“It would be possible to describe absolutely everything scientifically, but it would make no sense. It would be without meaning, as if you described a Beethoven symphony as a variation of wave pressure.”

—Albert Einstein

Imagine holding the end of a long rope in your hand, with the other end attached to a wall. Move your hand up and down, and you’ll create a wave that travels along the rope, from your hand to the wall. This simple example displays the basic idea of a mechanical wave: a disturbance transmitted by a medium from one point to another, without the medium itself being transported. In this chapter, we will discuss waves and their characteristics.

Let’s take a look at a long rope. Someone standing near the system would see peaks and valleys actually moving along the rope, in what’s called a traveling wave.

What features of the wave can we see in this point of view? Well, we can see the points at which the rope has its maximum vertical displacement above the horizontal; these points are called crests. The points at which the rope has its maximum vertical displacement below the horizontal are called troughs. These crests and troughs repeat themselves at regular intervals along the rope, and the distance between two adjacent crests (or two adjacent troughs) is the length of one wave, and is called the wavelength (λ, lambda). Also, the maximum displacement from the horizontal equilibrium position of the rope is also measurable; this is known as the amplitude (A) of the wave.

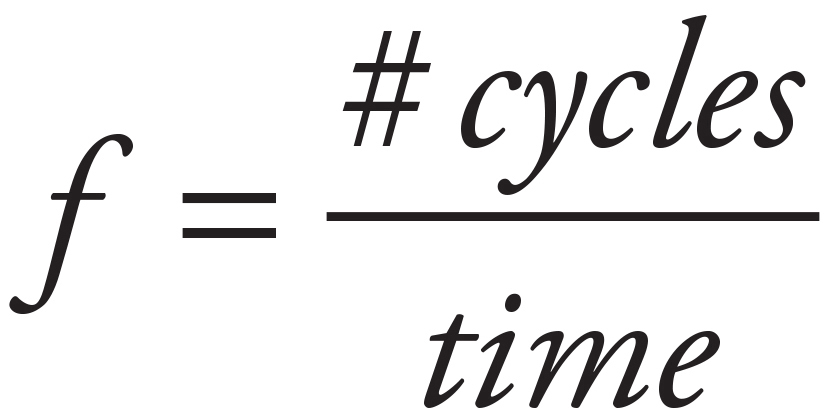

Since the direction in which the rope oscillates (vertically) is perpendicular to the direction in which the wave propagates (or travels, horizontally), this wave is transverse. The time it takes for one complete vertical oscillation of a point on the rope is called the period, T, of the wave, and the number of cycles it completes in one second is called its frequency, f. The period and frequency are established by the source of the wave and, of course, T = 1/f.

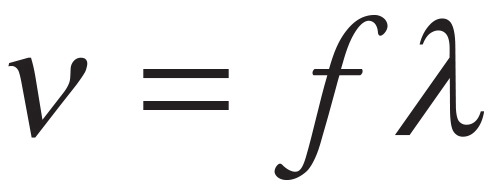

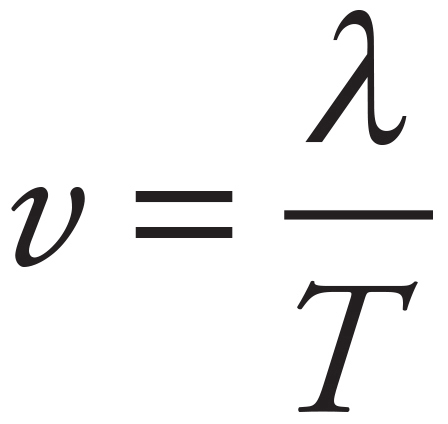

In addition to the amplitude, period, frequency, and wavelength, another important characteristic of a traveling wave is its speed, v. Look at the second figure on the previous page and imagine the visible point on the rope moving from its crest position, down to its trough position, and then back up to the crest position. The wave took a time period of T to move a distance of one wavelength, signified by λ. Therefore, the equation distance = rate × time becomes

The simple equation v = λf shows how the wave speed, wavelength, and frequency are interconnected. It’s the most basic equation in wave theory.

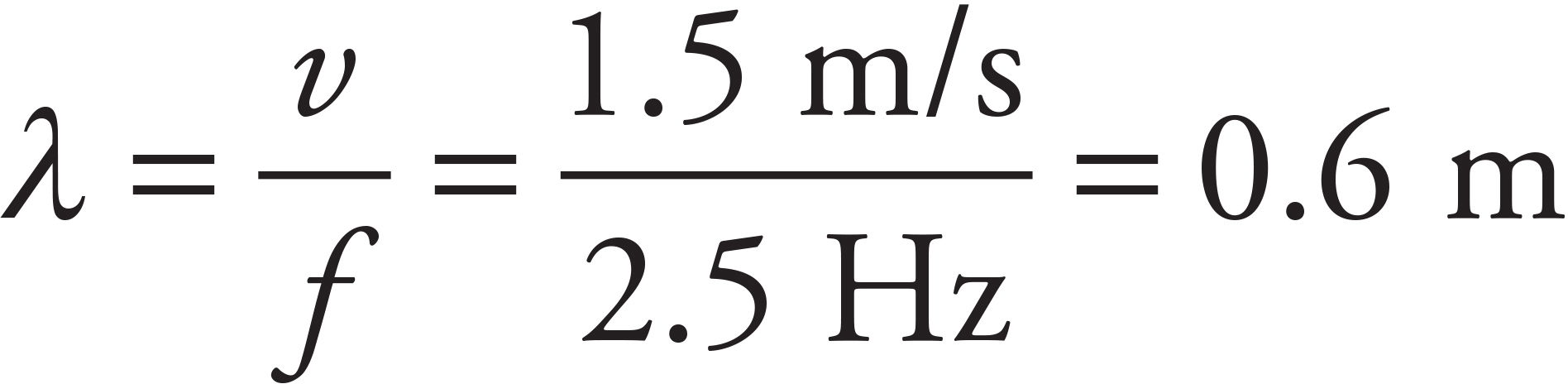

Example 1 A traveling wave on a rope has a frequency of 2.5 Hz. If the speed of the wave is 1.5 m/s, what are its period and wavelength?

Solution. The period is the reciprocal of the frequency:

and the wavelength can be found from the equation λf = v:

Example 2 The period of a traveling wave is 0.5 s, its amplitude is 10 cm, and its wavelength is 0.4 m. What are its frequency and wave speed?

Solution. The frequency is the reciprocal of the period: f = 1/T = 1/(0.5 s) = 2 Hz. The wave speed can be found from the equation v = λf:

v = λf = (0.4 m)(2 Hz) = 0.8 m/s

Note that the frequency, period, wavelength, and wave speed have nothing to do with the amplitude.

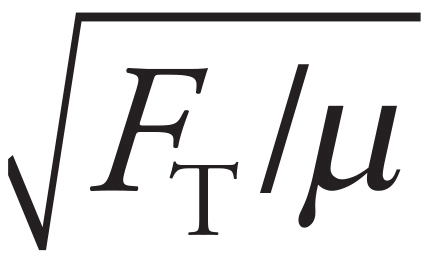

We can also derive an equation for the speed of a transverse wave on a stretched string or rope. Let the mass of the string be m and its length be L; then its linear mass density (μ) is m/L. If the tension in the string is FT, then the speed of a traveling transverse wave on this string is given by

Note that v depends only on the physical characteristics of the string: its tension and linear density. So, because v = λf for a given stretched string, varying f will create different waves that have different wavelengths, but v will not vary.

Notice that the equation for the wave speed on a stretched rope shows that v does not depend on f (or λ). While this may seem to contradict the first equation, v = λf, it really doesn’t. The speed of the wave depends on the characteristics of the rope; how tense it is and what it’s made of. We can wiggle the end at any frequency we want, and the speed of the wave we create will be a constant. However, because λf = v must always be true, a higher f will mean a shorter λ and a lower f will mean a longer λ. Thus, changing f doesn’t change v: it changes λ. This brings up our first big wave rule:

Wave Rule #1: The speed of a wave is determined by the type of wave and the characteristics of the medium, not by the frequency.

