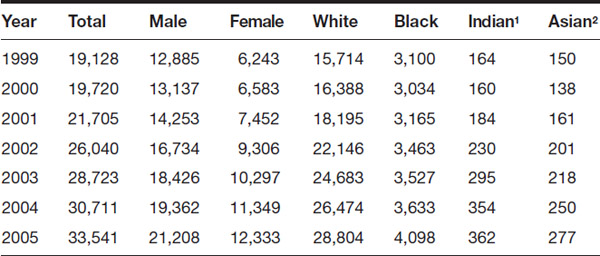

Table 5.1 Drug-Induced Deaths, 1999–2013

An overview of the way in which the United States and other nations have tried to deal with substance abuse problems can be found by reviewing important documents related to the issue. This chapter contains examples of laws, treaties, reports, court cases, and other documents associated with one or another aspect of substance abuse. The chapter also provides data and statistics on the extent and effects of substance abuse.

| Schedule | Examples |

I |

Heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana, mescaline, methaqualone, morphine, peyote, psilocybin |

II |

Amphetamine, cocaine, codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, meperidine, methadone, methamphetamine, morphine, opium and its extracts, phencyclidine (PCP) |

III |

Anabolic steroids (including testosterone and derivatives), barbituric acid derivatives (“barbiturates”), some codeine and hydrocodone products, ketamine, lysergic acid |

IV |

Alprazolam (Xanax), Chlordiazepoxide (e.g., Librium), chloral hydrate, diazepam (e.g., Valium), meprobamate (e.g., Miltown), phenobarbital (e.g., Luminal), zolpidem (e.g., Ambien), zopiclone (e.g., Lunesta) |

V |

Codeine and derivatives preparations, diphenoxylate preparations (e.g., Lomotil), opium preparations (e.g., Parapectolin) |

Source: “Controlled Substances Schedule.” 2016. Office of Diversion Control. Drug Enforcement Administration. U.S. Department of Justice. http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/. Accessed on July 6, 2016.

Probably the first effort by the U.S. government to exert some control over the production, distribution, and consumption of recreational drugs was the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914. Although this act did not make the drugs with which it dealt—opiates—illegal, it did place a tax on their production, distribution, and sale. In retrospect, the Harrison Act was a weak effort to control substance abuse, but it is historically significant because of its being the first attempt to interrupt substance abuse in any way whatsoever by the federal government. The core of the act is expressed in its first section, reproduced here.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that on and after the first day of March, nineteen hundred and fifteen, every person who produces, imports, manufactures, compounds, deals in, dispenses, distributes, or gives away opium or coca leaves or any compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, or preparation thereof, shall register with the collector of internal revenue of the district, his name or style, place of business, and place or places where such business is to be carried on: Provided, that the office, or if none, then the residence of any person shall be considered for purposes of this Act to be his place of business. At the time of such registry and on or before the first of July annually thereafter, every person who produces, imports, manufactures, compounds, deals in, dispenses, distributes, or gives away any of the aforesaid drugs shall pay to the said collector a special tax at the rate of $1 per annum: Provided, that no employee of any person who produces, imports, manufactures, compounds, deals in, dispenses, distributes, or gives away any of the aforesaid drugs, acting within the scope of his employment, shall be required to register or to pay the special tax provided by this section: Provided further, That officers of the United States Government who are lawfully engaged in making purchases of the above-named drugs for the various departments of the Army and Navy, the Public Health Service, and for Government hospitals and prisons, and officers of State governments or any municipality therein, who are lawfully engaged in making purchases of the above-named drugs for State, county, or municipal hospitals or prisons, and officials of any Territory or insular possession, or the District of Columbia or of the United States who are lawfully engaged in making purchases of the above-named drugs for hospitals or prisons therein shall not be required to register and pay the special tax as herein required.

Source: Public Law No. 223, 63rd Cong. Available at Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. http://druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/e1910/harrisonact.htm. Accessed on July 3, 2016.

On December 17, 1917, the U.S. House of Representatives took the first step in amending the U.S. Constitution to prohibit the use of alcoholic beverages in the United States. The U.S. Senate approved the same act the following day. The proposed amendment was then submitted to the separate states, where it was finally approved by the required number of states (36) on January 16, 1919. Ultimately, only two states defeated the proposed amendment: Connecticut and Rhode Island. On January 26, 1919, Acting Secretary of State Frank L. Polk certified adoption of the amendment. The amendment did not specifically prohibit the use of alcoholic beverages in the United States, although it made it very difficult to obtain such beverages legally. The text of the amendment is as follows.

Amendment XVIII

Source: Charters of Freedom, National Archives.

