We know what happened the first time HTML was stretched beyond its limits: spacer GIFs, nested layout tables, font tags, “best viewed in my browser” badges, and fragmented standards. And worst of all, poorly trained content creators, whose limited knowledge of how things ought to be continues to plague us almost 15 years later.

What we have learned is that no language will be ideal for all

possible uses. HTML is a fantastic format for rich-text

documents. And we’ve learned how to layer it with CSS and script to make it

a pretty good platform for application frontends. We’ve even added an object

called XmlHttpRequest, named the

combination Ajax, and its phenomenal spread is the topic of dozens of books

of its own.

Ajax is just one of a growing number of pretty good UI platforms, each of them well-suited to the modern Web. They’re fast, functional, and cross-platform.

Now, here’s the catch: whether you’re developing with Ajax, Adobe’s Flash and Flex, Microsoft’s Silverlight, or any other web-based platform, your responsibilities go beyond web accessibility and into the world of software accessibility. Some of the rules change when dealing with software, and in the next two chapters, we explain what these new rules entail. We also show you what rules from HTML still apply.

Progressive enhancement uses web technologies in a layered fashion that allows everyone to access the basic content and functionality of a web page, using any browser or Internet connection, while also providing those with better bandwidth or more advanced browser software an enhanced version of the page.[19] | ||

| --Wikipedia, “Progressive Enhancement” (retrieved September 2, 2008) | ||

The key word here, I think, is unobtrusive. DHTML of this kind should just drop into place, providing a better user experience for people whose browsers can support it, and not affecting those whose browsers cannot.[20] | ||

| --Stuart Langridge, November 2002 | ||

Progressive enhancement is a framework; Unobtrusive JavaScript is applying the framework to JavaScript-based applications, and it represents a growing body of best practices. You may be asking yourself, “Is it possible to use JavaScript as an enhancement rather than a necessity? And even if it is, why would I?” Answers: Yes, it’s possible. Why would you? Well...

1996 was a landmark year in web history: Netscape introduced JavaScript (as “Mocha” and then “LiveScript”) as the nonprogrammer’s alternative to Java, at the end of 1995. Microsoft released a JavaScript dialect called JScript in August 1996—alongside a Visual Basic-like language called VBScript. That same year, the W3C published CSS1 as a W3C Recommendation. For the next few years, using scripting and styling was an exercise in translation and redundancy.

In 1998, things started looking up—folks agreed on ECMAScript and the DOM Level 1 was published as a W3C Recommendation. Scripting was starting to coalesce, but CSS was still broken. It would take another two years (plus lots of work by the Web Standards Project and the rise of the Opera browser) before browsers found common ground. However, there is still work to be done. Today, in 2008—12 years after the publication of CSS1, and 10 years after CSS2—you will still find many differences in support between browsers.

Looking back through this same time frame from the perspective of

someone using a screen reader in 1996, we didn’t find many problems caused

by scripts; few sites were using them, and they were still relatively

rudimentary. By 1998, we had identified most of the major issues with

scripts, which continue to exist today (see “Page Author Guidelines

Version 8”—http://trace.wisc.edu/archive/html_guidelines/central.htm#SCRIPT.Script).

At the time, the only recommendations for making scripts accessible were

to provide text alternatives, either through text-only versions of sites

or using the noscript element. There

wasn’t any major progress in making scripts accessible until WAI issued

the DHTML roadmap in 2005, which has evolved into a series of documents

that outline the Accessible Rich Internet Applications specification, or

WAI-ARIA.

Now, if we look at the development of mobile devices, there are more browsers available today than ever before, and the number is growing, as are the differences among them. Developers are encouraged to debug and test code in as many browsers as possible. With the wide array of devices and device capabilities out there, using progressive enhancement in your applications means they can have much wider reach. In the long run, it also means less work—progressive enhancement makes your application both backward compatible and future-proof.

Here are the core principles of progressive enhancement:

| ||

| --Wikipedia, “Progressive Enhancement” (retrieved September 2, 2008) | ||

Keep in mind that not all scripting events need to be made keyboard-accessible; it is the function that needs to be. We’re not trying to make the keyboard act like the mouse, we’re trying to make the keyboard a first-class input mechanism.

