In about my twentieth or twenty-first year of teaching university biology classes, my students were preparing for an exercise, and I was explaining a couple of terms. One of these was homology—roughly, the same organs in different creatures—and as an example, I mentioned the arrangement of bones at the end of the front leg of vertebrate tetrapods. The term “hand,” I said, indicated one version of the same arrangement observed across all these creatures, and indeed ours is not much changed from its ancestral form.

Warming to my point, and encouraged by the little grunts or glances that I’m always looking for in class, I then truthfully reported that my wife—a veterinarian—and I had been changing our wiggling infant twins’ diapers just the past night or so, and one of us had said to the other, “Hold his front paw.”

One student’s face distorted in surprise, and she impulsively asserted, “That’s fucked up.”

Professors differ regarding what to do at such moments. I typically encourage an informal classroom, and my amused shrug apparently settled whatever tension might have arisen, so we all went on to the next phase of the day’s activity. But my little mental checklist received another mark: once again, I had seen the great divide in worldviews concerning humanity.

I’ll grant you, the student may not have personally and specifically represented that divide. It could be that she knew that the term “animal” or any slang-free reference to it is demeaning, and reacted to that, without necessarily buying into it. If so, it merely kicks the can down the road, though, to ask why that encoding exists, for her to tap into it that strongly. That would be the better question anyway—why culturally and symbolically the distinction is so available—rather than considering it in terms of one person’s psychology.

There’s a little biological detail to think about, too, which is that the human hand is evolutionarily less changed from its ancestral vertebrate structure, say, that of a salamander, than what we typically call a paw, say for a cat or dog. If we wanted to get derogatory with terms like this, it would make more sense to call one of their paws a “hand.”

It’s a divide. Humans are animals, or they aren’t, with any of the latter’s weasel phrases like “came from,” “but,” and “not just.” This divide is no joke, not only because it’s deep, but because it’s invisible. You can’t use education and profession as a guide. I’ve encountered it among other academics, including biologists, and even among evolutionary biologists and anthropologists. Nor is religious commitment an indicator. I’ve found that it might crop up among religious people of various persuasions, but it might not—that is, their positions may be the same as those of anyone else. And as my student demonstrated, one’s position on one side of it or another may not be acknowledged to oneself: even she did not know how strong her reaction was until it arrived.

How about you? Imagine, it’s diaper-changing time. The little children, boy and girl, are about six months old, able to sit up and scoot a little, but not yet crawling easily. Right now, they’re lying comfortably with their arms and legs waving about, smiling and cooing. One parent is a biology professor specializing in evolutionary theory, and the other is a veterinary specialist, but right now, they’re enjoying what to anyone else is a noisome job, wiping and diapering side by side, exchanging smiles with the kids.

One child, let’s say the boy, waves his arms energetically, creating minor issues with the nearest parent’s task. She says to the other parent, “Hold his front paw.” Both of them laugh, and to them it’s funny mainly because it’s true. The joke is not based on the misapplication of the term, but on the opposite—its complete aptness.

So, I ask you: Is the love shown by the parents in this situation diminished by knowing their son’s hand is a type of paw? How about their hopes for his future: Do they have less hopes, or different ones, from anyone else? Are they prone to treat him differently from other parents in terms of safety, discipline, health, or anything similar? Less formally, “What exactly do you think is so fucked up? What value does this distinction you’re making add, for anyone or anything?”

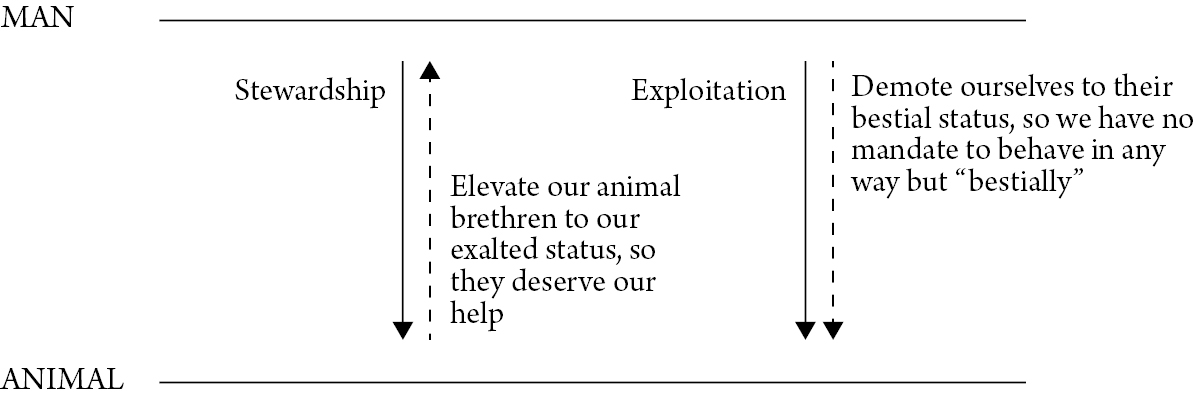

This distinction has a name: human exceptionalism, also called anthropocentrism. That’s the viewpoint that asserts that members of the species Homo sapiens are distinctive from all other living creatures, past and present, in ways that transcend ordinary or typical species differences. Or, as so many accounts state it, that we are not only unique in the sense of being a particular species, which can be said about any gopher or fungus or whatever, but in the sense of a kind of difference that merits special comment and consequences: “uniquely unique.” It is also—crucially—above the alternative (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Exceptionalism.

Human exceptionalism takes many forms, but it always includes two distinct components, each with a special implication.

•To assume or perceive a special inherent quality in humans, not merely in degree of difference from other creatures, but in kind: the uniquely unique feature. It could be cognitive, anatomical, spiritual, philosophical, cultural, or whatever, but it is something. Even if you can’t name it, you don’t have to, because you know it’s there.

•Also to include a consequential special ethical capability, by which humans judge their own and others’ actions, and adjust their own actions individually and as groups, that other creatures do not have.

•To infer or expect a distinctive role that humans are expected to take on, which they may either be doing already, or should start doing as soon as possible. This role is a sociological or political one, whether among fellow humans, directed toward non-humans, directed toward the larger economics and ecology, or all of them at once. It isn’t merely a preference or desire; you see it as a genuine and indisputable directive, inherent in human existence, which is literally immoral to violate or ignore.

•Also, to infer or expect a special fate, either awaiting our species or already in progress. Exactly what this is ranges all over the map and could be a book in itself.

The mantle of superiority is suspiciously vague. Any metaphysical outlook can serve—specific or vague, religious or secular. You can frame the unique quality in any way you like. You can use the language of God and the Bible, the Deep Green concept of Gaia, intuitive spiritualism, the racist distortions of Social Darwinism—any system of classification, even without explicit mystical content, as long as it includes the concepts of higher and lower, or even merely a subtle and unarticulated emphasis concerning superiority. That’s how more than a few evolutionary biologists and physical anthropologists can uncritically maintain what they call “weak” exceptionalism. For them, it’s all right to say a hand is a paw, as long as you frame it so that a hand is better than a paw, and that the processes resulting in a hand were either a special sort of evolution or a special achievement of evolution, not the boring kind that all those other creatures got or did.

The obligatory role is probably the real motor at work, because it is always explicit. It’s also completely flexible in terms of what one is directed to do, so that both sides of a controversy may share the presumption of special human privilege and responsibility. When that happens, it’s an intellectual and political disaster: the discourse goes around and around, neither side ever gaining ground, because to attack the other’s argument at its root would be to undermine one’s own.

