CHAPTER 2

The Lead Age: Heavy Metals, Low IQs

If you were going to put something in a population to keep them down for generations to come, it would be lead.

—DETROIT PEDIATRICIAN MONA HANNA-ATTISHA1

Anthony Miller, ten, could not sit still.* Ensconced in the steely mesh of an Aeron chair at the head of a conference table ringed with lawyers, his eyes darted about the room.

Anthony glanced quickly at the camera recording him, then looked down nervously, then up again, at his mother and her lawyer. Shifting in his seat, he worried that he would somehow give the wrong answers at what seemed like an important meeting, although everyone had assured him he need only do one thing: tell the truth.

After a few moments, the lawyer asked, “If your mother were to win the case and you had plenty of money, what would you want most?” Abruptly, Anthony sat up straight, looking intently at the lawyer.

“I want to read,” he said with audible fervor. “I just want to be able to read.”

Anthony is one of at least 37,500 Baltimore children who suffered lead poisoning between 2003 and 2015. Nearly all were African American.

Lead poisoning is often caused by exposure to industrial emissions, tainted water, or poorly maintained pre-1978 housing that features flaking lead paint and lead dust. Nearly two of every five African American homes are plagued by lead-based paint.

Trojan Horse: Lead Pervades Baltimore

One of these children was Ericka Grimes.

The young woman fitted the key of their new apartment into the gleaming brass lock and turned it smoothly, with a satisfying click. She smiled up at her husband: already better than their old house, where the key often got stuck or jammed in the lock, slowing her down when she had an armful of groceries. It’s true that the house itself was weathered and a bit shabby, but the young mother cared most about what it didn’t have: lead, a toxic metal common in Baltimore’s African American neighborhoods.

She knew that children sickened and died as a result of growing up in lead-tainted housing, and she was determined to avoid that fate for her children. She was therefore encouraged when, three years after moving in, she was approached by the Kennedy Krieger Institute (KKI) to participate in a lead-abatement study at her property. On its website KKI described itself as a place where she could access an “interdisciplinary team of experts in the problems and injuries that affect your child’s brain, and receive personal compassionate care for your child.” Moreover, it is affiliated with the prestigious Johns Hopkins University.

When the KKI drew her daughter Ericka’s blood on April 9, 1993, her reading was a reassuring nine micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (µg/dL), which at the time was a “normal” reading according to CDC guidelines. (These were later revised. Experts now consider no level of blood lead safe.)

When Ericka was retested the following September 15, her blood-lead reading had shot up to 32 µg/dL, a “highly elevated” reading that is six times higher than the allowable limit set by the CDC.

Two-year-old Ericka had fallen victim to the mid-1990s “Repair and Maintenance Study” in which KKI researchers undertook a study of African American families who lived in 108 units of decrepit housing with interiors that were encrusted with crumbling, peeling lead paint.

Lead paint is a notorious cause of acute illness and chronic mental retardation in young children. Among its many signs and symptoms are slowed growth, anemia, heart disorders, reproductive problems, reduced kidney function, lowered IQ, and learning and behavioral difficulties. Unfortunately, these take time to show themselves, and it is virtually impossible to tell that an infant like Ericka has suffered lead poisoning by looking at her: a medical evaluation, including a blood test, is needed.

Like many toddlers, Ericka had been poisoned when she inhaled airborne lead dust and ingested lead dust by putting her hands in her mouth after crawling on the floor. Perhaps she nibbled the peeling paint chips from windows and doorjambs, drawn by the sweet taste of the lead.

That same sweet taste led Romans to infuse their gastronomic delicacies and wine with lead, courting the mental devastation that some historians believe hastened the civilization’s decline. The lead used in everything from their cosmetics to the pipes in the empire’s famous aqueduct system did not help matters. Even the word for such systems, “plumbing,” derives from the Latin word for lead, plumbum, as does the chemical symbol for the metal, Pb.

For us, as for our forebears, lead’s sweet utility has proved disastrous, and we are suffering the same stultifying fate, although today it is not jaded Roman epicures but poor African American children in crumbling inner-city housing who suffer most from lead.

Why? It’s not as if we don’t know lead’s horrors. We now understand that we can protect children only by banning the use of lead paint and by offering lead-abatement programs that completely remove the remnants of the toxic paint and dust. As early as 1987 the CDC advocated complete abatement because there is no safe level of exposure.2

Yet the city of Baltimore abounds with lead-tainted low-income housing populated almost exclusively by African Americans. In Baltimore, statutes requiring that lead paint be thoroughly abated from home interiors have made renting lead-tainted housing illegal.

But Baltimore slumlords find removing this lead too expensive and some simply abandon the toxic houses. Cost concerns drove the agenda of the KKI researchers, who did not help parents completely remove children from sources of lead exposure. Instead, they allowed unwitting children to be exposed to lead in tainted homes, thus using the bodies of the children to evaluate cheaper, partial lead-abatement techniques of unknown efficacy in the old houses with peeling paint. Although they knew that only full abatement would protect these children, scientists decided to explore cheaper ways of reducing the lead threat.

So the KKI encouraged landlords of about 125 lead-tainted housing units to rent to families with young children. It offered to facilitate the landlords’ financing for partial lead abatement—only if the landlords rented to families with young children. Available records show that the exposed children were all black.

KKI researchers monitored changes in the children’s health and blood-lead levels, noting the brain and developmental damage that resulted from different kinds of lead-abatement programs.

These changes in the children’ bodies told the researchers how efficiently the different, economically stratified abatement levels worked. The results were compared to houses that either had been completely lead-abated or that were new and presumed not to harbor lead.

Scientists offered parents of children in these lead-laden homes incentives such as fifteen-dollar payments to cooperate with the study, but did not warn parents that the research potentially placed their children at risk of lead exposure.

Instead, literature given to the parents promised that researchers would inform them of any hazards.3 But they did not. And parents were not warned that their children were in danger, even after testing showed rising lead content in their blood.

This shocking research violated a number of ethical rules. To protect the safety and rights of research subjects, every federally funded human experiment must be approved by an institutional review board, or IRB, which is the institution’s principal body charged with protecting the subjects of medical research.4 One might wonder how the study cleared this hurdle, given the plan to maintain children’s exposure to a known toxic metal for research that was driven by economic issues and was nontherapeutic, providing no possible benefit to them. The IRB of the prestigious Johns Hopkins University, with which the KKI is affiliated, approved the protocols after helping the researchers refine their application in line with governmental requirements. Although the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) within the Department of Health and Human Services ostensibly provides governmental oversight of IRBs,5 routine scrutiny is nearly nonexistent. Many modern human studies have been approved and conducted although they are ethically flawed, sometimes deeply so.6

Ericka was exposed from her birth in 1992 until 1994, when her parents discovered that she was profoundly lead poisoned, and the family moved out. Their subsequent lawsuit against KKI alleged that the researchers were aware of the lead-paint hazard and that the KKI violated its duty to the children by not fully explaining the dangers of lead paint in the consent form that the families signed in order to participate in the study.

The parents of children in a similar study were given a consent form in which the KKI did not clearly disclose that the children might accumulate dangerous levels of lead in their blood as a result of the experiment, nor did it describe the effects of elevated blood lead, including damage to the central nervous system, irreversible behavioral problems, and death. Grimes’s parents also claim that the KKI “failed to warn in a timely manner or otherwise act to prevent the children’s exposure to the known presence of lead.”7

The KKI countered that its researchers had no contract or “special relationship” with the study subjects and owed no duty to them. The circuit court agreed. Ericka Grimes had lost.

But on August 16, 2001, Maryland’s top appellate court reversed this decision and ruled against the researchers. In doing so, it drew a parallel between the Grimes case and the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, a forty-year study in which hundreds of African American men in Alabama were lied to and maintained in an infected, ill condition by U.S. Public Health Service researchers who failed to treat their syphilis. The USPHS did this in order to study the disease’s ravages on the men’s bodies at autopsy, just as the bodies of the lead-exposed children were used to gather data.8

The appellate court found using the children as biologic monitors ethically indefensible, as the language in Judge R. Cathell’s opinion made clear. He wrote, “It can be argued that the researchers intended that the children be the canaries in the mines.”

Worse, as his decision noted, the children had been abandoned by the IRB that was charged with protecting them as research subjects: “The IRB was willing to aid researchers in getting around federal regulations designed to protect children used as subjects in nontherapeutic research. An IRB’s primary role is to assure the safety of human research subjects—not help researchers avoid safety or health-related requirements.”9

Ericka’s family eventually reached a settlement of its claims against KKI, but twenty-five other parents in the study filed a class-action suit against the Kennedy Krieger Institute in September 2011, accusing it of negligence, fraud, and battery as well as violations of Maryland’s consumer protection act. At the time of writing, no decision has been made on the case.

Although I am not involved in the class action, over the past decade I have worked as a consultant to law firms that represent children who, like Ericka, were sickened by lead in the Baltimore studies. Many researchers have defended such studies, and one of the stranger defenses I have heard, albeit only from one lawyer, is that because virtually all the children living in Baltimore’s lead-imbued housing were African American, maintaining them in toxic housing during the study was not something for which researchers should be blamed. This defense is not only patently ridiculous but also ignores the fact that some of the children poisoned in the experiment had not previously suffered dangerously elevated lead levels.

