LUNDENWIC—A VIKING TRAVEL MAP—BRITAIN’S VULNERABILITY—RAIDS INTENSIFY—THE FRANKISH EXPERIENCE—TRADE AND —PRODUCTION—MINSTERS AND THEIR ESTATES—VIKING SHIPS AND SEAFARING

Amerchant arriving at the trading port of Lundenwic around 830 would sail or row upstream on the flood tide, coasting past the crumbling stone walls of the ancient Roman city where St Paul’s church (Paulesbyri to contemporaries) and perhaps a royal residence stood—but not much else. The abutments of the Roman bridge might still have been visible, but the only crossing was by ferry. Just upstream of the mouth of the River Fleet the Thames takes a sharp southward bend towards what was once Thorney Island, for over a thousand years the site of Westminster Abbey and before that, perhaps, a Saxon minster. Between the two, along what is now the Strand, between Aldwych and Charing Cross, lay the busy wharves of Middle Saxon Lundenwic.

Founded by King Wulfhere of Mercia in the late 600s and described in 731 by Bede as ‘an emporium for many nations who come to it by land and sea’, it was not, perhaps, the great port it had once been.1 In those days, with a population in the low thousands,* it was substantially the largest settlement in the British Isles, one of only four contemporary settlements that we might recognize as something like a town with planned streets, close-set houses divided by narrow passages, warehouses, smithies, workshops, wells and all: noisy with the clang of smith’s hammers and the calls of longshoremen; reeking of tanners’ steeping vats and domestic waste. Its overall functioning was the responsibility of the king’s portgerefa, the port-reeve, whose erstwhile colleague had committed such a fatal faux pas on the coast of Dorset in the 780s. Through his reeve, the king charged tolls on arriving cargoes and administered the sometimes complex justice and trading rights of the many interested parties who made money there: regional noblemen, bishops, the abbots and abbesses of the great minsters; Frisian, Frankish, Danish and possibly Arab merchants, not to mention its indigenous or itinerant craftsmen and those farmers who supplied the settlement with meat and other provisions.