After more than a decade of Prohibition in the United States, many people were convinced that the great experiment to control the use of alcohol in this country was a failure. In response to that feeling, the U.S. Congress on February 20, 1933, adopted an act initiating the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment by the adoption of a new amendment to the Constitution, the Twenty-First Amendment, which abrogated the earlier amendment. On December 5, 1933, the 36th state, Utah, ratified the amendment, and it was certified on the same date. Only one state, South Carolina, rejected the proposed amendment, although eight other states never took action on the amendment. The text of the amendment is as follows.

Amendment XXI

Source: Charters of Freedom, National Archives.

The first significant government report on the health effects of smoking—Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service—was issued in 1965. The report had a significant impact on the general public, on advocacy groups opposed to smoking, and on lawmakers. One direct result of the report was the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965, which was later amended a number of times. The provisions of the original law and later amendments are now part of the U.S. Code, at Title 15, Chapter 36. A note about the 1984 amendment is included in the following excerpt.

It is the policy of the Congress, and the purpose of this chapter, to establish a comprehensive Federal Program to deal with cigarette labeling and advertising with respect to any relationship between smoking and health, whereby—

Section 1332 provides definitions for a number of terms used in the act.

The core of the bill is found in Section 1333, which provides, in part, that:

This section continues with more detailed instructions about the precise nature of the labeling to be used.

In 1984, the original act was amended to change the wording required on all cigarette packages. The new ruling required the use of one of the four following statements:

Source: U.S. Code, Title 15, Chapter 36, Sections 1331 and 1333.

The cornerstone of the U.S. government’s efforts to control substance abuse is the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, now a part of the U.S. Code, Title 21, Chapter 13. That act established the system of “schedules” for various categories of drugs that is still used by agencies of the U.S. government today. It also provides extensive background information about the domestic and international status of drug abuse efforts. Some of the most relevant sections for the domestic portion of the act are reprinted here.

Section 801 of the act presents Congress’s findings and declarations about controlled substances, with special mention in Section 801a of psychotropic drugs.

The Congress makes the following findings and declarations:

The Congress makes the following findings and declarations:

Section 802 deals with definitions used in the act, and section 803 deals with a minor housekeeping issue of financing for the act. Section 811 deals with the attorney general’s authority for classifying and declassifying drugs and the manner in which these steps are to be taken. In general:

§ 811. Authority and criteria for classification of substances

The Attorney General shall apply the provisions of this subchapter to the controlled substances listed in the schedules established by section 812 of this title and to any other drug or other substance added to such schedules under this subchapter. Except as provided in subsections (d) and (e) of this section, the Attorney General may by rule—

…

Section (b) provides guidelines for the evaluation of drugs and other substances. The next section, (c), is a key element of the act.

In making any finding under subsection (a) of this section or under subsection (b) of section 812 of this title, the Attorney General shall consider the following factors with respect to each drug or other substance proposed to be controlled or removed from the schedules:

Section (d) is a lengthy discussion of international aspects of the nation’s efforts to control substance abuse. Sections (e) through (h) deal with related, but less important, issues of the control of substance abuse. Section 812 is perhaps of greatest interest to the general reader in that it establishes the system of classifying drugs still used in the United States, along with the criteria for classification and the original list of drugs to be included in each schedule (since greatly expanded):

There are established five schedules of controlled substances, to be known as schedules I, II, III, IV, and V. Such schedules shall initially consist of the substances listed in this section. The schedules established by this section shall be updated and republished on a semiannual basis during the two-year period beginning one year after October 27, 1970, and shall be updated and republished on an annual basis thereafter.

Except where control is required by United States obligations under an international treaty, convention, or protocol, in effect on October 27, 1970, and except in the case of an immediate precursor, a drug or other substance may not be placed in any schedule unless the findings required for such schedule are made with respect to such drug or other substance. The findings required for each of the schedules are as follows:

Schedules I, II, III, IV, and V shall, unless and until amended [1] pursuant to section 811 of this title, consist of the following drugs or other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated: The initial list of drugs under each schedule follows.

Source: U.S. Code, Title 21, Chapter 13.

The U.S. Supreme Court has acted on a number of cases involving drug testing in a variety of situations. Its first decision in a school-related setting came in 1995 in the case of Vernonia School District 47J, Petitioner V. Wayne Acton, et ux. In that case, the school board of the Vernonia (Oregon) school district decided that any student wishing to participate in athletics at the school had to sign an agreement to take a drug test. One student who declined to do so, James Acton, chose not to take the test, and was prohibited from joining the school’s seventh-grade football team. Ultimately, his parents brought suit against the school district on his behalf, claiming that suspicionless drug testing was unconstitutional. The case worked its way through the courts, with each side recording at least one favorable ruling along the way, until it reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1995, at which time the Court ruled for the school district by a vote of 6 to 3. The main arguments of the Court, as provided in Justice Scalia’s decision, were as follows (citations omitted, as indicated by ellipsis, …).

