CHAPTER 4

Prenatal Policies: Protecting the Developing Brain

Even when she is not at work, Shirley Carter, the Anniston, Alabama, nurse whom we met in Chapter 3, devotes her time to improving the welfare of her poisoned neighbors. She had worked for Mothers and Daughters Protecting Childhood Health before she joined her husband in Community Against Pollution, a group he founded. Together they confront the EPA and industry to fight for her neighbors’ health care and for the cleanup of their town’s chemical morass. “You have to fight, you have to cover the ground you stand on, as my grandmama used to say.”1

But Carter is mired in a private battle as well, because her medical background serves to heighten some anxieties about living in Anniston’s hot zone. She breastfed her daughter because she wanted to give her baby the best possible start in life, conferring breast milk’s many nutritional and immunological benefits. As a nurse, she knew that breastfed babies tend to be healthier, and even smarter, than other children.

But in a cruel irony, Carter now worries that Anniston’s contaminants may have concentrated in her breast milk, and that nursing might have escalated her daughter’s exposure, jump-starting her behavior problems and catapulting her into the special education class in which she now struggles to learn.

It is not uncommon for parents in polluted communities of color to face similar dilemmas. Obeying public health urgings to breastfeed and provide a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and “brain food” like fish is usually the best way to give one’s children a healthy physical and intellectual start.

But what happens when toxic chemicals war with perinatal advice, making such mundane-sounding health mandates ambiguous or even dangerous?

Food for Thought?

Parents find other medical advice even trickier to follow. Doctors’ recommendations to give babies an early diet rich in fruits and vegetables, for example, seem like unassailable guidance. But they can expose children to brain-eroding pollutants lurking in unexpected places.

After birth, black and Hispanic toddlers suffer the highest rates of exposure from soil and dust, including that found in lead-tainted housing.2 But for most American formula-fed babies, the greatest lead and arsenic exposure risk emanates from an astonishing source—commercial baby food.

When the Environmental Defense Fund analyzed eleven years of federal data, it detected lead in 2,164 baby-food samples—from grape and apple juice to carrots, teething biscuits, and sweet potatoes. One of every four apple and grape juice samples exceeded federal lead limits of 5 ppb.3

Consumer Reports found that even one in ten samples of “organic” juices harbored more arsenic levels than federal law permits. Other tests detected lead in 20 percent of baby food samples—that’s one in every five.4

Formula-fed infants get most of their lead from water, but that changes as they age. Food is the greatest source of exposure for two of every three toddlers.5 Black children’s exposure to lead is much higher than other ethnic groups’ and comes from their immediate environment—water, housing, dust, and local industry. But African American and Hispanic children are exposed to lead-imbued food hazards in addition to their excess residential contamination.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimated that over 5 percent of U.S. children ingest more than 6 micrograms per day of lead, an amount that exceeds 1963’s federal lead limits*—though we now know that no level of lead intake is safe for children.

How does all this lead end up in baby food, of all places? Scientists blame the widespread use of lead arsenate insecticides, which are now banned, but which linger in the soil for decades, poisoning the vegetables grown in it and tainting the meat of animals fed with them.

Such poisoning, including from pesticides that linger in soil and water long after they have been banned, is so widespread that nine out of every ten Americans harbor pesticides or their byproducts in their bodies. Even types of produce that we think of as “healthy,” such as spinach and strawberries, are also widely tainted by pesticides. For example, six out of ten samples of kale are contaminated with Dacthal, or DCPA, which the EPA labeled a human carcinogen in 1995. But others, such as avocados and sweet corn, are relatively free of such pollution according to the Environmental Working Group’s “2019 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce.”6

“Avoiding all sources of exposure of lead poisoning is incredibly important,” said Dr. Aparna Bole, pediatrician at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. “But the last thing I would want is parents to restrict their child’s diet or limit their intake of healthy food groups.”

Thus, parents who strive to provide the recommended fruits and vegetables to their children face an impossible choice: the healthy food that promotes brain-building also exposes their infants’ brains to lead and arsenic.

Lead poisons children via a breathtaking variety of routes, from industrial air pollutants to food, paint, and gas.

This is not the only manner in which parents have to choose between optimal nutrition and keeping their babies’ brains safe.

Breastfeeding is a very important solution to this exposure, although it is not a universal one. Usually, new mothers can avoid or at least mitigate some brain-threatening exposures by breastfeeding. However, as Shirley Carter learned to her horror, other toxic agents are present in, or even concentrated in, breast milk, raising the question of how to safely give babies the benefits of breastfeeding.

A woman’s doctor should be able to advise her about this during prenatal counseling and well-child care. And fortunately, Ruth A. Lawrence, M.D., in her classic Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession,7 shows exactly how to avoid hazards while making an unassailable case for the mental and physical benefits of breastfeeding.

Lawrence, a professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology at the University of Rochester and the medical director of the poison center where I once worked, also details the relative popularity of different modes of breastfeeding in U.S. ethnic groups. Hispanic mothers breastfeed at the highest rate of any U.S. ethnic groups; African Americans breastfeed at a rate lower than both Hispanics and whites, but they have shown the largest increase over time. Asian rates vary greatly by ethnic subgroup, and statistics on Native American rates are too sparse to be reliable.

The fact that breastfeeding allows infants to escape at least some of the lead and arsenic exposures suffered by formula-fed babies may help to explain why exclusive breastfeeding is associated with higher verbal intelligence and thicker parietal cortices (the regions of the brain governing functions such as sensation, vision, reading, and speech) as well as better cognitive performance.8 But fish in a mother’s diet is also key, according to a 2006 paper published in the British Medical Journal. The research showed that omega-3 fatty acids in breast milk, known to be essential constituents of brain tissues,9 could at least partially account for an increase in the IQ of offspring.

A 2013 study published in the International Journal of Epidemiology also found that when they reached adolescence, the children who were breastfed performed better on full IQ tests, which measure verbal IQ and performance IQ.10

Beyond Genetics

If your brain works well enough to read a book, drive a car, and hold a job, thank your parents,11 and not just because they contributed its genetic scaffolding. Approximately 83 percent of the brain’s development takes place within the last three months of pregnancy and the first two years of life,12 so you owe your well-functioning brain to their early care, including constant daily attention to your diet, medications, and environmental exposures—before and after you were born.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, genetics alone does not create a functional intellectual capacity, explains Professor of Education Girma Berhanu of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “The fetus could have the genetic potential of a gifted child, but if the potential is not enhanced through proper nutrition and medical care, there is a possibility that the child’s development could be severely retarded.”13

The infant brain is composed of more neurons than an adult’s, not fewer. Like the process of painstakingly creating a sculpture from a featureless block of marble, refining the brain involves an early and precise process of “pruning”—the culling of superfluous neural connections. Furthermore, a baby’s cortical centers of sensation and higher thought are actually more richly connected, with more excitatory synaptic action, than an adult’s.

This helps babies to assimilate vast amounts of far-ranging information with ease. We lose this gestalt as we age but it lingers long enough to allow an infant to amass a prodigious amount of information and skills in a short time.14 Within a few years an infant progresses from a sleeping bundle to a toddler that walks, talks, and learns ten new words and asks dozens of questions a day—if her brain is properly fed, nurtured, and protected from harm, including environmental insults.

Thus, your cognitive future depends on the perinatal environment you are provided. Copious research reveals that many early toxic exposures and deprivations can be disastrous for the brains of the very young. If a child’s brain development is hobbled by poisons in his early environment, he may never catch up.

But poor parents often lack the resources necessary to enrich and protect their children’s health. As Barbara Ehrenreich observed in Nickel and Dimed, “In poverty, as in certain propositions in physics, starting conditions are everything. There are no secret economies that nourish the poor; on the contrary, there are a host of special costs.”15 And parents of color are more likely than others to be poor.

Some of the starting conditions and special costs that preferentially target poor families of color are biological, including the poisoning caused by built environments that remove much of the control over a baby’s earliest exposures from the hands of her parents.

For example, industrial pollution pervades housing, schools, water, and food—even baby food—threatening the brains and IQs of children from before their birth. And environmental and public health scientists have documented how the creation of food swamps, the targeted marketing of alcohol and tobacco products, and the siting of poison-spewing industries in poor areas of color all distort or short-circuit early brain development and thus intelligence, lowering IQ.

