CHAPTER 5

Bugs in the System: How Microbes Sap U.S. Intelligence

A young African American mother once asked me if these neglected infections could be responsible for seeing all those little special needs yellow buses in her urban neighborhood every morning during the school year. I responded that she just asked an amazing and profound question, but right now we have not even begun to answer it.

—PETER HOTEZ, M.D., DEAN, NATIONAL SCHOOL OF TROPICAL MEDICINE AT BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE1

A fetus floating languidly in utero and an infant who sleeps seventeen hours a day seem the very definition of indolence. Actually, they are hard at work as they marshal their physical resources to construct a breathtakingly complex brain.

“Being smart is the most expensive thing we do,” writes Christopher Eppig, Ph.D., director of programming for the Chicago Council on Science and Technology. “Not in terms of money, but in a currency that is vital to all living things: energy.”2 Nothing is more expensive, metabolically speaking: brain-building consumes 87 percent of an infant’s energy.

When a fetus or young child is infected by a parasite, bacterium, virus, or other pathogen, fighting the infection is metabolically expensive, too. While at the University of New Mexico, Professor of Evolutionary Biology Randy Thornhill and Eppig found that a child cannot do both. The energy diversion severely taxes the child’s ability to produce a normal brain.

How? The brain of a fetus fighting infection, like that of a fetus exposed to chemical intoxicants (see Chapters 3 and 4), will suffer derangement or malformation that renders it incapable of certain intellectual functions. Missed developmental milestones, struggles in school, or frank learning disabilities and retardation may appear soon after birth, or as late as early adulthood. The New Mexico researchers’ theory of how pathogens lower our IQs by deforming our mental development is called the “parasite-stress theory of intelligence.”

Zika, Our Newest Immigrant

We are all vulnerable to the pathogens that cause this mayhem, but racial and social bias cause them to target poor people of color. These include immigrants from tropical lands but also hundreds of thousands of U.S. natives. Here, as in the developing world, infection by pathogens directly correlates with impaired cognition, memory, concentration, and lower IQ.

The most recent such pathogen to garner headlines is Zika, a virus known to attack neural tissues and sabotage brain development. It was discovered in 1947 among rhesus monkeys in Uganda’s Zika forest, but by 1952 it had moved to humans. The World Health Organization explains that Zika is spread mostly by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, although the virus persists for an unknown period in semen, and sexual transmission from men to women has been documented in the United States and elsewhere.3 In fact, some think that sex has become the chief mode of transmission. Before 2007, Zika was found only in Africa and Asia, but in 2018 approximately fifteen hundred pregnant women contracted Zika, especially in New York City and in the American Southwest, where it is carried by not only Aedes aegypti mosquitoes but also the domestic Aedes albopictus.

In February 2016, the World Health Organization pronounced the burgeoning Zika virus a “public-health emergency of international concern.” Only three other disasters have earned this label: the 2009 H1N1 epidemic, the 2014 Middle Eastern polio resurgence, and the 2014 Ebola epidemic.4

The usual symptoms of Zika disease in adults include mild fever, skin rashes, muscle and joint pain, conjunctivitis, and “malaise” that lasts for two to seven days; fetuses can suffer stillbirth, microcephaly, and eye malformations.5 But unlike the other three disasters, the Zika outbreak threatens more than our physical health: it can also generate or encourage mental and cognitive disorders in affected fetuses.6

When the brains of babies with congenital defects were scanned they were found to be smaller and marked by underdeveloped structures. Complications such as Guillain-Barré syndrome and microcephaly (small heads and underdeveloped brains) in infants have risen with cases of the disease.7

Ominously, a 2015 Brazilian study found that most infants born to infected mothers in that country show abnormal cortices, or outer layers of their brains.

A March 2016 report in the New England Journal of Medicine indicted Zika as a cause of microcephaly after it analyzed the virus’s genome.8 Tatjana Avšič Županc of Slovenia’s University of Ljubljana told New Scientist, “Microscopic examination revealed that brain cells were destroyed due to infection with the virus. While it can’t be definitive proof, it may present the most compelling evidence to date that congenital brain malformations associated with Zika virus infection in pregnancy are a consequence of viral replication in the fetal brain.”9

The infection causes the brain to develop abnormally, which can result in microcephaly, and eighty-five percent of those with microcephaly suffer significant cognitive limitations.10 However, even Zika-infected children who escape microcephaly suffer limitations11 that range from the minor to the significant, including speech delays, seizures, movement and balance problems, short stature, and facial anomalies.12 Experts fear that Zika places “even infants who appear normal at birth… at higher risk for mental illnesses later in life,” according to the New York Times. “The consequences of this go way beyond microcephaly.”13

Conventional wisdom suggests that Zika will not be as disastrous in the United States as it has been in the developing world because of our greater density of health care practitioners and our rich disease-surveillance resources.

But the histories of other neglected tropical diseases that have made landfall in the United States suggest a darker scenario. Like HIV infection and Chagas disease, Zika may come to threaten poor ethnic enclaves of the United States that are subject to the same substandard living conditions, reduced access to health care, and environmental hazards as communities in the global South.

