CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER TEN

DISTANT ECHOES

THE SCOPES legend notwithstanding, fundamentalism had not died in Dayton—and its adherents soon reentered the political fray with many of the same concerns as their spiritual forebears of the twenties. The political landscape, however, had changed; by the late twentieth century, Americans had come to accept many of the basic notions of individual liberty championed by the ACLU during its early years. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the U.S. Supreme Court engrafted the ACLU view of free speech, due process, and equal protection onto the Constitution. American colleges and universities widely subscribed to the AAUP’s definition of academic freedom. New Deal Congresses had enacted labor laws fully as protective of workers as those sought by Baldwin, Hays, and other ACLU founders. These legal developments made antievolution statutes seem virtually un-American by the 1960s, and led fundamentalists to seek other avenues of recourse against Darwinian teaching. Equal protection for their ideas appeared more appropriate to some fundamentalists than censoring their opponents. Furthermore, a generally acknowledged breakdown of traditional Protestant values within public education and American society left them more concerned about including creationist theories in the school curriculum than excluding evolutionary concepts from it. Their freedom and America’s future demanded no less, so they thought; yet modern concepts of individual liberty made the public increasingly wary of efforts to impose religious-based rules on Americans generally. Clashes were inevitable, and recurrent.

The developing Scopes legend left antievolution statutes particularly vulnerable by the 1960s. Those laws seemed peculiar enough in the 1920s, when Bryan offered them as a means both to preserve public morality from the alleged threat of Social Darwinism and to restore neutrality on the religiously sensitive topic of human origins by teaching nothing about it. According to the Scopes legend, however, the statutes resulted from a Quixotic crusade by fundamentalists to establish their narrow religious doctrines in the classroom. Even Bryan would have regarded such an objective with concern; certainly the Warren Court that reigned in Washington would do so as well, if given the chance. The major challenge for opponents was getting the High Court to review the old statutes. Changes in American civil liberties law during the intervening forty years had all but assured their unconstitutionality.

The United States Constitution does not say much about state restrictions on individual liberty beyond the Fourteenth Amendment bar against states depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” With respect to this clause, liberals of the 1920s worried mainly about conservative federal judges using it to strike down state economic regulations designed to protect workers, such as by minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws. This placed the ACLU in an awkward position when it sought to use the same clause to prevent Tennessee from imposing conditions on Scopes’s employment. Taking a broad view of the matter, the liberal New Republic asked in 1925, “Why should the Civil Liberties Union have consented to charge the State of Tennessee with disobeying the Constitution in order legally to exonerate Mr. Scopes? They should have participated in the case, if at all, for the purpose of fastening the responsibility for vindicating Mr. Scopes, not on the Supreme Court of the United States, but on the legislature and people of Tennessee.”1 Longtime ACLU supporter Walter Lippmann took a similar position in scoring the Scopes defense. Sensitivity to this issue influenced the way in which Hays invoked the due process clause in Dayton—always stressing that it barred patently unreasonable state laws rather than those that violated any specific individual right, even freedom of speech or the establishment of religion, lest it provide authority for courts to use property rights to strike statutes.

By the 1960s, however, federal courts had long since stopped using the Fourteenth Amendment to strike down progressive state economic regulations and instead used it to void repressive state social legislation. The process began the same year as the Scopes trial, when the Supreme Court first ruled that the “liberty” protected from state infringement by the due process clause incorporated the First Amendment right of free speech. It took more than twenty years before the High Court added the establishment clause to the rights incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment. Once it did, the Court quickly began purging well-entrenched religious practices and influences from state-supported schools. Justice Hugo Black had championed the complete incorporation of the federal Bill of Rights into the Fourteenth Amendment since his appointment to the Supreme Court during the height of New Deal disputes over the constitutionality of federal economic legislation, and later he took the lead in applying the establishment clause to public education. In 1948, Black wrote the initial decision barring religious instruction in public schools. Fourteen years later, he added the landmark opinion outlawing school prayer. In 1963, he joined in barring compulsory Bible reading from the classroom.2 These rulings finally provided solid authority for effectively challenging antievolution statutes under the federal Constitution. The Scopes legend did the rest.

The role of science in American education also changed during this period. Cold war fears that the United States had fallen behind the Soviet Union in technology led the Congress to pass the 1958 National Defense Education Act, which pumped money into science literacy programs and encouraged the National Science Foundation to fund development of state-of-the-art science textbooks. Freed from market considerations, a team of scientists and educators working under the auspices of the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) produced a series of new high school biology texts that stressed evolutionary concepts. Commercial publishers rushed to keep pace. Despite scattered protests by fundamentalists, school districts throughout the country adopted the BSCS textbooks—even in the three southern states with antievolution laws.3 No prosecutions resulted, but the new books caused some teachers to question the old laws—a few of whom took their questions to court by filing civil actions challenging the constitutionality of state laws against teaching evolution.