As we read in Chapter 1, the Flynn effect has documented a U.S. IQ rise of approximately three points per decade, Yet cognitive prospects now appear less rosy for the young, who are losing ground.16 As international studies like the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) suggest (as do the falling U.S. National Assessment of Educational Progress and SAT scores), U.S. students perform poorly, with less than a third (32 percent) of U.S. students having attained proficiency levels in mathematics in 2009. By comparison, half of Canadians and 63 percent of Singaporeans demonstrated such proficiency.17

The causes are likely to be multifactorial and to include poorly performing schools and our immigration policies. Although many express concern that allowing immigration from countries with lower levels of educational achievement18 leads to poorer cognitive performance in the United States, our laws exacerbate the problem when we deter immigration by the highly skilled from the “wrong countries.”19

But missing from most policy discussions of lost cognitive power among our young is a key factor: research now shows and quantifies early damage to their vulnerable brains by toxic heavy metals, industrial chemicals, and air pollution, damage that may begin in the womb, distorting behavior as well as cognition.

Even very low levels of exposure can wreak cognitive havoc.20

Young and Defenseless: The Vulnerable Brain of a Child

Chapter 3 notes that the young brain is exquisitely sensitive to chemical assault.

Why? Especially when it comes to poisoning, a child is not just a Mini-Me. Children differ dramatically from adults in their vulnerability to environmental poisons, including how toxic substances impair their brains and the manner in which their bodies metabolize chemicals.

From the moment a fertilized egg is implanted in the womb and throughout the first few years of life, a child’s nervous system experiences prodigious growth differentiation and development. Structures are formed and critical connections are established on a precise, unforgiving timetable. Toxic exposures can lower intelligence and distort behavior by destroying these brain structures or by preventing or distorting the necessary connections within them.

The exposures responsible for this damage can be frank poisons, endocrine disruptors (which interfere with hormonal signals that direct fetal growth), or chemicals of unknown function. Because the child’s developing body has neither mature immune protections against exposure nor the ability to repair itself, the damage may be irreversible and lead to loss of intelligence.21

The precise timetable of fetal development involves what Philippe Grandjean calls “critical windows of vulnerability.” A wealth of studies document how birth defects occur in concert with key developmental events. If a mother is exposed to a neurotoxin during a critical window, its effect on her child’s brain and thinking may be disastrous, although if the exposure happens a day later there may be no measurable effect. Developmental steps occur at specific times, and in a particular sequence at specific locations. As Philip Landrigan and his team write, “Implantation of the egg occurs on gestational day 6 to 7; organs begin forming on days 21 through 56; the neural plate forms between days 18 and 20; arm buds appear on days 29 to 30, and leg buds follow shortly after on days 31 to 32; testes differentiation occurs on day 43, and the palate closes between days 56 and 58.” Similarly, there are critical phases of brain development, which overlap in a complex and intricately coordinated manner, with each phase offering an opportunity for chemically induced disruption and damage if it occurs at the critical time.

During the last trimester of pregnancy, brain cells are formed at a rate of about two hundred cells per second. The new cells must move as far as 1,000 times their own length to find their exact positions in the brain and nervous system.

Every cell transmits electrical signals through its newly formed extension, or axon, and there is plenty of room for error: if they were placed end-to-end, the axons from a single budding brain would encircle the globe four times. These nerve cells communicate via electrical impulses and neurotransmitters across junctions called synapses, which function like on or off electrical switches. During the child’s first month of life, it spends most of its energy building its brain, including the creation of 1,000 synapses every second.22

The infant’s brain-building phases include

• making brain cells (neurulation and neurogenesis),

• moving cells to their proper location (cell migration),

• growing axons and dendrites to link nerve cells (neuronal differentiation and pathfinding),

• developing synapses or junctures of communication with other cells (synaptogenesis),

• refining or pruning the synapses (naturation), and

• forming the “insulating” tissue that surrounds nerve cells and enables rapid, efficient communication among them (gliogenesis or myelination).23

Early exposures to chemicals like lead and phthalates (dibutyl phthalate and bis [2-ethylhexyl] phthalate) can interfere with these tasks, harming the brain in ways that become apparent only in later life. (As a nasty grace note, many chemicals that harm the budding brain harm the developing reproductive system as well.)

Many insist that a physiologic filter called the blood-brain barrier is effective enough to bar such poisons from assaulting and harming the developing brain. But the BBB is imperfect. It helps to protect the brains of adults from harmful exposures, but it has not been fully formed in infants. Moreover, some common environmental chemicals, like arsenic, can damage it beyond functionality, even after it matures. As a result, some exposures have been demonstrated to be three to ten times more toxic to children than to adults. In other cases, a chemical that may not harm the adult brain at all can cause devastating injury to a child.24

Not only are children more sensitive to many chemicals that damage the brain, they are exposed to higher doses, pound for pound, than adults. One part per billion (ppb) of a chemical like benzene ingested from water, air, or food causes greater exposure to a child than an adult for multiple reasons:

• A child younger than six months old drinks seven times more water per pound of body weight than the average U.S. adult.

• Children between one and five years old eat three to four times more per pound of body weight than the average adult.

• Infants at rest breathe twice the volume of air, pound for pound, than resting adults.25

• Children two years old or younger have twice the relative body surface as an adult. Because absorption through the skin is a common route of many poisons, such as aromatic hydrocarbons, this multiplies the youngest’s exposure.

• Children explore the world by putting things in their mouths, and a bad taste doesn’t necessarily discourage them from doing so. Just doing what children normally do can increase doses of chemicals. Hand-to mouth transmission while crawling near the source of many contaminants on the floor and ground exposes them to chemicals that adults may evade.26

For specific environmental poisons, the differential effects on children can be dramatic. In Chapter 2, I explained that the same dose of lead that causes lifetime IQ deficits in two-year-olds produces no effect in adults. Many other common environmental exposures are much more dangerous for children than adults. For example:

Nitrate. Prolonged exposure to tap water with 20 ppm (parts per million) nitrate can kill an infant but has no observable effect on an adult.

Mercury. Exposure in the womb at 100 ppb (parts per billion)—that’s equivalent to one drop in 118 bathtubs—significantly increases learning deficits, while an adult exposed to that same dose suffers no measurable effect.

Radiation. Children exposed to radiation have a much higher incidence of cancer than adults exposed to the same dose.

PCBs. Levels of fetal PCB exposure that cause learning deficits that persist through adolescence cause no measurable effects on adults.27

In Chapter 2, I documented the neurological devastation wreaked by heavy metals like lead, which alone drains each U.S. birth cohort of 23 million IQ points annually. But other prenatal threats, like poor nutrition, sap cognitive power. So does tainted air, as well as exposures to PCBs, phthalates, pesticides, pathogens, endocrine disruptors, alcohol, tobacco, and other toxic industrial chemicals.

Some of these risk factors may be unfamiliar, but they are key to understanding the exquisite vulnerability of the young brain. Endocrine disruptors (ED), for example, change the development of the fetus in the womb by interfering with thyroxine and other hormonal signals that direct fetal growth.

ED chemicals harm brains by mimicking natural hormones. And since the body can’t distinguish these chemicals from natural hormones, it responds to the stimulus, often with disastrous consequences. Exposure to ED chemicals that mimic growth hormones, for instance, can result in gigantism. Alternatively, exposure to ED chemicals can trigger physical responses at inopportune times. Certain chemicals, for example, trigger insulin production when it is not needed, which can cause ketosis. Other endocrine disruptors block the effects of a hormone to excite or inhibit the endocrine system and cause insulin overproduction or underproduction.

There are many endocrine disruptors, but the most infamous example is diethylstilbestrol, or DES. This synthetic hormone was prescribed as a medical treatment for conditions such as breast and prostate cancers.28 As Robert Meyers’s riveting book D.E.S: The Bitter Pill recounts, doctors gave DES to pregnant patients between 1940 and 1971 in hopes of reducing the risk of pregnancy complications and miscarriage.29

Instead, DES crossed the placenta during pregnancy, and girls and women whose mothers took the drug are forty times more likely to develop a rare vaginal cancer called clear-cell carcinoma. The Food and Drug Administration subsequently withdrew its approval, and later studies showed that DES can cause a myriad of other medical disorders, including reproductive disease and infertility in both daughters and sons.30

Moreover, DES shows an especially insidious aspect of some toxic agents—the ability to damage the exposed person’s genes in a manner that is passed on to her children. This illustrates, yet again, the intersectionality of environmental and genetic risk factors.