Rule #1 deals with a wave in a single medium. What travels to you faster, a yell or a whisper? Neither does; they both travel to you at the speed of sound. In a single medium, the speed of a wave is constant and is represented by an inverse relationship between wavelength and frequency: λ1f1 = λ2f2.

Notice that two different types of waves can move with different speeds through the same medium. For example, sound and light move through air with very different speeds.

Our second wave rule addresses what happens when a wave passes from one medium into another. Because wave speed is determined by the characteristics of the medium, a change in the medium causes a change in wave speed, but the frequency won’t change.

Wave Rule #2: When a wave passes into another medium, its speed changes, but its frequency does not.

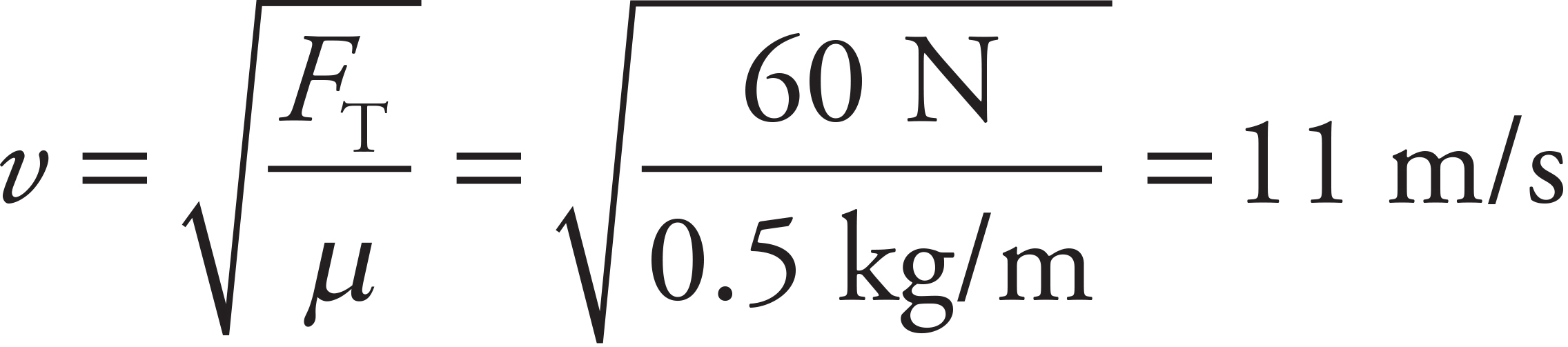

Example 3 A horizontal rope with linear mass density μ = 0.5 kg/m sustains a tension of 60 N. The non-attached end is oscillated vertically with a frequency of 4 Hz.

(a) What are the speed and wavelength of the resulting wave?

(b) How would you answer these questions if f were increased to 5 Hz?

Solution.

(a) Wave speed is established by the physical characteristics of the rope:

With v, we can find the wavelength: λ = v/f = (11 m/s)/(4 Hz) = 2.8 m.

(b) If f were increased to 5 Hz, then v would not change, but λ would; the new wavelength would be

λ′ = v/f′ = (11 m/s)/(5 Hz) = 2.2 m

Example 4 Two ropes of unequal linear densities are connected, and a wave is created in the rope on the left, which propagates to the right, toward the interface with the heavier rope.

When a wave strikes the boundary to a new medium (in this case, the heavier rope), some of the wave’s energy is reflected and some is transmitted. The frequency of the transmitted wave is the same, but the speed and wavelength are not. How do the speed and wavelength of the incident wave compare to the speed and wavelength of the wave as it travels through Rope #2?

Solution. Since the wave enters a new medium, it will have a new wave speed. Because Rope #2 has a greater linear mass density than Rope #1, and because v is inversely proportional to the square root of the linear mass density, the speed of the wave in Rope #2 will be less than the speed of the wave in Rope #1. Since v = λf must always be satisfied and f does not change, the fact that v changes means that λ must change too. In particular, since v decreases upon entering Rope #2, so will λ.

When two or more waves meet, the displacement at any point of the medium is equal to the algebraic sum of the displacements due to the individual waves. This is superposition. The figure below shows two wave pulses traveling toward each other along a stretched string. Note that when they meet and overlap (interfere), the displacement of the string is equal to the sum of the individual displacements, but after they pass, the wave pulses continue, unchanged by their meeting.

If the two waves have displacements of the same sign when they overlap, the combined wave will have a displacement of greater magnitude than either individual wave; this is called constructive interference. Similarly, if the waves have opposite displacements when they meet, the combined waveform will have a displacement of smaller magnitude than either individual wave; this is called destructive interference. If the waves travel in the same direction, the amplitude of the combined wave depends on the relative phase of the two waves. If the waves are exactly in phase—that is, if crest meets crest and trough meets trough—then the waves will constructively interfere completely, and the amplitude of the combined wave will be the sum of the individual amplitudes. However, if the waves are exactly out of phase—that is, if crest meets trough and trough meets crest—then they will destructively interfere completely, and the amplitude of the combined wave will be the difference between the individual amplitudes. In general, the waves will be somewhere in between exactly in phase and exactly out of phase.

Example 5 Two waves, one with an amplitude of 8 cm and the other with an amplitude of 3 cm, travel in the same direction on a single string and overlap. What are the maximum and minimum amplitudes of the string while these waves overlap?

Solution. The maximum amplitude occurs when the waves are exactly in phase; the amplitude of the combined waveform will be 8 cm + 3 cm = 11 cm. The minimum amplitude occurs when the waves are exactly out of phase; the amplitude of the combined waveform will then be 8 cm ‒ 3 cm = 5 cm. Without more information about the relative phase of the two waves, all we can say is that the amplitude will be at least 5 cm and no greater than 11 cm.