Two of these lawsuits played decisive roles in overturning the antievolution statutes. One began in Arkansas shortly after the Little Rock public schools adopted new textbooks in 1965. It challenged the constitutionality of that state’s antievolution law, which Arkansas voters adopted by popular referendum in the wake of the Scopes trial but which local prosecutors never enforced. The state teachers’ organization instituted this action, and a young biology instructor named Susan Epperson served as the nominal plaintiff. The Arkansas attorney general personally argued the state’s case at trial, vainly attempting to present the statute as reasonable. He questioned the theory of human evolution by noting, among other things, that anthropologists during the preceding decade had exposed the Piltdown fossils as an elaborate hoax. Limiting the issue to Epperson’s freedom to teach about various theories of origins, and cutting off specific testimony regarding any one of them, the trial judge promptly overturned the statute on federal constitutional grounds. In Tennessee a year later, Gary L. Scott threatened to challenge his state’s antievolution law after losing his temporary teaching post for reportedly telling students that the Bible was “a bunch of fairy tales.” His case generated headlines because it arose just as the Tennessee legislature again wrestled with repealing that law. Proponents of repeal compared Scott to Scopes as fellow victims of the statute. Indeed, the media referred to both cases as “Scopes II,” and John Scopes, who recently had reemerged from obscurity after publishing his memoirs, spoke out in support of both Epperson and Scott.4

