Chapter 50

The Library at Monte Cassino

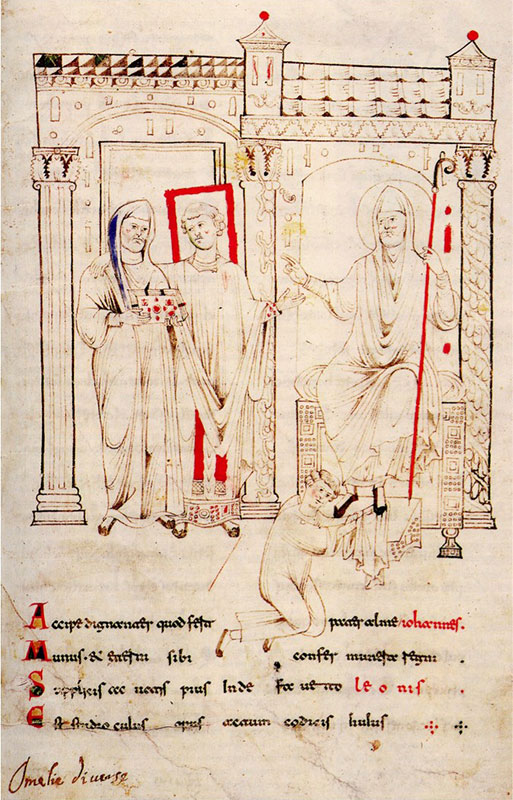

According to tradition, it was at Monte Cassino that Benedict of Nursia, founder of the monastery around the year 529, wrote the Rule for monks; in its chapter 48 he enjoined: “In quibus diebus Quadragesimae, accipiant omnes singulos codices de bibliotheca, quos per ordinem ex integro legant; qui codices in caput Quadragesimae dandi sunt” (“For these days of Lent, they are all to receive a book apiece from the library, to read in order from the start; these books are to be handed out at the beginning of Lent”). A miniature in MC 132, the Encyclopaedia of Rabanus Maurus (copied under Abbott Theobald, 1022– c.1030) would have been very likely understood in the Middle Ages as representing this Lenten distribution (Plate 50.1). It was on the foundation of this injunction that the great Benedictine monastery libraries of the Middle Ages arose, and not least that of Monte Cassino itself.

Plate 50.1 MC 132 (Theobaldan, 1022–c.1030), the famous Rabanus encyclopedia, p. 94 (NB: All Monte Cassino manuscripts are paginated and so cited in scholarly literature.). A monk draws books from a handsome book chest to distribute to two of his fellows.

Do any volumes from the library of St. Benedict’s day survive? MC 150, the so-called Ambrosiaster in Half-uncial, is the oldest manuscript preserved at the abbey today. It was read by the presbyter Donatus at Castellum Lucullanum at Naples and can be dated before ad 570. This means that this ancient monument would be approximately contemporary with Benedict himself. But, given the disasters that have befallen the monastery early and late, beginning with the Longobard invasion of c.580, it is most unlikely that this treasure has been in the possession of the abbey continuously since the sixth century; in this case the manuscript may have been brought to Monte Cassino, perhaps from Naples itself, as a gift in the Desiderian or Oderisian period (1058–1105).

The Carolingian Age

The restoration of the abbey under Abbot Petronax (c.718) laid the foundation for its flourishing culture in the Carolingian period. The most famous man of letters in Italy in this age was Paul the Deacon, author of the Historia Langobardorum, whose home was at Monte Cassino—except for a four-year stay at Charlemagne’s court (782–6)—in the last two and one-half decades of the century. Apart from the History, Paul’s works included the poetry published by Neff and his commentary on Donatus’ Ars Minor and abridgment of Festus’s De Verborum Significatu. The house that was home to this scholar will have had a very considerable library. Those who deny this forget that two factors have conspired to rob us of that library: (1) the disaster of the slaughter of abbot and monks and burning of the monastery by the Saracens in 883; and (2) the success of the monastery that rose again with the return of the monks in 950 and especially in the succeeding century and one-half, when the intense program of manuscript production meant that virtually all the older volumes would have been copied in the splendid new script and the surviving Carolingian volumes discarded.

