3.1 Recollection

The concept of recollection and its Platonic relative anamnesis are truly at the intersection of psyche and mind, intended as either two separate entities or two aspects of the same thing. Recollecting is obviously connected to reconnecting, remembering and memorizing as we previously evidenced (Tomasi 2016). Furthermore, this activity is at the center of the discussion on “remembered wellness”, “faith factor” and “relaxation response” in a spiritual and religious sense (Benson 1997). In regard to the latter, Herbert Benson describes a fundamental nature of human beings as “wired for God” in connection to this process and at the base of the healing process. This position is validated by numerous studies, for instance, in the research by Levin (1994, 1996) in connection to general medical practice and Widerquist (1992) for nursing. The work by Louis Ritz at this intersection between psyche and mind is also the cornerstone of the Center for Spirituality and Health at the University of Florida, which notes that:

Of course, any discussion involving psyche and mind cannot avoid some inclusion of the parallel term ‘soul’. There are many publications discussing these aspects, for instance, Whatever Happened of the Soul? Scientific and Theological Portraits of Human Nature (Brown et al. 1998) or Did My Neurons Make Me Do It? Philosophical and Neurobiological Perspectives on Moral Responsibility and Free Will (Murphy and Brown 2007). The underlying hypothesis is that there are multiple connections between an empirical/dialectical observation of a ‘top down’ system which accounts for an increasingly complex structure, cellular and molecular, starting from the DNA, that does not specify itself, but ‘recollects’ the elements given/created by a ‘higher function’ which certainly resembles concepts like a ‘higher self’ or a ‘higher power’ with obvious implications for the philosophical debates on free will, determinism, materialism/reductionism and the mind-body problem. The focus however moves from experimental neuropsychological research on the implications of agenesis of the corpus callosum, and investigates the related neural functioning as underlying mechanism for higher cognitive processes in humans. The perspective here is truly monistic and materialistic, but certainly not reductionist, as it claims that the immortality of the soul cannot be (empirically) verified, but human beings were created by God with a form/shape in which every part of our body is the origin and creation of our self, and thus we are fully ‘embodied’, cognition and mind included. Of course, this perspective also does not diminish the belief in a creator God, as the expectation—also in an eschatological sense—is that God will recreate us after our physical death as a complete version of us, starting from the beginning, although concepts like space and time would obviously need to be rethought in connection with a divine being. This ‘re-embodiment’ has obviously a strong metaphysical basis, albeit it can also be viewed from a purely evolutionary biology perspective, or in connection with other forms of religious naturalism and even—as much as this terms sounds very paradoxical to some—computational-digital spiritual atheism (as in Eric Steinhart). Of course, this means that individual soul/mind and individual vs. universal spirit are fully part of our bodily features, and therefore cannot be separated in essence, as they are not—but they do represent—two different things. According to this view of course, this representation is simply “representing to the perception of the viewer”, who thereby examines such evidence. In the platonic interpretation, this has to do with the anamnesis at the basis of the theory of recollection. In other words, our emerging evidence is rooted in recollecting ideas our soul always possessed, but though the imprisonment of/by (although the latter would imply a purpose actor in/as) the body. The fundamental point at this level is not so much related to questions on existence of free will, the (immortal) soul or (a) god, but on a concept of ‘recollection’ based on such philosophical premises, as opposed to ‘recollection’ in psychological terms. More specifically, following the interpretation of Hegel by Verene, psychology observes reality, and objectifies it in terms of analyzing thoroughly, but without comprehending it in terms of its internal essence-being. The comparison here is between evidence-based observational science and ‘self-perceiving’ phenomenology. Continuing with this interpretation, this phenomenology expresses this act of recollecting in terms of consciousness being both inside the memory being recalled and outside it as the power of its recall. Therefore, and we have to be clear in this regard, our neural functions cannot be equated with our psychological functions; our brain cannot be the same as our mind. The reason is that it is the mind that actually operates the thoughts behind these lines, and it is actually the mind creating this comparison between itself and the brain, although the brain plays a fundamental role in modulating this activity. Verene even states that in attempting to “extract the mind from such inner process and manifestation and reestablishing it in the brain”, psychology becomes very similar to reductionist-materialistic—scientifically very misguided—approaches such as low-level physiognomy and phrenology. In the words of Verene, the concept of a “beautiful soul” is defined by being “its principle understandable to the self of the matter in hand” (Verene 1997).Spirituality deals with what we find eternal, beautiful, meaningful and just, and asks us to contemplate “what should be”. Science and technology deal much more with “what is” and how best to predict and manipulate it. The interface between these powerful forces is of immense and immediate importance because their interaction is likely to strongly influence how the next generations shape the future of our world. Careful analyses of our debates about healthcare, ecology, economics, politics, nationalism, educational policy and even law often reveal this underlying conflict between “faith” and “fact” based realities.1

Psychology puts, rightly so, a lot of emphasis on external behavioral processes, but in drawing parallels between these behaviors and their neural underpinnings, it fails to consider inner existence and essence. In this context, we have to mention the importance of the validation of inner existence and essence from the perspective of possible mechanistic explanations—that is, neural processes—and certain philosophical views. In particular, we are referring to the multitude of offspring studies originated in the Libet experiment (Libet et al. 1979) in connection to the existence of (or lack thereof) free will. To quickly summarize the main points evidenced by the results of this experiment, physiologist Benjamin Libet wanted to shed light on the connection, whether causal or not, between the conscious experience of volition and the so-called Bereitschaftspotential, usually translated as ‘readiness potential’ on the base of previous findings by Hans Helmut Kornhuber and Lüder Deecke (1990). In details, these researchers were able to demonstrate that a basic hand movement in the subject studied, between a certain initial nervous activity in the motor cortex of the subject and its actual execution by the subject, about one second elapses, although our human everyday experience is that the time between action and execution appears much shorter, so that we think that we did (i.e. decided to activate) the movement. In the Libet experiment the repeated results showed instead that the Bereitschaftspotential began about 0.35 seconds earlier than the subject’s reported conscious awareness that “now he or she feels the desire to make a movement” thus demonstrating that, in spite of appearance (= perception) humans have no free will in the initiation of (their) movements. This outcome has obviously a very strong impact on the very concept of recollection, since this concept involves time or, better said, an accurate (objective vs. subjective) perception of the passing of time, in which (a) decision of taking action precedes the action itself and (b) recollecting something is meaningful (true) only if this something happened/existed before the act of recollection. However, a problem arose from this experiment, that is, the fact that, if free will turned out to be an illusion given these premises, the same couldn’t be said for the ‘free won’t’. With the latter, what is usually intended is the ‘ability to do otherwise’ or the veto ‘power’ to prevent the actuation of action—in our case, the ability to prevent movement right before activating such movement, for example, ‘at the last moment’. The ‘ability to do otherwise’ requires a further analysis of the many steps in between and often opposite, and the many conflicting or pseudo-conflicting positions required in soft and hard determinism vs. indeterminism and possibilism vs. impossibilism. A criticism of the assumptions in the conceptualization of free will evidenced in the Libet experiment, more specifically on the controversial nature of the term, ‘free will’ is a core idea in the work by Peter van Inwagen, with particular regard to the comparison between compatibilism and incompatibilism. William Klemm (2010) instead posits that there are certain flaws, beyond conflicting data and outcome analysis, in the interpretation of similar experiments based on the fact that:

