After the defeat of Huerta, the Constitutionalist forces loyal to Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón moved quickly to recruit urban labor support against their provincial rivals led by Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata. The active diplomacy of Obregón became the most effective link between the Constitutionalists and the organized working class.

The Treaty of Teoloyucan, signed on August 15,1914, formally transferred political authority to the Constitutionalists and permitted the peaceful entry of Obregón’s troops into Mexico City. Because of Huerta’s closure of

Emancipación Obrera and Casa headquarters, the Lucha leadership group regarded the arrival of the Constitutionalists as the “liberation” of Mexico City and hailed the Constitutionalists, some of them quite radical, as the “liberators.” On August 20, the date of Carranza’s triumphal entry, Lucha leaders held a “liberation celebration” at Casa headquarters. The new government sent a sizable contingent of representatives noted for their prolabor sympathies to the ceremony, including ex-Magonista Antonio I. Villareal. The assembled Casa members and their guests then heard a series of discourses on “proletarian revolution” and anarchosyndicalism delivered by Roldán, Huitrón, de la Vega, de la Colina, and others. The government delegates did not appear intimidated by the radical rhetoric of the Casa leadership and assured the assembled workers of the social nature of the Constitutionalist revolution and that the desperately poor living conditions and food shortages experienced by the urban workers were the primary concerns of the new government. They called for working-class support for the “Revolutionary Government” which they claimed acted on organized labor’s behalf.

1On September 26, Obregón followed up these initial contacts with the Casa by donating to it the building of the former Jesuit convent of Santa Brígida as a meeting place. The Casa accepted the gift, and in less than five weeks the urban labor leaders seriously compromised their ideological pledges of nonpolitical involvement. The close working relationship established by Obregón with the Casa, the unusual political conditions that prevailed, and an openly sympathetic government overruled allegiance to an unmodified anarchosyndicalism. Cooperation with Obregón, under what they believed to be their own terms and exercized in their own interests, seemed advantageous to both rank-and-file members and a majority of the Casa leadership.

In the fervor of “liberation,” anarchosyndicalist leaders who later disavowed the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM), because of “government domination,” accepted Obregón’s gift, apparently without dissent. Because of difficult conditions, anarchists considered the acceptance of such donations from a supportive government to be wise and not necessarily compromising.

2 From the Constitutionalist government’s point of view, urban labor constituted a sizable and potentially powerful force. The donations cost the government little and they helped create good will among urban workers.

The reopening of the Casa in late August 1914 precipitated an intense organizing campaign in which Lucha representatives visited factories and artisan shops in Mexico City, Guadalajara, Monterrey, and the other principal centers of industry nationwide. The basis for the reconstruction of the Casa was prepared during its months of banishment under Huerta by means of an underground system of committees and emissaries sent out from Mexico City to cities all over the central Mexican plateau, including the states of Puebla, Michoacán, Hidalgo, Guanajuato, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí.

During the last months of 1914, anarchists formed regional

casas del obrero in Guadalajara and Monterrey and these branches sent emissaries to the central Casa in Mexico City. The Monterrey Casa included the local syndicates of painters, carpenters, stonecutters, confectionery workers, drivers and conductors (

motoristas y conductores), bakers, smelter workers, tailors, matchmakers, textile workers, and electrical railway workers. The Monterrey Casa organizers included Vicente Aldana, Carlos García, José Spagnoli, F. Rivera, and G. Cervantes Lozano. They began publication of their own newspaper,

Ideas, in November, stating “… our ultimate desire is the happiness of all, without gods, capital, or tyrants.” Anarchosyndicalism, they believed, would achieve “victory” in the Mexican Revolution and, among other things, bring about the emancipation of women and the defeat of “fanaticism.” The syndicates in secondary population and industrial centers, such as San Luis Potosí and Aguascalientes, were less powerful and ambitious. Originally stimulated by the visits of Casa proselytizers, including Celestino Gasca and Rosendo Salazar, they joined the Mexico City Casa.

3The Casa moved toward a more refined and elaborate national structure composed of affiliated syndicates. The syndicates operated as autonomous nationwide groups affiliated with the Mexico City Casa at the national level and a local Casa del Obrero in those towns where the syndicate locals organized. At both the national and the local level the syndicate remained “self governing.” Any action taken in concert with the national Casa occurred at the syndicates’ and regional

casas’ discretion. They affiliated with the national Casa for armed defense through local workers’ militias and armories. However, this design existed largely in theory because of minimal coordination of the self-defense committees and the isolation of many syndicates. Thus, Casa social services—such as general nutritional aid and hygenic education, organizing assistance and ideological direction, and cooperation and coordination of syndicates during strikes—only partially developed and functioned most effectively in the larger cities.

The leadership of the national syndicates integrated with the national directorate of the Casa in Mexico City and increased the total number of Casa directors to more than seventy-five. As the directorate of the national Casa grew, the former Lucha leadership group increased in number until it became so large that Lucha disappeared as a separate entity. In the late months of 1914 the rubric “Lucha” fell into disuse. Casa growth required an increasingly complicated organizational structure. Eventually, Casa activities were conducted by twenty-three committees run by unpaid secretaries who held membership in the national directorate.

The more important national urban working-class and artisan groups which joined the Mexico City Casa as syndicates included the tailors (sastres), restaurant workers (Sindicato de Dependientes de Restaurantes), weavers, stonecutters, textile factory workers, carriage drivers, mill workers, chauffeurs, shoe factory workers, mechanics, blacksmiths, school teachers, plumbers, tinsmiths, beltmakers, button-makers, retail clerks, bakers, models, draftsmen, seamstresses, and bookbinders. The Casa was a mixture of the middle and lower economic strata of the employed work force. The Tipógrafos remained the single most influential syndicate in the Casa, and they increased their strength through the assimilation of the linotypists’ union. The new syndicate styled itself the Sindicato de Tipógrafos y Gremios Anexos. Jacinto Huitrón, a linotypist, served as the Casa delegate to the Anarchist International Conference in 1914.

Beginning in late 1914, rapid unionization, the continuing turmoil and instability of the revolution, extreme inflation, and high urban unemployment rates contributed to labor unrest and led to strikes in the major cities. Serious strikes closed down the Mexico City rail transit system, the electrical company, and the telephone and telegraph company. The syndicates involved, all affiliates of the Casa, had developed a strong sense of workers’ unity and, because of the crucial public service nature of their industries, they possessed unusual strength. The Carranza government found a solution for the power company strikes by giving the union a partial management role in order to restore service. One new leader, Luis N. Morones of the electrical workers’ syndicate, suddenly emerged with enormous influence. The Casa leadership applauded these developments because to them they represented workers’ control of industry. But Morones did not embrace anarchosyndicalism and began to discreetly develop a close working relationship with the government. He established friendships with many high-ranking government officials and, without alienating Lucha veterans, subtly prepared the way for his future rise to power.

