WHEN WHITEMAN REQUESTED a new work from him in the fall of 1923, Gershwin at first declined, because of his commitment to Sweet Little Devil. Then, early in January, reading a newspaper article about Whiteman’s upcoming Aeolian Hall venture, he was surprised to learn that he was—apparently—at work on a symphony for that very concert. “This was news,” he remembered thinking; but the false report pushed him to reconsider:

There had been so much chatter about the limitations of jazz, not to speak of the manifest misunderstandings of its function. Jazz, they said, had to be in strict time. It had to cling to dance rhythms. I resolved, if possible, to kill that misconception with one sturdy blow. Inspired by this aim, I set to work composing with unwonted rapidity. No set plan was in my mind—no structure to which my music would conform. The rhapsody, as you see, began as a purpose, not a plan.1

Beginning in 1920, as we have seen, Gershwin had composed a number of songs drawing upon blues music for material.2 But for his first major instrumental work, he now set his sights on a jazz-oriented approach, more varied than a succession of blues-based statements. The concert would give Gershwin a chance to visit broader rhythmic territory, including a variety of tempos. Freedom in that realm, he felt, would call for music more unpredictable and expressive than anything Whiteman and Company—or his competitors—had so far embraced.

Gershwin’s first title for his new composition was American Rhapsody. It was Ira who came up with a new title reflecting his brother’s foray into an unexplored musical zone: a register of sorts, like a key, for a classical composition with dance rhythms, songful theatrical tunes, and a pitch vocabulary grounded in blues music. “Rhapsody in Blue” signified an intent to display in one composition the full spirit of Paul Whiteman’s “Experiment in Modern Music.”

Later in life Gershwin recalled an extraordinary train trip early in 1924 from New York to Boston, where Sweet Little Devil was soon to play, after he had begun work on the Rhapsody. Certain sounds along the way struck him, including “the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty-bang that is often so stimulating to a composer.” On this trip, too, something happened that had never happened to him before: “I suddenly heard—and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end.” By the time the train reached Boston, he could envision “a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance . . . a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness.” By that time most of the new work’s themes were already in his head, except for one—his “middle theme,” perhaps the piece’s most memorable, which had already come to him unbidden as he played the piano at a New York friend’s house. “There I was rattling away without a thought of rhapsodies in blue or any other color,” he recalled. “All at once I heard myself playing a theme that must have been haunting me inside, seeking outlet. No sooner had it oozed out of my fingers than I knew I had found it.”3

It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of several decisions that Gershwin acted on after he joined Whiteman’s “Experiment.” Foremost among them was to compose his first full-fledged instrumental work with a clear purpose in mind: to refute the notion that jazz music was bound to a strict tempo. Presenting five different themes in contrasting keys, timbres, moods, and tempos, the new composition offered listeners a sequence of independently compelling musical events, each of them eminently tuneful, and none of them given a chance to wear out its welcome.

Gershwin also opted to deploy these themes in a concerto-based format, with musical material distributed through dialogue between the ensemble and himself: an accomplished pianist whose personal panache he could trust. This medium fit well into the format of Whiteman’s concert, organized in two halves. The first was devoted to short, song-based, jazz-oriented arrangements for the ensemble, and the second to compositions with more ambitious artistic intent, beginning with Victor Herbert’s four-movement Suite of Serenades. Aware that Gershwin had composed a compelling exemplar of American musical modernism, Whiteman gave the Rhapsody in Blue the penultimate place in the concert’s order.4 That strategic placement reflected the music’s qualities rather than Gershwin’s reputation, for he was then hardly known in the precincts of Aeolian Hall, known as a venue for classical music-making.5 And the Rhapsody’s concerto format created an eventful interchange, with a soloist who knew how to project a star’s authority to complement the polished professionalism of Whiteman, the conductor, and his musicians.

Gershwin further enhanced this concerto-style invention and technique by casting his jazz-oriented melodies in the mold of popular songs. Rhythmic elasticity from the classical sphere broadens the work’s range of expression beyond the conventions of dance-based jazz music, even as Gershwin’s command of vernacular melodic invention enabled him to harvest from the plenitude of his songwriting labors. The Rhapsody’s audience hears a flowing blend of music suited at times to the concert hall, but infused elsewhere with elements from the dance hall and the theater. That discontinuity is balanced by captivating tunefulness.