I’ll use the issue of how we, people, should act toward nonhumans or, more generally, toward “nature.” It’s a fixed feature of exceptionalism that we simply must adopt some special role toward the other creatures because of the separate and elevated status, as shown by the two levels in Figure 1.2. The arrows in Figure 1.2 illustrate that both stewardship and exploitation can rely upon this shared framework, such that they compete for the status of having this special, directed, and obligatory goal. You can also play tricks with how you phrase the human superiority in ways that give both sides something apparently fundamentally opposite to argue about. That’s what the dotted lines are.

Figure 1.2 Exceptionalism, stewardship, exploitation.

See how sneaky that is? Each statement looks as if it’s willing to equate humans and nonhumans, and as if it’s opposed to the other statement, but the categories of superior Man and inferior Beast are as fixed as ever. And even better, now the good-of-the-animals stewards and the good-of-humanity exploiters can butt heads all day long, each with a designated enemy, so the discourse can dance up and down those dotted lines. One side can even call out the others’ exceptionalism and thereby keep its own obscured. The whole construct is intellectually empty, logically supporting nothing but available to justify anything, and so very attractive.

Human exceptionalism never, ever asks, “All right then, what is a human being, and how does it relate to the various other living things we see?” These are great questions—sadly, left behind in history, only partly addressed.

The exceptionalism question is all bound up with the origins of biological science, or the origins of a particular phase of it. Scientific thinking is as old as human culture, but modern, institutionalized science and its specific framework of ideas took their shape during the nineteenth century. The first big issue for biology was to make it a part of chemistry, which also came with making chemistry a part of physics. In Distilling Knowledge, Bruce Moran marks the transition for chemistry in the early 1800s, when it shed superadded forces, those of magic and metaphysics. This transition was dramatically evident between the eminent English surgeon John Abernethy, a key member of the Royal College of Surgeons, and his former student, William Lawrence, who was elected to the College in 1812 at the age of thirty. Abernethy considered the essentials of chemistry, magnetism, and electricity to be evidence of superadded forces, whereas Lawrence argued the more radical position, that these very things were wholly physical phenomena like anything else—and further, that being alive did not rely on a superadded quality.1

Lawrence had an ideal platform to present this view: the Hunter lecture series, which he began in 1816 and published as he went, with a summary volume in 1819 titled Lectures on Physiology, Zoology, and the Natural History of Man. The third lecture in the series and the introduction to the published volume include the clearest possible argument then or since:

Life, using the word in its popular and general sense, which at the same time is the only rational and intelligible one, is merely the active state of the animal structure. It includes the notions of sensation, motion, and those ordinary attributes of living beings which are obvious to common observation. It denotes what is apparent to our senses; and cannot be applied to the offspring of metaphysical subtlety, or immaterial abstractions—without obscuring and confusing what is otherwise clear and intelligible. (William Lawrence, Lectures on Physiology, Zoology, and the Natural Rights of Man, Lecture II, p. 52)2

And,

To talk of life as independent of an animal body—to speak of function without reference to an appropriate organ—is absurd. It is in opposition to the evidence of our senses and our rational faculties: it is looking for an effect without a cause. We might as well reasonably expect daylight while the sun is below the horizon. What should we think of abstracting elasticity, cohesion, gravity, and bestowing on them a separate existence from the bodies in which those properties are seen? (Ibid., p. 53)

Lawrence had struck a blow in the current culture wars about materialism and vitalism, terms with specific meanings at that time. Abernethy’s vitalism held that living things contained or included some special essence that powered and literally animated them, making them alive and imparting certain properties; this essence was variously described, but it always included an expression of intent or what today we might call spirituality. Lawrence’s materialism, on the other hand, meant physical properties affecting one another in reality, literally what you and I today call physics and chemistry. To explain life materially, you asked about and examined physical properties, more or less as if you were studying an engine. Lawrence had exposed the fact that many scientists in different fields were investigating life materially, and he provided a framework, even a name, for talking to one another about it.

The word biology in English dates from these writings and from this exact point. Although its precise author is obscure (Lawrence cited a German naturalist, G. R. Treviranus), credit for its adoption and its strict material basis lies with Lawrence, and his meaning requires careful attention: that life is a physical phenomenon, without the need for superadded forces or irreducible phenomena to explain or to study it. In a word, biology means studying life as a subset of chemistry, itself a subset of physics. Lawrence urged his audience to seek out every imaginable physical understanding of all organisms’ diversity and functions they could conceive, and to understand them as physics and chemistry operating in the real world.3

He was surgically precise in his introduction to the Lectures, in direct reply to Abernethy, explaining that even if living things were special and consequential in some spiritual way, this way is not manifest in their structure, processes, and dynamics, which Lawrence called the “economy” of an organism. In other words, he did not attack anyone’s belief in a spiritual existence or purpose, but rather he said something infinitely more powerful: that such belief would have to putter along on faith alone, without using the existence of living beings as a constant body of evidence.

From the very start of Lawrence’s lectures, the establishment church, medical community, and educational curriculum recoiled in horror. English churchmen, politicians, and scholars perceived material thinking as a terrifying strike at morals, social stability, and their positions of status. They put much effort into articulating and supporting vitalism throughout several opinion-making publications like the Quarterly Review, including direct attacks on specific scientists and their investigations. As scholars were supposed to represent only the most well-regarded, upstanding virtues as judged by the privileged, such attacks were career destroying and amounted to thought policing (what today we call “control of the narrative”). Even as the lectures proceeded, Abernethy attacked Lawrence as both unpatriotic, for referencing foreign scientists, and immoral—even as conspiring to destroy morality. Lawrence responded defiantly in the collected volume, to say the least, and the infuriated Abernethy brought the full power of his privilege upon his former student to suspend him from his position, effectively threatening his social and professional destruction. In 1822 the Court of Chancery drew upon ancient laws to declare his book blasphemous and to rescind its copyright, which perhaps backfired as a cultural strategy, as it instantly went into multiple cheap printings and sold like gangbusters.

Lawrence was forced to repudiate his views in order to save his career, but in terms of raw science, he was the winner. From that point forward, scientific studies of organisms, and also of everything else, became more and more committed to the concept of physical cause as the sole topic of interest. This principle is so fundamental to our modern experience of science that it’s hard to remember that previous forms did not share it. To claim that life is itself a physical phenomenon, such that analyzing its properties and causes need not consider any presumed purpose for life, or any nonphysical “vitalizing” property, is more than a mere “step” of scientific history. It’s a game changer.

In the following decades, two concepts were developed: the periodic table of elements and cell theory, which together form nothing but the most exquisite confirmation of what Lawrence had suggested and lie at the heart of biology as we know it (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Chemistry and cell timeline.

I’d like to focus on the chemistry for a moment. In the early 1800s, no one realized yet how few elements existed, how easily organized their interactions are, or how chemically unified all of known life is. It’s one thing that Lawrence was right; it’s another how simple the mechanisms are.

The chemistry is so easy you won’t believe it. At the time of this writing, we know of 118 elements, but to understand the chemistry of life, you only have to know about five of them: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus. Others are involved, but these five make the organic macromolecules (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Macromolecules.

Carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen make two (relatively) little molecules called glucose and fructose. They’re the carbohydrates—specifically, the simple ones. Every other named carbohydrate is merely a tinker-toy combination of these two, so those are called complex. Sucrose, table sugar, is fructose + glucose. Starch is another, merely bigger. Other words for “carbohydrate,” exact synonyms, are sugar and saccharide.