The analysis by Klemm covers a wide range of objections to this type of experiments aimed at establishing the existence or non-existence of free will from the perspective of neuroscience. Among the most important aspects of Klemm’s analysis we should evidence that both concepts of decision and conscious realization need to be reassessed in the context of evidence-based experimentation, more specifically understanding that the processes underlying decision-making are multiple and therefore (a) cannot be reduced to a single mental process to be analyzed, and (b) cannot be used as a basis (i.e. as an ontological-experimental justification) for ‘all mental life’. Furthermore, Klemm argues that there is a delay between the (conscious) realization/perception/awareness that a certain decision (which, in itself is not instantaneous) has been made and the actual decision made. Moreover, Klemm sees these two elements as representatives of two distinct processes. Klemm also recollects some concepts from classical philosophy and psychoanalysis including the subconscious mind, which, in his view, is behind certain decision-making processes and “cannot know ahead of time what to do” (Klemm 2010). From the perspective of memory and recollection, this could be certainly applied to procedural memory, responsible for the ‘know-how’ involved in multiple skills such as motor coordination (certainly in collaboration with other brain areas, including the cerebellum) and repetition or playing an instrument, and is a fundamental part of long-term memory.1) timing of when a free-will event occurred requires introspection, and other research shows that introspective estimates of event timing are not accurate, 2) simple finger movements may be performed without much conscious thought and certainly not representative of the conscious decisions and choices required in high-speed conversation or situations where the subconscious mind cannot know ahead of time what to do, and 3) the brain activity measures have been primitive and incomplete.2

As we have seen, different understandings of memory and recollection imply and influence different conceptualizations and categorization of mind and psyche. The direct outcome of these views is a very complex contemplation of what it means to ‘have’ free will, and whether this freedom is something ‘we’ can ‘possess’ at all. Using the framework shared at times or at least in part or in some areas by compatibilists and soft determinists, we could attempt to define stages, degrees or layers of such freedom and assume that there isn’t such a thing as one type of freedom or at least that “freedom is not free, at least not philosophically.” In other words, we would assume (possibly in conflict with Occam’s razor perspectives) that there are other contributors or effectors to the “levels of existence or action” of freedom in the context of ‘Will’,3 including time/history, consciousness/awareness and personal action. This perspective, shared in part also by Kornhuber and Deecke (2012) claims that there are ways an individual-subject can ‘increase’ the level of freedom through an improvement of the self (which we argue could bring us back to the cura animae) as opposed to self-mismanagement, which would lead to an incremental loss of degrees of such freedom. Obviously, this view is in many ways very similar to some religious perspectives, especially within the monotheistic traditions, on the concepts of ‘sin’ and ‘repentance’ involving an external source of judgment and activation, because we, as human beings part of and in this world cannot have ‘full’ free will, because this would entail a complete freedom from nature, which we are part of. Following this interpretation, we hereby mention the very interesting series of studies by Sartori and Defanti (2012) in regard to ‘our role’ in the definition and activation of the Bereitschaftspotential and the very ‘activation of existence’ of free will. The most important aspect of these studies is that we might actually be ‘responsible for our response’ in the sense that our belief in the existence of free will has the power to impact the readiness potential positively (with a decrease in time) or negatively (with an increase in time), by virtue of our judgment of this ‘positivity’ or ‘negativity’. In other words, the more we believe that free will exists, the more our readiness potential will increase in speed, in turn making/allowing us to have a more direct control over our decision making processes, and thus our actions.

As previously evidenced, if these studies primarily focused on free will, a similar perspective can certainly be applied to the ‘free won’t’, as in the research by the Berlin group led by John Dylan Haynes (2016) which suggested—those were the exact experimental results in the studies—that in a ‘speed-activation’ competition between human subjects and a Brain Computer Interface, the ‘point of no return’ for the ability of humans to veto an action was at 200 milliseconds before the movement. In this experiment, the computer was programmed to predict the human subjects’ movements in real-time, from observations of their Bereitschaftspotential evidence in EEG activity. The interesting factor was, however, that even passed this point of no return, thus when the pedal was already set in motion, the subjects in the study were able to reschedule their action by vetoing (i.e. not bringing to completion) the already (previously) started behavior/process/activation. These considerations achieve a status of a much higher activating capacity in the context of possible interactions between ‘subjective free will’ and ‘common-communal free will’. With these postulates, we want to stress the importance of a conceptualized awareness of action, even more of being, in relation to action and being at the community level. More specifically, we should better understand how our response to self and by self, in the context of ‘activation of existence’ and (self) identity comes to influence the level of freedom in choices of belonging to a group, a community or even a ‘cause’. In other words, what is the role of our sense of identity and our ability to make free and informed choices in the context of bigger societal decision making patterns? If our sense of self and sense of belonging to a family, a community, a religion, or a nation depends on these parameters, then we will understand that there are multiple layers of activating essence in the action of the single individual within the group, between group members, and at each intersection, especially on ethnic and racial levels. An interesting question in this context would be what are the possible implications of confounding-confusing terms such as race and ethnicity? Can we operate a ‘switch’? Can this ‘switch’ be turned on or off? From the perspective of memory, recall and recollection, the problem of self-identifying with and within a specific subgroup of people has a lot to do with cultural background, upbringing as well as psychological understanding of our cognitive processes, our emotions and the possible distortions involved. Although we could argue that it is ethically preferable, at least on a social-public level, to be ‘politically correct’ in preferring the term ethnicity over race in the public speech, as it moves the weight from biology to culture, this process only appears to solve the problem, while in fact it simply moves the issue one step further, and whether this comparative truly means ‘further up’ or ‘further down’ remains to be seen. In fact, we could argue that the main issue lies in the perception some might have of being either ‘inferior’ or ‘superior’ to other (sub)groups of people. This (mis)perception is from time to time justified using a multitude of scales and references systems—from the purely biological to the socioeconomic and historical—to defend the need for separation in the judgment of specific groups of people (Mujkanović 2016). The multidisciplinary approach of the study of diversity should help us understand how biology, sociology, anthropology, philosophy, psychology and economics are deeply intertwined in our attempt to understand how these premises influence our everyday interaction with each other. Simply changing the scale or references system won’t destroy the false assumptions and misconceptions underlying ethno-racial superiorities and inferiorities.

3.2 Talking to the Mind and Mind-Talking

3.2.1 Behavioral Neuroscience

This disciplines combines a variety of approaches provided by multiple areas of investigations, justifying the other names this specialty is known as, including—depending on geographical, political, and cultural areas the definitions might differ—psychobiology or biopsychology, psychophysiology or physiopsychology, comparative psychology and psychopharmacology, all the way to the inclusion of cognitive neuropsychology. As we mentioned elsewhere, the somewhat artificial separation between disciplines that are so deeply connected is in part related to cultural norms as well as artificially produced to satisfy economic needs, for instance, research grant funding or specific scientific/academic needs. Analyzing behavior, especially human behavior, is as fascinating as complex and complicated. Throughout the history of social and ‘hard’ sciences, there have been an enormous amount of theories, trials, experiments, suggestions, ideas, qualitative and quantitative data and interpretations supported and/or challenged by at least as many philosophical positions. In behavioral neuroscience, the divide between mind and body appears to bear the weight of all these approaches, their difficulties and obstacles, and all the passionate ways in which proponents of monistic and dualistic, perspectives—including the now classical Cartesian duality on one side, and physicalism, idealism and neutral monism on the other—as well as every other position in-between or beyond the ‘standard’ viewpoints, have been carried on in the pursuit of an ultimate truth of the origin, scope and function of (human) behavior.