Making matters worse, the effects of some endocrine disruptors like DES—including diminished intelligence, lowered fertility, and aberrant behavior—are not detected for years or even decades after the exposure. Studies also link endocrine disruptors to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and the burgeoning of autism spectrum disorders, as well as other brain abnormalities that translate into lowered intelligence—and lower IQ scores.31

The endocrine disruptor is just one class of what Harvard environmental health professor Philippe Grandjean calls “brain drainers.” These are chemical thieves of cognition that Grandjean, who is the head of the Environmental Medicine Research Unit at the University of Southern Denmark as well as a professor at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, says lower intellectual potential in exposed people, especially children. (This book’s Appendix includes a complete list of these chemicals.)

It’s likely that other prenatal brain-affecting chemicals exist but have not yet been recognized as such. But those we are aware of already pose a staggering threat to the brains and behavior profiles of exposed U.S. children, especially children of color, who are most often thrust into the proximity of brain drainers, even before birth.

Some insist that these chemicals are not dangerous or that they are present in concentrations too low to pose a health risk. Often, critics point to a lack of evidence that these substances are harmful. But absence of evidence sometimes reflects not harmlessness but a research vacuum. You’ll remember that unlike the European Union, where the precautionary principle reigns and chemicals used near humans must first be tested for safety, most U.S. chemicals are not investigated for their effects on human health until after an injury is suspected. So those who claim the chemicals are safe because no evidence of their injuries exists are wrong: until proper tests are performed, we simply cannot know their effects. Moreover, researchers and environmentalists speak of the difficulty in obtaining funding to investigate some exposures, an obstacle that is especially difficult to overcome in cases when exposure hinges on racial identity rather than economics.

Unfortunately, even after U.S. tests are performed, misunderstandings concerning toxicity—and even mythologies concerning poisoning—are rife. This means that the environmental harms to young children and fetuses have been dramatically underappreciated. For one thing, an exposure adjudged “safe” because it presents in amounts far too small to affect an adult can transform an infant’s brain development, his mental and behavioral functioning, and the course of his life.

Heavy-Metal Mortality: Vanished Children

In Chapter 2, I described how PCBs as well as common heavy metals and metalloids like mercury, arsenic, and lead wreak intellectual devastation on children of color, especially African Americans. But they do more than stultify existing children: they also kill unborn ones.

A 2017 report exposed “hundreds of excess deaths” of fetuses in Flint, Michigan, between 2013 and 2015 after the city switched to lead-poisoned Flint River water. Health economists Daniel Grossman and David Slusky found that between 218 and 276 more children should have been born, and that these “missing children” succumbed to fetal death and miscarriages caused by waterborne lead exposure32—a crisis that left so many dead that the city’s 2014 fertility rate plummeted.

The water-purity change was restricted to a specific period, allowing clear comparisons of Flint’s fertility and fetal health rates before and after the switch, when fetuses were exposed to tainted water in utero for at least one trimester. Because Flint was the only city in the area that switched its water supply, studies could meaningfully compare data with surrounding cities. No other Michigan cities recorded such a drop in fertility.

Unlike in other Michigan cities, the birthrate in Flint fell sharply, reflecting the many fetuses killed by the city’s environmental exposures, notably its lead-tainted water. Note: The red vertical line is at April 2013, which is the last conception date for which no affected birth rates are included in the moving average.

Even so, this count of missing babies is probably significantly underestimated because the investigation included only fetal deaths reported within hospitals, and did not include abortions or miscarriages that occurred before twenty weeks’ gestation.33

Flint was not alone. In 2013, the economists also found lead-driven fetal deaths rose as much as 42 percent, and birth rates fell in Washington, D.C., during the years 2007 and 2008, the same period during which the city endured its own lead crisis as levels rose in its drinking water. Lead levels in the District of Columbia had also peaked in 2001, then fell again in 2004 when public health correctives were put in place to protect pregnant women.34 The children born during the periods of high pollution suffered growth abnormalities, an increase in the prematurity rate, and lowered birth weights. By studying which neighborhoods were most affected, researchers were able to correlate the density of lead plumbing to both the markers of maternal blood lead levels and lead poisoning in children.35

The babies that survived didn’t emerge unaffected. The publicity about the nation’s racially stratified lead-tainted water makes the news that lead sabotages the brains of infants of color dismaying, but not completely surprising.

Doctors tell parents to avoid exposing their children to lead when possible: a clear strategy, but one that is hard to follow when lead’s presence in housing is hidden, as it was to the residents in East Chicago, Indiana, or when parents are actually steered to lead-tainted housing by health agencies, as they were in Baltimore.

Air Pollution

In Chapter 3, we saw how polluted air’s elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels trigger the hypoxia of asthma, which as studies show, leads to lower intelligence. Airborne heavy metals like lead and mercury as well as hydrocarbons, such as those in fuel exhausts and industrial emissions, also cause rampant brain damage to adults and children alike. These conditions compromise both the cognitive development and the function of a brain by depriving it of sufficient oxygen.

When it comes to air pollution, the developing brains of children fare the worst. Their greater lung surface area relative to their body size means that they suffer a greater relative exposure to noxious gases and suspended particles than adults.

For pregnant women and their fetuses, the damage is even more profound. Air pollution attacks fetal brains when they are at their most sensitive. Even small insults during crucial developmental windows can translate into fateful cognitive problems that persist for a lifetime.

How can air pollution doom the life—or the intellectual development—of a fetus? A May 2017 Time article, “Preterm Births Linked to Air Pollution Cost Billions in the U.S.,” gave the answer, but under the wrong headline: more important than the monetary losses is the fact that air pollution causes 16,000 premature births in the United States each year.36 We don’t know how many of these premature babies suffer lifelong mental disability, but we do know that pollutants derail the manner in which a woman normally delivers air to her fetus. Airborne pollutants also disrupt the endocrine system, which prevents the production of an important protein that regulates the pregnancy.

The air inside homes also threatens the brains of very young children. Carbon dioxide concentrates in poorly ventilated homes where it can kill sleeping families. By reducing oxygen intake, it also slowly erodes the brains of survivors, causing a laundry list of symptoms, including cognitive decline.

Vermin

We don’t usually think of microbes and other living things as causing pathological behavior or lowering intelligence, but we should. Infectious Madness: The Surprising Science of How We “Catch” Mental Illness documents the many ways in which infection—sometimes carried by vectors and microbes—causes mental disorders and disordered behavior. So does “The Well Curve,” a 2015 article in The American Scholar that discusses microbes’ important role in lowering intelligence. Chapter 5 of this book discusses in detail the cognitive costs of microbes that preferentially afflict people of color.

We have seen that mold, dust mites, and cockroaches have been shown to drive up African American and Hispanic asthma rates at a cost to intelligence that has yet to be quantified. However, despite a paucity of attention, microbes also pose a hypertension threat.37 Hypertension is most often caused by genetics, diet, excess weight, stress, and a sedentary lifestyle. But it can also be triggered by… rodents. Mice and rats can harbor Seoul virus, a type of hantavirus that, among other signs and symptoms, raises blood pressure.

In the mid-1990s, a high-profile Centers for Disease Control study investigated a deadly hantavirus outbreak among Native American populations in the Four Corners region, the symptoms of which were chiefly respiratory. The outbreak, which eventually spread to the general population, was found to be carried by infected mice.

Four years earlier, Gregory Gurri Glass of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health had reported that infection with different, rat-borne hantaviruses—Seoul virus—in “inner-city” populations is associated with an increased occurrence of hypertension.38 His team discovered that people living in poor urban neighborhoods infested with rats more often have viral antibodies indicating they have been infected by the virus, and connected undetected hantavirus infection to the high rates of hypertension among African Americans.

“Emerging diseases don’t just happen in Zaire, Kenya or Rwanda,” Gurri Glass told me at the time. “They are happening throughout this country now.” But a few years later he said that progress on the Seoul-hantavirus-hypertension question had stagnated because neither he nor New York City researchers on a parallel track had obtained funding to study the connection more extensively.

“The general view seems to be these infectious agents are not of particular relevance,” he lamented, noting that the U.S. Army ended funding of pertinent research. “We’re competing for resources with other societal ills.… I’m just hoping we can continue.”

But how is this virus-mediated hypertension pertinent to our discussion of intelligence? Hypertension is a well-known risk factor for physical problems like heart disease, and stroke. However, like asthma, it also sabotages intelligence: in addition to causing stroke, which often diminishes mental function, memory, and intelligence, hypertension erodes intelligence more directly. High blood pressure in otherwise healthy adults between the ages of eighteen and eighty-three is associated with a measurable decline in cognitive function, according to a University of Maine report in the journal Hypertension. Constantly elevated pressure weakens blood vessels including those in the brain, which can harm the brain by compromising oxygen delivery or heightening the risk of small brain injuries. Cognitive decline is a documented long-term effect of hypertension, even in children.39

Even worse, a 2012 report in Neurology suggests that hypertensive mothers may actually hand down their hypertension-induced cognitive decline to their children.