A masterstroke of another kind was Gershwin’s decision to launch the piece with an unexpected sound—not a melody but a surprise: a reedy smear borrowed from the comic realm of jazz novelty. Starting on a low F deep in the clarinet’s range, Ross Gorman, Whiteman’s premier reed man, played an extended, throaty trill, followed by a seventeen-note sweep up two octaves and a fourth to the first note of the first theme: a concert B-flat. Henry O. Osgood, a New York music journalist who attended at least one rehearsal and the premiere, credits Gorman with figuring out how to make the sound of this takeoff gesture unforgettable:

Will any one who heard him forget the astonishment he created in that first measure, when, halfway up the seventeen-note run, he suddenly stopped playing separate notes and slid for home on a long portamento that nobody knew could be done on a clarinet? It’s a physical impossibility; it’s not in any of the books; but Ross knew it could be done with a special kind of reed and he spent days and days hunting around till he found one.6

The “musical kaleidoscope of America” that had revealed itself to Gershwin on his trip to Boston follows the clarinet eruption, which morphs into the first theme he has chosen for his Rhapsody. (It seems clear that he found most of his themes in his tune book, that is, “the trunk.”) That thematic unveiling leads into a musical conversation among the composition’s three “voices”: the piano soloist, the full orchestra, and solo instruments from the latter. As a mix of thematic statements with figuration, transitions, and plenty of free-flowing “tempo rubato,” the Rhapsody’s opening measures offer a prologue with an unusual richness of thematic substance. But when does this introductory process come to an end? In fact, not until Gershwin unveils a sustained stretch of complete melodies, in measures 72–130, may listeners feel sure that the piece is fully under way.

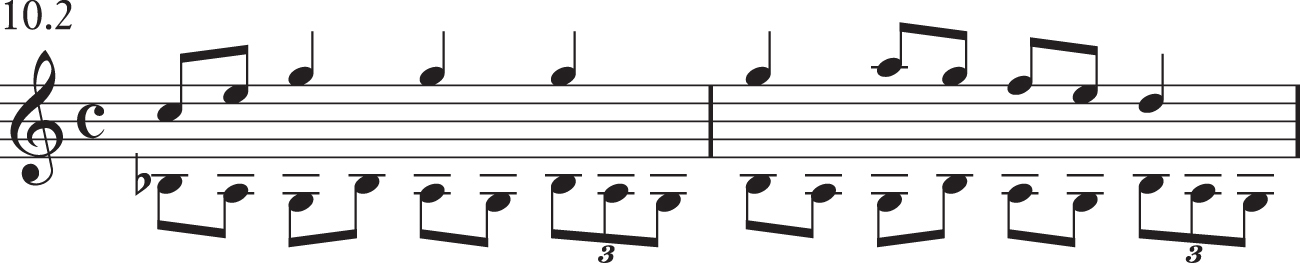

By that time Gershwin has presented three of the Rhapsody’s five themes, each cast to fit the mold of a sixteen-bar popular song refrain: aaba. And the purposeful momentum following the on-and-off flow of the opening is sustained through a fourth theme, beginning in measure 138, with a mid-to-low register that provides a contrast with its predecessors. Examples 10.1–10.5 show, in notated form, the beginnings of these themes, and that of the middle theme too.

Gershwin has also introduced a sixth melodic element: a snippet labeled “Tag” here, and heard throughout the Rhapsody to complete more than one musical statement.7

Having presented four themes as orchestral statements, Gershwin then begins, in measure 172, an extended interlude for the piano. Beginning with a transition, it offers a playful keyboard restatement of Theme 3. Then, behind a dreamy, transparent orchestral return of Theme 1, the pianist moves on to a delicate, dissonant, treble-dominated background of figuration. That interlude continues with vigorous statements from Theme 4, leading into a hushed four-bar preparation, “rubato e legato” (free and smooth), for the dramatic arrival of the Rhapsody’s mood-changing middle theme—Theme 5. Marked “Andantino,” this lyrical melody for the orchestra introduces a sweeping legato statement fashioned from three arching phrases, each unfolding over a span of twenty-two bars.

Ferde Grofé, a composer himself and the arranger of Gershwin’s two-piano score of the Rhapsody for Whiteman’s ensemble, preserved his recollections of that process, testifying to his own love for that theme. Grofé’s memory also offers a rare glimpse of the Gershwin family at home: Morris, Rose, Ira, George, Arthur, and Frances. At the time they were living in a modest first-floor apartment, with a baby grand piano in the parlor, at the corner of 110th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, across the street from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.8

Aware of the composer’s plan to change the pace and mood of the Rhapsody well along in the piece, Grofé sensed that Gershwin’s first attempt to write an effective “middle” theme had fallen short. But when Gershwin played him another melody in a lyrical vein—the “entrancing middle theme” that had recently come to him at the piano—the arranger found it perfect. He wrote it down, took it home, and returned the next day with that melody in lead-sheet form. Ira advised George that he would be hard pressed to write “another tune as good as this.” The dignity and substance of the new theme prompted Gershwin to sound it three consecutive times: twice in the orchestra, the second in “grandioso” fashion, and the third as a memorable piano solo.

But when the pianist shifts abruptly from the long sweep of lyrical melody to a noise of alarm, and a trombone sounds the middle theme in raucous eighth notes, the beginning of the end is nigh. Led by the piano, Gershwin’s coda includes a keyboard rendering of the introductory clarinet smear, several iterations of the long-absent tag, and eventually a sudden key change from E-flat to B-flat, wrenching the Rhapsody back to its home key. A thundering return of Theme 1 rings out. And as the orchestra sustains the tonic harmony’s return, the piano’s triumphant sounding of the tag bids farewell.