In biology, the two simplest carbohydrates are the source of bodily energy for nearly every living thing on the planet, through the mechanisms of metabolism. More complex carbohydrates are either ways to store this energy prior to its use, or structural features of bodies, such as cellulose in plants, packed tight to become wood in some of them.

If you chemically condense a carbohydrate, so that it’s smaller and (in energy terms) richer, it’s a fatty acid. A bunch of fatty acids stuck together are a lipid; lipids get more complicated depending on what else is stuck to them, but the relevant point is that all cell membranes, on the whole planet, are based on the same lipid arrangement. Lipids are also used to store energy prior to use, such as fat in animals, and a few of them, the steroids, are hormones.

Before going on, imagine this: almost every cell on the planet has the same lipid membrane and the same metabolic activity, based on those three elements. That’s right. Observed differences in those things are merely add-ons.

If you add nitrogen, technically nitrate, to a simple carbohydrate, you get an amino acid. There are only twenty of them, but any can hook up to any other in a chain structure—that’s what makes a protein. Proteins are therefore the most diverse biochemical structures, effectively an infinite number of possible orders and lengths in a chain, each one subtly different in its reactions. Proteins are what make cells different from one another, through structures embedded in the membrane, through managing what gets in and out, and through whatever gets made in the cell and squirted out. Famous structural proteins include hemoglobin, pigment, and keratin, the stuff your hair and nails are made of. Enzymes and most hormones are also proteins.

If you add a phosphate to an amino acid, you get a nucleotide. They can also be combined into chains, making nucleic acids, including the universal inheritance molecules called ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), as well as the famous metabolism molecule, adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Living things indeed look differently than nonliving ones, and they do things that nonliving ones don’t. They have structure, active and reactive properties, energy acquisition and storage (metabolism), and inheritance, when those macromolecules are organized in a certain way, called a cell.

That single tricky thought required decades of work throughout the nineteenth century by Matthias Schleiden, Rudolf Virchow, Theodor Schwann, Louis Pasteur, and August Weisman, culminating in the idea that cells are alive, formalized into a set of points called cell theory. This idea includes the possibly disturbing insight that creatures are heaps of cooperating cloned cells, organized as tissues, organs, and organ systems.

This is why biology teachers today seem obsessed with the interior of cells, right out of the gate. When Lawrence delivered his lectures, the outlook he presented so clearly was only that—a way to look at life. But the research he inspired eventually produced a core conclusion that cells, previously observed but not thought of in this way at all, were not only living things, but also the smallest individually alive things, or “units of life.” You probably had to memorize that at some point, but maybe you missed the point: a body has no life of its own, but is an organization of living bodily cells constantly reproducing and dying, with its own properties. You as a person, with your name, your sense of existence, and your identity, are best understood as an organized property of tiny living things. What we call being alive, as people, is a matter of maintaining the relevant organization, for a while anyway, and what we call reproduction, as offspring or children, is a matter of some of the cells persisting in a new organization.

There are a million more details, as any biology major can tell you, but not one overrides what I’ve just explained: that the chemistry remains brutishly simple, no matter how complicated and gaudy the cells and their larger organizations may be. All the rest of biochemistry is about putting together and taking apart the macromolecules, and managing water using salt concentrations. Biological diversity—different creatures living in different ways—is a matter of add-ons and elaborations, defining the groups we call domains and kingdoms.4

Let’s keep going with that “unit of life” idea. Because the cell is the smallest unit of life, therefore none of its components (membranes, chromosomes, etc.) are considered alive. Think about that! Living creatures are made wholly of nonliving substances. There is no “living stuff” in the universe, because being alive refers only to a certain category of how some nonliving stuff sometimes interacts. When you had to memorize that diagram full of cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticula, you were getting Lawrence channeled to you. It means that just because you are a living thing, you do not cease to be a thing.

I use the “you” with plenty of justification. Lawrence had not spared humanity the depth of his insights, far from it—fully half of the lectures’ content is dedicated to human functions and diversity, described in the same terms and standards of analysis as any other organism.5 The response included extensive, ongoing, and influential writing for the following six decades. The insight and its implications was definitely not lost on Friedrich Nietzsche:

Let us beware of saying there are laws in nature. There are only necessities: there is nobody who commands, nobody who obeys, nobody who trespasses. Once you know that there are no purposes, you know there is no accident; for it is only beside a world of purposes that the word “accident” has meaning. Let us beware of saying death is opposed to life. The living is merely a type of what is dead, and a very rare type. (Nietzsche, The Gay Science, p. 168)6

Before these debates and writings began, however, someone else got there first, at the most relevant, challenging level. One of Lawrence’s friends and an attendee of the lectures was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, newly Mary Shelley by marriage, a young scholar who not only perceived his points but immediately dramatized them in her first novel in 1818: Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus. But it wasn’t the novel you may be thinking of.

The popular word “Frankenstein” is so entrenched as to defy meaningful rehabilitation, even for those who know that the name refers to the scientist rather than his creation. It’s identified with irresponsible research applications that transgress certain lines, promising woe to innocents, to the perpetrators, and to the creations themselves, who are some combination of malevolence and misery. It’s what I call the “don’t meddle” story, to be discussed further in Chapter 3.

The most-often read version of Shelley’s novel was published in 1831, adding much talk of God, tagging the created man as soulless and self-loathing, and tagging Victor Frankenstein as a blasphemer punished for his transgression, as well as Shelley’s introduction reinforcing all these points.

The original 1818 publication of Frankenstein isn’t this story at all. The English scholar Marilyn Butler has provided great, wonderful service in calling attention to the original, which saw only tiny print runs, and its republication usually includes her essay “Frankenstein and Radical Science.” She outlines the direct link between the story and Lawrence’s essays, the development of the alternate, vitalist message during the 1820s, and the pressure brought against Shelley to force the compromised edition.7

What’s the difference between the two versions? In the 1818 version, the story centers on the twin facts that Victor Frankenstein is not a sorcerer who toys with forbidden forces, but a research engineer who works strictly with scientific chemistry; and that his creation is not a failure, or deficient in any way, but is instead a successfully created person. Frankenstein’s methods are not arcane occult deviations from science, but rather an utterly physical extension of existing science. It forces the reader to cope with the fact that human beings are chemical, physical phenomena.

Crucially, Butler shows that the content in the sections cut from the original corresponds exactly to the material that the influential and hostile reviewer George D’Oyley in the Quarterly Review had insisted be cut from Lawrence’s book. It was a cultural counterblow that combined these cuts, additional text to include the concept of Nature’s or God’s vivifying quality and tie it to an intrinsic morality, and Shelley’s new introduction, which downplayed the novel’s origin into a “ghost story” anecdote.

I’ve used the original text in class, and people struggle to read it fairly. Part of the problem is the movies’ influence. I have to use short readings, in-class exercises, discussion groups, and focused questions for students to read the words de novo and finally to grasp that the creation is not a stitched-up corpse, that Victor does not use magic or even electricity, that he is not interested in being God, and especially, that his project is fully successful. They have to consider that Victor’s judgmental language about the “demon,” the “fiend,” the “hideous wretch,” should not be mistaken for the physical descriptions, none of which are quite as bad as the invective.