A Finnish study found that men whose mothers’ pregnancies were complicated by hypertensive disorders scored almost five points lower on tests of cognitive ability than men whose mothers did not have high blood pressure during pregnancy.40 “Our study suggests that even declines in thinking abilities in old age could have originated during the prenatal period when the majority of the development of brain structure and function occurs,” wrote Katri Räikönen, Ph.D., of the University of Helsinki.41

What’s more, one in ten pregnancies are complicated by hypertensive disorders like preeclampsia, which is more common and severe in African American women than whites, and is linked to premature birth and low birth weight, factors that are independently associated with lower cognitive ability.42

Parents seeking a solution to vermin and pollution exposure that could threaten cognition face an uphill road. Moving away from heavily polluted areas and out of dilapidated, vermin-infected housing is an obvious step, but can be an unaffordable one for low-income families, or even middle-class ones, due to mortgage redlining and stubborn U.S. housing segregation. However, even moving away from bus depots, manufacturing plants, and dry cleaners, which are sources of the volatile cleaning solvent trichloroethylene (TCE),43 provides limited protection. So does investing in HEPA vacuum cleaners,44 which control semi-volatile organic compounds such as phthalates, flame-retardants, pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) that otherwise persist in the air and dust.45

You can further reduce indoor pollution by using air conditioners and maintaining their filters while keeping the windows closed whenever possible, and certainly during high-traffic periods.46

If you own your home, keeping it vermin-free with the aid of professional exterminators is an expense you cannot afford to forego. If you rent, know your rights as a tenant: most cities have an agency like Legal Aid or a housing authority that offers free legal representation to tenants who cannot afford a lawyer. Enlist its help in your quest for safe, healthy housing. It may help you to move or to force your landlord to comply with health codes. You can discover the pertinent laws in your area by checking the Nolo site Renters’ & Tenants’ Rights at https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/renters-rights.

Municipal codes typically prohibit renting infested residential property and fine landlords for failing to maintain premises free of vermin. If this is the case in your city, you may be able to use the law as leverage to pressure the landlord to hire professional exterminators.

Waterborne Microbes

Waterborne poisons and microbes also contribute to fetal death and brain damage in communities of color and elsewhere.47

Lead is not Baltimore’s only intelligence-threatening pollutant. Its waters harbor microbes such as bacteria and copious amounts of suspect or disease-causing algae, like Pfiesteria piscicida.48 Moreover, the risk is much higher in some areas: residents of the Chesapeake Bay’s watershed are exposed to bacteria from sewage at more than 2,000 times the healthy levels. After storms, levels of fecal coliform bacteria from raw sewage and animal waste are extremely high in Baltimore County’s Back River. In 2001, they ranged from 640 to 2,135 times higher than the healthy levels.

The EPA and Justice Department sued Baltimore in 1997 over its malfunctioning sewage system, and municipal officials made a legal commitment to perform $900 million in repairs and upgrades.49 Even so, the water of the Back River continues to harbor at least one oxygen-deprived “dead zone” where nothing can live. Its sewage and microbial waste is joined by a witches’ brew of pollutants that are also known to affect cognition. “Our waters have a little bit of Prozac in them, a little bit of oral contraceptive hormone, a lot of caffeine,” summarized Hopkins professor Thomas A. Burke.

Meanwhile, experts from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health reassured residents that if they “limit their consumption of fish to the state’s guidelines, they should be fine.”

But because some areas are much more heavily affected than others, limiting exposure is not always possible. Nor is it practicable to expect this of people who fish not for sport, but for subsistence, supplementing their diet with a free source of quality protein. As David Baker, the environmental activist in Anniston wryly observed, “We’re fishing for survival: we’re not going to throw fish back.”50

Mercury-Tainted Fish: To Eat, or Not to Eat?

For pregnant women and new mothers, subsistence fishing presents another danger to their children’s brains: mercury.

Doctors urge pregnant women to enrich their diets, even before conception, with foods that will help build their baby’s brains. But in earlier chapters we have read how environmental poisoning prevents many poor African Americans and Hispanics from gardening for fruits and vegetables and discourages fishing for high-quality protein.

In urban communities, food swamps abound, creating the same dearth of nutritious food. Ethnic enclaves without supermarkets or farmers’ markets are often dubbed “food deserts.” However, the term “food swamps” is more accurate because the absence of healthy food in these regions coexists with an abundance of cheap, easily available, non-nutritious, sugary, and fatty fare, as well as the targeted marketing of potent forms of alcohol and of tobacco. Communities of color are often dependent on “corner stores” and bodegas where a handful of faded vegetables can cost more than an entire fast-food meal. Parents typically must pay for taxis to reach supermarkets and return with groceries, adding to their cost.

Such dietary danger zones are tied to income, but are more strongly tied to race. And when it comes to nutrition, infants, once again, are not just miniature adults. The large surface area of their intestines relative to their body volume often makes infants more vulnerable to toxins in food. They also metabolize foods and medications through different pathways than adults do. For example, babies younger than two years old should not eat honey, because unlike adults, their less acidic stomachs cannot neutralize the botulism spores it may contain and they may contract the fatal foodborne disease. Babies require special vitamin supplements; mothers of breastfeeding babies must adjust their diets and avoid certain medications. Prenatal counseling and nutritional advice during well-baby visits are essential in maintaining a baby’s mental as well as physical health.

However, when faced with pollution dangers, even doctors and researchers can find it difficult to give good advice regarding food. As a result, recommendations concerning the advisability of pregnant women eating fish from tainted waters vary based on the purity of the water, the species of endemic fish, and sometimes, by the sophistication of public health analyses.

Take mercury for example. Methylmercury is the form of mercury that causes neurotoxicity, but the relatively benign elemental form of mercury suffuses some waters. This leads some to assume that eating fish from the latter waters is safe. But it may not be, because some waterborne microbes transform elemental mercury into the brain-toxic methyl form by adding a few atoms—a methyl group, written as CH3. Several types of bacteria are responsible, notably sulfate-reducing bacteria and iron-reducing bacteria. There are many, but some common examples include salmonella, pseudomonas, and campylobacter, which are familiar because they cause food poisoning and other illnesses in humans. Other bacteria that carry the specific genes hgcA and hgcB can also transform elemental mercury into methylmercury as well.51 Additionally, some industrial wastes contain forms of iron that encourage mercury methylation when discharged into water.

Scientists also warn that pregnant women who consume tainted fish may face damage from industrial residues like PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) as well as from waterborne mercury. So do their fetuses.

Moreover, anglers may not realize that the size of the fish they catch is a key factor in poisoning risk. Poisons like mercury bioaccumulate—that is, they become greatly concentrated when larger fish eat smaller, tainted ones. Larger fish are more toxic than smaller ones from the same waters.

Formal studies have addressed the question of whether it is better for a pregnant woman to eat fish from tainted waters or to abstain and forgo seafood’s desirable brain-building nutrients. In 2004, the FDA and the EPA advised women of childbearing age to limit their seafood intake to about three servings a week during pregnancy to avoid exposure to trace amounts of methylmercury and other neurotoxins.

But this was followed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s 2007 study, which made a very different recommendation. Joseph Hibbeln found that the significant nutritional benefits of omega-3 fatty acids sacrificed by not eating enough fish outweigh the dangers of consuming mercury-tainted fish.52 His study of nearly 12,000 pregnant women in Great Britain found that the equivalent of two or three servings of seafood a week resulted in more intelligent children with better developmental skills, and he wrote in The Lancet that even more seafood in the diet might be advisable. “Advice that limits seafood consumption might reduce the intake of nutrients necessary for optimum neurological development.”

One researcher suggested to me that this is a concern for Asian Americans but not for African Americans, because there are no national data suggesting that they practice subsistence fishing. I was surprised to hear this, because I have seen it so often and known it to be common in areas where I have lived, worked, and visited. My own father and his inner-city friends often fished and sometimes hunted to help feed our family of seven.

And there is the plight of cities like Triana, whose residents practiced fishing to supplement their diets until pollutants rendered the fish dangerous to eat, as recounted in Chapter 3. But I understood that my anecdotal experience might not reflect national trends, so I looked for data.