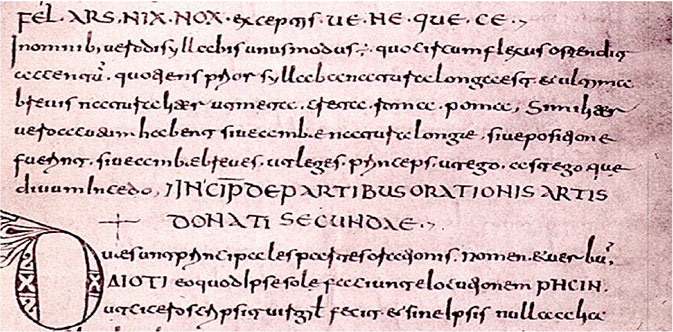

It is telling that the exceptions that do survive from the eighth and ninth centuries were either manuscripts preserved in the Middle Ages in centers other than Monte Cassino or manuscripts that had subscriptions or other historical significance and were preserved for this reason. A famous example of the former sort spent a sizable part of its medieval life at Benevento; it is now Paris, BnF, lat. 7530, datable to the decennovenal Paschal cycle 779–97 (Plate 50.2). L. Holtz (1975) calls this volume a “Cassinese synthesis of the liberal arts.” The book must reflect the learning of Paul the Deacon and the teaching carried out in the abbey’s school in the high Carolingian era. The manuscript is the only one to preserve the didascaliae to the lost Thyestes of the poet Varius, and the “Anecdoton Parisinum,” a text that transmits material from a lost work of Suetonius’, this amid a large collection of grammatical works and arithmetical and geometrical texts. The manuscript reflects a rich strain of late ancient learning compatible with Paul’s access to the text of Festus, preserved (so far as we know) only in southern Italy. Other manuscripts of Cassinese origin from the Carolingian era are Cava 3, Isidore, also datable to 779–97 by a Cassinese calendar; and perhaps Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Patr. 61, Cassiodorus, Greg. Turon., and Isidore. Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, 641, pt. 1, Alcuin and calendarial matter, dated 811–12, is clearly Cassinese.

Plate 50.2 Paris, BnF, lat. 7530 (779–97), fol. 171r. This rich collection of ancient learning presents here (after the stately late Uncial heading) Donatus on the parts of speech. Word separation is rare. The letters a (like 2 c’s), which is open, and t, which has loop to left, with loop not extending down to baseline, are characteristic of an early form of Beneventan. Ligatures are especially noticeable: æ on the baseline, ri with long swinging tail, soft ti correctly in “orationis” in line. 9, li., and gi. Especially characteristic of the early form of Beneventan are (l. 4) “te” in “naturaliter” and in particular (l. 5) “tu” in “acutum.”

The grammatical treatise of Ildericus preserved in MC 299, the work of Paul’s student by that name, was probably faithfully kept because assigned in the Middle Ages to the ninth-century Abbot Hildericus of Monte Cassino. Again, the historical bent of south Italian teachers and students—and local pride—probably accounts for the preservation of this work rich in classical citations.

In addition to the ars grammatica, scientific arts and compilations were pursued at Monte Cassino during the ninth century. MC 69, Medica, was preserved because of its association with the martyr Abbot Bertharius (856–83). But it is considered that MC 3, containing astronomical drawings, is also Bertharian. Medical treatises are also found in Florence, BML, 73.41 and MC 97, perhaps Casinenses as well.

What survives from the Cassinese library of the Carolingian era and down to the Saracen destruction of 883 reflects holdings in the artes broadly. It is immediately striking that what is missing is texts of the major Fathers, except where these may be joined in a subordinate role to those handbooks. Otherwise, patristic texts have not survived. And, if, because of the two historical causes mentioned, the disaster that destroyed the Carolingian abbey, and the subsequent brilliant development, the books of the Fathers that Paul the Deacon and Ildericus knew have not survived, it is hardly to be expected that the classical books they consulted would have come down to us.