One of the most common accessibility issues is showing and hiding content: pop-up menus, expanding/collapsing outlines, and rollovers (to name a few). We discuss these issues with some of the most common techniques used to solve them, and then look at an example in depth to show what makes it work and why we want it to work this way.

Our primary goals are keyboard activation and appropriate reading order.

Your first task is to make the basic content and functionality of your menu accessible to all browsers by using sparse, semantic markup:

Mark menu items as links

Organize links in nested lists

Create subpages that mirror the pop-up submenu pages

After creating a solid foundation, manage the layout with externally linked CSS. Finally, enhance the behavior of your site with unobtrusive, externally linked JavaScript. Here are some things to watch out for when you use CSS and scripting.

There are many beautiful examples that use :hover to create a CSS-only pop-up menu, in

which the code is elegant and works well across browsers and

platforms. The problem is that the :hover pseudoselector in CSS is only

activated by mouse movements and is usually associated with an

inactive element, such as a heading or list item. In this section, we

focus on the issues with :hover on

active elements, and in the next section, we discuss issues with using

:hover with inactive

elements.

The following example uses :hover to display a submenu:

/* css */

#nav ul li:hover ul

{

display:block; position:absolute; top:0;

left:164px; border: 1px solid #6C4571

}

...

/* html */

<div id="nav">

<ul>

<li><a href="first.html" class="first">one</a>

<ul>

<li><a href="sub-two.html">sub-one</a></li>

<li><a href="sub-three.html">sub-two</a></li>

</ul>

</li>

...This works great for someone using a mouse, but to make this

accessible by a keyboard or touchscreen, your first inclination may be

to look to the :focus

pseudoselector. Unfortunately, :focus is only active while the current

element has focus. In the example just shown, when the parent (menu

item) loses focus, the children (submenu items) disappear.

You also need to consider how the children are hidden: using

display:none or positioning them

offscreen. If you use display:none,

there is no way to tab to the children—they never receive focus and

are never displayed. If you position them offscreen, you can tab to

them, but they won’t be displayed. Because positioning the ul offscreen hides the children and because

the ul can’t take focus, there is

no way to override the positioning properties of each element. When

links are hidden offscreen, a person must tab to every link in the

menu; there is no way to skip between menu items.

Note

The keyboard support for visibility:hidden and display:none is the

same. The difference between the two is that with visibility:hidden browsers reserve space

for the elements, whereas with display:none space is not created until

the element is made visible.

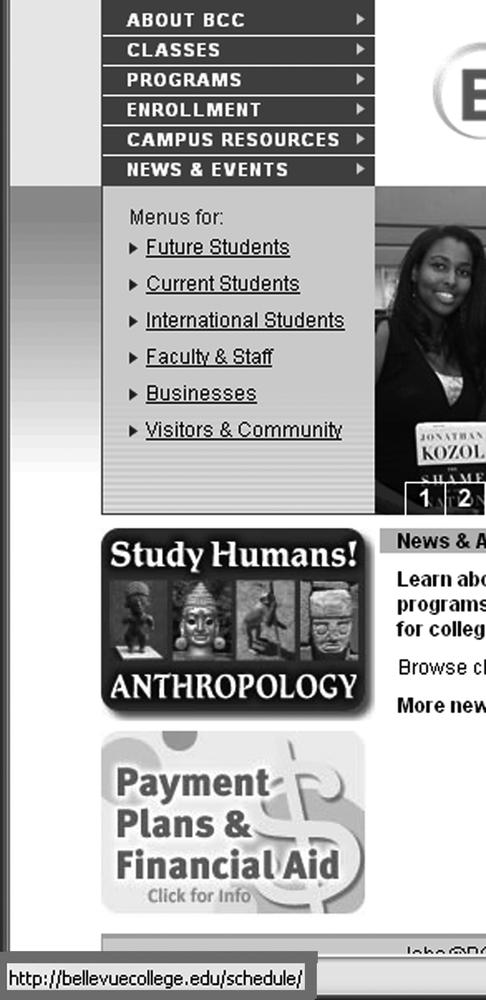

The Bellevue Community College home page organizes links into

nested lists and relies on the :hover pseudoselector to position and

show/hide submenus. Figure 8-1 shows the BCC

home page submenus of “Classes,” which users open by hovering over

“Classes” and “Class Schedules” with the mouse.