4The leaders of the new syndicates also included some Casa veterans, such as Celestino Gasca and Spanish anarchist Juan Tudó. The newcomers cooperated with and supported the Lucha old guard and the principal of no political compromise in the Casa directorate. However, despite their declarations of anarchist ideology, in late 1914 and early 1915 the new leaders reinforced the resolve of Quintero, Salazar, Gasca, and the rest of the leadership as they led the Casa into closer “revolutionary unity” with the Carranza-led Constitutionalists against Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata. In addition, less militant new leaders, such as Leobardo Castro and Samuel Yudico, moderated and openly supported Morones after 1916 as he led organized labor into a position subordinate to the Carranza, Obregón, and Calles governments.

5Due to the complexity of events in Mexico, interpretations of their significance varied widely and led to disputes between the participants in Mexico City and the anarchist Flores Magonistas residing in Los Angeles, California. The latter attached greater immediate significance to the fall of the Huerta government and the growth of the Casa than did the Mexican urban working-class leaders themselves. Casa writers sometimes violently rejected the tactically more radical Magonistas and their revolutionary claims. In one case, a writer described them as “renegades thousands of miles away who are exaggerating events in Mexico” and asked, “How can it be expected that Mexican workers could be carrying out the social revolution [as the Magonistas claimed], if they were not yet even organized or politicized? How could Mexican workers be expected to achieve this if it had not yet been possible in Europe where the workers were much more advanced?”

6 The Casa leadership’s evident hostility toward the PLM intelligentsia in exile prevented official contact between them.

Despite their scorn for the revolutionary predictions of the far-removed Magonistas, a growing sense of urgency drove the Casa directorate on in its rush to organize and ideologically indoctrinate a maximum number of workers as quickly as possible. In order to facilitate this effort, the Casa published another newspaper,

Tinta Roja, as a replacement for the Huerta-suppressed

Emancipación Obrera. Salazar, Arce, and de la Colina edited

Tinta Roja. The exclamation “there is no time to lose”

7 explained the situation. A dual program of teaching anarchosyndicalist ideology to the workers while seeking cooperation with the lenient Constitutionalist government emerged. The Casa therefore temporarily discouraged strikes, despite difficult economic conditions and employer refusals to raise wages, because of its desire to avoid alienating the tolerant Constitutionalists. Strikes called in search of short-run benefits were condemned as long-run errors. The Casa moved quickly to organize as many workers as possible while impressing the government with the need for urban working-class support in the face of Villa’s superior military strength. Many of the Casa directorate realized that the bulk of the organizing had to be achieved while the Carranza regime still regarded the urban workers as useful allies.

Most of the Casa leadership still distrusted government in general and Carranza in particular but displayed an increasing willingness to cooperate. The eventual alliance between the Casa and the Constitutionalists stemmed from the government’s aggressive courtship of the urban workers, the desire of the Casa directorate to organize the workers quickly while the Constitutionalists still needed them, the important losses due to exile and repression which the old Lucha leadership had suffered at the hands of the Madero and Huerta governments, and the departure of the minority agrarista Lucha leaders from Mexico City in the early months of the struggle against Huerta to take up arms for Zapata in Morelos or the Constitutionalists in the north.

The Casa was already deeply indebted to the Carranza movement before the advance of Villa’s forces in late 1914 forced the Constitutionalists to withdraw from Mexico City. The relationship began when Carranza’s Constitutionalists occupied Mexico City and the Casa reopened, admitting many new members grateful to and sympathetic with the Constitutionalist cause. These men viewed the Carranza-led movement as friendly to labor and believed less tenaciously in the anarchist antigovernment ideas of no political participation than did the old membership. The radical Casa leadership hoped to mold the workers into a formidable anarchosyndicalist force prior to an inevitable conflict with Carranza. Meanwhile, Obregón carried out an aggressive courtship of organized labor among both non-Casa-affiliated workers and the Casa itself. The government took a giant step toward gaining greater short-run rapport with the Casa through its decision to issue paper notes in place of five-, ten-, and twenty-centavo coins then in short supply.

8 The measure provided considerable relief to the most desperately poor of Mexico City’s working class.

In one major labor contract agreed upon in late 1914, the government served as arbitrator between Puebla textile workers and management. The workers received the eight-hour day as a result. Similar gains occurred in the Federal District and impressed even members of the Lucha old guard. Against the aura of Constitutionalist radicalism, the immediate sense of good will with the Casa created by the Carrancistas, and the conciliatory diplomacy of Obregón, the Villa northerners and Zapata-led agrarians seemed very remote to most Casa members.

9The absence of many Lucha

agraristas also contributed to the Casa’s ultimate decision to join the Constitutionalists. The agrarian-oriented leadership of the Casa for the most part had left Mexico City prior to the time the Constitutionalist recruiting effort headed by Obregón got under way. Severiano Serna and Joaquín Hernández traveled to Puebla and attempted to foster “resistance societies” against Huerta there, only to be apprehended and executed. During Huerta’s reign, Anastasio Marín, the Flores brothers, Enzaldo Díaz, Eleuterio Palos, Eliás Tinajero, and Díaz Soto y Gama joined Zapata in the south and what they regarded as an indigenous liberation movement in support of the

municipio libre. In late 1914, Luis Méndez joined Zapata. Jacinto Huitrón also became an avid agrarian and worked in a Zapatista electrical plant. Some radical Lucha members—Eloy Armenia, Colado, and Roldán—joined the Constitutionalist movement much earlier. They enrolled in and helped to organize a miners’ militia in Coahuila in 1913.

Between November 2 and 24, as the forces of Villa and Zapata advanced on Mexico City, the Constitutionalists withdrew toward Cordoba and invited the Casa to declare its support. At first the leadership of the Casa, surveying the situation, declined to transmit this request to the general membership or to the affiliated regional syndicates. But on the twenty-fourth the Zapatistas entered the city and the Casa directors witnessed what they considered a pitiful spectacle as the Zapatista troops humbly begged tortillas on the doorsteps of “bourgeois homes.” The Casa leaders also objected to the ceremonial meeting of Zapata and Villa at the National Palace. They complained that the leader of the northerners acted suspiciously like a “personalist.”