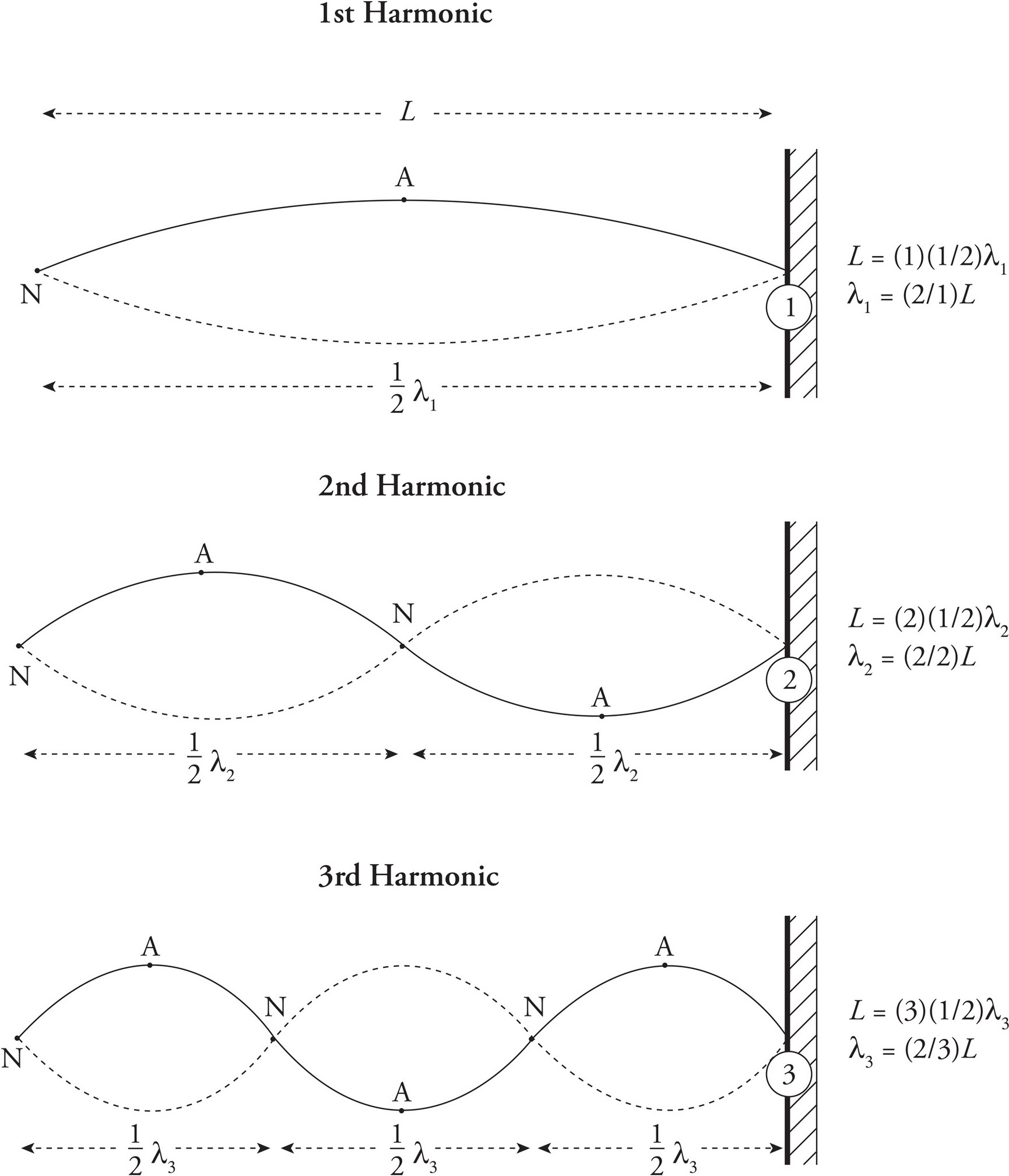

When our prototype traveling wave on a string strikes the wall, the wave will reflect and travel back toward us. The string now supports two traveling waves; the wave we generated at our end, which travels toward the wall, and the reflected wave. What we actually see on the string is the superposition of these two oppositely directed traveling waves, which have the same frequency, amplitude, and wavelength. If the length of the string is just right, the resulting pattern will oscillate vertically and remain fixed. The crests and troughs no longer travel down the length of the string. This is a standing wave.

The right end is fixed to the wall, and the left end is oscillated through a negligibly small amplitude so that we can consider both ends to be essentially fixed (no vertical oscillation). The interference of the two traveling waves results in complete destructive interference at some points (marked N in the figure on the next page), and complete constructive interference at other points (marked A in the figure). Other points have amplitudes between these extremes. Note another difference between a traveling wave and a standing wave: while every point on the string had the same amplitude as the traveling wave went by, each point on a string supporting a standing wave has an individual amplitude. The points marked N are called nodes, and those marked A are called antinodes.

Nodes and antinodes always alternate, they’re equally spaced, and the distance between two successive nodes (or antinodes) is equal to  . This information can be used to determine how standing waves can be generated. The following figures show the three simplest standing waves that our string can support. The first standing wave has one antinode, the second has two, and the third has three. The length of the string in all three diagrams is L.

. This information can be used to determine how standing waves can be generated. The following figures show the three simplest standing waves that our string can support. The first standing wave has one antinode, the second has two, and the third has three. The length of the string in all three diagrams is L.

For the first standing wave, notice that L is equal to 1( ). For the second standing wave, L is equal to 2(

). For the second standing wave, L is equal to 2( ), and for the third, L = 3(

), and for the third, L = 3( ). A pattern is established: a standing wave can form only when the length of the string is a multiple of

). A pattern is established: a standing wave can form only when the length of the string is a multiple of  :

:

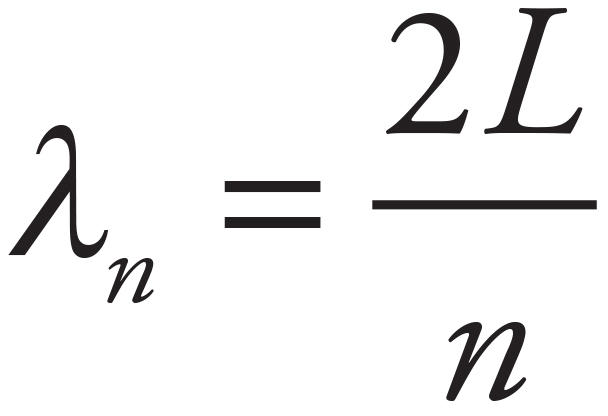

Solving this for the wavelength, we get

These are called the harmonic (or resonant) wavelengths, and the integer n is known as the harmonic number.

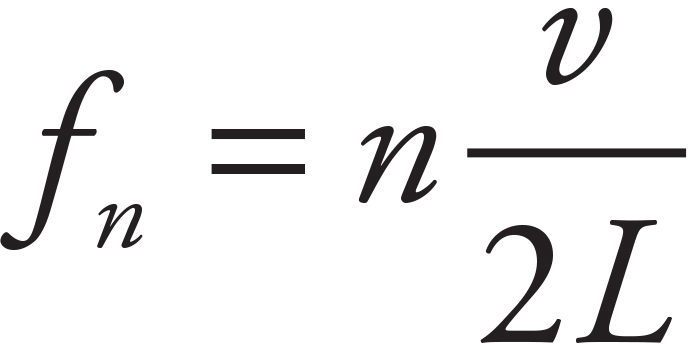

Since we typically have control over the frequency of the waves we create, it’s more helpful to figure out the frequencies that generate a standing wave. Because λf = v, and because v is fixed by the physical characteristics of the string, the special λs found above correspond to equally special frequencies. From fn = v/λn, we get

These are the harmonic (or resonant) frequencies. A standing wave will form on a string if we create a traveling wave whose frequency is the same as a resonant frequency. The first standing wave, the one for which the harmonic number, n, is 1, is called the fundamental standing wave. From the equation for the harmonic frequencies, we see that the nth harmonic frequency is simply n times the fundamental frequency:

fn = nf1

Similarly, the nth harmonic wavelength is equal to λ1 divided by n. Therefore, by knowing the fundamental frequency (or wavelength), all the other resonant frequencies and wavelengths can be determined.

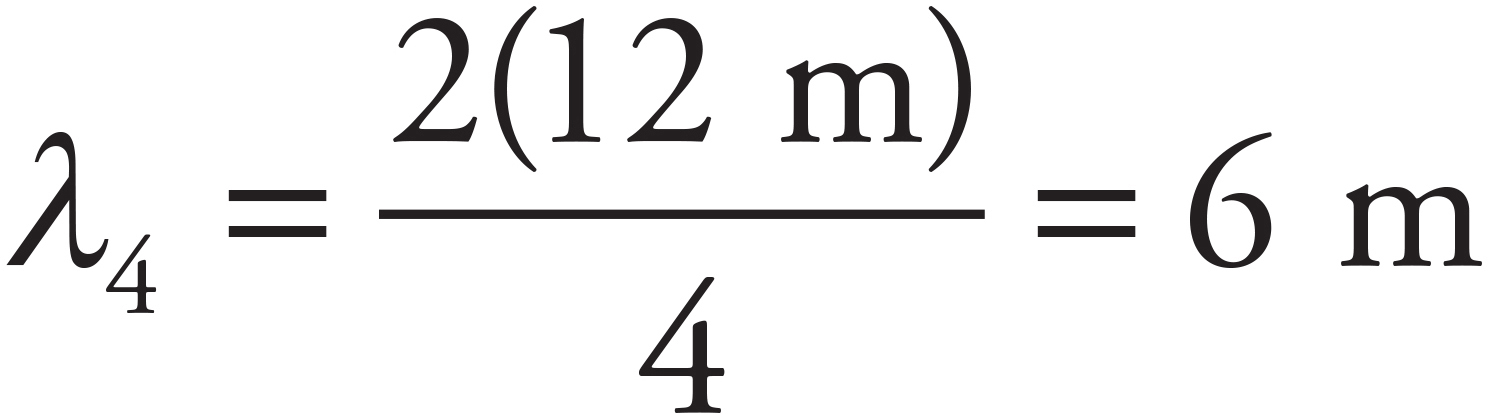

Example 6 A string of length 12 m that’s fixed at both ends supports a standing wave with a total of 5 nodes. What are the harmonic number and wavelength of this standing wave?