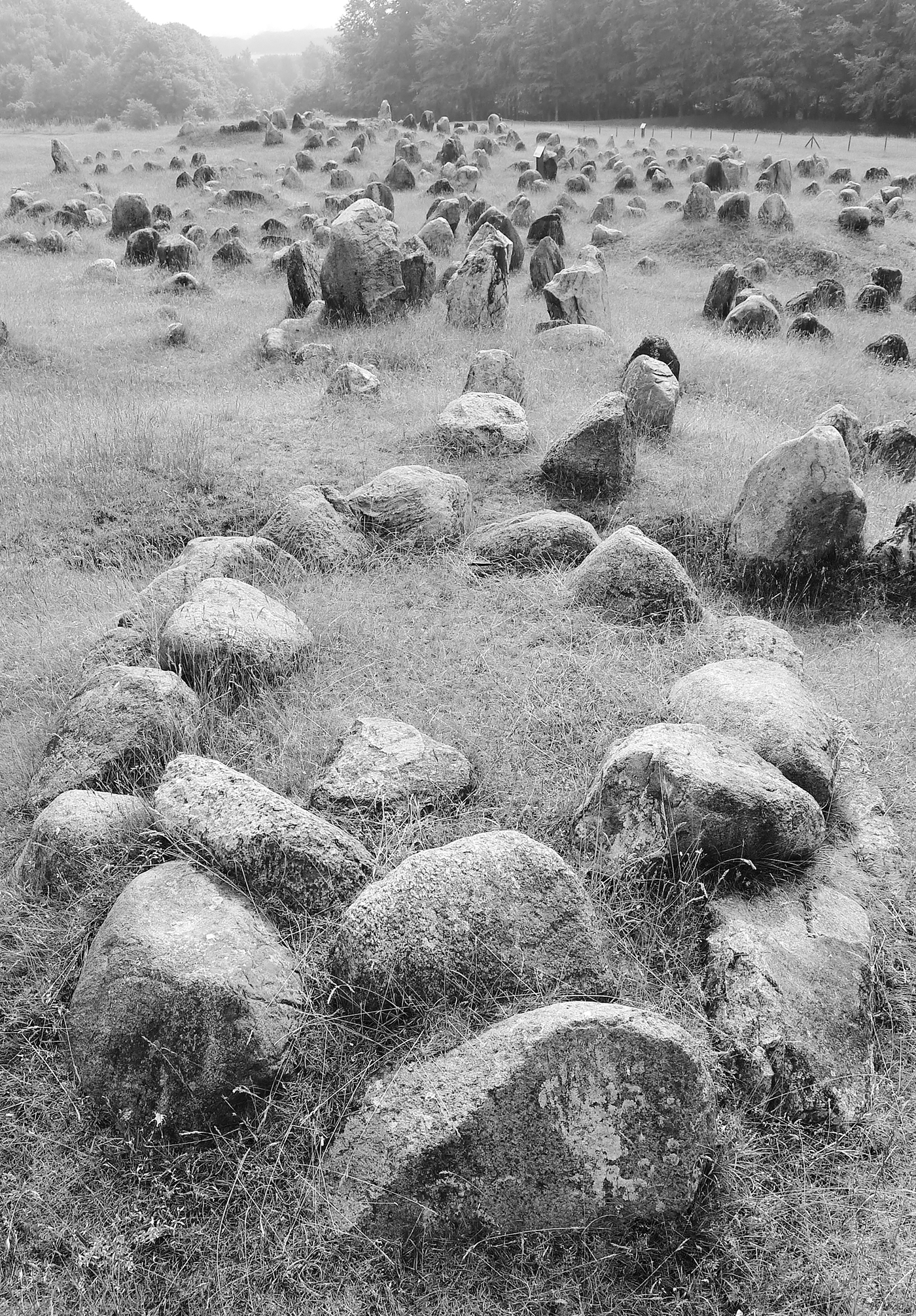

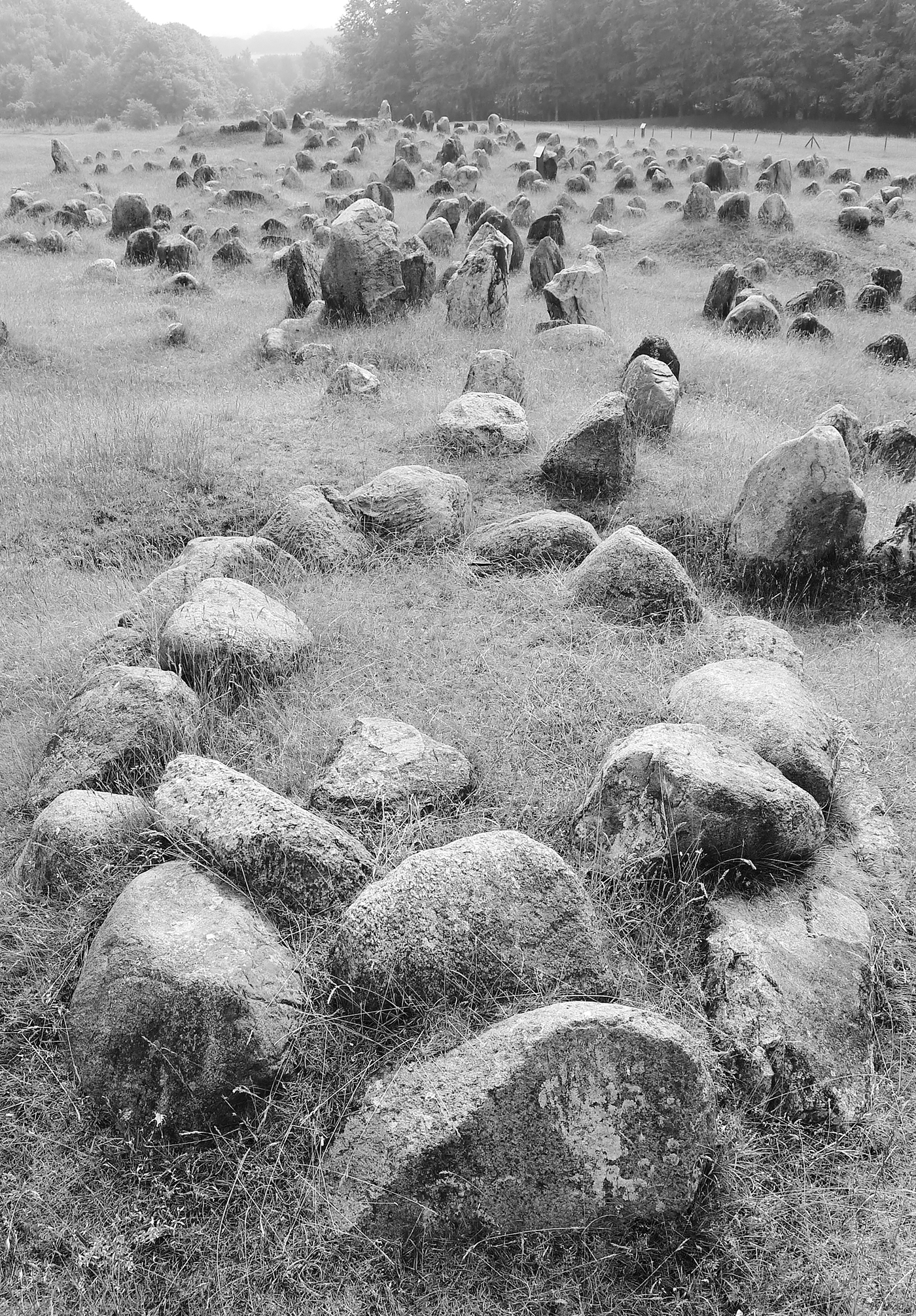

6. LINDHOLM HØJE: the memorial fleet of a seagoing culture, overlooking Denmark’s Limfjord.

In its eighth-century heyday Lundenwic, geographically part of the kingdom of the East Saxons, passed from Mercian to Kentish to West Saxon hands and back again: its value as a source of revenue and prestige and its prime location facing the Continental ports of Francia, Frisia and Denmark were constant sources of tension and opportunity. By the reign of King Offa (757–796) Lundenwic had already achieved its greatest wealth and extent.

The river frontage lay some 80–100 yards (73–90 m) inland from its present position; the Thames was a wider, slower river then and the Roman road running west from the city along the line of what is now Fleet Street and the Strand was set back from the river by less than 100 paces.† The main settlement lay to the north-west of this road, densest in the area of Covent Garden and with its north-west limit somewhere in the region of today’s fashionable Neal’s Yard. To the south-east of the road a natural terrace led down from the Strand to the foreshore, part of it revetted with piers and wharves where deep-draughted cargo vessels might tie up, and another part no more than a beach (the strand) where shallow-draughted boats might be pulled up above the tide and where temporary markets, very much a feature of these centuries, would have been held periodically.2 A church may have stood close to Lundenwic’s south-west edge on the site later occupied by St-Martin-in-the-Fields, on the corner of what is now Trafalgar Square. The port’s north-east corner seems to have coincided with the east side of King’s College and the Temple.

The shorefront deposits of Lundenwic lie buried some 16 feet (5 m) beneath the modern ground surface of the Victoria Embankment, a pleasant public park whence one might, these days, catch a pleasure boat, but whose commercial wharves are long gone. Across the river, on the Surrey side, a landscape of fen and water meadow was punctuated by natural gravel islands on which isolated settlements like the minster of Bermondsey benefited from access to the arterial Thames and its Roman road links to the north, east and west.

The recovery of Lundenwic’s past from brief passing mentions in contemporary sources,‡ but primarily from excavation, has been challenging and protracted. Until the 1980s scholars could not agree where Middle Saxon London stood. Archaeological investigations had concentrated on large commercial developments within the walls of the old Roman city from where, apart from the very evident presence of a church on the site of St Paul’s cathedral from its founding in 604, the seventh and eighth centuries were effectively missing. The contemporary interior of the city seems to have been largely uninhabitable marsh between natural prominences at Ludgate Hill and Cornhill along the River Walbrook.

In 1984 two archaeologists, Martin Biddle and Alan Vince, independently suggested that the Saxon town lay to the west, where place names like Aldwych (literally ‘Old wic’, a farm or trading site) were suggestive of a pre-Conquest presence and whence occasional fragments of Middle Saxon pottery had been retrieved over the years. Piecemeal interventions, sometimes nothing more than watching briefs undertaken as the bulldozers moved in, gradually assembled a case confirmed by the discovery in 1985 of sixth- and seventh-century burials and rubbish pits on the site of Jubilee Hall in Covent Garden.3 Now, these fragments combine to paint a lively picture of a thriving settlement, fleshing out the notices of travellers like the missionary priest Boniface in the early eighth century, Bede’s testimony, mentions in charters and coins minted here over the two centuries before Ælfred’s refounding of the city in the 880s.§

Lundenwic may have owed its origins to the convenient beach, its proximity to a minster church and its location near the old Roman city. But at some point in the late seventh century it was formally reorganized, its thoroughfares relaid on a grid pattern with house and warehouse plots of equal size sharing an axial orientation at right angles to the river. The same phenomenon can be seen in Godfrið’s foundation at Hedeby in Denmark, at Dorestad on the Rhine, at Hamwic close to Southampton and elsewhere, including Norse Dublin.

Like other trading ports Lundenwic lay undefended by palisade or garrison. Aside from a stream that bounded its south-west edge, Lundenwic lay grotesquely exposed, its weak domestic defences wholly inadequate against determined assault from the river. But its apparent decline after the end of the eighth century was not initially catastrophic, despite a series of fires from whose ashes it rose again. More likely, a range of economic factors was in play, not all of them obvious from the archaeological or historical record. West Saxon kings who managed to win control over Lundenwic may have promoted their own mercimonium,4 or trading port, at Hamwic at the mouth of the River Itchen on Southampton Water, to its detriment. Subtle shifts in trading networks, in production and profit margins, may have undermined its commercial power. Charlemagne’s short-lived economic blockade in the 790s cannot have helped.5 In Francia, a civil war between Louis the Pious and his sons from the late 820s seems to have disrupted the flow of royal patronage on which the great trading ports on the Continent relied for their continued success. The European silver supply was affected by events further afield, in the Abbasid caliphate. Other, even less tangible, elements can be dimly traced in the rise of rival centres of trade and production: the minsters.