When tabbing through the BCC site, you will only know that you have reached one of the submenu items by reading the status bar of the browser. Figure 8-2 shows the BCC home page with the keyboard focus on the “Classes” menu item.

Pressing the Tab key once more moves focus to the first submenu item of “Classes,” but it is displayed offscreen. A screen reader doesn’t care that it is offscreen and will read and interact with the menu as though it were in the viewport. However, for someone using a keyboard because of a physical disability, the only way to know that the submenu has focus is to look at the status bar. See Figure 8-3.

Because the BCC site is designed with accessibility in mind, if you press Enter while “About BCC” has keyboard focus, it activates the link to the About BCC page that lists all of the submenu items on that page, shown in Figure 8-4.

Therefore, this is technically accessible. However, navigating to the “Classes” link requires pressing the Tab key 20 times. Figure 8-5 shows the nesting of the submenu items and the number of links between the “About BCC” and “Classes” submenus.

We could leave this as it is, as it’s technically accessible to people who are not using a mouse—whether they are using a screen reader, using the keyboard only (e.g., a mobile device), or using a touchscreen (e.g., an iPhone).

But, what if you wanted to make it more accessible? There are several paths to travel, and none is perfect today:

Note

BCC is working toward a more accessible solution and should have something in place soon after the publication of this book.

With all of these options, we are interacting with the menus as links rather than simply as menus. Table 8-1 summarizes the differences between expected behaviors of interacting with links and system menus via the keyboard.

Table 8-1. Keypresses and their outcomes, with links versus system menus

Key press | Expected behavior with a link | Expected behavior with a system menu |

|---|---|---|

Tab | Move to next link on the page | Windows XP: error. Focus does not move. Mac OS X: move focus to next top-level menu. |

Right arrow | Web browser: none Assistive technology: read the link text character by character or move to the next link | When the menu bar or a menu item has focus, pressing the right arrow causes focus to move to the next menu, or if the current menu item has a submenu, it will open the submenu. |

Escape | None | Close the open menu or submenu (Windows then returns focus to the parent menu item, while in Mac OS X the focus returns to the application window). |

Enter | Activate the link | If the menu item has a submenu, open the submenu; otherwise, activate the current menu item. |

Note

Typical keyboard behaviors for widgets are being debated and documented in the DHTML Style Guide (http://dev.aol.com/dhtml_style_guide). Many of the same people working on this guide are also working on ARIA, and the two documents have been feeding off of one another for some time.

Building a menu out of links puts us somewhere between links and

system menus. Using the BCC site as an example, we could add an

onclick event to each link so that instead of

activating the link and opening a new page, it could display the

submenu item. Pressing Tab again could take us to the first submenu

item. But, what do we do about other keystrokes? Do we trap arrow keys

and the Escape key and replicate system behavior? We tried this out

and had a few people test it. They found it confusing.

Many people recommend the “Ultimate Drop Down Menu 4” by James Edwards (http://www.udm4.com/). There are a number of things we like about UDM4. First and foremost, it’s one of the cleanest implementations of a drop-down menu that we’ve encountered. It uses standard XHTML and separates its CSS and JavaScript into external files. It’s extremely customizable. And its menu markup uses HTML headings, which allow screen readers to navigate with their own built-in headings mode. Among the commercial menu products out there, we think it’s one of the best.

That’s not to say it’s perfect. When we tested it with versions of the JAWS and NVDA screen readers, we found some anomalies that prevent it from being used like a system menu (although the screen readers themselves share some responsibility for this, and we had more trouble with nearly every other menu script out there).

And the licensing terms may not appeal to many people. While it can be used at no charge on noncommercial sites, those users are required by license to link to UDM4’s site on every page with a UDM4 menu. Commercial licenses are available on various terms, either for a one-time or subscription fee, but they also contain restrictions that you should read before purchasing the product.

If you can live with UDM4’s licensing regime, it’s a good product and can save you a lot of time. But we’ve known many folks who can’t agree to its terms for one reason or another, and we think it’s important to show how to achieve our universal design goals in a menu system, without the licensing restrictions. So we wrote an open source menu script of our own, which you can download at http://ud4wa.com.

Limit the number of menu items.

Provide subpages that link to all of the submenu items.