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that the Federal Government shall not violate “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures … .“We have held that the Fourteenth Amendment extends this constitutional guarantee to searches and seizures by state officers, … including public school officials. … In Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Assn., … we held that state compelled collection and testing of urine, such as that required by the Student Athlete Drug Policy, constitutes a “search” subject to the demands of the Fourth Amendment. …

As the text of the Fourth Amendment indicates, the ultimate measure of the constitutionality of a governmental search is “reasonableness.” At least in a case such as this, where there was no clear practice, either approving or disapproving the type of search at issue, at the time the constitutional provision was enacted, … whether a particular search meets the reasonableness standard” ‘is judged by balancing its intrusion on the individual’s Fourth Amendment interests against its promotion of legitimate governmental interests.’ “… Where a search is undertaken by law enforcement officials to discover evidence of criminal wrongdoing, this Court has said that reasonableness generally requires the obtaining of a judicial warrant. … Warrants cannot be issued, of course, without the showing of probable cause required by the Warrant Clause. But a warrant is not required to establish the reasonableness of all government searches; and when a warrant is not required (and the Warrant Clause therefore not applicable), probable cause is not invariably required either. A search unsupported by probable cause can be constitutional, we have said, “when special needs, beyond the normal need for law enforcement, make the warrant and probable cause requirement impracticable.” …

We have found such “special needs” to exist in the public school context. There, the warrant requirement “would unduly interfere with the maintenance of the swift and informal disciplinary procedures [that are] needed,” and “strict adherence to the requirement that searches be based upon probable cause” would undercut “the substantial need of teachers and administrators for freedom to maintain order in the schools.” … The school search we approved in T. L. O., while not based on probable cause, was based on individualized suspicion of wrongdoing. As we explicitly acknowledged, however, “ ‘the Fourth Amendment imposes no irreducible requirement of such suspicion,’ ” … We have upheld suspicionless searches and seizures to conduct drug testing of railroad personnel involved in train accidents, … ; to conduct random drug testing of federal customs officers who carry arms or are involved in drug interdiction. …

…

Fourth Amendment rights, no less than First and Fourteenth Amendment rights, are different in public schools than elsewhere; the “reasonableness” inquiry cannot disregard the schools’ custodial and tutelary responsibility for children. For their own good and that of their classmates, public school children are routinely required to submit to various physical examinations, and to be vaccinated against various diseases. . .

Legitimate privacy expectations are even less with regard to student athletes. School sports are not for the bashful. They require “suiting up” before each practice or event, and showering and changing afterwards. …

There is an additional respect in which school athletes have a reduced expectation of privacy. By choosing to “go out for the team,” they voluntarily subject themselves to a degree of regulation even higher than that imposed on students generally. In Vernonia’s public schools, they must submit to a preseason physical exam (James testified that his included the giving of a urine sample, App. 17), they must acquire adequate insurance coverage or sign an insurance waiver, maintain a minimum grade point average, and comply with any “rules of conduct, dress, training hours and related matters as may be established for each sport by the head coach and athletic director with the principal’s approval.” … Somewhat like adults who choose to participate in a “closely regulated industry,” students who voluntarily participate in school athletics have reason to expect intrusions upon normal rights and privileges, including privacy.

Having considered the scope of the legitimate expectation of privacy at issue here, we turn next to the character of the intrusion that is complained of. We recognized in Skinner that collecting the samples for urinalysis intrudes upon “an excretory function traditionally shielded by great privacy.” … We noted, however, that the degree of intrusion depends upon the manner in which production of the urine sample is monitored. … Under the District’s Policy, male students produce samples at a urinal along a wall. They remain fully clothed and are only observed from behind, if at all. Female students produce samples in an enclosed stall, with a female monitor standing outside listening only for sounds of tampering. These conditions are nearly identical to those typically encountered in public restrooms, which men, women, and especially school children use daily. Under such conditions, the privacy interests compromised by the process of obtaining the urine sample are in our view negligible.

Finally, we turn to consider the nature and immediacy of the governmental concern at issue here, and the efficacy of this means for meeting it. In both Skinner and Von Raab, we characterized the government interest motivating the search as “compelling.” …

That the nature of the concern is important-indeed, perhaps compelling can hardly be doubted. Deterring drug use by our Nation’s schoolchildren is at least as important as enhancing efficient enforcement of the Nation’s laws against the importation of drugs, which was the governmental concern in Von Raab, …, or deterring drug use by engineers and trainmen, which was the governmental concern in Skinner. …

Taking into account all the factors we have considered above-the decreased expectation of privacy, the relative unobtrusiveness of the search, and the severity of the need met by the search we conclude Vernonia’s Policy is reasonable and hence constitutional.