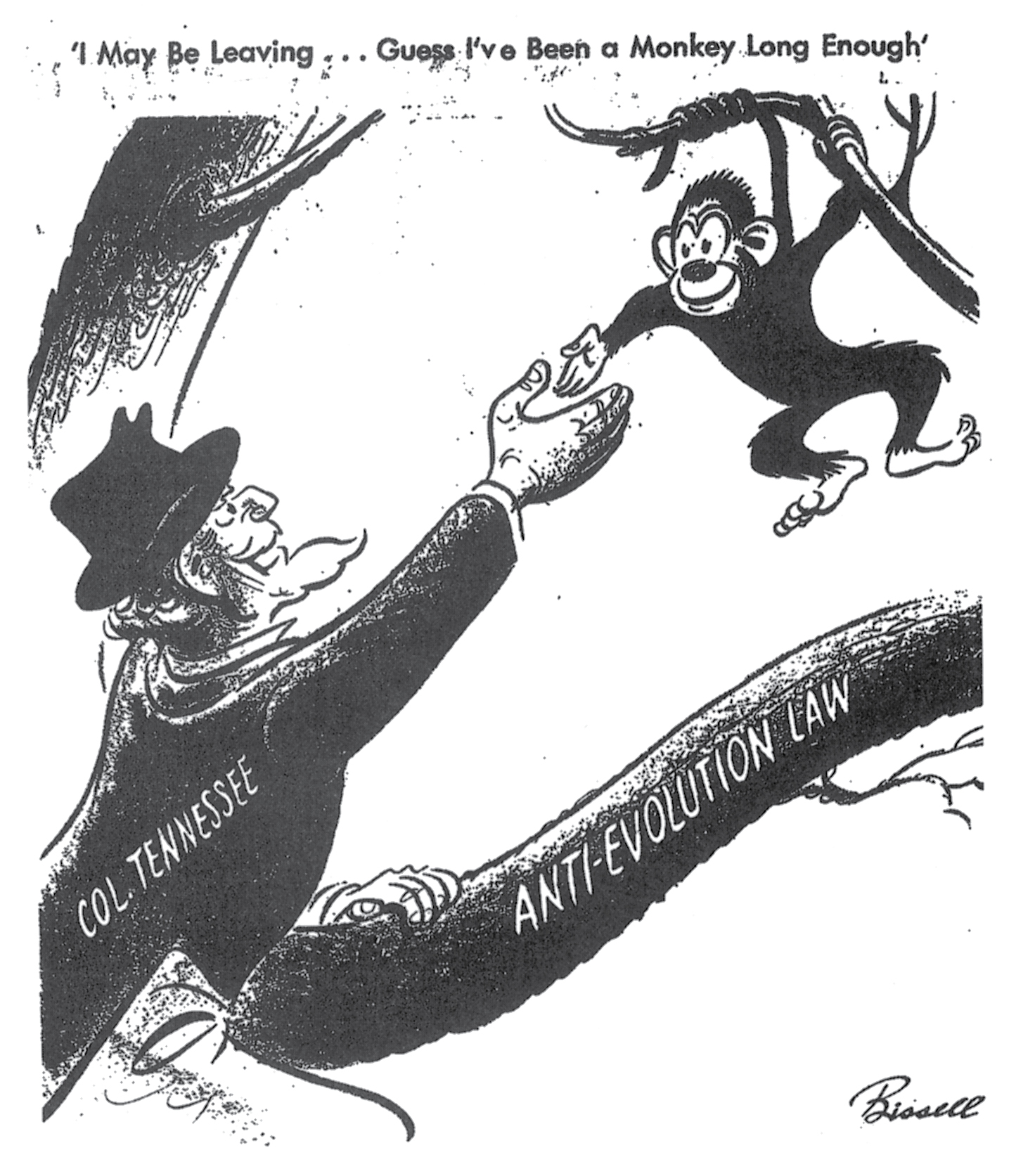

“I am going to review John Thomas Scopes’s book,” the associate editor of the Memphis Press-Scimitar told his boss early in 1967, “and I’d like to do it in a way that will stir up interest in getting the 42-year-old ‘monkey law’ repealed.” The editor-in-chief agreed, and suddenly the media spotlight shifted onto the Tennessee legislature. A series of editorials and articles critical of the law ensued. Editorialists throughout the state rallied behind legislation offered by Memphis lawmakers that, as one sponsor promised, “would remove the tag ‘Monkey State’ from Tennessee and allow evolution to be taught.”5 The Nashville Tennessean tracked the bill’s progress in a series of editorial cartoons showing “Col. Tennessee” in a monkey’s tree, contemplating whether to climb down. The national media picked up the story, which fit neatly into the popular image of a New South trying to shed its benighted past. Fitting this image, some papers noted, the Tennessee legislature now included a few African Americans (due to federal civil rights legislation) and more urban members (as a result of reapportionment ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court). “It’s been a long fight for the people of Tennessee,” Scopes told reporters. “I think the people there realized that it was a bad law and would have to be repealed sooner or later. I suppose the time has come.”6

“The upshot of the Press-Scimitar’s campaign,” the newspaper’s owners later boasted, “was that exactly two months to the day after it started, the Tennessee legislature repealed the ‘monkey law.’”7 The lower house acted first, passing the bill by a two-to-one majority. A caged monkey bearing the sixties-era sign, “Hello Daddy-o,” participated in the proceedings on the house floor. A few representatives spoke out against repeal, one of them telling his colleagues, “I’ve learned long ago if you try to conform to others, you will not be yourself. I care not what others say.” Yet most simply wanted to free their state from any legacy of the Scopes trial. “I may be leaving,” Col. Tennessee told the monkey in the next Tennessean cartoon. “Guess I’ve been a monkey long enough.”8

The three national television networks sent camera crews to broadcast the “historic” senate vote to repeal the antievolution law. Instead, as one reporter described the scene, “The debate bogged down in public professions of faith and little discussion of the merits of the bill,” ending in a sixteen-to-sixteen deadlock that temporarily preserved the status quo. “Oh, America, America,” one opponent of repeal declared during the debate, “I’m a sinner and proud to testify that I believe the very word of God.” A proponent countered, “I reread the Book of Genesis this morning and I do not find any conflict between Darwin’s theory and the Bible.” Excerpts from the debate appeared on the television news along with clips from Inherit the Wind. “Seems I’m still here,” Col. Tennessee greeted the monkey in the next morning’s paper, “Have a nut?”9

Opponents of the law now used Scott’s threatened lawsuit, Scopes II, to pressure the senate. The national ACLU offered its assistance, as did famed defense attorney William M. Kunstler—a latter-day Clarence Darrow. Sixty Tennessee teachers and the National Science Teachers’ Association joined as co-plaintiffs when Scott filed his challenge to the antievolution statute in federal court on May 15, 1967. “Nobody is asking any legislator to sacrifice any personal religious convictions by taking this law off the books,” the Tennessean commented in its lead editorial that day. “Repeal simply means… that Tennessee would be saved the ordeal of another trial in which a proud state is required to make a monkey of itself in a court of law.” Senators capitulated the next day. With network news cameras again in the chamber, they voted without debate to repeal the law. Scopes hailed the action, but one national correspondent reported “mixed feeling in Dayton about the matter.” Several townspeople expressed support for the old law. “Evolution should be taught as a theory,” former Scopes trial witness Harry Shelton now conceded. “Teaching it as a fact, however, is a different matter.”10

local editorial cartoon commenting on legislative efforts to repeal the Tennessee antievolution law in 1967. (Copyrighted by the Tennessean, April 15, 1967. Reprinted with permission)

Two weeks later, the legal issue sprang to life anew when the Arkansas Supreme Court reversed the trial judge’s ruling in the Epperson case. The court did not hear oral arguments in the case or issue a formal written opinion. It simply upheld the Scopes-era law as “a valid exercise of the state’s power to specify the curriculum in its public schools,” and added that it “expresses no opinion on the question of whether the Act prohibits any explanation of the theory of evolution or merely prohibits teaching that theory as true.”11 The forces that had rallied around Scott now threw their support behind Epperson’s further appeal. Four decades after the Scopes ruling, the ACLU finally had a decision that it could appeal to the United States Supreme Court. “The fact that the appeal now will have to be carried forward from Arkansas—rather than from Tennessee where the nonsense all started—will be readily productive of the kind of headlines that almost everybody in Arkansas seems to deplore,” one Little Rock newspaper complained.12 Before the High Court could hear the merits of the case, however, the justices had to decide to accept the appeal. Again, the Scopes legacy proved decisive.