A series of major seaborne raids that began in the 830s and lasted for twenty years and more sealed the fate of the great trading sites of north-west Europe. Dorestad, Quentovic, Lundenwic, Eoforwic (York), Hamwic and others never recovered from the attentions of those Scandinavian entrepreneurs for whom the ports became the destinations de choix to go a-Viking. Attacks on the Thames-side settlements in 842 and 851 finished Lundenwic, and the former Roman capital lay more or less deserted until the early 870s.6

*

Twenty-first-century citizen and visitor alike know London’s geography largely through the topological masterwork affectionately called the Tube map. People stare at it on giant posters long after they have found their destination. Thousands carry a miniature version in their pockets or bags. The Tube map is an abstraction of a vastly complex reality, in which travellers have only to orient themselves with the nearest access point that connects them to their destination: an underground railway station. No commuter much cares how deep the lines run, how they twist and turn to avoid natural streams, sewers and foundations, or how the system is maintained. Those stations, or nodes, are linked by linear routes of unvarying sequence: from Lundenwic’s heart, at Covent Garden, one takes a northbound train on the Piccadilly line one stop to Holborn, changes to the eastbound Central line and two stops later arrives at St Paul’s, in Londinium.

Like a Roman itinerary, on which places of interest were marked along theoretically straight roads, the Tube map invites its users to visualize, or at least recognize, a simple set of linear sequences, one for each colour-coded branch of the network. The stylized thick blue ribbon of the River Thames is the only concession to geographical reality. Thus, the District line, which runs 30 or so miles (48 km) from Richmond in the west to Upminster in the east, serves sixty such nodes, which schoolchildren and commuters alike learn by heart: Kew Gardens, Gunnersbury, Turnham Green, Stamford Brook, Ravenscourt Park, and so on, in unvarying succession from west to east. Trains may be late, or cancelled; but Baron’s Court will always come before Hammersmith. Where lines intersect, commuters transfer from one branch to another: from District line to Piccadilly, Victoria or Northern line, and so forth. Branches run far out from the centre into what purports to be bucolic countryside. The map serves a population of more than 10 million people and an area of more than 600 square miles or 384,000 acres. By contrast, Lundenwic covered 150 acres, less than half a square mile.

In attempting to make sense of the geography of the Viking Age, to envision how Scandinavian raiders and traders mastered a world of coast and open sea, of river and hinterland, it is worth imagining that world as a network like the Tube map (see p. 50). Consider, to begin with, Britain’s complex, island- and estuary-ridden coast as a long, thin conceptual rectangular route whose inshore waters constitute something like a maritime Circle line: on the ground it traces a path very unlike a circle, but like its underground counterpart the coast acts as a continuous loop on which bored passengers might fall asleep and still conveniently arrive at their intended destination—eventually. Imagine that theoretical rectangle, the outline of British inshore waters, as a line on which vessels encounter a sequence of possible destinations and intersections: harbours, churches, river estuaries; royal fortresses. Imagine, also, the route of the River Thames (a theoretical dead-straight line running right to left, east to west) intersecting with that line at a point between Shoeburyness and Sheppey. This is a maritime/riverine interchange.

Following the Thames due west, the Early Medieval sailor would pass, like a litany of commuting stations, settlements on Sheppey itself, on Canvey Island, at Tilbury and Barking, before reaching Lundenwic. Travellers with business at settlements upriver (a royal residence at Kingston; minsters at Chertsey, Dorchester and beyond) need only follow its course until, after perhaps a week’s passage, they reached Cricklade, deep inside what is now Gloucestershire on the edge of the Cotswolds. Here, not much more than 20 miles (32 km) from the Severn estuary, they might disembark and continue to the centre of the salt trade at Droitwich along the existing Roman road network, or to Gloucester in the ancient kingdom of Hwicce. The Severn links Gloucester with the Bristol Channel, the River Wye as far north as Hereford (Here-pæth ford: army-road crossing), and the Irish Sea; further upriver, at Tewkesbury, the Warwickshire Avon penetrates the Mercian heartlands.7 In the Viking Age, north from the Thames estuary, the mouth of the River Orwell gave access to the substantial and long-lived trading centre of the East Angles at Gipeswic (Ipswich), a highly significant source of trade with the Continent, with London and the interior of eastern England through its craft industries and port infrastructure.

From the Wash, which in the ninth century was more extensive than it is today, the River Great Ouse offered a direct line of inland communication, via various tributaries and linked waterways, to Stamford, to Thetford in the kingdom of the East Angles, to great minsters at Ely and Peterborough (Medehamstede) and inland as far as Bedford, Cambridge and perhaps also Northampton on the River Nene.

Further north, where the great Circle line of the British coast intersects with the broad Humber estuary, vessels could sail inland along the Yorkshire Ouse as far as the former Roman colonia at Eoforwic (York) where the third of Britain’s international trading ports lay in the kingdom of Northumbria. Alternatively, a sharp left turn a few miles west of the Roman ferry crossing at Brough on Humber would bring a ship south along the Trent, past a trading and production settlement at Flixborough, as far as Lincoln (via the old Roman canal known as Fossdyke), Nottingham, Derby and almost to Lichfield—itself joined to the salt-producing centre at Droitwich through the Roman road network. That network linked almost all the navigable heads of the major rivers: one giant communication and trading system. Roman administrators had conceived it as such, but also as a highway for their armies. Half a millennium later, it was to be co-opted by another race of entrepreneurial invaders.

Britain’s’ navigable rivers belong largely to the south, but on the west coast the Dee was navigable inland from the Irish Sea to a point beyond Chester; the Mersey as far upstream as Warrington; the Clyde perhaps as far inland as Lanark. In the east, the River Tees gave access at least as far inland as Worsall weir near Yarm; the Wear was accessible by boat as far as Chester le Street. The River Tyne gave access to monasteries at Jarrow, Monkchester, Gateshead and as far west at least as Newburn—a possible major royal residence close to Hadrian’s Wall and the trans-Pennine Stanegate road between Corbridge and Carlisle. Corbridge was a significant crossroads, linking the east–west road and river route with the great north–south Dere Street, connecting Dun Edin (Edinburgh) and Eoforwic.#

In Scotland, the Tay could be navigated at least as far up stream as the royal palace at Scone, heartland of the kingdom of Atholl, while the opposed inlets of the Forth and Clyde allowed deep penetration from the North Sea and Irish Sea. The Great Glen connected east and west further north. At other points along this circular route, monasteries, royal fortresses and sheltered harbours were the pearls in a necklace of seats of learning, of spiritual (and material) enrichment: repositories of the relics of powerful saints, centres of power and craft, safe havens, markets for goods and news or, depending on one’s point of view, deposits of easy cash.

Britain, thanks to its rivers, long-distance native tracks like the Icknield Way, and its Roman legacy of hard, direct, metalled roads maintained by trade and the kings’ armies, was extraordinarily penetrable. The ease with which goods and people were able to move across its fertile landscapes between settlements, rivers and production centres rendered it accessible to any pirate captain capable of remembering simple sequences of directions. It is no coincidence that important churches, royal residences, sites of councils and synods, battlefields, production sites and records of destructive Viking raids are all concentrated on these lines of communication: they are the key to Britain’s success, and to envisioning the impact of the Viking Age on the kingdoms of Britain. Over the course of half a century of raiding and reconnaissance Scandinavian seafarers equipped themselves with a detailed mental atlas of the British Isles, a conceptual Tube map that allowed them to access, at speed, almost every significant place in Early Medieval Britain.