Source: Vernonia School District 47J, Petitioner v. Wayne Acton, et ux., etc. 515 U.S. 646 (1995).

One of the most contentious issues related to the use of illegal drugs concerns the use of marijuana to treat a wide variety of medical conditions, such as alcohol abuse, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or AD/HD), various forms of arthritis, asthma, atherosclerosis, autism, bipolar disorder, colorectal cancer, depression, epilepsy, digestive diseases, hepatitis C, hypertension, leukemia, and skin tumors, to name just a few. The drug has also been recommended for the treatment of side effects of various diseases and of treatments used against those diseases, side effects such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and weight loss. While many medical professionals, laypersons, and government officials support the legalization of marijuana for use in such situations, many others argue that marijuana is still an illegal drug in the United States, and its use should be prohibited even for such “compassionate” situations as those listed here. Local, state, and federal courts have had to decide a number of cases with regard to the “compassionate use” versus “illegal drug” controversy over the past two decades. More and more of these cases have arisen as individual states have adopted laws that permit the use of marijuana in certain medical situations. As of early 2017, 25 states in the United States have adopted such laws. A decision in the most recent medical marijuana case by the U.S. Supreme Court was announced on June 6, 2005. In that case, the Court was asked to decide whether the federal government had the authority under the U.S. Constitution to prohibit the local cultivation and use of marijuana that was approved by the state of California. The Court decided in favor of the U.S. government in this case by a vote of 6 to 3. That decision did not end the controversy over the medical use of marijuana, however, as four years later the Court, in an unsigned statement, rejected appeals from San Bernardino and San Diego Counties in California to have the California state medical marijuana law overturned because it violated federal restrictions on the use of the drug for any purpose whatsoever. The main points in the Gonzales v. Raich case are cited here (citations omitted, as indicated by ellipsis).

In the introduction to his ruling for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens lays out the fundamental constitutional issue and the basis for the Court’s decision:

The case is made difficult by respondents’ strong arguments that they will suffer irreparable harm because, despite a congressional finding to the contrary, marijuana does have valid therapeutic purposes. The question before us, however, is not whether it is wise to enforce the statute in these circumstances; rather, it is whether Congress’ power to regulate interstate markets for medicinal substances encompasses the portions of those markets that are supplied with drugs produced and consumed locally. Well-settled law controls our answer. The CSA [Controlled Substances Act] is a valid exercise of federal power, even as applied to the troubling facts of this case. We accordingly vacate the judgment of the Court of Appeals.

Later in his statement, Justice Stevens highlights two essential points about the case:

First, the fact that marijuana is used “for personal medical purposes on the advice of a physician” cannot itself serve as a distinguishing factor… . The CSA designates marijuana as contraband for any purpose; in fact, by characterizing marijuana as a Schedule I drug, Congress expressly found that the drug has no acceptable medical uses. Moreover, the CSA is a comprehensive regulatory regime specifically designed to regulate which controlled substances can be utilized for medicinal purposes, and in what manner. Indeed, most of the substances classified in the CSA “have a useful and legitimate medical purpose.” … Thus, even if respondents are correct that marijuana does have accepted medical uses and thus should be redesignated as a lesser schedule drug, the CSA would still impose controls beyond what is required by California law. The CSA requires manufacturers, physicians, pharmacies, and other handlers of controlled substances to comply with statutory and regulatory provisions mandating registration with the DEA, compliance with specific production quotas, security controls to guard against diversion, recordkeeping and reporting obligations, and prescription requirements… . Furthermore, the dispensing of new drugs, even when doctors approve their use, must await federal approval… . Accordingly, the mere fact that marijuana—like virtually every other controlled substance regulated by the CSA—is used for medicinal purposes cannot possibly serve to distinguish it from the core activities regulated by the CSA.

…

Second, limiting the activity to marijuana possession and cultivation “in accordance with state law” cannot serve to place respondents’ activities beyond congressional reach. The Supremacy Clause unambiguously provides that if there is any conflict between federal and state law, federal law shall prevail. It is beyond peradventure that federal power over commerce is “ ‘superior to that of the States to provide for the welfare or necessities of their inhabitants,’ “however legitimate or dire those necessities may be… . Just as state acquiescence to federal regulation cannot expand the bounds of the Commerce Clause, … so too state action cannot circumscribe Congress’ plenary commerce power.

Justice Stevens concludes with a brief statement about one way in which those in favor of medical marijuana can achieve their objectives:

We do note, however, the presence of another avenue of relief. As the Solicitor General confirmed during oral argument, the statute authorizes procedures for the reclassification of Schedule I drugs. But perhaps even more important than these legal avenues is the democratic process, in which the voices of voters allied with these respondents may one day be heard in the halls of Congress.