10Cultural and economic factors also played an important part in the ultimate decision by the Casa to reject Zapata and Villa in favor of the Constitutionalists. Urban workers, like their colonial-period and nineteenth-century ancestors, considered themselves citizens of Mexico City and much more sophisticated and modern than the

campesinaje. As constituents of Mexico City, they enjoyed the way of life and the general wealth of the metropolis even if an unbalanced distribution of income gave them only peripheral advantages, such as public transportation and parks, sewage disposal, and other public services. The Casa found the religious devotion of the Zapatista revolutionaries and their acceptance of the clergy particularly aggravating. Religious arm patches and banners, such as the Zapatista Virgin of Guadalupe, especially galled the Casa “rationalists.”

11 Villa’s personal habits soon earned him the label of “villain,” and rumored church support of his cause lent to the rubric “the reaction.” These impressions were gross simplifications and unfair caricatures, but in the minds of the Casa leadership the agrarians and the Villistas seemed to represent

“la reacción,” the cultural values of a bygone age.

By January 1915 the sentiment that Villa and Zapata were enemies had taken hold of most of the anarchosyndicalists’ thinking. Near the end of the month, when the Zapatistas temporarily evacuated Mexico City and units loyal to Alvaro Obregón appeared, the Casa committed itself to the “Constitutionalist cause” and the armed struggle.

The Casa’s final commitment of the urban working-class movement to the Mexican Revolution came about because of a convergence of interests on the part of the Casa, which wanted to advance working-class organizing, and Obregón, who needed troops. He sent friendly emissaries, such as Gerardo Murillo (Dr. Atl), Adolfo de la Huerta, and Antonio I. Villareal, to the union’s headquarters for consultations. Obregón offered the Casa the old Jesuit monastery of San Juan de Letrán, the Colegio Josefina, and the publishing facilities of the daily newspaper

La Tribuna in order to better carry on its organizing activities and to demonstrate his support of the syndicalists.

12 The Casa accepted the donations. Jacinto Huitrón, an avid agrarianist Zapata supporter and one of the most dedicated of the Mexican anarchists, accepted the keys to the Colegio Josefina from Obregón at a public ceremony. Huitrón agreed to allow the clerics and their students one additional day to evacuate the building. The following day Huitrón and some Casa members distributed the

colegio’s food stores to a hungry crowd that had gathered outside. Conservatives criticized him for “provoking disorder.” Inside, the Casa occupiers stripped the walls of religious images, tore apart confessionals, and otherwise eliminated all vestiges of religiosity. Obregón’s support of the Casa during this episode, despite some public resentment regarding the occupation of the religious buildings, made a strongly favorable impression upon the Casa leadership. Even the usually implacable Huitrón openly sympathized with the general.

13 Obregón’s efforts were well timed. The Casa anarchists had begun to have serious doubts about the seemingly radical Dr. Atl, who served in the delicate role of emissary between the Constitutionalists and the Casa. They noted that he always apologized for Carranza and denigrated the Constitutionalist movement’s “bourgeois” leadership. Hence, a deep suspicion developed regarding the direction of all three main factions—Zapatista, Villista, and Constitutionalist—in the Mexican Revolution.

On February 8, 1915, the Casa directors met in their Santa Brígida headquarters and cautiously decided to reject affiliation with the Constitutionalist movement because of its “bourgeois” nature and their general distrust of government. Speakers criticized both Atl and Carranza during the meeting. They also dismissed support of the Villa or Zapata movements as impossible in view of their religiosity and primarily “agrarian” orientation. The Casa was caught in the middle. At the end of the meeting, however, the urgency of the situation and Obregón’s “support of syndicalism” persuaded the directors to allow Dr. Ad to make a special appeal on the following day.

14Twenty-three syndicate secretaries and forty-four other members of the directorate attended the session. Dr. Ad rose to the occasion. In an impassioned and radical appeal for the “proletariat of Mexico” to come to the aid of “The Revolution” in the face of the serious “reactionary” challenge of the Villista and Zapatista movements, he conceded the right of the Casa to organize the workers nationwide. The directors discussed, debated, and finally overwhelmingly approved a declaration of armed support for the Constitutionalists. All the anarchosyndicalists present, including Quintero, Salazar, Barragán Hernández, and the

agrarista Huitrón, voted in favor of the resolution.

15On February 11 the directorate convened a general assembly of the Casa membership at the Teatro Ideal in Mexico City. A series of speakers endorsed the resolution of February 9; the only protest came from Aurelio Manrique, a member of the ultra radical Unión de Estudiantes, a Casa affiliate. He reminded the assembly of its principle of nonpolitical involvement, but ideology was more forcefully used to justify working-class participation in the revolution. The Casa saw its chance to become a major force in the revolution and feared for its existence if the armies of Zapata and Villa won the upcoming struggle. Enrique Arce and a half-dozen others opposed the decision of the majority and, in anticipation of the eventual outcome, they boycotted the Teatro Ideal meeting. Agraristas such as Díaz Soto y Gama continued to support Zapata, but the mutual affection between them and the Casa transcended the conflicts of 1915, and after Villa’s defeat they were welcome to return.

On February 18 a Casa delegation consisting of Quintero, Salazar, Gasca, Rodolfo Aguirre, and Roberto Valdés traveled to Veracruz and negotiated with Carranza representatives for several days. The discussions resulted in the famous Veracruz pact of February 20, 1915, formally committing the Casa to the Constitutionalist military effort. The delegation’s explanation for this commitment went far beyond the mere condemnation of the forces of Villa and Zapata as “the reaction” because of their alleged “Church and banker” support. They reasoned that the agreement ushered in a new era of anarchosyndicalist working-class organizing and working-class consciousness. They interpreted the pact as an agreement giving the Casa full authority to organize workers’ councils throughout the country. The Casa intended to immediately establish anarchosyndicalism as the organizational basis of the Mexican working class. The Casa delegates expected a later showdown with Carranza and his “bourgeois” supporters, but they already represented fifty thousand workers nationwide and felt that they controlled the situation.

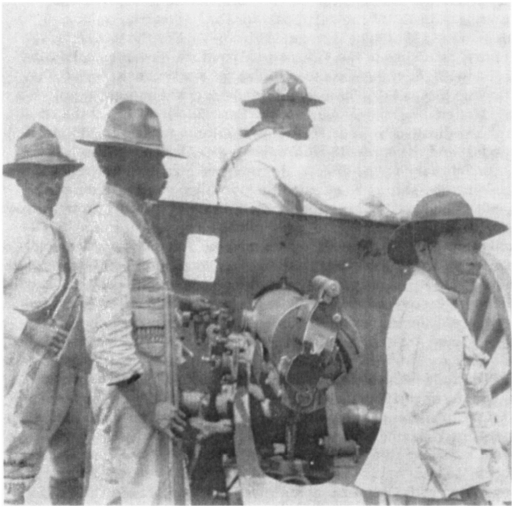

16The return of the delegation to Mexico City signalled an intensive recruiting effort that resulted in the departure in early March of seven thousand Mexico City workers for the Constitutionalist military induction training center in Orizaba. They were organized into six “Red Battalions.” The nationwide total of urban workers who took part in the revolution is uncertain, but the most reasonable estimate is twelve thousand, which included workers’ militias from the inception of the Constitutionalist revolution in the north and contingents from Monterrey and Guadalajara. They constituted a massive augmentation of commanding general Obregón’s Constitutionalist army. The workers acquitted themselves well at the major battles of Celaya, León, and El Ebano.

