The Ape Man can never be truly Man, can he? He gets so excited about big ideas and abstractions, he can’t stop talking about them and wanting others to join him. He says this stuff is important; he wants it to be important even when it takes him into silly spirals. He’s the talkative, geeky intellectual of the Beast Folk, and he probably annoys most of them even worse than he does Prendick, who never affords him an ounce of respect.

I have no claim to better mental processing than the Ape Man, and my conclusions may be as easily mocked or manipulated. But like him, all I can do is try.

People have asked me, what’s your book about? Technically, human exceptionalism. Historically, evolutionary biology and literature. But emotionally, I have found, it is about pain. Certainly and not trivially, the plot events of the novel are driven by the pain of bodily harm. This is most dramatically the pain inflicted on nonhuman animals during most of the history of live animal experimentation, and—as Moreau misses completely—it isn’t solely about specific receptors in the skin, but rather the pain of helplessness, of fear, and of despair. Pain under torture is the issue. The immediate moral question is how much of this we intend to inflict on others. The bigger look is whether all life is helpless enough to be considered pain under torture. That may sound a little adolescent and melodramatic, but hold that thought for a moment.

Yet the novel also touches on the pain of being alone. When Prendick and the Hyena-Swine face one another on the beach, which I now see as the climax of the story, each is as alone as a person can be: sympathetically speaking, each is alienated from his culture, unable to regard its norms as a cosmic good; and also at his most repellent, each is potentially willing to be a cannibal. Their respective internal solitudes are the same, denied even the most basic metaphysical narrative, the one that says to you, “You are special.”

What’s worse, each of them hits every one of these buttons for the other. To each, the other is truly the Other—a presence whose perception and judgment cannot be controlled. Here, the terms from psychology, philosophy, and biology link up flawlessly: to our kind of ultrasocial animal, it is nearly intolerable that someone is looking at me in a way different from how I look at myself, and yet he or she has the temerity actually to be in the real world just the way I am. This moment is when we connect or we reject. In a world-experience lacking metaphysics, that becomes the only real question: when confronted by the Other, whether one feels exposed, isolated, foolish, targeted, and more alone than ever; or illuminated, given context, provided with listening, and no longer alone.

If being a beast rather than a human meant no management over inflicting pain, no power to act against being inflicted with pain, uncontrolled aggression, randomly directed violence, predation arising from fury, eating of whatever presented itself (including one’s fellows’ bodies)—and if this were a beast’s “place,” its identity, such that elevating it to the rational state of Man could not help but fail—the “don’t meddle” story would be so easy. It would look like this:

•Conversion into human anatomy and cognition (Man)

•Management and responsibility of inflicting pain

•Reversion into the original animal forms (Beast)

•Unmanaged aggression and violence

But in this story, these components don’t lie down neatly into that dichotomized package. Instead, they are all present but curiously isolated from one another, overlapping in different ways and at different points. Their associations are cast into less comfortable forms: Moreau, in his idea of the rational Man, denying his responsibility to consider others’ pain and therefore inflicting it to an unutterable degree; Montgomery, with his predilection for bad-tempered deadly force; Prendick, constantly fearful the Beast Folk will rend his flesh, while being the only character who really knows what it means to choose to eat another person.

Instead of the compartmentalized breakdown, you get an overlapping mess, which destroys the Beast + Violent + Cannibal/Man + Civil + Virtuous compartments. This isn’t an interpretation or an impression or a symbol; confronting you with the mess is what the story does. Instead of “don’t meddle,” it’s the “reality slap” story. Forget it, “Man.” You aren’t what you thought, you aren’t who you thought, and in fact, it’s not even about you. The real manager of violence in the story is M’Ling. The real moral voice regarding pain is the Puma Woman’s.

A “don’t meddle” story may have thrills and chills, but ultimately it’s comforting. This one isn’t. It shocks, it confronts, it prompts deflective interpretations that immediately deny the text, and it prompts revisions that alter its content into palatable forms and culturally silence it.

Why has this novel received such a strong recoil? Because if you experience the “reality slap,” then you’re no longer the hero of the Story of Man, whatever that might be for you. You’re a Beast Man or Woman, standing in the Valley. There is no arc cresting in you or a shining goal you may point toward. Nothing in the universe or its processes protects you from crushing agony or death. All you have, and really nothing more, is that like any creature anywhere, you’re at least undeniably here for a while—and after the shock, maybe that’s enough. It’s not nothing, literally. We’re something, we’re someone, grubby and brief as it might be, and we might think about working something out together, even if there’s nothing so very grand about the task.