7. PREHISTORIC LEGACY of a connected landscape: the ancient Berkshire Ridgeway.

*

The maritime raiders from the North showed themselves equally adept at political intelligence, exploiting opportunities presented by civil war, dynastic weakness and the preoccupations of neighbouring states. The conflict that broke out between Louis the Pious and his sons in the 830s, and which must have severely compromised the Frankish state’s coastal defences, provoked a rapid response from Norse opportunists. In 834 raiders laid waste the extensive trading settlement at Dorestad, sited on an old course of the River Rhine south-east of Utrecht in Frisia. A year later the first large-scale raid on an Anglo-Saxon kingdom was recorded, at Sheppey in the mouth of the Thames estuary. In 836 King Ecgberht of Wessex fought twenty-five pirate ships off Carhampton on the north coast of Somerset and was defeated, while the monks of the monastery of Noirmoutier at the mouth of the Loire, first attacked in 799, abandoned their island, taking the relics of St Philibert to safety at Tournus in Burgundy. A year later, in 837, the Annals of St Bertin noted a great Viking raid on the trading settlement of Domburg on Walcheren Island at the mouth of the River Scheldt. The picture, if incomplete, is clear: in the political vacuum created by Frankish civil war, Viking pirates roamed at will along the southern part of the North Sea and the English Channel. No contemporary force was able to defend the approaches to the coastal trading settlements.

In 839 King Ecgberht, ageing and tired after thirty-seven years on the throne of Wessex and having produced a viable, grown-up son to succeed him, wrote to Louis the Pious, tenuously restored to power and concentrating on bolstering his coastal defences. Might he, Ecgberht, pass through Louis’s kingdom on pilgrimage to Rome—in what was, effectively, an abdication?∫ In the same letter Ecgberht related a vision that had achieved widespread notoriety in England. It had been revealed to a priest that, in a certain church, boys (to be interpreted as the souls of grieving saints) could be seen writing down in blood all the sins that the English had committed. The priest was warned that if God’s sinners did not repent their sins and attend to the Christian feast days:

A great and crushing disaster will swiftly come upon them: for three days and nights a very dense fog will spread over their land, and then all of a sudden pagan men will lay waste with fire and sword most of the people and land of the Christians along with all they possess.8

As if to confirm God’s wrath a terrible flood killed more than 2,000 people across Frisia; Ecgberht was also dead within the year, having failed to achieve his ambition of reaching Rome but having rescued the ailing fortunes of his kingdom. In the same year Fortriu, the kingdom of the Northern Picts, suffered a devastating Viking raid in which its ruling dynasty was wiped out. Louis the Pious died, too, a year later, his empire split and factionalized.9 Overwhelming disaster must indeed have seemed imminent.

The raids continued, becoming more intense. Ireland’s suffering at the hands of Norwegian pirates, almost continuous for the first two decades of the ninth century, was exacerbated by Norse raiders establishing long-term bases, the longphuirt, at convenient coastal locations. By 841 the principal of these had been built on the south bank of the River Liffey at a place called Baile Átha Cliath, the ‘place at the ford of the hurdles’ close to the black pool, Dubh Lind, which gives Ireland’s capital its modern English name. Dublin’s Viking past has been sensationally revealed by a series of excavations that show a sophisticated, well-organized trading town developing over the course of the ninth century.10 Other longphuirt were established at Wexford, Waterford, Limerick and Cork: Ireland’s celebrated medieval towns owe their origins to piracy.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates that in 842 there was slaughter at three trading settlements: Lundenwic, Hamwic and Norðunnwig (probably Norwich). It was as if an immense raiding orgy had been planned and executed in the sure knowledge that Atlantic Europe, suffering an acute vacuum of effective military power, was theirs for the taking. Ecgberht’s successor as West Saxon king, his son Æðelwulf, fought against a large Scandinavian fleet off Carhampton and, like his father before him, was defeated. For the next five years the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is blank.

Viking attentions returned, during these years, to Francia. The three sons of Louis the Pious disputed the succession in a series of campaigns that lasted from 840 to 843. A bloody battle was fought at Fontenoy on the River Yonne, an eastern tributary of the Seine, in 841. Raiders took the opportunity to burn the port at Rouen. The following year Nantes and Quentovic were attacked; raiders overwintered on the monastic island of Noirmoutier at the mouth of the Loire. Embassies passed to and fro between the rival Frankish dynasts. In 843 peace was signed at Verdun, giving West Francia to Charles Calvus ‘the Bald’, East Francia to Louis ‘the German’ and Middle Francia, including the Rhineland, Frisia and Lombardy, to Lothair.

It is hard to tell how much institutional damage was sustained by the Frankish states in these years: the best evidence comes from the behaviour of the raiders themselves. In 845 the first substantial raid on the Île de la Cité in Paris on the Seine, deep inside northern Francia’s heartland, showed how dangerously exposed the soft underbelly of Charlemagne’s former empire had become. Paris was no mere riverside trading village; it had been a Roman city, Lutetia, with a grand basilica, St Etienne, two splendid bridges and an iconic island location: the former capital of Clovis, first king of a united Francia, from 508. Its port controlled trade along the Seine and its tributary the Marne. If Viking raiders, wasting and pillaging as they sailed and rowed upstream, could penetrate so far into Frankish territory, the arteries of the empire lay open.

The razing of the trading ports was a commercial nuisance; the attacks on monasteries had been local, highly personal, psychological disasters whose effects on the greater institutions of the church were, initially, low key. Buildings were trashed; lives lost; labour taken into slavery; material wealth stolen. But landed property and rights had not yet been appropriated by the executive arm of the heathen Northern menace; refugees were not on the move in large numbers, so far as we can tell. The attack on Paris showed, for the first time, that Scandinavian raiders might threaten to tear the essential fabric of the Christian state.

Charlemagne’s, now Lothair’s, capital lay to the north, at Aachen (in French, Aix-la-Chapelle), between the Rivers Meuse and Rhine. During the year in which Paris was attacked his new kingdom was assaulted by a huge fleet, said to comprise 600 ships, sent from Denmark by King Horik along the Elbe. Lothair managed to defeat them and, in the following year, was able to sign a peace agreement with Horik. The interests of Charles the Bald, focused primarily on Aquitaine and the South, were divided by necessity: a war with Brittany, asserting its independence; rebellions on the Spanish border and a bold Viking raid along the Garonne as far inland as Toulouse.11 Paris lay at the edge of his radar. His pragmatic response was to pay the raiders off with a treasure of 7,000 livres of silver,Ω the first of thirteen such ‘Danegelds’ extracted from Frankish kings.

Historians debate the merits of ransoms paid to raiders, of the dangers of setting such precedents, with the benefit of hindsight. But Charles was inventing a Viking policy on the hoof; the kings of Atlantic Europe would watch and learn from his mistakes and successes over the next three decades and, often, adopt similar expedient solutions. Those same raiders, sailing down the Seine with their ships full of bullion, had sufficient space and nerve to fill their boots on their way home, laying waste the coastal communities of the Channel; they might well have asked themselves how often they could repeat such profitable exercises.