The difficulty continues with the plot events, in throwing aside the whole “the creation is rudimentary and goes berserk” model, and eventually realizing that the created man’s capacity for evil is fully human, not inhuman or subhuman. In this, I have to help the students avoid looking for symbolic meaning or repeating what they think they know, and instead to focus strictly on characters’ actions and responses to one another. When one of them says, “But it’s a monster! It kills people!” I have them look again at whom the created man kills, and why. Then they realize that he is not a rampaging berserker, that this is not flailing-around killing, but rather that he murders people—exactly the way real people murder, motivated in ways a real person can understand and judge to be morally wrong, because a real person did it.

Victor’s personal arc is marked by repeated reversals of his mood and goals, in the first half shown by his intense drive to create a human life flipping to his rejection and effective denial that he did it. In the second half of his story, he piles on such reversals faster and faster, until it’s hard to see there’s a Victor at all, instead of the next rebound from whatever he was just doing. His only act of thoughtful rather than impulsive, driven agency is to abort the woman he’s creating in defiance of his agreement with the man. The created man’s personal arc is extremely different and absolutely linear, each step marked by trauma and the development of more personal agency, from near-helpless infancy through suffering childhood, vengeful adolescence (which includes murdering William and indirectly Justine), and finally the decision to look his creator in the eye and demand recognition and the chance for a complete life, a promise he successfully gains. When that promise is betrayed, he quite precisely kills Victor’s best friend and his fiancée, and indirectly his father, forcing Victor to be closest to none other but him and effectively to resign his fate into his, the created man’s, hands (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 The plot of Frankenstein.

The story is so grim and headlong because it’s all about murder, really: the two early in the created man’s life, to which Victor becomes his post hoc accomplice, and the two or effectively three committed by the created man in vengeance for the destruction of his mate. The rest of the story concerns their mutual flight into the Arctic, where Victor dies and the created man takes the body into the wilderness, presumably to die at the Pole.

The one moment at which the created man has the most wide-open decision regarding what to do with himself, and at which Victor has the most focused, non-rebounding opportunity to act, is when Victor aborts the created woman just prior to her completion.

Why does Victor do it? It’s not a matter of the created man’s wicked deeds to date—Victor actually gets that part, that they reveal him to be more human rather than less, and he knows very well that his own silence played the key part in Justine’s hanging. He even agrees to the proposal of creating the woman, in exchange for the creation retiring to the wilderness—until he backs out at the last moment and destroys her. Again, why?

The text is explicit in two places. Regarding one of them, right before Victor violently dismembers her body, I agree with Butler’s assessment that his mass of fears about the possible future of such a couple do not correspond to his priorities at any other point in the story and are best interpreted as excuses. I think more content is found in the other passage during the earlier confrontation, as he considers the created man’s request and experiences two completely different feelings at once:

His words had a strange effect upon me. I compassionated him and sometimes felt a wish to console him; but when I looked upon him, when I saw the filthy mass that moved and talked, my heart sickened and my feelings were altered to those of horror and hatred. I tried to stifle these sensations; I thought, that as I could not sympathize with him, I had no right to withhold from him the small portion of happiness which was yet in my power to bestow. (Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, p. 121)8

Victor’s invective toward his creation is usually repetitive, but at this moment it’s unique and quite clear: he describes the created man as physically a “filthy mass that moved and talked.” It’s opposed in this passage to a different feeling of some empathy and responsibility, which at the moment he acts upon in agreeing to the proposed task. Ultimately, however, he acts upon the prior feeling of pure revulsion: he will not afford his creation even the status to be judged morally, or to consider his position or interests in any sympathetic way. In Victor’s single moment of considered decision, he deems the created man not alive, and therefore out of bounds of human consideration of any kind.

That’s the part that hits hard, way too hard for the Anglican political establishment of the early 1800s, and probably too hard for easy reading today. The created man is a person and a filthy mass, because—that’s what we, the real people, are. Abernethy had denounced Lawrence with all the incoherent rage an ego-stung advocate of the exceptional Man could muster. This younger, junior scientist was deliberately, villainously seeking to destroy morality, he was in league with foreign agents (French ones! good God!), and he was effectively a psychotic intellectual terrorist. Why? Because Lawrence had frightened him with the utterly logical suggestion that aliveness is a matter of chemical operations, that real-world, real-life behavior is an organic function of the mind, and that although one may believe in a mystical soul, such a thing cannot be observed as the seat of morality, or as the seat of anything we see people really and actually do. This fright was not merely philosophical, but was politically associated with every bit of status and privilege that people like Abernethy enjoyed.

In the fiction, that is why Victor twice recoils from his creation, not because he’s not alive, but because he is. When he begins even for a moment to consider the created man human, briefly to think of his emotions, Victor instantly retreats into hatred—because that humanity too evidently exists without miraculous mystery. He cannot bring himself to see that just because the created man is a thing, that does not prohibit taking him seriously as a living thing.

I don’t expect you to agree with this reading—everyone knows the “monster” is hideous—even Wikipedia says so. Everyone knows it is “soulless,” that it “should not exist,” that Victor’s constant and strict avoidance of personal pronouns (he, him) indicates what the book “means.” But I submit that my reading is consistent with the original text and that the “soulless” reading is not.

Teaching by hammering students with some assertion doesn’t work, nor is it my goal to force people to agree, or to pretend to. Here’s what I did with them instead.

Format: 5 typed double-space pages with no extra spacing at any point, using standard margins. Include a cover page with your name, the title, the class information, and the date. Answer all four questions, in this order. Do not bullet or number them, and do not include any introductory or concluding paragraphs.

Identify a function or feature in Frankenstein’s creation that must rely on some processes familiar to our own physiology, either because Frankenstein simply copied it or because he found a way to simulate it. (Example: we know the creation eats. There are others.) Explain how that function or feature works in our bodies.

Imagine a thinking creature whose body’s physiology involves less physical substances than ours—perhaps mainly sunlight, gases, and connectors to conduct energy like electricity or light. Upon examining us and the human body to the extent that you have studied in this class, it pronounces a human to be “a filthy mass that moves and talks.” Defend your honor and that of your species against this insult! Or conversely, agree with it. Either way, explain your position.

Is Frankenstein’s creation human? Explain your answer in detail. You may have to divide the term into different meanings and address them separately.

You are a skilled cinematographer and film editor. Choose any scene in the novel and describe how you would design and create it in cinematic terms to achieve the maximum and accurate thematic impact you think it deserves.

It’s quite wonderful to read twenty-five entirely different, thoughtful, slightly traumatized papers answering these questions, from students who’ve been studying macromolecules, cell structure, metabolism, anatomy, and physiology throughout the term. Few students consider literature and science class compatible, and even the science fiction and fantasy fans aren’t accustomed to radical social science fiction: informed, confrontational, with no nostalgic looking back, and no idealistic looking forward.

The nineteenth century rolled on and biology was becoming itself, as the modern forms of biodiversity, evolution, ecology, development, and genetics formed right along with cell theory. In some ways, the larger culture was recapitulating Victor Frankenstein’s moment of reaction at the creation’s birth: half in a state of excitement and half in a defensive crouch, as the scientific development of the question “What in the world is a human person?” was under way.

The question’s focus would change, however. Whether humans are chemicals may be a profound issue, but it’s abstract in terms of personal experience, ethical crisis, and setting policies. The ensuing debates and the issues around which entire political and cultural movements would coalesce were more visceral and personally jarring: whether humans were animals, specifically apes, and how humans were to treat nonhuman animals in a variety of contexts, especially scientific research.