Justice Abe Fortas took up Epperson’s cause behind the scenes at the Supreme Court. After receiving the plaintiffs’ petition, his young law clerk, Peter L. Zimroth, advised Fortas to “dismiss and deny” the appeal because, as the clerk wrote in a memo, “This case is simply too unreal.” Zimroth explained that the statute may not bar teaching about evolution and, if it did, then prosecutors never threatened to enforce it. “Unfortunately, this case is not the proper vehicle for the Court to elevate the monkey to his proper position,” he concluded. Fortas had other ideas. “Peter, maybe you’re right—but I’d rather see us knock this out,” he scrawled across the memo, “I’d grant or get a response.” The Court went along with Fortas insofar as asking the state to respond. Arkansas’s new progressive attorney general, Joseph Purcell, who had taken office since Epperson’s original trial, had no special interest in the old law. He filed a perfunctory answer that did little more than assert that the statute constituted a valid exercise of state authority. “The response is as outrageous as the law which it seeks to defend,” Zimroth now advised Fortas. “With you, I would like very much to strike the law down. However, I think the problems raised in my original memo are substantial.…” After crossing out the last phrase, he simply concluded, “I would still recommend that the court dismiss and deny.” Fortas held firm, however, and the Court agreed to hear the case.13

The resolve of Fortas to hear the appeal probably sprang from his special interest in the Scopes case, which he experienced almost firsthand as a Tennessee public high school student during the mid-1920s. The fundamentalist–modernist controversy had swirled about him as a working-class Jewish boy growing up in the Baptist citadel of Memphis. This background certainly entered his thoughts as he considered the Epperson appeal, because his files for the case include a reply from an old friend to whom he had written about the case: “Now that the decision has been made, I should like to have a chance some day to review some of the arguments made in Breckenridge High School in 1925,” the friend reminisced. “They dealt mostly with [biblical] Higher Criticism.” Fortas left Tennessee for a career resembling that of Arthur Garfield Hays—including an Ivy League legal education, government service, a lucrative East Coast corporate law practice, and close ties to the ACLU in defending civil rights and liberties. Fortas dearly wanted to decide the Epperson case, and did so as one of his last majority opinions before a financial scandal forced him from the bench.14

Echoes of the Scopes trial resounded throughout Epperson’s appeal before the Supreme Court. At the outset, Justice John M. Harlan’s law clerk warned in an internal memorandum, “One objective of the Court should be to avoid a circus à la Scopes over this.” Yet participants could hardly refrain from drawing analogies to that legendary case. The plaintiffs’ principal brief to the Court closed with a dramatic reference to “the famous Scopes case” in Tennessee, and the “darkness in that jurisdiction” that followed it. The state opened its plodding written reply by appealing to the authority of the Scopes decision and closed it with extended excerpts from the Tennessee Supreme Court opinion in that case. The ACLU brief began, “The Union, having been intimately associated with Scopes v. Tennessee 40 years ago, when this issue first arose in the courts, looks forward to its final resolution in this case.” Allusions to the Scopes case ran through the oral arguments and media coverage as well.15

When the justices met to discuss the case two days after oral arguments, all except Hugo Black voted to strike the law. Based on personal experience, Fortas viewed the law as an unconstitutional establishment of religion and asked the court to overturn it on that basis. According to Fortas’s notes of that conference, however, most of his colleagues viewed the law as void for vagueness. “Act is too vague to stand,” Chief Justice Earl Warren reportedly observed. “State has shown no need for the Act. When they prohibit teaching a doctrine, they ought to show need in terms of public order or welfare, etc.” Bryan had offered such arguments long ago, as implausible as they might seem in the 1960s, but the Arkansas attorney general raised none of them. Justice William O. Douglas agreed with the chief, adding that “establishment of religion is not really in the case,” presumably because all prior establishment clause rulings involved governmental actions that had the primary effect of advancing religion. Here the statute had little impact, if any. Only Harlan gave it a current effect by saying that “the law is a threat,” while Black countered, “There’s no case or controversy here.” No one—not even Epperson’s counsel under close questioning by Black during oral argument—suggested that it actually advanced religion in Arkansas. Almost alone, Fortas argued to “reverse on establishment grounds,” and asked to write the Court’s opinion.16

In the resulting opinion, Fortas set the Court’s holding squarely in the context of the Scopes case, beginning and ending with references to it. He conceded that the Arkansas statute “is presently more a curiosity than a vital fact of life,” yet held that it violated the establishment clause due to its original purpose. “Its antecedent, Tennessee’s ‘monkey law,’ candidly stated its purpose,” he wrote, “to make it unlawful ‘to teach any theory that denies the story of Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.’” Never mind that this language did not appear in the Arkansas statute, he adjudged, the Tennessee law was equally on trial now. To support his analysis of the statute’s historical purpose, Fortas cited the memoirs of Darrow and Scopes, a book by Richard Hofstadter, and a thirty-year-old pamphlet by the ACLU—all of which dealt with the Scopes trial rather than the Arkansas statute. Religious purpose alone became the Court’s basis for striking the law.17

Largely as a result of the Epperson decision, having “a secular legislative purpose” became a separate test for establishment clause violations, reflecting Fortas’s conviction that the clause simply must cover the Scopes situation. “In my view,” the constitutional law expert Gerald Gunther later observed, “the controversy about the [Scopes] trial planted seeds of critical analysis of statutes like the Monkey Law—seeds which, decades later, bore fruit in the Supreme Court on different grounds.” In a more general observation, senior legal scholar Charles Alan Wright added, “Darrow made Bryan look so foolish, as we have seen in various dramatizations of the trial, that it made the whole creationist position look foolish and made it much harder for people to insist that only creationism be taught.”18