*

The Frankish and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms survived Viking assaults on their trading ports because the essential wealth of north-west Europe lay in its agricultural and industrial surplus and internal trade, not in its economic relations with the rest of the Continent. Merchants had succeeded in evolving emporia from beach markets, often located on the boundaries between kingdoms, and had done very nicely out of them. Kings, too, had seen the potential for raising cash at such sites, through tolls on imports and by recycling and minting silver, hiving off a percentage. Sometimes they allowed powerful clergymen and women to trade free of tolls and to mint their own coinage in such places. The richer minsters, and bishops, possessed their own warehouses at some of these sites. Nevertheless, the economies of Atlantic Europe succeeded because they produced sufficient cattle and grain to support kings, armies and minsters, and such regionally distinct and specialized surpluses as salt, lead, cloth, pottery, furs, antler, glass and iron to largely satisfy domestic consumption.

Since the end of the Roman imperial state, which had operated under a command economy, emergent kingdoms had succeeded by a combination of cash-raising through warfare and the imposition of customary renders: goods and services owed by units of land to lords higher up the chain of rank, from ceorls to thegns to ealdormen to kings. Those renders were collected at vills and on royal estates, where they were consumed by peripatetic lords and kings on an unending cycle through whose mechanisms they also dispensed justice and distributed wealth and favours, ensuring a smooth bilateral flow of patronage and reciprocal obligation.

The alienation of estate lands from the king’s portfolio to the church, a gradual process beginning in the first half of the seventh century, affected this system significantly, and increasingly. Minsters, those churches established and maintained by communities of monks, nuns and their unfree tenants, were static institutions whose legacy was a form of sustained capital. They were able to invest in agriculture and manufacture because the fruits of their labours were inherited directly by the community, in an unmoving location with fixed estate boundaries. When we hear about St Cuthbert acquiring land and negotiating with kings long after his death, we have to envision the saint operating from beyond the grave as the symbolic embodiment of those who survived him and continued to function as his community.

Abbots and abbesses were both physical and spiritual manifestations of the community’s heritage and privileges. Kings, their right to rule legitimized by the church, liked to believe themselves the inheritors of the same functions with regard to the state; but still they were obliged to travel through their lands consuming food, managing the services of their warrior élites: putting it about. The only personal wealth that they could retain was portable treasure in the form of bullion. The estates, with their arable and meadow lands, rivers, quarries and woodlands, were the kingdom’s infrastructure. Public projects, so far as we can tell, were confined to the construction of dykes and bridges and occasional repairs to Roman roads.

Increasingly, from the late seventh century, minster communities were able to invest in the construction and maintenance of mills, forges and workshops for the crafting of vellum, antler, horn, metalwork, grain and cloth. They began to enclose fields and specialize production.≈ The larger establishments gradually became centres for the gathering of surplus raw materials and the conversion of that surplus into products that might be traded—for books; for craftsmen expert in masonry, sculpture and glazing; for wines, dyes and oils imported from the Continent. Their surpluses included grain, increasingly of the valuable bread wheat varieties; wool and woollen cloth; timber; ironwork; ale; books where the skills existed to create them; honey; wax for candles; and livestock bred specially for markets such as the trading ports. At what point some of the greater minsters began to look like trading settlements, even towns, is a moot question.

The evolution of minsters as central places is also, and perhaps even more significantly, traced in their secularization. Originally founded either under royal patronage or by ascetics and charismatic holy persons, minsters were aristocratic institutions, often ruled by collateral members of royal kindreds and increasingly divorced from the spiritual fervour which had led to their foundation between about 635 and 700. By the second quarter of the eighth century Bede was already complaining that royal estates were being given over, with their highly valuable freehold, to persons unsuited to the strict rule of monastic life. He was, in effect, accusing lay aristocrats of taking monastic vows simply in order to avoid the burdens of military service and food render, and so as to be able to bequeath land to their heirs.12

By the beginning of the ninth century, as the cases of Cwenðryð and others show, minster estates might be acquired as a means of expanding the property portfolios of the landed élite, sometimes in a calculated effort to acquire key resources such as salt, lead, iron and timber. Monastic lands and privileges began to change hands for cash on an open market in which bishops and archbishops were active. The tensions that grew up between those minsters whose communities were substantially composed of monks and nuns in holy orders, and those controlled largely by secular canons, were played out very publicly during and beyond the Viking Age. They form a parallel, equally compelling and significant narrative to the more obvious headline acts of raiding and settling.

The sorts of transactions by which such monastic estates changed hands can be traced through the increasing use of charters to ‘book’ those lands and by subsequent attempts to alter, forge and invent such titles or the privileges and lands that went with them. Charter donations were often recorded during ceremonies at great assemblies; sometimes, if not always, the transfer was tangibly confirmed by the placement of the enacting parchment and a sod of earth from the land in question on to the altar of the recipient church.13 The Historia de Sancto Cuthberto is highly instructive in this context. It was likely compiled in the tenth century by the community of the venerable Northumbrian holy man, bishop and abbot of Lindisfarne, whose disinterment as an uncorrupted corpse in 698, eleven years after his death, assured his celebrity as the greatest saint of northern England. The Historia purports to record the history of that community, especially in those years after it fled Lindisfarne in the face of Viking attacks; its relations with kings; and the means by which it lost or came into possession of its estates.14

The original gift of land, by King Oswald in 635, consisted of two royal estates, Islandshire and Norhamshire, close to what is now the Scottish border with Northumberland; others followed under Oswald’s successors.15 Over the next two centuries further estates were acquired, and we are afforded a unique glimpse of the mechanisms by which the early minster portfolios were accumulated. During St Cuthbert’s lifetime Lindisfarne received a royal grant of lands at Crayke, near York, so that the holy man might have somewhere to stay when travelling to that city, and at Carlisle, in the formerly independent British kingdom of Rheged—both, it seems, as part of a deal in which Cuthbert would leave contemplative retirement on Inner Farne to take on the politically critical and onerous bishopric of Northumbria at a time of key church reforms.

The same king, Ecgfrith, later gave the community lands at Cartmel and Gilling, after Cuthbert raised a boy from the dead.∂ In 679 Cuthbert was granted an estate at Carham on the banks of the River Tweed because his prayers for the king’s victory against Mercia in a battle on the River Trent had been successful. King Ceolwulf of Northumbria, the dedicatee of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, abdicated in 737 and, retiring to Lindisfarne, brought with him the gift of a substantial royal estate at Warkworth on the Northumbrian coast;16 and so it went on. Later kings, notably Osberht,π ‘stole’ some of these estates and recycled them to the royal portfolio although, almost needless to say, he was divinely punished for the offence.∆ Behind these donations lie political realities: a king’s need for ecclesiastical and divine support; the hope of sins expiated and of assured entry into the everlasting joys of heaven; the need to liquidate assets in a time of crisis.