17 Commentators have disagreed with regard to the militias’ fighting capacity. But neither side in this dispute has produced any evidence to support assertions that must be regarded with caution by analysts. One should note the logistical shortages on all sides and the limited training available to all units, as well as seek a realistic perspective.

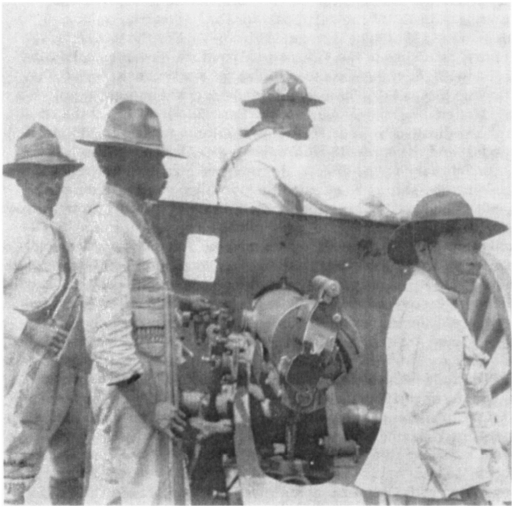

1. Red Battalion artillery unit stationed on the road from Cuernavaca to Juitepec to guard against Zapatistas. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)

Taking advantage of the organizing concessions granted by its pact with the Constitutionalists, the Casa leadership formed a Propaganda Committee (Comité de Propaganda) comprised of Mexico City and provincial syndicate heads. The committee, which numbered about eighty members, was divided into fourteen commissions of six members each. Each commission included a few members noted for their speaking and organizing abilities. Their task was threefold: first, to open preliminary talks with unorganized workers and to explain the national political situation and the Casa’s support of the Constitutionalists; second, to form local affiliates of the Casa and to neutralize the potential hostility of the local elites and press by not revealing revolutionary ideology or long-range plans to them; and, third, to obtain from the Constitutionalists “help and guarantees for the new adherents.”

18Despite the fact that the organizers carried credentials issued by the Constitutionalist government, or perhaps because of it, about ten died while carrying out their task. Rosendo Salazar and Celestino Gasca labored in Guanajuato while others carried on intensive organizing in Oaxaca and Orizaba.

19 In Morelia a delegation managed, after fifteen days of effort, to establish a Casa del Obrero Mundial with an affiliated union membership of thirty-five hundred. A general strike immediately ensued, and the Constitutionalist government adroitly responded by creating artisan workshops for carpenters, saddlemakers, cobblers, bakers, and tailors.

20 The painters received a commission to paint all of the city’s public buildings. Public anticlerical demonstrations were held and heralded the Constitutionalist cause as the “social revolution.” The successful Morelia organizing delegation then moved on to organize

casas del obrero mundial in Uruapan, Zamora, and Tlalpujahua. In Mérida, Yucatán, the local unions merged into a Casa “which pursues the same ends as that in Mexico City.”

21In spite of the overt cooperation that existed, even dependence on the Constitutionalist army, the most devout Casa anarchosyndicalists thought they could control the situation and not fall victims of government domination. Jacinto Huitrón could still declare that “the struggle between capital and labor is fatal and will continue to exist as long as money remains the regulator of society.”

22 The most vehement anarchosyndicalists joined in calling the Constitutionalist movement “the social revolution.”

23 They perceived the Constitutionalists in the radical perspectives offered them by Obregón and Dr. Atl, the able propagandist assigned by Carranza to the task of maintaining urban working-class support for the government and keeping the Casa in line. Atl, an effective speaker and the early mentor of some of Mexico’s greatest mural painters, including Diego Rivera, delivered “Jacobin-like” speeches at many Casa gatherings. A completely sincere revolutionist, he claimed that his newspaper,

La Vanguardia, represented the Constitutionalists, the workers, and the revolution. The result was a feeling among the anarchosyndicalists that the Constitutionalist movement was “radical,” “Jacobin,” and, despite Carranza, anxious for “La Revolución Social.” Atl called upon the workers to take “Direct Action,” and he impressed upon them the need for immediate results. He convinced many that the Constitutionalists and the Casa represented the working-class revolution that was shaping the future of Mexico.

The Constitutionalist-Casa military alliance paid quick dividends. With two Red Battalions in the campaign, Obregón’s forces won a series of strategic victories over their principal antagonist, Villa, and drove him northward into Chihuahua. By late 1915, Villa, isolated and in disarray, posed only a regional problem. The Constitutionalist forces controlled all the larger cities in Mexico, and the Casa established branches in Córdoba, Jalapa, San Andrés Tuxtla, Tlacotalpan, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Puerto México, Oaxaca, Tapachula, Tehuantepec, Mérida, Puebla, Tezuitlán, Banderillas (Puebla), Pachuca, Querétaro, Guanajuato, Celaya, Orizaba, Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas, Guadalajara, Irapuato, León, Morelia, Monterrey, Linares (Nuevo León), Colima, Tampico, Arbol Grande, Villa Cecilia, Ciudad Victoria, Nuevo Laredo, Saltillo, Torreón, Hermosillo, and Chihuahua.

24By late 1915, with their opponents defeated, the Constitutionalist amalgam of revolutionary elite and urban workers began to unravel. Open Casa support for the “International Working Class Movement,” and the existence of workers’ militias, provoked the concern of industrialists and conservative public officials. Unquestionably, a volatile situation existed with urban food shortages, runaway inflation, unemployment, public demonstrations, wildcat strikes, and battalion-sized units of armed workers in the field.

Carranza and the Ministry of Government (Gobernación) led by General Abraham González and Rafael Zubarán Capmany pragmatically attempted to deal with the growing crisis. In March 1915, the textile industry received government contracts theoretically designed to put thirty-five thousand workers back on the job. The Constitutionalists also passed liberalized labor laws which raised some workers’ wages and protected them from sudden layoffs without notice. These measures not only failed to deal with the critical problems of food shortages and inflation but also had no noticeable impact on the specifics they attempted to treat.