In fact, some scientists compare Zika’s fetal damage to that seen in the children whose mothers were infected with rubella during pregnancy during a 1964–65 epidemic.14 These children were born with deafness, blindness, and mental problems15 ranging from brain swelling to mental retardation. Their brains pay this heavy cognitive price partly because the virus, like other infectious diseases, saps a newborn’s metabolic energy.16 Viruses like Zika also disrupt brain growth by diverting energy from their human hosts to crank out copies of themselves. Other pathogens, like worms and other parasites, infest the digestive tract, where they siphon off nutrients like iron that are necessary to build a healthy brain and nervous system. The results of such nutritional deficiencies include various mental and cognitive deficits from a reduced attention span or memory to lowered verbal intelligence. Lower IQ scores result.17

Moreover, Zika, like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, also causes devastating mental disorders by directly attacking the brains of fetuses or exposing them to attack by the maternal immune system—“friendly fire” that can damage the brain instead of routing the virus, leading to a lifetime of cognitive and mental disability.18

Such brain damage is not as rare as was once thought. Zika’s cognitive damage, for example, was originally reported to be confined to exposures during only one trimester.19 But in March 2016, the New England Journal of Medicine published an ultrasound study revealing that the fetuses of 29 percent of women who had tested positive for the Zika virus were plagued by “grave outcomes.” In vitro experiments show that the virus “targets and destroys” those fetal cells destined to become the brain’s cortex, and fetuses are affected in all three trimesters.20

Guillain-Barré syndrome may also emerge in children affected by Zika, an assortment of alarming and even life-threatening symptoms that come on quickly and are caused by temporary slowing of nerve conduction. In the worst case, this dangerous loss of muscle and nervous system function can stop breathing. Recovery can take anywhere from a few weeks to a few years.21

So Zika is a physical disease and a mental disease that damages the fetal brain, sabotaging cognitive function and with it, intelligence.

Such IQ-pathogen connections can sound like science fiction, but the relationships are scientifically validated and the concept is far from new. As early as 1919, medical researchers in Queensland, Australia, probed the connection between infectious disease and intelligence, and five years later, the Virginia Health Bulletin asked whether its public health system was battling “Stupidity or Hookworm?”22 as it sought to trace the connection between rampant U.S. hookworm infection and abysmal school performance in poor rural schoolchildren.

Hookworm, or Necator americanus, is a parasite that most often works its way into the body from the soles of unshod feet, then migrates to the small intestine where it sucks its host’s blood, causing anemia, weight loss, profound fatigue, and impaired thinking. The rampant hookworm infection of the South has historically targeted the poor who could not afford shoes or decent shelter, and so fed the stereotypes of the stupid, lazy African American and the equally lethargic and slow “redneck.”

But the Virginia Health Bulletin posed its question during the heyday of U.S. eugenics, and the prospect of an infectious, rather than a racial, driver of intelligence ran counter to eugenic theory. The infection theory specifically warred with the common belief that African Americans possess innately low intelligence. The hookworm connection failed to draw funding or the continued attention of researchers and the infestations were widely thought to have dissipated by the 1980s.

Today, however, studies use modern tools to investigate the hookworm-health connection. In Alabama’s Lowndes County, 67 percent—that’s more than two of every three people—are infected by hookworm. Nationwide, the National School of Tropical Medicine estimates that 12 million people are infected.23

We’ve also long known of more widespread diseases that caused sufferers to lose a profound degree of brain function. One such disease is paresis, common in the United States until the 1940s. Affected patients could no longer work, remember basic information, care for themselves, converse with others, navigate independently, or even walk. Eventually they were confined to institutions, then to beds, until the erosion of their brains prevented basic bodily functions and killed them. In the end, paresis was found to be the tertiary and final stage of syphilis infection, so this cognitive devastation was caused by a bacterium.

Paresis is now a foreign disease, but it once was a common diagnosis in early-twentieth-century U.S. asylums. When penicillin was found to cure syphilis, paresis disappeared from the West, and now persists only in the global South and other health care vacuums where people without access to health care still suffer and die from it after losing their memory, speech, emotional stability, and cognition.

