God who is all-knowing, all-wise, and all-good has better reasons for doing what he does than that.

Other advocates of divine-command theory have opted for a restricted version, which says that God’s commands ground some but not all aspects of morality. On this view, what God’s command does ground is our obligation. In other words, God says that we are not to steal or commit adultery. God’s commands are what render us obligated. But this view restricts the grounding of morality to obligation and does not suggest that goodness is grounded in divine commands. Goodness, on this view, is not something that God simply commanded. Rather, it is something that God is. As such, goodness is grounded in God’s nature, not in his commands. And what is more, God’s commands flow out of his nature. So then, when God says you shall not commit adultery, this is not just an arbitrary coin flip on his part. Rather, the command, which does ground our obligation, flows from his own divine nature, which is good and perfect. God commands us not to commit adultery because he wants us to be faithful. And why does God want that? He wants it because he himself is faithful, and we bear his image. This restricted approach, according to its advocates, seems to bypass the concerns raised above with the unrestricted account.

Contemporary Virtue Ethics

So far we have considered teleological and deontological accounts of moral theory. We now turn to contemporary virtue ethics, which, as we will see, is a bit less precise and thus more difficult to fully grasp. By most accounts, this movement in ethics stems largely from the work of Alasdair MacIntyre in After Virtue and Whose Justice? Which Rationality?23 MacIntyre begins with a simple thought experiment. He asks us to imagine that, due to a series of catastrophes that society blames on scientists, riots erupt and the masses seek to destroy the natural sciences from the face of the earth. Laboratories, books, and equipment are burned and destroyed. Scientists are killed, and teaching science in schools is forbidden. For the most part, the masses succeed in destroying modern science. But the masses have not been completely successful, since still remaining are fragments of scientific material and some equipment that survived the destruction. In later generations, some students desire to revive the sciences, and they collect all the remaining artifacts that can be found and begin to attempt reconstruction. The remaining artifacts are enough for them to learn some of the language of science but not sufficient to actually do science or to be successful in their reconstruction. They use the language of “mass,” “relativity,” and “gravity,” but they use that language in a way that differs sharply from the way it was used by scientists prior to the riots and that fails to enable them to actually do science. What is MacIntyre’s point with this thought experiment? He suggests that what is imagined in the thought experiment about science is precisely what has happened with morality in modern times. He says:

The hypothesis which I wish to advance is that in the actual world which we inhabit the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of natural science in the imaginary world which I described. What we possess, if this view is true, are the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived. We possess indeed simulacra of morality, we continue to use many of the key expressions. But we have—very largely, if not entirely—lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.24

MacIntyre believes the current state of morality is in shambles because of the widespread disagreement about what virtue is in the history of Western thought. Whatever else one might think about MacIntyre’s actual virtue ethic, his historical survey of the great thinkers is spectacular. Indeed, he spends much of his time in both After Virtue and Whose Justice? Which Rationality? summarizing and analyzing the ethical thought of ancient, patristic, medieval, and even modern giants. What he demonstrates in the process is that there has been no agreement on what a virtue is, which characteristics are virtues, which virtues are most important, and what virtue’s place in society should be. He asks, “If different writers in different times and places, but all within the history of Western culture, include such different sets and types of items in their lists, what grounds have we for supposing that they do indeed aspire to list items of one and the same kind, that there is any shared concept at all?”25

In his view, what the history of ideas shows us we cannot do is construct a unified approach to morality that applies to all people everywhere. He concludes this from his survey of Western thought alone. Matters only worsen when we bring in Native American, Eastern, and African accounts of morality. The sharp and widespread disagreement over what virtue is makes it impossible to ground morality in any universal or objective way. Or as he puts it, “There is no set of independent standards of rational justification by appeal to which the issues between contending traditions can be decided.”26

But if that is the case, what does MacIntyre suggest we should do? Despite what one might think from the description above, MacIntyre does not (1) disparage the sociotemporal nature of traditions and their respective understandings of virtue or (2) embrace a relativistic notion suggesting that all traditions are intellectually or morally equal. To be clear, he suggests that virtue requires a tradition as a starting point for moral principles.27 We start within a particular tradition and its understanding of virtue and then let our understanding of virtue evolve, change, or even expand as we encounter new data about the world we live in or dialogue with people from different traditions. As such, virtue is not conceived of as a fixed set of moral characteristics. Rather, it is thought of as “an acquired human quality the possession and exercise of which tends to enable us to achieve those goods which are internal to practices and the lack of which effectively prevents us from achieving any such goods.”28