The Period of Exile in Capua

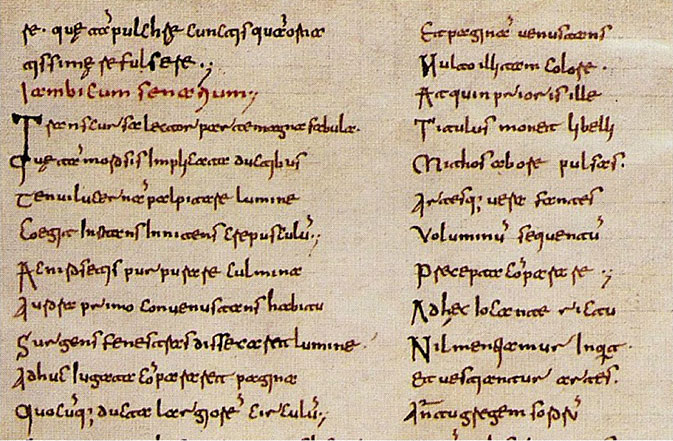

If certain manuscripts preserved at Monte Cassino today have belonged to the Cassinese community since their origin in the ninth and tenth centuries, that community’s interest in the artes continued even in exile. To this period belongs (Plate 50.3) MC 332, the De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii of Martianus Capella, of the late ninth or early tenth century; though its decoration is “poor and archaizing” (Orofino 1994–2006, vol. 1, 51), the script shows a certain finesse. The ars grammatica is represented by the glossaries MC 401 and 402, and historical/scientific interests if Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 3342, Solinus, is to be ascribed to Monte Cassino.

Plate 50.3 MC 332 (saec. IX ex./X in.), p. 37. Here verses from the end of Book 2 and the opening of Book 3 of Martianus Capella, The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. The script is a continuation of the slender variety, with tall ascenders and little or no contrast; it is the ancestor of the later Fine Script. In col. 2, l. 12, the 2-shaped sign over “An” marks the beginning of a question. Arguably, Beneventan gave more aid to the lector in reading aloud than any other medieval script, as Radding and Newton (2003) have proposed.

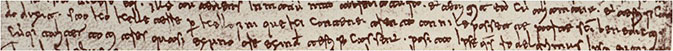

But the fresh energies and recovery of the community are strikingly shown in MC 175, dated to the abbacy of John I (914–34); this is what Dell’Omo (1999, 259) has called “a true, proper summa of the liturgical and historical traditions of Monte Cassino.” The script has entered a new stage of its development; it is not surprising that a book so deeply imbued with historical feeling and endowed with a portrait of its committente John should represent the finest script of the abbey at this moment. It was under the mid-century abbot Aligern that MC 269, Gregory the Great, Moralia—finally, a text of a major Father that is preserved—was produced by the community, still then in Capua, and therefore before 1049–50; it is the subscription that attests this. In 1050, Aligern succeeded in re-establishing the community in its home on the mountain at Casinum. Like Rocca Ianula, the fortress that Aligern built there, Monte Cassino still possesses another Aligernian monument, this one also a monument of the Italian language, the Placitum issued at Capua in 969 (Plate 50.4) containing the earliest self-conscious attestation of the volgare in its contrasting Latin context. The second half of the century sees the copying of other Gregory volumes, e. g., MC 77, signed by its scribe, and of a now lost volume of “Hegesippus”—testimony to the continued interest in history—with subscription of the committente Abbot Manso (986–96), whose reign ended tragically with his blinding by his enemies.

Plate 50.4 MC, Archivio (969): Placitum issued at Capua, 960. The document shows, embedded here, the earliest Italian phrases self-consciously inscribed in a Latin text: “sao ko kelle terre per kelle fini que ki contene trenta anni le possette parte Sancti Benedicti…”

The Golden Age: The Century of Abbots Theobald, Desiderius, and Oderisius I

Eleventh-century Monte Cassino was marked culturally by three bibliophile abbots. Theobald of Chieti, the red-haired abbot (1022 to, effectively, about 1030) had a program of book-copying already as prior of S. Liberatore alla Maiella; this is documented in his Commemoratorium of the year 1019. As abbot, Theobald clearly commanded ample resources for book production; he had his portrait entered in MC 73, another Gregory the Great, Moralia, and two other volumes (MC 28 and 57) contain lists of books he had copied; Leo Marsicanus drew on these for the list of Theobaldan books he gives in the Chronicle. Most splendid of the books listed there, and one culmination of the monastery’s series of handbooks and compilations, is the visually enchanting encyclopedia of Rabanus Maurus (today MC 132, already cited), the earliest surviving copy of this text with illustrations.