Solution. First, draw a picture.

This shows that the length of the string is equal to 4( ), so

), so

This is the fourth-harmonic standing wave, with wavelength λ4 (because the expression above matches λn = 2L/n for n = 4). Since L = 12 m, the wavelength is

Example 7 A string of length 10 m and mass 300 g is fixed at both ends, and the tension in the string is 40 N. What is the frequency of the standing wave for which the distance between a node and the closest antinode is 1 m?

Solution. Because the distance between two successive nodes (or successive antinodes) is equal to  , the distance between a node and the closest antinode is half this, or

, the distance between a node and the closest antinode is half this, or  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  = 1 m, so λ = 4 m. Since the harmonic wavelengths are given by the equation λn = 2L/n, we can find that

= 1 m, so λ = 4 m. Since the harmonic wavelengths are given by the equation λn = 2L/n, we can find that

The frequency of the fifth harmonic is

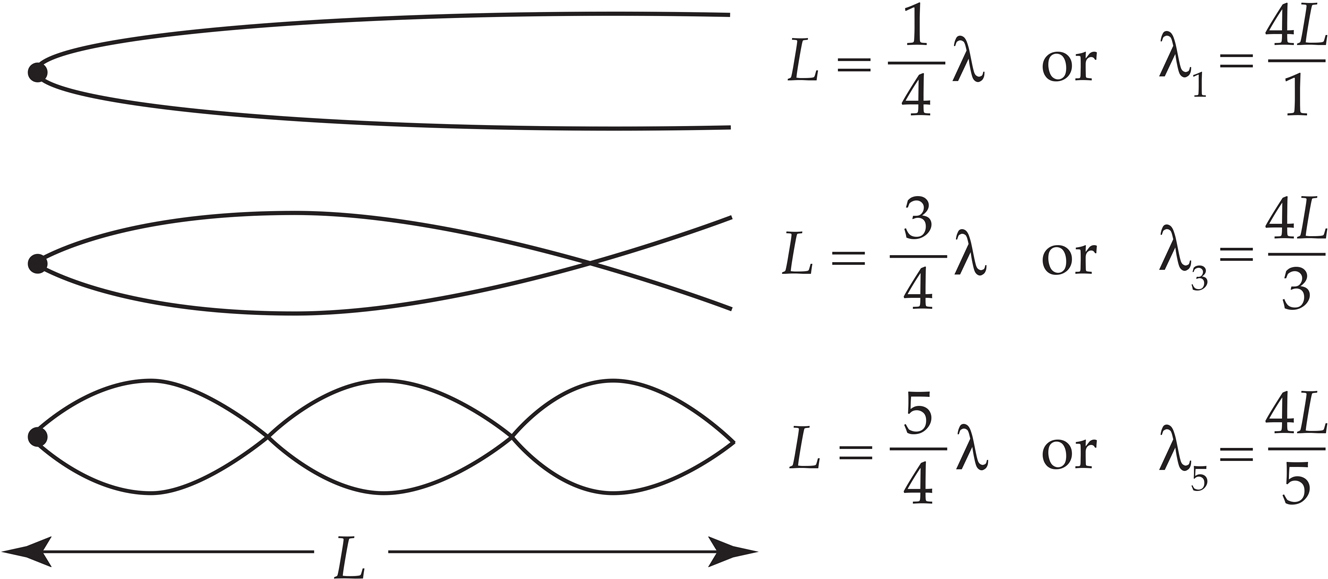

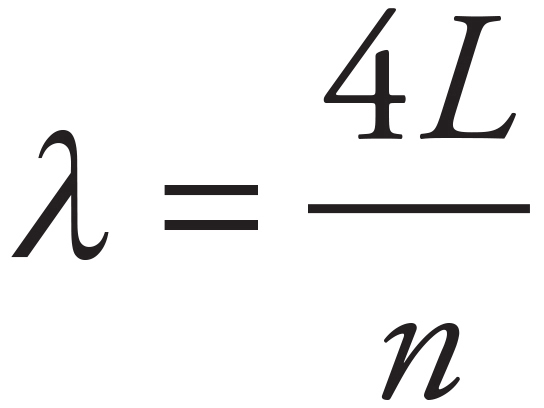

If you attached a rope or string to a ring that could slide up and down a pole without friction, you would make a rope that is fixed at one end but free at another end. This would create nodes at the closed end and antinodes at the open end. Below are some possible examples of this.

If one end of the rope is free to move, standing waves can form for wavelengths of  or by frequencies of

or by frequencies of  , where L is the length of the rope, v is the speed of the wave, and n must be an odd integer.

, where L is the length of the rope, v is the speed of the wave, and n must be an odd integer.