The early context for these debates was the voluminous, anonymously published Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation from its first edition in 1844 through its twelfth by 1884. The final edition revealed its author to be Robert Chambers, who had died in 1871. This book was really the groundbreaker. Shocking in its presumption of material causes and human’s place in them, it also managed to downplay the radicalism of the idea, pitching such causes as part of a grand design, and therefore more palatable to the English-speaking mainstream. Everyone read it, it spawned a reactive secondary literature, its anonymity lent it both a certain naughtiness and immunity from authoritative backlash, and its long run with multiple editions generated a culture of seeing “what’s in it this time.”

During the Vestiges’ forty-year run, not a single work of natural history or other biologically related work can be properly considered without checking the publication date for its latest version, and its hottest topic was the historical and constant transformation of living things. Crucially, it subtly transformed Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s evolution, then associated with revolution, the bloody one in France, into development, a benign and ordered process. Even with that softening of content, it popularized the discussion and provided a common background and vocabulary for the larger culture’s opinionated, interested debate about it—including the status of human beings as biological entities. Some of that material was hard core even by today’s standards and might fairly be regarded as Lawrence’s revenge:

Less clear ideas have been entertained on the mental constitution of animals. The very nature of this constitution is not as yet generally known or held as ascertained. There is, indeed, a notion of old standing, that the mind is in some way connected with the brain; but the metaphysicians insist that it is, in reality, known only by its acts or effects, and they accordingly present the subject in a form which is unlike any other kind of science, for it does not so much as pretend to have nature for its basis. There is a general disinclination to regard mind in connexion [sic] with organization, from a fear that this must needs interfere with the cherished religious doctrine of the spirit of man, and lower him to the level of the brutes. A distinction is therefore drawn between our mental manifestations and those of lower animals, the latter being comprehended under the term instinct, while ours are collectively described as mind, mind being again a received synonym with soul, the immortal part of man. There is here a strange system of confusion and error, which it is most imprudent to regard as essential to religion, since candid investigations of nature show its untenableness. There is, in reality, nothing to prevent our regarding man as specially endowed with an immortal spirit, at the same time that his ordinary mental manifestations are looked upon as simple phenomena resulting from organization, those of the lower animals being phenomena absolutely the same in character, though developed within much narrower limits. (Robert Chambers, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, chapter 17, pp. 325–326)9

By the 1850s, this discussion could no longer be controlled by clergymen and their academic allies, and younger scientists were publishing their ideas about it openly. Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species was one of these, first published in 1859, proceeding in six editions through 1872. Contrary to popular misconception, this book offered little regarding humans, but it was the watershed for both the theoretical underpinnings in our understanding of living things’ diversity and the social clout to publish such things openly. One reason for that was the role of Thomas Henry Huxley, who decisively defended Darwin’s theory of natural selection and the associated issues of human origins against all comers, fellow naturalists and theologians alike. The Origin gained its immediate social and intellectual fame at least as much from Huxley’s spirited defense of evolution against Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in a post-seminar discussion at Oxford as from its own content, which is—between you and me—scientifically brilliant but a little bit bland when it comes to Man, Nature, God, and so on.

Speaking of nature, Huxley was one of its forces all by himself. Unlike Darwin and many of the other notable intellectuals in this period, he was raised not only middle class but also poor, and rather than groomed through privileged schooling, was apprenticed to harsh, grubby medical work in the 1830s, in the depths of Britain’s worst depression. Self-taught in many topics from languages to philosophy to theology, he won top national awards in anatomy and physiology at the age of twenty; at the unbelievably young age of twenty-six, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society and was soon elected to its Council. Huxley was a walking challenge to the Victorian social hierarchy, curiously placed in its corridors of power, practically a time traveler from the next generation, free of the implicit indoctrination of both church and privilege, and he feared literally no one in debate or policy discussion.

Huxley was one of the few of this time who engaged directly with the question of humans as animals. His friend Charles Darwin was another, studying complex nonhuman behavior and writing of thought as a “secretion of the brain,” and their respective work carried on the direct line of intellectual descent from Lawrence. Huxley’s lecture “Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature” in 1863 provided the first really public, evidence-based demonstration that human beings were properly considered a type of animal—specifically, an ape. He also helped develop the link between cells and organisms in his lecture “On the Physical Basis of Life,” in 1868.

By this time, the other major issue centered in human exceptionalism had developed dramatically as well: the general treatment of animals, with a special emphasis on the subjects of medical research. Huxley’s prominent position in education and research policy placed him right in the center of the controversies concerning the Anti-Vivisection Bill in 1875, to be discussed in Chapters 2 and 4.

The early 1800s were a defining intellectual moment for biology as we know it today, and the 1890s were similar in terms of social positioning: the birth following the earlier conception, perhaps. Today’s academic degrees, job descriptions, scientific organizations with their peer-reviewed journals, and other defining social elements of modern biology all took their form at this time. Intellectually, the different avenues of inquiry were tagged as a unit, and even if most of it was marked “to be figured out in detail later,” these markings were now acknowledged. One of those unknown areas, now designated as such and recognized as crucial, was inheritance, and that’s why Mendel’s overlooked work was uncovered—it wasn’t because someone happened to trip over it.

Evolution as an idea and, with it, human identity as a physical and biological phenomenon had suffered along the way. Early in the nineteenth century, it was primarily associated with radical politics and was considered shady, even subversive. Later, as a more mainstream term, it shook out into two distorted forms. The one favored by most intellectuals, deemed tolerable by the more powerful churches, and folded into scientific education, was a lovely confection of progress and the ascension of human to a current exalted position, and helpfully suggested what to do next. The other, made most famous by its vigorous articulation by industrial magnates in the United States and soon to take hold on the popular and cultural associations with the words “natural selection,” “survival of the fittest,” “evolution,” and “Darwin,” was a grubby justification of ruthless commerce and imperial colonial policy marked by considerable racism, even more disconnected from scientific content.

In 1893, in the Romanes lecture series at Oxford University, Huxley boldly defied both of these distortions, in the last lecture and publication of his life, Evolution and Ethics, which was published in 1895 with an additional Prolegomena. It was the Lawrence-style lecture of its day, entirely counter to the comfortable placement of scientific knowledge in the corridors of power and privilege. Huxley had not lost sight of the ideas that life and humanity are a thing, and that this thing happens to be an animal. How, he asked, is this to be reconciled with questions of morality and social purpose?

Hence the pressing interest of the question, to what extent modern progress in natural knowledge, and more especially the general outcome of that progress in the doctrine of evolution, is competent to help us in the great work of helping one another? (Thomas Huxley, Evolution and Ethics, p. 79 [1895 edn.]; p. 137 [1989 edn.])10

Here is my entirely unauthorized extraction, which I hope is not so unskilled as to draw much fire from the philosophers and historians of science.

Huxley broke with the tradition of viewing evolution as a march of ever more complexity and ever refined achievement. Instead, he describes a breaking down, or simplifying outcome of many processes that approach a more cyclical effect in the long term. It’s not a genuine cycle so much as a frequent tendency toward destruction and loss, an effective simplifying of ecologies, which then serve as a new baseline, creating an illusion of cyclicity. In this, Huxley was right on target, although the history of mass extinctions would not be investigated seriously until over half a century later.

As if that were not enough, he introduced the unsettling consequence, the “baleful product of evolution,” as he calls it, of suffering—raw pain. And in complete disagreement with just about everyone who was currently identified with the questions of evolution and humanity, he said that suffering is not alleviated by evolution, but made worse. Bluntly, life hurts. It is painful and unfair; there is no aspect of existence which imposes justice, harmony, or compensation. Human history did not escape from the bestial struggle into the rarefied halls of human society. It has nothing to do with anything triumphant, transcendent, or indeed, anything good.