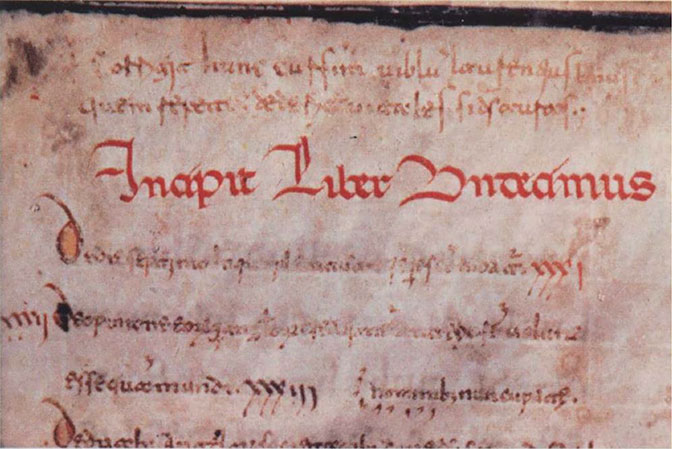

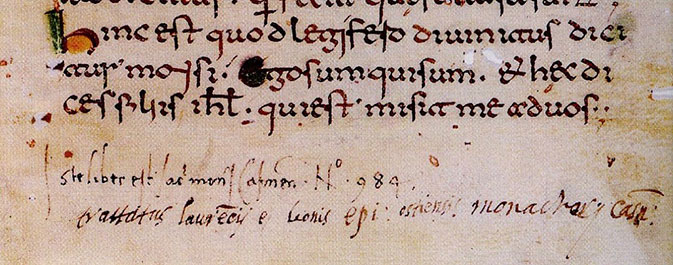

Two figures from distant points to north and south illustrate the book culture of Theobald’s house. (1) In June 1022 the German Emperor Henry II visited the abbey and arranged the election of Theobald as abbot; in gratitude for a miraculous healing that he experienced there, he presented rich gifts to St. Benedict, among them the handsome Gospel Book now Vatican City, BAV, Ottob. lat. 74, a product of St. Emmeram of Regensburg. (2) Probably in November of the same year a scholar named Leo, of Amalfi, entered the community as a monk under the name Lawrence, the name he is known by in modern literature (he was afterward archbishop of Amalfi). A bilingual polymath (his Greek Psalter with commentary survives as Vatican City, BAV, Vat. gr. 619), he served as technical corrector of the Augustine manuscript MC 28, where he signed in verse at the points at which he began and ended (Plate 50.5). He also compiled the Handbook of the Liberal Arts—the recurrent theme at Monte Cassino—surviving as Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Marc. Z. lat. 497, a manuscript in Central Italian script manifestly copied from an exemplar in Beneventan script. This volume contains a rich florilegium of excerpts from the classics, the Fathers, and early medieval texts, from Terence down to Paul the Deacon, Theodulf, and Alcuin, which must have been assembled by Lawrence himself. This continues the grammatical/stylistic studies pursued at the abbey since the eighth century. In Lawrence’s hagiographical works one can see the scholar making use of extracts from this collection. The wide reading behind the florilegium points to the richness of libraries available to Lawrence, including some exceedingly rare texts, such as the elegist Tibullus.

Plate 50.5 MC 28 (ad 1023), p. 1: Lawrence of Amalfi’s hexameter verses on correcting the MS: “+ Corrigit hunc cursim uiblum laurentius imus / Quem repetet, dederit uitales si Deus auras” (“+ Lowliest Lawrence in haste corrects this book; / A task he will resume, if God but grant him breath of life”). Below, the original scribe’s hand—a developed early eleventh-century one with very little breaking of minims—on this first page of Augustine’s City of God, Book 11.