Such a claim of blamelessness is belied by the fact that the researchers were not objective, innocent bystanders. They actively encouraged landlords to rent to families with vulnerable young children by offering financial incentives.

The participation of a medical researcher, who is ethically and legally responsible for protecting human subjects, changes the scenario from a tragedy to an abusive situation. Moreover, this exposure was undertaken to enrich landlords and benefit researchers at the detriment of children, so it also evokes the shade of British philosopher Jeremy Bentham who wrote, “No man ought to take advantage of his own wrong.”10

Heavy-Metal Mayhem

How did lead become such an important hazard, and how did it come to preferentially threaten the minds of African Americans and other communities of color?

As early as the 1880s, scientists realized that lead plumbing was poisoning our water, like that of the Romans before us. By the 1920s many cities and towns passed statutes that banned or sharply restricted the use of lead pipes, but the lead industry, notably the Lead Industries Association (LIA), pushed back. The LIA’s vigorous “educational” campaign sought to rehabilitate lead’s image, muddying the waters by extolling the supposed virtues of lead over other building materials. It published flooding guides and dispatched expert lecturers to tutor architects, water authorities, plumbers, and federal officials in the science of how to repair and “safely” install lead pipes. All the while LIA staff published books and papers and gave lectures to architects and water authorities that downplayed lead’s dangers.11

Over the succeeding decades, the hazard was gradually forgotten, an early exercise in industry’s skill in manufacturing doubt regarding environmental poisoning. It would not be the last such success, and as a result, the contribution of lead pipes to the nation’s lead poisoning crisis continues in Flint, Michigan, and beyond. Meanwhile, lead-tainted water gradually took a backseat to what would prove its most efficient route of childhood poisoning—leaded gasoline.12

In the 1920s, when General Motors (GM) considered adding its patented chemical tetraethyl lead (TEL) to gasoline, it already had a cheap, ubiquitous, perfectly serviceable anti-knock13 compound for high-compression engines: ethanol, the same alcohol found in the beer, wine, and hard liquor that we drink.

Some beneficial effects of using ethanol fuel were recently illustrated when the airborne-lead concentration of São Paulo, Brazil, plummeted 65 percent between 1980 and 1985—and so did its notoriously high crime rate. In a bid to reduce its dependence on imported oil, Kevin Drum explained in Mother Jones, Brazil began substituting lead-free E95 fuel ethanol for vehicles in 1979. By 1987, the ethanol fueled nearly half the vehicles in Brazil and a much higher percentage in São Paulo, where the annual homicide rate fell from over 12,000 in 2000 to less than 5,000 in 2012. (Crime rates, Drum notes, typically plummet about twenty years after the drop in lead exposure, when the data of a new, unpoisoned generation are tallied.)14

But despite its safety, alcohol’s very cheapness and ubiquity worked against it in GM’s eyes. Alcohol was in common use and people even brewed it in home stills, so it was not “novel” and therefore could not be patented. This meant GM could not profit from its exclusive sale, nor could it hope to corner the automotive market. Moreover, Standard Oil declared itself “reluctant… to encourage the manufacture and sale of a competitive fuel [that is, ethanol] produced by an industry in no way related to petroleum.”15 Standard Oil’s dislike of the ethanol additive was a powerful disincentive for GM because it sought to partner with it and other energy behemoths like DuPont.16

So, in yet another example of industrial greed trumping public safety concerns, GM chose to use lead as an anti-knock additive in a 4:1 mix of gas to TEL, despite the fact that lead was costlier, less readily available, and, as GM knew from the beginning, “very poisonous.”

It was March 1922 when, as Kevin Drum writes, “Pierre du Pont wrote to his brother Irénée du Pont, Du Pont company chairman, that TEL is ‘a colorless liquid of sweetish odor, very poisonous if absorbed through the skin, resulting in lead poisoning almost immediately.’”17

Subsequently, gas emissions from cars and trucks drove up lead levels in the air alarmingly and permanently. Because inhalation is the most efficient route of poisoning, blood-lead levels rose around the country, especially quickly in children, who have proportionately more lung-surface area than adults.

Despite the 1922 caveat by DuPont, companies later denied—repeatedly—knowing that leaded gasoline was poisonous.

Lead may be the cause of the biggest childhood poisoning epidemic ever, because even today when we know the dangers of only minimal exposure, lead abounds in more than paint and gas. Lead lurks in battery cases, building materials, burial vault liners, lead crystal, pewter, solder, shielding, computer monitors, ceramic pots, television components, and even modern makeup. It is the most widely dispersed environmental poison affecting children in this country.

As with many environmental poisons, the affected communities are often characterized as “poor,” or of low socioeconomic status. But this language is imprecise, and it veils the heavily racial nature of exposures; this is an epidemic afflicting African American and Hispanic children as well as the poor.

About 39 percent of African Americans and 43 percent of Hispanics are poor, and some definitions of “socioeconomic” already subsume race as a factor. This means that race becomes an endemic but hidden characteristic of the affected neighborhoods. Also, middle-class blacks are far more likely than middle-class whites to suffer from environmental hazards placed in their communities. The 2014 report Who’s in Danger: A Demographic Analysis of Chemical Disaster Vulnerability Zones notes that middle-class African American households with incomes between $50,000 and $60,000 live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than those where very poor white households with incomes below $10,000 live.18

The failure to identify the imperiled groups as racial minorities may reflect a level of discomfort in acknowledging America’s racial disparities. These include the persistence of racial segregation and the slow violence of racial environmental poisoning. It may be instructive to remember that despite the fact that Flint is 57 percent black, the lead-poisoning crisis in the city was first described in 2014 as affecting a “poorer community” or a lower socioeconomic group. Only in 2016, the year the Center for Effective Government revealed that children of color constituted almost two-thirds of the 5.7 million children who live within a mile of a toxic facility, was the Flint lead crisis routinely described as a racial assault affecting African Americans.19

Descriptions of the vulnerable that focus on economics and exclude race are semantic shrouds that are not only euphemistic but inaccurate. Poverty is certainly a risk factor for environmental exposure, but race is a larger and more consistent one.

Industrial Secrets

This wasn’t always the case with lead poisoning. Lead was widely introduced into American homes for the same reasons the ancient Romans embraced it wholesale: it was useful, and it enhanced the home environment with higher-status ornaments and products.

Painted walls, for example, replaced wallpaper in midcentury homes because paint was more modern, easier to clean, and therefore more hygienic, as the industry reminded us. As TEL use in gas declined, the lead industry offset its losses by marketing lead pigments. It used powdery lead carbonate, which was mixed into oil-based paint to brighten colors and make the paint more durable and washable. Lead-based paint was used widely in schools, hospitals, and other public buildings.20

The lead industry knew that the paint, like TEL gas, was very poisonous.

As early as 1900, a Sherwin-Williams newsletter declared that lead was a “deadly cumulative poison.”21

In 1904, Sherwin-Williams’s own in-house magazine described lead as “poisonous in a large degree, both for workmen and for the inhabitants of a house.”

By 1912, the company National Lead reported to shareholders that women and children were forbidden from working on its lead products because of the devastating effects—all while the company continued to manufacture lead-based goods for home use, including children’s toys.

By 1955, the LIA health and safety director Manfred Bowditch wrote an internal memo, lamenting, “With us, childhood lead poisoning is common enough to constitute perhaps my major ‘headache.’”22

So the poisonous nature of lead paint was well known from the beginning. Safe, lead-free alternatives like ethanol and unleaded house paint were also available from the beginning. But the LIA’s aggressively deceptive marketing efforts in the early twentieth century made lead paint popular among homeowners and landlords.

Lead dust from the paint coated everything, including the lungs of children. When children become toddlers, able to move about and explore their poisoned world more freely, the real devastation began. Young children’s principal means of exploring the unfamiliar world is to put objects in their mouths. Even noxious tastes won’t discourage young children from mouthing objects, but lead’s sweetness encouraged them to lick and suck on painted cribs and windowsills, and to frequently put their unwashed hands in their mouths after peeling sweet paint chips off household surfaces.

This is a very efficient method of poisoning. A lead-paint chip no larger than a fingernail can send a toddler into a coma and death. One-tenth of that amount will lower his IQ.

