1 The Limitless Forms of Kṛṣṇa

Fashioning Divine Bodies

In the Introduction I briefly surveyed some of the new forms of divine embodiment that emerged in the Indian religiocultural landscape with the rise of bhakti traditions in the period between 200 BCE and the early centuries of the Common Era. In this chapter I will focus on the ways in which these general trends find robust and particularized expression in the discourse of divine embodiment developed by early Gauḍīya authorities in the sixteenth century CE. The Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment celebrates the deity Kṛṣṇa as ananta-rūpa, “he who has endless forms,” his limitless forms encompassing and interweaving the various planes of existence. This discourse is delineated by Rūpa Gosvāmin in his Laghubhāgavatāmṛta and is systematically elaborated by Jīva Gosvāmin in his Bhagavat Sandarbha, Paramātma Sandarbha, and Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha. Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja encapsulates the key elements of the Gosvāmins’ formulations in his Caitanya Caritāmṛta. As mentioned in the Introduction, in addition to providing an elaborate theory of Kṛṣṇa’s divine forms on the transcosmic, macrocosmic, and microcosmic planes, the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment includes a number of “mesocosmic,” or intermediary, forms that serve as concrete means through which bhaktas can encounter and engage the concentrated presence of the supreme Godhead in localized forms in the gross material realm.

The Absolute Body and Its Endless Manifestations: The Gauḍīya Discourse of Divine Embodiment

In his recent study of Jīva Gosvāmin’s contributions to Indian philosophy, Ravi Gupta argues that Jīva, as one of the principal architects of the Gauḍīya theological edifice, helped to construct a distinct system of theology—Caitanya Vaiṣṇava Vedānta, or Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Vedānta—by bringing into dialogue “four powerful streams of classical Hinduism: (1) the various systems of Vedānta; (2) the ecstatic bhakti movements; (3) the Purāṇic commentarial tradition; and (4) the aesthetic theory of Sanskrit poetics.”1 I would contend that this integrative tendency is particularly evident in the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, as articulated not only by Jīva Gosvāmin but also by Rūpa Gosvāmin and Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja. Moreover, I would argue that this integrative tendency is itself at times used in the service of a broader principle, which I term the principle of “superordination.” Through this principle the Gauḍīya authorities attenuate the challenges posed by competing traditions by selectively appropriating and accommodating elements of those traditions’ teachings and integrating them into an encompassing hierarchical system that ultimately serves to domesticate and subordinate the competition. In the following analysis we shall see how this principle of superordination is at work in the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, which constructs a number of hierarchical taxonomies that classify and rank the multifarious divine forms of Kṛṣṇa as ananta-rūpa. In delineating these taxonomies the Gauḍīyas appropriate and subordinate elements of the teachings propounded by competing philosophical schools and bhakti traditions and establish a multidimensional hierarchy of ontologies, paths, and goals in which their own distinctive form of embodied Kṛṣṇa bhakti is represented as the pinnacle of spiritual realization.

Bhagavān’s Absolute Body and Self-Referral Play

The most important of the Gauḍīya taxonomies involves a hierarchical assessment of the three aspects of the supreme Godhead, from lowest to highest: Brahman, Paramātman, and Bhagavān. As we shall see, in allotting the highest place in their ontological hierarchy to Bhagavān, who is represented as a personal Godhead endowed with an absolute body, infinite qualities, and innumerable śaktis (energies), the early Gauḍīya authorities engage in a polemic that challenges the contending ontologies of two rival philosophical schools: the monistic ontology of Advaita Vedānta, which identifies the ultimate reality with the impersonal, formless Brahman, and the dualistic ontology of Pātañjala Yoga, which posits a plurality of nonchanging, formless puruṣas as the highest reality.

Brahman, Paramātman, and Bhagavān

To provide a scriptural basis for their hierarchical assessment of the three aspects of the Godhead, the Gauḍīyas invoke Bhāgavata Purāṇa 1.2.11 and interpret the order of terms in the verse as indicating increasing ontological importance: “The knowers of reality declare the ultimate reality to be that which is nondual knowledge. It is called Brahman, Paramātman, and Bhagavān.”2 In Gauḍīya formulations these three aspects of the Godhead are associated with different dimensions of embodiment. Brahman, the lowest aspect of the Godhead, is the impersonal, formless, attributeless, and undifferentiated ground of existence that is beyond the material realm of prakṛti and is the radiant effulgence of the absolute body of Bhagavān. Paramātman, the intermediary aspect of the Godhead, is the indwelling Self, who on the macrocosmic level animates the innumerable universes, or cosmos bodies, and on the microcosmic level resides in the hearts of all jīvas, embodied beings. Bhagavān, the highest aspect of the Godhead, is transcosmic—beyond both the macrocosmos and the microcosmos—and is personal, endowed with an absolute body (vigraha), replete with infinite qualities (guṇas), and possessed of innumerable śaktis. Bhagavān is ascribed the status of the Godhead in his complete fullness (pūrṇa), who encompasses within himself Brahman and Paramātman and is at the same time beyond both.