CRITICAL RESPONSES to Whiteman’s “Experiment in Modern Music” provide a range of perspectives on New York’s music scene as the decade of the 1920s approached its midpoint. At one end of this purview, though Aeolian Hall was hardly on their regular beat, were two show-business trade weeklies, Variety and the New York Clipper. At the other, respected music critics from the daily newspapers formed their own cultural spectrum, taking the concert’s aspirations seriously. More than one followed his concert review with a longer piece ruminating further on Whiteman’s venture.

The Variety review, written by Abel Green—one of the journal’s leading reporters, later to become its editor in chief—treated the concert as a subspecies of stage revue, citing a number’s catchiness or a lack therof, performance virtuosity, and comments on the audience response. Faced with Gershwin’s radically original composition, Green mustered two approving sentences: “Another highlight on the program was George Gershwin’s intricate and musicianly ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ played by the brilliant young composer to orchestra accompaniment. The arrangement is a gem and forced Gershwin to retire and come back for extra bends three times before permitted to finally depart.”9 A day later, Green wrote another review that offered much more detail.10 Parting company with “highbrow critics,” he remarked on the varied pedigrees of Whiteman’s customers: Tin Pan Alley publishers and song pluggers rubbing shoulders with denizens of the cultural elite, Amelita Galli-Curci, Mary Garden, Alma Gluck, Fannie Hurst, Heywood Broun, Walter Damrosch, Jules Glaenzer, Leopold Godowsky, Sr., Jascha Heifetz, Victor Herbert, Otto H. Kahn, S. Jay Kaufman, Fritz Kreisler, John McCormack, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Max Reinhardt, Moriz Rosenthal, Gilbert Seldes, Leopold Stokowsky, Deems Taylor, and Carl Van Vechten among them.The Rhapsody, the program’s highlight, “was a lengthy number but its intricate arrangement of the clever rhythm made a deep impression. It brings to the fore the native Negro indigo strains mixed with rhapsodical arrangements in a delightfully ingratiating manner.” Green was one of few in the critical fraternity who cited “Negro strains” in the composer’s mix of styles.

Lawrence Gilman of the Tribune compared the Rhapsody in Blue with two other song arrangements performed at the concert, “Raggedy Ann” by Jerome Kern and “I Love You” by Harry Archer, however, and found no significant difference between them. The new work sounded to him like just another example of Whiteman’s own kind of American dualism: a “paradoxical blend of independence and docility, care-free energy and unadventuresome conformity.”11

But to Olin Downes, who had recently moved from Boston to New York to take over the Times’s music beat, Whiteman’s concert brimmed with musical vitality. Downes heard in the players’ performance “an abandon equaled only by that race of born musicians—the American Negro, who has surely contributed fundamentally to this art which can neither be frowned nor sneered away.” The Rhapsody’s

first theme alone, with its caprice, humor, and exotic outline, would show a talent to be reckoned with. . . . This is no mere dance tune set for piano and other instruments. It is an idea, or several ideas correlated and combined, in varying and well-contrasted rhythms that immediately intrigue the hearer. This, in essence, is fresh and new and full of future promise.

Downes saw the classically inexperienced Gershwin as locked in a struggle with form, but his verdict was positive: “The audience was stirred, and many a hardened concertgoer excited with the sensation of a new talent finding its voice and likely to say something personally and racially important to the world.”12

W. J. Henderson of the New York Herald, who admired the Rhapsody greatly, started his review with a bang: “Modern music invaded Aeolian Hall yesterday afternoon.” Igor Stravinsky, he imagined, “would have shaken hands with Irving Berlin, Gershwin and Paul Whiteman and shouted (in Russian, of course), ‘Great is rhythm! Great is dance! Great are wind instruments! And we are the silver trimmed prestidigitators who know how to use them all!’ ”13 And in a later revisiting of what he had heard, Henderson added:

There could be no question about the musical quality of Mr. Gershwin’s work. It was as genuine in its field as one of Liszt’s Hungarian rhapsodies, and in some respects quite as good. It was too long because it was over elaborated in some rather tenuous spots, and for that reason it was loose jointed in other places. But it was the work of a musician and one of unquestionable talents.14

Deems Taylor reviewed Whiteman’s concert for the New York World’s Wednesday edition, and then, as he had after Eva Gauthier’s song recital, followed it on Sunday with a longer piece about issues the concert had raised. As a composer himself, Taylor cared about where this event fit in Whiteman’s view of the contemporary scene, not only “jazz as it is to-day, but jazz as it was and may become.” To his ear, the Rhapsody “possessed at least two themes of genuine musical worth and displayed a latent ability on the part of this young composer to say something of considerable interest in his chosen idiom.”

Whatever its faults, the piece hinted at something new. “Mr. Gershwin will bear watching,” Taylor wrote; “he may yet bring jazz out of the kitchen.”15