The lead industry’s response? Rather than pull lead-based paint from the market in favor of safe alternatives, firms more aggressively touted lead paint as a healthy wall covering. Because it was so easy to wash, it was specifically recommended for children’s rooms. Lead pigment maker National Lead Industries, the same company that wouldn’t allow women and children workers in their lead paint factories due to safety concerns, ran a National Geographic ad in 1923 that claimed, “Lead helps to guard your health.” The following year, an advertisement by Sherwin-Williams boasted that after her home received a coat of lead paint, “Cousin Susie says her health improved instantly.”23

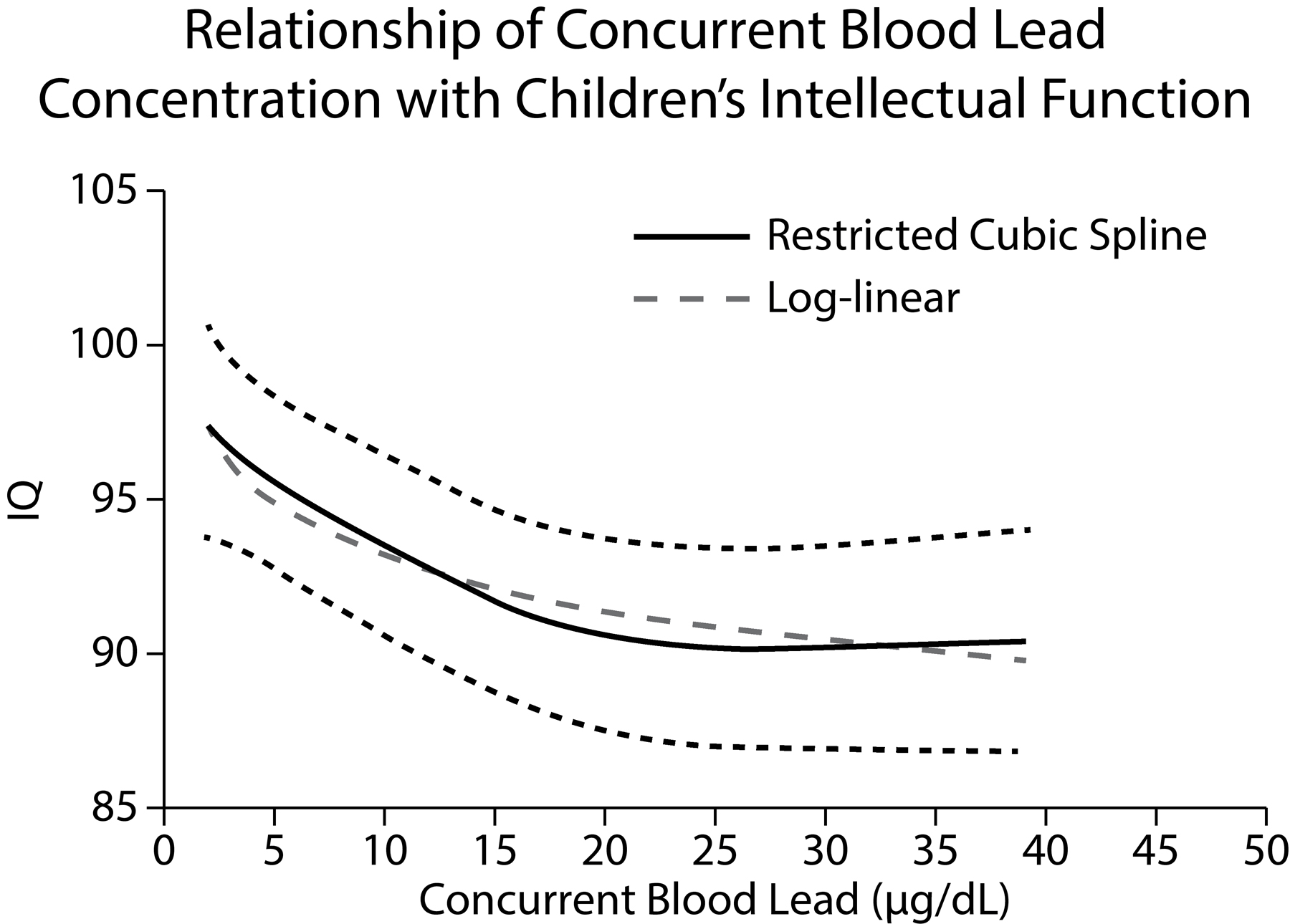

Lower IQs are found among children with the highest blood-lead concentrations.

In the 1990s, tobacco companies came under fire when Philip Morris sought to woo customers from an early age with trinkets like child-sized flip-flops that stamped the word “CAMEL” in the sand and cartoon characters like Joe Camel, which the Journal of the American Medical Association found was as recognizable to six-year-olds as Mickey Mouse. They were taking a page from the book of the lead industry, which marketed lead products designed specifically for children: lead-painted toy horses, train sets, and jewelry—even coloring books that celebrated the superior colors of leaded paint as vibrant hues that are perfect for the cheerful decor of children’s bedrooms.24

Of course, both chronic and acute exposures to lead poisoned industry workers, too. One of the more dramatic examples of this occurred on October 27, 1924, when eleven workers were poisoned by TEL gas at the Standard Oil research laboratory in Elizabeth, New Jersey. They suffered profound confusion, delirium, and “derangement” so dramatic that one had to be bound in a straitjacket before being hospitalized, where one worker died. Such mental symptoms were well known to the workers, who called the site the “loony gas building.”25 Similar outbreaks of poisoning, and madness among three hundred other workers who became psychotic and some of whom were also carried away in straitjackets, took place at the other two TEL manufacturing sites. Between three and fifteen workers died there, according to University of Pittsburgh professor Herbert L. Needleman, a preeminent lead-poisoning researcher.26 The Elizabeth, New Jersey, disaster spurred the beginning of restrictions on leaded gasoline, whose levels were progressively reduced by laws passed over the decades until 1974, when the Environmental Protection Agency required oil companies to stop putting lead in gasoline. In 1978, lead paint was banned in new home construction, although nothing barred its use in older and existing housing.

Eliminating lead from gas resulted in quantifiable and dramatic health gains. The amount of lead in Americans’ blood fell by four-fifths between 1975 and 1991.27 Fewer children fell into coma and death from lead inhalation, and as Kevin Drum of Mother Jones points out, the nation’s IQs even rose in the aftermath of lead’s banishment from gas.28

Public-health advocates campaigned to eradicate lead from paint, too, but the lead industry fought to retain its lucrative market with tactics similar to those that had allowed it to retain lead plumbing in the face of frank poisoning. The LIA successfully lobbied key lawmakers and public health officials, including scientists, to look the other way. Its viability was at stake, especially because some of its members, like the National Lead Company and Eagle-Picher (formerly Eagle White Lead), manufactured both lead paint and lead pipes.

Richard Rabin, M.D., recalls,

In 1933, the Massachusetts Department of Labor planned to prohibit the use of lead paint inside homes, due to the danger to young children. However, the Lead Industries Association, concerned that such a regulation could lead to the banning of lead paint in other states, persuaded the Labor Department to drop the rule. Instead, the Department issued a weak recommendation that lead paint not be used where children could have access to it, without reference to lead’s toxic nature.29

In 1956, LIA health and safety director Manfred Bowditch boasted to the Secretary of the Interior, who was responsible for regulating the lead industry, that “with the public health officials local, state, and national I been [sic] at some pains to cultivate their good will and get them into a receptive frame of mind as to our viewpoint. I feel this has paid off, as for example, in Chicago where we have been able to stave off a paint-labeling regulation like that here in New York.”30

As David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz reveal in their 2013 book Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America’s Children, the industry consistently denied that lead paint was a danger to children. Internal communications from the LIA imply that they seemed most worried about the economic effects of lead’s toxicity and about their public image.

In the first place it means thousands of items of unfavorable publicity every year. This is particularly true since most cases of lead poisoning today are in children, and anything sad that happens to a child is meat for newspaper editors and is gobbled up by the public.

It makes no difference that it is essentially a problem of slums, a public welfare problem. Just the same the publicity hits us where it hurts.31

Landlords who didn’t relish the prospect of expensive lead abatement and repainting also clung to such denials of responsibility.

The Uses of Doubt

The LIA and its scientists also churned doubt regarding lead’s dangers by minutely challenging data that demonstrated lead toxicity.

This pattern has been repeated consistently in the evaluation of environmental poisoning. Raising—and where necessary, creating—doubt in response to health data is a favored ploy of the industry and of the scientists it employs and funds. As public health researchers and practitioners amassed data showing sickness and death, the industry contested their studies and demanded ever-increasing levels of surety before any abatements or eradication commenced.

For the lead industry, as for the industries behind many subsequent poisoning cases, doubt became a useful foil against the expense of regulation. As the title of one book on the subject proclaims, Doubt Is Their Product.32

This corporate skepticism is often articulated as a scientific question, to wit, “Is there really incontrovertible evidence that lead in paint is a hazard demanding eradication?”

Demanding scientific proof sounds logical before undertaking an expensive ban and an even more expensive removal and rehabilitation of a toxic site. Some think that the expense and disruption demand certain proof. But finding such proof is very expensive, too: research requires a great deal of funding and other resources, and it can take decades to amass data that can utterly condemn or exonerate a suspect chemical.

But the most precious resource lost in the long decades of research required for absolute proof of a chemical’s harmfulness is health: the lives of the people who are sickened, killed, or hobbled by lowered intelligence during the long, expensive search for the ever-higher standards of proof demanded by industry and its scientists. “Its scientists” refers not only to those in its employ, but to those whose work it funds, because a wealth of studies show that industry-funded research, even that published in top-tier journals, tends to find results that buttress the interests of the industry that pays for them.33 Doubt was and is more than a scientific question: it is often a profitable stance as well.

Am I suggesting that chemicals suspected of causing illness be restricted or removed from the market even before we can prove that they cause the sickness, including memory loss, IQ loss, confusion, and behavioral problems suffered by those who are exposed to them? Yes.

