AMBITION AND REALITY—NORTHUMBRIA—GOOD FENCES—THE STATUS QUO—GOVAN—FAMILY WEDDINGS—DEATH OF EADWEARD—DIPLOMACY AND PATRONAGE—ÆÐELSTAN, OVERLORD

In the Northern politics of the Viking period nothing is quite so simple as it seems. Land surely changed hands by fair means and foul; but the bald account of theft and insult, of good lords and perfidious heathens in the piously partisan Historia de Sancto Cuthberto masks a more subtle navigation through these difficult waters.

The lands which the community of St Cuthbert had given to the faithful Elfred before his flight from Corbridge comprised three large estates in a contiguous strip along the north Durham coast, between the rivers Wear and Tees.* North of these lay territories that the community had acquired (or reacquired) by dint of its support for King Guðroðr in the 880s, during which time it settled on generous estates in and around Chester le Street, the old Roman fort straddling the Great North Road on the banks of the Wear. Another set of lands which came into the possession of the community of St Cuthbert during that period consisted of a large triangular tract in the north-west of what is now County Durham, circumscribed by the rivers Derwent and Wear and Roman Dere Street.1

41. THE STORY OF THE FISHERS OF MEN—or Thor’s fishing expedition: a cross fragment from St Andrew’s church, Andreas, Isle of Man.

In the aftermath of his famous victory at Corbridge in 918, Rögnvaldr gave Elfred’s coastal estates to two of his senior jarls, Scula and Onlafbald (the latter supposedly struck down by Cuthbert’s wrath in the church at Chester le Street). The Historia records that in this same time one Eadred, son of Ricsige, ‘rode westwards across the mountains and slew Prince Eardwulf, seized his wife’ and then fled to the protection of St Cuthbert at Chester le Street.2 Like Elfred, Eadred was given lands by the community—the very triangular parcel, in fact, that lay in the north-west of the county. Like Elfred, he held his lands faithfully until the arrival of Rögnvaldr, who slew him at the Battle of Corbridge in 918. This huge estate was now given by the Norse conqueror not to one of his own followers, as one might expect, but to Eadred’s sons.

How to unpick this? To start with the realpolitik of the Early Medieval North, we can say that there was historical antipathy between the kings of southern Northumbria—that is, ancient Deira—and the lords of Bamburgh, formerly the seat of the kings of Bernicia. St Cuthbert had been a protégé of the Bernician dynasty of Oswald (now a posthumous cult figure in Mercia); but since the infamous raid on Lindisfarne in 793 the weakness of Bernician royal authority had driven Cuthbert’s community west and south on an epic seven-year tour around their lands, until they settled on their estate at Chester le Street. These territories were the ancient marcher lands between Deira and Bernicia; and it seems that by cleverly sponsoring the half-Scandinavian Guðroðr in the early 880s the community had taken up a buffer position between the two rival kingdoms. A buffer, certainly, but very much as the ally of the Men of York. It was Guðroðr who donated the estates between Tyne and Wear to Cuthbert’s community. The saint had abandoned his former patrons in Bernicia; or they had abandoned him.

His community (in the guise of its bishop) generously allowed two successive exiles, Elfred and Eadred, to enjoy the fruits of these lands in return, we suppose, for military service: for protection. But for protection against whom? First, it seems, against the revived lordship of Bamburgh, whose alliance in 918 with Constantín in Scotland must have seemed threatening to them. Second, against the new and even more unappealing threat (unappealing because the grandsons of Ívarr were, and always would be, unrepentant heathens) represented by Rögnvaldr. Elfred’s background is obscure, although it is quite possible that he was a brother of Eadred. The latter, we are told, was the son of Ricsige—a rare name. A Ricsige was king in York in the 870s, in the days of Rögnvald’s infamous grandfather and of Hálfdan and, therefore, a Deiran client (or puppet) of the Great Host.†

Now, perhaps, we can put the pieces together. Suppose that the ‘prince’ Eardwulf slain by Eadred somewhere in the west was a member of the Bernician royal household, a brother of Ældred son of Eadwulf.‡ It would follow that the community at Chester le Street had employed these senior Deiran warriors as military proxies against their enemies in the north and west, in return for the renders of several large estates. They rewarded Eadred with the lands that protected their north-west flank, and Elfred with the vulnerable coastal strip. But their protectors were driven off or killed during the invasion by Rögnvaldr which the combined armies of Alba and Bernicia could not halt on the battlefield. The community of St Cuthbert now lay dramatically exposed and vulnerable, its lands a prey to faithless incomers and historic rivals.

*

THE ESTATES of the community of St Cuthbert in the ninth and tenth centuries

Rögnvaldr assumed the reins of power at York where there had been, as we suspect from its submission to Æðelflæd earlier that year, an interregnum—a vacuum in military and regal authority. In doing so he might, without too much perfidy, have regained control of lands which his predecessor Guðroðr had ‘given’, or leased, to St Cuthbert. One bloc of that land he divided and gave to two of his jarls as a reward for their part in his victory; the other he allowed to be kept by Esbrid and Ælstan, the sons of the slain Eadred who were, as members of the Deiran royal house, entitled to such magnanimity as the price of their loyalty to the new power in the land. And Rögnvald’s interests in protecting his marcher lands against threats from the north were shared by the community at Chester le Street. Their interests were, at least partially, aligned.

Eventually, as the wheels of dynastic fortune turned during the later tenth century, and as the Historia laconically puts it, St Cuthbert, ‘regained his land’.§ The psychological power of the long-dead saint, and the political power of the militarily vulnerable community at Chester le Street, allowed them to maintain their lands and status through thick and thin, aligning their interests with those who would support them, or leave them alone. They played for high stakes and, by and large, were successful. Sometimes they got through by the skin of their teeth.

*

In the search for evidence of such expressions of tension and accommodation, the excavated remains of urban and rural settlement are of limited help. The cultures of north-west Europe built houses much like each other. They raised cattle and sheep in the same ways; they ate pretty much the same diet. Their choices in dress and accessories, as much matters of personal concern then as now, were dictated by fashion, price and availability so that in early tenth-century York, for example, native and Scandinavian alike seem to have made, traded, bought and worn a mix of local, regional and foreign ornaments, trims and fabrics. Cultural imperialism seems not to have been expressed in the domination of foreign tastes over native. The patterns of people’s lives were dictated, for the most part, by local custom and by their distant lords, their humdrum lives played out well below the radar of kingly warfare, treaty and submission.