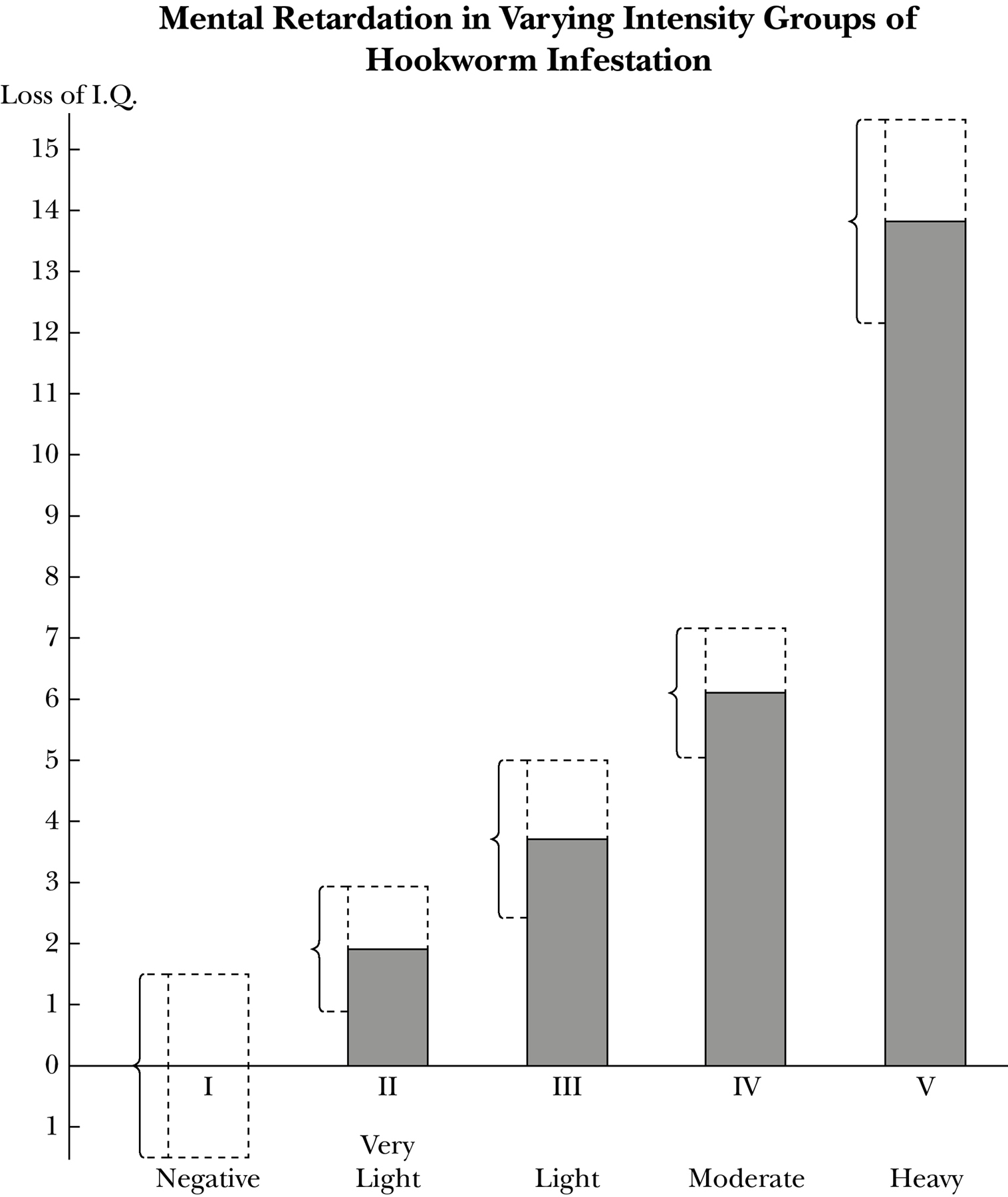

Heavy hookworm infestation correlates with the highest degree (approximately 14 points) of IQ loss; very light infestation correlates with low losses of 1–2 IQ points. Note: Section of bar covered by brackets represents probable error.

In a similar manner, unmasking pathogens that sap intelligence will allow us to staunch the loss of IQ points.

Thanks to the work of scientists like Eppig, Thornhill, and Hotez, new technological knowledge of infection-cognition connections allows us to draw connections, to quantify exposure, and to better understand the mechanisms by which pathogens destroy intelligence.

American Infections

In the United States, paresis is now a disease of the past. In many ways, Zika is a disease of the future in the United States, which has so far avoided the waves of debility that Zika has caused in other, poorer nations. But even if Zika never flourishes here, a plethora of diseases that sabotage intelligence and depress IQ are already with us.24 As Hotez et al. write,

The Big Five diseases—Chagas disease, cysticercosis, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, and trichomoniasis—are quite common here among the poor.… Diseases like schistosomiasis, a parasitic worm infection, hookworm, and Toxocariasis, which strikes the poor in the US—actually reduce intelligence. They reduce IQ among kids, and there are studies to show that when chronic infections occur in childhood [they can] reduce future wage earning by 40 percent.25

These diseases sound unfamiliar, like conditions from elsewhere, and quite recently, even some doctors have denied their presence in the United States. They insist that these neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), as they are still called, only affect the developing world and immigrant enclaves in this country.26

When the patient of a doctor at the Baylor College of Medicine received a letter saying that blood he had donated was being rejected because of a positive test for Chagas disease, the doctor exploded, “The test is wrong. That disease doesn’t exist in the United States!” But it does: at least 330,000 U.S. residents, and maybe as many as one million, suffer from Chagas disease. The Big Five now affect at least 14 million U.S. residents.27

Chillingly, these disorders target poor enclaves of African Americans and Hispanics, sapping the brainpower of poor people of color at home, just as they do abroad.28 Such intellect-sapping diseases target communities in subtropical areas like Houston, Alabama, and Florida. Why?

Because NTDs are not “foreign diseases” anymore. News reports portray Zika as an exceptional tropical disorder, but it is common in one important respect: its appearance in more than twenty American states29 is part of a decades-long pattern. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine, “Dengue hit with a vengeance in the ’90s. Then we had West Nile in 1999, chikungunya* in 2013, and lo and behold, now we have Zika in 2015 and 2016. This is a disturbing, remarkable pattern.”30

After linking high infection rates with lowered IQ, Randy Thornhill and Chris Eppig asked how infection deranges the developing brain and saps intelligence.

In several ways, it seems. Parasites and worms lodged in the intestines siphon off nutrition that the brain needs to develop; “That’s like the next thing after slapping the fork out of your hand. Food gets into your mouth and into your body, but then you can’t absorb those nutrients,” says Eppig.31 As infections sap her energy, the infant’s body must struggle to fight off the invaders and to properly construct her brain with inadequate resources.

But prenatal infections can also damage the brain in horribly versatile ways.

Microbes may breach the linings of our intestinal “second brain,” which contains more neurotransmitters than the brain in our skulls.32 From there, chemical messengers travel to the brain, where they cause excessive and chaotic neuronal firing and damage.33 Of this “leaky gut” model of destruction, Thornhill’s team wrote: “If exposed to diarrheal diseases during their first five years, individuals may experience lifelong detrimental effects to their brain development, and thus intelligence.”34

Or, the brain may be attacked by the baby’s own immature immune system in a florid but inaccurate attempt to destroy the pathogenic invaders, resulting in damage to the brain’s own tissues.

Infectious agents can cause damage to adult brains as well. You may recall that 87 percent of an infant’s energy goes to building a healthy, functioning brain. But a completed adult brain is also high-maintenance, requiring fully 25 percent of an adult’s energy to remain in good working order, and when that energy is siphoned off to fight infection, the brain can be rendered ineffectual and in some cases irreparably damaged.

Mapping Intelligence

Average IQ varies with geography, both across and within nations according to the controversial but widely utilized assessments in IQ and the Wealth of Nations.35 Despite the authors’ notoriously sloppy methodologies, described in Chapter 1, the book purports to rank nations by their IQs and it is constantly recruited to support hereditarian theories.

But other scholars use the book’s rankings as well.

In 2010, Chris Eppig, Corey Fincher, and Randy Thornhill compared data from it and several other IQ rankings to health data from the World Health Organization in order to draw global correlations between a country’s infectious-disease burden and the average national IQ of its inhabitants. The scientists found that the greater the burden of infectious disease, the lower a nation’s average IQ.36

But how robust is this correlation, and what of other variables that might drive intelligence? Nigel Barber, for example, writes that IQ varies in accordance with dramatic educational differences. Donald Templer and Hiroko Arikawa believe that because cold areas are difficult to live in, evolution favors higher IQ in cool climates.