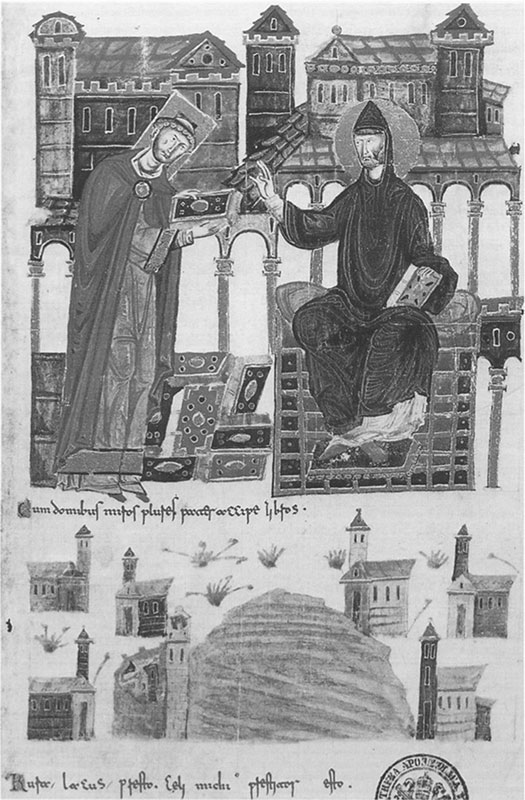

But it was under the abbots Desiderius (1058–87) and Oderisius I (1087–1105) that the apogee of book production and study was reached. The gifts of generous patrons, such as the German Empress Agnes (a Gospel Book now marked as MC 437), and especially of the new Norman rulers of southern Italy, allowed a bibliophile abbot to indulge his book-collecting and book-copying passion (studium). The lists of books preserved in the Chronicle of the abbey include only display manuscripts, or texts or forms of texts not held in the Cassinese collection before. Production was, therefore, much more extensive than the Chronicle’s attestations. At the opening of Desiderius’ rule, the master Grimoald (contrary to the traditional Theobaldan date for this scribe) produced inter alia his splendid homiliaries MC 104 and 109 (with his own portrait) and the lovely Exultet Roll, now Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 3784. Other superb scribes include the Leo who copied the lectionary MC 99 (ad 1072) with a portrait of another Leo (Leo Marsicanus, the future Chronicler, who oversaw its production), with his uncle Johannes Marsicanus (Plate 50.6). The nephew’s hand is seen in Vatican City, Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Regesti Vaticani I, the Register of John VIII, the earliest papal register to survive; and in the draft of his own Chronicle (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 4623). Another master has been called the Dialectica Scribe, after his logical texts now in Vatican City, BAV, Ottob. lat. 1406, (Plate 50.7), the most splendid classical book ever produced at Monte Cassino; it has been proposed that the volume celebrates the victory of Alberic of Monte Cassino and Desiderius over Berengar of Tours in the climax of the Eucharistic Controversy at the Rome synod of Lent 1079. The same hand produced the handsome Exultet Roll in Beneventan preserved at Pisa as Museo Nazionale di S. Matteo, s.n. (Exultet 2). In this connection, it is clear that the abbey created Exultet Rolls not only for its own use, but to serve as gifts (an example, the Exultet Roll made for Pandulf, bishop of the Marsian church, and still preserved in the Curia Vescovile at Avezzano) and to accompany Cassinese monks chosen as abbots or bishops in other centers (an example, the Exultet of Leo Marsicanus preserved at Velletri in the Archivio Capitolare s.n. [Exultet]). Another master created (Plate 50.8) the celebrated Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 1202 (to be dated to 1075), the third and culminating lectionary for the feasts of Sts. Benedict, Maur, and Scholastica—this one being rich in miniatures illustrating these texts; the texts collected here are the most intimately tied of all books to the central saints of the abbey, and the authors range in time from the eighth century down to the mid-Desiderian period. During the decade preceding this lectionary’s production, Cassinese scribes had begun to create a new style of decorated initial, based upon their own south Italian traditions and upon the strong German influence of the decoration in the Henry II Gospels. At the opening of the lectionary, the Dedication scene and its accompanying poem present a brilliant (and perhaps unmatched in the Latin Middle Ages) instance of the interplay of poetry and visual art, with its subtle “specular” relationship between Alfanus’ ode celebrating Desiderius on the left and the renowned miniature on the right, across the opening. The heap of books at Desiderius’ feet—most rare in such Dedication scenes—bespeaks the bibliophile abbot and is only part of the visual/verbal pun.

Plate 50.6 MC 99 (ad 1072), Homiliarium, p. 3. Abbot Desiderius affectionately presents to St. Benedict an older churchman, John of the Marsian church, newly received into the Monte Cassino community. John offers to the saint the book of homilies at the head of which the miniature stands. The verses proclaim that the master scribe of the manuscript was named Leo (his was the labor), and that another monk Leo (he was John’s brilliant young nephew and the future Chronicler of the abbey), depicted kneeling at the saint’s feet with the book’s manutergium or book cloth in his hands, had supervised (his was the studium) the book’s production. There is deliberate “specular” parallelism between the faces of John and the saint, and between the monastic habit that John assumes on this day and the rich cloth that young Leo provides for the book; Father Benedict receives, so wrapped, the life that is offered him, and the book.