As the skeptical researcher predicted, I did not find large national studies showing that African Americans engage in substance fishing that puts them at risk for mercury exposure. And I did find studies documenting it in Asian American communities. But this might mean that national researchers are simply not investigating the phenomenon in African Americans. “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” responded environmental sociologist Robert Bullard, when I approached him for a reaction.53

Despite the paucity of national data, some other studies, including analyses conducted in California and New York, looked at fish consumption by several racial groups and found that African Americans consume more high-mercury fish than the norm, writing, “Non-Hispanic blacks and women grouped in the ‘other’ racial category [whose ancestry is Asian, Native American, Pacific Islands, and from the Caribbean Islands] had significantly higher BHg (blood mercury) concentrations than did non-Hispanic whites.”54 In some studies, their consumption rivals that of Asian Americans, which is itself a highly diverse group.

Until more studies are done, we won’t know whether this pattern is repeated in larger swaths of the nation. In the absence of national data, some may be tempted to dismiss African Americans’ risk as unsubstantiated. But although unassailable proof is important, addressing known health risks in a timely manner is more important. We have seen what happened when a “prove it beyond every doubt before we take action” approach led to the annual loss of 23 million IQ points and $50 billion to lead.55

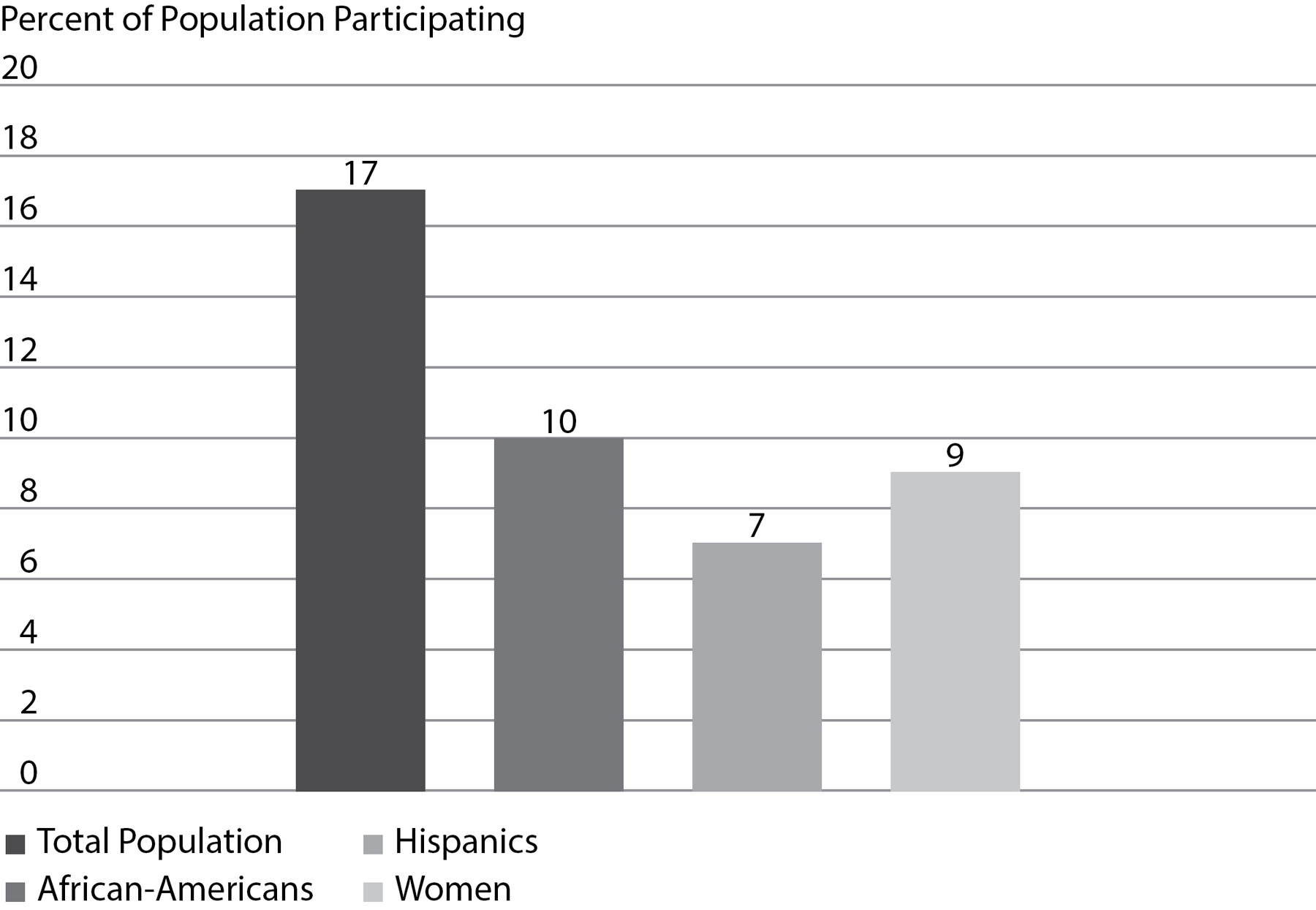

As this graph shows, significant numbers of African Americans engage in subsistence fishing to supplement their diets, as do Hispanics.

The stakes are so high that the precautionary principle applies here. We must address the risks of waterborne mercury.

Fortunately, the EPA’s inspector general released a report in April 2017 castigating it for failing to adequately protect vulnerable populations, including African Americans, against contaminated fish.56 This acknowledgment is a necessary first step in addressing hidden risk.

Until national data that clearly indict or exonerate mercury exposure are collected and analyzed, one solution is to take a more individual approach to detecting mercury in prospective mothers. In 2017, a Danish study determined that testing the hair of a pregnant woman for mercury on the day of her first ultrasound can help reduce fetal exposure,57 because it permits her doctors to inform her if her baby is at risk, monitor and treat her appropriately, and provide an incentive for avoiding additional mercury. Doctors should consider a hair test for minority mothers, and any woman who is worried about mercury risk should request such testing.

Parents themselves can undertake another important solution by choosing varieties of fish that are known to be low in mercury. The Food and Drug Administration lists shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish as the four fish with the highest levels of mercury—avoid them. Instead choose light tuna (avoid white albacore tuna, which has a higher mercury content), salmon, pollock, catfish, shrimp, and mackerel (the smaller mackerel fish, which will have lower concentrations of mercury). You should also avoid fish that are salted, as pollock often is.

Tilapia is inexpensive, rich in vitamins, and low in mercury, but many avoid it because of misinformation circulating on the Internet. There is no scientific evidence that “bacon is better” for you than tilapia, as the Internet alarmists claim: a single study’s conclusions were taken out of context. More information is available by searching factcheck.org.58

The FDA further recommends limiting yourself to about twelve ounces of fish a week, the amount contained in two average meals, but pregnant women should seek guidance on this from their physicians.

Prenatal Peril

The mercury exposure/omega-3 fatty acids risk-benefit ratio is just one aspect of quality prenatal nutrition related to intelligence.

The poor nutrition so common in urban food swamps also potentiates other causes of lowered intelligence, notably lead poisoning. But a high-nutrient diet that includes varied fruits and vegetables offers some protection against the ravages of lead poisoning because a wealth of nutrients, like the calcium in canned salmon, sardines, leafy green vegetables, and milk, makes it harder for lead to be absorbed and strengthens the immune system. Iron, found in beans, lentils, lean red meat, raisins, prunes, and other dried fruits also blocks lead absorption.59

In addition, pregnant women, new mothers, and their children are too often deficient in amino acids, iodine, calcium, iron, phosphorus, and vitamins such as folic acid, which prevents cognition-sapping neural-tube defects. A varied, balanced diet and supplements will further protect the infant brain.