The story includes blank spots, apparent only because Prendick sees some hint of things going on outside his perception, or a late moment in a sequence of events. I’m not talking about the narrator of the story telling us an out-and-out lie. This isn’t a puzzle or a guessing game. Instead, the narration accords strictly with Prendick’s outlook and assumptions, but the events show how limited those are, therefore forcing the reader’s participation in the story’s content.

•Did the Puma Woman secretly weaken her chain in planning her escape?

•Did Prendick have sex with a Beast Woman?

•Did the Sayer of the Law act upon his oath to uphold the new Law when he killed Montgomery, whom he had just seen threaten Prendick?

•Was the Hyena-Swine sneaking up on Prendick on the beach, or trying to talk to him?

The “found document” technique isn’t merely a quirk, but literally makes you, the reader, decide “yes” or “no” to these things. It’s perhaps the most confrontational feature of the novel and, technically speaking, closes the Man/Beast divide with some force.

That brings the discussion straight to Arthur Schopenhauer, and why I decided to hook the sections of the book together with him. Believe me, I held back (you can mine this guy for quotes all day):

Nothing leads more definitely to a recognition of the identity of the essential nature in animal and human phenomena than a study of zoology and anatomy. (Arthur Schopenhauer, “A Critique of Kant,” On the Basis of Morality, p. 233)1

I don’t think Schopenhauer’s writings are a recognized school of thought with a codified set of precepts, and even if they were, I’m not interested in the traditional philosophical model of a worldview or a construct to adhere to. Instead, Schopenhauer interests me because he breaks with—and in fact completely leaves behind—the idea of cosmology as a moral directive. The cosmos provides no spiritual or logical guidance, and instead is imbued with the Will—the unexplained and quite unstoppable, defining drive of doing things. Today, I’d talk about this as a feature of thermodynamics, but that doesn’t really matter—the idea is that natural forces are amoral and overwhelming, and our own behaviors, drives, and perspectives are local examples.

That’s an important point, that Schopenhauer’s Will is not merely a fun little celebration of human desire. It’s not about saying, “I want a pony,” and making that happen. It means that any drive, any sense of achievement or purpose—family love, community or national identity, a political end—is as amoral and potentially full of destruction and suffering as anything else. It’s ultimately saying that our sincere sensation of purpose is not the same as having purpose. It’s not discoverable through logic, through investigation of the physical world, or through an ideal. Really, you’re just “here.”

In practice, to the extent that ethical suggestions are even present, these notions fall back on simple daily compassion and trying to muddle through the day without letting your drives sucker you into cruelty or misery, with no concern for a grand design to bask in or to seek.

This trajectory of thought didn’t connect with scientific views very much at the time, which is why seeing Schopenhauer so explicitly in Evolution and Ethics is a bit surprising, especially since he’s uncredited in what’s otherwise a very well-referenced work. One might do worse than to trace intellectual consistencies from David Hume’s writings through various pre- or proto-evolutionary thinkers like La Mettrie, then Lawrence of course, through Schopenhauer’s body of work, pulling apart the Vestiges to see which ways it zigged and zagged, through Huxley’s and Darwin’s extensive work on anatomy and behavior, Huxley’s biography of Hume, Nietzsche’s The Gay Science among others, and, via Evolution and Ethics, finally into the renewed debates about human behavioral ecology beginning in the 1980s—particularly how badly they’ve floundered.

Such a project would uncover a surprising idea about human ethics: that I might prefer to be an “earthy” animal, in Nietzsche’s terms, subject to physicality and history, in the absence of natural law, who can at least try to arrive at less suffering among us, than a higher Man. That higher Man hasn’t done very well for us; he seems defined by his empowerment to inflict suffering or, upon being demoted, forced to receive it at another’s whim. Maybe after all the pretty talk is past, that’s what the higher Man really is: the Master of the House of Pain.

What happened to philosophy might be known to other historians and scholars, but it’s a mystery to me. All I know is that after about 1900, the discipline’s prior connection with natural history evaporated. It has a terrible relationship with nature, which stubbornly refuses to be either a deontological principle or a utilitarian end, and, as far as I can tell, seems to focus strictly on either metaphysics or a disembodied and over-rationalized form of ethics. The twentieth-century extension of Kierkegaard and others, existentialism, went off on its own road with a spiritual notion of personal free will that maintained nothing of Schopenhauer’s concept.