The economic and social crisis continued to deepen, especially in Mexico City. Hundreds of small businesses in the Federal District closed their doors and many larger concerns reduced both their production and workforces. Thousands of formerly employed workers in the environs of the capital city found themselves reduced to poverty and charity. Beggars were omnipresent.

25 Counterfeiting and a loosely managed flood of paper currency contributed to an inflation which further exacerbated the situation. Middlemen merchandisers came under fire from the Casa for profits which reached 15 percent on beef, already in short supply. After the Casa accused “Spaniards” of monopoly business practices and hoarding,

26 acts of violence against Spanish businessmen occurred. The Constitutionalist government resorted to fines to bring the violators in line with new governmental profit guidelines. In the outlying states some governors resorted to price controls and to government distribution of basic foodstuffs and clothing. Fortunately for the Constitutionalists, the public seemed to believe that the economic problems stemmed from the continuing war with Villa and Zapata. The Mexico City press confidently asserted that with peace the economy would be stabilized.

27While the economic crisis haunted the government, the Casa recruitment program benefited. During the first six months of 1915, in the wake of worker hardships and Constitutionalist military victories, dozens of new syndicates emerged throughout the nation and thousands of new members swelled the Casa’s ranks.

28 The newcomers had little ideological instruction. The propaganda committees had not yet taught them the concepts of anarchosyndicalism, antigovernmentalism, and the “class struggle.” Significantly, in addition to the anarcho-syndicalist ideologues, the newer members also heard appeals from less radical nonanarchist syndicate leaders, including Luis Morones.

During the second half of 1915, the heavy recruitment of new members into the Casa continued. Almost two dozen syndicates joined in November and December alone. The new syndicates continued to be organized in accordance with traditional artisan trade specializations which antedated the nineteenth century. Unlike the situation in northern industrialized western Europe, this tradition remained strong among the artisans, anarchists, and anarchosyndicalists of Latin Europe and the Spanish-speaking world. The new unions included the dyers, the biscuit bakers, the bed manufacturers, and the tobacco factory workers. Organizing success made the Casa leadership even more vocal and extreme in its propaganda.

Ariete, the Casa’s “official newspaper,” welcomed the new syndicates to “anarchy and freedom.”

29A wave of confidence swept the Casa directorate and the old-guard former Lucha members. They exalted the new syndicates as adherents of a “libertarian way of life” that would transform Mexico. The workers, “as are all those who are oppressed, all of those who feel as we do, … are marching dizzily [

vertiginosamente] toward true freedom. The Casa del Obrero Mundial has opened the breach. That is where we are going.”

30 The serious deterioration of the economy, the newly found sense of freedom on the part of urban labor, and the support of Obregón, Atl, and several other Constitutionalist officials all contributed to a sense of optimism among Casa organizers and accelerated the Casa’s rate of growth.

On October 13, 1915, the Casa enthusiastically inaugurated the Ferrés-Moncaleano goal of a full-fledged Escuela Racionalista at the Casa headquarters at Motolinia #9 in downtown Mexico City. The unveiling of a bust of the school’s theoretical creator, the Spanish martyr Francisco Ferrer Guardia, highlighted the occasion. Dr. Atl, Agustín Aragón, and Díaz Soto y Gama, among other speakers, addressed the hundreds of spectators. The school employed seven full-time instructors, required no enrollment fee or course prerequisites, and emphasized “free learning” as the primary necessity “for the disappearance of slavery.” Although an inadequate attempt in the struggle to redeem the Mexican working class, the school had considerable success. For the first time since the defeat of Huerta a year earlier, the anarcho-syndicalists implemented a part of their program which—as conceived by Ferrer Guardia and developed by Ferrés, Moncaleano, Luz, and Lucha in Mexico—the Casa national directorate considered to be crucial to the success of their effort to develop a class-conscious and fully mobilized Mexican working class. To the anarchosyndicalists, the Escuela Racionalista represented working-class control of the educational learning process. It meant the inculcation of the working class with “libertarian socialist” ideals.

31The armed conflict phase of the revolution concluded in most of central Mexico by late 1915. Most of the old-guard Lucha members survived the tumult and once again united in the leadership group at Casa headquarters. Quintero, Arce, López Dónez, and Tudó joined together as editors of

Ariete. The paper’s importance transcended the brevity of its tenure.

Ariete featured hard-line anarchosyndicalist ideology, including articles written by long-time Lucha members calling for the restructuring of the society and the economy around the newly formed Casa syndicates. Reproductions of revolutionary essays written by famous European anarchists—including Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, and a plethora of Spaniards—supplanted the Mexican tracts.

Ariete’s writers, editorializing for the Casa, anticipated that anarchosyndicalism would “break down the petty and selfish prejudices of trade unionism” and provide the Mexican working class with an expanded social awareness, an “advanced class consciousness,” and “modern ideas.” Mexican workers would then appreciate “national and international proletarian class unity” against the “capitalist exploiter.”

32 According to

Ariete, the syndicates were to serve as the new basis of politics and economic production in “Revolutionary Mexico.” The Casa leadership defined the Mexican Revolution in extremely radical terms and espoused doctrines completely unacceptable to the more conservative elements within the Carranza government. Because of these ideological differences, the hostility between government and anarchosyndicalist-organized labor deepened.

Runaway inflation and food shortages remained the extreme symptoms of a troubled Mexican economy and fueled working-class discontent through 1915 and 1916. Grocery store closings and bare shelves, Ariete charged, were caused by corrupt “monopolists” (acaparadores) who were “starving the people in a relentless quest for gold.” Inflationary prices further increased the tension. Organized labor reacted by demanding price controls, stricter regulation of currency, and higher wages. The government, convinced that it had already done enough, failed to respond. Consequently, a growing sense of workers’ unrest resulted in a series of sudden strikes.

The first wave of strikes provoked by this crisis occurred in the early summer of 1915 when schoolteachers and carriage drivers affiliated with the Casa walked off their jobs. Then, on July 30 the Bread Bakers Syndicate forced the bakery store operators to increase bakers’ wages, guarantee the ingredients in and the quality of their product, and lower prices, which the strikers claimed, had risen 900 percent in a few months.

33 The next flare-up took place in October when workers shut down the British-owned Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company (Compañía Mexicana de Petroleo “El Aguila,” S.A.), turned to the Casa for support, and then joined it.

34 In October and November the Textile Workers Syndicate struck and received a 100 percent increase in wages, the eight-hour day, and the six-day work week.

35 The Mexican labor movement had never before acted with such audacity or experienced so much success.

In December 1915 the strikes became even more serious. The Casa carpenter’s syndicate struck, paralyzed construction, and gained a 150 percent wage increase.