Justice Black could scarcely contain his frustration over the outcome of the Epperson case. In a sharply worded separate opinion, he restated his long-standing opposition to striking statutes on account of their supposed purpose. “It is simply too difficult to determine what those motives were,” Black wrote. Drawing on personal experience as an Alabama politician during the antievolution crusade, the 82-year-old justice suggested an alternative purpose for the Arkansas law. Rather than favoring religious creationism, he wrote in Bryanesque fashion, “It may be instead that the people’s motive was merely that it would be best to remove this controversial subject [of origins] from its schools.”19 In an apparent reply to Black, Fortas added to a later draft of his opinion the Darrowlike comment, “Arkansas’ law cannot be defended as an act of religious neutrality.… The law’s effort was confined to an attempt to blot out a particular theory because of its supposed conflict with the Biblical account, literally read.”20 Forty-three years after the Scopes trial, Black and Fortas here replayed one aspect of the debate between Bryan and Darrow—yet this time, the Darrow position clearly prevailed.

Certainly, the media played it as a long-overdue victory for Scopes. “Court Rules in a ‘Scopes Case’,” read the headline in one major national news magazine. Time led off with a reference to Inherit the Wind. Life mixed fact and fiction by reminding readers that the issue first “erupted in a glorious explosion in the tiny burg of Dayton, Tenn., where in 1925, as every student of American humor knows, Spencer Tracy gave Fredric March the verbal thrashing of his life.” A front-page article in the New York Times described the Epperson case as “the nation’s second ‘monkey trial’,” but declared that it “reached a strikingly different result” from the first one.21

Even the seemingly decisive Epperson decision, however, failed to resolve the fundamental issues raised by the Scopes trial. This occurred in part because Fortas simplified those issues along lines suggested in the Scopes legend. In its effort to portray McCarthy-era intolerance, Inherit the Wind implied that antievolution laws left only biblical creationism in the classroom. Fortas carried this interpretation into the Epperson decision when he stressed that “Arkansas did not seek to excise from the curriculum of its schools and universities all discussion of the origin of man” but solely teaching about evolution. Some antievolution leaders of the 1920s might have liked to have only creationism taught, but Bryan publicly argued for the state to bar teaching evolution on the express assumption that public school teachers already could not present the biblical view.22 By thus casting his argument as one for neutrality in education on the controversial topic of human origins, Bryan was able to gain support for antievolution laws from nonfundamentalists.

Defense counsel at Dayton did not endorse the idea of teaching both evolution and creationism in science courses. Darrow consistently debunked fundamentalist beliefs and never supported their inclusion in the curriculum. Hays and the ACLU argued for academic freedom to teach Darwinism but most likely did not consider the possibility that some teachers might want to cover creationism. Malone came the closest of anyone at Dayton to endorsing a two-view approach to teaching origins when in his great plea for tolerance he declared, “For God’s sake let the children have their minds kept open—close no doors to their knowledge.” Yet this came shortly after he had shouted at prosecutors, “Keep your Bible in the world of theology where it belongs and do not try to… put [it] into a course of science.”23 Addressing the relatively easy case of teaching only creationism as opposed to effectively ending classroom study of human origins, Fortas struck down the Arkansas antievolution law as “an attempt to blot out a particular theory from public education.”24

Fortas clearly intended to free public schools from restrictions against teaching evolution, but his written opinion backfired when certain fundamentalists misinterpreted it as an invitation to include creationist views in public education. “In Epperson v. Arkansas the Supreme Court overturned a law prohibiting instruction in evolution because its primary effect was unneutral,” a creationist legal strategist argued. “This unneutral primary effort [arose]… from an unneutral prohibition on only evolution without a similar proscription on Genesis.”25 Following such reasoning, some fundamentalists called for balancing instruction in evolution with creationist teaching as a supposedly constitutional alternative to excluding any one theory. Fortas may have thought that the earlier Supreme Court ruling barring religious instruction in public schools adequately covered this situation, but he did not anticipate the tenacity of fundamentalists who believed that scientific support existed for their creationist beliefs. Bills and resolutions mandating equal time or balanced treatment for creationism soon began appearing before state legislatures and local school boards throughout the nation. Proponents turned the Scopes legend to their benefit by widely quoting a fictitious statement attributed to Darrow at Dayton, “It is ‘bigotry for public schools to teach only one theory of origins.’”26

Of course, the force of this movement sprang from the vast number of Americans who hold creationist views, and not from any encouragement given it by either the Epperson opinion or the Scopes legend. “Debate over the origin of man is as alive today as it was at the time of the famous Scopes trial in 1925,” pollster George Gallup reported, on the basis of a 1982 public opinion survey, “with the public now about evenly divided between those who believe in the biblical account of creation and those who believe in either a strict interpretation of evolution or an evolutionary process involving God.” This and other polls consistently found over 80 percent support for including creationist theories in the curriculum.27

On the strength of such sentiments, three states adopted laws mandating creationist instruction in public schools before the Supreme Court stepped in to stem the tide. In 1974, Tennessee mandated “an equal amount of emphasis” in biology textbooks for alternative theories of origins, expressly including the Genesis account. Seven years later, Arkansas and Louisiana enacted laws requiring “balanced treatment” in biology instruction for “creation-science”: the Arkansas act linked this so-called science to the study of a biblically inspired list of creation events, such as a worldwide flood, while the Louisiana statute defined it as “scientific evidence for creation and inferences from those scientific evidences.”28 These three laws fell in separate lawsuits, and the media compared each of them to the Scopes case.