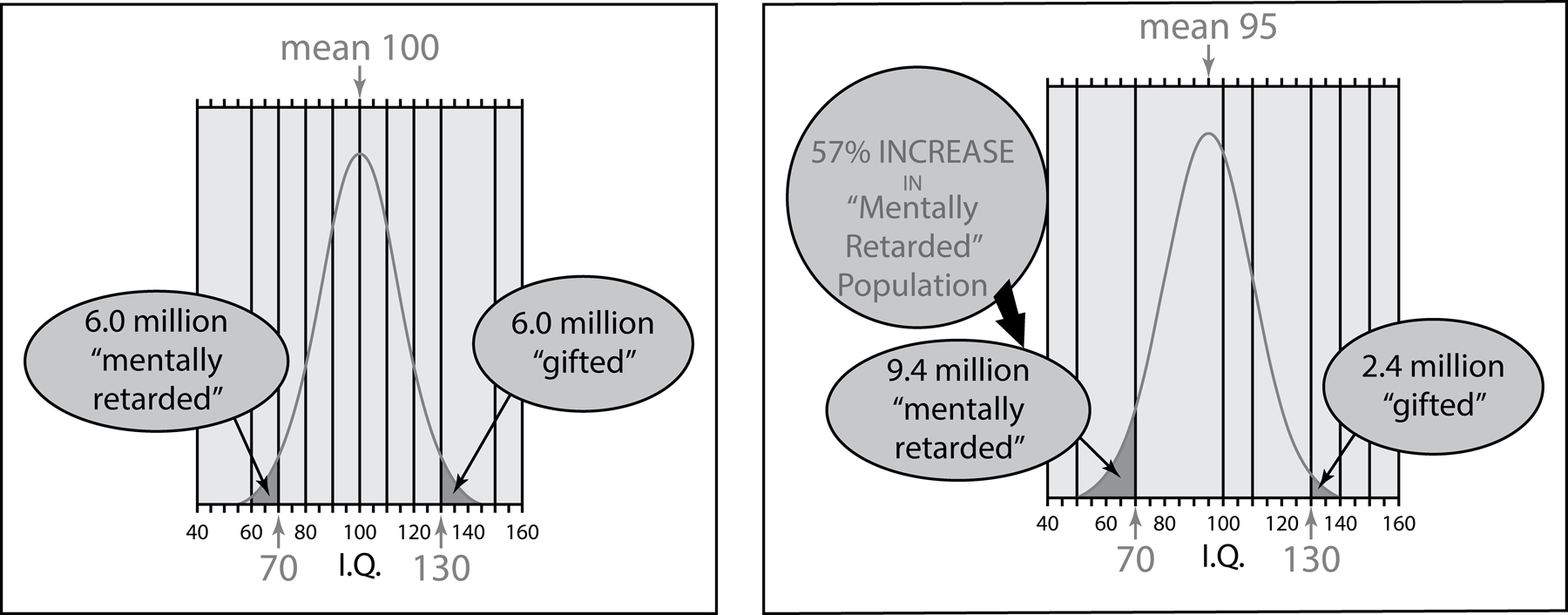

As early as 1988, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) estimated that the blood lead levels of 2.4 million U.S. children and 400,000 fetuses exceeded the blood-lead-level standards of the day, which were then quite high, at 15 µg/dL. This is a fraction of the millions who have fallen into comas, died, been permanently injured, or lost intellectual capacity as a result of lead poisoning while the industry successfully blocked regulation and bans by simultaneously hiding damning data and demanding incontrovertible proof that lead was injuring Americans. These life-changing illnesses and deaths cost victims and their families. But they also cost the nation a great deal of money for the victims’ medical care and their dependents’ care. And this widespread loss of intelligence costs the nation the brainpower it needs to compete in the modern industrialized economy. Even an average IQ loss of five points has been shown to shrink the pool of gifted U.S. children and to swell the ranks of the mentally incapacitated.

Unless we want to repeat this scenario with pesticides, PCBs, mercury, phthalates, and other contemporary toxic exposures, we must react much more quickly with legislative bans and protection for people on the front lines of environmental poisoning.

But I am not suggesting that we neglect proving the danger, or safety, of industrial chemicals. This is imperative. The problem is that we are testing them at the wrong time.

The United States has approved 60,000 chemicals for industrial uses that expose Americans in the workplace, in fence-line communities, and in company towns, and that poison us by leaching into our water and air. Regulations do not require companies to test the effects of such chemicals on humans prior to using them, and they don’t. We typically learn of health hazards only after people are exposed to them, and because environmental pollution exposes victims to a mixture of untested substances, teasing out and accurately characterizing the effects of any one chemical can be difficult. Moreover, many pollution-caused illnesses, such as lung cancer or mesothelioma, can take years or decades to appear, making them difficult to connect to a given chemical exposure.

But some nations, like those of the European Union, test industrial chemicals differently, before they are used. So should we. Rather than collecting, analyzing, and haggling over the sufficiency of data about a chemical’s relative safety after allegations of harm are made, the safety of any potentially toxic substance should be demonstrated before it is marketed and used.

Determining the safety of industrial chemicals before they go into use is an illustration of the precautionary principle. Unfortunately, it is not favored in the United States. And although it is not favored by corporations because it would add to the expense of research and development and delay marketing, pre-market testing in line with the precautionary principle would also save them (and the nation) the expense of bans, cleanups, and lawsuits. Most importantly, it would save the lives, health, and intellect of millions of poisoned Americans each year. As Swedish filmmaker Bo Widerberg once wrote, “Sometimes it doesn’t make sense to ask what things cost.”

It could, however, make a great deal of economic sense to make sure these chemicals are safe by testing them before putting them on the market, given the astronomical cost of health care and lost wages due to poison-induced illness—not to mention the expense of cleanups.

The lead industry relentlessly—and successfully—questioned the science showing that its products were killing children in their own homes. Industry so often resorts to the tactic of introducing doubt that, as later chapters in this book document, it has successfully halted or delayed the restriction and banning of clearly toxic substances.

For more than a half century the LIA internally acknowledged lead’s toxicity while publicly casting doubt on its dangers and blaming victims by ascribing illness to “improper handling.”

Meanwhile, public health practice focused on institutional accountability to ensure or improve American health. Its researchers, institutions, and government agencies sought to cajole, convince, or force organizations to comply with standards. Pressure was brought to bear, and eventually, the industry had to conform to lead-removal standards in order to minimize children’s exposure.

But as Columbia University historian and public health professor David Rosner and his coauthors point out in their article “The Exodus of Public Health,” a sea change in philosophy was taking place. Public health pressure on industrial polluters has been largely supplanted by a focus on laboratory science and the mantra of “personal responsibility.”34 “The field… abandon[ed] universalist environmental solutions—introducing pure water, sewage systems, street cleaning—and begin focusing on training people how to live cleaner, more healthful lives,” they write. By the advent of the Cold War, science and medicine became great levelers, allowing public health professionals to ignore social factors—including the racial segregation, poverty, inequality, and poor housing that had been the traditional foci of public health reformers only thirty years before—and explain disease without any of the disruptive implications of a class analysis.

By the 1970s, a powerful discourse of personal responsibility for health and disease placed blame on individuals and implicitly absolved corporations that marketed harmful products such as cigarettes and lead paint and polluted the nation’s water and air.35

The pressure to improve health is now placed on individuals as their behaviors are criticized, scrutinized, and sometimes demonized, in the hopes of modifying their behaviors into healthier ones.

Personal responsibility for health is important and a good concept in theory. However, a difficulty arises when avoiding disease requires avoiding lead fumes and dust, shunning tainted tap water, or evading mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants, because individuals have little power to control their exposure to industrial pollutants that frequently poison their workplace and neighborhoods.

Blame the Victim

When muddying the scientific waters no longer worked to hide how lead was killing and intellectually crippling children, the lead industry resorted to another tactic—deflecting blame onto the injured.

A wider realization of lead’s hazards coincided with a demographic upheaval in the aftermath of 1960s civil rights–era violence. This friction included rebellions, race riots, and the legally mandated integration of schools and housing. As whites fled to the suburbs, people who could not do so, primarily African American and Hispanic families, remained trapped in the cities’ lead-tainted housing. Lead exposure was morphing into a racially disparate poison.

The industry found this helpful to their cause as the purveyors of lead shifted the blame from their own promotion of a toxic product to a more nebulous malefactor: poverty.

In an internal memo Manfred Bowditch, the health and safety director of the LIA, wrote, “Aside from the kids that are poisoned (and we still don’t know how many there are), it’s a serious problem from the viewpoint of adverse publicity. The basic solution is to get rid of our slums, but even Uncle Sam can’t seem to swing that one.”36

In blaming manufactured racial disparities on “poverty,” Bowditch used what is still a popular ploy to evade industrial responsibility. In Deadly Monopolies: The Shocking Corporate Takeover of Life Itself, I discuss a public relations strategy in which pharmaceutical manufacturers fought bad press in the wake of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) regulations negotiated by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994.37 These laws, pushed through the WTO by the industry, force developing nations to adhere to Western pharmaceutical patents—and to accept high Western prices. These patents protect high corporate profits, but allow pricing above what the populace of countries like Thailand, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Brazil can afford.

They also allowed companies to abandon the development of medications they deem unprofitable, often medicines intended for diseases of the developing world. The TRIPS regulations even prevent countries like India from making cheap similar drugs that once helped to fill the pharmaceutical void in the developing world.