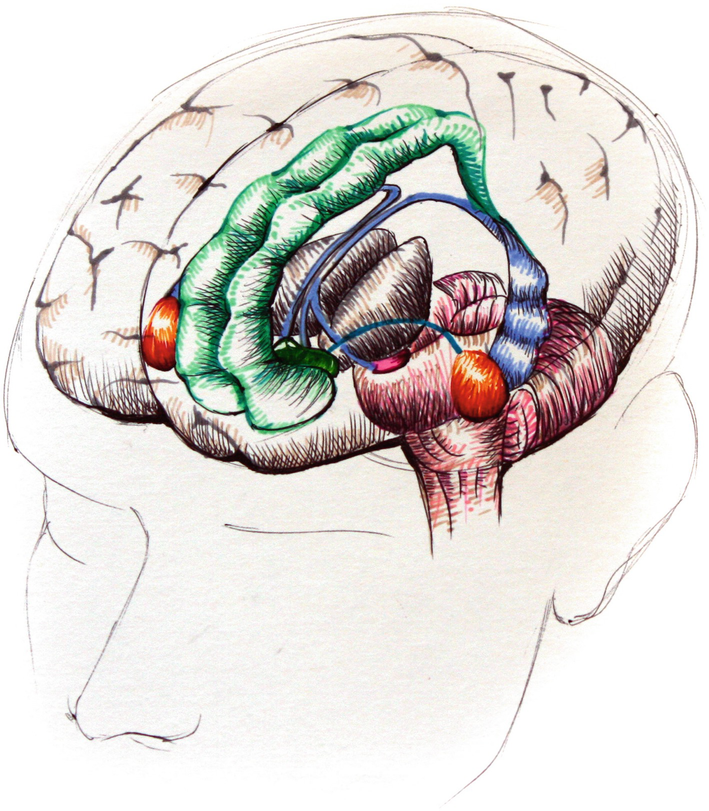

Left superior frontolateral view of the cerebrum with the limbic system with cingulate gyrus (green), hippocampus (blue), amygdaloid bodies (red), mammillary bodies (fuchsia), thalamic areas (brown), pineal gland (light orange), and brain stem (pink)

Among the major schools of psychological thought, we find a purely biological point of view—to some extent originating in Platonic perspectives—as well as the cognitive, social or socio-cognitive, existential and humanist(ic), psychoanalytical and, of course, the purely behavioral and functional(ist-ic). Behaviorism and functionalism have played a very special role in connection to behavioral neuroscience especially in relation—more often juxtaposition or absolute opposition—to type physicalism, itself variously defined as identity theory of mind/type identity theory but also (dualistic) mind–brain identity theory or, alternatively—especially in a philosophical sense—reductive materialism within philosophy of mind. Of course, in the case of behaviorism, “the assumption is that behavior is what is learned, whereas in cognitivism the assumption is that behavior is the outcome of what is learned “(Stevenson 1983). While behavioral neuroscience does not espouse any specific perspective, it is clear that the major theoretical contributions come from functionalistic approaches (especially in the concept of neural underpinnings of behavior) such as analytic, homuncular, machine-state, mechanistic, and psycho functionalism. In this sense, there are types of mental/psychological events in connection/correlation to types of neural/physical events. Of course, the causal element is the main point of discussion, debate, and disagreement in this context. It presents some very complex theoretical issues, in part linked to other diatribes such as the divide between psychology of traits and social cognitivism. Of course, the main behaviorist point of view states that human behavior is a result of environmental or personal stimuli, including classical and operant conditioning and therefore assigning to stimulus-response learning processes on one side, and reinforcement, reward, punishment on the other, a constituting value to our thoughts and actions. In the case of functionalism instead, the claim is that everything—that is, our behavior, but also our (system of) beliefs, our wishes and desires, our intention and will—mainly depends on the related function connecting sensory inputs and behavior. Aside from specific theories, it is important to mention that, from the perspective of behavioral neuroscience and the comparative ‘nature vs. nurture’ the social-cognitive theory triad ‘personal-behavioral-environmental’ offered by Bandura offers good material for discussion. In any case, the investigation on the legitimacy and clinical application of these models rely on the conceptualization of parallel concepts such as the self, the ‘I’ and the person(hood). To use a psychoanalytic framework, we would for instance set ‘I’-focused psychoanalysis against Object relations theory. In the first case we encounter the theories by Freud, Hartmann, Rapaport, Spitz, Mahler, and Erikson; in the second case the most important representatives are Fairbarn, Klein, Bion, Winnicott, Guntrip, Stuart, Bowlby and, of course, Ferenczi. Jung and especially Rank have been in some instances presenting a very useful link between these two approaches.