Richard Hall, the excavator of Coppergate, in reviewing the mass of evidence for Viking Age York or Jorvík, concluded that instead of aligning themselves overtly either with native Northumbrian cultural values, or with those of incoming Scandinavian warlords, its citizens may have consciously adopted both, occupying a cultural centre ground: what Dawn Hadley, the Viking Age scholar, has paraphrased as ‘innate affinities with ambiguity’.3 It is a striking thought: an exercise in delicate cultural fence-sitting, constantly negotiating identity in ways familiar to expatriate communities everywhere. How conscious people were of the significance of their behaviour is another matter.#

42. NORSE RUNES ON A CROSS SHAFT from Kirk Braddan Old Church, Isle of Man.

Only occasionally are we afforded glimpses of the mechanisms by which royal authorities tried to balance such cultural tensions. The Ordinance concerning the Dunsæte survives as copies in two medieval law texts, but most scholars place it in a tenth-century milieu.4 Written in Old English and from a West Saxon perspective, it nevertheless details matters of mutual interest to English and Welsh populations dwelling on either side of a river. The Dunsæte are identified with an area called Archenfield in English and Ercyng in Welsh, which flanked the River Wye between Monmouth and Hereford and which is now part of Herefordshire. The nine brief clauses of the ordinance are a reminder that the paramount interests of the Insular population were vested in livestock:

Ðæt is gif man trode bedrifð forstolenes yrfes of stæde on oðer...

That is: if anyone follow the track of stolen cattle from one river bank to the other, then he must hand over the tracking to the men of that land, or show by some mark that the track is rightfully pursued.5

Other clauses deal with the resolution of disputes, distraint,∫ the nature of oaths and so on. Such are the means by which cross-border relations are managed, ensuring that good fences (or rivers) make good neighbours, diffusing cultural tensions that seem so easy to inflame. More significant, perhaps, is the fact that in the Dunsæte Ordinance Welsh and English were treated equally: six men from each side were to sit in judgement on disputes; penalties for crimes committed by either side were the same, and English and Welsh livestock had the same values: 30 shillings for a horse (equal to that of a man) or 20 for a mare; 12 shillings for wild cattle; 30 pence for a sow; a shilling for a sheep; 8 pence for a pig; and twopence for the lowly goat. Here, largely isolated from the grand narrative of invasion and counterattack being played out hundreds of miles away, local issues were met with local solutions.

More than thirty years previously Ælfred and Guðrum had negotiated a similar set of ordinances, albeit on a larger territorial scale, to manage rights and obligations between their two jurisdictions where West Saxon and Mercian came into contact with the new Anglo-Danish entity in East Anglia. That treaty concerned itself with the legitimate movement of people from one side to the other; with trade relations and the pursuit of fugitives, the bona fides of traders and the warranties required for purchasing horses, oxen and slaves.

Eadweard’s policies, in the confused second decade of his reign when he was, so to speak, fighting fires along a broad front and had little time for formal law-giving, were part expedient and part local accommodation. His so-called Exeter law code, dating to between 906 and 917,Ω refers once to ‘the whole nation’ then to ‘the eastern and northern kingdoms’ in contrast to ‘our own kingdom’.6

In 916, after a successful campaign against Bedford, Eadweard persuaded the defeated Jarl Ðurcytel to depart with his men for Francia, under his protection and ‘with his assistance’.7 However long the Danish warlord had been in the English Midlands, it had not been long enough for him to call it home and, equally, the locals may have been glad to see the back of him; maybe they helped raise the fare. Bedford was its own borderland; its tensions perhaps more overt and problematic than those further north in Northumbria and the Five Boroughs. Early tenth-century statehood was a molten fluid being forged with old tools, but from unfamiliar materials.

Elsewhere, the king’s new peace in the conquered towns of Danish Mercia was more considered and subtle, as Rögnvald’s disposition of his new conquests in the north had been. Eadweard was able to reward his own followers with lands forfeited from jarls like Ðurcytel and in some cases he seems to have allowed Scandinavian lords to retain estates that they had acquired.8 In either case, as the final clause in the Dunsæte Ordinance makes clear, submission to the king, whether by Scandinavian jarls or indigenes, involved handing over tribute and hostages as sureties. Eadweard came to East Mercia not as liberator, but as expansionist overlord.

A corollary to large numbers of hostages and subject jarls arriving at the West Saxon and Mercian courts was that young nobles of Scandinavian or half-Scandinavian blood came to learn the ways of a new milieu; to mix with others of their own status and with the native élite. One imagines lively cultural interaction in both directions. On their ultimate return to whichever Midland territory they belonged, they must bring something of West Saxon or Mercian culture, laws and education with them, not to mention brides; and the same processes probably happened in reverse.

*

After the large-scale submissions at the end of a tumultuous year in 918, Eadweard sustained the hectic pace of offensive action and construction, apparently undaunted by the death of his sister and ally. The following year he secured the submission of Nottingham, which he occupied and garrisoned, diplomatically, with both Englishmen and Danes, according to the Chronicle. This was the cue for all the people of Mercia, of both races, to submit and accept him as their overlord.

Turning his attention now to the northern frontier, he had a fortress built at Thelwall on the River Mersey, the westernmost point of the boundary between Mercia and Rögnvald’s Northumbria.≈ A few miles upstream, on the north side of the river, he ordered that the ancient Roman fort at Manchester (Mamucium) be rebuilt and garrisoned.

In 920 Eadweard again went to Nottingham, that key site on the River Trent controlling trade and military access between Mercia’s heart and the North Sea. Now his levies constructed a fortress on the south side of the river, opposite the existing defences, and built a bridge to connect the two sides in the fashion employed by his father on the River Lea and following the precedent set so long ago in Francia.∂ In the same year the king advanced further north and constructed a new burh at Bakewell in the land of the Pecsætan, the dwellers among the Peaks. Then, the Chronicle records:

The king of the Scots and the whole Scottish nation accepted him as ‘father and lord’; so also did Rægnald and the sons of Eadwulf and all the inhabitants of Northumbria, both English and Danish, Norwegians and others, together with the king of the Strathclyde Welsh and all his subjects.9

This passage has stirred the blood of many a patriot historian over the centuries. Some have seen it as the founding charter of an English subjection of North Britain. Most modern commentators treat it with caution: first, because it is the propagandist account of the West Saxon court; and second, because submission to a temporarily superior overlord was an expedient fact of Early Medieval kingship. It is even possible that no such submission occurred at all outside Eadweard’s imagination. More likely, I think, he was able to agree with counterparts beyond the Humber that the status quo of 920 should be maintained, that hostages be exchanged and oaths sworn by all parties to uphold the peace within current territorial bounds. That is to say, Eadweard wished that the northern kingdoms should recognize his recent gains in the Midlands. He was in a strong position to make such a demand; they had little to lose by agreeing.

What, then, was the status quo in 920? In Alba, Constantín had proved himself able and willing to engage in great events beyond the southern edge of his kingdom. If we do not know the detail of his now twenty-year-long reign, we can say that his ambition and capabilities reflect dynastic stability, economic affluence and military competence, even if he had not been victorious at Corbridge. He could, in modern terms, mix it with Dublin Norse and with the kingdom of York; he established and maintained diplomatic relations with the southern English, as well as with the Bernician lords of Bamburgh. Some of his political capital was spent on endowing and patronizing the reformist Irish Céli Dé monastic movement:π he would be buried in their great foundation at St Andrews.