On this view, objective moral principles derived from natural law are not our starting point. Instead, we start with the traditions we inherit and work to improve our understandings of both reality and morality. The intellectual viability of different traditions is judged not by an objective set of intellectual or moral truth, as the Enlightenment suggested, but rather by the ability of a tradition to respond to the problems and inadequacies of its view. MacIntyre describes the process in three stages: “a first [stage] in which the relevant beliefs, texts, and authorities have not been put in question; a second [stage] in which inadequacies of various types have been identified, but not yet remedied; and a third [stage] in which response to those inadequacies has resulted in a set of reformulations, reevaluations, and new formulations and evaluations, designed to remedy inadequacies and overcome limitations.”29

But what does this mean? What MacIntyre suggests here is that some traditions are superior to others given their ability to continue adapting and reformulating in response to new questions, concerns, and objections that are discovered. As new facts about the world are discovered or objections are raised for a tradition from a rival tradition, the superior tradition will be the one that is able to adapt in such a way that it can address those concerns. What this means for our moral theory is that, while we start from within our own unique tradition, we do not leave our understanding of truth and morality as a set of static beliefs that we came to adopt. Rather, we work from within that set of beliefs, learning new facts about the world while in dialogue with rival traditions to sharpen our beliefs through expansion and adaptation.

As mentioned above, MacIntyre is a master of historical intellectual analysis on the question of virtue. As he’s shown us, the history of ideas is indeed filled with various understandings of virtue. His critical work is worthy of serious attention as a result. But some critics have suggested that his own account of virtue collapses into the same kind of problem that he seeks to avoid. The key to his contemporary virtue account is his rejection of the Enlightenment’s notion of a shared universal rationality. But some have suggested that MacIntyre embraces something similar to this regarding his three-stage account for adjudicating between differing traditions. The idea that some traditions are better than others, due to their ability to respond and adapt to new insights and objections, is not an idea that is specific to any particular tradition and thus seems to be an objective criterion. Others have suggested that his approach forces us to reject the idea of absolute truth and, despite his best efforts, results in relativism.

Conclusion

As we have seen in this chapter, normative ethics is the branch of moral inquiry that tries to provide a way of doing ethics or a pathway for being moral. Of normative ethics’ two divisions, this chapter has focused on moral theory. We have sought not to endorse one particular approach over another but rather to survey and describe the various accounts that have been most popular. These debates will no doubt continue for decades and centuries to come, and the moral questions we’ve considered will continue to be central to our philosophical concerns.

For the Christian, there is actually much to be gleaned from each approach. Like the teleological accounts of moral theory, the Christian Scriptures are very concerned with the character and qualities of human beings. Jesus’s “Blessed are those” statements found in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:3–12) are a good example of this. At the same time, however, the Bible offers a clear set of commands and guidelines to life in both the Old and New Testaments, marking a clear correlation to deontological accounts of moral theory. And while Christians like Augustine insisted that goodness itself is grounded in God’s own nature, what we are obligated to do in certain circumstances may very well be a matter of divine volition. As such, philosophical discussions about moral theory have a clear connection to many of the same concerns addressed by the Christian faith.

1. Mark Timmons, Moral Theory, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 17.

2. John M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Christian Life (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2008), 91.

3. Aristotle, The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

4. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terrence Irwin, 2nd ed. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1999), 1107a.

5. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1105b.

6. Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness, 50th anniv. ed. (New York: Signet, 2014), 30.

7. James Rachels, The Elements of Moral Philosophy (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999), 84.

8. See Scott B. Rae, Moral Choices: An Introduction to Ethics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009). Just to clarify, in providing the rationale behind it, Rae is in no way endorsing this view.

9. Rae, Moral Choices, 70.

10. Rae, Moral Choices, 70.

11. Arthur F. Holmes, Ethics: Approaching Moral Decisions (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2007), 39–42.

12. Jeremy Bentham, A Comment on the Commentaries and A Fragment on Government, ed. J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart, The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham (London: Continuum, 1977), 393.

13. Jeremy Bentham, The Principles of Morals and Legislation (Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1988), 2.

14. John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), 184.

15. Rae, Moral Choices, 77.

16. Frame, Doctrine of the Christian Life, 101.

17. Rae, Moral Choices, 77.

18. Frame, Doctrine of the Christian Life, 102.

19. Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, trans. James W. Ellington (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993), 30.

20. Alister E. McGrath, A Scientific Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 2:57.

21. Robert M. Adams, The Virtue of Faith (New York: Oxford, 1987), 97 (emphasis in original).

22. Timmons, Moral Theory, 23–33.

23. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007); MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988).

24. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 2.

25. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 183.

26. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 49.

27. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 186.

28. MacIntyre, After Virtue, 191.

29. MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, 355.