In the first seven sections (anucchedas) of the Bhagavat Sandarbha, Jīva Gosvāmin introduces the three aspects of the Godhead, Brahman, Paramātman, and Bhagavān. He then provides an extended analysis of the nature of Bhagavān in the remaining sections of the Bhagavat Sandarbha and an extended analysis of the nature of Paramātman in the Paramātma Sandarbha. In a not-so-veiled critique of Advaitin claims regarding the ultimacy of Brahman, Jīva insists that it is not necessary to devote a separate Sandarbha to an analysis of Brahman because the Bhagavat Sandarbha, by providing a full explication of the nature of Bhagavān, simultaneously serves to clarify the nature of Brahman as an incomplete manifestation (asamyag-āvirbhāva) of Bhagavān.3 After expounding the three aspects of the Godhead in the Bhagavat Sandarbha and Paramātma Sandarbha, Jīva’s principal concern in the Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha is to establish Kṛṣṇa’s supreme status as pūrṇa Bhagavān, the full and complete Godhead. In this context he invokes the declaration in Bhāgavata Purāṇa 1.3.28 that “Kṛṣṇa is Bhagavān himself (Bhagavān svayam)” as the mahā-vākya, authoritative scriptural utterance, that is the definitive statement of the entire Purāṇa. Moreover, he goes even further and argues that because the Bhāgavata Purāṇa is the “sovereign of all śāstras (scriptures),”4 the canonical authority of the Bhāgavata’s mahā-vākya is indisputable and establishes the supreme truth at the basis of all śāstras, to which all apparently contradictory scriptural statements must be reconciled.5

Bhagavān’s Self-Referral Play with His Śaktis

The Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment emphasizes that Bhagavān is śaktimat, the possessor of innumerable śaktis, energies or powers. The three principal types of śakti are the svarūpa-śakti, māyā-śakti, and jīva-śakti. The svarūpa-śakti operates on the transcosmic level as the śakti that is intrinsic (antar-aṅga) to Bhagavān’s essential nature (svarūpa), comprising three aspects: saṃdhinī-śakti, the power of sat, being; saṃvit-śakti, the power of cit, consciousness; and hlādinī-śakti, the power of ānanda, bliss. The māyā-śakti operates on the macrocosmic level as the śakti that is extrinsic (bahir-aṅga) to Bhagavān and that is responsible for manifesting and regulating the material realm of prakṛti and for subjecting jīvas, individual living beings, to the bondage of saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. The jīva-śakti operates on the microcosmic level as the intermediary (taṭasthā, literally, “standing on the border”) śakti that constitutes jīvas as, on the one hand, an aṃśa, or part, of Bhagavān in the svarūpa-śakti and, on the other hand, subject to the binding influence of the māyā-śakti.

Jīva introduces the three principal types of śakti in the Bhagavat Sandarbha and then focuses on the svarūpa-śakti that is intrinsic to Bhagavān’s essential nature. In the Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha, after establishing that Kṛṣṇa is svayaṃ Bhagavān, he further explicates the svarūpa-śakti through an extended analysis of Kṛṣṇa’s essential nature (svarūpa), absolute body (vigraha), transcendent abode (dhāman), and eternal associates (parikaras or pārṣadas). He provides an analysis of the functions of the māyā-śakti and the jīva-śakti in relation to Paramātman in the Paramātma Sandarbha.

In his discussions of the three types of śakti, Jīva provides the earliest formulation of the distinctive ontology of the Gauḍīya Sampradāya in which the relationship between Bhagavān, as the śaktimat, and his śaktis is represented as acintya-bhedābheda, inconceivable difference-in-nondifference. The śaktis exist in an inconceivable (acintya) relationship to the śaktimat in which they are held to be aṃśas, parts, of Bhagavān that are simultaneously nondifferent (abheda) from him, partaking of his divine nature, and distinct (bheda) from him, as parts of his encompassing wholeness. S. K. De emphasizes the significance of this ontological formulation, which serves to distinguish the Gauḍīya Sampradāya from other Vaiṣṇava schools:

[T]he relation between the Śaktis and the Possessor of the Śaktis is represented as an incomprehensible (acintya) relation of sameness and difference (bhedābheda), the whole theory thus receiving the designation of Acintya-bhedābheda-vāda (incomprehensible dualistic monism), a peculiar point of view which distinguishes the Bengal school from other Vaiṣṇava schools by the qualifying word acintya which brings in a mystical attitude. It speaks of the inconceivable existence of distinction and non-distinction. The Śaktis are non-different from the Bhagavat, inasmuch as they are parts or Aṃśas of the divine being; but the very fact that they are parts only makes the superlativeness of divine attributes inapplicable to them, and there is thus an inevitable difference.6

The section of Jīva’s analysis that is critical to our understanding of the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment concerns the structures and dynamics of the svarūpa-śakti. The svarūpa-śakti, as explicated by Jīva, assumes two forms: the svarūpa, which is Bhagavān himself in his essential nature and absolute body; and the svarūpa-vaibhava, which includes his transcendent abode, dhāman, and his eternal associates, parikaras or pārṣadas. The svarūpa-śakti also includes Kṛṣṇa’s līlā, divine play, as svayaṃ Bhagavān, which is represented as the spontaneous expression of the hlādinī-śakti, the bliss that is intrinsic to Bhagavān’s essential nature. The transcendent dhāman is called Kṛṣṇaloka and is the domain where Kṛṣṇa engages eternally in his līlā. Kṛṣṇaloka is subdivided into three dhāmans. The innermost dhāman is the transcendent Vraja-dhāman, which is also called Goloka, Gokula, Vṛndāvana, or Goloka-Vṛndāvana and is the transcosmic prototype of the earthly region in North India that is variously designated as Vraja, Gokula, or Vṛndāvana. The two outer dhāmans of Kṛṣṇaloka are called Mathurā and Dvārakā and are the transcosmic prototypes of the earthly cities of Mathurā and Dvārakā. Building on Rūpa Gosvāmin’s formulations in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta, Jīva seeks to establish that Kṛṣṇa’s līlā, which is recorded in narrative form in the tenth book of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, occurs on both the manifest (prakaṭa) and unmanifest (aprakaṭa) levels. The Bhāgavata Purāṇa portrays Kṛṣṇa as descending to the material realm and unfolding his līlā on earth at a particular time and place in history: in the terrestrial region of Vraja in North India at the end of Dvāpara Yuga in the current manvantara (interval of Manu) known as Vaivasvata Manvantara in approximately 3000 BCE.7 In a hermeneutical turn that is critical to the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, Jīva interprets this earthly līlā as the manifest counterpart of the unmanifest līlā that goes on eternally within Bhagavān in Kṛṣṇaloka beyond the material realm of prakṛti and beyond Brahman. He also ascribes an eternal status to the cowherds (gopas), cowmaidens (gopīs), and other companions of Kṛṣṇa who are the key characters in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa’s literary account of the divine drama in Vraja. Kṛṣṇa’s foster parents Nanda and Yaśodā, attendants, cowherd friends, and cowmaiden lovers are represented as his eternal associates, parikaras or pārṣadas, eternally perfect beings who participate in his essential nature as part of the svarūpa-śakti and engage with him eternally in the unmanifest līlā in his transcendent Vraja-dhāman.1

Jīva is concerned to illumine more specifically the relationship between Kṛṣṇa and the gopīs, the cowmaidens of Vraja, portrayed in the rāsa-pāñcādhyāyī, chapters 29 to 33 of the tenth book of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, which celebrate in lavish detail Kṛṣṇa’s love-play with the gopīs, culminating in the rāsa-līlā, the circle dance of Kṛṣṇa with his cowmaiden lovers.9 Jīva argues that the gopīs are the eternal expressions of the hlādinī-śakti, the blissful aspect of the svarūpa-śakti. Among the gopīs, he identifies Rādhā with the anonymous gopī who is singled out for Kṛṣṇa’s special attention in Bhāgavata Purāṇa 10.30.24–44, and he invests her with the highest ontological status as Kṛṣṇa’s eternal consort who is the quintessential expression of the hlādinī-śakti and consummate embodiment of Kṛṣṇa’s bliss, from whom the other gopīs emanate as manifestations of that bliss. The unmanifest līlā of Kṛṣṇa with Rādhā and the gopīs is thus interpreted in terms of the inner dynamics of the Godhead as self-referral play within Bhagavān in which he revels eternally with the blissful impulses of his own nature.

When Kṛṣṇa descends to earth at the end of Dvāpara Yuga, Rādhā and the gopīs and the other eternal associates are represented as descending with him to the terrestrial region of Vraja in North India, where he displays his manifest līlā. The līlā is thus understood as a process of self-disclosure through which Kṛṣṇa revels on the unmanifest plane in the rapturous delights of his own divine play and expresses himself on the manifest plane in a series of episodes that display different aspects of the divine nature.