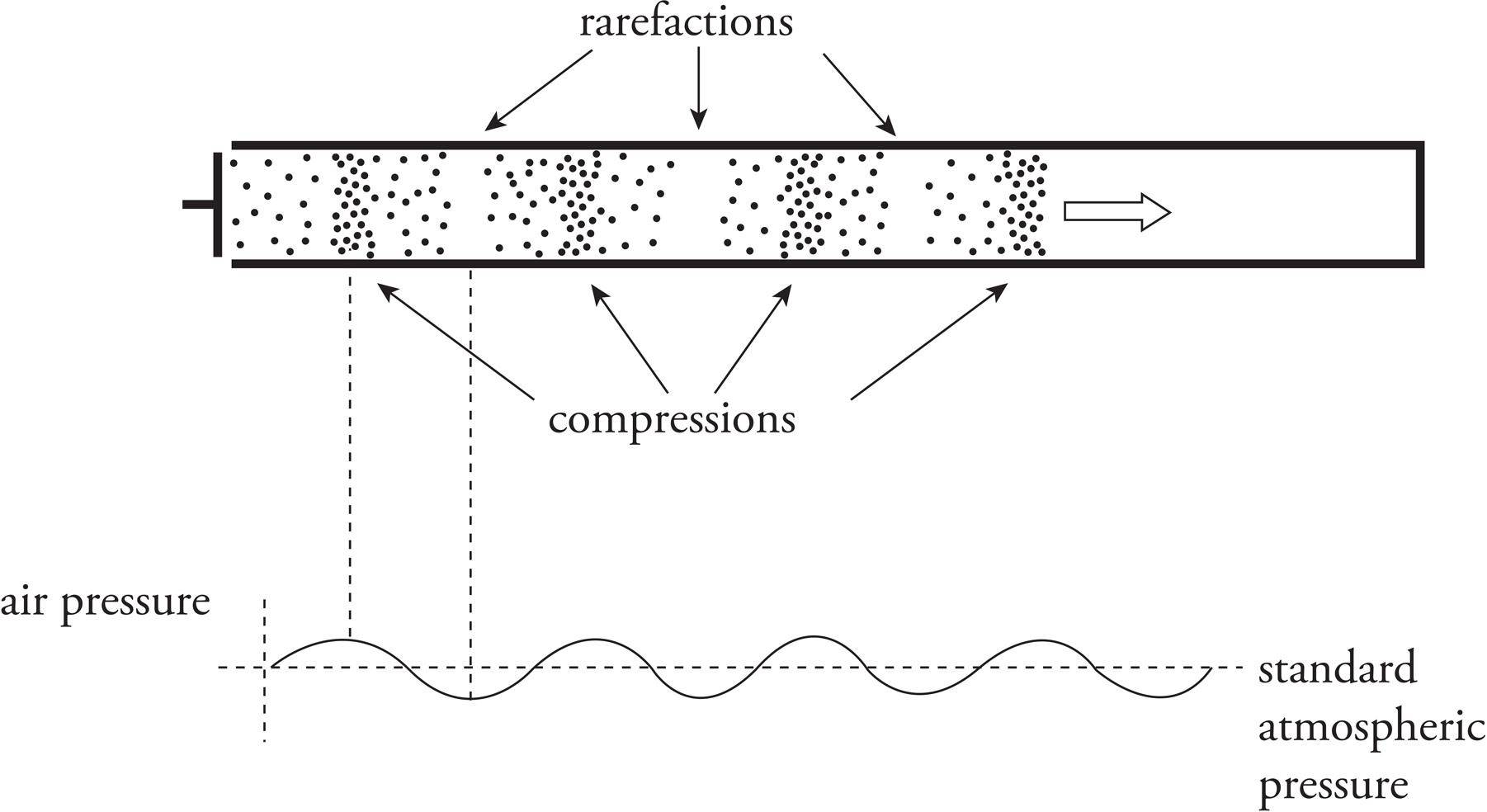

Sound waves are produced by the vibration of an object, such as your vocal cords, a plucked string, or a jackhammer. The vibrations cause pressure variations in the conducting medium (which can be gas, liquid, or solid), and if the frequency is between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz, the vibrations may be detected by human ears and perceived as sound. The variations in the conducting medium can be positions at which the molecules of the medium are bunched together (where the pressure is above normal), which are called compressions, and positions where the pressure is below normal, called rarefactions. In the figure below, a vibrating diaphragm sets up a sound wave in an air-filled tube. Each dot represents many, many air molecules:

An important difference between sound waves and the waves we’ve been studying on stretched strings is that the molecules of the medium transmitting a sound wave move parallel to the direction of wave propagation, rather than perpendicular to it. For this reason, sound waves are said to be longitudinal. Despite this difference, all of the basic characteristics of a wave—amplitude, wavelength, period, frequency—apply to sound waves as they did for waves on a string. Furthermore, the all-important equation λf = v also holds true. However, because it’s very difficult to draw a picture of a longitudinal wave, an alternate method is used: we can graph the pressure as a function of position:

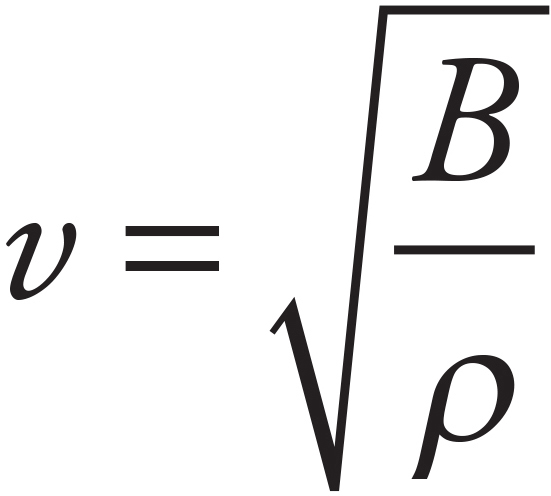

The speed of a sound wave depends on the medium through which it travels. In particular, it depends on the density (ρ) and on the bulk modulus (B), a measure of the medium’s response to compression. A medium that is easily compressible, like a gas, has a low bulk modulus; liquids and solids, which are much less easily compressed, have significantly greater bulk modulus values. For this reason, sound generally travels faster through solids than through liquids and faster through liquids than through gases.

The equation that gives a sound wave’s speed in terms of ρ and B is

The speed of sound through air can also be written in terms of air’s mean pressure, which is temperature dependent. At room temperature (approximately 20°C) and normal atmospheric pressure, sound travels at 343 m/s. This value increases as air warms.

Example 8 A sound wave with a frequency of 300 Hz travels through the air.

(a) What is its wavelength?

(b) If its frequency increased to 600 Hz, what are the wave’s speed and wavelength?

Solution.

(a) Using v = 343 m/s for the speed of sound through air, we find that

(b) Unless the ambient pressure or the temperature of the air changed, the speed of sound would not change. Wave speed depends on the characteristics of the medium, not on the frequency, so v would still be 343 m/s. However, a change in frequency would cause a change in wavelength. Since f increased by a factor of 2, λ would decrease by a factor of 2, to  (1.14 m) = 0.57 m.

(1.14 m) = 0.57 m.

Example 9 A sound wave traveling through water has a frequency of 500 Hz and a wavelength of 3 m. How fast does sound travel through water?

Solution. v = λf = (3 m)(500 Hz) = 1,500 m/s.

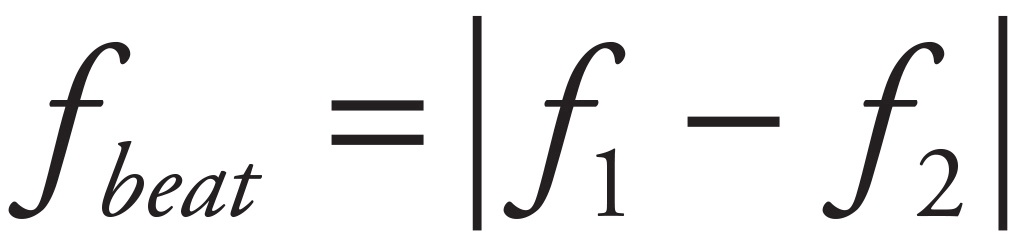

If two sound waves whose frequencies are close but not identical interfere, the resulting sound modulates in amplitude, becoming loud, then soft, then loud, then soft. This is due to the fact that as the individual waves travel, they are in phase, then out of phase, then in phase again, and so on. Therefore, by superposition, the waves interfere constructively, then destructively, then constructively, and so on. When the waves interfere constructively, the amplitude increases, and the sound is loud; when the waves interfere destructively, the amplitude decreases, and the sound is soft. Each time the waves interfere constructively, producing an increase in sound level, we say that a beat has occurred. The number of beats per second, known as the beat frequency, is equal to the difference between the frequencies of the two combining sound waves:

fbeat = |f1 ‒ f2|

If frequencies f1 and f2 match, then the combined waveform doesn’t waver in amplitude, and no beats are heard.

Example 10 A piano tuner uses a tuning fork to adjust the key that plays the A note above middle C (whose frequency should be 440 Hz). The tuning fork emits a perfect 440 Hz tone. When the tuning fork and the piano key are struck, beats of frequency 3 Hz are heard.

(a) What is the frequency of the piano key?

(b) If it’s known that the piano key’s frequency is too high, should the piano tuner tighten or loosen the wire inside the piano in order to tune it?

Solution.

(a) Since fbeat = 3 Hz, the tuning fork and the piano string are off by 3 Hz. Since the fork emits a tone of 440 Hz, the piano string must emit a tone of either 437 Hz or 443 Hz. Without more information, we can’t determine which.

(b) If we know that the frequency of the tone emitted by the out-of-tune string is too high (that is, it’s 443 Hz), we need to find a way to lower the frequency. Remember that the resonant frequencies for a stretched string fixed at both ends are given by the equation f = nv/2L, and that v =  . Since f is too high, v must be too high. To lower v, we must reduce FT. The piano tuner should loosen the string and listen for beats again, adjusting the string until the beats disappear.

. Since f is too high, v must be too high. To lower v, we must reduce FT. The piano tuner should loosen the string and listen for beats again, adjusting the string until the beats disappear.

Just as standing waves can be set up on a vibrating string, standing sound waves can be established within an enclosure. In the figure below, a vibrating source at one end of an air-filled tube produces sound waves that travel the length of the tube.

These waves reflect off the far end, and the superposition of the forward and reflected waves can produce a standing wave pattern if the length of the tube and the frequency of the waves are related in a certain way.