36 The buttonmakers and barbers followed suit and achieved immediate gains.

37 Striking Casa-affiliated miners, led by Elías Matta Reyes, a Lebanese immigrant, closed down the El Oro mining area on the border between the states of México and Michoacán. When the predominantly German and French owners used strikebreakers and violence in an attempt to reopen the mines, the miners resorted to sabotage of the mining facilities. Both sides committed physical assaults. In 1915 the Casa activists among the miners numbered 150 and they wielded tremendous influence.

38 The anarchosyndicalist leaders of the Casa openly challenged both capitalism and government and yet expressed confidence in their course of action. No era in the history of Mexican labor had witnessed the militancy and belligerence that the Casa demonstrated in the last six months of 1915 and first eight months of 1916. The pressure and turbulence were building up toward the general strikes of 1916.

On January 13,1916, during a period of increasing syndicate unrest and in the wake of Constitutionalist military victories, an alarmed President Carranza dissolved and disarmed the Red Battalions. When the discharged worker-soldiers returned to their homes, they found employment difficult to obtain and the Casa headquartered in the newly received, formerly prestigious House of Tiles in Mexico City. Jesús Acuña, minister of government and a member of the progressive Obregón-led faction of the Constitutionalists, had given it to the Casa as a token of his political good will. The returned veterans flocked to the House of Tiles for a seemingly endless agenda of organizational protest meetings and revolutionary lectures.

39The plight of the veterans of the Red Battalions, many of whom were unemployed and penniless, caused another abrasive dispute between the Casa and the government. The union leaders claimed that the men had been forgotten and cast aside. In January and February of 1916, the Casa petitioned for and demanded compensation not only for the impoverished veterans of the batallones rojos but also for striking workers whom it was claimed had been displaced by strikebreakers.

During the winter of 1916 Casa-sponsored street demonstrations, involving the veterans and other Casa members, criticized the government and demanded price controls, higher wages, and employment security. The demonstrations and protest marches usually began in front of the casa headquarters at the House of Tiles and often terminated at government or other office buildings. The veterans demanded government remedial action as compensation for their service to the revolution. On February 1, in reaction to the unrest, General González ordered his troops to close the House of Tiles meeting place and to arrest all those found on the premises. Simultaneous orders to close down regional

casas went to the governors of some states. A number of Casa national directors were jailed at the military headquarters in Mexico City (Jefatura de las Armas). Jacinto Huitrón, among others, was held in detention for nearly four months. In the meantime, the Casa leadership planned a protest general strike for the Mexico City area to be carried out by the Federation of Federal District Syndicates (Federación de Sindicatos del Distrito Federal), an amalgam of Casa syndicates located in the Federal District of Mexico, which included the capital city. In Veracruz and Tampico angry members of regional

casas staged street demonstrations, and the respective state governors declared a “state of siege” in order to regain control of the situation.

40During March 1916 the Casa continued its confrontation with the government by going through with plans begun in January for a “Preliminary” National Labor Congress to meet in the city of Veracruz. The congress was officially called by the Federation of Federal District Syndicates, which called upon the syndicates of the entire country to send delegates to help resolve the crisis which faced the Mexican urban working-class movement. Delegates attended from Guadalajara, the Federal District, and a number of cities in the states of Veracruz, Colima, Sinaloa, Sonora, Michoacán, Puebla, and Oaxaca. The raid upon the House of Tiles and the arrests of Casa leaders gave the congress, attended by representatives of more than seventy-three syndicate locals, an air of urgency when it convened on March 5.

41The governor of Veracruz, Heriberto Jara, a known radical in the Constitutionalist ranks, declined an invitation to address the congress, stating that the radical nature of the delegates’ ideas “could in no way serve the interests of the people.” Indeed, their radicalism far surpassed Jara’s. In their final declaration, the delegates proclaimed “class struggle” as a fundamental principle, defined syndicates as “resistance societies,” advocated “socialization of the means of production,” and excluded “any kind of political activity from the syndicalist movement.” The congress created the Mexican Region Confederation of Labor (La Confederación del Trabajo de la Región Mexicana), with headquarters to be established in the organized-labor stronghold of Orizaba, Veracruz. It was meant to be the Mexican regional organ in the long-held Spanish anarchist vision of an anarchosyndicalist world. The confederation, however, never really functioned. The congress, dominated by anarchosyndicalism, ended on March 17. It had not resolved the impending crisis in Mexico City.

42The Federation of Federal District Syndicates called the first general strike of 1916 to press home the long-sought Casa economic reforms and to protest the seizure of the Casa headquarters in Mexico City and the arrests of its leadership. It began during the early morning of May 22. All public utilities and public services ceased operations in the capital and most stores remained closed throughout the day. Thousands of workers marched toward Alameda Park in the heart of downtown Mexico City to hold a rally. General Benjamín Hill, commander of the plaza and charged with the security of the Federal District, met with a Casa delegation headed by Barragán Hernández, who gave him a list of demands addressed to the businessmen and industrialists of Mexico City. He listened as Barragán Hernández explained the workers’ plight.

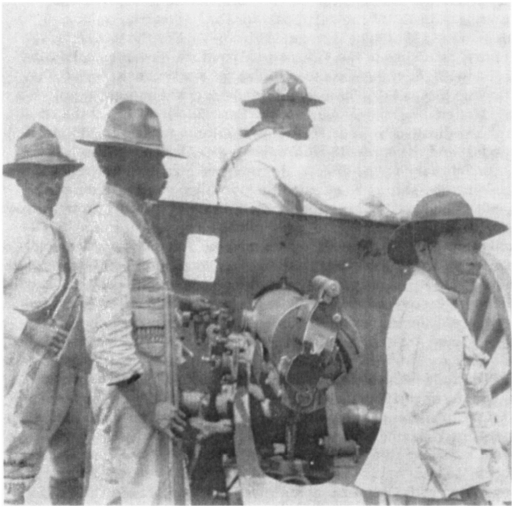

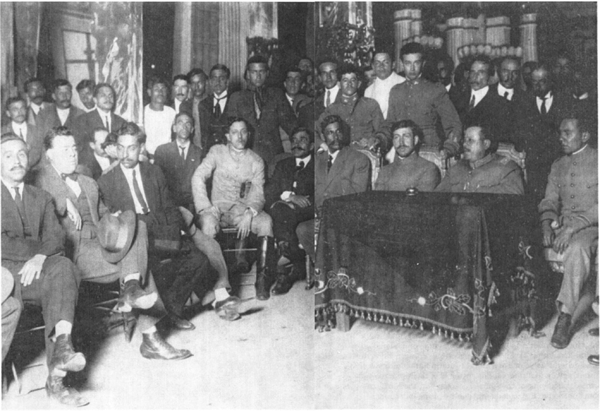

2.