Something is also known of the geography of Scottish royal power in this period. The old core of northern Pictavia in Fortriu, around the Moray Firth, must now have been vulnerable to Norse predation and the threat of invasion. If Scone, in the old territory of Atholl, was a ceremonial and symbolic centre of royal and ecclesiastical power, and St Andrews a royal monastic foundation, then the focus of Constantín’s kingdom must now be placed in Strathtay and Strathearn. A royal palace and chapel stood at Forteviot, in a fertile alluvial landscape graced with grand high crosses (at Dupplin, for example) and craggy fortresses dominating the northern edge of the Ochils, the Gask ridge and Sidlaw hills and looking always towards the broad River Tay. Dunkeld, whose monastery had housed the relics of St Colm Cille, lay higher up Strathtay. Along with apparent political reform came a cultural Gaelicization which displaced the Pictish language, a process shrouded in deep and frustrating obscurity.

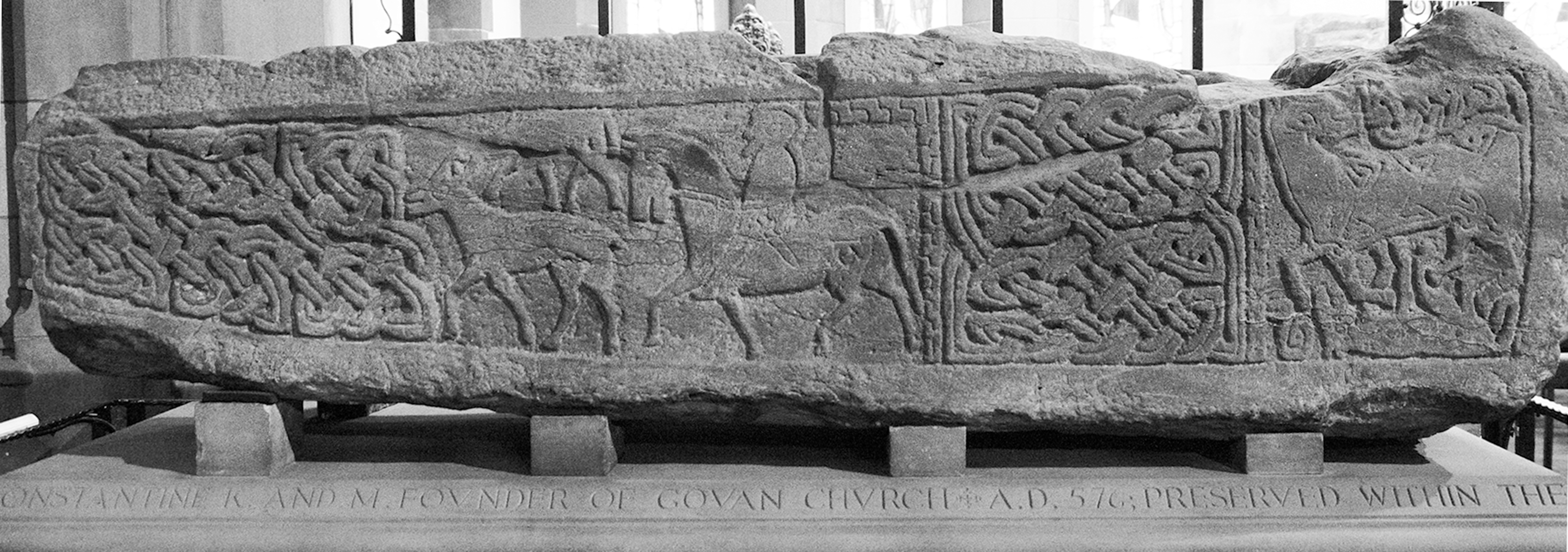

Constantín’s political control did not extend to the Western or Northern Isles; nor, probably, to Caithness, Sutherland and Ross. His rule seems also to have coincided with the revival of the ancient British kingdom whose kings had once been based at Alclud, Dumbarton rock. Strathclyde, or Cumbria, survived the destruction of its great fortress in a Norse attack of 870; its kings re-emerged as leaders of a cultural and military revival. If Constantín had invested his political capital along the upper reaches of the Tay basin, the kings of Strathclyde seem to have chosen a site further up the Clyde from Dumbarton on the south side of the river, at Govan. The Old Church here (an uncompromising late Victorian pile overlooking the post-industrial remnants of its once-great shipbuilding yards) contains a collection of Early Medieval sculpture whose only rival, in numbers and quality, is on Iona. The graveyard is huge and roughly circular, perhaps indicating an early foundation. In the Middle Ages this was the site of an important ferry crossing.

Thanks to recent investment the crosses, grave slabs, hogback tomb covers and a remarkable sarcophagus are beautifully displayed, with careful lighting that reveals the subtlety and creative achievement of an energetic, confident royal church. Like York, Govan displays ambiguities of identity: the hogback tombs are a distinct hybrid of native and Norse, pagan and Christian, embracing the tensions between a warrior caste and its pious responsibilities to the church, the playing out of old rules of patronage on a new psychological canvas. A possible Thing-mound called Doomster Hill once stood nearby, before its sacrifice to Glasgow’s nineteenth-century expansion.

43. THE MAGNIFICENT SARCOPHAGUS at Govan Old Church near Glasgow: a royal hunting scene.

The impressive lidless sandstone sarcophagus now housed inside the church, retrieved from the graveyard in 1855 and restored to a place of honour close to the altar, seems to have once housed the body or relics of a king.10 Its relief-carved decorative interlace encloses panels portraying a mounted warrior hunting deer with hounds; an unidentifiable animal trampling another underfoot; a serpent and various four-footed beasts. The dedication of the church is to St Constantine, perhaps reflecting the community’s original, or acquired, affiliation with a cult of the Roman emperor;11 but the style of the carving belongs to the ninth or tenth centuries, expressive of a revival of Strathclyde’s fortunes and of their historical pretensions. By the time that the British kingdom comes once more on to the radar of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the ‘submission’ of 920 its king, Owain, seems to have extended his overlordship as far south as Galloway and possibly into the lands that later became English Cumbria.

*

The kings of the Welsh, the Norðweallcyn (that is, by contrast to West Wealas, or Cornwall) had submitted to Eadweard at Tamworth in 918, not as conqueror but as the regal power inheriting an imperium exerted over them by Æðelflæd. That, at least, is the implication of the account in the Chronicle. But Thomas Charles-Edwards, the distinguished historian of Early Medieval Wales, offers another possibility. After an apparent Norse attack on Anglesey in 918 and a raid on Davenport, deep inside Cheshire, by Sigtryggr, the brother of Rögnvaldr, in 920, Eadweard moved decisively to reinforce north-west Mercia. In 921 he had a fortress constructed at Cledamuþa, which most scholars accept must mean Rhuddlan at the mouth of the River Clwyd.