While the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment centers on the svarūpa-śakti, the discourse of human embodiment centers on the jīva-śakti and the mechanisms of liberation from the binding influence of the māyā-śakti. The ultimate goal of human existence, as I will explore more fully in Chapter 2, is represented as the attainment of a state of realization in which the jīva is liberated from the bondage of the māyā-śakti and awakens to the reality of Kṛṣṇa as svayaṃ Bhagavān and to its true identity as an aṃśa of Bhagavān in the svarūpa-śakti. The jīva attains direct experiential realization of its eternal relationship with Bhagavān in acintya-bhedābheda, inconceivable difference-in-nondifference. Having cast off the last vestiges of bondage to material existence, the realized jīva reclaims its distinctive role in the transcendent Vraja-dhāman as a participant in the unmanifest līlā and enjoys the bliss of preman, all-consuming love for Kṛṣṇa, in the eternal embrace of the supreme Godhead.

The Absolute Body of Bhagavān beyond the Formless Brahman

One of the most striking claims of the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment is its insistence that—contrary to the ontologies of competing philosophical schools that claim that the ultimate reality in its essential nature is formless—the highest aspect of the Godhead, Bhagavān, is not without form (nirākāra) but rather is endowed with an absolute body with distinctive bodily features that is at the same time nonmaterial (aprākṛta), unmanifest (avyakta), eternal (nitya), and self-luminous (svaprakāśa). This absolute body is designated by the term vigraha. The early Gauḍīya authorities emphasize that Bhagavān’s vigraha, like his svarūpa, essential nature, consists of being (sat), consciousness (cit), and bliss (ānanda). Thus in Bhagavān there is no distinction between body and essence, vigraha and svarūpa, for the body (deha) and the possessor of the body (dehin) are nondifferent.10 Indeed, in the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, the term svarūpa is used at times to refer to Bhagavān’s essential nature and at other times to refer to his essential form, which in the final analysis are considered identical.

The Gauḍīyas assert the paradoxical notion that Bhagavān’s absolute body, in its svayaṃ-rūpa or svarūpa, essential form, is the two-armed form of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa, who is extolled in the tenth book of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as descending to earth and carrying out his līlā in the form of a gopa, cowherd boy, in the area of Vraja in North India. It is the beautiful youthful form (kiśora-mūrti) of the cowherd Kṛṣṇa—with its distinctive blue-black color, body marks, dress, ornaments, and characteristic emblems such as the flute—that is celebrated by the Gauḍīyas as the absolute body, vigraha, that exists eternally in the transcendent Vraja-dhāman, Goloka-Vṛndāvana. Rūpa Gosvāmin gives the following description of Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa:

The sweet form (mūrti) of the enemy of Madhu [Kṛṣṇa] brings me intense joy. His neck has three lines like a conch, his clever eyes are charming like lotuses, his blue-black limbs are more resplendent than the tamāla tree,…his chest displays the Śrīvatsa mark, and his hands are marked with the discus, conch, and other emblems.… This lover has a beautiful body (aṅga) and is endowed with all auspicious marks, radiant, luminous, powerful, eternally young.11

In the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta Rūpa invokes the canonical authority of the śāstras to establish that the two-armed youthful form of the cowherd Kṛṣṇa, which is unsurpassed in its beauty (lāvaṇya) and its sweetness (mādhurya), is the svayaṃ-rūpa, essential form, of the sat-cit-ānanda-vigraha, Bhagavān’s absolute body consisting of being, consciousness, and bliss. He maintains, moreover, that although the svayaṃ-rūpa is eternal (nitya), nonmaterial (aprākṛta), unmanifest (avyakta), and invisible (adṛśya), through his self-manifesting śakti (prakāśatva-śakti) Kṛṣṇa reveals his gopa form so that it can be directly “seen” (root dṛś) even today by realized bhaktas, just as it was previously “seen” (root dṛś) by Vyāsa, the acclaimed ṛṣi (seer) who recorded his cognitions of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa in the form of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa.12