But pharmaceutical-company spokespersons and their scientists insisted that “poverty, not patents” was separating people in the tropics from the medications they need, often in articles that used quite similar wording and were based on deeply flawed studies.38

Similarly, when the LIA suggested that the nation could only eliminate lead poisoning if it managed to “get rid of our slums,” they were washing their hands of responsibility, as if leaded gas, lead paint, and lead-coated toys had spontaneously generated within slums rather than having been aggressively placed there via the industry’s vigorous promotion and political lobbying.

As the LIA statement shifted the blame onto poverty, for which it couldn’t be blamed, it portrayed lead poisoning as just another pathology of black Americans, and therefore of little concern to most Americans.

In addition, the LIA narrative argued that regulating lead was futile. As the industry knew, no one saw getting rid of slums as a feasible solution: “even Uncle Sam can’t seem to swing that one.”

But more than poverty trapped black and Hispanic families in lead-poisoned homes. Limited educational and career opportunities drove that poverty, and “slums” were the product of racial segregation. The law had once encoded segregation, but even after “separate but equal” housing legislation was revoked, racial and economic bias maintained housing segregation. Like most Americans, the industry understood that the nation was not eager to allow African Americans out of the slums and into white neighborhoods en masse, no matter how much handwringing attended the discussion of ghetto problems. In short, the industry’s stance that lead poisoning was “a public welfare problem,” not a lead-regulation problem, placed it far from the industry’s purview.39

But the LIA’s disclaimers revealed even more: a fresh blame-the-victim tactic. The term “slum” suggested the racial component of the problem, but Bowditch continued with language that made the racial characterization explicit. Lead was safe when applied and used properly, the industry suggested, but it implied that parents of color were slovenly housekeepers who did not use the paint in a correct, “safe” manner, who allowed unsafe levels of lead to accumulate in their dusty, dirty homes and did not monitor their children’s proper use of lead-painted toys and products. Of course this message still entailed a tacit acknowledgment that lead is dangerous, but the powerful invocation of ethnic parents as the real problem seemed to overshadow this misstep.

“Next in importance is to educate the parents,” Bowditch wrote, “but most of the cases are in Negro and Puerto Rican families, and how does one tackle that job?”40

“Uneducable” Negroes and Puerto Ricans

In casting black and Hispanic parents as uneducable, Bowditch tapped into a perception of people of color as too unintelligent to keep themselves and their children healthy and safe. He indicts black and Hispanic intelligence, not his firm’s aggressive marketing and duplicitous defense of toxic wares.

This mixture of corporate half-truths and racist blame-the-victim characterizations helped create an image of lead poisoning as a racial ailment that was of little concern to the average American.

This venal tactic resonated with many Americans, in part because by the 1970s lead poisoning was indeed a racial problem.

One might think that the end of de jure segregation would have made lead exposure democratic by yielding racially integrated neighborhoods and risks. Unfortunately, de facto segregation persisted, leaving people of color to deal with lead-imbued housing in the aftermath of white flight to the newly constructed, lead-free developments of the suburbs. Even middle-class people of color were affected. Redlining, credit inequities, educational and employment discrimination, and lower wages ensured that most marginalized minority-group members could not penetrate the pristine, pollution-free suburbs. But neither could African American doctors, lawyers, and corporate executives of color. They were barred by race, not income, from suburban homes not only in Southern states, but throughout the country. In upstate Rochester, New York, for example, Eastman Kodak chemist and executive Dr. Walter E. Cooper documented for the local newspaper his long odyssey to buy a home in the city’s completely white suburbs.41

The LIA denied that lead’s harms were as dire as public health researchers had painted them, and they successfully resisted the passage of legislation to limit lead exposure. This is because, as Lead Wars describes, the LIA was allowed to set its own limits for lead exposure. It misleadingly labeled these “standards,” as if they had been imposed by public health or legislative agencies intent on protecting children’s bodies and brains. In fact, they were created and adopted by an industry intent on minimizing its losses, and these “standards” reflected the interests of the industry, not of children’s health.

In the absence of legislation mandating lead containment or removal, landlords resisted paying for lead abatement, and some municipalities did not make them do so. Even in cities like Baltimore, where laws prohibited the renting of tainted homes, some landlords rented the homes anyway, or found it cheaper to abandon the properties, lead and all, as the city looked the other way and declined to prosecute them.

Even today, tainted houses in Baltimore and other cities are sometimes fobbed off on unsuspecting families who buy the homes at reasonable prices, unaware that they harbor lead. The new homeowners must then bear the costs of cleanup, abatement, and the possible lead poisoning of their family.42

Lead’s Effects on the Body

Between 1999 and 2004, U.S. African American children were 1.6 times more likely than white children to test positive for lead. Among the poisoned, black children were three times more likely to harbor extremely high lead levels of 10 micrograms per deciliter or higher, the level of lead poisoning that entails the most damaging health ills.43 And lead is cumulative, building up in the poisoned person over time.

Lead poisoning affects adults, who commonly suffer stomach, kidney, brain, and nervous system injury, as well as high blood pressure and behavioral problems. But children exposed to lead face worse consequences at the same doses. Lead harms nearly every bodily organ, and can slow the child’s growth. It can also cause hearing loss, headaches, weakness, muscle problems, memory loss, and trouble learning and thinking clearly. Angry, moody, or hyperactive behavior and other personality changes are common.

African American children’s greater lead exposure serves to depress their average IQ. In the 1980s, 35 percent of African American children who lived in cities had high blood levels of 10 µg/dL or higher, but only 5 percent of white children did.44

During this period, when average U.S. children’s blood lead levels hovered between 12 and 17 µg/dL,45 those suffering lead poisoning severe enough for admission to the hospital where I once worked often presented with acute poisoning. A fight to save the child’s life ensued, and coma and dramatic symptoms were common enough that doctors, out of necessity, were usually focused on keeping the child alive, not saving her intellect.

As I detail at length in Chapter 4, newborns and very young children suffer lead exposure even from food and water. But exposure escalates in toddlerhood, when a child is able to move about on his own, touching lead chips, and mouthing hands and objects contaminated with lead dust. Children who swallow lead absorb half of it; their gastrointestinal systems are larger relative to their body size than those of adults; as a result they absorb five hundred times more lead per exposure than adults.

To understand how lead harms the brains of children, one must first understand that their developing brains feature an exquisite sensitivity that magnifies the effects of very small exposures that would not harm an adult or even an older child. Many poisons, including lead, injure children in ways that vary according to their stage of development.

For now it’s just important to note that as the cells of the fetal brain develop, these neurons not only grow, but also blossom into a preordained complexity guided by an intricate, precise choreography. The choreographers are neurotransmitters, including endocrine hormones, which closely control when each cell will undergo differentiation and migrate to an exact locus within the brain.

Lead sabotages this precision, with portentous results: Brain cells may grow to the wrong size or in an incorrect configuration. They may migrate to the wrong portions of the brain, or fail to migrate at all. As a result, essential neurological structures and connections may become misshapen or may never appear at all, leading to brain damage that is irreversible.46,47 This damage continues long after birth, and its full import may not appear until the twenties, when the brain matures. Or even later: the corpus callosum that unites the two hemispheres of the brain, for example, is a late bloomer, often completing its maturation in a person’s thirties.

Moreover, this derangement of the brain’s growth and architecture doesn’t require acute, high-dose exposure; it is triggered by chronic, low-level lead exposure that may never be recognized, and may have no discernable symptoms for years, or even decades.48 This is precisely the sort of exposure that preferentially haunts the nation’s children of color.

Lead poisoning cannot be cured, but good nutrition, and in extreme cases, chelation—an inpatient procedure where children are given substances that bind excess lead so the body can excrete it—can lower lead levels. Chelation is not a cure-all, however, because it sometimes must be repeated, and sometimes it worsens the poisoning.

The damage is not confined to disorganization and malformation of the brain. Early exposure to lead also produces epigenetic changes that can reprogram genes, changing their expression in a manner that further heightens the risks of disability and a variety of disorders ranging from heart disease to colorectal cancer triggered by lead-induced DNA damage. The result may not become apparent until stress on the immune system later in adult life triggers failure.49 And since such reprogrammed genes can be passed from generation to generation, this harms not only the poisoned child but also his own children, an example of the complex interplay between genetics and environmental exposures.50

When this genetic transmission causes brain damage leading to lowered faculties, it occurs as a result not of innate inferiority, but of a chemical insult.

Moreover, a 2007 report in Neurotoxicology revealed that genetic damage caused by lead also sensitizes children to later neurological assaults, weakening the poisoned person’s ability to resist subsequent environmental injury.51

Unfortunately, the mind-destroying consequences of low-level lead exposure went unrecognized for many decades. In fact, lead poisoning was initially thought to harm children only when their blood level reached 15 micrograms per deciliter of blood (15 µg/dL). Later studies showed that children were also being poisoned at lower levels, so the toxic level was revised downward. Unfortunately, health policies in cities like Baltimore mandated no treatment for children whose blood-lead levels were less than 20 µg/dL, even though the threshold poisoning level was set at 10 µg/dL and experts argued for 5 µg/dL. Today, the CDC states that there is no threshold and no safe level of lead exposure.