Plate 50.7 Vatican City, BAV, Ottob. lat. 1406 (ad 1079 or slightly later), logical texts, fol. 1r. Lady Dialectica, enthroned with her traditional serpent, awards a garland of victory to one of her young protégés before her. Radding and Newton (2003, 109–13) propose that the manuscript, the most elaborate and richest classical manuscript ever produced at Monte Cassino, celebrated Alberic of Monte Cassino’s and Desiderius’ victory in the debate over the Eucharistic Controversy (ended at the Roman Synod, February 1079 with defeat of Berengar of Tours and his doctrine.)

Plate 50.8 Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 1202 (ad 1075), Lectionary for the Feasts of Sts. Benedict, Maur, and Scholastica, fol. 2r. In the year of the dedication of the two tower churches and the chapel of St. Bartholomew (depicted in the upper right background behind St. Benedict, with the great basilica and atrium, already dedicated in 1071, at upper left behind Abbot Desiderius), Abbot Desiderius presents this lectionary and the buildings as offerings to St. Benedict, seated with the Rule on his knee. The dedicatory poem (beginning of col. 1 on 1v) begins with Benedict’s founding of the monastery and ends (col. 2) with Desiderius’ fulfillment of the promise made to Benedict of its greatness. So the opening 1v–2r moves from the sixth-century founding and promise (col. 1) to the eleventh-century fulfillment (col. 2) and in the facing page mirroring movement from Desiderius (on the left) in his glory to the founder and originator (on the right—a specular effect). The ode and painting mirror each other in other, more complex ways, with verbal/visual plays and allusion across the gutter.

The Monte Cassino monks of the era remembered that the classical Roman polymath Varro (a primary source for Augustine) had owned a villa at Casinum; the Cassinese hagiographer Guaiferius echoed Cicero and saw his monastic home as a recreation of the villa of the Roman aristocrat, where the Pax Romana, now a Pax Benedictina, made possible study and the pursuit of eloquence. The literary production of the Desiderian and Oderisian period is widely varied; we may survey some of the works and some of the contemporary manuscripts that preserve them. Abbot Desiderius himself, in imitation of Gregory the Great, composed his own Dialogues (Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 1203). Desiderius’ close friend and admirer, Alfanus, archbishop of Salerno, wrote his own hagiographical works in prose, and poetry in a true classical spirit more subtly Horatian than any poet of the age (MC 280). Alfanus’ translation of Nemesius’ Peri Physeos Anthropou was not preserved in Italy, and survives complete in only one manuscript now Paris, BnF, lat. 15078, saec. xii in. The saints’ lives of the just-quoted Guaiferius, also of Salerno, bear a striking array of classical spolia (preserved in the contemporary manuscript MC 280, with Alfanus). Alberic the grammaticus (as Leo’s calendar calls him) wrote a series of hagiographical texts, many only recently identified (e.g., a manuscript of Benevento provenance, Monte Cassino, Archivio Privato, Cod. I, containing a saint’s life that the young grammaticus wrote at the tender age of 14). The libellus in which Alberic refuted the teaching of Berengar of Tours on the Eucharist has recently been identified (Radding and Newton 2003) in the late eleventh-century Aberdeen, University Library, MS 106. The same master’s rhetorical works included the earliest stage of teaching of dictamen (no manuscripts survive in Italy). Leo Marsicanus’ Chronicle has been mentioned (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 4623). In that field, contemporary history was also written; Amatus’ Historia Normannorum does not survive in Latin, but the Old French version is preserved in Paris, BnF, fr. 688. Cassinese interest in the artes continued. Among the books produced in the scriptorium in this period was the remarkably valuable collection of texts on music and musical theory still shelved at the abbey (MC 318). The long fascination with scientific works is unbroken. Pandulf of Capua’s little treatise on the abacus, with its newly imported Hindu-Arabic numerals and the earliest European manuscript depiction of a scholar using them on the abacus, survives, alongside grammatical treatises of Alberic, in a single copy (Vatican City, BAV, Ottob. lat. 1354, of the late eleventh or early twelfth century). Most striking of all is the exotic figure of Constantinus Africanus (that is, “of Ifriqiyah,” slightly larger than the area of modern Tunisia). Of the 25–30 translations or adaptations of Arabic medical treatises under his name, his masterwork, the Pantegni, “The Universal Art [of Medicine],” is dedicated to Abbot Desiderius, and therefore dated before the abbot’s assumption of the papal title in 1086 (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 73 J 6, in ordinary minuscule but from Monte Cassino).