Jīva Gosvāmin provides an extended analysis of Bhagavān’s vigraha in the Bhagavat Sandarbha.13 He then provides a series of arguments in the Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha, building on Rūpa’s arguments in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta, to establish that the essential form, svayaṃ-rūpa or svarūpa, of the vigraha in the transcendent Vraja-dhāman is the two-armed youthful form of a cowherd boy, which Kṛṣṇa manifests on the material plane when he descends to earth in Dvāpara Yuga and withdraws from manifestation when he returns to his transcendent dhāman after his sojourn on earth is completed. In order to establish the primacy of the gopa form, he considers three potential candidates for the svayaṃ-rūpa: (1) Kṛṣṇa’s appearance in the shape of a human being (narākāra or narākṛti) with two arms (dvi-bhuja), which is the principal form that he manifests as Gopāla Kṛṣṇa, the cowherd of Vraja; (2) Kṛṣṇa’s manifestation in the shape of a human being (narākāra or narākṛti) with four arms (catur-bhuja), which is the form that he displays at times in Mathurā and Dvārakā in his role as Vāsudeva, the Yādava prince who is the son of Vasudeva and Devakī; and (3) Kṛṣṇa’s manifestation before the warrior Arjuna in the cosmic form of viśva-rūpa with a thousand arms (sahasra-bhuja), as recounted in chapter 11 of the Bhagavad-Gītā. Jīva establishes an ontological hierarchy among these forms of Kṛṣṇa based on a series of successive dichotomies. First, he distinguishes between narākāra, Kṛṣṇa’s manifestations in the shape of a human being, and the viśva-rūpa and argues that the svayaṃ-rūpa is narākāra, not the thousand-armed viśva-rūpa, which is a secondary manifestation of this essential form. Second, among the narākāra manifestations, Jīva distinguishes between Kṛṣṇa’s two-armed, or dvi-bhuja, form, and his four-armed, or catur-bhuja, form and maintains that the svayaṃ-rūpa is Kṛṣṇa’s dvi-bhuja form, which occasionally manifests a secondary form that is catur-bhuja. Finally, among Kṛṣṇa’s dvi-bhuja manifestations, Jīva argues that the svayaṃ-rūpa in its most full and complete (pūrṇa) expression is the cowherd form of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa in Vraja, which is characterized by mādhurya, divine sweetness, and he maintains that the princely form of Vāsudeva through which Kṛṣṇa expresses his aiśvarya, divine majesty, in Mathurā and Dvārakā is a secondary manifestation of this essential form.14

This ontological hierarchy is thus used to establish that the two-armed form of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa that is the object of worship of the Gauḍīyas is the supreme (para) form of the Godhead. This hierarchy serves as a critical component of the theology of superordination by relegating to its lower rungs not only the formless Brahman of Advaita Vedānta and the formless puruṣas of Pātañjala Yoga but also the four-armed forms of Viṣṇu, such as Vāsudeva and Nārāyaṇa, that are worshiped by rival Vaiṣṇava movements. Invoking the canonical authority of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, Jīva points out that although Brahmā the creator had seen Kṛṣṇa’s four-armed aiśvarya form as Vāsudeva many times, it is Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa as the two-armed narākāra form of a youthful gopa that Brahmā chooses to glorify in all its particularity:

Even though he [Brahmā] had seen (root dṛś) the catur-bhuja form many times, for the purpose of praise he focuses specifically on the [dvi-bhuja] narākāra: “Brahmā declared: I offer praise to you, O praiseworthy one, the son of a cowherd, whose body (vapus) is dark like a rain-cloud, whose garments are dazzling like lightning, whose face is resplendent with guñjā berry earrings and a crest of peacock feathers, who wears a garland of forest flowers and has soft feet, and whose beauty is adorned with a flute, horn, staff, morsel of food, and other emblems.”15

Having established the supreme (para) status of the two-armed gopa form as Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa, essential form, Jīva advances another critical component of his argument: although the form in which Kṛṣṇa appears during his sojourn on earth has a human shape, narākāra, it is not an ordinary material human body (prākṛta-mānuṣa) composed of flesh (māṃsa) and material elements (bhūta-maya)16 but is rather an eternal (nitya or sanātana), nonmaterial (aprākṛta) absolute body consisting of sat-cit-ānanda, being, consciousness, and bliss.17 Among the arguments that he uses to establish the eternality (nityatva, avasthāyitva, or avyabhicāritva) of the narākāra,18 Jīva argues that Kṛṣṇa, who is unborn (aja) in his essential nature as svayaṃ Bhagavān,19 was not born on earth as the son of Vasudeva and Devakī through the material process of procreation like an ordinary child, but rather his vigraha first entered into the mind of Vasudeva and thereafter was deposited by Vasudeva in the mind of Devakī.