Test with intended audience to determine what kind of behavior they expect.

Pseudoselectors such as :focus and :active work only on active elements such as

links and input elements, and they do not work in Microsoft’s Internet

Explorer (version 7 and earlier). Those using a screen reader can

navigate to inactive elements (such as headings and list items) so

that they may be read aloud. But this doesn’t activate :focus because the screen reader is not

moving the browser focus but instead is moving its own virtual cursor

and therefore its own virtual focus.

In Figure 8-6, the course names are marked as labels.

Clicking on a course name expands to show a course description, as shown in Figure 8-7.

The markup is very elegant. We particularly like using label to label a div:

<label style="cursor: pointer;" class="collapsible" for="section6"><img src="courses.aspx_files/closed.jpg" alt=" [expand] ">IMT530 – Organization of Information and Resources</label> <div style="display: none;" class="collapsed" id="section6"> <p class="content">Introduction to issues in organization of information and information objects including: analysis of intellectual and physical characteristics of information objects; use of metadata and metadata standards for information systems; theory of classification, including semantic relationships and facet analysis; creation of controlled vocabularies; and display and arrangement. </p> </div>

The problem for keyboard users is that label elements cannot receive focus, even though the HTML spec says they should.

One aspect of ARIA that we cover here is tabindex. According to the HTML 4.01

specification, tabindex applies

only to the A, AREA, BUTTON, INPUT, OBJECT, SELECT, and TEXTAREA elements (http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/interact/forms.html#adef-tabindex).

tabindex values can be any number

between 0 and 32,767 and are navigated according to the following

rules:

Elements with a positive

tabindexvalue are navigated in order of lowesttabindexvalue to highest. Elements with the sametabindexvalue are navigated in document source order.Elements without a

tabindexattribute or with atabindexof “0” are navigated next and in the order they appear in the document source.Disabled elements are not included in the tab order.

ARIA slightly changes the rules by allowing any visible element

to be added to the tab order. ARIA also adds a negative value for

tabindex. An element with a

negative tabindex is not added to

the tab order, but it can receive focus via the mouse or JavaScript

element.focus(). This allows an

application to support arrow key navigation—as we’ll see in the next

chapter.

<div tabindex="-1">...</div> <p><a href="example1.html">Example link 1</a></p> <label style="cursor: pointer;" class="collapsible" for="section6" tabindex="0"><img src="courses.aspx_files/closed.jpg" alt=" [expand] ">IMT530 - Organization of Information and Resources</label> <div style="display: none;" class="collapsed" id="section6"> <p class="content">Introduction to issues in organization of information and information objects including: analysis of intellectual and physical characteristics of information objects; use of metadata and metadata standards for information systems; theory of classification, including semantic relationships and facet analysis; creation of controlled vocabularies; and display and arrangement. </p> </div> <p><a href="example2.html" tabindex="1">Example link 2</a></p>

According to the ARIA-enhanced tabindex scheme, the tab order for this code would be as follows:

Example link 2—because

tabindex="1"Example link 1—because it is next in the document source order

The IMT530 label—because it is next in the document source order and has

tabindex="0"

The div with tabindex="-1" is

not included in the tab order.

Using :hover to highlight

items that can not receive focus (such as lines in a table) is cool—it

helps people who are visual learners. The person using a screen reader will know which item

has focus—as only one item at a time can have focus. For example, in

the following code, the current row is highlighted on :hover:

<style type="text/css">

tr:hover {background-color: #FFCC33;}

</style>Note that we’re doing this with a style sheet rather than a

scripted onmouseover(). When possible, we prefer

using CSS to scripting.

Catching mouse events with onmouseover has similar issues to :hover—it may work for someone using a mouse

but not for keyboard or mobile users. Even modern mobile devices such

as the iPhone have trouble with onmouseover, since they track only users

tapping on the screen.

There’s no reason not to use onmouseover per se. However, if you do use

it for anything more complex than to call out the presence of a link

(say, to show or hide tiles in a trivia game), you will need to use

another event as well, for example, onfocus, onactivate, onkeypress, or even onclick.

For more information, WebAIM’s Creating Accessible JavaScript: JavaScript Event Handlers provides a great overview (http://www.webaim.org/techniques/javascript/eventhandlers.php).