Such factors may contribute to IQ, but what is the most powerful driver of intelligence? Thornhill’s team’s tests corrected for all of the above factors as well as genetics, nutritional levels, national wealth (gross domestic product per capita), average temperature, and for several measures of education. In order to investigate the effects of education on U.S. IQ, for example, Thornhill repeated the analysis across the United States where standardized compulsory education exists.37 In the end, the team wrote, “Infectious disease remains the most powerful predictor of average national IQ when temperature, distance from Africa, gross domestic product per capita and several measures of education are controlled for.”

Geraint Rees, director of the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, told The Guardian that their conclusion appears valid: “It explains about 50 to 60% of the variability in IQ scores and appears to be independent of some other factors such as overall GDP.”38

Eppig’s team concluded that “infectious disease is a primary cause of the global variation in human intelligence.”39

Their analysis didn’t seem to specifically test or correct for environmental poisoning by chemicals or heavy metals like lead, however, so I question whether infectious disease is the most important factor in IQ determination. Nonetheless, their study shows it to be a potent factor.

Further buttressing the importance of infection’s effect on IQ, Eppig points out that it is also a powerful predictor of average state IQ within the United States. High-IQ states include Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont, while California, Louisiana, and Mississippi bring up the rear. The five states with the lowest average IQ share higher levels of infectious disease than the five states with the highest average IQ, and this relationship holds across all of the states in between.40

The next year, Christopher Hassall and Thomas Sherratt of Carleton University repeated the New Mexico study using a more sophisticated statistical analysis. They confirmed that “infectious disease may be the only really important predictor of average national IQ.”41

The parasite-stress theory of intelligence also helps explain why, as mentioned in Chapter 1, nations like Kenya have seen large IQ gains accompany improvements in health status. Just as adding iodine to the diets of 1920s Americans raised the IQs of “dullard” areas by 15 points, the average Kenyan IQ rose 14 points between 1984 and 1998 in parts of the country that enjoyed improvements in health, including reduced disability from untreated infectious disease. Parasite stress explains this, but genetics does not: the IQ gains were too high and too rapid to be explained by evolutionary and genetic mechanisms.

This infection connection also helps to explain similar patterns of IQ elevation, like the “Flynn effect,” in developed nations like the United States (see Chapter 1). These wealthy nations are largely free of the rampant infectious disease found in the developing world, except where pockets of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and other infections plague poorer communities of color.42 In the United States, areas that are plagued by such infection are also areas where people of color live and areas of depressed IQ ratings. Like the Kenyan increase, the Flynn effect in the West can’t be explained genetically.

Neglected tropical diseases most frequently undermine health and cognitive vigor in areas of the United States where conditions resemble those in the developing world. African American children in Baltimore share a life expectancy with those born in Nepal. As the New England Journal of Medicine reported in 1990, black men in Harlem are less likely to live to the age of sixty-five than men in Bangladesh, one of the world’s poorest nations.43 The report added that “similar pockets of high mortality have been described in other U.S. cities.” Such disparities persist.

National averages denoting a welcome decline in mortality rates distract us from the fact that they don’t decline for everyone. Vast differences exist between neighborhoods, and hence between races, within the same area and even within the same city. In 2007, when I lived on 106th Street in a predominately Hispanic area of East Harlem, it had one of the lowest life expectancies in NYC. But ten blocks away, on Ninety-Sixth Street on the Upper East Side, the life expectancy was—and continues to be—the highest in the city. Ten years later, this discrepancy persisted. Fully 650,000 New Yorkers live in communities where the death rate for African Americans under sixty-five is twice the rate for white Americans. Their health mirrors the health of people in the developing world, where infections unknown to wealthy Westerners run rampant. Hotez illustrates one reason why: the environments are similar.

Why, I can take you to areas such as the historical African American wards of Houston such as the fifth ward, or other areas and show you conditions of extreme poverty that closely resemble Recife (in Brazil)—dilapidated housing, no window screens, discarded tires filled with water and organic debris—it looks like the global-health movie we might show to first-year medical students, but it’s Houston.44

As with lead, air pollution, and other toxic exposures, the distribution of infectious disease in America is inextricably linked to the tangled factors of poverty and race. Such intelligence-eroding pathogens do preferentially affect the poor. But within the ranks of the poor, it is racial-minority groups who sicken most often and fare the worst. Texas, home to the nation’s three poorest metropolitan areas and Ground Zero for diseases like Zika and Chagas, has 4.5 million people living below the poverty line, the largest number of any U.S. state. The poverty rates are highest among Hispanics (26 percent) and African Americans (23 percent). Poor Americans are at risk for NTDs, but poor Americans of color are at the highest risk.

Emerging Infections on the Brain

Infectious diseases haunt racial-minority populations. HIV/AIDS, which damages the brains of fetuses and adults alike, is probably the best-known infection that disproportionately affects black and Hispanic communities. We’ve long known that HIV is a disease of poor people of color here, just as it is in Africa. Seventy-one percent of Americans with HIV disease are black or Latino, and 53 percent of the people who died from HIV/AIDS in 2013 were African American. HIV dementia is a well-known example of the damage the virus wreaks when HIV crosses the blood-brain barrier to contribute to various types of neuronal injury.

Less well known are other direct psychological and cognitive costs of HIV infection, which often attacks the brain. The extent of the cognitive damage it causes in children is even more profound. HIV crosses the blood-brain barrier to injure neurons, so HIV-positive children risk a spectrum of brain dysfunction, from encephalopathy to developmental delays.

Nearly nine of every ten U.S. children living with HIV are African American or Hispanic. Infected children in the United States suffer from lower-than-average memory, speed of processing, and verbal comprehension.