I could be missing the boat regarding the most famous philosophers of science, Karl Popper and C. P. Snow, but with all respect to them, their works are over-concerned with epistemology and not enough with content. I don’t see that they had much direct contact with science in action or, in Snow’s case, at least not much nuts and bolts biology.

As I’ve encountered it, the philosophical (and eventually others’) rejection of science is based on a series of apparently deliberate mistakes, in a specific order.

•First, that reductive causes, or small things making big ones happen, are considered more important than—here a word is lacking—the reverse, with big things making small ones happen. Biologists study both and always have.

•Second, reductive cause is confounded with, or smeared as, reduction-ism, the idea that larger-scale phenomena are deprived of their identity or scale-specific properties if their reductive causes are identified.

•Third, reductionism is confounded with atomism, the idea that a phenomenon’s features can be identified in full in each of its tiny subunits (genes are particularly vulnerable to this misunderstanding).

•Finally, and most toxic of all, plain and simple material thinking is identified with this weird construct of reductionism + atomism. Therefore to call for a scientific understanding of humans is instantly derided as essentialist, the claim that one is reducing the identity of humans into mindless little particles. It’s not much different from Abernethy’s outrage at Lawrence, merely given an intellectual gloss if you don’t mind the errors.

Scientific inquiry is guilty of none of these things, but it did itself no favor internally either. The new social environment of science is riddled with awful, senseless dichotomies, of which the mindless/brainless distinction is a mere echo. These dichotomies—instinct/learning, genetic/environment, nature/culture—are present in force throughout science and non-science, tripping up every effort to link across those disciplines. They’re perpetuated and reinforced by obfuscating terminology, maintaining the Man/Beast dichotomy at every turn, such that complex and/or social behavior in nonhumans is “instinct” even when it includes learning, memory, and emotions, whereas even simple behavior in humans is “conscious.”

The reluctance has always remained in the bedrock of modern biology, systematics. Linnaeus’s thoughts on humans and the other apes were confirmed by Huxley in the 1860s, but the muted, misleading classification was never revised to reflect his work. In George Gaylord Simpson’s great taxonomic revision of mammals in 1945, there it was again: Homo sapiens by itself, way over in a family called Anthropodidae, with the other great apes racked together against all anatomical logic in Simidae. When data from mitochondrial DNA finally made this false construct too absurd to ignore in the 1980s, it was wrongly billed, even by biologists, as overturning earlier anatomical work, when it actually confirmed and refined what Huxley had shown over a century before.

That was no exception, far from it. It’s still like pulling teeth to acknowledge that the orangutan, gorilla, chimpanzee, and human, along with their extinct related species, comprise a single taxonomic family, let alone to debate its name or to address the unnecessary over-nominalizing within it into tribes and superfamilies and subfamilies.

I could kick some shins regarding professionalism in the sciences, too, in how what began as an unconstructed set of grassroots journals become a starchy, risk-aversive, and cloistered activity subordinate to publications, reputations, promotion, and tenure, and effective servitude to university administrations through the financial mechanisms of grants. A certain tension has always existed in scientific education between the implications of (i) professional skill and employment and (ii) specialization and segregation from other branches of knowledge, and it’s long overdue for some historical scrutiny.

Academe as a whole went ahead and firewalled the whole damn thing from ourselves, as well, mainly through disciplinary boundaries: psychologists get the mind, physical anthropologists get the body form and evolution, cultural and social anthropologists get the habits and actions, biologists (or rather, medical physiologists) get the diseases and pathologies, historians get the documentation. These boundaries are not minor—they define job success and the unspoken standards of content for scientific publishing, and quickly became perceived as intrinsic; to be a scientist at all, one had to internalize the standards within each one, separately.

I’m sad to say that both modern science and academia in general are practically defined by coping mechanisms to avoid being scientific: all those trappings of shiny science, safe in its segregated fancy buildings; all those nice “-sciences” appended to the department names; and little to none of the thinking that throws open doors across the established disciplines, prompts the sharpest of personal and political reflection, and holds every claim made by anyone to the fire of making sense. We see no Lawrences today—there’s a dedicated social system in place to make sure of it.