It is with the Desiderian age that the great series of surviving patristic texts appear, headed by Augustine; a veritable campaign led to the assembling of a total of some 29 Augustinian volumes in this period. Most valuable textually are the volumes of Augustine’s sermons (especially MC 17) that transmit the didascaliae—information on when and where the sermons were preached. The authentic form of Eugippius’ Augustinian handbook is preserved uniquely in a Desiderian manuscript (MC 13), as is the Expositio libri Iob (MC 371) of Augustine’s opponent, Julian of Eclano; another rare text, Hegemonius’ Acta Archelai, is preserved in the latter manuscript also. We would not have Hilary’s hymns and his Liber mysteriorum if the early Desiderian manuscript (Arezzo, Biblioteca della Città, 405) had not preserved them. The same manuscript is the unique witness to the Peregrinatio Egeriae, immensely valuable for the light it throws both upon early Church liturgy and upon Vulgar Latin. The MC manuscript 204 contains the only complete Latin text of the Passio of Perpetua and her fellow martyrs. MC 173 uniquely preserves the correct text of a sermon of Quodvultdeus, bishop of Carthage. The presence of a number of rare or unique African texts suggests that the Desiderian and Oderisian scribes had access to a pool of books brought to southern Italy by refugees displaced by the Vandal Invasion. The manuscript of the later, exceedingly rare Iohannis of Corippus listed in the Desiderian catalogue is now lost.

In his evocation of the great classics, Amatus, by subtle allusion to Horace’s Odes, in effect compares the authors to Roman gods, Cicero being the Jupiter among them. This respect is clearer than ever today. Guaiferius’ work is splendidly enriched, as Leighton Reynolds (1968) and his successors (e.g., Newton 1999, 96 and 289–90) have shown, by allusions to (among others) Cicero, Seneca—the first time these texts of Seneca had been cited in five hundred years—and the inscription on the arch of Constantine in Rome. The efflorescence of classical manuscripts is stunning. From the early Desiderian period come the unique Tacitus, Annales XI–XVI and Historiae (Florence, BML, 68.2; the Tacitus was formerly dated before Desiderius’ rule, but the evidence supports instead a date in the first half of his era) and the Apuleius, Metamorphoses and Florida (a separate manuscript bound in the same volume), the somewhat later Seneca, Dialogi (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, C 90 inf.), the unique Oderisian Varro, De Lingua Latina, and, with it, the rare Cicero, Pro Cluentio (both texts in Florence, BML, 50.10). The same hand as in the Tacitus is seen in MC 71, Gregory the Great, Register; and that of the Apuleius in Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. Kgl. S. 1653 4o, a fascinating collection of gynecological texts. It can now be asserted that the Bodleian Juvenal with the otherwise unattested “Winstedt Lines” in Satire 6 found only in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canon. Class. lat. 41 of this period originated at Monte Cassino. The Eton reader (the earliest example of this sequence of Vergil; the Ecloga Theoduli; Maximianus, Elegiae; Statius, Achilleis; Ovid, Remedia Amoris and Heroides; and Arator) is Desiderian (Eton, College Library, 150). The scriptorium also produced the earliest illustrated ancient history text (Orosius in Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 3340, a Monte Cassino product); and the earliest illustrated Ovid, Metamorphoses (Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, IV F 3), which is also a valuable textual resource for the editor, was a gift to the monastery in this period.

The Later Period

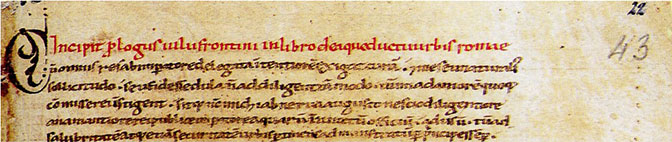

At the opening of the twelfth century Alberic’s pupil the hagiographer John of Gaeta (d.1119) continued his teacher’s work in the study of prose style; he became pope as Gelasius II. Theology was the subject of Abbot Bruno of Monte Cassino, later bishop of Segni (1107–1111). But the century is dominated by the intriguing figure Peter the Deacon, self-described “cartularius, scriniarius, ac bibliothecarius” of the abbey. Apart from his role in continuing the search for rare texts—it is his hand that copied in MC 361 (Plate 50.9) the De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae of Frontinus, on which alone the tradition rests—Peter continued the abbey’s Chronicle inherited from Leo and the shadowy Guido. Peter was a weaver of hagiographical tall tales and a forger of pious documents, but at the same time it is he who has preserved, alongside the fanciful, many of the facts about the authors of Monte Cassino.