Infants who acquire HIV prenatally from their mothers risk developmental brain dysfunction, from encephalopathy to subtle cognitive impairment, language disorders, and developmental delays.45

A 2010 longitudinal study of more than three hundred such HIV-positive children by University of Southern California psychiatrists found that they fell into the low-average scale for memory, speed of processing, and verbal comprehension.46 According to the researchers, neurodevelopmental problems in children and adolescents with HIV might be linked to “changes it provokes in proinflammatory monocytes” of the immune system.

HIV is just one of many brain-damaging neglected infections linked to poverty.47 “12 million Americans suffer from at least one NTD, and many of those 12 million are impoverished African Americans,” Hotez told a House Energy and Commerce committee in 2016.48

Between 2003 and 2005, the poorest areas of Houston were the hardest hit by a mysterious outbreak. Doctors at the Texas Children’s Hospital and the National School of Tropical Medicine discovered that the culprit was the mosquito-borne dengue fever, a virus that had been all but eradicated from the United States by spraying with DDT, a probable human carcinogen, in the 1950s. At the time of the outbreak, dengue fever was regarded as a “foreign” NTD. However, the United States banned DDT in 1972, paving the way for dengue fever’s eventual resurgence here.49

When it reappeared, not one Houston patient was accurately diagnosed with dengue, including the two people who died.50

“Poor whites,” too, have often been referred to as an ethnic group—Appalachians, for example, as discussed in Chapter 1—when it comes to discussion of their inferior intelligence, and they too sometimes suffer disproportionate infection. They also suffer disproportionately from mind-crippling intestinal worms, such as the threadworms (including Strongyloides stercoralis and Ascaris lumbricoides), that cause impaired childhood development around the globe, just as African Americans in some regions suffer from worm infestation.51

African Americans suffer far higher death rates than whites and die an average of four years younger than white Americans do. But poor marginalized whites are slowly losing their lead. In a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences report, David Squires and David Blumenthal write that mortality rates in the United States for white Americans aged twenty-two to fifty-six rose between 1999 and 2014. For thirty years before that, death rates had fallen by 2 percent a year.52 What’s more, Squires and Blumenthal cite suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related liver disease as the drivers of this excess mortality, calling them “despair deaths.”

Books that address these rising death rates (still much lower than that of African Americans) are beginning to appear, but I’ve found almost no contemporary literature that explores relationships between their supposedly lower intelligence and environmental exposure, as I have found for people of color. I suspect there is a link, but the data vacuum in this area prevents me from discussing it as I had hoped.

The prevalence of pathogens and infectious diseases found among pockets of racial minorities contributes to these disease vectors’ invisibility in the United States. So does a comforting public health narrative claiming that the United States is protected by disease surveillance and environmental measures. We have confidence in the ability of the wealthy United States, with its rich matrix of health care and clean, climate-controlled environments, to ward off NTDs in a manner that the tropical world cannot.

Periodic trash removal, environmental regulations, and prevalent air-conditioning are common here and discourage the breeding conditions for mosquitoes and other disease vectors.

However, such measures are often insufficient or absent in neighborhoods of color. Laws that maintain safe environments are inadequate, unenforced, or simply don’t exist.

This is especially apparent in the nation’s poorest major metropolitan area, McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, Texas, which is situated near America’s eight poorest smaller cities, all of which are marred by poor sanitation, environmental contaminants, and overcrowded substandard housing. These are home to ethnic enclaves of African Americans and other minority-group members. They are also located in the warmest part of the nation, which adds to the risk of infection for the poor people of color who live there.

We see the same institutional failures around the country, including in African American enclaves of Houston, where Robert Bullard, the author of Dumping in Dixie, has documented how sanitary services and even basic utilities are often missing from African American communities, and not just the poor ones. Even middle-class African American neighborhoods sometimes lack basic utilities and adequate sanitary services.

We’re not talking just about rural backwaters but also of thronged urban sites, which is significant because many infectious illnesses thrive and gain virulence in the sort of overcrowded conditions so commonly found in cities.53 This environmental neglect of poor communities of color has laid out the welcome mat for infectious diseases. Dilapidated housing infested with triatomine bugs that carry Chagas disease, rodents carrying hantaviruses, cockroaches that have been shown to worsen asthma, desultory garbage collection and disposal, water and microbes that collect in run-down air conditioners, to say nothing of old tires that provide breeding grounds for mosquitoes, foment infectious disease in the United States, just as they do in Haiti, South African townships, and Brazil.54 In this sense, the oft-invoked distinction between diseases that threaten the developing world and those of the developed world has eroded.

Chagas disease is borne by an unwelcome immigrant—the triatomine or “kissing” bug, which lives in the cracks of substandard housing and passes on the parasite to people by defecating while sucking their blood. When the victim scratches the affected area he transfers the pathogen-laden fecal matter into the tiny bite wound triggering a chronic, silent parasitic infection that can lead to fatal heart or intestinal damage in two of every five sufferers. It also causes intellectual retardation in as many as one in ten sufferers.55 Chagas mainly affects Hispanic communities.56

Cysticercosis

Cysticercosis causes epileptic seizures and other brain damage in a process as gruesome as any horror film.

Beginning in 2008, lurid national headlines screamed, “The Worms That Invade Your Brain,” “Worm Removed from Woman’s Brain,” and “Hidden Epidemic: Tapeworms Living Inside People’s Brains.” MRIs of patients who presented to emergency rooms with sudden epilepsy or fainting began to reveal that their brains were irregularly studded with tapeworms.

That’s right, tapeworms. Although we think of them, when we must, as infesting the human digestive system, where well-nourished specimens can grow to twenty feet or more, these tapeworms result from a parasitic infection known as taeniasis.

Each tapeworm produces a wealth of 50,000 eggs, which are shed in the feces of infected people. Once on the ground and eaten by pigs, they grow into larvae that normally burrow into porcine blood vessels where they wait to be consumed by humans eating undercooked pork, and their life cycle begins again.