Although all developing fetuses and children need similar nutrients and similar protections against poisons, race and ethnicity sometimes complicate acquiring them. We are rarely speaking of physiological differences, although there are a few, such as the increased need of dark-skinned people, like some African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics, for additional vitamin D supplements. (Vitamin D deficiency is more prevalent among African Americans, even young, healthy ones, in part because their darker skin blocks sunlight’s UV rays, which are necessary for our bodies to manufacture vitamin D, and are relatively scarce at North America’s higher latitudes.)60

Most racially disproportionate nutritional risks are created by environmental and social pressures. Unfortunately, however, doctors do not always include environmental advice when counseling the pregnant women and mothers who most need it. In one study, monitoring found about one hundred different toxic pollutants including lead, mercury, toluene, perchlorate, bisphenol A, flame retardants, perfluorinated compounds, organochlorine pesticides, and phthalates in pregnant women, with forty-three such chemicals found in every woman tested. Yet only 19 percent of these women’s doctors had discussed pesticides and only 12 percent discussed air pollution, even though their dangers are well established. Only four out of every ten doctors said they routinely discussed such contamination with pregnant women.61

Only 8 percent of physicians warned their patients about bisphenol A (BPA) and 5 percent advised avoiding phthalates. Nine percent of the doctors—fewer than one in ten—told their patients about the brain-draining polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) often found in fish.62

Why the silence? Many doctors say their priority is to protect pregnant women from more immediate dangers, and that warning them about environmental risks may create undue anxiety. Although Dr. Naomi Stotland of San Francisco General Hospital knows that her low-income patients on California’s Medicaid program are probably at higher risk of toxic exposures, she told Scientific American that she didn’t discuss environmental health with them for a long time. Why? “The social circumstances are so burdensome. Some colleagues think the patients are already worried about paying rent, getting deported or their partner being incarcerated.”63

Thus, unborn children of color are awash in environmental hazards about which their doctors remain silent.64

The situation is even worse for women who do not receive the recommended level of prenatal care. Women without access to prenatal care often know far too little about nutritional risks to their unborn children. Fewer than one fertile woman in three knows, for example, that taking prenatal folic acid supplements reduces birth defects and eliminates spina bifida.

Cultural risk factors threaten the infant brain as well. Some folk remedies such as greta and azarcon teas, taken for indigestion, contain lead, and so do some candies and delicacies from countries like Mexico and China that are imported and sold cheaply in dollar stores or bodegas to people of all ethnicities. Nzu and poto, nostrums for morning sickness, can contain dangerous levels of lead as well.

Then there are the various nonfood items that are consumed, sometimes in large quantities, by those with pica. Pregnant women are among those who sometimes satisfy cravings for chalk, starch, or even mud, all of which can harbor dangerous pollutants and microbes. “Calabash chalk” a natural material composed of fossilized seashells, is consumed by pregnant women in some West African cultures and in parts of the United States as a treatment for nausea. It is found in North American ethnic stores as well, but it can contain high levels of lead and other risky adulterants.65

Cleaning House

To minimize the foodborne poisons that threaten your fetus or baby, eliminate as many as possible from your household. In order to reduce exposures to bisphenol A (BPA), avoid buying food and beverage cans with resin liners. This is especially important in light of a New York City study that measured prenatal and postnatal BPA exposure until age five in inner-city African American children and found that children with the highest BPA exposure levels showed more problems on tests that measured emotional reactivity and aggressive behavior.66

Read the labels of your plastic containers before buying them to be sure they do not contain chemicals called phthalates. In fact, it is a good idea to avoid buying any foods packaged in plastic and to avoid processed foods as much as possible. Food co-ops, farmers’ markets, and stores that carry organic fare may offer the option of paper containers or allow you to bring your own.

Few people have the time to cook all their meals from scratch, but many people find making the week’s entrees in advance and freezing them until use allows them to control sugar, fat, and additives, while saving time in the long run.

Cosmetics contain suspect chemicals, too. Read the label of cosmetics and avoid using those with phthalates, as well as lipsticks that contain lead: look for additives that contain “plumb” in their name. Cheaper foods and candies purchased at “dollar stores” sometimes come from countries where food can contain unacceptable levels of lead, so this may not be the best place to save money: pooling funds with friends to buy high-volume cases of domestic foods and treats at big-box stores may be safer.

It is important to clean in order to minimize vermin and tracked-in pollution, but many cleaners and pesticides carry their own host of toxic problems, so try using baking soda, vinegar, and nontoxic commercial cleaners instead of toxic products during pregnancy.67

Fetal Alcohol: A Hidden Scourge?

In June 1998, two weeks after completing a yearlong fellowship at Stanford University, Serena walked into a bodega on 147th Street, a block from her new apartment in pre-gentrification Harlem. Repulsed by the fumes from young smokers as she waited her turn in the dingy, claustrophobic storefront, she watched a young man buy a forty-ounce bottle of malt liquor without being asked to produce ID. Another requested “two loosies” and was surreptitiously handed a couple of cigarettes in exchange for a dollar.

Intimidated by the sketchy characters loitering about, she tried not to stare at the clerk and wondered whether it was safe to say anything. But as she looked away, a lurid poster just beneath the counter riveted her attention. Could she be seeing correctly? The graphic ad featured a color photograph of two rhinoceroses copulating over a slogan proclaiming the virtues of an obscure malt liquor brand. She was shocked into silence until she heard giggling and saw two young boys pointing at it. Then she became angry. Adults might not notice the poster, but it was low enough to be directly in the line of sight of the children. “What is this and why is it here?” she demanded. “Don’t you know that these children can see it?” A shrug and a smirk accompanied the clerk’s bored response: “I don’t know, lady; I’m not the owner.… Are you going to buy something?”

“Every block in the ghetto has a church and a liquor store,” Dr. Walter Cooper, retired Eastman Kodak executive and NYS Regent emeritus, once told me. Perhaps it’s inevitable that growing up in an environment saturated with enticements to dangerous addictions would lead to African Americans’ suffering the nation’s highest rate of smoking and second highest rate of fetal alcohol syndrome.

Over a decade after Serena’s experience, even with gentrification in full swing, lurid alcohol shops continued to haunt Harlem neighborhoods. In 2011, even the historically black neighborhood of Mount Morris Park, home to $2 million brownstones and $3 million apartments, became the site of a nuance-free liquor store replete with a roll-down steel gate, Plexiglas customer barriers, and lurid neon sign decried by its appalled neighbors as “ghetto.”68 They complained to the New York Times that they knew a liquor store was coming, but they had expected a tony wine shop, not a bulletproof dive hawking Night Train.

What’s for sale in such establishments? Something you’re hard-pressed to find elsewhere: cans and bottles of malt liquor share the refrigerated case with Budweiser and Beck’s, but they deliver the alcoholic wallop of a bottle of wine, not a can of beer. Fortified wines radiating colors not found in nature taste like candied gasoline because they’re tailored to the tastes of the young, including underage drinkers. By the mid-1960s, liquor companies began marketing their high-alcohol malt liquor to African Americans.69

Sexualized posters and labels sell misogyny with the alcohol, as Ice Cube urges, “Get your girl in the mood quicker, make your jimmy thicker,” and old-school Billy Dee Williams winks and says, “Works every time.”

Although some middle-class white youths also partake, they usually must visit the ’hood to procure these drinks, some made by vintners that would be familiar to their parents.

MD 20/20, so potent that it is referred to as “Mad Dog” on the street, is produced by the Mogen David Wine Company, better known for its kosher dessert wines. Night Train Express, 17.5 percent alcohol, hails from the sun-dappled California vineyards of Ernest and Julio Gallo.

But you won’t find these hardcore libations among the sedate table wines on their websites, nor on restaurant wine lists. They’re not for discriminating palates but for those who want maximum alcohol at the lowest prices, and they are fortified not with vitamins but with extra alcohol, keeping poor communities of color steeped in liquor, on the cheap.

Such potions were invisible when I lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Village, and Palo Alto. But on my infrequent forays into East Palo Alto, then 81.8 percent black and Hispanic, I often saw half-nude women posing in ads hawking malt liquor and fortified “ghetto wines” just as they did in Harlem, Baltimore, and Chicago’s minority neighborhoods.

For decades, these communities have been steadily saturated with come-ons for addictive products tailored to the minority market. Between 1986 and 1989, 76 percent of billboards in African American neighborhoods of Baltimore advertised alcohol and tobacco, compared to only 20 percent in white communities. In Detroit, the ratio was 56 percent to 38 percent, and in St. Louis, 62 percent to 36 percent. Similar patterns are found in New Orleans, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco.70

Tobacco billboards are now widely banned, but those advertising liquor remain, and they are supplemented by depictions in rap videos, smaller posters plastered everywhere, films, television shows, and paid celebrity spokespersons.

The alcohol-soaked environment of minority neighborhoods is replicated in the womb, where it endangers unborn children.

The easy availability of liquor in African American communities leads to high rates of fetal alcohol effects (FAE), a less severe condition than fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS),71 but one that is also caused by drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Alcohol’s devastating effect on African American fetuses is a problem that psychiatrist Carl Bell says “has been hidden in plain sight.”72

In fact, says Bell, who has studied the rates of undiagnosed FAE and FAS for decades, “FAE is the largest preventable public health problem in poor African-American communities.”