Behavioral Fallout

The vanishingly low levels of lead that catalyze brain damage cause aggressive, inappropriate, and sometimes criminal behavior. Researchers blame pollutants like lead for a rise in disorders like ADHD, conduct disorder, and autism, which helps to explain why only 56.4 percent of lead-exposed Baltimore students graduate from high school. (The national rate is about 80 percent.)52

To better quantify the poisonous metal’s role in behavioral problems, the director of Fordham University’s Neuroscience and Law Center, Deborah W. Denno, conducted longitudinal studies in which she analyzed hundreds of biosocial factors that correlated with an increased likelihood of violent crime among 1,000 youths. After following the behavior patterns (compiled from such sources as their parents and school records) of 301 boys in the Pittsburgh school system, Denno measured their bone lead. After correcting for race, education, and neighborhood crime rates, the highest lead levels were found among boys who engaged in more bullying, shoplifting, and vandalism. Except for those boys with the lowest levels of lead in their blood, their behavior had worsened as they aged.

In another study, Denno followed 487 young African American men in Philadelphia from birth to age twenty-five. They all shared the same urban environment and school system. She assessed three hundred variables including blood lead, and found that childhood blood lead was the single most predictive factor for disciplinary problems and juvenile crime. It was also the fourth largest predictor of adult crime.53

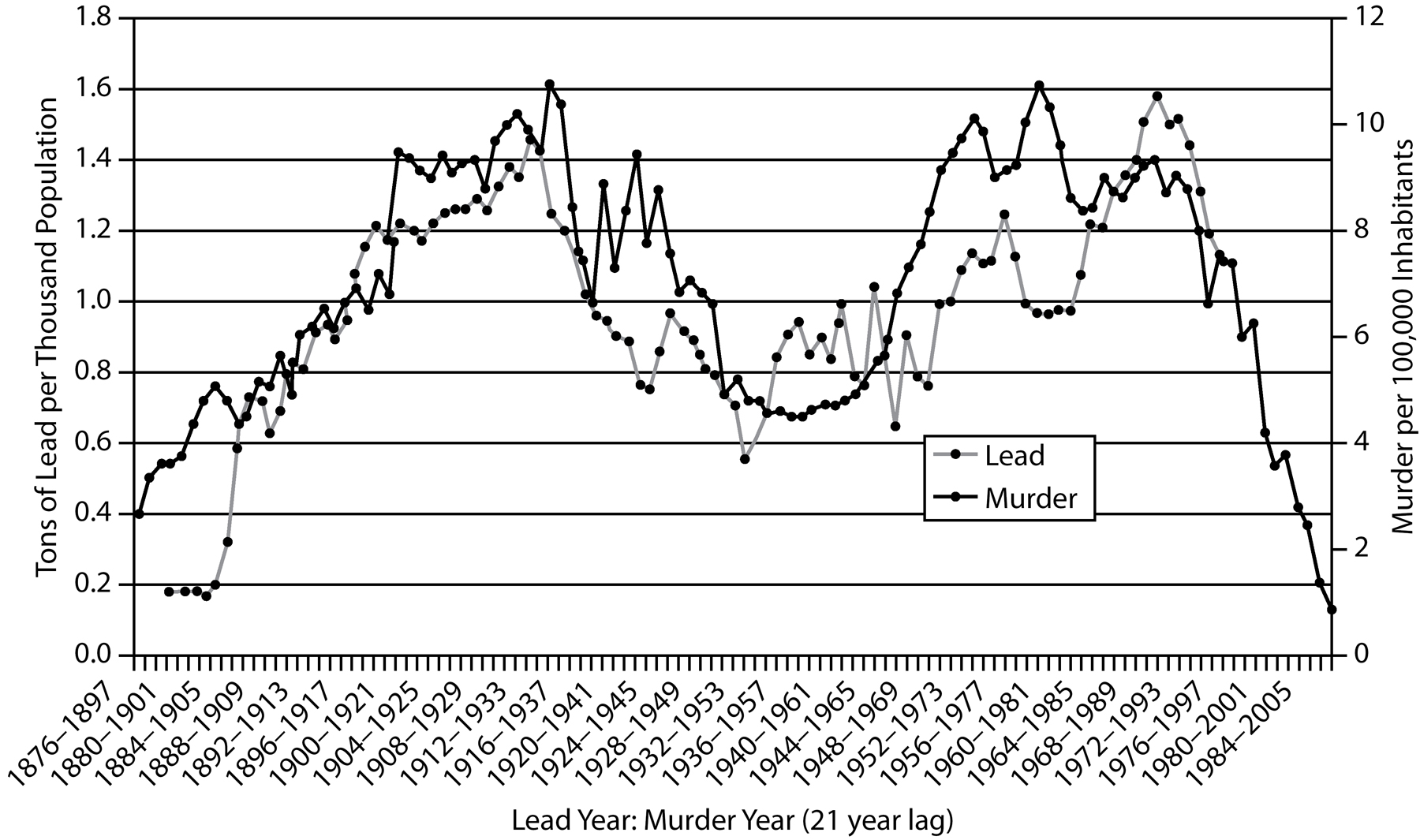

Others also blame lead for rising U.S. crime rates. In 2007, Amherst economics professor Jessica Wolpaw Reyes released her analysis showing that the reduction in gasoline lead was responsible for most of the decline in U.S. violent crime during the 1990s.54

In his 2016 Mother Jones article “Lead: America’s Real Criminal Element,” political blogger Kevin Drum details the evidence supporting lead as a driver of national crime rates.55 Like James Q. Wilson and Kevin Nevin, he correlates the rise and fall of crime rates with the addition and elimination of lead from gasoline. In broad strokes, as lead was banned from gasoline, crime fell, and it rose along with lead’s increasing presence in interior paint and toys. This is persuasive, although it doesn’t rise to the power of absolute proof: there are flaws in the data interpretation, many of which Drum himself discusses elsewhere.

Murder rates climb with rising lead-exposure concentrations, and dip as blood lead falls.

Criminal Element?

However, one methodological flaw that remains below the radar is the folly of equating arrest and incarceration with crime, especially when people of color are concerned. Being arrested or even convicted does not mean that a person has committed a crime. Neither is arrest a racially equitable response to behavior. For example, 92 percent of people arrested for marijuana possession in Baltimore in 2010 were African Americans, but this is because black Baltimoreans are more than 5.6 times more likely to be arrested for possession of marijuana than whites, even though marijuana use among the races is similar.56 Moreover, false arrests occur: In 2017, prosecutors dismissed thirty-four criminal cases after body-cam footage showed Baltimore police officers planting drugs at crime scenes.57

Especially for African American boys and men, whose behaviors are more strictly scrutinized and judged than those of whites, a wide spectrum of social frictions contributes to a greater chance of interaction with the legal system and can lead to arrest, injury, incarceration, and even death—even when no crime has been committed.

Several recent studies indicate that even black children are less likely than white children to be viewed as innocent. Black schoolchildren have been assaulted and arrested for politely contradicting teachers’ statements, for wearing braids, for playground fights, and for “inappropriate” clothing. One African American girl was arrested when her properly conducted, teacher-supervised chemistry experiment went awry, causing a small explosion in the classroom lab.

U.S. jails hold hundreds of thousands of people who are there not because they are guilty but because they are too poor to make bail or to commission the tests, including DNA tests, that would prove their innocence. Since 1989, DNA testing prior to conviction has proven that tens of thousands of prime suspects were wrongly accused, wrongly identified, and wrongly pursued.58 Stricter “stop and frisk” scrutiny of African American and Hispanic neighborhoods, racial disparities in the ability to make accurate facial identifications, errors, intentional or unintentional, by law enforcement, and the perception of black Americans as criminals all feed unjust incarceration.

Most people are aware that the Innocence Project and its offshoots have freed hundreds of innocent men from death row, most of them African American. Between 2000 and 2008, for example, between 50 and 70 percent of the incarcerated men exonerated by DNA technology were black or Hispanic.

Most of the convictions disproved by DNA evidence involve African American men wrongfully convicted of assaulting white women. “This is a crime that seems associated with many false convictions,” said Peter Neufeld of the Innocence Project in 2001.59

But most prisoners are not facing death sentences, nor do they have skilled Innocence Project lawyers to reevaluate their cases.

As a result, determined University of Michigan law professor Samuel R. Gross, tens of thousands of innocent people are trapped in jail: “If we reviewed [all] prison sentences with the same level of care that we devote to death sentences, there would have been more than 28,500 non-death-row exonerations in the past fifteen years rather than the 255 that have in fact occurred.”60

Finally, crime is multifactorial, and so are its putative chemical risk factors, including environmental poisons like mercury, manganese, and pesticides, all of which cause behavioral fallout, including impulsivity and criminality.

Slow Realization

Why did it take so long for scientists to realize that low levels of lead were causing rampant intellectual deterioration and dramatic behavioral problems? In 1982 David P. Rall, the former director of the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, wrote, “If thalidomide had caused a ten-point loss of IQ instead of obvious birth defects of the limbs, it would probably still be on the market.”61

In fact, thalidomide and its analogues have long been back on the market,62 but this fact doesn’t weaken Rall’s observation that we have been slow to recognize the invisible cognitive fallout from lead—and we have been even slower to act.