Of course, theories of behavior need to find their evidence-based counterpart in direct and/or laboratory experimental observation. Scientific improvements happen in this context thanks to the continuing efforts of researchers, as well as fortunate events (as in ‘lucky’, at least for the scientists involved, not necessarily for the subjects-patients) representing a scientific ‘jump’ in advancement toward understanding, as in the case of Phineas Gage. Other examples are offered by the research conducted by Gazzaniga on corpus callosotomy or the studies by Penfield and Rasmussen on epilepsy. In the case of (artificial-surgical) separation of right and left hemispheres, however, the common view generally sees the left side as ‘better’ (for instance) at mathematical-logical-analytical processes, but also writing and reading. The right side of the brain instead is ‘better’ at identifying patterns, schemata and ‘seeing the bigger picture’. From the perspective of behavioral neuroscience, we can certainly see how this division is symptomatic (in a theoretical sense) of a partial function, even more a partial understanding of reality. Given this premise, we need to reassess terms such as ‘magical thinking’, which are often viewed, especially within psychiatry, as indicators or even ‘traits’ of delusional content, as the subject-patient ‘connects dots that are either not connected, or connected in a very different way, or even not existing at all’. While this is true in many cases of mania, hypomania, paranoia and psychosis, we believe we should pay more attention to phenomena that we ‘perceive as connected’ and turn out to be indicator of a bigger picture. Of course, delusions are still true in the aforementioned clinical cases, but we argue that there are different stages, layers or even levels of perception; on/in some levels connection is only apparent (thus absolutely absent) but in others a deeper connection might be present (read: real, true) but not evident using either our common senses (minus, we could argue the so-called sixth/seventh sense or the sensus divinitatis) or the ‘classical’ scientific method. In fact, and we mentioned this aspect many times in this work, we should not confuse scientific (in the commons sense) evidence with all evidence, or scientific non-evidence with all non-evidence. In other words, we should be even more ‘scientific’ when assessing the results of, for example, a research study. If the study does not show results, that is (in this case), any connection or correlation, it simply means this. It means that ‘the study did not find/yield any connection or correlation’, it doesn’t mean (e.g. it doesn’t logically follow that) ‘there aren’t any connection or correlation at all’. In relation to this observation, and in connection to other neuroanatomical areas, we could think that perhaps what we can experience with (for instance) the prefrontal cortex is only a very limited part of reality, which has only to do with our rationalization of things. Maybe spiritual events can be perceived with the parietal/temporal lobe, etc. As with every study involving behavioral neuroscience, the conditio sine qua non for this type of investigation, is that experiments always contain at least one biological variable, either dependent or independent. As these parameters are used to link biological changes on the nervous system, more specifically on the brain, and behavioral changes, many experiments in behavioral neuroscience involve naturally—that is, as a result of natural biological development vs. decay or accidents, illnesses, diseases and disorders4—or artificially (man-made/developed) caused lesions. These include chemical, electrolytic, and surgical lesions (in a clinical setting, some examples are neurotoxins, surgery, and electric shock) and can be temporary, time-dependent, or even permanent (in the case of naturally occurring events). Of course, in all these cases, the theoretical framework linking multiple animal models to humans plays a critical and controversial role in the study of mental health disorders, especially in the research behavioral neuroscience shares with abnormal psychology. This means that this discipline can offer great insight to the treatment of disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease, Huntington’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. In the case of more complex (not necessarily in a purely medical sense, but given the complexity of psychoneurological and social components involved) disorders such a Major Anxiety Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder, the direct causal effect of neurological areas, functions, structures and processes appears to be in need of further exploration and understanding. Again, this can happen via technologies previously discussed, such as brain imaging (MRI, fMRI, EEG, PET, SPECT, CAT/CT, MEG, etc.), manipulation (including inhibition5 and psychopharmacological interventions6), and stimulation (as in TMS), as well as via measuring methods like electrode-based monitoring (single-unit or multi-electrode recordings), sensitive dye-based optical techniques (examples include voltage-sensitive dyes and voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins that have been genetically encoded), as well as functional neuroanatomy and genetic (sequential) mapping or engineering. To be sure, at the center of the aforementioned mental health disorders there are areas of ‘perceptual disconnect’ with reality, either in a form of cognitive distortions such as rumination, jumping to conclusions, all-or-nothing thinking and negative self-talk, or due to neurologically-based disruptive feature to communicative and spatial-relational abilities. These parameters are even more defined by the very way we observe the normal functioning of psychological qualities in such context and the causal or mechanistic process inference we use to justify our psychological observation. From a philosophical perspective, the stage of ‘Observational Reason’ in the analysis of Verene of Hegel’s Phenomenology, as well as Lavater’s physiognomy and Gall’s phrenology do not merely represent a mistake in scientific analysis, but constitute a preliminary stage which will eventually lead to observational psychology and the analysis of mind processes. This process is however made increasingly complex by the environmental (in the philosopher’s words a true milieu) component, both inner and outer, experienced by the individual-subject/subjected individual. To be more specific there is a reflection of the inner into the other/outer. In fact, Verene goes as far as demanding—and this request is to be found in times that predate the very beginnings of both psychology and neuroscience, as in Hegel’s phenomenology—a so-called technology of behavior beyond both behavioral psychology and neuroscience, in which behavior is not merely causally connected to states of mind, feelings, traits of character, human nature or “faculties, inclinations, and passions” (Verene 1997). That is exactly the problem with some behaviorist perspectives in psychology and neuroscience, that is, the forced “flattening of the inner and the outer”, which were already denounced by Hegel with regard to physiognomy (Tomasi 2016). At the core of this problem is the false assumption, which is truly a ‘presumption without presentiment’ that our current scientific method is able, when aptly and thoroughly applied, to investigate the ultimate reality of things, whether conscious or unconscious, and whether conscious or unconscious actually exist.

3.2.2 Affective Neuroscience

Similarly to what we have said in regard to behavioral neuroscience, with affective neuroscience we generally indicate the analysis of neural mechanisms as they underlie processes of emotion. More specifically, feelings, moods, emotions and aspects of personality are examined both using a neuroanatomical approach as well as by investigating psychological theories of personality. The contemporary debate about the function of neuroscience to study emotions has moved from ‘Descartes’ Error’ as evidenced by Antonio Damasio to a more omnicomprehensive theory of emotions which links their production, activity and effect on the neurological aspects of human nature, thus not separated from high(er) cognitive functions. Before Damasio, important contributions to this research have come from Paul Broca, James Papez, Paul D. MacLean and were subsequently developed by the studies on empathy and the discovery of mirror neurons by Giacomo Rizzolatti, Giuseppe Di Pellegrino, Luciano Fadiga, Leonardo Fogassi, and Vittorio Gallese, as well as by Jaak Panksepp, who actually coined the term ‘affective neuroscience’.

Lateral view of the brain with cerebrum (beige/white) and cerebellum (maroon), with highlighted neural areas involved in emotional processing according to Pessoa (2008): somatosensory cortex, anterior insular cortex and anterior temporal lobe (blue), and orbitofrontal cortex (red, used most frequently)

This analysis would serve a better definition of a ‘mental state’, not only from the psychiatric point of view, but also according to constructionist approaches within psychology. In this sense, an entire system of multiple elements—which might be in turn considered as systems themselves—work in cooperation/combination (thus eliciting patterns of neural activation) to produce specific emotions. Of course, there is an immediate need of defining what the ‘3 B’ or ‘basic building blocks’ would be on a neuroanatomical level (i.e. the brain areas and structures involved) and on a phenomenological/ontological level of definition. An example of the latter might be the seven universal facial representations/expressions of (human) emotions of anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, contempt and happiness developed by Paul Ekman starting from a Darwinian research viewpoint, and further expanded into the emotions non-necessarily encoded in (universal) facial muscles: amusement, contempt, contentment, embarrassment, excitement, guilt, pride in achievement, relief, satisfaction, sensory pleasure and shame. Of course, the investigation in this sense focuses on the construction of mental states on different levels. First, on the level of bio-physical/mechanical functions and processes (facial expressions in particular, but also body-related metalanguage such as posture, micro/macro movements, all the way to possible psychomotor activation and/or agitation). Second, on the level of neural networks and patterns, to account for specific psychological elements such as attention, cognition, computation, memory and perception. Third, on the level of the internal-external connection between the above and the production, process and communication/delivery of emotions. Starting from the hypothesis that more basic structures and functions account for (which is again, not the same as ‘create’ or ‘produce’) multiple, interconnected and distributed patterns of neurological-psychological (also only a correlation, at this level) activation, we thereby infer that an ‘affect’ originates from structurally ‘inferior’ components, with the production of an emotion as the last part of the chain connecting the individual to others and to himself/herself. Another point of view challenges this assumption, defining the previously discussed emotions as basic, not only psychologically but also in a biological sense. This approach is referred to as locationist because of the perspective in which a ‘single emotional category’ contains multiple mental states and relates to either a single brain area or multiple neural networks, but always distinct, although subjectively experienced. Another approach takes another route and views the connection vs. separation within a mutual activation of the right vs. brain hemisphere.