In the same year the Annales Cambriae record a battle at Dinas Newydd—the ‘New Fortress’, which Charles-Edwards suggests may also be identified with Cledamuþa. In that context, of an unprecedented West Saxon move into Venedotian territory, rebellion by Idwal, the king of Gwynedd, followed by defeat and the joint submission of the grandsons of Rhodri Mawr is plausible. It is equally possible, as Charles-Edwards allows, that the battle was fought against forces from Dublin, Man and/or York, or against those Norse who had settled around Chester and the Ribble Valley; that Idwal and his cousins allied themselves with Eadweard against a common enemy, having sought his protection.

Rhodri Mawr, like Ælfred, Cináed mac Ailpín and Ívarr, is seen retrospectively as the progenitor of a great dynasty. His oldest son, Anarawd, inherited Gwynedd, with its principal royal llys at Aberffraw in south-west Anglesey. On his death in 916 Anarawd was succeeded in Gwynedd by his son Idwal Foel. Rhodri’s son Merfyn inherited the rule of Powys and was succeeded by his son Llewellyn in 900. Cadell, a third son, who had inherited the south-west kingdom of Seisyllwg by virtue of Rhodri’s marriage to a princess of that kingdom named Angharad must, it seems, have acquired Dyfed too before his death in 909, wresting control from the native kings of Ceredigion. His sons Hywel (who appears to have married the last princess of Ceredigion) and Clydog seem to have jointly inherited control of Seisyllwg and Dyfed and, therefore, of the major Welsh cult centre at St David’s. The three cousins jointly submitted to Eadweard in 918 or 921, continuing their alignment with the dynasty of Ælfred.

There is no further record of Norse military activity against the Welsh kingdoms before 954; now a long period of consolidation in the hands of a single dynasty and active co-operation with the kings of Wessex and Mercia allowed the grandsons of Rhodri to play their own parts in the grand political circus of tenth-century Britain.

*

The grandsons of Ívarr had reconquered Dublin and wrested control of its sister city, York, after 918. Dublin now underwent rapid urban expansion under one Guðrøðr, either a cousin or brother of Rögnvaldr and Sigtryggr. In 919 the latter departed from Dublin ‘through the power of God’, according to an unhelpful entry in the Annals of Ulster. The next we hear of him, he had joined the impious Rögnvaldr in York. In 919, according to a retrospective entry in the Northumbrian annal known as the Historia Regum,∆ Rögnvaldr ‘broke into York’. The arrival of his cousin the following year might be seen either as a request for support or a sibling coup; the same annal is the only source to mention Sigtrygg’s raid on Cheshire. The treaty with Eadweard, of the same year, reinforces the idea that these ambitious Norse kings were content, for the moment, to consolidate their position.

Rögnvaldr died, according to the Annals of Ulster, in 921, succeeded immediately by Sigtryggr. Rögnvald’s short reign is evidenced in a series of coins: just twenty-three examples have survived, minted at York in those two years; but the numismatist Mark Blackburn estimated from these few survivals that more than fifty dies had been produced for the Norse king, from which many hundreds, if not thousands, of coins must have been struck.12 One set carries a rare bust on the reverse, with an odd Karolus monogram deriving from originals of Charles the Simple (897–922) in Francia; another carries an image of a drawn bow and arrow on the obverse, with either Thor’s hammer or a Tau cross on the reverse: an idolater he may have been, but Rögnvald’s sensitivities to the propaganda potential of ambiguous military/Christian and imperial iconography on his coins suggests a man of greater subtlety and creative energy than his enemies would wish us to know.

Both before and after Rögnvaldr the coinage produced by Northumbrian kings is dominated by so-called St Peter issues, first appearing in about 905 and then continuing under Sigtryggr. A total of nearly 300 coins has been retrieved so far from hoards and single finds, representing more than 100 dies. These carry the name not of the king but of the city, as EBRAICE or EBORACE CIVITAS, together with the inscription SCI PETRI MO (Sancti Petri moneta) on the reverse. In form they are derivative of coins produced by Ælfred and Eadweard.13 The earlier issues carry a cross on one side; after Rögnvaldr they tend to be accompanied by a sword or hammer. Stylistically and ideologically they have affinities with the St Eadmund and St Martin coin series of East Anglia and Lincoln, and there is a strong temptation to suggest, as David Rollason argues, that these are ecclesiastical issues of the archbishops of York in their roles as economic tsars.14

A counter-argument is proposed by the numismatist Mark Blackburn, who believes that there is no evidence of large-scale coin production in Europe in this period outwith the fiscal control of kings.15 It is clear that, either way, York was an active and productive economic hub from which the twin faces of the state, secular and spiritual, were apparently doing rather well in the first quarter of the tenth century. But numismatists also detect, in a lack of innovation in the St Peter series and in their continuing decline in weight and literacy, an economy that was beginning to stagnate, either because of instability in the ruling establishment or because of Eadweard’s success in reviving the southern economy, drawing trade and production towards Wessex and Mercia—where Æðelflæd’s revival of Chester led to the establishment of a flourishing mint, pottery production and vigorous trade.

*

Eadweard seems to have made no further attempt, after 921, to penetrate deeper into the Anglo-Scandinavian North. A complete absence of entries in the Wessex Chronicle for three years has suggested to some historians that the king’s health, or at least his martial energy, was in decline. There is no evidence that Lincoln or the old kingdom of Lindsey had fallen to Eadweard’s armies by the end of his reign; Northumbria lay outside his control and, perhaps, beyond his ambitions.

In his last years, as befitted a king in his late forties, dynastic concerns needed to be addressed. Eadweard had married three times. With his first wife, Ecgwynn, he had a son, Æðelstan, and a daughter, perhaps called Ealdgith.** William of Malmesbury maintained a tradition that Æðelstan was raised in fosterage at the royal court in Mercia;16 if so, the implication, against William’s own partisan testimony, is that he was meant to succeed there as his father’s regent, in preference to Æðelred’s and Æðelflæd’s daughter Ælfwyn. A Frankish and possibly Insular tradition, that only sons born to a king after his succession were regarded as eligible for the kingship, may have precipitated Eadweard’s desire to remarry after Ælfred’s death in 899 and produce an heir more acceptable to West Saxon propriety.

Ecgwynn was either dead or had been repudiated by 901, by which time the new king had married Ælfflæd, probably a daughter of Æðelhelm, the ealdorman of Wiltshire.†† She bore eight children. Her eldest son, Ælfweard, seems to have been intended as Eadweard’s heir in Wessex. By 920 she had apparently ‘retired’ to the monastic life in a foundation at Wilton17 and Eadweard married for a third time. His new bride, Eadgifu, was the politically expedient daughter of Sigehelm, ealdorman of Kent, a key ally in the south-east. She bore at least two sons, both of whom would ultimately succeed to the kingship, and two daughters. At Eadweard’s death neither of those sons, Eadmund or Eadred, was old enough to be seriously considered for the West Saxon throne.