No Early Medieval minster site can be reconstructed in its entirety: almost all of them lie beneath later churches and towns and we are only ever afforded glimpses of their layout and workings. Our model minster is a compilation of hard-won fragments: a church, perhaps two churches; monks’ cells, a guest house; an enclosing vallum or ditched enclosure. Mills, a key marker of stability and technical innovation, have been excavated at Tamworth, Wareham, Barking and Ebbsfleet in England (all associated with minster complexes) and, most extensively, close by the island monastery of Nendrum at the head of Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland.17 Many others, such as that identified by the excavators of Portmahomack, must have stood among the several hundred minsters in existence in the eighth and ninth centuries. At the same Pictish site vellum was produced at an industrial complex which required expertise to construct, manage and maintain it. The smiths’ hall at Portmahomack also shows how much infrastructure was required for the iron-working industry; and a seventh-century charter survives which records the gift of an iron mine in the Kentish Weald to the abbey of St Augustine in Canterbury.18 Rights to deposits of lead ore and to stone quarries which fed monastic sculpture workshops were similarly granted to and traded by ecclesiastical communities. The larger establishments, such as the twin monasteries of Jarrow and Wearmouth in Northumbria, boasted nearly 600 fratres, or brothers (effectively their supply of cheap manual labour) in the early eighth century.19 Their minster complexes, with lofty stone buildings, stained glass windows and the craftsmen to maintain them, were the most sophisticated institutions of their day.

If the smaller minsters, whose existence can often only be inferred, relied mostly on their food renders for survival, the greater establishments were able, with their large labour forces and extensive estates, to operate as sustained economic enterprises. Some minsters seem to have evolved relationships with outlying farms that either supplied their provisions while the minster intensified production of particular livestock, grain or manufactured goods, or supplied specialist materials to them. Archaeologist Duncan Wright calls them ‘home farms’.20 Often these seem to have been situated upstream from minsters on rivers so that their produce might be floated conveniently downstream. Lands were not acquired randomly, but to supply key resources or to fill niches in a minster’s portfolio, like woodland for coppice or marsh for reeds and waterfowl.

The minster of St Peter at Medehamstede, later known as Peterborough, is unusually well documented. Although its surviving founding charter is a later forgery, analysis shows that its core lands were formed out of a small defunct Anglian fenland kingdom, North Gyrwe, in the seventh century.21 These lands were rich in riverine resources, enjoying access through inland rivers to the Wash and to unknown numbers of island communities, amounting to around 600 hides—that is, the render expected from the estate was worth that of 600 family farms. The minster of St Peter was no minor foundation. Its original estate was donated by King Wulfhere of Mercia from about 674, later enhanced by generous lands across the East Midlands, whose inclusion in its portfolio must have reflected the need for the minster to be supported by more than just the grazing, fishing and fowling of the fens.

An entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 852 records the leasing by the abbot of Medehamstede of an estate at Sempringham, some 30 miles (48 km) away in Lincolnshire, providing that the estate still rendered annually to the minster sixty waggon-loads of wood, twelve of brushwood, six of faggots and sundry other items. Sempringham, it seems, rendered to the minster its requirement for timber and firewood—nearly 80 tons of it a year. Such were the functionings of the monastic economy. Minsters at Brixworth in Northamptonshire, Yarnton in Oxfordshire and Ely in the Cambridgeshire fens were focal points for densely clustering settlements, interacting with them economically and, we might suggest, socially.22 King Wulfhere’s apparent role in the foundation of both Medehamstede and the trading port of Lundenwic is suggestive of increased royal interest in trade and exchange; and that interest seems also to have driven a dramatic increase in the administration and quantity of coinage at the same period.

If this sounds as though a small industrial revolution were taking place in parts of Britain, the historian and archaeologist must exercise caution: this is not a full-blown medieval manorial system but a series of local and regional responses to opportunity. Even so, minsters produced and traded goods because they had become centres of consumption, not as a coherent strategy to stimulate the economies of their kingdoms. Their unique advantages, in privileges and international connections to a Europe-wide web of Latinate, educated, capital-intensive centres of social and economic excellence, loaded trade in their favour, and they exploited it to the full.

However, although there is a broad consensus that minsters evolved during the eighth century as central places with a range of social, economic and spiritual functions (including burial) the picture has to be pieced together from disparate sources. Such evidence as exists shows a dramatic rise in trade after about 725. The phenomenon is easiest to detect in East Anglia, where the first post-Roman industrial manufacture of wheel-finished, kiln-fired pottery at the trading port and production site of Gipeswic (Ipswich) seems to have been stimulated by an influx of Flemish potters from the Continent in the 720s. Fragments of Ipswich ware turn up in excavations across the region, with small quantities reaching as far south as London and Kent, inland along the Thames corridor, through Lincolnshire and as far north as York.23 A single sherd has been recovered from excavations at Hamwic on the south coast.

The distinguished ceramicist Paul Blinkhorn believes that the pottery, often retrieved from sites with ecclesiastical associations, reflects a rapid expansion of internal trading networks across the kingdom of East Anglia, just as finds from the trading ports of the east and south coasts echo international production and exchange in high-value luxury goods.24 Evidence from excavated rural settlements, both secular and ecclesiastical, seems to show that this expansion in trade coincided roughly with physical structural alterations: re-alignments of buildings; construction of rectangular enclosures—suggestive of intensive, specialized farming. In East Anglia the new type of pottery, showing a limited range of forms, is found almost exclusive of any other local wares: it became a badge, almost, of regional identity.

*

Widespread gifting of royal estates to the church over 200 years across the kingdoms of Britain and Ireland fostered dynamic, productive economies which those of Scandinavia could not match. In Norway, Denmark and Sweden opportunities for the forms of patronage and exploitation evolving in partnership with the church and a compliant, not to say enthusiastic, warrior élite, were extremely limited: fertile land was scarce and confined to narrow coastal plains. Shifting alliances and groupings of warrior kindreds, often armed to the teeth and with vengeance in their hearts, were not easy even for the most formidable kings to control.

The agricultural, industrial and political expertise of the Insular peoples, in part indigenous and in part learned from the Romanized Frankish empire, was largely absent from the loose-held kingdoms of Scandinavia. They did not enjoy the legacy of an Imperial road system or the protection of its ruined forts. Their seafaring, mercantile and boat-building skills were, however, highly advanced. With those skills Scandinavian raiders were able both to relieve the western Christian kingdoms of some of their material wealth and to observe at close quarters the sophistication of their economies. They admired much of what they saw. The price which Bede had foreseen the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms paying, in their enthusiastic patronage of the church, was that, economic miracles and statehood notwithstanding, they surrendered something of the military prowess with which they had amalgamated the small kingdoms of the post-Roman tribal reshuffle.

The Insular psyche saw its world in terms of produce, labour, patronage, lordship and regional bragging rights, tied to the soil. The poor, unlanded, unfree cottar travelled to the ceorl’ s farmstead with his or her waggon-load of wood, eggs or wool; the ceorl to his lord’s vill to render his services to a thegn; thegn travelled to ealdorman or to abbot and might occasionally fight with the men of his shire against their neighbours. Ealdormen travelled through the lands of their shires dispensing justice in disputes over boundaries, livestock, theft, murder and the return of escaped slaves. They led their levies into battle against their, or the king’s, enemies and, like the bishops, attended royal assemblies. Kings concerned themselves with exacting tribute and toll; with planning and plotting their succession; with their wills and with treasure chests full of scrap metal and precious objects; with the activities and ambitions of rivals at home and abroad; with the distribution of gifts and favours; with the movements and provisioning of their warriors and the probity or otherwise of their moneyers.