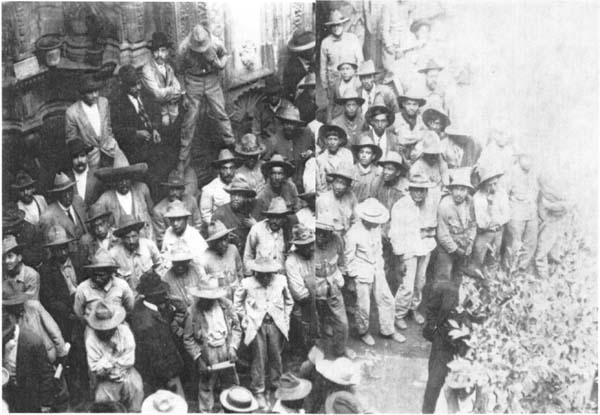

Meeting of returned and protesting veterans of the Red Battalions at Casa headquarters in the famous House of Tiles. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)3.

A group of workers outside the meeting rooms of the Casa in the House of Tiles. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)4.

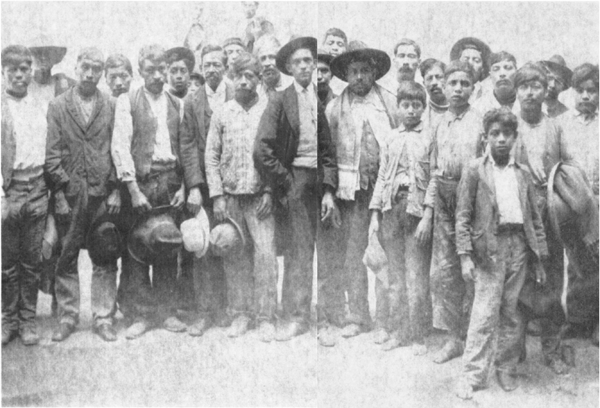

Part of the crowd which gathered in the Alameda Park on May 22,

1916, during the general strike. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)5.

Negotiating meeting between General Benjamín Hill and the Casa during the general strike of May 1916. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)Hill agreed to act as an intermediary between the Casa and the employers and also between the government and the union. He then issued a threatening ultimatum to all employers concerned to attend the public negotiations with the Casa or face arrest by his troops. Late in the day the electrical power and other vital transportation services resumed operating by mutual accord. The parties agreed to continue negotiations the next day when Casa leaders could meet with the full contingent of businessmen and industrialists in an open conference.

On May 23 the rival groups, including the government, came together in the Arbeu Theater (Teatro Arbeu) and resolved the crisis. Concessions obtained by the Casa included the mandatory replacement of company scrip money with valid government currency

(gobierno provisional) for the payment of workers’ wages. The employers also agreed not to reduce the work force for at least three months in order to protect the strikers from retaliatory dismissals. The workers were to be paid for time lost during the brief strike. Finally, any company decision to close down factory operations required prior clearance with the local military commander. In the Mexico City area that individual was General Hill. The government agreed to give the Casa another meeting place in lieu of the House of Tiles and to examine the Casa’s complaints regarding the arrests of some of its leadership but acknowledged no wrong doing and promised no further action. The Casa grudgingly accepted the building proffered by the government but never put it to regular use, because of its limited size and the belief that gifts from the increasingly hostile Constitutionalists should no longer be accepted.

43In the wake of the strike, progovernment liberals quickly attempted to bridge the widening gap between themselves and the Casa. Dr. Atl reflected liberal sentiments when he declared, “The strike … is not a reflection of discontent toward the government growing out of the Revolution, but a consequence of the [government’s] proclaimed principles of that Revolution.”

44 Successful government intervention during the first general strike of 1916 and the interpretation of revolutionary fulfillment given that intervention by the liberals were important steps in the development of the “official ideology” of the Mexican Revolution and eventual governmental control of the independent labor movement.

The general strike of May 1916 gained notable concessions for the Casa syndicate members; yet, rather than the strike heralding the final demise of the government and capitalism as the anarchists had predicted during the previous fifty years, the Constitutionalist regime demonstrated considerable flexibility in quickly settling the affair. At the time, the anarchosyndicalist leadership of the Casa sensed power and expressed confidence about the outcome. They did not see the inherent weaknesses in their organization, the lack of unity, and the virtually nonexistent discipline of the rank-and-file. Other labor leaders who signed the Casa-government agreement to end the strike, such as Luis Morones, the future leader of the Confederación Regional Obrera Mexicana (CROM), saw in the outcome the advantages of working with the Constitutionalists and enjoying their protection. The government thus built a bridge of confidence between itself and a new rising generation of pragmatic, less radical labor leaders.

Not all government officials were as sympathetic in their dealings with the Casa as Atl and Obregón. President Carranza and General González headed a conservative faction of the Constitutionalist regime in Mexico City that became increasingly hostile to organized labor. Significantly, government leaders saw the threat to their authority posed by revolutionary anarchosyndicalism. They also realized that the basis of the Casa’s strength—capacity to organize and communicate with the regional casas—relied upon the leadership, the urban meeting halls, and the armories. The government responded to the threat decisively and crushed the anarchosyndicalists during the second general strike of 1916. The most powerful, however lukewarm, supporter of the Casa, Obregón, although in Mexico City at the time, made no move to intervene when the president, provoked by the general strike of July 31-August 2, moved against organized labor.

During the summer of 1916 an agreement among bankers, industrialists, and commercial houses, and consented to by the government, to set the value of the Provisional Government

(gobierno provisional) peso at two centavos or one-fiftieth the value of the older gold-based currency, provoked urban labor unrest in Mexico City.

45 This action was probably taken to combat inflation, but it placed the major burden of that effort on the urban working class and wiped out the guaranteed wage gains made as a result of the May general strike.

Employers paid the majority of their workers in Constitutionalist currency; urban labor thus received a severe setback in real wages and a lowered standard of living. Strikes and angry, protesting street crowds became frequent.

46 The government rebuffed Casa appeals that it intercede on the workers’ behalf with new monetary regulations.

47 The survival of the average factory worker and the underemployed now depended upon the traditional lower-class means of marginal subsistence on the fringes of the money economy. Families went without new clothing and were reduced to the most basic foodstuffs while their children begged and scavenged for wood to use as fuel. If a once-proud worker could no longer pay the rent on the one-room family apartment, the omnipresent squatter-shanty towns and

vecindades that enveloped the city were ready to receive him. Men who took pride in their skills saw their positions deteriorating to the lowest socioeconomic extremity.

Given the desperate condition of the urban working class, the Casa decision to challenge both the revolutionary government and the financially dominant elements of Mexico City with the general strike of July 31-August 2 was an understandable although premature action. The anarchosyndicalists, with their organization only beginning to establish firm direction for its many new members, were in no position to challenge the government and its army.