A large family presented challenges and opportunities. Royal princesses, potentially wielding considerable personal power and wealth (the examples of Cwenðryð, at the turn of the ninth century, Ælfred’s daughter Æðelflæd and Eadweard’s third wife Eadgifu are prominent) were also political commodities to be deployed as capital by their fathers, brothers and sons. From the seventh century it had been the practice of the earliest Christian kings of Northumbria to gift daughters (and sisters) to the church and to endow them with large estates from which they could implement dynastic policy via extensive networks of patronage. Princesses were often married to dynasts from other kingdoms and, in the diplomatic pecking order established time out of mind among the European Christian states, the gift of a royal princess as a bride generally indicated submission to the prospective father-in-law. King Offa of Mercia had managed to outrage Charlemagne by offering his son Ecgberht as a spouse to the Frankish king’s daughter, Bertha, and suffered a trade embargo as a result. However, when Ælfred married his daughter Æðelflæd to his ‘godson’ Æðelred, ealdorman of Mercia, it was evidently seen as an act of political superiority; while another daughter, Ælfðryð, dispatched to become the bride of Baldwin II, count of Flanders, may have been a diplomatically neutral bride.

In that light, the Wessex regime’s disposition of Eadweard’s daughters is significant. By the end of his reign he had made substantial diplomatic progress on the Continent. His grandfather and uncle had notoriously both been married to Judith, the daughter of Charles II the Bald. By about 919 Eadweard had sent Eadgifu, the second of his daughters by Ælfflæd, to the court of Charles III the Simple, the forty-five-year-old posthumous son of Louis the Stammerer. Two others, Eadflæd and Æðelhild, ‘renounced the pleasure of earthly nuptials’, according to William of Malmesbury’s account: the former to take holy orders and the latter in a lay habit.18 Eadweard’s third wife, Eadgifu, saw one of her daughters married off to a more or less eligible Continental, Louis of Aquitaine, while the other was ‘dedicated to Christ’. So high was the current stock of the West Saxon dynasty that Eadweard’s ultimate successor, the perhaps unlikely Æðelstan, was able to distribute the royal gift of his other half-sisters, Eadhild and Eadgyð, respectively to Hugh the Great, count of Paris and duke of the Franks, and Otto I, duke of Saxony and future Holy Roman Emperor.

William of Malmesbury elaborates on the splendour of the embassy through which Hugh, hearing of Eadhild’s incomparable beauty, sought her hand in 926:

The leader of this embassy was Adelolf, son of Baldwin, count of Flanders, by Ælfðryð, [sister of] King Edward. When he had set forth the wooer’s requests in an assembly of nobles at Abingdon, he offered indeed most ample gifts, which might instantly satisfy the cupidity of the most avaricious: perfumes such as never before had been seen in England; jewellery, especially of emeralds, in whose greenness the reflected sun lit up the eyes of the bystanders with a pleasing light; many fleet horses, with trappings.19

The list goes on to include the sword of Constantine the Great, on whose pommel an iron nail from the True Cross was fixed. How could the princess’s brother refuse?‡‡

Historians are rightly sceptical of this account, which aims to exalt William’s biographical subject, Æðelstan. But such magnificent objects were to be found at the West Saxon court. One of them survives, improbably. A very rare and splendidly embroidered stole and maniple, recovered from St Cuthbert’s coffin in 1827 and now conserved at Durham Cathedral, carry inscriptions which indicate that they were commissioned by Eadweard’s second wife, Ælfflæd, and intended for her ‘pious bishop Friðestan’, bishop of Winchester between 909 and 931. Narrow vertical bands contain figures of the Old Testament prophets, of St James and St Thomas the Apostles, of Gregory the Great and the Lamb of God, among sprays of acanthus leaves and pairs of beasts. Analysis by Elizabeth Plenderleith in the 1950s showed that the designs were stitched on to fine tabby weave silk, using varieties of coloured silk stitching including gold thread.20 If such wonders were intended to grace the shoulders of favoured bishops, it cannot be doubted that the West Saxon court enjoyed access to very high levels of technology and craftsmanship (and craftswomanship), not to mention exotic raw materials from the East. How they came into the possession of the Cuthbert community at Chester le Street is another matter.§§

Such interactions at the highest level allow us to picture frequent contact between courts as envoys passed to and fro with news, offers, gifts and intelligence of mutual benefit. Kings took a keen interest in trade, as evinced by Offa’s sometimes fraught relations with Charlemagne and by the arrival of notable travellers to the court of Ælfred. Frankish influences on Insular pottery and coinage (Rögnvald’s Karolus monogram, for example) and possibly on ecclesiastical architecture, as well as dress style and more intellectual pursuits, along with periodic pressure for ecclesiastical reform from Rome, were in cultural competition with closer and more obvious influences travelling west, east and south from areas under Scandinavian control.

Eadweard may not have been as sensitive as his father to the values of literature, philosophy and education; but he knew political advantage when he saw it and proved himself capable of exploiting opportunities as they arose. The Æðulfings of the tenth century were nothing if not well connected and, increasingly, they were drawn into the complex, not to say Byzantine, affairs of the fragmenting Frankish kingdoms.

*

The silence of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle during Eadweard’s last years can be read in a number of ways, the least probable of which is that there were no significant events to record. Impending regime change may have induced caution in the chronicler of Winchester; the court’s intellectual energy might have turned to lassitude with the decline in the king’s health and vitality after his twenty-five years’ rule. The only hint of political trouble that shows on the surface is a note in the often unreliable account provided by William of Malmesbury, drawing on sources now lost, indicating that Eadweard, ‘a few days before his death, subdued the contumacy of the city of Chester, which was rebelling in confederacy with the Britons’.21

All versions of the Chronicle for the year 924 agree that Eadweard died at Farndon-on-Dee, 8 or so miles (13 km) south of Chester, on the Mercian–Welsh border. The location suggests that William’s account has merit. Whatever tensions were now emerging at the West Saxon court may have been transmitted to vulnerable borderlands where British, Scandinavian and native interests were held in fragile balance by the perceived strength of Eadweard’s formidable, but now ageing, military machine.

The Winchester Chronicle is terse: ‘In this year passed away Eadweard, and Æðelstan, his son, came to the throne.’22 As it stands, that will not do, because the ‘D’ and ‘C’ (Mercian Register) variants offer significant additional detail:

King Eadweard died at Farndon-on-Dee in Mercia; and very soon, sixteen days after, his son Ælfweard died at Oxford; they were buried at Winchester. Æðelstan was accepted as king by the Mercians.23

The Historia de Sancto Cuthberto, with finely tuned hindsight, continued its running commentary on the fortunes of the Chester le Street community’s future sponsors:

At that time King Eadweard, full of days, and worn down by ripe old age, summoned his son Æðelstan, handed his kingdom over to him, and diligently instructed [him] to love St Cuthbert and honour him above all saints, revealing to him how he had mercifully succoured his father King Elfred [Ælfred] in poverty and exile.24

Æðelstan’s supposed fostering at the Mercian court## gave him solid support among his aunt’s ealdormen. Winchester and the West Saxon court were, it may be inferred, more or less solidly behind Eadweard’s chosen heir Ælfweard. Had he not died so soon after his father, there must have been a very real possibility of Eadweard’s recently consolidated kingdom dividing on historical and regional lines; even of a civil war. That Æðelstan was not immediately accepted by the West Saxons seems likely from the delay in his inauguration, which took place at Kingston upon Thames a year later, and from the exclusively Mercian witnesses to his first charter issued in 925.25 Kingston looks like a suitably diplomatic site, on the Wessex–Mercian border at the headway of the Thames and the place where his father had been inaugurated. It was a very obvious statement of legitimacy.