There’s a lot of Schophenhauer in there, especially the stark confrontation of the personal experience with the objective, and the simple denial of deep metaphysical understanding from material or, as we see it, real observation and thought. Huxley precisely dismisses chance as the operative factor, describing our history and our current rotten experience as the inevitable outcome of physical causes in succession. He refers to an “eternal immutable principle” of individual effort, later “the instinct of unlimited self-assertion,” which is almost identically to the Will described by Schopenhauer, but goes the famously harsh philosopher one better, in removing metaphysical content from his description and landing us, humans, in an utterly physically determined condition.11

Huxley cited modern, political humanity as the state in which suffering has reached its most acute form. Evolution, natural selection itself, didn’t make a happy animal, merely a very social one. We rather brutally minded creatures now find ourselves in a new social environment, in which our behaviors mainly accomplish abuse and oppression. Far from being an exalted or successful or otherwise perfected being, the human is a generally confused and bloodstained sufferer, with newfound ethics bashed around by long-established avenues of behavior.

For his successful progress, throughout the savage state, man has largely been indebted to those qualities which he shares with the ape and the tiger; his exceptional physical organization; his cunning, his sociability, his curiosity, and his imitativeness; his ruthless and ferocious destructiveness when his anger is roused by opposition.

But, in proportion as men have passed from anarchy to social organization, and in proportion as civilization has grown in worth [he clarifies this later as “ethical” rather than civilized], these deeply ingrained serviceable qualities have become defects. . . . they decline to suit his convenience; and the unwelcome intrusion of these boon companions of his hot youth into the ranged existence of civilized life adds pains and griefs, innumerable and immeasurably great, to those which the cosmic process brings on the mere animal. (Evolution and Ethics, pp. 51–52 [1895 edn.]; pp. 109–110 [1989 edn.])

They used to be ordinary, effective behaviors, but now they generate oppression, evils, crimes, and confusions. Bluntly, human life is especially miserable because evolution has landed us in a situation we aren’t good at. He specifically denies that historical human societies represent stages of social or political development, identifying all recorded human history as in the same boat, which by implication flew in the face of current British claims to reside at the apex of sociopolitical development.

Despite its complete reversal from contemporary narratives, this idea is dated in some ways. It posits a wholly human ethics, however nascent and recent, opposed to a wholly animal past, missing the complex social interactions of many nonhuman species. It hints at Edenism, the idea that prehuman or nonhuman existence was “better matched” to its environment, and therefore happier, or at least it can be read with that underlying implication. The harshest modern reading of evolutionary theory suggests that selection is never about happiness, or that the technical term “fitness” carries no implication of matching or fitting into any appropriate conformation. But this view doesn’t disagree with Huxley so much as specify that even he didn’t go far enough. Updating his essay to modern understanding actually makes his primary points even stronger.

His primary targets were well chosen. He attacked the claim to evolutionary justification made by two groups: activists for reform, who over-idealize humanity’s alleged “rise from the beasts” and expect miracles of justice to appear yesterday; and industrialists and imperialists, who exploit our alleged “brother to the beast” imagery to justify their bullying and exploitation. He tossed out any suggestion that society itself—specifically any distribution of privilege and misery—has evolved or is evolving toward an ideal state. Natural selection has not favored virtue over villainy, or villainy over virtue, however one may define those terms. In this, he accurately demolished current social appropriations of the words evolution, natural selection, and Darwinian, progressive and cynical alike. Human social effort to date, nice or nasty, is simply not the issue—what he sees is the injustice that prevails and our evident difficulty with, as he puts it so well, helping one another. What ethics have developed remain largely potential, in application.

That man, as a ‘political animal,’ is susceptible to a vast amount of improvement, by education, by instruction, and by the application of his intelligence to the adaption of the conditions of life to his higher needs, I entertain not the slightest doubt. But, so long as he remains liable to error, intellectual or moral; so long as he is compelled to be perpetually on guard against the cosmic forces, whose ends are not his ends, without and within himself; so long as he is haunted by inexpugnable memories and hopeless aspirations; as long as the recognition of his intellectual limitations forces him to acknowledge his incapacity to penetrate the mystery of existence; the prospect of untroubled happiness, or of a state which can, even remotely, deserve the title of perfection, appears to me to be as misleading an illusion as was ever dangled before the eyes of poor humanity. And there have been many of them. [from the end of the Prolegomena] (Evolution and Ethics, pp. 44–45 [1895 edn.]; pp. 102–103 [1989 edn.])

Intellectually, this concept is a tour de force of beauty and horror, as it rightly recovers biology from its appropriation by all political efforts. Human exceptionalism is denied both its self-congratulatory rise from beast to angel and also its wallowing in exploitation, racism, and war with the excuse of being mere beasts.

He also broke with the metaphysical or spiritual model of human goodness, which at this time was generally comfortable with the idea that religion represents the highest and most fulfilling mode of human contemplation. Instead, he identifies the primary value in religious practice in the ascetic doctrines from some Hellenic philosophy, Buddhism, Hinduism, and some elements of Christianity—to recognize the complete failure of life to award contentment. This idea also ties into Schopenhauer’s ideas, in On Religion and especially in The World as Will and Representation (volume II), regarding those practices. It’s also a little unusual for Huxley in that he isn’t kicking organized religion in the shins with metal-tipped boots, but rather acknowledging a certain sense in these practices. That’s probably because he’s talking about individual contemplation and choices about engagement with the world, rather than institutions of power and their doctrinal claims.

In earlier writings, Huxley had been gentler or more optimistic. He had always granted that rationality and, specifically, speech, illustrate an existing status for humans that transcends our primate origins. He had implied that people receive a vague karmic compensation during the course of their lives, or claimed that the new standards of scientific thinking had already begun to usher in an age of human happiness. Here, forget it: no such tangible goodness is evident. Our experience is an animal one, because it is experienced by animals, and it’s arguably a particularly bad one. Huxley’s portrait is doubly chilling given his simple, undemonstrative description—somehow, as a reader, I get that he really, really means it.

In a word, Evolution and Ethics was a huge stink bomb tossed into the parlor of human self-congratulation. All the established interpretations of evolution and humanity had been comfortably distributed across the political landscape, each appropriating the terms to consider itself the most evolved. It was still all about privilege and claim to authority, with “scientific” as the new “divine” justification for power. Huxley was having none of it.

However, at the end, his conclusion lapses back into his ideals. In some contradiction to his claim that older cultures were no less mentally astute than modern ones, he posits a social-scientific solution, as yet undreamed of, in the future:

Let us understand, once and for all, that the ethical progress of society depends, not on imitating the cosmic process, still less in running away from it, but in combating it. It may seem an audacious proposal thus to pit the microcosm against the macrocosm and to set man to subdue nature to his higher ends; but I venture to think that the great intellectual difference between the ancient times with which we have been occupied and our day, lies in the solid foundation we have acquired for the hope that such an enterprise may meet with a certain measure of success.

. . . the highly organized and developed sciences and arts of the present day have endowed man with a command over the course of non-human nature greater than that once attributed to the magicians. The most impressive, I might say startling, of those changes have been brought about in the course of the past two centuries; while a right comprehension of the process of life and of the means of influencing its manifestations is only just dawning upon us . . . [in reference to astronomy, physics, and chemistry]. Physiology, Psychology, Ethics, Political Science, must submit to the same ordeal. Yet it seems to me irrational to doubt that, at no distant period, they will work as great a revolution in the sphere of practice.