His [Kṛṣṇa’s] appearance (prādur-bhāva) in Vasudeva…did not involve entering his semen as in the ordinary material process (prākṛtavat) [of procreation]. Rather, it involved his [Kṛṣṇa’s] vigraha consisting of sat-cit-ānanda entering (āveśa) into his [Vasudeva’s] mind (manas). This is declared [in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa]: “Thereafter, just as the eastern quarter bears the bliss-bestowing moon, Devakī conceived in her mind the imperishable Lord, the Self of all, who had been deposited there by Vasudeva.…”20

According to Jīva, when Kṛṣṇa descends from his transcendent Vraja-dhāman to earth in Dvāpara Yuga, he manifests his eternal vigraha on the material plane for the duration of his earthly sojourn, after which he withdraws the manifestation of his vigraha from the earth. Jīva insists that, unlike ordinary mortals, Kṛṣṇa does not assume a temporary material body and then cast it off at the end of his sojourn. Rather he “appears” (root bhū + prādur, root bhū + āvir, or root as + āvir) on earth, making his imperishable absolute body visible (root dṛś) on the material plane for a period of time, and then he “disappears” (root dhā + antar), concealing his vigraha.21

Jīva maintains that, although the svayaṃ-rūpa of the vigraha, the two-armed narākāra form of the gopa of Vṛndāvana, is no longer visible to those whose vision is bound by materiality (prākṛta-dṛṣṭi), Kṛṣṇa’s absolute body can be “seen” (root dṛś) by those sages who are endowed with special divine vision (divya-dṛṣṭi) that is invested with the śakti of Bhagavān. Indeed, one of the key strategies that Jīva deploys to establish the eternality of the narākāra is to invoke the canonical authority of the śāstras, which he argues preserve the record of the sages’ direct experiences (vidvad-anubhava-śabda-siddha) of Kṛṣṇa’s essential form as the gopa of Vṛndāvana. He claims that sages throughout the ages have attained by means of meditation (dhyāna) direct visionary experience (sākṣāt-kāra) of the eternal absolute body of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa in his transcendent Vraja-dhāman, Goloka-Vṛndāvana, and they have recorded their experiences in the śāstras as authoritative testimonies for future generations.22

Among the śāstras that Jīva frequently cites is the Gopālatāpanī Upaniṣad, one of the post-Vedic Vaiṣṇava Upaniṣads, which the Gauḍīyas invest with the transcendent authority of śruti as the record of that which was “heard” (root śru) and “seen” (root dṛś) by the ancient ṛṣịs (seers) through direct experiential realization of the supreme Godhead, Gopāla Kṛṣṇa. He invokes in particular the following verse from the Gopālatāpanī Upaniṣad in order to provide a scriptural basis for his claim that the essential form of the eternal vigraha consisting of sat-cit-ānanda is the two-armed form of the cowherd of Vṛndāvana:

I, along with the Maruts, constantly seek to please with a most excellent hymn of praise the one and only Govinda, whose…vigraha consists of sat-cit-ānanda and who is seated beneath a devadāru tree in Vṛndāvana.23

Jīva is concerned above all to ground his arguments in the canonical authority of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the sovereign of all śāstras, which, as I will discuss in Chapter 3, he reveres as the eternal (nitya) and uncreated (apauruṣeya) record of the cognitions of Vyāsa, the acclaimed ṛṣi of ṛṣis. He maintains that Vyāsa, while immersed in samādhi in the depths of meditation, “saw” (root dṛś) the absolute body of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa in his transcendent Vraja-dhāman beyond the material realm of prakṛti and then recorded his cognitions in the form of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the śruti pertaining to Kṛṣṇa.24 He invokes a passage from the Padma Purāṇa in which Vyāsa describes his cognition of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa’s eternal vigraha:

I was thrilled with intense rapture upon seeing (root dṛś) Gopāla, adorned with all his ornaments, rejoicing in the embrace of the [cowherd] women, playing on his flute. Then svayaṃ Bhagavān, as he roamed about Vṛndāvana, said to me: “That which is seen by you is my eternal (sanātana) divine form (divya rūpa), my vigraha consisting of sat-cit-ānanda, which is undivided (niṣkala), nonactive (niṣkriya), and tranquil (śānta). There is nothing greater than this perfect (pūrṇa) lotus-eyed form of mine. The Vedas declare this to be the cause of all causes.”25

Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja, building on the arguments of Rūpa and Jīva, includes in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta a number of extended reflections on the svayaṃ-rūpa of Kṛṣṇa as the youthful cowherd boy whose body consists of sat-cit-ānanda.