If William of Malmesbury is to be believed, an objection had been raised that Æðelstan was ‘born of a concubine’—in other words, that since his mother had been married to Eadweard before his assumption of the throne, he was ineligible because she was not then the wife of a king. One detects factionalism beneath the smoothly flowing narrative of the Chronicle: indeed, that smooth flow was substantially choked off between 924, the year of Eadweard’s death, and 931, when the Winchester Chronicle sees its first entry for seven years. On his own death in 939 Æðelstan was not buried with his father and half-brother at Winchester but at Malmesbury Abbey (hence, perhaps, William’s partisan treatment of him). In any event, a potential West Saxon rebellion failed to materialize∫∫ and Æðelstan succeeded to Wessex, West Mercia, and those lands which had been won from Danish Mercia and East Anglia.

Æðelstan’s inauguration ceremony at Kingston affords a rare glimpse of contemporary conceptions of kingship at first hand. He styled himself rex Saxonum et Anglorum, according to a charter issued on that same day, 4 September 925.26 The formal benediction ceremony has been preserved in a text known as the Second Coronation Ordo.ΩΩ He seems also to have been presented with crown (a Frankish-influenced departure from earlier Insular use of the more martial helmet), ring, rod and sceptre by the new archbishop of Canterbury, Æðelhelm. The king’s responsibilities towards Christianity (represented by the ring), towards widows, orphans and the destitute (the sword) and to ‘soothe the righteous and terrify the reprobate’ (the rod) were given material form. There are references to the two united peoples (West Saxons and Mercian Angles) whom he had been ‘elected’ to rule, and a solemn prayer that the king would ‘hold fast the state’.27

Æðelstan’s sensitivity to his split loyalties, which would extend to the inclusion of Danish nobles among his household and to active diplomatic engagement with Anglo-Scandinavian York, may find remarkable expression in the greatest Anglo-Saxon poem. The single surviving manuscript of Beowulf, that Dark Age epic of monster and exiled prince, of loyalty, brotherhood and much more besides, dates to around the year 1000. The combined research of hundreds of scholars and poets has reached no firm conclusion about its origins, transmission, date or provenance. In current thought the first transcription of a legendary poetic form, whose origins lie somewhere in the era of pagan Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian, Germanic and early Irish Christian myth, must have taken place some time in the eighth century. It survived by oral or written transmission, or both, until the two scribes whose work survives fossilized it in a single monumental form.

Æðelstan’s biographer Sarah Foot makes a case that at least one transcription and evolution of the poem occurred during the reign of Æðelstan, when it would have provided a unique multi-cultural expression of common origins.28 One might add to her argument that the martyred seventh-century Northumbrian King Oswald, a recent favourite at Gloucester and at the Mercian court, has been proposed as the epitome for righteous exiled princes—not least by J. R. R. Tolkien, who deployed Oswald as a prototype for his fictional returning king in the Lord of the Rings.29 As a king with his own split loyalties, an Oswald obsession and a demonstrable love of poetry, Æðelstan is a good candidate for propagating Beowulf among an increasingly literate audience trying to make sense of its own innate affinities with ambiguity.

The new king lost little time in entering the diplomatic and political fray, deploying the immense political and military capital accumulated by his father, aunt and grandfather. More than thirty years old and schooled in the politics of Anglo-Scandinavian relations by the expert dynasts of the West Saxon ruling house, Æðelstan’s political maturity is evident from the start. By the end of 926 he had received the Continental embassy which resulted in the dispatch of his half-sister Eadhild to the marriage bed of Hugh, count of Paris and duke of the Franks.

Æðelstan had already, earlier that same year, contracted a union of potentially greater significance: the ‘D’ Worcester version of the Chronicle records that ‘King Æðelstan and Sigtryggr, king of Northumbria, met at Tamworth on 30 January and Æðelstan gave him his sister in marriage.’30 Tamworth was the Mercian royal burh where Æðelflæd had died and where a 1913 statue of her≈≈ stands close by the walls of the later medieval castle. Tamworth (Tomworðig: ‘enclosure by the River Tame’) lay on a tributary of the upper Trent river system and was the caput of an early regio or petty kingdom. Its natives, the Tomsæte of the Tribal Hidage, had been absorbed into the Mercian overstate by the eighth century, from which time it became a favourite royal residence and possible minster foundation, close to the principal Mercian see at Lichfield and to Watling Street, less than 2 miles (3 km) to the south. During the annexation of much of Mercia by Scandinavian armies in the 870s, Tamworth may have fallen under Danish authority; but it acted as a sort of offensive border garrison for West Mercian forces after Æðelflæd constructed a new fortress here in 913.

Tamworth is celebrated among archaeologists for its Anglo-Saxon water mill complex, excavated by Philip Rahtz and Roger Meeson in two campaigns in the 1970s. It stood on the north bank of the River Anker, close to its confluence with the Tame and to the south-east corner of the later burh defences.31 The second of two successive horizontal paddle mills on the site, providing a rich and invaluable insight into the sophistication of Early Medieval civil engineering (including, for example, the survival of a high-quality steel bearing from the wheelhouse), has been dated by its well-preserved timbers to about 855. Its late ninth-century destruction by fire might plausibly, but with caution, be laid at the door of the mycel here. Eadweard’s immediate occupation of the burh on his sister’s death indicates its continuing symbolic and strategic importance. Æðelstan established a mint here, and his choice of Tamworth as a venue for a royal wedding and diplomatic alliance echoes his own political affinities as much as it does the convenience of a border town for inter-kingdom negotiations.

The grandson of Ívarr who married the king’s sister in 925 may or may not have been aware that for the Angelcynn such a marriage transaction implied political submission. He may have seen it as an alliance of equals, and the Chronicle affords him the title of king. Whatever the case, his apparent enthusiasm for a rapprochement with the southern English kingdoms, and the implication that he must have been baptized in order for his marriage to be consecrated, indicates a greater willingness to make accommodations with native culture than his cousin Rögnvaldr had shown. So too does his readoption of the St Peter coinage in York and, perhaps, Lincoln. His wife’s fate is not known; nor, oddly, is her name.