It is hard to exaggerate the psychological unpreparedness of the Insular states against a fast-moving, water-based, entrepreneurial enemy with nothing to lose but their skins, playing by a new set of rules and uncaring of retribution, their wives and children safe at home waiting for son, brother, husband to return home from what amounted to a hunting expedition, with bounty to supplement their meagre living from fishing, farming and domestic crafts.

Scandinavia was uniquely blessed with a tradition of excellence in shipbuilding, with ample supplies of slow-grown, straight-grained wood, supreme skills in carpentry and a seaward-facing culture. Long experience, experimentation and competition for naval supremacy led, by the middle of the ninth century, to something like perfection in the construction of a wide variety of vessels capable of deep-sea sailing, coastal trading, raiding, and the penetration of navigable rivers. Ships were more than merely transportation: in Scandinavian culture they carried a symbolic role greater even than that of Britain’s eighteenth-century ‘wooden walls’: they were named, famed, celebrated in song and verse as sea steeds riding the whale road.

On the north bank of Limfjord in northern Jutland, close to an important ancient crossing point, lies the Viking period cemetery of Lindholm Høje.** Hundreds of graves, the cremated remains of villagers and traders, are marked by placements of stones in the unmistakeable shapes of boats. The gently sloping hillside looks like nothing so much as a grassy harbour crowded with jostling stone ships, a flotilla of memorials tying Danish culture to the sea and to boats. Ship burials are known from Orkney, the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, mainland Scotland and England, most famously the monumental burial of King Rædwald at Sutton Hoo overlooking the River Deben in Suffolk—the legacy of Scandinavian contact before and during the Viking Age. In Scandinavia they occur, as at Sutton Hoo, in association with royal cult sites. At Lindholm Høje a more subtle rendering of maritime sensibility is displayed; no ships were buried here, but the cemetery’s inhabitants saw themselves as peoples of the sea, cremated on pyres, like Beowulf, before being, as it were, launched on to the breeze-ruffled waters of the afterlife.

The famous Norwegian ship burial at Oseberg,†† excavated in 1904, was no abstraction of salty sentiment; no mere model. The length of a cricket pitch, 22 yards (20 m), the Oseberg vessel, clinker-built of oak planks, had been buried in a huge trench and, to ensure that it stayed put, it had been ‘moored’ to a large boulder. This was the last resting place of two royal women, interred with their waggons, sleighs, weaving equipment, horses, dogs and treasure, as well as provisions and equipment for their last journey. Constructed in about 820, the Oseberg ship lies three quarters of the way along the evolutionary path towards the perfect Viking vessel, represented by another Norwegian burial: the Gokstad ship. Their clean, refined lines, their high carved prows, shallow draught and rakish low freeboard, are predatory refinement: these were fast, light war machines with no concession to comfort, designed for attack and a quick getaway. The Oseberg ship had served her time on inshore waters for more than a decade before being sacrificed to the otherworldly needs of her queenly owners.

For a deeper understanding of Scandinavian shipbuilding craft and the brilliance of its technologies, one must travel to Roskilde at the head of a long, narrow fjord on Sjælland, the largest island of the Danish archipelago.‡‡ Here you can see longships and their more modest cargo-carrying cousins being built and sailed, and talk to the craftsmen and sailors who study, construct and crew them. At some time in the eleventh century Roskilde Fjord was blocked, 15 miles (24 km) north of the city, at a place called Skuldelev, by five ships deliberately scuttled to prevent attack from the sea—Scandinavian states were as vulnerable to Viking predation as the rest of north-west Europe.

8. CARSTEN HVID, skipper of the Sea Stallion of Glendalough, in the rope works at Roskilde ship museum, Denmark.

In 1962 the five vessels were excavated from inside a temporary coffer dam and their remains form the core displays of the Roskilde Ship Museum. An admirable programme of research has led, first, to the reconstruction of these vessels in order to understand their capabilities, technologies and materials and, second, to the development of expertise in the shipbuilding techniques of the Viking Age. The Skuldelev ships offer a hint of the wide range of vessel designs belonging to the regional repertoire, from the small inshore two-bench rowing boats called færings, to medium range cargo vessels (the knarrs ), to larger deep-sea trading ships; from small warships of the snekkja type right up to the cruisers of their day, represented by Skuldelev 2, a longship 100 feet (30 m) long and 12 feet (3.8 m) wide, designed for a crew of sixty, with a mast and square sailing rig.

In 2007 Skuldelev 2, reconstructed as the Sea Stallion of Glendalough, was sailed and rowed to and from Dublin, at an impressive maximum speed of 15 knots. The voyage commemorated Viking links with Ireland, especially poignant because Skuldelev 2 had been built on the banks of the Liffey in the middle of the eleventh century.

Scandinavian ships had many design features in common: all were clinker-built with overlapping strakes; all were equipped with oars, many also with a single mast that bore a square, woollen sail for use when the wind lay aft. Unlike Mediterranean and Frankish vessels, they were plank- rather than frame-built. The earliest ships were built up from a keel plank rather than a true keel, to which the first strakes, or hull planks, were attached on either side. Each successive plank was fastened in order to fashion the basic shape of the hull; internal framing, a keelson§§ and mast step were added to stiffen the hull later. Strakes were generally attached using clench nails (effectively large iron rivets), their joints caulked with moss, tar and wool.

9. THE SEA STALLION OF GLENDALOUGH, a reconstruction of Skuldelev 2, which sailed from Roskilde Fjord to Dublin in 2007.

Aside from the larger cargo vessels, broad in the beam and relatively deep-draughted, ships were designed to sail in shallow water, often as little as 2 feet (60 cm) deep, and so that they could be pulled up on to a sloping beach or drawn overland on skids. The lack of a true keel until, for example, the Oseberg and Gokstad ships of the ninth century, meant that at sea ships made substantial leeway: they slid sideways and downwind of their intended course. The exaggerated leeway meant, in turn, that with their square-rigged sails they could not make rapid progress to windward except by rowing. Steering was accomplished with a side-rudder so that the clean, sweeping leaf-shaped lines of the vessel, and her stiffness, should not be compromised by a stern transom.##

The experimental ships built at Roskilde and elsewhere have demonstrated without doubt their virtues of speed, manoeuvrability and seaworthiness. Their design allowed them to flex like fish in heavy seas, and the subtly perfect form of the stem, or prow, ensured that high waves were swept beneath the hull: these ships planed over waves rather than plunging into them. That the tools used in their construction were so simple (for the most part axes, adzes, chisels and augers) and that the techniques used in their construction were so refined, is the unwritten testimony of more than a thousand years of seagoing tradition, of a culture umbilically joined to the waters of the Baltic and the north-east Atlantic.