Plate 50.9 MC 361 (saec. XII2), p. 43. Peter the Deacon’s hand, which has preserved here the ancestor of all other manuscripts of Frontinus’ treatise On the Aqueducts of the City of Rome.

The copying of manuscripts continues, even in Beneventan script, through the thirteenth century and attests a persistent interest in the classics at the abbey; a copy of the Desiderian Apuleius (Florence, BML, 68.2) was made in thirteenth-century Beneventan and survives in the same library with it today (it is Florence, BML, 29.2). As the present-day home of these manuscripts attests, this last of the Beneventan classics of Monte Cassino is close to the age when many of the abbey’s books were to be carried off by figures like Zanobi da Strada to cities and communes that were becoming the centers of humanistic learning. In addition, the monks who were guardians of the long tradition were called upon to suffer yet another disastrous destruction, that of the earthquake of 1349.

This survey concludes with brief mention of three critical eras in the subsequent history of the archive of manuscripts and documents of Monte Cassino from the Early Modern period. It was under Pope Paul II (1465–471) that a catalogue (preserved in Vatican City, BAV, Vat. lat. 3961) of the monastery’s library holdings was drawn up; and some half a century later that an ex libris was entered on the first page of each manuscript (Plate 50.10). The last two archivists of the eighteenth century, the brothers Placido and Giovanni Battista Federici, laid the foundation of a modern catalogue of the manuscripts. Their handwritten Catalogus Codicum Manuscriptorum inspired the nineteenth-century published volumes of the Bibliotheca Casinensis (1873–94), and Inguanez’ Codicum Casinensium Manuscriptorum Catalogus (1915–41). For a catalogue of the documents of the abbey, the twentieth century also brought the publication of I Regesti dell’Archivio of Leccisotti (1964–77) co-authored by Avagliano from 1974 onward. Alongside these, the monumental volumes of Giulia Orofino (1994–2006) document and illustrate the wealth of art in its manuscripts.

Plate 50.10 MC 413 (Desiderian; ex libris saec. XVI), p. 1. The manuscript, of the early Desiderian period, preserves Lawrence of Amalfi’s Life of St. Wenceslaus (beginning on this page) and other hagiographical works. At the foot stands the sixteenth-century ex libris of the monastery: “Iste liber est sacri monasterii Casinensis numero 984,” followed by a still later summary of contents.

It was the twentieth century that brought the written treasure of the abbey into peril once again (the four destructions are depicted on the modern parts of the basilica’s bronze doors). In autumn 1943 provident arrangements made by the German officers Captain Becker and Colonel Schlegel and by Abbot Gregorio Diamare removed manuscripts and documents—with other treasure—out of harm’s way, taking them first to Subiaco and then to Rome and the Vatican; and so they survived the Allied bombing of February 1944 and could be repatriated after its rebuilding; the evacuation of the treasures is well documented by the photographers attached to the German units.

To return to valuable texts, the last few years have brought fresh discoveries. R. Gyug (1990) has discovered, in the “Compactiones” or binding fragments at the abbey, part of a hitherto unknown liturgical roll in Beneventan script. Radding and Ciaralli (2007, 86–7 and 247) have suggested, with great probability, that leaves of Justinian’s Code in Beneventan (Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, Carte Vallicelliane XIII, 3) are in the style of the early Desiderian scriptorium. The text has the integral or non-epitomized form of the Code, and this volume in its entirety would have been a magnificent monument and fully worthy of the bibliophile passion of Abbot Desiderius. The most recent discovery is the identification of the fair copy of Constantinus Africanus’ Pantegni (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 73 J 6), as produced at Monte Cassino in the late Desiderian period; it bears clear marks of having been revised under the supervision of the translator. Even today, scholars in widely different fields continue to draw treasures out of medieval Monte Cassino’s book chest.