How Sigtrygg’s reign might have played out over the next decade cannot now be established: he was dead within a year.32 He was immediately succeeded by the most aggressive of the grandsons of Ívarr, that Guðrøðr who had imposed his military rule on Dublin so effectively after 921, who had plundered the Patrician cult centre at Armagh and more recently attacked Limerick, according to the Annals of Ulster. But his attempted coup at York was swiftly countered by Æðelstan and by the end of 927 he had returned to Dublin.∂∂ The Worcester version of the Chronicle records Æðelstan’s ‘annexation’ of Northumbria in the aftermath of Guðrøð’s expulsion. In this fortuitous and expedient series of events one can, perhaps, detect a step-change in Æðelstan’s thinking about Northumbria: from dangerous enemy to dynastically entwined ally, to its potential absorption into his kingdom. Now he marshalled military, political and cultural forces behind the project; but, despite later historians’ wishful thinking, the fall of York did not fire the starting gun on a race towards the unification of England; and it could not.

44. PLACE NAMES on a signpost in the East Riding of Yorkshire: ‘telltale suffixes like –by and –Thorpe testify to the presence of Norse speakers’.

Early Medieval kingship relied on the preservation and expansion of networks of patronage constructed across generations. The kings of Wessex owned large estates spread across the southern shires, from Kent to Devon, accumulated by their forbears. Æðelstan was able to expand his portfolio by right of succession to Æðelred and his aunt Æðelflæd—although those estates seem to have been confined to lands in Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, the ancient territories of the Hwicce where Æðelred’s line had once probably been kings in their own right.ππ There is almost nothing from further north; nothing in the Mercian heartlands around Tamworth and Lichfield—we do not know in whose portfolio they lay.

Some of the kings’ wealth in the south had been alienated by grants, as bookland, to the great minsters and to ealdormen and thegns, ensuring their support and spiritual protection and spreading the munificence of the king. Some of that land had returned to the king’s portfolio through lapses in ownership, legal forfeit and the fallout from the heyday of the Viking armies. The remainder was often distributed by Æðelstan in rebuilding the fortunes of those southern churches that he so conspicuously favoured. But he was not the only great landowner, and even with sceptre and rod in hand and a crown on his head, he must negotiate power with others who held it. As the machinations of the community of St Cuthbert show, the manipulation of grants was a subtle, complex affair. Tenth-century politics rarely consisted of the simple military arrogation of rights to land: it required the conversion of capital into power by exploiting webs of obligation and gift which, like the root systems of trees, lie substantially obscured and hidden from us. Even when they are exposed to our limited view, we never get to see the whole picture.

The fragmentation and theft of estates that had occurred in areas of Scandinavian control, the collapse of episcopal and minster administration and the inability of the southern kings to access those lines of patronage meant that in East Mercia and Lindsey, in East Anglia and Northumbria, even if the king’s writ ran, his ability to manipulate landholdings to buy favour and support was limited in the extreme. Those networks would have to be built from scratch, accumulated through military victory or bought with hard cash.∆∆ Two grants of Eadweard, confirmed by Æðelstan, show that the West Saxon kings were active in the business of acquiring and strategically deploying estates in key areas along and across the border with Danish Mercia.*** Now, those techniques needed to be implemented on a vastly grander scale, over a much longer period.

How, then, was Æðelstan to bring the North into the orbit of an expanded Wessex? The Worcester version of the Chronicle offers one clue in its extended entry for 926, properly 927:

He brought into submission all the kings in this island: first Hywel, king of the West Welsh, and Constantín, king of Scots, and Owain, king of Gwent††† and Ealdred Eadulfing from Bamburgh. They established a covenant of peace with pledges and oaths at a place called Eamont Bridge on 12 July: they forbade all idolatrous practices, and then separated in accord.33

The historian is wisely sceptical of such one-sided accounts, especially when there is no surviving record from any of the other participants. But the Worcester Chronicle embeds a more northern perspective than the Winchester prototype, which is absolutely silent in these years; and in any case the location and form of these ceremonial ‘submissions’ is telling.‡‡‡ Eamont Bridge can be identified: just south of Penrith on a narrow spur of land between two rivers, the Eamont and Lowther. Roman roads run north to south and east from here (including the A66 trans-Pennine route towards Stainmore). The Roman fortress and later medieval castle of Brocavum, or Brougham, occupies a strategically important site close by at the rivers’ confluence and, just to the west, an impressive henge monument speaks of a landscape steeped in symbols of earthly and unearthly power. More importantly, Eamont Bridge lay in an area that had once formed part of the British kingdom of Rheged and had fallen under Northumbrian control by the end of the sixth century. That control had lasted perhaps 100 years; in Æðelstan’s time it seems as though the region was disputed between the kings of York and Strathclyde, with the possible territories of Dublin Norse abutting it to the south. Æðelstan’s confidence and military capability was such that he was able to conduct peace negotiations on his antagonists’ patch or, at least, on their borders.

This was a landscape of pastoralists living in widely dispersed settlements with nothing like a burh for several days’ travel in any direction. Carlisle may have retained some minster functions and perhaps a harbour; a monastery existed just to the west of Penrith at Dacre, where four enigmatic, distinctly Anglo-Scandinavian stone bears guard the compass points of the church; and contemporary sculpture has been retrieved from Penrith itself. This was by no means an empty landscape; but so far as royal power was concerned it may have constituted neutral territory: a debatable land. This was a meeting of wary neighbours, not a surrender, and it follows an established pattern of siting what, these days, would be called political summits on frontiers.34

The oaths and pledges recorded in the Chronicle must have been supplemented by the exchange of royal, or at least noble, hostages as guarantors of that peace. Æðelstan will have swelled the coffers of his treasure chests with tribute; and with fresh cash assets he was in a better position to purchase rights to land beyond his homeland. The treaty signed at Eamont looks like a repeat of the ‘status quo’ agreement which had pertained under Eadweard from 920, reinforced by the dynastic marriage between Æðelstan’s only full sister and Sigtryggr. But Æðelstan’s hand had been considerably strengthened by Sigtrygg’s death and by the timely departure of Guðroðr to Dublin.

The significance of the renunciation by all participants of idolatrous practices, apparently aimed at those with Norse affiliations, is unclear. No Scandinavian king was present, so far as the Chronicle was concerned, so one suspects the presence of a number of jarls with authority over parts of the kingdom of York or of East Mercia, acting as local regents to Æðelstan’s undeniable overlordship.

A poet, seemingly present at the event and acting in semi-official capacity as a correspondent embedded within the king’s entourage, has left some lines of verse for historians to chew on. The Carta dirige gressus, as it is known from its first line, survives in two manuscripts. One, curiously, is an eighth-century gospel book, probably produced at Lindisfarne, which was in the possession of the St Cuthbert community at Chester le Street in the tenth century.35 The poem was copied on to the lower margin of a page some time in the late tenth or early eleventh century. That a scribe at Chester le Street was interested in composing or copying a laudatory poem concerning Æðelstan is not surprising.§§§ The verses, in six stanzas, have been convincingly dated to the immediate aftermath of the Eamont peace treaty by Michael Lapidge, the scholar of medieval Latin literature who has made a special study of poetry in the reign of Æðelstan.