Much scholarship has been devoted to the question of Viking navigation. First-hand knowledge of inshore waters developed by generations of sailors, traders, fishermen and raiders contributed to the construction of a mental marine chart, the Viking Age ‘Tube map’ described earlier in this chapter. Out of sight of land, greater skill was required to navigate safely. Compasses were unknown in Northern waters in the Viking Age, but knowledge of the positions of the sun, moon and stars, the behaviour of waves and cloud formations, of marine animals and birds, and ‘dead-reckoning’ (calculating one’s position by estimating speed and direction over a long period) must all have been employed. The jury is, as yet, out on the possibility that Scandinavian deep-water skippers made use of crystals such as Icelandic spar, whose properties include polarizing light, to find the direction of the sun beneath cloud.∫∫

The geography of north-west Europe offered its own characteristic advantages for navigators: sailing west from Norway the north–south alignment of Shetland’s islands and the position of Orkney close to the Scottish mainland meant that landfall was difficult to miss. Those navigating the Outer Hebrides enjoyed similar fortune: one island led south-west towards the next. Britain’s intricate, complex coastlines, with their distinctive headlands, bays and estuaries, were an unfolding chart to the experienced sailor. Local currents, tides and landmarks must all have become part of the conscious repertoire of the seafaring skipper and, as Scandinavian captains and their crews explored increasingly distant waters, their confidence grew.

It is also a convenient truth that in springtime North Sea currents allow relatively easy passage west despite the prevailing westerlies of these latitudes; and in autumn, both currents and winds provide a reliable passage back to home waters. By the dawn of the ninth century no part of the British coastline was unexplored by Scandinavian seafarers. Orkney and Shetland may even, by 800, have undergone a first phase of Norse settlement.

A much later source, the thirteenth-century Orkneyinga Saga or History of the Earls of Orkney, gives us an idealized picture of the dedicated Viking life, one dominated by agriculture but infused with the wandering spirit of the seafarer, as convincing a portrait as any written of the archetypal eighteenth-century frigate captain by a long-suffering grass widow. Of Svein Asleifarson we hear that:

Winter he would spend at home on Gairsay, where he entertained some eighty men at his own expense. His drinking hall was so big, there was nothing in Orkney to compare with it. In the spring he had more than enough to occupy him, with a great deal of seed to sow which he saw to carefully himself. Then, when that job was done, he would go off plundering in the Hebrides and in Ireland on what he called his ‘spring trip’, then back home just after midsummer, where he stayed until the cornfields had been reaped and the grain was safely in. After that he would go off raiding again, and never came back till the first month of winter was ended. This he used to call his ‘autumn trip’.25

The Roskilde collection allows us to picture the range of ships owned and deployed by these farmer-pirates. We might envision Svein Asleifarson’s vessel as a small longship like Skuldelev 5, 18 yards (16 m) long with twenty-six oars, a crew of thirty men and a maximum speed of 15 knots. Its draught, at just 2 feet (60 cm), allowed it to penetrate the shallowest waters and navigable rivers. But it is possible that he used something more modest; the sort of fishing boat represented by Skuldelev 6, carrying a crew of just fifteen or so. We must, I think, allow for a wide variety of regional and functional types, of traditional style and personal preference; and, indeed, as the Skuldelev vessels show, for conversion, upgrade and modification.

British and Irish seagoing communities had their distinctive vessels too: there may have been dozens of local and regional forms, from the simple woven lath coracle to a modest skiff rather like the two-bench færing, to the seven-bench assault vessel inferred from the Dál Riatan Senchus fer nAlban.26 The Irish currach, in its many forms, survives as a uniquely adapted boat-building tradition, and a variety of other types is suggested by references in contemporary sources such as Adomnán’s Vita Colombae.

Only one Insular Viking Age vessel has been recovered by excavation, to tell of an otherwise entirely lost shipbuilding tradition. The Graveney boat, recovered from a muddy channel in Kent in 1970, was a small trading vessel, not unlike a færing in size. When sunk, by accident or design, she was carrying hops and Rhineland quern stones, and must have been typical of boats engaged in small-scale cross-Channel trade in the ninth century. No warship from Irish, Scottish, Welsh or Anglo-Saxon fleets has yet been found intact.

King Ælfred seems to have been the first to establish something like a strategic fleet for naval defence, although the Franks evidently had substantial numbers of vessels under royal control. For the Insular kingdoms, facing inwards to their rich arable lands and pastures, ships were for trading and fishing, or for small-scale transportation of warriors. With the exception, perhaps, of Dál Riata, they had no overseas ambitions. Their ships were no match for a determined marine assault. Nevertheless, in a naval engagement recorded by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under the year 850, Ealdorman Ealhhere and the Kentish regent Æðelstan, eldest son of Æðelwulf, king of Wessex, fought against a Viking fleet at Sandwich in Kent and were able to capture nine ships. That speaks of competence, built up over the previous two generations, to deal with small- and medium-sized fleets.

If the summer raiding season and the homebound wind were such reliable aids to those skippers who took their men a-Viking, the Atlantic kingdoms must have enjoyed some respite during the months of darkness, storm and ice. At least, that is, until the winter of the year 850 when, for the first time, a Scandinavian fleet, perhaps the remnants of that defeated off Sandwich, made its decision to overwinter on the Isle of Thanet: the prelude to 100 years of invasion, conquest, response and integration.

* Cowie and Blackmore (2012) estimate some 6,000 inhabitants. I must say I am sceptical of a figure this high; but population of any Early Medieval settlement is notoriously difficult to estimate.

† The Strand was probably at that time called Akemennestraeteliterally, the road to Bath, the Roman Spa town of Aquae Sulis, later Aquamannia (Watts 2004). The road runs in a giant curve north-west from London towards Bicester before turning south-west.

‡ A very useful list of those sources mentioning not just Lundenwic, but also the other major trading settlements of Atlantic Europe, can be found in Hill and Cowie 2001.

§ Boniface was a West Country son of a wealthy family, educated at a monastery near Winchester. He left England in 716 to join Willibrord, the so-called apostle of the Frisians. He was famous for having felled an oak tree sacred to the indigenous pagans. He became archbishop of the newly founded German church and was killed by bandits in 764 on a last mission in Frisia (Talbot 1954).

# See p. 322.

∫ Ecgberht had been exiled in Francia in his youth by Offa and by his predecessor Beorhtric (ASC 839). He may well have known Louis personally.

Ω A rough equivalent, perhaps, to the wergild or head-price of a hundred ealdormen.

≈ Hence such commonplace Middle Saxon place names as Goswick (goose farm); Keswick (cheese farm); Berwick (barley farm), and so on.

∂ Cartmel, on the South Cumbrian coast; Gilling in Yorkshire.

π Died 867; possibly reigning from 849.

∆ See below, pp. 101–2; he was killed in battle against the heathens.

** A splendid museum nearby tells the story of the settlement, its graves and excavations. Danish archaeology has a long and distinguished tradition of excellence in excavation, publication and display.

†† Oseberg lies 30 miles (48 km) or so due south of Oslo in Vestfold, Norway. The Gokstad vessel comes from a site just 10 miles (16 km) further south.

‡‡ Denmark consists of the northern two thirds of the Jutland peninsula and more than 400 islands. At its closest point the largest island, Sjaelland, is less than 2 miles (3 km) across the Oresund from the coast of Sweden at Helsingborg.

§§ A keelson was a member running from stem to stern to attach internal framing to the keel below.

## Transom: a transverse, flat stern, as if the natural leaf shape curve towards a point has been cut off.

∫∫ Sunlight is refracted by the rare crystal in such a way that, in northern latitudes, weak polarization of sunlight can be detected by an observer looking through it in the direction of the sun even on a cloudy day.