But sometimes the eggs from the body of an infected person take a fateful detour when accidentally ingested by another human instead of a pig. When the infected person prepares food without washing his hands, for example, an egg develops into a larva that burrows into the human bloodstream and hitches a ride to the brain. Tunneling into the brain, these larvae become encysted, cloaking themselves from the immune system with specialized tissues. Thus ensconced and unmolested by the immune system, they unleash the horribly versatile disease called cysticercosis.

Cysts near the brain’s visual cortex can blind the carrier. Cysts near the language area can disrupt speech or its comprehension. Cysts sometimes block the flow of cerebral fluid, causing hydrocephalus, which necessitates a shunt to relieve the pressure and prevent unconsciousness. Blindness, epilepsy, and lowered mental function (which means lowered IQ) are common, and so is death.

Treatment may not save the intellect because although the drug praziquantel kills the larvae, it also unleashes a vigorous immune response—“friendly fire”—that ends up harming the brain.

Cases are more common than one might think. In 2012 Ted Nash, chief of the gastrointestinal parasites section at the National Institutes of Health, told Discover magazine, “Minimally, there are 5 million cases of epilepsy [worldwide] from neurocysticercosis.” Between 1,500 and 2,000 neurocysticercosis cases are diagnosed in the United States57 every year when confused, unconscious, or epileptic patients are brought to the hospital and the detection of antibodies definitively identifies the disease.58

Most cases are found in Hispanic Americans, who are more likely to ingest pork-borne tapeworm eggs. A 2012 Public Library of Science (PLOS) report reads, “It is now well established that cysticercosis is a leading cause of epilepsy among Hispanics living in Texas, with Texas and California most likely representing the greatest share of the 169,000 cases of cysticercosis in the U.S.”59

As with many such worm-borne pathogens, deworming arrests the cognitive decline, but it does not restore lost intellectual functioning. Today, one of every ten people brought to Los Angeles hospitals with an epileptic seizure suffers from neurocysticercosis. This is only one dramatic manifestation of an epidemiological sea change: tropical diseases—and their neglect—are not limited to the tropics anymore.60

Toxocariasis

Toxocariasis is caused by Toxocara canis, a parasitic roundworm that infects dogs. People can acquire it from soil and sandboxes contaminated with dog feces.61 The larval worms navigate through the lungs and brains of children to cause pulmonary dysfunction and wheezing akin to symptoms caused by asthma, but they also cause cognitive and intellectual deficits.62 Toxocariasis slipped over the border to infest poor, run-down urban areas and crumbling rural homes in the American South.63 Toxocara canis is now carried by 21 percent (more than one in five) of African Americans, for a total of 2.8 million people.64 “The fact that it may affect the mental health of so many black children has prompted me to speculate that toxocariasis might be responsible for educational achievement gaps during preschool and the school-aged years,” Hotez said in 2013.

That year, his speculation was validated by the heavily detailed annual U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which used the Wechsler Intelligence Scale and the Wide Range Achievement Test to compare the mental acumen of children aged six to sixteen who were infected with Toxocara canis with that of uninfected children. It found that children without the infection scored considerably higher on both intelligence-test scales, even after correcting for a laundry list of potentially confounding factors, like “socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, rural residence, cytomegalovirus infection, and blood levels of lead, all of which have been implicated in affecting intelligence test scores.”65

African Americans and Hispanics also have the nation’s highest rates of death from Toxoplasma gondii infection, which causes the disease toxoplasmosis and a slew of other medical problems.66 This parasite of cats can result in fetal death and abortion as well as psychiatric syndromes that include neurocognitive deficits and even schizophrenia, according to Robert Yolken, director of developmental neurovirology at Johns Hopkins University.67

Trichomoniasis

An estimated 3.7 million people in the United States suffer from Trichomoniasis vaginalis, a parasitic infection that causes the nation’s most common curable STD. “Trich” is a largely silent infection; fewer than one in three infected people notice symptoms. But it can cause fetal death and damage, including neuronal damage that cripples intelligence, and its rate is ten times higher among black women than others. Twenty-nine percent of African American women carry T. vaginalis, not too far from the 38 percent of infected women in Nigeria. This means that black women are ten times as likely as white or Hispanic women to harbor the parasite, which increases the heterosexual spread of HIV. Highly sensitive diagnostic tests can now detect T. vaginalis, and it can be easily cured with a single dose of metronidazole. Unfortunately, neither the test nor the treatment is routinely administered.68

Fortunately, most people infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) never know it, because it rarely causes serious symptoms or problems in healthy people with functional immune systems. But a pregnant woman who develops an active CMV infection can pass the virus to her baby, and one in five infected babies suffer impaired nervous system development, leading to hearing and vision loss that may become severe and permanent, as well as mental disabilities. If the infection is diagnosed at birth, medications called antivirals can be given, which can alleviate the visual and hearing loss.69

CMV infects more African American women than mothers of any other race.70 Infected adults often have no symptoms, except for those with compromised immune systems who can experience symptoms and even die.71 A myriad of other infections like malaria, cerebral tuberculosis (which targets the brain), hookworm, trachoma, and leishmaniasis preferentially impair the brains of ethnic minority groups in the United States.72

Climate of Fear

But why have NTDs gained a foothold in the United States? Xenophobes may accuse immigrants of bringing these transplanted nightmares north with them, but this is inaccurate: many NTDs are infectious, but not contagious. This means that they are transmitted to others by pathogens, but not by infected people.

Instead, blame the U.S. climate,73 because many microbes function within a narrow temperature range, and parasite life cycles often require heat. “The U.S. is somewhat unusual in being a wealthy nation much of whose population lives in very warm, humid regions,” Stan Cox, a senior scientist at the Land Institute, told the Washington Post in July 2015.74 U.S. temperatures are warmer than those in Europe and most of the affluent West.