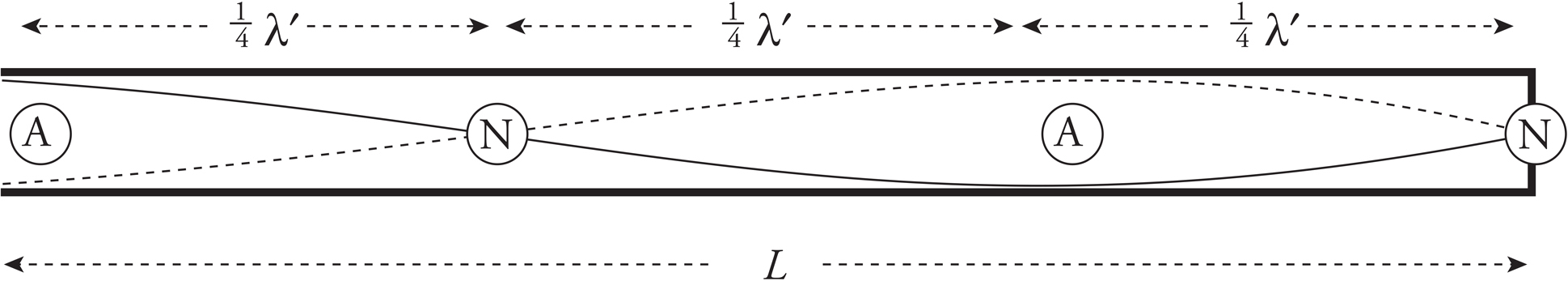

Notice that air molecules at the far end of the tube can’t oscillate horizontally because they’re up against a wall. So the far end of the tube is a displacement node. But the other end of the tube (where the vibrating source is located) is a displacement antinode. A standing wave with one antinode (A) and one node position (N) can be depicted as follows:

Although sound waves in air are longitudinal, here we’ll show the wave as transverse so that it’s easier to determine the wavelength. Since the distance between an antinode and an adjacent node is always  of the wavelength, the length of the tube, L, in the figure above is

of the wavelength, the length of the tube, L, in the figure above is  the wavelength. This is the longest standing wavelength that can fit in the tube, so it corresponds to the lowest standing wave frequency, the fundamental:

the wavelength. This is the longest standing wavelength that can fit in the tube, so it corresponds to the lowest standing wave frequency, the fundamental:

Our condition for resonance was a node at the closed end and an antinode at the open end. Therefore, the next higher frequency standing wave that can be supported in this tube must have two antinodes and two nodes:

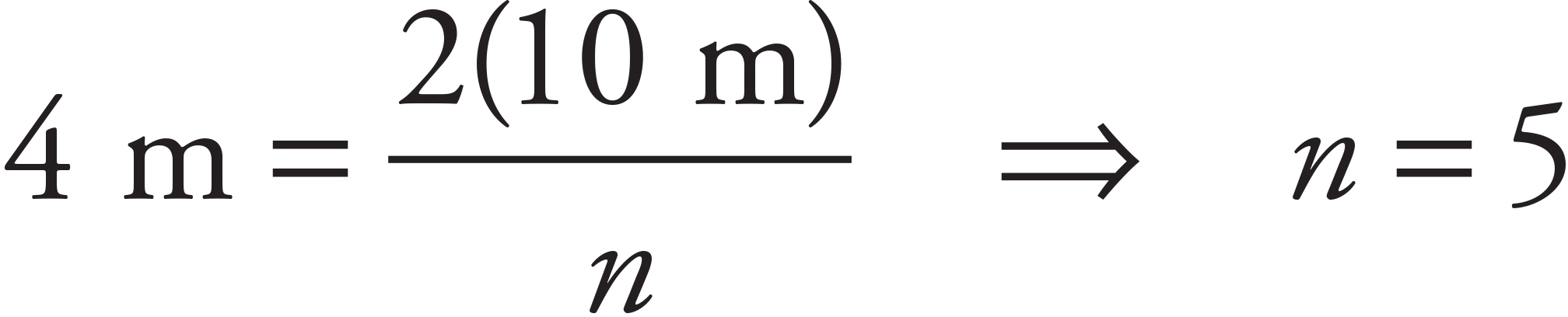

In this case, the length of the tube is equal to 3( ), so

), so

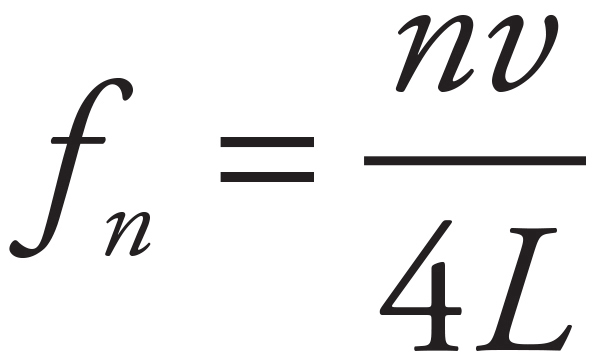

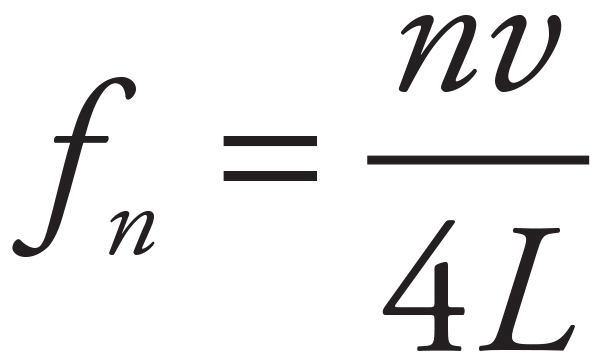

Here’s the pattern: standing sound waves can be established in a tube that’s closed at one end if the tube’s length is equal to an odd multiple of  λ. The resonant wavelengths and frequencies are given by the following equations:

λ. The resonant wavelengths and frequencies are given by the following equations:

For a Closed Tube,

If the far end of the tube is not sealed, standing waves can still be established in the tube, because sound waves can be reflected from the open air. A closed end is a displacement node, but an open end is a displacement antinode. In this case, then, the standing waves will have two displacement antinodes (at the ends of the tube), and the resonant wavelengths and frequencies will be given by

For an Open Tube,

Note that, while an open-end tube can support any harmonic, a closed-end tube can support only odd harmonics.

Example 11 A closed-end tube resonates at a fundamental frequency of 440.0 Hz. The air in the tube is at a temperature of 20°C, and it conducts sound at a speed of 343 m/s.

(a) What is the length of the tube?

(b) What is the next higher harmonic frequency?

(c) Answer the questions posed in (a) and (b) assuming that the tube were open at its far end.

Solution.