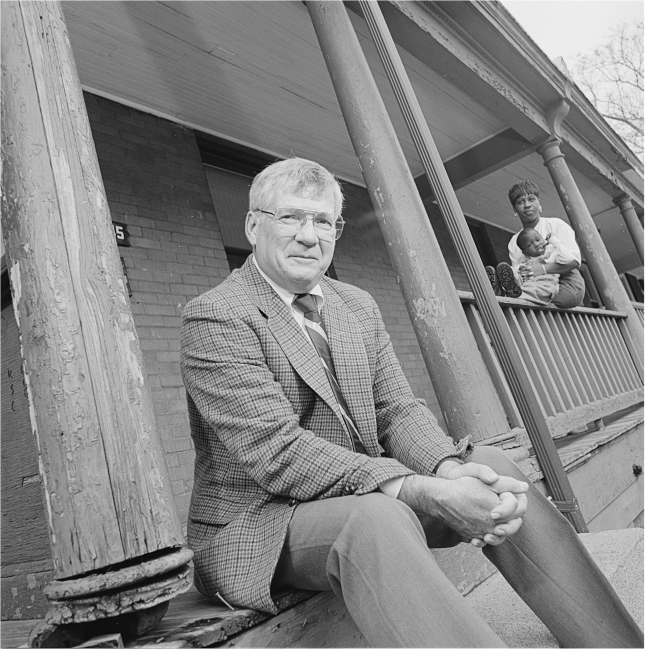

The late child psychiatrist and pediatric researcher Herbert L. Needleman devoted his career to removing the scourge of childhood lead poisoning. The son of a furniture salesman and a homemaker, he graduated in 1952 from the University of Pennsylvania medical school. After a short stint in the Army, he completed his medical training at a North Philadelphia community health clinic, where he spent his days treating children whose brains had been damaged and intellects short-circuited by exposure to high levels of lead.

Pediatrician Herbert Needleman spent a career documenting and combating insidious lead poisoning in urban U.S. children. (Courtesy of Jim Harrison)

His office window opened into a nearby playground where seemingly well children played every day. They had not been exposed to high doses of lead, but they lived in old, crumbling housing that harbored lead paint, so they were bombarded by low doses every day. Needleman wondered, was there an effect from these low, constant exposures to lead? He struggled to devise a viable way to find out—testing hair, blood, or fingernails was not accurate enough to register low doses. Bone biopsies were accurate but painful: taking them just to test a theory is unethical.

One day, Needleman gave a talk at a local African American church and afterward was approached by a young boy who clearly admired the doctor and sought to share his own ambitions. But as he listened, Needleman grew dismayed. “He was a very nice kid, but he was obviously brain damaged. He had trouble with words, with prepositions and ideas. I thought ‘how many of these kids who are coming to the clinic are in fact a missed case of lead poisoning?’”63 Needleman realized he was seeing the same signs of brain damage that his profoundly lead-poisoned patients displayed. Now it was more than an academic question: he had to discover whether low-level lead exposure was also destroying children’s mental capacities.

Tooth Fairy, M.D.

But how to test this? As noted above, hair, skin, and nail samples were not sensitive enough, and bone biopsies were accurate but painful, and therefore unethical just to satisfy curiosity. Needleman eventually hit upon a painless, accurate method: “Herb became the Tooth Fairy,” Dr. Bernard Goldstein recalled for the New York Times. Needleman realized he could test the baby teeth of affected children, and he began paying children in the city’s poor neighborhoods with disproportionately African American populations for each baby tooth that fell out. Needleman found that lead was cumulative, and that the average child had lead levels five times higher than those of his suburban peers. And an IQ gap of four points separated the children with the highest exposures from the lowest. These children who had not been suspected of being harmed by lead had relatively low IQ scores, poorer facility with language, and shorter attention spans.64 When teachers rated the exposed children’s classroom performance, a host of behavioral issues emerged, from attention deficits to behavior problems. Ten years later a correlation persisted between their childhood lead levels and reading delays.

Needleman was also acutely aware that he was fighting a racial scourge. When asked why he thought the government was reluctant to spend the funds necessary to completely eliminate lead from housing, he replied, “Well to begin with, it’s a black problem.”

The increasing focus on “personal responsibility” replaced accountability demands on the lead industry. Rather than hold manufacturers liable, the onus of avoiding harms increasingly fell on the victims, a cultural shift with profound legal implications. Cities sometimes failed to sue landlords who did not eliminate lead from their properties, worrying that if landlords were pressured to comply, they would simply abandon their properties, robbing a city of its tax base.

Instead, parents of poisoned children were told that it was their responsibility to keep their homes clean and free of lead dust and paint chips. Public health experts suggested abatement regimens that included training parents in the use of cleaning products like Spic & Span, implying that parents were failing to clean frequently or properly. Health workers also suggested that toddlers be confined to playpens to prevent contact with lead, a laughably unworkable—and unhealthy—strategy.

Full abatement of lead from the home was the only solution known to protect children, but its cost was rejected as prohibitive.

Needleman disagreed with this fobbing off of responsibility onto the injured, and he refused to accept that intervention was futile and too costly.

Moreover, he saw lead poisoning not as a discrete medical issue but as a symptom of social ills: medical and economic disparities that arose from racial discrimination.

And as Rosner and Markowitz describe in Lead Wars, he devised a visionary plan to address lead poisoning in this context. Under his plan, lead would be completely abated, and the work of properly sanding, repainting, and removing and replacing lead-tainted housing materials would be performed by unemployed workers under a federal program that resembled a latter-day Work Projects Administration. If followed, Needleman argued, his plan would remove the lead hazard while simultaneously addressing rampant unemployment in the lead-poisoned communities.65

In 1989, the plan’s price tag of $10 billion was rejected as far too expensive, although Needleman noted at the time that no one decried Congress’s plan to spend $11.6 billion to build new prisons.66 Since then, our government has spent far more than that amount dealing piecemeal with some of the aftereffects of lead poisoning, and that doesn’t include the cost of defending lawsuits against property owners and the unethical, shortsighted plans of institutions like the KKI. Even so, lead has still not been eradicated, and two of every three poisoned children in Baltimore are living in the same pre-1950 rental homes that Needleman’s plan sought to abate.

But Needleman’s findings were a key component in the 1974–1978 bans on lead in gas and paint, and his participation in various legal cases on behalf of poisoning victims made him an industry target. Accusations against him culminated in scientific misconduct charges brought before the federal Office for Scientific Integrity, and later, before his own institution, the University of Pittsburgh.

He was exonerated in both cases.

In a 2005 interview, Rosner and Markowitz wrote, “Dr. Needleman was asked whether the attack on his credibility was meant to scare off other researchers looking into environmental toxins. ‘If this is what happens to me, what is going to happen to someone who doesn’t have tenure?’ he replied.”67

In the past two decades, Maryland has passed a stronger law requiring landlords to cover or remove lead-based paint that’s peeling, chipping, or flaking. But properties are rarely monitored for compliance. And although the number of cases has fallen, at least 4,900 children were diagnosed with lead poisoning in the decade between 2005 and 2015 in Maryland alone. In reality, the number is probably much higher, because approximately 7 million lead poisoning tests processed nationwide by Magellan’s LeadCare Testing Systems underestimate lead levels, giving erroneous results.68

“If rich white kids were getting poisoned, there would be a law on the books that says ‘No lead in houses,’” lawyer Brian Brown told the Baltimore Sun in 2015.69 Today, Needleman’s $10 billion price tag looks like a bargain, even in adjusted dollars.

Blame the Victim 2.0

Young African American men are killed by police officers at nine times the rate of other Americans—1,134 were killed by police officers in 2015 alone.70 There is no salient justification for the disparity: black men are no more likely to be armed or aggressive than their white peers.

Police brutality is another risk to life and health in blighted communities of color. At least two of the noncombative, unarmed African Americans killed by police as they went about their daily routines were victims of something besides police violence: both Freddie Gray, twenty-five, and Korryn Gaines, twenty-three, suffered from lead poisoning.

In the 1990s, Gray lived from the age of two in a row house in Baltimore’s blighted, lead-soaked Sandtown-Winchester area, according to a 2008 lawsuit filed by Gray and his siblings against the property’s landlord. Average life expectancy in Sandtown is lower than in North Korea, and lead may be a factor. In his neighborhood and in several nearby census tracts, between 25 and 40 percent of children—that’s two out of every five—tested between 2005 and 2015 had elevated lead levels.71

As a result of being exposed to lead for two decades, Freddie Gray suffered developmental problems. The Gray family’s case was settled for an undisclosed amount.

In some newspaper accounts of his killing, I was surprised to read vague speculation that these lead-poisoning victims might have helped bring about their own deaths because of unspecified “behavioral problems” that are often linked to lead exposure. No such behaviors had been documented in them during the events, and this speculative claim recalls the blame-the-victim indictments of parents by lead-based industries.

Quite aside from the questions of guilt and innocence in deadly police encounters with peaceable, unarmed African Americans, we mustn’t use speculative medical scrutiny to demonize some victims of lead poisoning while winking at others. This bias compounds the victimhood of sufferers like Freddie Gray and Korryn Gaines by conflating their poisoning injuries with criminality.