By the mid-twentieth century, real scientific inquiry wouldn’t touch humanity with a ten-foot pole. Dialogue is belittled by appeals to consciousness, to metaphysics, to recent details like industrialization, to the dubious honor of overpopulation, to flat-out untruths, and to disciplinary constructs and constraints. It’s especially disheartening to encounter how badly biology has been demonized in the social sciences as ethically and politically bankrupt. I see there an outright flat refusal of psychology, sociology, economics, and a significant component of anthropology to make Lawrence’s and Darwin’s jump. Instead, there’s a sprayed fog of claims that we are “unlike the animals,” or deceptively, “unlike the other animals,” and “from the animals but” followed by a false claim. I see hardly a shred of thought toward economics as a subset of ecology, sociology as a subset of behavioral ecology, and psychology as a subset of developmental psychobiology. Instead, those are supposed to be something else, the latest word for that separate high status for humans: culture.

The word from sociology is that biology denies culture. I don’t know where they get that, but there it is. Let’s see what happens when I look at human culture with Prendick’s gaze, but unlike him, without fear. What happens, how terrible is it, to look at the human species just as one looks at a species of gopher?

•It has a phylogenetic and species identity, expressed as a distinct set of developmental events.

•It has an ecological context composed of abilities and constraints.

•It has an identifiable range of behavior and socializing.

•It has regional variants regarding fairly trivial details and a considerable amount of gene flow.

For any and every species, the biologist expects these topics to be integrated and coherent, with acceptable results being in part defined by consistency across different analyses. He or she knows that any of these topics might boom into a rich and nuanced array of history and surprising properties. We’re supposed to debate how they work in order to enrich, expand, and revise all possible connections and understanding.

Here, I see a relict species of bipedal ape with its own profile of reproductive, cognitive, and social features; specifically, it records what it communicates—and look, look at what this ape is doing! Briefly, these creatures communicate with abstractions, and they record their communications—then, the recordings become a learning environment for a new generation. The information, values, standards, and vocabulary for a given location therefore become a distinctive spin, reflecting the history there. So, I see culture, always proliferating and changing, always arriving as a distortion of the past and always affected unexpectedly by what happens next. All right, that’s not controversial, it’s an observation. No one is going to take that away.