The Scopes legacy did more than merely influence media coverage of these cases; it shaped their very tone and timber. Drawn by the Scopes connection, the ACLU led the fight against all three statutes, with prominent New York counsel serving as their agents in the latter two cases. “It is a strange feeling,” the ACLU’s 97-year-old founding director Roger Baldwin commented upon passage of the Louisiana statute, “here’s where I came in [with Scopes], and here’s where the ACLU goes out to another battle to defend the same principles of freedom.”29 Challengers stressed the Scopes connection in all three lawsuits because it highlighted the religious purposes underlying the statutes and thereby provided a ready basis for striking them down. The first two statutes obviously violated establishment clause principles by expressly mandating public school instruction in biblical doctrines, and federal courts quickly disposed of them. The Louisiana statute simply called for teaching about scientific evidence for creation, however, and its defenders maintained that such teaching would not constitute religious instruction. Here, the Scopes legacy helped the challengers to prevail.

“The case comes to us against a historical background that cannot be denied or ignored,” a federal appeals-court panel noted in its analysis of the Louisiana statute. “The Act continues the battle William Jennings Bryan carried to his grave. The Act’s intended effect is to discredit evolution by counterbalancing its teaching at every turn with the teaching of creationism, a religious belief. The statute therefore is a law respecting a particular religious belief… and thus is unconstitutional.” A bare majority of the circuit’s fifteen judges affirmed this ruling on review, but seven dissented—and tried to turn the Scopes legacy inside out. “The Scopes court upheld William Jennings Bryan’s view that states could constitutionally forbid teaching the scientific evidence for the theory of evolution,” Judge Thomas Gibb Gee wrote for the dissenters. “By requiring that the whole truth be taught, Louisiana aligned itself with Darrow; striking down this requirement, the panel holding aligns us with Bryan.” Both sides thus claimed the moral high ground that was by then almost universally associated with the Scopes defense.30

The battle over the Scopes legacy continued when the Supreme Court agreed to review the Louisiana statute. “We need not be blinded in this case to the legislature’s preeminent religious purpose in enacting this statute,” Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., wrote for the majority. He then referred “to the Tennessee statute that was the focus of the celebrated Scopes trial in 1925” as an antecedent for the Louisiana law. Writing for the dissent, however, Justice Antonin Scalia offered quite a different view of the Scopes precedent. “The people of Louisiana,” he contended, “including those who are Christian fundamentalists, are quite entitled, as a secular matter, to have whatever scientific evidence there may be against evolution presented in their schools, just as Mr. Scopes was entitled to present whatever scientific evidence there was for it.”31 These clashing applications of the Scopes legend illustrate its broad appeal as folklore. Brennan could just as easily invoke it to support freedom from religious establishment as Scalia could use it to support academic freedom to teach alternative theories.

Some fundamentalists already have adopted the latter approach. When state or local education officials seek to follow the Supreme Court decisions on religious instruction in public schools by stifling conservative Christian teachers from presenting evidence for creationism in science classrooms (as happens with increasing frequency), antievolutionists often liken it to the alleged persecution of John Scopes. Courts readily dismiss the analogy by reasoning that Scopes wanted to teach a scientific theory while the others wanted to present their religious beliefs. This does not satisfy fundamentalists, however, who view their beliefs as truer than any scientific theory, because for them religion (and not science) is founded on personal experiences and relationships.

In a thoughtful discussion about such a case that arose in California during the early 1990s, the Yale law professor Stephen L. Carter concluded that the issue ultimately involves questions of epistemology. Who does have “the right,” he asked, to decide what gets taught as science in the public schools? Creationist parents and teachers, based on their relatively subjective religious beliefs, or professional scientists and educators, based on their relatively objective scientific theories? “The rhetorical case against the creationist parents rests not merely or mostly on arcane questions of constitutional interpretation,” Carter observes, “the case rests on the sense that they themselves are wrong to rely on their sacred texts to discover truths about the world.”32 Darrow fully realized this at Dayton, and used his defense of Scopes to challenge fundamentalist beliefs. To the extent that lawyers defending the evolutionist position in later lawsuits appeal narrowly to constitutional interpretation, fundamentalist beliefs remain unchallenged.