Source: Gonzales v. Raich 545 U.S. 1 (2005).

The question as to whether the federal government should have any control over the use of tobacco has been an issue in the United States for many years. Since tobacco use is not prohibited by any federal law, some people have argued that the federal government has no authority, legal or moral, to control the use of tobacco products. Other observers disagree. They point out that tobacco products contain substances that are harmful to a person’s health and that some agency in the U.S. government—presumably the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—should have some authority to regulate the use of tobacco products. In 2009, that issue was resolved to some extent when the U.S. Congress passed legislation to give the FDA authority to regulate the use of tobacco products. The legislation was originally introduced in the House of Representatives by Rep. Henry Waxman (D–CA) on March 22, 2009, as H.R.1256, while matching legislation was introduced in the U.S. Senate by Sen. Edward Kennedy (D–MA) on May 5, 2009. In a somewhat surprising turn of events, the bills moved quickly through the Congress, were approved on June 12, 2009, and signed by President Barack Obama on June 22, 2009. The bill is 84 pages in length in the U.S. Code, but the fundamental rationale of the act is expressed in its first few sections, which are reprinted here.

The act consists of four main sections: Table of Contents, Authority of the Food and Drug Administration, Tobacco Product Warnings, Constituent and Smoke Constituent Disclosure, and Prevention of Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. The first part of the act outlines its rationale in its “Findings” section, which consists of 49 statements about tobacco, its health effects, its marketing, and other related issues. Among these findings are the following:

Source: Public Law 111–31, June 22, 2009.

One of the most significant changes in the use of substances for recreational purposes in recent history has been the development of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), devices for the delivery of tobacco-like products (especially nicotine) by means of a battery-operated vaporizer. Considerable dispute has developed over the safety and usefulness of e-cigarettes, producing, as expected, a number of court cases dealing with their manufacture, distribution, and use. One of the most important of those cases arose out of a decision by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to begin regulating e-cigarettes under the authority granted to it by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FDCA). Some e-cigarette makers argued that the appropriate regulatory power was not the FDCA, but the Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (TCA), which provided different standards for the tobacco products that the FDA could regulate. A district court agreed with the e-cigarette companies and, when the FDA appealed to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, that court agreed with the lower court’s decision. As a consequence, e-cigarettes are currently not regulated by any federal statute or regulation. The appeal court’s ruling was as follows. (Asterisks [*] represent omitted citations.)

Under the FDCA, the FDA has authority to regulate articles that are “drugs,” “devices,” or drug/device combinations. 21 U.S.C. § 321(g)(1) defines drugs to include (B) articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals; and (C) articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.

*

Until 1996, the FDA had never attempted to regulate tobacco products under the FDCA (with one exception, irrelevant for reasons discussed below) unless they were sold for therapeutic uses, that is, for use in the “diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease” under § 321(g)(1)(B). *But in that year, the FDA changed its long-held position, promulgating regulations affecting tobacco products as customarily marketed, i.e., ones sold without therapeutic claims. *The agency asserted that nicotine is a drug that affects the structure or function of the body under § 321(g)(1)(C) and that cigarettes and smokeless tobacco were therefore drug/device combinations falling under the FDA’s regulatory purview, even absent therapeutic claims.*

In FDA v. Brown & Williamson, the Supreme Court rejected the FDA’s claimed FDCA authority to regulate tobacco products as customarily marketed. Looking to the FDCA’s “overall regulatory scheme,” the “tobacco-specific legislation” enacted since the FDCA, and the FDA’s own frequently asserted position, it held that Congress had “ratified … the FDA’s plain and resolute position that the FDCA gives the agency no authority to regulate tobacco products as customarily marketed.”*

To fill the regulatory gap identified in To fill the regulatory gap identified in Brown & Williamson, Congress in 2009 passed the Tobacco Act, Pub. L. No. 111-31, 123 Stat. 1776, 21 U.S.C. §§ 387 et seq., providing the FDA with authority to regulate tobacco products. The act defines tobacco products so as to include all consumption products derived from tobacco except articles that qualify as drugs, devices, or drug-device combinations under the FDCA:

[The court then discusses in detail the history of tobacco legislation and its implications for this particular case. They conclude that:]

… Brown & Williamson interprets the six statutes [passed by Congress] not as a particular carve-out from the FDCA for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco (plus any additional products covered in the six statutes, which the FDA briefs make no effort to itemize), but rather as “a distinct regulatory scheme to address the problem of tobacco and health”—one that Congress intended would “preclude[] any role for the FDA” with respect to “tobacco absent claims of therapeutic benefit by the manufacturer.” *In doing so, Congress also “persistently acted to preclude a meaningful role for any administrative agency in making policy on the subject of tobacco and health.” *As customarily marketed, tobacco products were to remain the province of Congress.