More specifically, the right hemisphere hypothesis identifies in the right hemisphere the neocortical structures and subcortical systems of attention and autonomic arousal underlying (human) emotions, more specifically the expression, and perception of synthetic/symbolic, whole-holistic-integrative (the so-called big picture), image-related, nonverbal, pictorial mental frameworks and interpretations of reality. Another point of view, the valence hypothesis, distinguishes between the activities of the right hemisphere as processing center for negative emotions and the activities of the left hemisphere as processing center for positive emotions, although there are many ‘moderate’ positions according to which the two hemispheres are not fully ‘compartmentalized’, ‘specialized’ or ‘lateralized’, but present combined, communicative features in which certain aspects are more dominant in one hemisphere than in the other. Of course, aside from the evidence-based data collected through the previously discussed scientific methods and technologies, there is a certain level of cultural influence into dividing the brain into a more emotional-creative right hemisphere and a more analytical-logical left hemisphere. While it is true that aspects such as symbolic representation, imagination, intuition, visual-spatial representation, musical perception and/or appreciation, and ‘whole picture-insight’ have been connected to the right hemisphere, and language understanding/speech production, analytical-logical cognitive processes and reasoning to the left hemisphere with the support of qualitative and quantitative studies reporting on functional activity and underlying processes, a complete lateralization in which only one side does only one thing appears to be somewhat misleading and incomplete. Of course, the same can and should be said about the differentiation in terms of neural structures and functional activity from the perspective of sexual/gender characteristics. From the perspective of affective neuroscience, one of the hypothesis tested in this context, is whether female brains, or brains usually associated with female traits appear to promote a more emotional-empathic behavior as opposed to male brains. Again, sociocultural upbringing, expectations and stereotypes might play a very big role in defining what it means to be a woman or a man in the first place. What the scientific method can provide is the analysis of those brain areas that have been associated (again, underpinning/underlying behavior in connection to neural functions) with certain traits. In this sense, most of the current research has focused on chemistry and structural anatomy, and taken into account specific functions of neural areas. In the first case, among the most relevant examples we find studies on the effects of estrogen and oxytocin on female subjects and testosterone and vasopressin in male subjects. In the second case, the relationship between nervous and endocrine system is especially meaningful to account for differences in functionality and transmission.

From the broader perspective of affective neuroscience however, the vast majority of studies available to the scientific community have so far dealt with specific brain areas such as the amygdalae, the cingulate gyrus, the fornix, the mammillary body, the olfactory bulb, the thalamus and the hypothalamus, the hippocampus (all parts of the limbic system), as well as the basal ganglia, the cerebellum, the insula, the orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortices, and the ventral striatum. Of course, these areas are observed with specific experimental studies (read: hypothesis testing according to the principle of falsifiability) aimed at quantifying affection in connection to aspects such as cognition and emotion, and are therefore overlapping with behavioral and cognitive neuroscience. Combined research and meta-analyses aside, at the very center of this type of studies we find processes like inhibition, modulation, (social-interpersonal) response—especially to ‘go and no-go’ cues—and psychophysical response to internal-external stimuli of differentiated types. In this regard we should also mention the importance of social constructs in connection with semantic production, especially from the viewpoint of developmental psycholinguistics, as particular responses might be elicited by specific words or combinatory set of words, within specific culture, and familial, ethic, religious, and/or social upbringing and background. From this perspective, finally, of great importance is scientific testing to categorize memory and attentional bias (measured for instance with emotional stroop task) in connection with the (again, relative/interpersonal vs./subjectively perceived) moral-ethical value, weight and valence of negative and positive words on affect. Other very valuable tests used at the intersection of affective and cognitive neuroscience are the Fear-potentiated startle (FPS) and Dot-probe paradigm, with foci on fear conditioning in the first case, and selective attention in the latter.

3.2.3 Neuroethology

- 1.

How can an (animal) organism detect stimuli?

- 2.

How can the nervous system of an (animal) organism perceive and represent external/environmental stimuli?

- 3.

What are the processes in the nervous system allowing acquisition, storage and retrieval/recall of information about a stimulus?

- 4.

How do neural networks encode behavioral patterns?

- 5.

What are the processes of behavioral coordination and control in the nervous system?

- 6.

What are the premises of the ontogenetic development of behavior in relation to the processes, systems and mechanisms of the nervous system?

As Neuroethology shares many elements with classical neuroscience, neurobiology and evolutionary biology, psychology and zoology, it is not surprising that the history of Neuroethology overlaps with the history of these disciplines. The philosophical attitude toward the systemic combination vs. division between human and non-human animals has changed many times in history, but we can say that a truly scientific method in the modern, evidence-based sense of the term has been applied to ethology only in the twentieth century, and as such it has allowed ethology first, and neuroethology after, to be considered separate fields from natural science—at least the classic version of this field, traditionally descriptive in nature—and ecology, albeit still part of zoology. The main contributors to this process were Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, Karl von Frisch, Erich von Holst, Theodore Bullock, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Edgar Adrian, Charles Sherrington, as well as Robert Capranica, Jörg-Peter Ewert, Walter Heiligenberg, Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley and Masakazu Konishi. Although the connection between field research and studies in laboratory setting has been investigated throughout the history of Neuroethology, it is evident how some of the techniques used in this field are limited to the latter, also due to the very structure of such experiments and the standards, in terms of observation, control, accuracy and falsifiability, they need to follow. This represents both a challenge (for instance, the validity and relevance of findings in natural habitat) and a strength (experimental design allowing for the development of new techniques and technologies useful to replicate natural-istic environment and mimic behavioral aspects) of modern neuroethology. Given these premises, among the most important foci of investigation in neuroethology, we find a broad investigation on the contributions of neurons, hormones and genes to animal behavior, comparative, cognitive and computational aspects of function, including higher processing centers, visual/spatial memory collection, production, storage and recollection, activity levels in sensory systems, eye and head movement, signaling plasticity and behavioral neuronal complexity, learning processes and skill development (although there is certainly a somewhat anthropocentric bias in this very definition, for instance, in relation to the production and execution of sounds/songs).

3.2.4 Neuropsychology and Neuropsychotherapy

Many scholars view psychotherapy as an applied form of psychology, more specifically involving the application of psychological theories and research to provide therapeutic support to mental health patients. Certainly, this is a very limiting and narrowing definition, but it helps us identify some basic concepts upon which to relate the term ‘neuro’. In fact, if psychology is said to be the study of the mind—leaving aside the mind/brain problem and the discussion on the existence of a/the soul for now—and thus constituting both a scientific field (whether ‘social’ and/or ‘soft’ science as descriptors make sense at all, we will discuss later) as well as an academic discipline, psychotherapy by definition focuses on the θεραπεία and is therefore a form of service, care, treatment and/or healing method and technique. Certainly, as such, the scope of psychotherapy is very close to the one of psychiatry and we should ask whether being, at least theoretically but with clear legal and social outcomes, separated from the field practice by the ἰατρός is actually appropriate in this setting. In this regard, the ongoing debate on the inclusion of mental health in the general medical field under the branch of psychiatry is of fundamental importance from a philosophical point of view. We will further analyze this debate, for now we will just refer to the work by Thomas Szasz in connection to the antipsychiatry movement, George Graham’s irrationality model, the Tidal model, Peter Sedgwick’s social construct/value judgment model as well as other philosophical approaches including the perspectives of Paul Feyerabend and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