. . . it would be folly to imagine that a few centuries will suffice to subdue its masterfulness to purely ethical ends. Ethical nature may count upon having to reckon with a tenacious and powerful enemy as long as the world lasts. But on the other hand, I see no limit to the extent to which intelligence and will, guided by sound principles of investigation, and organized in common effort, may modify the conditions of existence, for a period longer than that now covered by history. And much may be done to change the nature of man himself. The intelligence which has converted the brother of the wolf into the faithful guardian of the flock ought to be able to do something towards curbing the instincts of savagery in civilized man. (Evolution and Ethics, pp. 83–85[1895 edn.]; pp. 141–143 [1989 edn.])

His language is tentative: he hopes for a certain measure of success, with hints of social practices or even a re-engineering, which ought to result in a behavioral and ethical human profile with more generally happy results. For something that is “irrational to doubt,” it’s distinctly iffy. My reading is that these final passages do not stand up as argument, but as hope—perhaps a little desperate, at that.

Even Huxley—the man who in Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature had publicly demonstrated that humans are apes—couldn’t escape the dichotomy between “humans are no beasts,” which caricatures humans into quasi-angels, versus “humans are mere beasts,” which caricatures nonhumans into selfish savagery. Even casting our real selves into the latter doesn’t do it, because the former is still out there to be discovered. His proposal tries to escape the zero-sum between these imagined “beings” by introducing time: currently, we are effectively not civilized because we are beasts; later, we will not be beasts because we will be civilized. But since the two images remain, Man and Beast as ever, his construct yet retains an indigestible combination of a lowly beast not advancing with a glowing if vague notion of what advancing to true humanity would be (Figure 1.6). The new and actual human experience, waiting in the future, gift-wrapped in all his uncertain words, is still special and exalted as ever.

Figure 1.6 Evolution and Ethics exceptionalism.

Human exceptionalism had become a trap, and it held shut into the twentieth century, despite the evidence already described, and in the continued face of all evidence to come. Huxley’s peers generally dismissed Evolution and Ethics or regarded it as a personal lapse, leaving the distorted versions of evolution intact. In literature, the conundrum underlies the work of the next two generations of Huxleys, but I want to focus on someone else, who did not fear to take the lecture’s strongest argument all the way.

Just as Lawrence’s lectures were dramatized by Shelly at the conception of modern biology in the early 1800s, so Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics was dramatized by Herbert George Wells. Whether he was in fact present at Huxley’s lecture isn’t known, but he clearly knew it or the later publication backward and forward. Wells was perfectly placed to comment on these issues. He was in his late twenties, barely finished with his studies in zoology, during which time he’d been a student of Huxley’s, and had been a teacher but was not a practicing scientist. He was also a social activist, although a contentious one and not easily associated with a specific group. His career as an author was recently launched with some essays, short stories, and two books, including The Time Machine. He and a few other authors were discovering that speculative fiction could provide a unique and exciting critique of science, values, and society.12

This remarkable confluence of all the current questions in one thoughtful, creative young man found its voice in The Island of Doctor Moreau, published in 1896. It’s inspired by and deeply rooted in Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, but—just as with the 1818 Frankenstein’s roots in Lawrence’s lectures—not to rail against it, but as an informed reflection on the most difficult points that had been raised. Just as Frankenstein is not about a feeble-minded, zombified brute, The Island of Doctor Moreau is not about the lurking or erupting threat of animalistic savages. Moreau succeeds in his project; his creations are human persons who experience their lives just as we do. The story is instead about what we are like, and the myriad means by which we refuse to see it.

Historically, it captures a moment in the intellectual crisis between biology and the accustomed modes of thought and status. Moreover, it presents the questions as they still need to be asked, free of institutional wrangling and identity politics.

•What is our basis or founding principle for how to treat nonhuman animals?

•Where do our ethics come from, anyway?

•And underlying each of these: What does our status as a zoological animal mean regarding human society, and does it matter?

True to its source, it is also one of the least sentimental novels available, in which its action and butcher-shop horror are not exciting so much as disturbing, wince-inducing, and outright grievous. It is about animal suffering, explicitly including our own. It adds up to the question that drove Evolution and Ethics despite its hint of hope: Who are we?

The story is similar to Frankenstein in some ways. The scientist, Doctor Moreau, succeeds in creating humans from animals, but interprets the results as failure, and the narrating character, Prendick, recoils from his own understanding of their humanity. In line with the adaptations, Moreau has a subordinated assistant, too, named Montgomery. Its structure is more organized, however (Figure 1.7). Moreau and Montgomery have little or no character arcs at all, so their roles are limited to portraits and then to what their prior decisions and attitudes have brought them. Moreau is physically and intellectually a massive force, certain, unswerving, self-assured, and despite one significant frustration, at peace with himself and his project, whereas Montgomery is depressed, alcoholic, and belligerent, yet connects better with the created people partly out of sheer loneliness. Prendick is the dynamic character, whose knowledge of the situations increases in ways not accessible to the others, and his attitude toward those situation changes several times. He’s not a narrator “eye” at all, but takes decisive action more than once. Overtly, it’s much more his story than theirs.

Figure 1.7 Diagram of the plot, The Island of Dr. Moreau.

The outer frame is about Prendick being frightened of humans, specifically of seeing what one calls the animal in them. In Chapters 1–3, that means several grim situations, beginning with the temptation and threat of cannibalism, then bullying and cruelty, including being abandoned to die on a raft twice. In Chapter 22, when Prendick is back in England, his fear is much more profound: he can’t stand being around ordinary humans doing ordinary things, seeing the animal in every face, every action, and every intellectual, social, and religious endeavor.

The inner frame is about his time on the island, interacting with Moreau’s creations, called the Beast Folk. He goes through several phases, first thinking they’re humans bestialized by surgery and fearing to share their fate, then, after learning their origins, struggling with different degrees of empathy, and finally descending into terror and hatred. This final full recoil is subtle, because Prendick is a little bonkers at this point. Briefly, despite his fervid imaginings, the Beast Folk never “revert to the beast” in the sense he imagines, that is, there is no final grunting rampage of violence. Instead, first he can’t stand being around the Beast Folk doing ordinary human things, and is then further traumatized when they rather quietly and sadly revert to their original forms. There’s plenty of violence in the story—both of the other human characters, Moreau and his assistant Montgomery, meet their ends at the hands of Beast Folk—but it’s never actually the berserk “reverted beast released” that’s responsible.

Given the complex series of thoughts and emotions in the inner frame, the effect of the final chapter is a remarkable blow—right at the height of Prendick’s hatred and terror of the Beast Folk for being too much like people, the story brings him off the island and into his stunned horror at ordinary people, for being too much like animals. In particular, Huxley’s purported golden era, somewhere beyond the horizon, in which better-natured humans suffer less in a better society, is nowhere to be found.

In Frankenstein, the created man gets his say at two points, with plenty of time to make his points to a committed listener. In The Island of Doctor Moreau, the Beast People are no less present and active with their own thoughts and decisions, but they are voiceless in comparison. The four most important barely get the chance to talk at all. Still, enough information is given to work with, more subtly, in order to see what the story is like for them. Despite Prendick being the narrator, I suggest that these characters comprise a shadow-novel of their own.