[The court’s opinion then concludes with:]

As we have already noted, the FDA has authority to regulate customarily marketed tobacco products—including ecigarettes—under the Tobacco Act. It has authority to regulate therapeutically marketed tobacco products under the FDCA’s drug/device provisions. And, as this decision is limited to tobacco products, it does not affect the FDA’s ability to regulate other products under the “structure or any function” prong defining drugs and devices in 21 U.S.C.§ 321 (g) and (h), as to the scope of which—tobacco products aside—we express no opinion. Of course, in the event that Congress prefers that the FDA regulate e-cigarettes under the FDCA’s drug/device provisions, it can always so decree.

The judgment of the district court is

Affirmed.

Source: Sottera, Inc., Doing Business as Njoy, Appellee v. Food & Drug Administration, et al., Appellants (No. 10 5032; 627 F.3d 891) (2010).

The decision by many states to approve the use of marijuana for medical purposes has created a problem for the federal government. Since marijuana is still a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, should or must federal law enforcement agencies follow federal law or state law in dealing with individuals who use the drug in states where it has been approved for medical use? The administration of President Barack Obama made up its mind on this issue early on in his term of office, deciding essentially not to prosecute people who were using marijuana for medical purposes in states that had adopted laws permitting such use. Perhaps the most famous statement on the issue was announced to U.S. attorneys in a memorandum from Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole in August 2013, a portion of which is reprinted here.

As the Department noted in its previous guidance, Congress has determined that marijuana is a dangerous drug and that the illegal distribution and sale of marijuana is a serious crime that provides a significant source of revenue to large-scale criminal enterprises, gangs, and cartels. The Department of Justice is committed to enforcement of the CSA consistent with those determinations. The Department is also committed to using its limited investigative and prosecutorial resources to address the most significant threats in the most effective, consistent, and rational way. In furtherance of those objectives, as several states enacted laws relating to the use of marijuana for medical purposes, the Department in recent years has focused its efforts on certain enforcement priorities that are particularly important to the federal government:

These priorities will continue to guide the Department’s enforcement of the CSA against marijuana-related conduct. Thus, this memorandum serves as guidance to Department attorneys and law enforcement to focus their enforcement resources and efforts, including prosecution, on persons or organizations whose conduct interferes with any one or more of these priorities, regardless of state law. [Footnote omitted here.]

Outside of these enforcement priorities, the federal government has traditionally relied on states and local law enforcement agencies to address marijuana activity through enforcement of their own narcotics laws. For example, the Department of Justice has not historically devoted resources to prosecuting individuals whose conduct is limited to possession of small amounts of marijuana for personal use on private property. Instead, the Department has left such lowerlevel or localized activity to state and local authorities and has stepped in to enforce the CSA only when the use, possession, cultivation, or distribution of marijuana has threatened to cause one of the harms identified above.

The enactment of state laws that endeavor to authorize marijuana production, distribution, and possession by establishing a regulatory scheme for these purposes affects this traditional joint federal-state approach to narcotics enforcement. The Department’s guidance in this memorandum rests on its expectation that states and local governments that have enacted laws authorizing marijuana-related conduct will implement strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems that will address the threat those state laws could pose to public safety, public health, and other law enforcement interests. A system adequate to that task must not only contain robust controls and procedures on paper; it must also be effective in practice. Jurisdictions that have implemented systems that provide for regulation of marijuana activity must provide the necessary resources and demonstrate the willingness to enforce their laws and regulations in a manner that ensures they do not undermine federal enforcement priorities.

Source: Memorandum for All United States Attorneys. 2013. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/3052013829132756857467.pdf. Accessed on May 7, 2016.

Brandon Coats was a customer service representative for Dish Network. Coats is a quadriplegic who has been in a wheelchair since he was a teenager. He obtained a license in Colorado in 2009 for the use of marijuana for medical purposes. In 2010, Coats failed a test for THC conducted by Dish, the result of his having used marijuana during his off hours. He sued the company on the basis of Colorado law that prohibits a company from firing a person for carrying on legal activities while not on the job. Coats noted that medical marijuana was legal in Colorado at the time of his firing, so the company’s action violated state law. The district court, appeals court, and supreme court all disagreed with Coats, as the following decision indicates. Ellipses indicate omitted text.

We review de novo the question of whether medical marijuana use prohibited by federal law is a “lawful activity” protected under section 24-34-402.5 [the relevant state law on which Coats bases his claim]… .