Hear…a discussion of the svarūpa of Kṛṣṇa: the truth of knowledge of the non-dual is the son of Vrajendra [Kṛṣṇa] in Vraja. He is the beginning of all things, the container of all things, the crown of youth [kiśora]; his body [deha] is cit and ānanda, the refuge of all, the Lord of all.26

As I will discuss in a later section, one of Kṛṣṇadāsa’s principal concerns is to establish that although the vigraha of Bhagavān remains one, he has the capacity to assume limitless (ananta) divine forms on the various planes of existence.27

The Gauḍīya Challenge to Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga

In the course of the six Sandarbhas, Jīva Gosvāmin provides a systematic philosophical exposition of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Vedānta in which he seeks to elucidate not only the nature of the ultimate reality (sambandha) but also the goal of human existence (prayojana) and the means to the goal (abhideya).28 In the process he constructs an encompassing hierarchical taxonomy that provides a ranked assessment of the contending ontologies, paths, and goals promulgated by rival philosophical schools. In particular, by allotting the highest place in the Gauḍīya ontological hierarchy to Bhagavān, the transcosmic personal Godhead, and relegating Brahman and Paramātman to subordinate positions as partial aspects of Bhagavān, Jīva engages in a polemic that is aimed both implicitly and explicitly at challenging the ontologies, paths, and goals advocated by the exponents of Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga. In the Caitanya Caritāmṛta Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja recasts this polemic in the form of explicit debates in which Caitanya is portrayed as disputing and refuting exponents of Advaita Vedānta, Sāṃkhya, Pātañjala Yoga, and other philosophical schools.

The philosophers and Mīmāṃsikas and followers of the Māyāvāda [Advaitins], and Sāṃkhyas and Pātañjalas, and followers of smṛti and the purāṇas and āgamas—all were vastly learned in their own śāstras. Prabhu [Caitanya] examined them critically and faulted the opinions of all of them. Everywhere Prabhu established the Vaiṣṇava doctrines, and no one was able to fault the doctrines of Prabhu. Being defeated one after the other, they accepted Prabhu’s opinions.29

Among the contending philosophical schools, the early Gauḍīya authorities are above all concerned to position themselves in relation to their archrivals, the Advaitins, and in this context they display contrasting attitudes towards the divergent forms of Advaita Vedānta that they encounter in classical Advaitin texts and in the Indian landscape. On the one hand, they reject the radically nondualist form of classical Advaita Vedānta expounded by Śaṃkara (c. 788–820 CE), which fosters a monistic ontology along with the theory of māyā (illusion) and champions jñāna—and more specifically Brahma-vidyā, knowledge of Brahman—as a distinct path, the jñāna-mārga, that is the only efficacious path to realization. On the other hand, they were directly influenced by certain bhakti-inflected forms of Advaita Vedānta that began to circulate from the fourteenth century CE on. These bhakti-oriented Advaitins include Śrīdhara Svāmin (c. fourteenth to fifteenth century CE), the author of Bhāvārthadīpikā, the acclaimed commentary on the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, who promulgates in his commentary a theistic nondualism that provides, as Daniel Sheridan has emphasized, “a good illustration of the inclusivity and accommodation of the later Advaitins with respect to theistic bhakti.”30 Śrīdhara’s bhakti-inflected Advaita appears to have influenced certain Advaitins of the Purī order, one of the ten orders of saṃnyāsins (renunciants) established by Śaṃkara, which is associated with the Śṛṅgerī Maṭha in South India. Among the most prominent of the Vaiṣṇava-oriented Advaitins of the Purī order who exerted a decisive influence on Caitanya and his followers are Viṣṇu Purī (c. fifteenth century CE), the compiler of the Bhaktiratnāvalī, an anthology of Sanskrit verses from the Bhāgavata Purāṇa that was translated into Bengali, and Mādhavendra Purī (c. 1420–1490 CE), the celebrated parama-guru, supreme guru, of Caitanya and of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava movement inspired by him.31

Caitanya was formally introduced to this Vaiṣṇava-oriented tradition of Advaitin renunciants by his two immediate gurus, who are both included among the disciples of Mādhavendra Purī: Īśvara Purī, Caitanya’s dīkṣā-guru from whom he received initiation into the Kṛṣṇa-mantra, and Keśava Bhāratī, his saṃnyāsa-guru from whom he received initiation into the Bhāratī order of Advaitin saṃnyāsins, which, like the Purī order, is associated with the Śṛṅgerī Maṭha in South India.32 Īśvara Purī is represented in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta as a favorite disciple of Mādhavendra Purī, who, as the guru of Caitanya’s guru, is revered as the parama-guru from whom the many-branched tree of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava bhakti first sprouted:

Glory to Śrī Mādhava Purī, the stream of Kṛṣṇa-prema; he was the first sprout of the wishing-tree of bhakti. The sprout was nourished, in the form of Śrī Īśvara Purī; Caitanya-mālī [the gardener] himself became the main trunk; that trunk is the basic source of all the branches.33