Certainly the court decisions since the Scopes case have not slowed the spread of creationism. Instead, they have encouraged fundamentalists to abandon evolution-teaching public education for creation-affirming church or home schooling. This relatively new development built on the earlier movement for separate fundamentalist colleges that went at least as far back as the fundamentalist–modernist controversy and gained momentum after the Scopes trial. Concern over teaching evolution contributed to both developments. In his foreword to a 1974 biology textbook written for fundamentalist high schools, for example, the creationist leader Henry M. Morris attributes “the widespread movement in recent years toward the establishment of new private Christian schools” to the perception among fundamentalist pastors and parents that “a nontheistic religion of secular evolutionary humanism has become, for all practical purposes, the official state religion promoted in the public schools.”33 His text offers a markedly different theology for the science classroom.

Not all conservative Christians reacted to the Scopes legacy with such defiance, however, especially after a self-proclaimed “new evangelical” strain of American Protestantism emerged following the Second World War under the inspiration of William Bell Riley’s hand-picked successor, the evangelist Billy Graham. In his public ministry, Graham ignored the Scopes trial and antievolutionism. In 1954, he endorsed The Christian View of Science and Scripture, a new book by the Baptist theologian Bernard Ramm that sought to reconcile conservative Christians to modern science by interpreting the Genesis account as a pictorial depiction of progressive creationism spanning eons. Ramm’s influential book, which cleared a path to the serious study of science for a generation of evangelical college students, dismissed “Bryan’s miseries at the Scopes trial,” as Ramm called them, as part of a “sordid history” that “we will not trace.”34 This approach fit Graham’s objective of resurrecting a biblically orthodox creed free from the cultural baggage that made fundamentalism unacceptable to most educated Americans. Mindful of the ridicule heaped on Bryan for his testimony at Dayton, scholars within the new evangelical movement typically view militant antievolutionism as deadweight to be cast off.

Many other American Christians feel even less direct impact from the Scopes legacy than evangelicals. Modernists and mainline Protestants typically share the common culture’s reaction to the trial and legend. Despite their traditionalism, American Catholics did not join Bryan’s antievolution crusade, in part because they already had their own parochial schools and colleges, which left them in the position of spectators to the Dayton trial and its aftermath. Rooted in a historic faith adaptable enough to accept theistic evolution, Roman Catholics sat out this culture clash. Yet the issue will never wholly disappear so long as fundamentalists continue to object to teaching evolution, which they persist in seeing as damnable indoctrination in a naturalistic worldview that undermines belief in God.

Certainly the Scopes legacy clings fast to Tennessee, where most people still profess the Christian faith and most Christians lean toward fundamentalism. Republicans targeted that traditionally Democratic state during the 1994 elections, with strong support from conservative Christian political forces. In an attempt to survive the onslaught, the state’s senior Democratic U.S. senator went so far as to prepare a television commercial touting his support for school prayer, but to no avail. Republicans swept into power throughout Tennessee, and new legislation to restrict teaching evolution in public schools soon appeared in the state senate with the support of fundamentalist groups and individuals. About the same time, the Alabama board of education ordered that new biology textbooks carry a disclaimer identifying evolution as “a controversial theory…, not fact,” and the Georgia house of representatives passed a measure facilitating instruction in creationism. “Yet it’s the Tennessee debate that has helped put the issue on the national stage,” USA Today reported. “It was in Tennessee in 1925 that the two sides squared off in Scopes’ epic trial.” The feature article discussed the 70-year-old trial at length, and included pictures of Darrow, Bryan, and Scopes.35

Largely due to the Scopes connection, the new legislation drew international attention. “Seventy years after John Scopes was convicted of teaching evolution in Dayton, Tenn., the State Legislature here is considering permitting school boards to dismiss teachers who present evolution as fact rather than a theory of human origin,” began a front-page article from Nashville in the Sunday New York Times.36 The British Broadcasting Corporation sent a camera crew to cover the story, complete with interviews in Dayton. Some American network news accounts featured clips from Inherit the Wind. Newspaper articles inevitably dwelt on the Scopes trial. Amid a flurry of hostile media coverage, the senate education committee approved the proposal by an eight-to-one vote, and sent it on to the full senate, which debated the two-sentence bill for three days. “Coming more than 70 years after Tennessee’s 1925 anti-evolution law was held up to international ridicule during the Scopes Monkey Trial, the bill again has brought national attention to Tennessee’s ongoing debate of how to teach the origins of life on Earth. Cameras and reporters jammed into the Senate for the debate,” the Memphis Commercial Appeal reported.37

Opponents dubbed the bill “Scopes II” and “Son of Scopes.” They devoted more effort to warning of its public-relations impact than to defending the theory of evolution. “This echo of the 1925 law that led to the Scopes monkey trial,” the Nashville Banner commented, “can’t help but make the state look bad.” The ACLU vowed to challenge the law in court, with its Nashville director warning, “I have already had several calls from teachers who are willing and interested in being plaintiffs, people who are interested in being the next John Scopes.” Finally, the senate’s presiding officer and senior member declared, “I can’t vote for this bill, but I don’t want anybody to think I don’t know God,” and the bill failed by a vote of twenty to thirteen. Observers credited the Scopes legacy for the defeat.38