The structure and the tacit stories are pretty easy to see once one puts aside preconceptions and reads the words with a certain suspicion toward Prendick’s narration. Similarly to Victor Frankenstein, his delivery doesn’t always accord with what he describes. He develops a considerable fear of the Beast Folks’ innate or imminent savagery, for example, but the actual violence and outright malevolence they exhibit is less than that evidenced by the human characters, including himself. The imagery is similarly blurred by what he only hints at or leaves out, and especially by subsequent visual media, which fill in the gaps with material that simply is not part of the book’s content.

I don’t expect anyone to accept my interpretation at this moment of reading. The novel has been culturally and academically smeared as gaudy and superficial, and it’s been thematically reversed, even worse than Frankenstein was. Everyone “knows” the Beast Folk are hairy animal-headed monsters, that Moreau is a barking mad sadist, and that it all ends in a rampaging conflagration in which they punish him; that the book is only and ever about how out-of-control scientists do crazy and hurtful things, torturing animals and making monsters who are simultaneously victims and mortal threats to the rest of us. I happen to think it’s not, but there’s no reason that you should trust me about it. I only ask for a new, close, and thoughtful reading, which I’ve tried to support by writing this book.

I’ve done that because the intellectual and ethical crisis of human exceptionalism was not resolved in the 1890s. The two social-appropriation distortions of evolution remained. The range of Huxley’s and Darwin’s actual work remains underappreciated, as opposed to their public lives or the single concept of natural selection. Evolution and Ethics effectively failed, leaving behind only its finishing glimpse at utopia, when it might have gone even further in examining the human animal. The political crisis of animal care in research was socially set in place with no grounds for resolution (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Timeline of human exceptionalism.

Rather horribly, this exact lack of resolution became the “new normal” and has only been grown layered with new details and more contorted for over a century. Biology itself remains schizophrenic about humanity, not yet daring to fold psychology into animal behavior or anthropology into mammalogy. Every other discipline firewalls biology away from it, sometimes with great fear. Ethics and policy regarding nonhuman animals, despite some gains, remain barely coherent. Education, legislation, and practices concerning our biological identity have twisted and turned, but the underlying exceptionalism remains fixed. The Island of Doctor Moreau was not only the most informed and challenging book of its time, but it is still the single most relevant and provocative book about these issues for our time, because it throws the still-unresolved crux of human identity and exceptionalism for these precise controversies into plain sight.

My primary reference is obviously Marilyn Butler, Frankenstein and Radical Science (1993), which is the title for her introduction to current reprints of the 1818 version of the novel, and also her Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries: English Literature and Its Background, 1760–1830 (1998). Making Humans (2003), edited by Judith Wilt, includes the 1818 version and Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, but does not include Butler’s analysis and does not mention Lawrence.

Mary Shelley was a literary genius, and fortunately many reviews are available. Useful biographies include Anne K. Mellor, Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, and Her Monsters (1989); Joan Kane Nichols, Mary Shelley: Frankenstein’s Creator (1998); Miranda Seymour, Mary Shelley (2011); Dorothy Hoobler and Theodore Hoobler, The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein (2007); Muriel Spark, Mary Shelley: A Biography (1987); and Roseanne Montillo, The Lady and Her Monsters (2013).

I’ve used the Princeton University Press version of T. H. Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, published in 1989, including James Peralis’s essay on its historical context and George C. Williams’s discussion of human behavior and evolutionary theory. Useful biographies include Adrian Desmond, Huxley: From Devil’s Disciple to Evolution’s High Priest (1994); Paul White, Thomas Huxley: Making the “Man of Science” (2002); and Sherrie L. Lyons, Thomas Huxley: The Evolution of a Scientist (1999). An account of his views of humanity is included in Misia Landau’s Narratives in Human Evolution (1991) in comparison with Darwin’s and Haeckel’s.

Bruce Moran’s Distilling Knowledge (2006) provides an accessible history of chemistry as context for reading William Lawrence, Lectures on the Physiology, Zoology, and the Natural History of Man, delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons (3rd edition, 1823).

I’ve used the 1996 Dover Thrift edition of The Island of Doctor Moreau, which is an unabridged reprint of the original 1896 publication by William Heinemann, London.

There are too many biographies and reviews of Wells to cite completely. A good start includes Norman and Jean MacKenzie, H G Wells (1973), which is especially helpful regarding his influence by Huxley; Vincent Brome, H G Wells: A Biography (1951); and Michael Sherborne, H. G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (2010).

1.The term “materialism” has undergone many twists and turns of meaning. In 1810–1830, relative to Lawrence, I’ve found it better to use “material” for the adjective, to indicate strict physical causes, rather than the technically correct “materialist,” given the implications developed later for that phrasing.

2.William Lawrence, Lectures on Physiology, Zoology, and Natural History of Man, 1823, published by James Smith (available at https://archive.org/details/lecturesonphysio00lawrrich).

3.Two other difficult terms are “abiogenesis” and “biogenesis,” which at first meant what they sound like, with the former indicating a chemical underpinning to life. However, they flipped or reversed meanings later in the nineteenth century, relative to the debates of whether living things were produced de novo from nonliving material or from other living things. It was difficult to address the question, if life is nonvitalist (no super-added forces), then why it only emerged from other living things, and these terms twisted quite a bit in the winds of that discussion.

4.The three formal components of cell theory are that living things are composed of one or more cells, that cells are the smallest unit of life, and that cells arise from prior cells. Neither Antonie van Leeuwenhoek nor Robert Hooke discovered cells in terms of this understanding. They looked at them, and named them as things they saw, which is very important but isn’t to the point. Cell theory begins intellectually with Lawrence, then booms with Schleiden, Schwann, Pasteur, and others, including Huxley’s “primordial fluid.” Biology is no less guilty than other disciplines in wanting to backdate its modern content further than it should.

5.Much of Lawrence’s text about humans is ethnically tagged and includes racist concepts and terms. Appalling as this is, I think it does not interfere with many of his points when they are applied, as they do, to every human being.

6.Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, second edition, 1887, translated by Walter Kaufmann, published by Vintage Books, 1974.

7.The chronology of Frankenstein publication is tortuous: the first version was published anonymously in two or more short volumes (a common presentation at the time) on January 1, 1818; then the stage play Presumption: the Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinsley Peake was presented within a year or two. In the play, the creation is mute and infantile; Frankenstein has a comedic assistant named Fritz; and Frankenstein collapses in shame, remorseful of his “impious labor.” I suspect the play and similar productions were a constant feature throughout the nineteenth century, contributing to later film tropes. The novel was then republished in 1822 under Shelly’s name with emendations by her father, again in short volumes. Its 1831 publication puts the whole story between two covers for the first time, including the revisions and additions as described by Butler.

Both Lawrence and Shelley succumbed to social pressure, but one should remember the terrible fate awaiting Victorian families, especially women, once targeted for ostracism.

8.Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, The 1818 Text, published by Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 1994.

9.Robert Chambers, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, 1844, published by John Churchill (available at https://archive.org/details/vestigesofnatura00unse).

10.Thomas Huxley, Evolution and Ethics, 1895, published by Princeton University Press, 1989.

11.In The Devil’s Dictionary (1911), Ambrose Bierce defines accident as “an inevitable occurrence due to the action of immutable natural laws,” which seems admirably suited to Huxley’s explanation of the history of life and specifically the origins and current status of humans.

12.Harlan Ellison suggested the term “speculative fiction” to replace “science fiction” and its abbreviations, like “sci-fi,” and it fits well here.