The directorate (Consejo Federal) of the Federal District Federation of Workers Syndicates (Federación de Sindicatos Obreros), noting the government and capitalist refusals to reconsider the two-centavos valuation of the Constitutionalist peso, voted unanimously to call a general strike.

48 The goal of the strike was to force the government and the employers of the greater Mexico City area to agree to the payment of workers’ salaries in gold or its currency equivalent.

Syndicate leaders and organizers held secret meetings for several weeks in order to plan the strike and to avoid the perennial police observers at urban labor meetings. The general secretary of the federation, Barragán Hernández, a former Lucha member and one of the most forceful anarchosyndicalists of the revolutionary era, surreptitiously visited the various Casa syndicates in the Federal District and explained the strategy and the plans for the strike. Barragán Hernández also created three strike committees (Comités de Huelga). The second and third committees were to serve only if the first was put out of operation. The first committee included none of the principal syndicate leaders but did consist of ten militant Casa members : Esther Torres, Angela Inclán, Timoteo García, Alfredo Pérez Medina, Federico Rocha, Cervantes Torres, Casimiro del Valle, Ausencio Venegas, Cesar Pandelo, and Leonardo Hernández.

49Early in the morning of July 31,1916, the lights, the telephones, the public transportation, the drinking water, and all other public services in the greater Mexico City area ceased to function. Factories shut down and the retail stores failed to open. The approximately ninety-thousand striking members of the Casa closed down all normal activities in the Federal District.

Later the same morning, striking workers began to assemble for a mass meeting at the Star Salon, a frequently used working-class gathering place in downtown Mexico City. The strikers, fearing police intercession, arrived in small groups. Chaired by Luis Araiza and characterized by forceful and determined speeches, it was an excited meeting. In the midst of the session Dr. Atl arrived, bringing with him an invitation from President Carranza for the Strike Committee to meet with him at the National Palace.

6. Strike meeting at the Star Salon shortly before the mounted police, acting on President Carranza’s orders, attacked the crowd both inside and outside the meeting place, July 31,1916. (Photo gift of Ernesto Sánchez Paulín)

After a brief consultation, the nine-member Strike Committee agreed to meet with Carranza, announced their decision to the assembly, and departed with Atl. A few moments later the mounted riot police

(gendarmería montada), fully armed and still astride their horses, entered the theater attacking, beating, and dissolving the leaderless crowd. After some arrests, authorities closed the Star Salon and the rarely used “headquarters” given the Casa some two months earlier as a result of the May general strike and placed both under guard. In the meantime the Comité de Huelga, unaware of events at the Star Salon, met with the president. He denounced them as “traitors to the nation”

(traidores a la patria) and ordered their immediate arrest. President Carranza declared martial law at 5:00

P.M. the next day.

50August 1, 1916, passed in ominous silence. All public activities in Mexico City remained at a standstill while the military patrolled the streets. Sentries guarded all Casa installations, the Star Salon, and the various working-class neighborhoods where disorders occurred. August 2 began with a massive military parade and show of strength through the downtown section of the city. At the conclusion of the march, the soldiers gathered in front of the National Palace to hear the formal reading of the proclamation of martial law by Lieutenant Colonel Miguel Peralta. The proclamation charged the syndicates with an attack upon “public order,” “antipatriotism,” and “criminal conduct.” Citing the famous public order statute of January 25,1862, article one threatened those who violated “public order” with the death penalty. A violation of “public order” was defined as participation in any form of strike activity at factories or other institutions determined by the authorities to be in the “public service.” The penalties were to be dealt out in the summary manner prescribed by President Huerta’s emergency decree number fourteen of December 12, 1913, which Huerta had issued in an attempt to deal with the revolutionaries trying to topple his regime. Authorities arrested a number of Casa leaders, but no executions followed; the prisoners were held in the national penitentiary.

Restoration of electrical service to the city following capture of Ernesto Velasco, an electricians’ syndicate leader, proved to be a major turning point in the defeat of the strike. Under the threat of the most extreme punitive action, Velasco—whom police found in hiding, arrested, and roughed up—provided the military with the necessary technical information needed to restore electrical power. The restoraion of electrical power on the morning of August 2 demoralized the workers, and the poor status of Casa communications led many strikers to believe the strike was over.

On August 2, Barragán Hernández met with Obregón to ask for his assistance in guaranteeing the safety of the arrested members of the First Strike Committee and in opening negotiations with the government. Obregón, in what Rosendo Salazar regards as a fatal betrayal of the Casa, informed him that he underestimated the seriousness of the situation and warned that in order to avoid extreme punishments and further arrests the Federation of Federal District Syndicates and the Casa should “temporarily disband.” Barragán Hernández reported Obregón’s conclusions to the Second Strike Committee that evening. After a prolonged discussion, the committee voted to “recess” the Casa and the federation. The Casa was totally defeated.

51The strike failed because of a combination of factors : the use of strikebreakers from outside Mexico City in the operation of the restored electrical power plants, the devastating psychological impact upon the workers caused by the return of electricity, the arrest of the First Strike Committee, the closure of all Casa meeting places, the prevention of all street gatherings, the resultant lack of communications, and the intimidation caused by the extreme nature of the declaration of martial law accompanied by an overwhelming show of military and police force. A strategic factor in the failure of the general strike was its limitation to the Mexico City area. The Casa directorate did not dare to call upon the nation’s workers because of a realistic recognition of urban labor’s weakness in the states. The syndicates in other parts of the country simply did not enjoy sufficient strength to make a nationwide general strike work. Thus, the government, by concentrating its strength in the relatively industrialized Mexico City area, defeated the Casa.

52The trials of the twelve Casa prisoners before the military tribunal resulted in acquittal and release for all except Velasco, who received a death sentence. General Hill arrested the freed prisoners upon their release; a retrial also ended in acquittal. Public outcry and opposition to the extreme nature of Velasco’s sentence from within the ranks of the Constitutionalists persuaded authorities to reduce his sentence on April 11, 1917, to twenty years in prison. Finally, through the intervention of Obregón, Velasco was released on February 18,1918.

53Meanwhile, on October 10, 1917, the anarchosyndicalists received yet another crushing blow with the murder of Barragán Hernández. Attacked and wounded by a gun-wielding assailant in the street, he ran inside a nearby military station for refuge. His pursuer, José González Cantú, member of a prominent Mexico City family and a recently graduated class leader in a local military academy, followed him there and shot him to death. The onlooking soldiers did not stop or give chase to the murderer. The urban working class had lost one of its strongest leaders.

54