Carta, dirige gressus

per maria navigans

tellurisque spacium

ad regis palacium.

Letter, direct your steps

Sailing across the seas

And an expanse of land

To the king’s burh.36

The poem directs itself to the queen, the prince, distinguished ealdormen and arms-bearing thegns ‘whom he now rules with this Saxonia### [now] made whole∫∫∫ [perfecta]: King Æðelstan lives glorious through his deeds’. The poet, who helpfully records his own name, Peter, in the last stanza, goes on to versify the death of Sigtryggr and the arrival of Constantín, eager to display his loyalty to the king, securely placing the poem in the context of the events of 927. He ends with a prayer that the king might live well and long through the Saviour’s grace. Michael Lapidge argues that the poem acted as a sort of headline dispatch to the court at home, a Neville Chamberlain-like brandishing of a treaty. He also argues that the court in question must be Winchester; but, given the hostility of that burh and its minster to Æðelstan’s regime, I wonder if Gloucester was its intended destination: a royal possession very much more closely affiliated to the king and his interests.

One minor problem concerns the identity of the queen, one of the poet’s addressees. Æðelstan, conspicuously, had not married and would not marry or produce any children, legitimate or otherwise. ΩΩΩ The queen concerned must, I think, be the mother of the prince addressed in the same line: that is to say, Eadweard’s third wife Eadgifu, whose sons Eadmund and Eadred would succeed their half-brother, Æðelstan, in due course and who herself died after 966.≈≈≈ The shadowy influence of that interesting woman surfaces from time to time in the middle of the tenth century, a reminder that political power could be exercised by means more subtle than the king’s army or even that of the poet’s hand.

If Æðelstan could not yet unify all the peoples of the island under his governance he could at least use the time-worn tools of the propagandist’s quill to spread the message that all was well in Saxonia under his God-given rule. By 930 the king’s moneyers, whose message penetrated deeper and more widely than those of the versifier, were portraying him wearing a crown and styled REX TOTIUS BRITANNIÆ.

Æðelstan’s pretensions to supremacy over the whole island of Britain, and apparent desire to take his place on the list of Bretwaldas, those who had anciently wielded imperium over the whole island of Britain, feed into a well-rehearsed narrative of English unification and supremacy, etched onto the dies of his coinage and inscribed in the lists of those who witnessed his laws and gifts. It is superbly ironic that of all the sources available to us for his reign, the coins and charters should also most convincingly undermine those claims.

* See map, p. 322

† See above, p. 124.

‡ It is just possible that Eardwulf and Eadwulf are the same person, i.e. the father of Ældred.

§ I am particularly grateful to fellow members of the Bernician Studies Group for a discussion of the three relevant passages in the HSC: 22–24.

# As an aside, I am drawn to the ‘Mercian’ response to large-scale twentieth-century immigration from Asia, one of the many fruits of which was the invention of the Balti dish whose popularity expresses an affinity with ambiguity every bit as ironic as those of the Coppergate artisans of tenth-century York.

∫ The seizure of the property of a debtor.

Ω II Eadweard; the date range is suggested by Simon Keynes. Keynes 2001, 58. The code contains just eight clauses; an adjunct to the codes promulgated by earlier West Saxon kings rather than a replacement.

≈ Mersey is ‘boundary river’ in Old English.

∂ Traditionally the burh and bridge have been placed at the well-known Trent Bridge crossing. Archaeologist Jeremy Haslam has proposed a site further to the west at Wilford, partly protected by a broad meander of the river and close to a settlement focused on St Wilfred’s church; Haslam 1987.

π Also known as the church of the Culdees, possibly ‘Companions of God’, an extreme ascetic, communal movement seeming to originate in Ireland. Woolf 2007, 314.

∆ A long-awaited modern edition with an English translation, by the eminent Durham historian David Rollason, is to be published shortly. The Historia Regum was compiled at Durham in the twelfth century but contains a miscellany of earlier material, including otherwise unknown regional annals.

** Sometimes associated with St Edith of Polesworth.

†† She witnessed a charter of that year (S363) as coniunx regis.

‡‡ The embassy is dated to 926, the second year of Æðelstan’s reign, by Flodoard of Rheims. Foot 2011, 47.

§§ See below, Chapter 10.

## William of Malmesbury’s testimony is supported by a grant of privileges from the new king to Æðelred’s and Æðelflæd’s minster, St Oswald’s in Gloucester, in the year of his succession. Foot 2011, 34.

∫∫ William of Malmesbury relates the story of an attempted coup by the otherwise unknown Ælfred, who tried to blind the new king at Winchester and who subsequently fled to Rome, where he died. EHD Secular narrative sources 8. Whitelock 1979, 303.

ΩΩ Debate continues about whether its first use was Eadweard’s, Æðelstan’s or, indeed, Edgar’s inauguration. Foot 2011, 75ff. Janet Nelson’s convincing arguments in a recent paper carry the day, so far. Nelson 2008.

≈≈ Commissioned to mark the millennium of her construction of the burh here. She is depicted in modest robes with her arm around a youthful nephew, Æðelstan (see p. 271).

∂∂ He may not even have got so far as York. Symeon, Historia Regum, reports his expulsion from the kingdom of the Britons, i.e. Cumbria. Charles-Edwards 2013, 521.

ππ Many of the south Mercian charters which attest such estates are, in any case, under a cloud of doubt regarding their authenticity. Foot 2011, 135.

∆∆ See below, Chapter 11: the Amounderness purchase. The matter of Æðelstan’s cash wealth and estates is treated fully in Foot 2011, 148ff.

*** See above Chapter 8, p. 301.

††† Most historians think that this is an error for Owain of Strathclyde; but there was a possibly contemporary king of Gwent named Owain, and it is possible that both kings were originally meant. Charles-Edwards 2013, 512.

‡‡‡ I am inclined to discount William of Malmesbury’s lurid, expanded version in which Guðroðr flees to Scotland and Æðelstan slights the defences of York and loots the city. But it is worth reading for the possible insider information on which William may be elaborating. EHD : Whitelock 1979, 307.

§§§ See below, Chapter 10.

### Lapidge, I think significantly, translates Saxonia as ‘England’. The poet is implying a united kingdom, ‘made whole’, of the Saxons. The lands of the Angles – that is, in the east and north, are seemingly excluded.

∫∫∫ Perhaps more correctly ‘complete’.

ΩΩΩ The Æðida cited in Liber Eliensis III.50 as a daughter of Æðelstan looks suspiciously like an error for a sister, perhaps that otherwise unnamed sister given in marriage to Sigtryggr. Fairweather 2005, 356.

≈≈≈ The last date on which she appears as a charter witness.