Accordingly, scientists predict that global warming will hasten the spread of pathogens and disease. As the climate grows even warmer, microbes and disease vectors, such as the snails that carry schistosomiasis, the sandflies that carry leishmaniasis, and triatomine bugs, will expand their territory, and so will the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that disseminate Zika, dengue fever, chikungunya, and yellow fever.75 These are already common on the Gulf Coast, as is the domestic Zika vector Aedes albopictus, which is found in the eastern United States.76

Meteorological events also escalate the risks of infectious diseases that threaten intelligence. In 2005, the “kissing bugs” that carry Chagas disease and the snail populations that cause schistosomiasis proliferated in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,77 and we can expect similar spikes after each hurricane season.

But humans cause problems after weather emergencies, too. Three Caribbean-U.S. hurricanes, two severe Mexican earthquakes, and waves of flooding across Bangladesh, Nepal, and India made the autumn of 2017 meteorologically memorable. Rebuilding will take years, and unfortunately post-disaster construction has a way of disproportionately worsening environmental conditions for the marginalized people in affected areas,78 as debris is dumped in their neighborhoods.

Rebuilding often uses toxic materials as well. In post-Katrina New Orleans, for example, environmental and air-pollution standards were relaxed to accelerate reconstruction. What’s more, as part of post-Katrina recovery efforts, private companies were allowed to acquire public housing. The homes of poor evacuees were condemned as nuisances, marked for demolition, and resold at extremely cheap prices. Such actions, along with the billions allocated to the Army Corps of Engineers for rehabilitation of levees, entrenched, rather than eased, the vulnerability of poor communities of color, both by introducing additional environmental exposures in the short term and by displacing former residents from the safer, rehabilitated housing in the long term.

What happened in New Orleans is reminiscent of San Francisco’s attempt to move Chinatown from the city center to a more peripheral area on the city’s outskirts, ostensibly as part of its rebuilding efforts after the 1906 earthquake.

A 2017 Nature article by Benjamin K. Sovacool points out that Hurricane Harvey hit hardest in poor areas and minority communities located near the Arkema chemical plant in Crosby, Texas, which exploded after the storm.79

Even in the absence of floods and hurricanes, U.S. Geological Survey scientists warn that the armies of pathogens on the ground enjoy ample air support as “hazardous bacteria and fungi hitchhike across the Atlantic on [15,000-foot-high] winds, eventually scattering the pathogens of the developing world over American yards and playgrounds.”80 (You can see this for yourself by searching “North African dust plumes” at https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov.)81

New Domestic Threats

Not all emerging diseases in the United States hail from Africa or the global South. Some are homegrown.

In October 2014 a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences report describes how Johns Hopkins professor of medicine Robert Yolken was surprised to find a waterborne virus called Acanthocystis turfacea chlorella virus—mercifully nicknamed ATCV-1—lurking in the throats of two of every five of his Baltimore research subjects.82

The cognitive tests conducted as part of his study delivered an even greater shock. When the performance of the infected was compared to that of those who did not harbor the virus, researchers found that the infected made calculations 10 percent more slowly and displayed shorter attention spans, suggesting that the virus may retard the ability to calculate and to process visual information.83 This reduced mental functioning occurred independent of potentially confounding factors like age, socioeconomic status, education, place of birth, and smoking status. Gender and race made no difference. No demographic data allow us to stratify this threat by race, but Baltimore is 65 percent African American.

Yolken’s findings persisted when this small study was repeated in a larger population. This correlation strongly suggests an intellect-lowering role for ATCV-1 in humans, but a potentially definitive study was not conducted: the scientists did not expose healthy people to the virus in order to compare their performance pre-and post-infection for obvious ethical reasons.

However, the team did test a group of mice before and after exposing them to ATCV-1, and found 1,000 gene changes in brain regions that are integral to memory and learning. The infected mice also wore dunce caps, taking 10 percent longer to navigate a maze than uninfected controls, and they spent 20 percent less time investigating novel environments, which suggests a reduced attention span. Critics suggested that the researchers had found not an IQ-lowering microbe but rather sample contamination, but Yolken refuted this suggestion in an article in the February 2015 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.84

Red Tide

Other pathogens endemic to North America are known to diminish mental function. When I worked in a poison control center during the 1980s, we kept track of warnings of “red tide” algae that periodically bloom during warm weather. We used the information to warn worried callers and emergency-room physicians of this occasional threat and also urged newspapers to advise their readers. Shellfish toxins sicken 60,000 every year, and kill nine hundred,85 but only after I looked up a new disorder associated with the algae—“amnesiac shellfish poisoning”—did I understand how cruel and unusual red-tide poisoning could be.

In 1987, 107 Canadians fell victim to amnesiac shellfish poisoning after consuming tainted mussels from the waters off Prince Edward Island (PEI).

Eating seafood tainted by Pseudo-nitzschia algae triggers much more than the usual mayhem of nausea, intestinal pain, projectile vomiting, and explosive diarrhea. For the PEI diners, these unpleasant effects were eclipsed by horrifying cognitive symptoms. Thanks to domoic acid, a potent neurotoxin contained in Pseudo-nitzschia algae, the infected became confused, aggressive, disoriented, and prone to endless crying jags. They also permanently lost the ability to form any new memories.86

This toxin is a neural imposter that resembles the essential amino acid glutamate so closely that our brains cannot discern the difference. When taken up through the blood-brain barrier, it kills neurons in the hippocampus, the seat of memory, and in the amygdala, which mediates fear and anxiety, generating prolonged crying that is sometimes followed by coma and death. Four of the PEI victims died, and in the spring of 1991, domoic acid was also measured in razor clams collected on Washington State beaches. Pseudo-nitzschia has been identified in seven algal species and has spread to contaminate shellfish in Japan, Denmark, Spain, Scotland, Korea, and New Zealand.87 Other toxic algae, like Pfiesteria piscicida, also induce mental deficiencies, such as memory loss.