This same animus drives some to criminalize the parents of lead-poisoning victims. In August 2015, Kenneth C. Holt, Maryland’s secretary of housing, community, and development, dismissed the plight of poisoned children by speculating that their mothers were deliberately exposing their own children in fraudulent attempts to obtain better housing. A mother, he said, might place “a lead fishing weight in her child’s mouth [and] then take the child in for testing.” He later admitted that he was not aware of any mother actually doing what he had suggested.72 Such demonization of the poisoning victims is not new: In their book Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution, Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner recount how a lead industry representative referred to the lead-poisoned children of Baltimore as “little rats” and their mothers as “overfecund imbeciles.”73

This baseless indictment of black parents illustrates a readiness to blame them, as well as a default stance of callous disregard for children’s health by the very institutions charged with protecting it.74

For all these reasons, our concerns about lead poisoning should be framed in a medical context, not a demonizing one, urges Ruth Ann Norton, who directs Green and Healthy Homes Initiative, a twenty-two-state agency dedicated to environmental health. “I don’t know what Freddie Gray did between the ages of three and twenty-five, but if he had been able to read well, had gone to school… [if] his family wasn’t just fleeing from one house to another, the likelihood of him not being on that corner would have been a whole lot better. We know that.… When do we want to stop dumbing down our kids?”75

At least 37,500 Baltimore children, nearly all of them black, were diagnosed with lead poisoning between 1993 and 2015, like Gray and his sisters. But only one in five black children is now tested.

In West Baltimore, Olivia Griffin’s children were raised in lead-tainted housing that slipped through the cracks of municipal lead monitoring. But she has now completed a job training program and found untainted housing through the Green and Healthy Homes Initiative. Still, her six-year-old son Nazir is paying the cognitive price for growing up in a lead-laden atmosphere. He “acts out a lot” and was slow learning to talk, she said. She took him to a speech therapist several years ago, but his speech still gets garbled sometimes. “You just have to be around him for a while so you can understand it.”76

The lead that once permeated the entire nation’s homes and air now persists in enclaves of color. These include Flint, Michigan, which garnered the nation’s attention when its people finally learned that their neighborhoods had been secretly flooded with poisoned water; East Chicago; and New York City, whose poisoned denizens still suffer in quiet desperation as a result of segregation, deception, and fatal greed; among many others.

Troubled Waters: Poisoning Flint

When water is pure, the people’s hearts are at peace.

—KUAN TZU

In 2014, Joe Clements, a seventy-nine-year-old who had been raised by adoptive parents, turned to DNA testing to seek out lost branches of his family tree. He’d lost many loved ones over the years, and he was eager to connect with his biological family. In the autumn his search bore fruit in the form of Randye Bullock, a half-sister, along with a whole new branch of his family.

The joy in their reunion was mutual, and Clements decided to move nearer to them. That fall he had begun life with his newfound family in a new city—in Flint, Michigan.

But just a few months after he arrived, aging but active and healthy, he began to sicken. He rapidly lost weight and suffered constant stomach pain and gastrointestinal distress. Fatigue washed over him while climbing steps or with the slightest exertion, and soon he lacked the energy to go out at all.

But Clements lived with more than pain and lethargy. His short-term memory deserted him, leaving him confused, emotionally brittle, and constantly irritable. He found himself unable to follow through on the simplest tasks. He couldn’t sleep, his hands shook, and sometimes, his legs did too. “I’m always exhausted and now I’m having lung congestion and memory loss,” he said. “I don’t even know the extent of damage to my body.”

Clements believed in drinking lots of water to keep his kidneys functioning well, so after he noticed his body weakening, he quaffed tap water even more liberally than he had before. And why not? City and state officials had repeatedly assured Flint families that their water was safe.77

However, younger members of his family were beginning to sicken as well, and unlike Clements, they had lived in Flint long enough to notice changes in their water. In the spring of 2014, yellowish water that smelled heavily of bleach had begun gushing from spigots.

The worst contaminant could not be seen or tasted: lead. Flint water’s lead levels were so high that it fell into the EPA’s classification for hazardous waste.

The service lines in Clements’s neighborhood were also made of lead. And because the water wasn’t infused with the necessary anti-corrosive chemicals, lead, iron, and chlorine leached from these aged, encrusted lead pipes into the already toxic tap water. By early 2015, its lead level was nineteen times higher than before Clements had moved to town.78 Moreover, despite the assurances to the people of Flint, General Motors was so worried about the corrosive water that it stopped using it at its engine plant out of fear of damaging its equipment.

Less than two years after he arrived in Flint, Joe was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive kidney cancer. A year after that, he was dead.

Lead exposure is suspected not only in Clements’s mental deterioration, but also in his kidney disease, says Michigan State University nurse educator Patrick Hawkins, Ph.D. “Even before the lead crisis, Flint residents had 2.5 times the national rate of kidney disease. No one knows precisely why. But I fear it will go much higher as we learn more about lead exposure. Lead moves out of the bloodstream and attacks organs.”

America’s lead crisis is a national threat to American bodies and minds. And as most now know, residents of the heavily African American city of Flint have been forced to drink lead-tainted water since 2014, the result of bureaucratic shortsightedness and deceit.

But today’s scandal is not Flint’s first brush with toxic notoriety. For at least eighty years, children growing up in the bustling industrial city center were surrounded by heavy metals that caused neurological disorders.

Then, as Michael Moore chronicled in his 1989 documentary Roger and Me, General Motors cars were displaced by more popular models from Volvo, Honda, and Toyota, and GM abandoned Flint, taking most of its tax base with it. In its wake, Flint was left an impoverished, poisoned city.

By early 2014, nearly half of Flint’s 100,000 residents lived below the poverty level. Forty-two percent still do, giving Flint one of the highest poverty rates in the nation for a city its size. In an effort to address the $9 million deficit facing Flint’s water supply fund, Governor Rick Snyder instituted an emergency management system, switching the city’s water supply from Lake Huron (via the Detroit Water and Sewer Department) to the Flint River, which was tainted from decades of use as an industrial dumping site for GM and the other industries that once lined its banks. Snyder rejected supplying the necessary corrosion protection for Flint’s lead pipes as too expensive.

Now, the city is enveloped in a public health emergency, with high levels of lead in its water supply and in the blood of its children. Although lead poisoning is devastating to adults like Joe Clements, it is much more deadly to children—with far smaller amounts causing IQ loss, hearing loss, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia, and even death.79

And as usual, race is a more powerful determinant of environmental exposure than socioeconomics.

Flint residents, news media, and health care professionals demanded that their discolored, foul-tasting water be tested and corrected, but nothing was done. Although the Flint water crisis is now acknowledged as racially disparate lead poisoning, it was originally described as a problem that plagued a “lower socioeconomic group.” And even after the racial disparity was documented, references to “socioeconomic” exposure persisted—sometimes even among those who elsewhere acknowledge its racial nature. For example, in late 2015, Flint pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha, M.D., became a medical hero when she first brought national attention to the lead poisoning in the American Journal of Public Health. She described the city’s blood-lead elevations as exclusively affecting “socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods.… As in many urban areas with high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and minority populations,” she wrote, “we found a preexisting disparity in lead poisoning.”80

Flint is a majority-minority city, meaning that more members of racial minority groups than whites live there. Most—65 percent—of its 99,000 residents are African American and Latino. Forty-two percent are poor.

“Socioeconomic status” (SES) is a variously defined term that refers to some interaction of social and economic factors—rather than to race. When a problem is ascribed to SES, many assume that the issue is driven by poverty and social conditions, such as lack of access to education, rather than by race or racial bias. As a result, socioeconomics is often set in opposition to racial bias, suggesting that health issues such as lead exposure are driven by economics or nonracial social issues rather than racial issues. In fact, socioeconomics and race are inextricably intertwined.

Residential segregation by race, an example of an institutional racism, has created racial differences in education and employment opportunities, which in turn produce racial differences in SES. In addition, segregation is a major determinant of racial differences in neighborhood quality and living conditions including access to medical care.81

Race also influences the “economics” component of socioeconomics: Any issue driven by poverty will necessarily have a disparate effect on marginalized ethnic and racial minority groups. Thirty-nine percent of African Americans are poor, as are 43 percent of Hispanics. Twenty-eight and a half percent of Native Americans and Alaska Natives live in poverty, nearly twice the rate of non-Hispanic whites.82 Furthermore, African Americans and Hispanics earn fifty-nine and seventy cents, respectively, for every dollar of income that whites receive. The racial differences in wealth, that is, in a household’s economic assets and reserves, are even more stark: for every dollar of white wealth, Asian households have eighty-three cents, Hispanics have seven cents, and black Americans have six cents.83

Because race is actually a component of the most pertinent definitions of socioeconomics, putting socioeconomics in rhetorical contrast to race is illogical. Instead, we must understand that race is an important component of SES.

Moreover, scientific reports have consistently demonstrated that race poses a stronger risk factor for the placement of environmental poisons than poverty. Poverty is a driver of environmental exposures, but race is a greater driver. Reflecting this truth, the definition of SES in public health spheres explicitly includes race as a factor. As Professor David R. Williams of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health notes: “All indicators of SES are strongly patterned by race.”84

Accordingly, although initial media accounts didn’t mention race but referred to Flint’s poverty as the key risk factor, with time, accounts acknowledged that race was the salient vulnerability.

“It Is Just a Few IQ Points…”