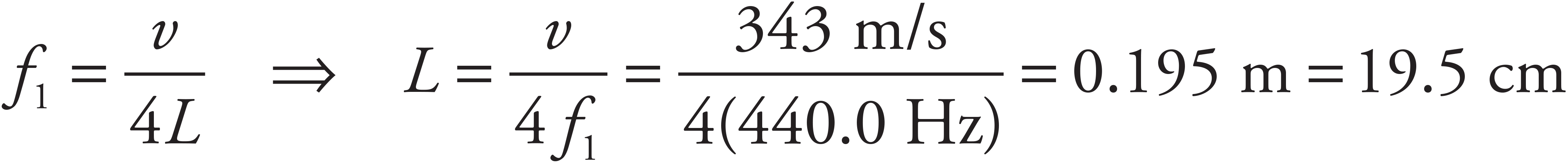

(a) For a closed-end tube, the harmonic frequencies obey the equation fn = nv/(4L). The fundamental corresponds to n = 1, so

(b) Since a closed-end tube can support only odd harmonics, the next higher harmonic frequency (the first overtone) is the third harmonic, f3, which is

3f1 = 3(440.0 Hz) = 1,320 Hz

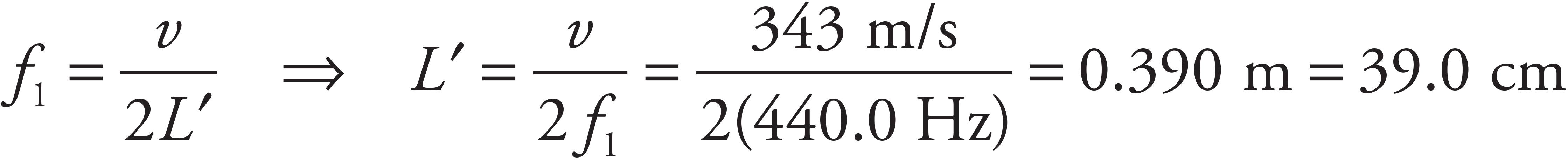

(c) For an open-end tube, the harmonic frequencies obey the equation fn = nv/(2L). The fundamental corresponds to n = 1, so

And, since an open-end tube can support any harmonic, the first overtone would be the second harmonic, f2 = 2f1 = 2(440.0 Hz) = 880.0 Hz.

When a source of sound waves and a detector are not in relative motion, the frequency that the source emits matches the frequency that the detector receives.

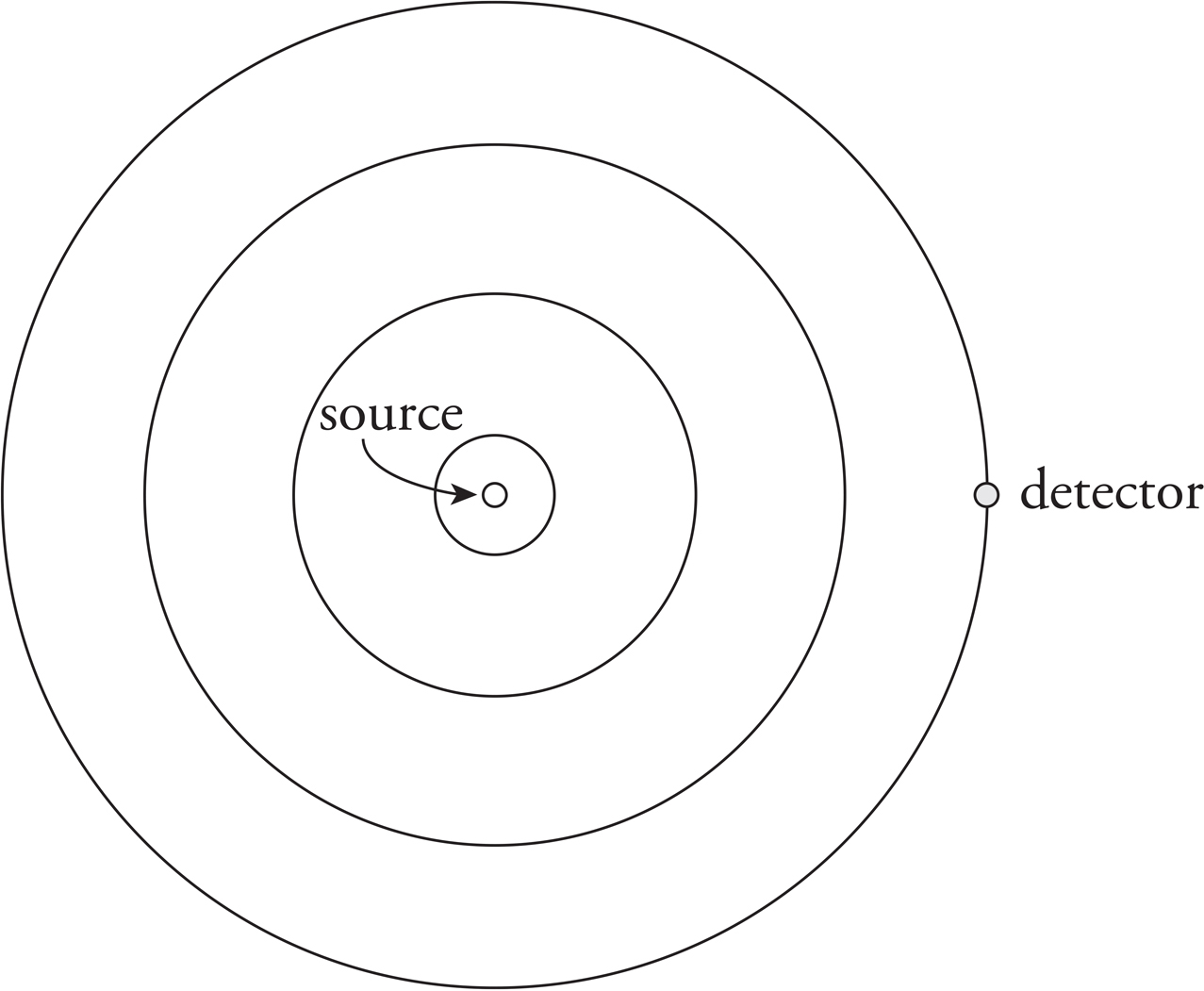

However, if there is relative motion between the source and the detector, then the waves that the detector receives are different in frequency (and wavelength). For example, if the detector moves toward the source, then the detector intercepts the waves at a rate higher than the one at which they were emitted; the detector hears a higher frequency than the source emitted. In the same way, if the source moves toward the detector, the wavefronts pile up, and this results in the detector receiving waves with shorter wavelengths and higher frequencies:

Conversely, if the detector is moving away from the source or if the source is moving away from the detector,

then the detected waves have a longer wavelength and a lower frequency than they had when they were emitted by the source. The shift in frequency and wavelength that occurs when the source and detector are in relative motion is known as the Doppler effect. In general, relative motion toward each other results in a frequency shift upward, and relative motion away from each other results in a frequency shift downward.

Answers and explanations can be found in Chapter 13.

1. What is the wavelength of a 5 Hz wave that travels with a speed of 10 m/s ?

(A) 0.25 m

(B) 0.5 m

(C) 2 m

(D) 50 m

2. A rope of length 5 m is stretched to a tension of 80 N. If its mass is 1 kg, at what speed would a 10 Hz transverse wave travel down the string?

(A) 2 m/s

(B) 5 m/s

(C) 20 m/s

(D) 200 m/s

3. A transverse wave on a long horizontal rope with a wavelength of 8 m travels at 2 m/s. At t = 0, a particular point on the rope has a vertical displacement of +A, where A is the amplitude of the wave. At what time will the vertical displacement of this same point on the rope be ‒A ?

(A) t =  s

s

(B) t =  s

s

(C) t = 2 s

(D) t = 4 s

4. A string, fixed at both ends, supports a standing wave with a total of 4 nodes. If the length of the string is 6 m, what is the wavelength of the wave?

(A) 0.67 m

(B) 1.2 m

(C) 3 m

(D) 4 m

5. A string, fixed at both ends, has a length of 6 m and supports a standing wave with a total of 4 nodes. If a transverse wave can travel at 40 m/s down the rope, what is the frequency of this standing wave?

(A) 6.7 Hz

(B) 10 Hz

(C) 20 Hz

(D) 26.7 Hz

6. A sound wave travels through a metal rod with wavelength λ and frequency f. Which of the following best describes the wave when it passes into the surrounding air?

|

|

Wavelength |

Frequency |

|

(A) |

Less than λ |

Equal to f |

|

(B) |

Less than λ |

Less than f |

|

(C) |

Greater than λ |

Equal to f |

|

(D) |

Greater than λ |

Less than f |

7. In the figure below, two speakers, S1 and S2, emit sound waves of wavelength 2 m, in phase with each other.

Let AP be the amplitude of the resulting wave at Point P, and AQ the amplitude of the resultant wave at Point Q. How does AP compare to AQ?