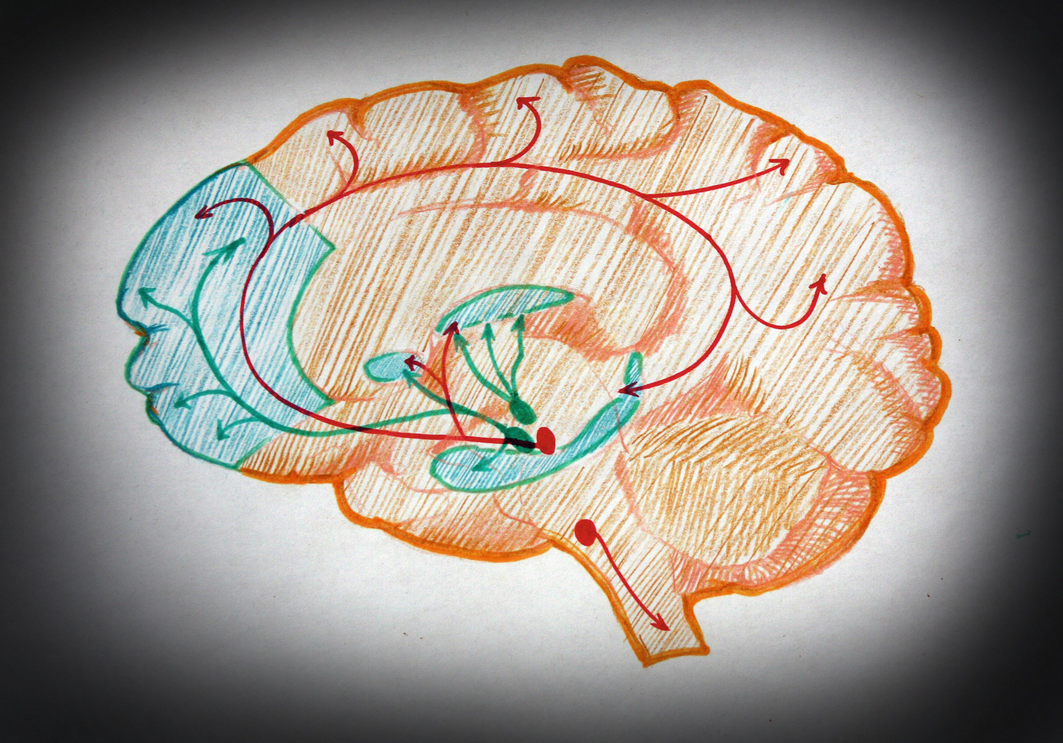

Left lateral midsagittal section of the brain with serotonin pathways (red) and dopamine pathways (green). The two red dots represent the Raphe nuclei, and the two blue dots indicate the ventral tegmental area, while the aquamarine-highlighted areas indicate frontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, striatum and hippocampus

To clarify, neuropsychotherapy provides support-solution to problems of discordance/disconnect by focusing on the very interface between mental processes and their neurological counterparts from a therapeutic perspective. According to Grawe (2004), therapeutic success happens through the appropriate Bedürfnisbefriedigung (roughly translated as ‘satisfaction of needs’ even beyond Maslowian viewpoint) of orientation/control, pleasure/avoidance, attachment, self-elevation/protection, as a preventive-protective mechanism for the possible development of mental health disorders, which are in turn the product of failed Konsistenzregulation or consistency regulation. Following Grawe’s consistency theory (1998, 2004), the (human) organism strives from a form of union-unity-integrity defined as Übereinstimmung or Vereinbarkeit, thus referring to conformity and compatibility of the concurrent neural and psychological processes. The higher the levels of conformity and compatibility, the healthier—in a thereby addressed connection between body and mind—the organism (itself a combination of the two). Thus, neuropsychotherapy fosters a better patient-provider relationship, which in turn focuses on using the explicit function mode of the brain to induce implicit changes by enabling/empowering the patient to raise awareness of her/his perceptions and achieve her/his motivational goals. From a neurological perspective, strong motivational activity via concrete positive life experiences produces healthier structures and processes in the brain, starting from the activation of the dopamine system. In this sense, the clinician becomes (as it was in the traditional-historical sense) a mentor, guide, teacher and role model for the patient. The therapist thus promotes healthy decisions by working on the “[I] want/ [I] will” parameters of the patient, given that (a) people learn things they want to learn more easily and (b) the conscious goal is not top of the neurological hierarchy, but is dominated by higher-settled, unconscious (implicit) goals. Therefore, if people make a conscious (explicit) decision, this has already fallen implicitly (Growe 2004).

In the NPT panorama by Rossouw (2014), neuropsychotherapy starts from the neuroscientific investigation on environment, biology, chemistry and psychology to focus on cognitive and functional re/habilitation, neuropsychoanalysis, neuro-behavioral psychotherapy, therapeutic assessment, and affective reconsolidation approaches. More specifically, neuropsychotherapy combines/incorporates psychodynamic, Gestalt, and cognitive approaches where “Each psychological treatment program has components of empathy, supporting, understanding, observation of difficulties, integrity, learning, and a basic understanding of the effects of placebo, etc.” (Roussow 2014). In this combination of multiple theoretical perspectives and diverse psychological schools of thought, we need to be reminded of the very specific orientations of humanistic and positive psychology. In the case of a humanistic approach, philosophical traditions close to phenomenology, hermeneutics, constructivism, postmodernism, transpersonalism, existentialism and phenomenology—Camus, Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, in particular—serve as psychological basis (which is assumption) for the debate and follow a more qualitative and individual, singular, subjective-based approach in research (Waterman 2013). In the case of positive psychology instead, the traditions go further back in the philosophical tradition, even tradition with a ‘bigger “T”’. Certainly, in humanistic psychology we also find some references to (a)theological debate, and even hermeneutics, but it is in the positive approach that we truly find the Classical tradition of Aristotle and the Hellenic, eudaemonist background, as well as an empirical, pragmatic and quantitative methodology using sample size research samples and focusing on well-being strategies, motivational interviewing, empowerment, exercises and action-taking (Tomasi 2016). Positive psychology also means finding ground for debate in Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Tillich, the medieval tradition of Christian philosophers, as well as Stuart Mill (more in detail, the inductive approach and the five methods), Russell, Popper and Fromm (Waterman 2013). A possible combination of humanistic and positive approaches is welcomed in the context of ‘identity as self-discovery’, which is at the center of Waterman’s eudaimonic identity theory (2013). In the context of neuroscience and psychology applied to therapy there are constant ‘cognitive swings’ between the principle of (medical-clinical) contiguity and contingency, which are the product of behavioristic frameworks, including measurable outcomes and continuous progressive testing, as part of predictability and falsifiability. Neuroscience benefits even more from cognitivism especially due to the further developments of situated cognition (Engeström and Middleton 1996). In neuroscience, this results in a much more attentive analysis of processes such as information and memory processing, including Short-, Mid-, and Long-Term Memory (Long Term Potentiation process based on neuronal synchronicity) demyelination-based effectors on procedural developments. Moreover, if this cognitive approach can shed even more light on phenomena such as confabulation and source misattribution, metacognition is in itself a cognitive form of self-perception. This self-perception can indeed be understood under the framework of the Greco-Roman heritage, in particular Socratic humanism. However, we could certainly argue that the primacy of self in the context of self-discovery has morphed multiple times in history, with often contradictory outcomes. The concept of γνῶθι σεαυτόν has moved from an oracular Delphic tradition with promethean components to the empowered centeredness of the human self in the Renaissance and finally to the “cogito ergo sum” of Cartesius and the critical reactions of Gassendi, Kierkegaard, Lichtenberg, Sanders Peirce, Macmurray and Williams, including the “sum, ergo cogito” by Monte, Hendricks, and others, fundamentally based on Nietzschean offsprings. This perspective also opens the door to translated interpretation to philosophically/cognitively interpret reality and our perception of it and our role in it through art, myth, poetry, rhetoric and eloquence following the models of Cicero, Quintilian, Socrates, Pico della Mirandola and Giambattista Vico. Furthermore, these philosophical methods are part of the debate on valuable self-knowledge strategies which include rhetoric and poetry exactly as part of a ‘form of memory’, also in the work by Verene (1997), as possible guidance for human activities, in a phronetic sense. Gadamer (1993) also relates to this viewpoint, in the sense that these human actions, behaviors, cognitions and decisions are through a comparison between an equilibrium brought to us humans by nature, passive in nature, and controlled, monitored by nature, versus an opposite equilibrium, entirely depending on our actions, and thus linked to the moment(-um) of human choice. This means that when the wholeness of man-nature-reality-existence is broken, diseases, psychological or physical, appear. Neuropsychology and neuropsychotherapy have to embrace also these perspectives to be effective. In other words, when we feel either overwhelmed or underwhelmed, we are stressed because of the (perceived or objectively actual) increasing number of chores, tasks, stimuli and stressors we face or because we lack enough ‘things to do or be stimulated by’ and we literally ‘lose track of perspective, of pattern, of purpose’. This brings us to the exact etymology of the Italian noia or the French ennui, which represent the negative aspects of the taedium vitae, a true ‘esse in odio’ which brings boredom to a threat. Given these premises, we can certainly understand how psycho-physical health is the opposite of disease versus continuum, and how maintaining balance and homoeostatic tension means comprehending whole/full identity as opposed to split/divided/dissociated identity, particularly in psychiatric-psychological terms, via diagnosis and psychotherapy focused on grief and loss. That is why psycho-physical health and lack thereof are truly philosophical concepts, as in the Latin bonus/bonulus/bellus and the Greek καλὸς, to define health as a (phenomenologically understood) phenomenon, an epiphany, possibly even a manifestation or teophany as we will see in Chaps. 5 and 6, related to Erfahrung and Erlebnis, in connection to human suffering, meaning, healing process and the existence of absolute parameters.