The legislation evoked mixed reactions in Dayton. “I believe if they had the trial again today it would turn out about the same way,” Harry Shelton had commented a few years earlier, although he grudgingly conceded, “Now they permit the teaching of evolution in most schools—as long as you teach it as a theory and not as a fact.” Another former student called the new legislation “Silly, silly,” and Fred Robinson’s now elderly daughter added, “It’s a lot of hooey.” Teachers at the new regional high school keep quiet about the proposal at the request of their principal. The town’s population has tripled since 1925, spurred by a new furniture factory and better roads to Chattanooga. Memories of the trial draw tourists, too, with a Scopes Trial Museum in the old courthouse and an annual Scopes Festival featuring dramatic reenactments in the courtroom. The local newspaper editor likes the proposed new statutory limits on the teaching of evolution. “To my knowledge, it’s never been proven, even when we put on the trial here,” he noted. From the hill above town, Bryan College’s creationist biology professor agreed, adding that the bill “strikes a very profound chord in an awful lot of people.” In addition, these people—fundamentalists mostly—continue to read and hear arguments (much like those once made by Bryan) that challenge the scientific authority of Darwinism. With Bryan College faculty overseeing the town’s portrayal of the Scopes trial, the Commoner and his ideas still get a fair hearing in Dayton.39

The deeply entrenched Scopes legend continues to dominate impressions of the trial elsewhere. Even in Nashville, the morning newspaper dubbed debate on the 1996 legislation as “Inherit the Wind: The State Sequel.”40 One week after the bill’s defeat, Tony Randall’s production company revived Lawrence and Lee’s play on Broadway, with the character representing Bryan appearing fatter and more disreputable than before. Theater critics hailed the play as pertinent and timely. “We still have the creationists versus the evolutionists,” a reviewer on public television commented, and pointed to the new antievolution bill “in, yes, the state of Tennessee.” Whereas its review of the original Broadway production criticized the script’s “overall lack of tension” and “clinical quality,” the New York Times now praised the text’s “dramatic life.” The critic explained, “Here was a headline-making heavyweight bout between the rational thought of a newly rational age and old-fashioned Christian fundamentalism, which was deemed to be on its last legs, though today it’s alive and well and called Creationism.” The New Yorker, which originally scorned the play as “a much too elementary study in black and white,” now lauded it as “a thoughtful, powerful explication of religious and political issues that we still haven’t figured out.” A sign in the theater lobby quoted 1996 presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan’s comments in support of the Tennessee bill.41

These changing responses help account for the enduring public interest in both the play and the trial. To “intellectuals” of the 1950s, as Hofstadter noted, the Scopes trial seemed “as remote as the Homeric era,” and some of them criticized the play’s simplistic presentation of America’s debate over science and religion. Such critics typically accepted a scientific explanation for human origins and assumed that virtually all thinking Americans did so too, even those who believed in God. Certainly Inherit the Wind grossly simplified the trial, yet regardless of their position on the issue, many Americans perceive the relationship between science and religion in just such simple terms: either Darwin or the Bible was true. Hofstadter recognized this. “The play seemed on Broadway more like a quaint period piece than a stirring call for freedom of thought,” he observed. “But when the road company took the play to a small town in Montana, a member of the audience rose and shouted ‘Amen!’ at one of the speeches of the character representing Bryan.”42

As the amens for creationism have increased in both number and volume over the years since 1955, secular critics have tended to revise their views of the play and the trial. Even aloof intellectuals have come to realize that a vast number of Americans still believe in the Bible and accept it as authoritative on matters of science. Moreover, if people accept the biblical account of special creation over the scientific theory of organic evolution, which is, after all, one of the core theories of modern biology, then they most likely defer to biblical authority on other matters of public and private concern. For Americans who do not share this religious viewpoint and who fear that fundamentalists constitute the majority in some places, concerns about the defense of individual liberty under a government by the people seem all too familiar. The character representing Darrow in Inherit the Wind might just as well be standing in the doorway of their bedrooms as that of a small town’s schoolhouse—blocking the entrance of frenzied townspeople, and turning them aside by debunking their overzealous leader. The original Broadway cast did not take fundamentalist politicians seriously, Tony Randall observed shortly after the play’s revival in 1996, “but America has moved so far to the right, that they are now close to the center.”43

Although Lawrence and Lee’s dramatic plea for tolerance originally may have been targeted against the McCarthyites, with fundamentalists standing in as straw men, the straw men have proven to be more durable than the intended targets—and the threat to individual liberty that they symbolize has become increasingly ominous for some Americans as the power of government has grown over the ensuing years. Indeed, the issues raised by the Scopes trial and legend endure precisely because they embody the characteristically American struggle between individual liberty and majoritarian democracy, and cast it in the timeless debate over science and religion. For twentieth-century Americans, the Scopes trial has become both the yardstick by which the former battle is measured and the glass through which the latter debate is seen. In its 1996 review of Inherit the Wind, the New York Times described the original courtroom confrontation as “one of the most colorful and briefly riveting of the trials of the century that seemed to be especially abundant in the sensation-loving 1920’s.”44 Dozens of prosecutions have received such a designation over the years, but only the Scopes trial fully lives up to its billing by continuing to echo through the century.