We still must determine, however, whether medical marijuana use that is licensed by the State of Colorado but prohibited under federal law is “lawful” for purposes of section 24-34-402.5. Coats contends that the General Assembly intended the term “lawful” here to mean “lawful under Colorado state law,” which, he asserts, recognizes medical marijuana use as “lawful.” … We do not read the term “lawful” to be so restrictive. Nothing in the language of the statute limits the term “lawful” to state law. Instead, the term is used in its general, unrestricted sense, indicating that a “lawful” activity is that which complies with applicable “law,” including state and federal law. We therefore decline Coats’s invitation to engraft a state law limitation onto the statutory language… .

Echoing [appeals court] Judge Webb’s dissent, Coats argues that because the General Assembly intended section 24-34-402.5 to broadly protect employees from discharge for outside-of-work activities, we must construe the term “lawful” to mean “lawful under Colorado law.” … In this case, however, we find nothing to indicate that the General Assembly intended to extend section 24-34-402.5’s protection for “lawful” activities to activities that are unlawful under federal law. In sum, because Coats’s marijuana use was unlawful under federal law, it does not fall within section 24-34-402.5’s protection for “lawful” activities.

Source: Coats v. Dish Network. Colorado Supreme Court. Case No. 13SC394.

The Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment adopted by the U.S. Congress in 2015 appeared to be fairly straightforward: It forbade the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from pursuing individuals for the use of medical marijuana in states where the practice was legal. The DEA, however, had a different view of the amendment; It believed that the agency was prohibited from acting only against states in which medical marijuana was legal, not against individuals in those states. The question as to which interpretation was correct was first resolved later in 2015 when a case arose between a medical marijuana group in Marin County, California, and the DEA. The court concluded that “the Government’s contrary reading so tortures the plain meaning of the statute” that it had to be rejected virtually out of hand. Specifically, it explained that:

The plain reading of the text of Section 538 forbids the Department of Justice from enforcing this injunction against MAMM to the extent that MAMM operates in compliance with California law.

…

… this Court is not in a position to “override Congress’ policy choice, articulated in a statute, as to what behavior should be prohibited.” … On the contrary: This Court’s only task is to interpret and apply Congress’s policy choices, as articulated in its legislation. And in this instance, Congress dictated in Section 538 that it intended to prohibit the Department of Justice from expending any funds in connection with the enforcement of any law that interferes with California’s ability to “implement [its] own State law[] that authorize[s] the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana.”

…

[The court then noted that the sponsors of the amendment had addressed this very issue in offering it to the House:]

In fact, the members of Congress who drafted Section 538 had the opportunity to respond to the very same argument that the DOJ advances here. In a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder on April 8, 2015, Congressmen Dana Rohrabacher and Sam Farr responded as follows to “recent statements indicating that the [DOJ] does not believe a spending restriction designed to protect [the medical marijuana laws of 35 states] applies to specific ongoing cases against individuals and businesses engaged in medical marijuana activity”:

As the authors of the provision in question, we write to inform you that this interpretation of our amendment is emphatically wrong. Rest assured, the purpose of our amendment was to prevent the Department from wasting its limited law enforcement resources on prosecutions and asset forfeiture actions against medical marijuana patients and providers, including businesses that operate legally under state law. In fact, a close look at the Congressional Record of the floor debate of the amendment clearly illustrates the intent of those who sponsored and supported this measure. Even those who argued against the amendment agreed with the proponents’ interpretation of their amendment.

For the foregoing reasons, as long as Congress precludes the Department of Justice from expending funds in the manner proscribed by Section 538, the permanent injunction will only be enforced against MAMM insofar as that organization is in violation of California “State laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana.”

Source: United States of America, Plaintiff, v. Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana, and Lynette Shaw. United States District Court for the Northern District of California. https://cases.justia.com/federal/district-courts/california/candce/3:1998cv00086/116898/277/0.pdf?ts=1445324671. Accessed on July 4, 2016.

One of the most serious substance abuse problems of the early twenty-first century is prescription drug abuse, in which individuals obtain, in one way or another, prescriptions drugs (such as opioids) that can then be used for recreational or other nonmedical purposes. A common method by which such drugs are obtained is by going from physician to physician (a procedure known as “doctor shopping”) having the same prescription refilled over and over again. Although the federal government has no specific law prohibiting such practices, every state has enacted some form of legislation to prevent doctor shopping. These laws differ substantially from state to state. The two selections provided here are examples of the types of laws that exist.

22-42-17. Controlled substances obtained concurrently from different medical practitioners—Misdemeanor. Any person who knowingly obtains a controlled substance from a medical practitioner and who knowingly withholds information from that medical practitioner that he has obtained a controlled substance of similar therapeutic use in a concurrent time period from another medical practitioner is guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor.