3.2.5 Ethnopsychology and Psychological Anthropology

The debate ‘nurture versus nature’ has been at the center of philosophical and psychological research since the very beginnings of these disciplines, and the interwoven, interdisciplinary fields of ethnopsychology and psychological anthropology (the latter term coined by Francis Hsu as a change to ‘culture and personality’) appear to be well equipped to try to address the questions arising from this debate. In attempting to understand human beings, especially in relation to other animals and the environment, the notion of culture and ethnicity plays a fundamental role. In fact, whenever we try to assign specific values and principles from an investigative or therapeutic standpoint, we are faced with questions of validity, universality and applicability of such concepts. Furthermore, this type of investigation truly challenges broader assumptions such as evolution/devolution/involution, identity, as well as time, history and space. Anthropocentric and ethnocentric views have been challenging foundations of ethnopsychology and psychological anthropology in the early stages of ethno-folk psychology with Wundt’s attempt to determine the cognitive abilities in a cross-cultural sense,8 as well as in (Freudian) psychoanalytic anthropology and have developed thanks to the work of Piero Coppo (ethnopsychiatry), George Devereux (cross-cultural research on mental illness), Erik Erikson (culture, ethnicity, identity), Jakob Friedrich Fries and Gottlob Schulze (psychic/mental anthropology), Erich Fromm and Géza Róheim (philosophical approach and field studies), Abram Kardiner (mental health vs. illness in ethnic minorities), Gananath Obeyesekere (psychological conflicts from the perspective of ethnicity and culture), Melford Spiro (psychoanalytic concepts as well as investigation of socio-cultural symbols and institutions as defense mechanisms), John and Beatrice Whiting (authors of ‘the Six Cultures Study’), as well as the series of research studies from psychoanalytic/psychological and psycho-anthropological perspectives by Vincent Crapanzano, Cora DuBois, Gilbert Herdt, Douglas Hollan, Viktor Frankl, Geoffrey Gorer, Carl Gustav Jung, Clyde Kluckhohn, Robert LeVine, Carl Rogers all the way to the anthropological research by Franz Boas and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Of course, the anthropological focus is toward ethnic, historical, social and evolutionary aspects, while the psychological focus covered transcultural (often acultural) and transnatural (but not non-natural, especially from the perspective of neurological underpinnings) elements of behavior, cognition and emotion.

Although often separated in academic setting (we will follow this trend by expanding the discussion in the section Cultural, Cross-cultural, and Trans-cultural Psychiatry ), the field of ethnopsychiatry is also deeply connected to ethnopsychology and psychological anthropology. In this context we need to mention the work by the Italian neurologist and psychiatrist Franco Basaglia; the French psychiatrist and neurologist Henri Collomb; Roberto Beneduce, an Italian Professor of Cultural Anthropology, and Medical and Psychological Anthropology; Győrgy Dobó, a French-Hungarian (with German-Jewish and in part Romanian heritage) ethnologist and psychoanalyst; and Frantz Omar Fanon, a writer, theorist, philosopher, psychiatrist, and political activist with a very interesting heritage (a descendant of enslaved Africans and indentured Indians on his father’s side and of black Martinician and white Alsatian descent on his mother’s) and a passion for the connection between culture, ethnicity, psychology and politics. Fanon wrote seminal works in this field, including Black Skin, White Masks (1952), A Dying Colonialism (1959), and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), the latter with a foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre. From the perspective of ethnopsychology and psychological anthropology, these researchers played a fundamental role in better understanding and possibly defining personality in terms of the characters vs. characteristics shaping and shaped by one’s culture, ethnicity, social/familial environment (including expectations, rules, regulations and norms) and biologically-based elements. In this analysis we find multiple approaches, including the basic-modal personality approach by John and Beatrice Whiting and Cora DuBois, the configurationalist approach by Ruth Benedict, A. Irving Hallowell and Margaret Mead, the National character sociological analysis by Alex Inkeles and Clyde Kluckhohn and the cognitive-anthropological approach by Roy D’Andrade, Ward Goodenough, A. Kimball Romney and Anthony Wallace. The definition of ‘culture as personality’ belongs to the configurationalist viewpoint, in the sense that each experience is absorbed and combined through the morphing, shaping, translating and transmitting activity of the symbolic structure. However, this very activity can be analyzed and thus interpreted with a cognitive approach as well, especially in relation to the networks of neural connections.