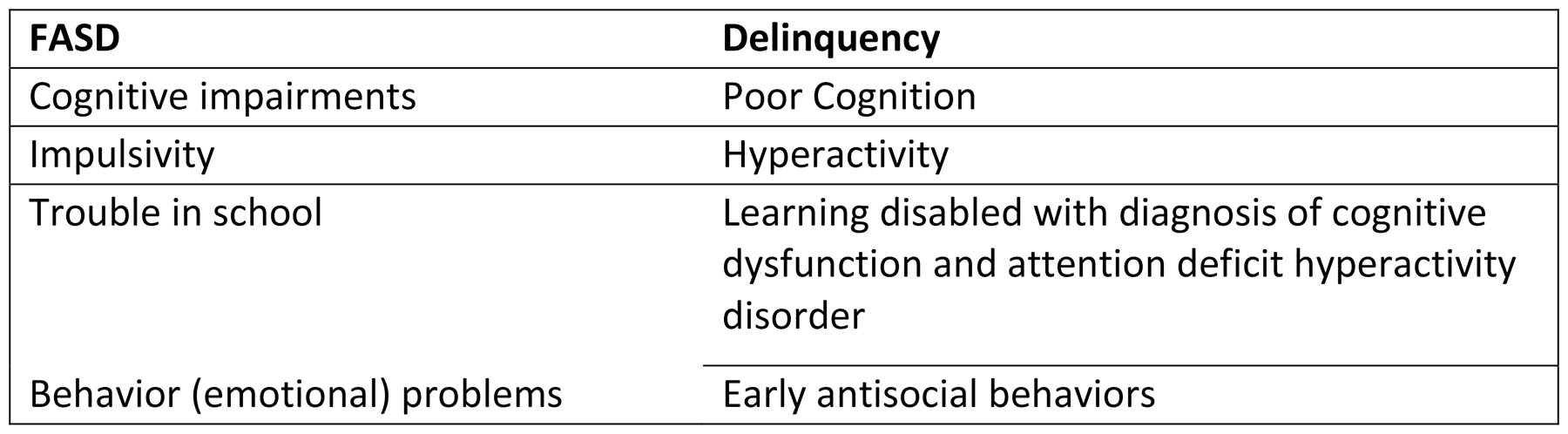

Alcohol is a teratogen, an infectious, pharmacological, or other biochemical agent that acts during pregnancy to produce birth defects or dysfunction. We’ve known since 1973 that when a pregnant woman drinks, her child may emerge with fetal alcohol syndrome, marked by unusual facial features and brain damage. Although the characteristic facial abnormalities of FAS are its most apparent symptoms,73 brain scans performed on victims of FAS reveal damage to the brain’s white matter and abnormal connections between the frontal occipital lobes, areas that govern executive functioning and visual processing. Accordingly, victims of the syndrome are faced with a variety of congenital defects, including diminished intelligence, low IQ, mental retardation, hyperactivity, difficulty concentrating, poor memory, learning difficulties, speech and language delays, and poor reasoning and judgment.

Children with FAS suffer delayed language and motor skills, their short-term memory is compromised, and they are often impulsive, acting with a lack of foresight about their actions’ consequences. Sixty percent of adolescents with FAS are arrested or have other trouble with the law, such as shoplifting, and disruptions in school. They suffer from low birth weight and a slowed growth rate as well as heart, eye, and genitourinary malformations as well.74

Less severe manifestations of prenatal alcohol exposure include fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND). People with ARND might have intellectual disabilities and problems with behavior and learning that cause them to perform poorly in school, as well as difficulties with math, memory, attention, judgment, and poor impulse control.

Many affected people cannot handle the social interaction and ordinary tasks of everyday living. As a whole, these mental and behavioral deficits set children up for failure in school and the workplace through no fault of their own.

Carl Bell, a Chicago child psychiatrist, has extensively documented the previously unsuspected extent of fetal alcohol disease in African American children. (Courtesy of Carl Bell)

The symptoms of FAS are often mistaken for other forms of behavioral disorders that are commonly ascribed to minority children. But subtleties distinguish the signs and symptoms of these disorders from FAS. Carl Bell notes that three of every four youths in Illinois’ Cook County Temporary Juvenile Detention Center had difficulty with reading, math, communication, memory, explosive behavior, hyperactivity, poor attention skills, and social judgment. Most had other diagnoses, but FAS should have been considered in such cases.

Early diagnosis and therapy can dramatically increase a child’s chances of success in life, but far too few FAS children are promptly diagnosed and given the support that could enable them to tame their behavior problems and fit into society.

Although the national rate of FAS is two to five percent of children, Bell and his Chicago colleagues documented a staggeringly high FASD rate of 57 percent in a Chicago clinic that served African American patients.75 Their symptoms and medical history were consistent with the spectrum of fetal alcohol disorders.

It’s entirely possible that FAS alone contributes significantly to the lower average IQ of U.S. African Americans. However, we require larger studies of FAS rates among African Americans nationwide to know for sure.

How could this FAS epidemic among African Americans fall below the public health radar, especially when, as Johns Hopkins University professor Ellen Silberberg points out, “The African American alcoholism rate is lower than the national average”?

Because several factors tend to veil alcohol-related brain damage among African American children:

Most African American mothers of babies suffering from FAS/FASD are not alcoholics. Health workers suspect and often screen for FASD in the babies of alcoholics, but not necessarily in the babies of women who are moderate drinkers. Moreover, even exposure to alcohol only during the third trimester of pregnancy can trigger FASD. But this is precisely when some mothers erroneously assume that their baby is fully formed and that a glass of wine or an occasional cocktail is safe. There is also a higher prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome, although African American women are less likely to drink than whites.76

Mothers of FAS/FASD babies are young and tend not to know they are pregnant until two months have passed. During this time they may have engaged in social drinking that puts their baby at risk.

Health workers focus on Native American mothers. The high known rate of FAS in Native Americans leads to stricter scrutiny of their infants, but not of African American babies. Although screening for FAS is important, we must guard against the firewater myth, the belief that biological or genetic differences make American Indians, Alaska Natives, and other First Nations people more susceptible to the effects of alcohol, including alcohol problems such as FAS. Aside from being plain wrong, the futility inherent in this myth is a disservice to Native Americans, a study by University of Alaska psychologists found, because “believing that one is vulnerable to problems with alcohol may have negative effects on expectancies and drinking behavior… and have negative effects on attempts to moderate drinking.”77

No law requires that U.S. newborns be screened for FAS. This means that many infants are never diagnosed, and Bell documents that as they age, their intelligence loss and behavior problems are ascribed to other causes.

Immediate protective measures have not been instituted. We swab newborn babies’ eyes with silver nitrate to protect against possible damage from gonorrhea during birth. Most mothers don’t have gonorrhea, but this offers safe, cheap, and effective insurance against blindness for the minority whose mothers do. We need similar protective steps for babies exposed to alcohol in utero.

Bell thinks that such a simple, safe protective treatment exists. Based on evidence that it protects against FAS, he and others recommend that we explore the option of giving women choline, a vitamin-like nutrient that has been shown to be protective against FAS in his and others’ studies. If proven effective and safe in wider studies, he urges that we adopt postnatal choline, that it be added to prenatal vitamins, and that its current dosage in conventional multivitamins should be increased.

Some studies also offer evidence that choline may protect against another brain thief, Alzheimer’s, which African Americans suffer from at twice the national rate. Researchers at the University of Colorado at Denver propose that a form of choline may help prevent the development of autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia as well.78 Choline seems to be a nutrient that demands further investigation.

Although the consequences of FAS are dire, its victims are not doomed, because protective factors and early intervention can ward off signature life failures like dropping out of school, chronic unemployment, and jail. With the proper diagnosis and support, people with FAS can enjoy success.