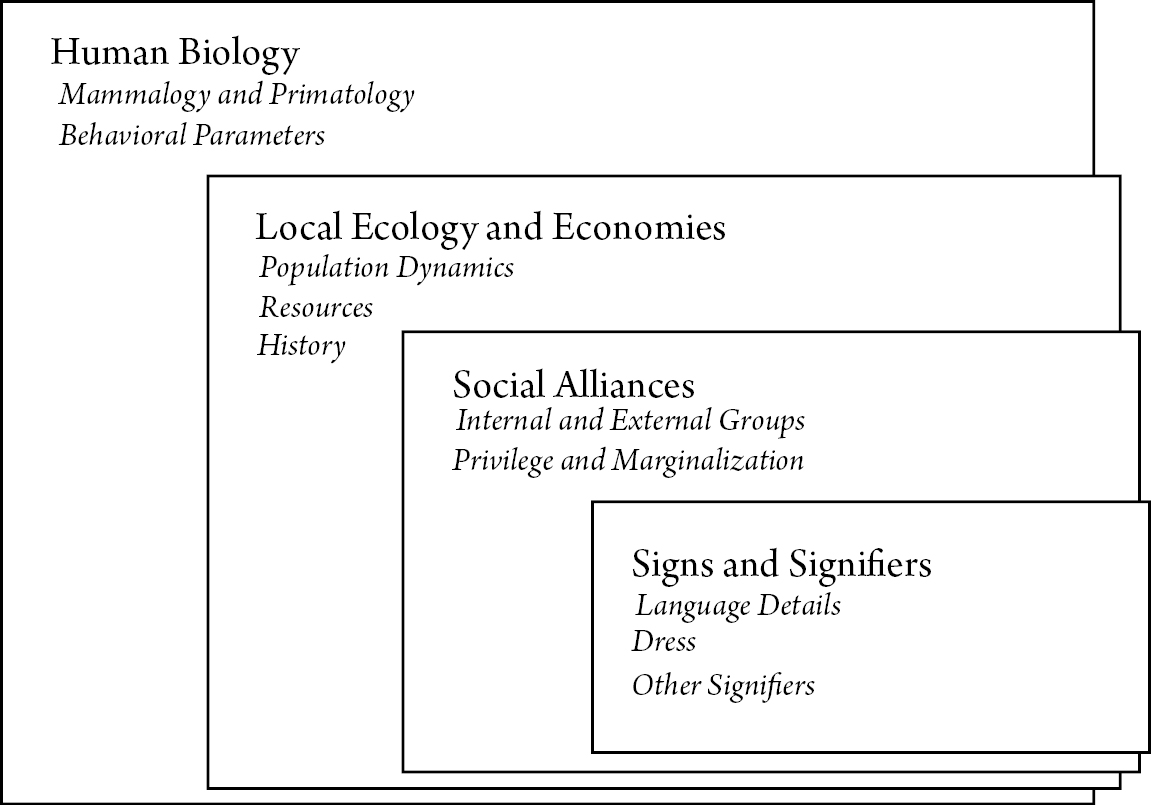

Here’s how it works (Figure 10.1). The biological animal in a given place has all the usual features: a life-history strategy, a set of behavioral parameters, a population size, a resource base with specific geographic properties, and any number of details like local parasites. Given its abilities with social organizing and symbolic communication, various subcultures of effort, exchange, and recompense are operating there, however contentiously and with however much pain and exploitation; these operations and their history are absolutely the historical products of the creature’s biology, including cognition, in this place. These social arrangements become themselves an operating environment, learned and experienced as rock-solid identities and tensions, reinforced through education, but also subject to revision and upheaval as conditions in the underlying power and resources change. These identities and tensions are made explicit through local terms and symbols, in every means of expression.

Figure 10.1 Human cultural biology or biological culture, as you prefer.

It’s clear, sensible, and easy. I haven’t dented or devalued anything concrete stated by any of these other disciplines, I haven’t said they’re “nothing but” biology, and I haven’t said that we as humans don’t do those things. The only thing that’s added is to expect that these different levels make sense relative to one another, such that no set of physical rules gets to be magically isolated from any others. The only things now missing are presumed elevated functionality, special history composed of heroic narrative elements, intrinsically admirable achievements, and a presumed destiny.

The past couple of centuries have brought some new details: industrial technology and notable population abundance, currently undergoing exponential growth. All right, that can be a new topic, and maybe this construct can help us change dilemmas into questions.

I have no intention of trying to argue anyone out of the Man/Beast divide—it is a very deeply felt, unexamined thing, and there’s literally no way anyone will be dislodged from his or her side of it through confrontation. I’m here to talk about what it’s like to see no categorical difference between humans and nonhumans at all, using the term “animal” to mean both, and significantly, seeing absolutely no implications concerning ethical or social capabilities by using that word. My criticism is that this viewpoint, although present and identifiable in individuals like myself, has no general cultural voice. It died on the vine right around 1900, even in the sciences, and therefore has failed to develop any philosophical, ethical, political, or artistic identity for over a century. We need to recognize that failure, to identify its origins, and effectively, to call it out.

Specifically: if you find yourself, like me, unable to identify any fundamental distinction between humans and all other animals, and if you are similarly baffled by the implications so deeply felt by others, then the question for us must be, “What ethics do you stand by, and where do they come from?” And again less formally, “Well, then, who do you think you are?” Furthermore, these questions are not merely individual curiosities, but must be extended outward, socially, intellectually, and politically, to their applications in society, whatever those may be.

Huxley thought he knew, or at least he phrased it optimistically in the last few minutes of his talk. Scientific context and new ethical thinking would bring us around, to solve it somehow or to save us, in the 1890s or by a century later, to blossom into a way actually to live among one another. He was praising the gains in understanding in astronomy, physics, and chemistry, using them as a model for what these other disciplines may become. “Physiology, Psychology, Ethics, Political Science must submit to the same ordeal” (Evolution and Ethics, p. 84 in original; p. 142 in Princeton University Press edn.). This was his key to arriving at a more just society, his “great work of helping one another” in the constant negative context of a grim history and array of easily tapped grim behaviors.

Boy, was he ever wrong on that one. Astronomy, physics, and chemistry arrived all right, transforming the world into a war ecology and war economy, with a global impact on ecology best described as disastrous. The disciplines he hoped to see develop have become methods of political control beyond anyone’s imaginings.