3.2.6 Neurotheology and Psychology of Religion

An important distinction needs to be made whenever we talk about the relation between religion, theology and any form of science, whether ‘soft’ or ‘hard’, in the modern conception of the term. First of all we have to relate to possible double hermeneutics (Giddens 1987) and the very conceptualization of the field and the practice. Conceptualization is under this analysis also translation and transfer, conversion, application and adaptation, perhaps even condensation via the use of a scientific method and methodology to something which can hardly be defined and/or possibly comprehended and understood through the same mechanism or conceptual-neurological framework of either neurology/neuroscience or psychology/psychological science. In this regard I would certainly refer to Plantinga’s ‘Warrant’ (Plantinga 2011, 2015) to better frame the problem. In the case of psychology of religion, we are faced with the application of these methods and conceptual frames of interpretation to spirituality and religion, their traditions, practices and epiphenomena as well as to the people related to the above, whether because of their practice or lack thereof, and whether the former and the latter can be quantified in terms of awareness of choice, a (free, free-will-based or lacking, ontologically non-existing, opposite to) choice between belief and disbelief; between creed, credence, faith and faithfulness; between atheism, theism, deism, agnosticism, defense, apologetics, theodicy and many more aspects and perspectives, attitudes and actions. Certainly, given the psychological nature of this discipline, the focus here is on psychological processes, as opposite to social practices and organizational forms studied by sociology or religion, and neural correlates investigated by neurotheology. In any case, both the legitimacy (in a strictly logical sense) and the validity of such attempts need to be very well analyzed before they can be fully understood to be appropriate or not for this type of investigation. In neurotheology, the task is trying to show the correlation between spiritual or religious experiences, starting from an individual level but possibly accounting for interpersonal and social levels as well, via neural structures, brain areas and processes such as the activity of mirror neurons, limbic system and cortical/subcortical structures, and the activity of the brain. This approach has received a lot of criticism from many proponents of both the psychological and the sociological investigation of religion, as the claim of a causal relation between the two (perhaps many more) sides of the spectrum, that is, spiritual-religious experience and neural correlates, appears to be not very well grounded in observational, evidence-based or theoretical-analytical terms. Of course, the same can be said about certain aspects of psychology, for example, the very concept of ‘projection’ (Tononi 2012). Although the term ‘neuroscience’ has been used in multiple contexts and with very different meanings and possible interpretations, the word has been first used by Huxley and made popular in both (popular as well as academic) philosophical-theological and (neuro)scientific areas by authors such as Drewermann, Hardy, McKinney and Newberg. Again, the focus of these works is on the connection between what can be experienced in terms of internal, interior, inner perception and the biological observation of specific mechanism of action preceding, following or happening at the same time. Another problem here is whether a conceptualization of time in chronological sense would make sense, but given the laboratory-based requirements for this type of studies, we will have to deal with the theoretical consequences of such approach. The application of psychometrics encounters the same level of problematic questions, as it requires—aside from the specific theories, technologies and/or techniques of psychological measurement chosen for a certain test or analysis—a level of value judgment or even belief in the quality vs. quantity of specific certain steps or increments, and whether the separation and/or distance between these has to be previously (a priori?) determined for the satisfactory (again, possible confirmation bias or methodologically flaw included) observation and follow-up analysis to take place. To be sure, here we are not trying to raise the level of skepticism toward any possibility for finding some results in this type of research studies. On the contrary, we do believe in the validity, in terms of practical—even clinical—application and scientific development of such studies. The concern is whether the results thereby obtained can provide more insight to the understanding of the ‘whole behind the experience’ as opposed to be limited to the psychological or neurological processes, mechanisms or biological, chemical-electric activities investigated.

- (a)

A previous/prior agreement on what we can scientifically define as experience (mechanism , process, feeling, emotion, thought, etc.)

- (b)

A possible methodological confirmation bias regarding not only the scientific techniques, technologies/instruments used, but also on the very location of such investigation.

Our intention here is certainly not to undermine the scientific rigor of experiments in this area, but to shed some light on the underlying theoretical issues that arise when attempting to combine what appears to be either two separate fields or two different aspects of a whole. Aside from the potential elements of dualism in this view, it is certainly beneficial to continue our scientific efforts in order to capture the ‘how’ of such phenomena. Science has certainly provided us with a better understanding of the psychopharmacology of mystical experiences, as we now can use specific chemical elements/synthetized components to elicit certain responses that are akin to spiritual perceptions and monitor their effect on subjects, be these effects deeply connected to the subjectivity of the individual experiencing them. Studies on ketamine, dimethyltryptamine, Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin, mescaline, for instance, have provided a very precise scientific understanding of what effects are produced by the use of chemically synthetized drugs or elements of spiritual, mystical, shamanic traditions such as ayahuasca, psilocybe mushrooms and peyote. Chemical reactions are also at the center of normal or abnormal (in the psychological sense, or as outlier in comparison to a mean, distant from baseline) neural functions. Thus, investigations on the substrata of certain traits of psychiatric disorders, such as psychotic or manic episodes, delusions or hallucinations exhibiting grandiosity or hyperreligiosity, can provide new insight on associations between these states and, for instance, cases of temporal lobe epilepsy (see the studies by Norman Geschwind or Vilayanur Ramachandran). On the opposite (from a theoretical point of view) side of the spectrum, we find the research by Andrew Newberg and Mario Beauregard on the effect/affect of spiritual and religious practices on brain activity and function, thereby providing support to mindfulness-based interventions as the ones found in behavioral medicine, motivational and positive psychology or mind-body medicine. Among the most important brain areas and neurological functions associated with this type of research, we find the limbic system and the cortical/subcortical structures, the frontal and parietal lobes. More in detail, this type of experiences often result in a (re)activation or increase of processes at the level of nucleus accumbens, frontal attentional regions, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, as well visual processing areas. In regard to the study of the links between areas usually covered in neurotheology, such as spiritual and religious practices in connection to neural activity, and psychiatry, especially regarding mental health disorders, we can refer to our previous analysis in Medical Philosophy (Tomasi 2016), especially mentioning that over 450 studies investigating the links between religious and spiritual factors in depression were published in the last 60 years (Bonelli et al. 2011). The meta-analysis indicated over 60% less depression and faster remission from it in those more religious or spiritual, or a reduction in depression severity in response to a religious or spiritual intervention, and “of the 178 most methodologically rigorous studies, 119 (67%) find inverse relationships between R/S and depression” (ibid.). However, among the most recent studies, the University of London created a survey9 (nearly 10,000 people from Great Britain, Chile, Estonia, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain) focused on the analysis of the ability of family doctors to predict depression from their patients’ worldview, which appeared to yield opposite result. The data in this study indicated that 10.3% of religious people had at least one severe episode of depression during the year; 10.5% of people with a spiritual worldview fell into deep depression and only 7% for secularists, with p < 0.001. Furthermore, it appeared that the more people viewed themselves as strongly religious or to have a strong religious faith, the greater the risk of severe depression. Although the results varied depending on the country, the study had found a very strong link between depression and religiosity. We should point out that, based on the results and the very focus of this research, “the notion that religious and spiritual life views enhance psychological well-being was not supported” (Ibid. 2016). Of course, a direct causal effect between religion and depression cannot be inferred as no further analysis post-data collection or within the study design was able to shed light on this aspect. More specifically, it is not clear whether people with depression are more prone to become more religious or at least find some relief in spiritual practices, or if those practices are the cause of depression. In the vast majority of studies, everything else being equal, religious or spiritual practices and beliefs are related to less depression, especially in the context of life stress, it is important to notice that our health is strongly influenced by the interaction between behavioral, cultural, developmental, environmental, genetic , social, etc., factors.