(A) AP < AQ

(B) Ap = AQ

(C) Ap > AQ

(D) AP < 0, AQ > 0

8. An organ pipe that’s closed at one end has a length of 17 cm. If the speed of sound through the air inside is 340 m/s, what is the pipe’s fundamental frequency?

(A) 250 Hz

(B) 500 Hz

(C) 1,000 Hz

(D) 1,500 Hz

9. A bat emits a 40 kHz “chirp” with a wavelength of 8.75 mm toward a tree and receives an echo 0.4 s later. How far is the bat from the tree?

(A) 35 m

(B) 70 m

(C) 105 m

(D) 140 m

10. Two cars starting from the same position begin driving along the same horizontal axis. If Car A’s horn emits a sound wave, which of the following pairs of velocities would result in the greatest difference between the wave’s source frequency and the perceived frequency for Car B?

|

|

Car A |

Car B |

|

(A) |

20 m/s to the right |

30 m/s to the right |

|

(B) |

10 m/s to the right |

25 m/s to the right |

|

(C) |

10 m/s to the left |

10 m/s to the right |

|

(D) |

30 m/s to the left |

30 m/s to the left |

1. A rope is stretched between two vertical supports. The points where it’s attached (P and Q) are fixed. The linear density of the rope, μ, is 0.4 kg/m, and the speed of a transverse wave on the rope is 12 m/s.

(a) What’s the tension in the rope?

(b) With what frequency must the rope vibrate to create a traveling wave with a wavelength of 2 m?

The rope can support standing waves of lengths 4 m and 3.2 m, whose harmonic numbers are consecutive integers.

(c) Find

(i) the length of the rope

(ii) the mass of the rope

(d) What is the harmonic number of the 4 m standing wave?

(e) On the diagram above, draw a sketch of the 4 m standing wave, labeling the nodes and antinodes.

2. For a physics lab experiment on the Doppler effect, students are taken to a racetrack. A car is fitted with a horn that emits a tone with a constant frequency of 500 Hz, and the goal of the experiment is for the students to observe the pitch (frequency) of the car’s horn. (Note: fD = fC (v ± vD)/(v ± vC) where fD is the wave’s frequency at the detector, fC is the wave’s frequency at the car, v is the speed of the wave, vD is the speed of the detector, and vC is the speed of the car. The choice of + or ‒ in the equation must be determined based on the relative motion of the two objects.)

(a) If the car drives at 50 m/s directly away from the students (who remain at rest), what frequency will they hear? (Note: speed of sound = 345 m/s.)

(b) Would it make a difference if the car remained stationary and the students were driven in a separate vehicle at 50 m/s away from the car?

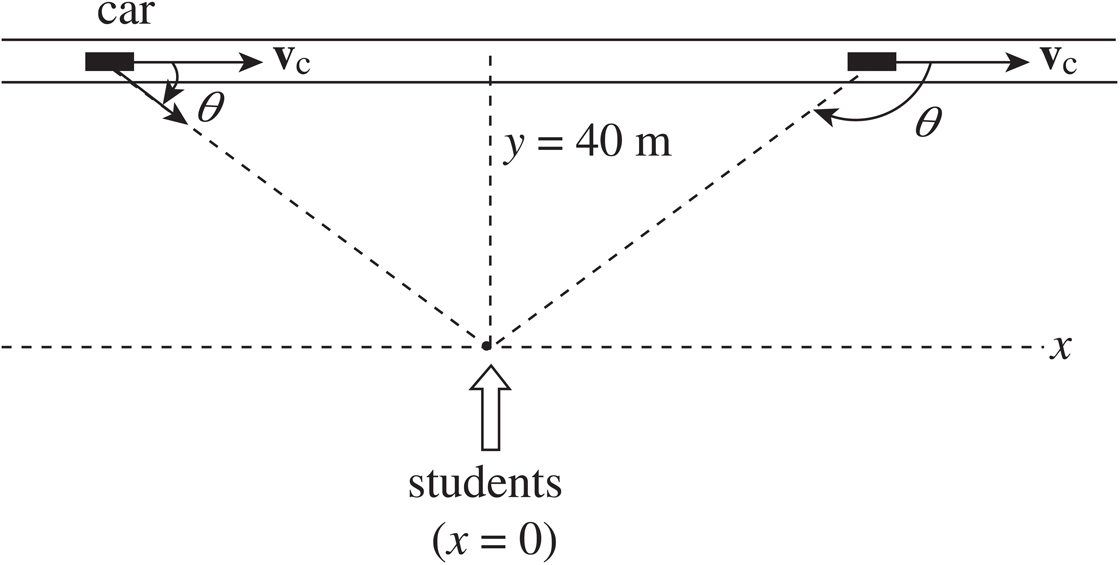

The following diagram shows a long straight track along which the car is driven. The students stand 40 m from the track.

As the car drives by, the frequency which the students hear, f′, is related to the car horn’s frequency, f, by the equation

where v is the speed of sound, vC is the speed of the car (50 m/s), and θ is the angle shown in the diagram.

(c) Find f′ when θ = 60°.

(d) Find f′ when θ = 120°.

(e) On the axes below, sketch the graph of f′ as a function of x, the horizontal position of the car relative to the students’ location.

3. A group of students perform a set of physics experiments using two tuning forks, one with a frequency of 400 Hz and the other 440 Hz.

(a) What is the observed beat frequency when the two tuning forks are struck?

(b) Describe the changes to the frequency, wavelength, and speed of the sound waves from the tuning forks as they travel from air into water.

(c) One student strikes a tuning fork and then throws it straight up to a student on the second floor of a building. What happens to the frequency of the sound that the student on the second floor hears as the tuning fork travels upward?

The speed of a wave depends on the medium through which it travels. Speed can be determined by  , where f is the frequency (

, where f is the frequency ( ) and λ is the wavelength. Because

) and λ is the wavelength. Because  , the speed can also be written

, the speed can also be written  .

.

Changing any one of the period, the frequency, or the wavelength of a wave will affect the other two quantities, but will not affect the speed as long as the medium remains the same.

If the wave travels through a stretched string, its speed can be determined by  , where FT is the tension in the spring and μ is the linear mass density (mass/length).

, where FT is the tension in the spring and μ is the linear mass density (mass/length).

Superposition is what occurs when parts of waves interact so that they constructively or destructively interfere (e.g., create larger or smaller amplitudes, respectively).

Standing waves on a string that is fixed at both ends can form with wavelengths of  and frequencies of

and frequencies of  , where L is the length of the string, v is the speed of the wave, and n is a whole positive number.

, where L is the length of the string, v is the speed of the wave, and n is a whole positive number.

If one end of the string is free to move, standing waves can form with wavelengths of  and frequencies of

and frequencies of  , where L is the length of the string, v is the speed of the wave, and n must be a positive odd integer.

, where L is the length of the string, v is the speed of the wave, and n must be a positive odd integer.

Sound is a longitudinal wave. Its speed is given by  , where B is the bulk modulus (this indicates how the medium responds to compression) and the density of air. At room temperature and at normal atmospheric pressure, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s.

, where B is the bulk modulus (this indicates how the medium responds to compression) and the density of air. At room temperature and at normal atmospheric pressure, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s.

Two waves interfering at slightly different frequencies will form a beat frequency given by  .

.

Resonance of sound in a tube depends on whether the tube is closed on one end or open on both ends. For a closed-end tube resonance occurs for  and

and  , where n must be an odd integer. For an open-end tube, resonance occurs for

, where n must be an odd integer. For an open-end tube, resonance occurs for  and

and  , where n can be any integer.

, where n can be any integer.

The Doppler effect tells you how the frequency of the sounds will vary if there is a relative motion between the source of the sound and the detector (observer). If the relative motion of the objects is toward each other, the frequency will be perceived as higher. If the relative motion is away from each other, the frequency will be perceived as lower.