Was Huxley even theoretically right? One would have to admit to a century of dedicated “not quite there yet,” an unstopping reiteration of the 1890s and 19-oughts—the same peripheral imperial assault on the central empire of Eurasia, the same extraction from all economies to support it, the framework of the Boer War, the opium trade, the destruction of the Ottoman Empire, all still in place, repeated in new places, and elaborated upon with more propaganda, more atrocity, and more cumulative misery, like a horrific Mandelbrot’s snowflake. I may be a pessimist, but I’m inclined to say that Huxley’s future ethical developments, the ones he said would be “irrational to doubt,” aren’t coming.

Is there a morality to discover? Can some perspective on the biological human, however battered and dismembered, be recovered enough even to see whether it helps us, as he put it, help one another? Maybe, if by “morality” we mean common ground for discussion, a context rather than a directive. Maybe, if we can keep biology from becoming a cosmology, a story in which we hold the starring role. Maybe, if we can grasp that basic ethics does not translate easily into sustained policy. Maybe, if the idea is more like building a bridge in the knowledge of Newtonian physics, and understanding that we might not be very good at it, and it’s a work in progress. Maybe, if we don’t succumb to the Naturalistic Fallacy of saying “what’s biological is right” or—in the lack of a name for it—the corresponding Humanistic Fallacy of claiming culture and policy exist free-floating from our biology. And finally, maybe if we can decide that nothing about morality or an ethos is about making anyone happy, but about reducing misery, that it works not because everyone is satisfied but because we have some agreed-upon idea of what shows we’re better off than we were.

And after that, I want a pony.

All that is too heady for me, even in Ape Man mode. This was a book about a book, and staying down in that scope, it turns out that over the years, science fiction—or speculative fiction—has plenty to offer in its confrontational mode. When I was in college in the 1980s, professors reacted to the suggestion that “genre fiction” had something to offer with contempt, even nausea. Times have changed, though, and some room has been made after all. Two references that could form the basis for a whole new subdiscipline along these lines include Jonathan Gottschall’s The Storytelling Animal (2012) and Sherryl Vint’s Animal Alterity (2012), as well as her paper “Animals and Animality from the Island of Moreau to the Uplift Universe,” in the Yearbook of English Studies (2007).

I’m talking about reading science fiction not as prediction but rather as contemporary insight, dated exactly at the moment of its writing. Its trappings and excess aren’t escapism, or not entirely, but rather act as genuine confrontation. I think the whole array of science fiction, fantasy, and horror can express and develop sensitive real-life topics in ways that naturalistic stories and essays cannot.

I’d even suggest staying away from the most well-known or most-lauded authors, whose work tends to be more confirmatory, such as Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, and Isaac Asimov, although isolated works can qualify, as with the latter’s I Robot stories. It’s the dissenting, weird ones I recommend: Fredric Brown, Jack Vance, Alfred Bester, and especially Fritz Leiber; and from the freewheeling 1960s and 1970s, wilder work from Harlan Ellison and his editorial work Dangerous Visions, Norman Spinrad, Philip K. Dick, James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon), Stanislaw Lem, Arkadi and Boris Strugatski, and Gene Wolfe, just to name a few. The engineering-style, technical branding of science fiction during the 1940s and 1950s seems now to me like a minor editorial artifact, as the more psychedelic and less concerned with technical accuracy it became, the harder the “reality slap” it delivered.

Although “reality-slap” science fiction is not as prevalent in cinema and TV, the minority thereof is strikingly powerful. The original Star Trek series is almost entirely submerged beneath the weight of the franchise and fandom, but some day perhaps it could be revisited as itself, especially in partnership with the British show—almost an extension of it—Blake’s 7. The first four Planet of the Apes films may represent the high-water mark of questioning human exceptionalism in any endeavor whatsoever for the twentieth century. In series media, sometimes the tension with “don’t meddle” content is a productive thing of its own, and these all provide a lot of content for that analysis—maybe more than any number of more formal, more academically recognized discussions.

Well, that’s it for the “Big Thinks”: “read some science fiction.” It seems a feeble thing, but where formal philosophy and science have fallen short, maybe The Island of Doctor Moreau still shows the way.

1.Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Basis of Morality, 1818, included in Philosophical Writings, edited by Wolfgang Schirmacher, published by The Continuum Publishing Company, 1994.