Source: SL 1990, ch 168. http://legis.sd.gov/Statutes/Codified_Laws/DisplayStatute.aspx?Type=Statute&Statute=22-42-17. Accessed on July 4, 2016.

Sec. 21a-266. (Formerly Sec. 19-472). Prohibited acts. (a) No person shall obtain or attempt to obtain a controlled substance or procure or attempt to procure the administration of a controlled substance (1) by fraud, deceit, misrepresentation or subterfuge, or (2) by the forgery or alteration of a prescription or of any written order, or (3) by the concealment of a material fact, or (4) by the use of a false name or the giving of a false address.

Source: Chapter 420b. Dependency-Producing Drugs. https://www.cga.ct.gov/current/pub/chap_420b.htm#sec_21a-266. Accessed on July 4, 2016.

In July 2016, the U.S. Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, a piece of legislation called by some observers “the most consequential piece of drug legislation adopted in the United States in forty years.” The bill was 130 pages long and covered a vast array of issues relating to opioid use and misuse. The rage of topics can be appreciated from the Table of Contents at the beginning of the bill, which reads as follows:

Sec. 101. Task force on pain management.

Sec. 102. Awareness campaigns.

Sec. 103. Community-based coalition enhancement grants to address local drug crises.

Sec. 104. Information materials and resources to prevent addiction related to youth sports injuries.

Sec. 105. Assisting veterans with military emergency medical training to meet requirement for becoming civilian health care professionals.

Sec. 106. FDA opioid action plan.

Sec. 107. Improving access to overdose treatment.

Sec. 108. NIH opioid research.

Sec. 109. National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting Reauthorization.

Sec. 110. Opioid overdose reversal medication access and education grant programs.

Sec. 201. Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Grant Program.

Sec. 202. First responder training.

Sec. 203. Prescription drug take back expansion.

Sec. 301. Evidence-based prescription opioid and heroin treatment and interventions demonstration.

Sec. 302. Building communities of recovery.

Sec. 303. Medication-assisted treatment for recovery from addiction.

Sec. 401. GAO report on recovery and collateral consequences.

Sec. 501. Improving treatment for pregnant and postpartum women.

Sec. 502. Veterans treatment courts.

Sec. 503. Infant plan of safe care.

Sec. 504. GAO report on neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

Sec. 601. State demonstration grants for comprehensive opioid abuse response.

Sec. 701. Grant accountability and evaluations.

Sec. 702. Partial fills of schedule II controlled substances.

Sec. 703. Good samaritan assessment.

Sec. 704. Programs to prevent prescription drug abuse under Medicare parts C and D.

Sec. 705. Excluding abuse-deterrent formulations of prescription drugs from the Medicaid additional rebate requirement for new formulations of prescription drugs.

Sec. 706. Limiting disclosure of predictive modeling and other analytics technologies to identify and prevent waste, fraud, and abuse.

Sec. 707. Medicaid Improvement Fund.

Sec. 708. Sense of the Congress regarding treatment of substance abuse epidemics.

Sec. 801. Protection of classified information in Federal court challenges relating to designations under the Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act.

Sec. 901. Short title.

Sec. 902. Definitions.

Sec. 911. Improvement of opioid safety measures by Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 912. Strengthening of joint working group on pain management of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense.

Sec. 913. Review, investigation, and report on use of opioids in treatment by Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 914. Mandatory disclosure of certain veteran information to State controlled substance monitoring programs.

Sec. 915. Elimination of copayment requirement for veterans receiving opioid antagonists or education on use of opioid antagonists.

Sec. 921. Community meetings on improving care furnished by Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 922. Improvement of awareness of patient advocacy program and patient bill of rights of Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 923. Comptroller General report on patient advocacy program of Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 924. Establishment of Office of Patient Advocacy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 931. Expansion of research and education on and delivery of complementary and integrative health to veterans.

Sec. 932. Expansion of research and education on and delivery of complementary and integrative health to veterans.

Sec. 933. Pilot program on integration of complementary and integrative health and related issues for veterans and family members of veterans.

Sec. 941. Additional requirements for hiring of health care providers by Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sec. 942. Provision of information on health care providers of Department of Veterans Affairs to State medical boards.

Sec. 943. Report on compliance by Department of Veterans Affairs with reviews of health care providers leaving the Department or transferring to other facilities.

Source: S.524—Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016. Congress.Gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524/text. Accessed on December 26, 2016.

Gailen Lopton, seated, talks with Seattle police officer Tom Christenson in downtown Seattle on April 7, 2015. When Lopton was caught injecting heroin in a downtown alley in March, police officers offered him a chance to enroll in a first-of-its-kind program called Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, aimed at keeping low-level drug offenders and prostitutes out of jail and providing services for housing, counseling, and job training. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)