Just ask Morgan Fawcett, the young Tlingit Alaska Native who founded One Heart Creations to raise awareness for FAS and who travels the nation giving concerts and benefits. Fawcett is also a flutist who was honored as a Champion of Change in a 2011 White House ceremony. Initially, he recalls,

I had no clue that I was struggling because parts of my brain didn’t develop. I was struggling because my body didn’t develop right.… My mother drank during pregnancy. But just because she drank during pregnancy doesn’t make her a bad person. There’s a stigma placed on mothers. When it comes to fetal alcohol there are only victims, never perpetrators. Even with my disabilities because I have support we are doing things differently, I’ve become profoundly successful. I’m a 4.0 student in college because we were able to adapt my learning style to my coursework.79

The disastrous effects of FAS can be mitigated and even prevented, says Luther K. Robinson, Professor of Pediatrics at the State University of New York School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. He lists the factors that protect against failure as including

• an early diagnosis of FAS (before six years of age),

• receiving developmental disability services,

• a positive, stable, nurturing home for at least three-quarters of one’s life, and

• not being subjected to violence.80

All of these measures protect against school dropout, jail, and chronic unemployment, says Robinson.81 Kathryn (Kay) Kelly, Project Director of the University of Washington’s FASD Legal Issues Resource Center, agrees.

A Smoking Gun

Tobacco use results in approximately 434,000 deaths and costs the United States $52 billion annually in medical care.82 Most smokers begin in adolescence: eighty to ninety percent of smokers start before the age of twenty. And according to one study, as many as half of Native American adolescents smoke.83 Minority communities are targeted by the makers of tobacco products, a subset of which are cynically marketed to women.

Since the 1920s, women have been targeted by tobacco-marketing strategies promoting “liberated” women, such as Virginia Slims, Silva Thins, and Eve ads, the latter of which are specifically targeted to African American, Hispanic, and Asian women. In 1960, about 10 percent of all cigarette advertisements appeared in women’s magazines: by 1985, this advertising rate had more than tripled.

The reassuring outdoorsy images of fit women engaged in healthy activities like hiking, jogging, and yoga belied the health hazards of smoking. So did the misleading descriptions of the cigarettes’ tar and nicotine content.84 The duplicity did not end with the advertisement: articles in magazines that ran tobacco advertising were much less likely to mention smoking as a risk factor for disease or otherwise criticize the habit than were magazines that did not run such advertising.85

Tobacco companies also wooed racial minority groups by papering urban communities with billboards advertising brands of tobacco and alcohol tailored to the ethnic markets. For example, the cynically named “X” brand, widely believed to refer to Malcolm X, featured a pack that opened from the bottom because company research revealed this as a favored practice of black men.

Tobacco companies also curried favor among African Americans by hiring many black executives at a time when other industries shunned them, and through large donations to cultural groups.86

Smoking rates are higher among African Americans than whites or Hispanic Americans, and this is bad news for their children. Tobacco is known to harm the developing baby in a myriad of ways, including prematurity and low birth weight, which themselves are risk factors for many serious disorders, sudden infant death syndrome, cleft lip/palate, stillbirth, and infant death. Smoking is implicated in other conditions, from heart defects and miscarriage to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.87

This means that smoking cessation is key in protecting the prenatal brain and intelligence.

Accordingly, a 2012 study reassured us that 68 percent of doctors warn their pregnant patients to stop smoking and to avoid secondhand smoke.88

Yet this statistic means that about three of ten doctors offer pregnant woman no such counseling, and these are likely to be women of color. By 2000, both the American Journal of Public Health and the Journal of the National Medical Association had warned that pregnant black and Hispanic women were the least likely to be offered smoking cessation counseling from their physicians.89 But the most recent studies show that doctors most often fail to warn Native American mothers away from tobacco use.

This silence is stunning, especially given the important role of tobacco in many Native American cultures, which may make it harder for women to quit.

Prenatal counseling is an essential source of advice and support for women who seek to give their babies the best start in life. Tragically, women of color sometimes find censure and abuse, not support. Medical counseling and intervention have sometimes been used to vilify women of color, who, beginning in the earliest days of the United States, were blamed for poor birth outcomes by being cast as murderously indifferent mothers. High infant mortality was laid not to the privation and abuse of enslavement and, later, to segregation that separated women of color from care, but rather to “overlaying,” a term doctors used to accuse black mothers of killing infants by rolling over on them as they slept. This diagnosis was reserved for enslaved mothers.

Some still harbor this biased mentality. In Milwaukee, an alderwoman recently pushed to criminalize parents whose babies died after sleeping with them if the parents had been intoxicated.

Centuries after enslavement, the African American infant mortality rate remains high—in fact, it is worse today than it was during enslavement, notes City College journalism professor Linda Villarosa in her brilliant New York Times investigation “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” Current data reveal that American black infants are twice as likely to die as white ones—11.3 per 1,000 black babies, compared with 4.9 for whites.90

As one peruses the medical and social literature that seeks to explain the reasons, a question recurs. Simply stated, it is: “What are black mothers doing wrong?”91

Blame the Victim, Redux: Shades of Guilt

Expectant mothers of color all too often find public condemnation, betrayal, and jail time—or just as dangerously, silence—regarding the risks to their children’s developing brains. The seminal work of Dorothy Roberts, especially her book Killing the Black Body, documents how racism escalates the vulnerability of poor mothers of color, who suffer stricter scrutiny from the legal system and from child-welfare agencies than do their white peers. It has not helped that the current mantra of “personal responsibility” has eclipsed the earlier public health model of corporate responsibility, and this has escalated stigmatization by public health policies.

Today, a kinder, gentler, and far more appropriate medical model dominates discussion of the newly minted “opioid crisis” and other forms of drug abuse. But a harsher legal paradigm has long focused on people of color, with a punitive animus. This punitive approach has leveraged accusations of drug abuse (real or imagined) to constrict minority women’s reproductive freedom—without protecting at-risk children of color.

Take the case of twenty-seven-year-old Darlene Johnson of California, whose judge, Howard Broadman, made her an offer she could not refuse in 1991.92 The African American mother of four had “spanked” her six-year-old daughter with a belt and an electric cord for smoking a cigarette, and her four-year-old got the same punishment when Johnson caught her inserting a wire hanger into an electrical outlet. Now Johnson, who was eight months pregnant, was facing seven years in prison for three counts of felony child abuse. Broadman offered to sentence her to just one year in jail and three years’ probation—but only if she agreed to an implantation of Norplant, a surgically inserted contraceptive that can be removed only by a physician and lasts for five years.

Johnson asked whether it was safe, and Broadman assured her that it was, so she agreed. But when she discovered that Norplant is contraindicated in women like herself who suffer from diabetes and hypertension, she changed her mind. Although the ACLU and even the district attorney (!) joined her lawyers in urging Broadman to release her from the agreement, he would not.

Even Sheldon Segal, the embryologist who developed Norplant, told the New York Times that he was troubled by the medicated device being forced on women. “I just don’t believe in restricting human rights, especially reproductive rights and I’m also bothered because this is a prescription drug, with certain side effects and certain groups of women for whom it may not be appropriate. How does the judge know if the woman is diabetic, or has some other contraindication to the drug?”93

The health concerns were real: Norplant was eventually removed from the market because of serious side effects including stroke, blindness, and permanent sterility.

Like many other jurists who forced Norplant on women of color, Broadman explained that he was acting with the welfare of her children in mind: by preventing Johnson from reproducing, he was ensuring that there would be no more children for her to abuse.

This reasoning is illogical: it does nothing to protect her existing children, as counseling and social-work intervention could. Moreover, preventing a child from being born is a draconian means of protecting it from spankings or abuse. Such rulings are punitive, not corrective.94 There were many Darlene Johnsons: 85 percent of the women on whom the legal system forced Norplant were African American or Hispanic.

Black women have also been jailed for bad birth outcomes, even imaginary ones.

In 1991, we learned that the infamous “crack baby”—always portrayed as black, born addicted, and with profound permanent brain damage caused by the mother’s crack use while pregnant—was a myth. But we learned this only after the headlines blamed neglectful, drug-addled mothers for the “crack baby epidemic,” further stigmatizing black women who sometimes faced legal charges for their babies’ medical issues. As I wrote in Medical Apartheid, the “crack baby” was an imaginary golem created by shoddy, racialized research studies and journalistic sloppiness: in reality, these issues resulted from the various medical risks of poverty and poisoned environments, not maternal drug use.95 After twenty years spent studying crack cocaine, developmental neuroscientist Pat Levitt characterized the near-ubiquitous medical despair over infant golems as “an exaggeration.” “The story that science is now telling rearranges the morality of parenting and poverty, making it harder to blame problem children on problem parents,” Madeline Ostrander wrote in The New Yorker in 2015.96

The mythical crack babies were actually suffering from poverty and its attendant substandard housing, exposure to violence and chaos, overcrowding, and noise, all stressors that can poison the infant brain as surely as drug abuse. Their brain damage is comparable to that of other babies born into poverty.97