Pseudo-nitzschia red tides have recurred with increasing frequency, and scientists predict that climate change will trigger even more frequent occurrences. No data suggest that people of color are more likely than others to come into contact with these brain-eroding algae. Instead these appear to be a small and localized, but growing source of potential intellectual deterioration for everyone, and another argument for the EPA to acknowledge and counter climate change.

Mad Cow and More

And then there are prions, infectious proteins first identified by Stanley Prusiner, who won the Nobel Prize in 1997 for his discovery. These cause bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), better known as mad cow disease, and its analogous human diseases. The latter include kuru, discovered decades ago among the New Guinea Highlanders, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD),88 a rapidly progressive, fatal disorder marked by profound mental deterioration. Its symptoms include impaired memory, loss of mental acuity, dementia, and impaired muscle control.

CJD killed legendary choreographer George Balanchine—after being initially misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease when he could no longer remember dance moves and musical scores or maintain his balance long enough to demonstrate new choreography. According to the NIH, CJD strikes only three hundred U.S. residents each year, but Laura Manuelidis, chief of neuropathology at Yale Medical School, has theorized that many cases of supposed Alzheimer’s, which can be definitively diagnosed only upon autopsy, are misdiagnosed CJD, just as Balanchine’s was. Because African Americans are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s twice as often as whites, scientific scrutiny into this possibility could be a great boon to the community because at least some cases of CJD, unlike Alzheimer’s, can be prevented by removing suspect meats and proteins from the diet.

Psuedo-nitzschia, the ATCV-1 chlorovirus, and prion disease are obscure hazards, but another domestic malady, Lyme disease, is familiar, and so are the cognitive deficits some infected people suffer.

A lesser-known tick-borne disease, Powassan virus (POW), causes fever, vomiting, seizures, and memory loss, and about half of its survivors are left with permanent neurological symptoms. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10 percent of all cases are fatal.89 Symptoms usually show up about a week to a month after the tick bite. No vaccines or medications are available to treat or prevent the virus infection, so the best way to protect yourself is to avoid contact with wooded areas that may harbor ticks, and to apply DEET repellents. A 2018 Consumer Reports survey found that only one in three Americans thinks that DEET is safe, but since 1960, 90 percent of reported problems were mild and only one in every million users has experienced a seizure or serious medical problem. Most of the latter occurred when people misused the product, failing to follow the package directions. The EPA does not classify it as a carcinogen, nor have CDC studies of adults and children found health hazards.

Still, experts advise not using DEET around children younger than two months of age, and pregnant women should avoid it out of an abundance of caution, although no study has demonstrated any effects of small exposures on unborn children.90

We must remember that exposure to microbes doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The communities that are most susceptible to infection are those that also suffer onslaught by poisonous heavy metals, toxic chemicals, and other agents whose devastating effects on fetal and adult brains have been demonstrated. The effects are additive and perhaps even synergistic, rendering existing calculations about the relative contribution of microbial infection to intelligence simplistic.

The collective freight of these exposures conspires to drag down the intelligence of ethnic minorities.

Mind-Boosting Microbes?

One potential answer to the destruction wrought by infection is still speculative, to be confirmed by future researchers—if it is ever confirmed at all. Although it remains under investigation, it is too intriguing to ignore.

We know that some microbes erode intelligence, so perhaps there are microbes that enhance it. A pair of immunologists think that they have found one.

In the 1990s, John Stanford and Graham Rook patrolled the shores of Lake Kyoga in Uganda seeking the answer to a puzzle: local residents had responded much better than others to the BCG tuberculosis vaccine, and they wanted to know why. They found the answer in the soil of the lake bed: Mycobacteriam vaccae, a bacterium with immune-modulating qualities that make the vaccine more potent.91

M. vaccae has proved versatile. Injecting it into mice raised their serotonin levels and decreased their anxiety. The investigators wondered whether it might affect learning, so they fed the bacteria to mice and then tested how well they navigated a maze. The bacteria-fed mice raced through the maze twice as quickly as the controls.

Another scientist tested M. vaccae in humans in an attempt to prolong the lives of lung cancer patients: it did not prolong their lives, but it tamed their anxiety and raised their spirits. Recently, Environmental Health and Technology published a study of twelve hundred people showing that M. vaccae might significantly enhance learning ability.92

Vinpocetine is another brain-boosting candidate, a synthetic compound that is derived from vincamine, an alkaloid found in the Vinca minor L. plant.

It has been used clinically in many countries for more than thirty years to treat cerebrovascular disorders such as stroke and dementia93 by clinicians who think it improves brain function.

Dr. Akindele Olubunmi Ogunrin, a neurology researcher at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital in Benin City, Nigeria, studied the efficacy of vinpocetine (trademark name Cognitol) in improving memory and concentration in cognitively impaired patients. He found that vinpocetine was in fact effective in improving memory and concentration in patients with epilepsy and dementia, although its efficacy was minimal in demented patients.94

According to WebMD, “Vinpocetine might have a small effect on the decline of thinking skills due to various causes,” and no significant harmful effects were reported in a study of people with Alzheimer’s disease who were treated with large doses of vinpocetine (60 mg per day) for one year.

Vinpocetine is sold by prescription in Germany under the brand name Cavinton, and it is already on sale as a dietary supplement in the United States under various names.95 But I’d advise you to save your money. Although website advertisements claim that “more than a hundred” safety and effectiveness studies have been funded by the Hungarian manufacturer Gedeon Richter, few double-blind controlled clinical studies have been published. And of these, “Most… were published prior to 1990, and results are hard to interpret because they used a variety of terms and criteria for cognitive decline and dementia.” So for now, the prospect of using a microbe to enhance IQ instead of diminish it remains an intriguing but unanswered question.

What, then, can be done to prevent the damage inflicted by microbes or to mitigate the effects of poisonous air, water, metals, food, and chemicals? In the next chapter I suggest solutions for you, your family, and your community that offer hope for maximizing the intellect of our nation.