Although an Advaitin saṃnyāsin, Mādhavendra Purī is portrayed in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta as the embodiment of ecstatic bhakti who eschews the radical nondualism of Śaṃkara and extols the glories of Kṛṣṇa-preman over the “dry jñāna” of Brahma-vidyā.34 In addition to Mādhavendra Purī, whom Friedhelm Hardy argues was “the figure of central importance for the bhakti of Caitanya,”35 Caitanya is represented as holding in high esteem another bhakti-oriented Advaitin saṃnyāsin, Śrīdhara Svāmin. Caitanya defends the authority of Śrīdhara’s interpretations of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and declares, “We know the Bhāgavata through the grace of Śrīdhara Svāmī; Śrīdhara Svāmī is the guru of the world, and I honor him as guru.”36

Even though Caitanya is represented in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta as affiliated with certain devotionally-oriented Advaitin saṃnyāsins, both through his lineage of gurus and through his own initiation into the Bhāratī samṇyāsin order, at the same time he is portrayed as denouncing those Advaitins whom he deems “māyāvādins” and “dry jñānins” devoid of bhakti who perpetuate the radical nondualism of Śaṃkara. Caitanya’s refutation of Śaṃkara’s teachings is vividly framed in the form of a debate with a group of Advaitin saṃnyāsins in Vārāṇasī headed by Prakāśānanda Sarasvatī, a renowned scholar of Vedānta. Prakāśānanda criticizes Caitanya for abandoning his dharma as a saṃnyāsin and, instead of engaging in the study of Vedānta, wasting his time dancing and singing the name of Kṛṣṇa in the company of “emotionalists” (bhāvukas). Caitanya responds by refuting Śaṃkara’s interpretation of the Brahma-Sūtras, or Vedānta-Sūtras, in his Brahma-Sūtra Bhāṣya, which he claims neglects the primary meaning (mukhya-vṛtti), the most direct and obvious meaning, and gives precedence instead to the secondary meaning (gauṇa-vṛtti).

The Vedānta Sūtra is the word of Īśvara [the Lord], which Śrī Nārāyaṇa spoke when in the form of Vyāsa. Error, confusion, contradiction, want of skill—these faults are not present in the word of Īśvara. Together with the Upaniṣads the sūtra speaks the truth, and that meaning is of the greatest excellence and is easily perceived. But the Ācārya [Śaṃkara] made the bhāṣya [commentary] according to the secondary meaning, and by listening to him all things are destroyed.… [H]e expounded the secondary meaning, hiding the primary one. The chief meaning in the word brahma[n] is Bhagavān, made up of cit and divinity and none is equal or superior to him.37

While Caitanya is thus represented as denouncing the radically nondualist form of Advaita Vedānta advanced by Śaṃkara, Jīva Gosvāmin’s relationship to Śaṃkara’s teachings is more complex. In constructing Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Vedānta as a distinct system of theology, Jīva builds upon, while at the same diverging from, the contending systems of Vedānta expounded by Śaṅkara and the founders of the other principal Vedānta schools, Rāmānuja and Madhva. As Gupta has emphasized, Jīva is “heavily indebted to earlier teachers for his understanding of the Brahma-sūtra—specifically, Rāmānuja, Śrīdhara Svāmī, Madhva, and Śaṅkara,” and he “possesses an intimate working knowledge of his sources,” including Śaṃkara’s Brahma-Sūtra Bhāṣya.38 He is particularly indebted to Śrīdhara Svāmin, whose commentary on the Bhāgavata Purāṇa he frequently invokes, citing with approval his interpretations that “accord with pure Vaiṣṇava principles” while jettisoning any comments that promote a strictly monistic Advaitin ontology.39 Jīva also selectively invokes Śaṃkara’s commentary on the Brahma-Sūtras, deploying at times his terminology, hermeneutical strategies, and modes of argumentation to support his own interpretations of the Brahma-Sūtras and to buttress his own arguments regarding such issues as the uncreated (apauruṣeya) and eternal (nitya) status of the Vedas.40 At the same time, however, as I will discuss in the following sections, he rejects Śaṃkara’s ontological claims regarding the nature of the ultimate reality as well as his assertions regarding the goal of human existence and the most expedient path to the realization of the goal.

Contending Ontologies

The early Gauḍīya authorities deploy a series of arguments to challenge the monistic ontology of Advaita Vedānta and the dualistic ontology of Pātañjala Yoga, whose positions I discussed briefly in the Introduction.41

Classical Advaita Vedānta, as expounded by Śaṃkara, is based on a monistic ontology that identifies the ultimate reality with Brahman, an impersonal unitary reality that in its essential nature is nirguṇa, completely devoid of attributes, and as such is described as undifferentiated (nirviśeṣa), nonactive (niṣkriya), and formless (nirākāra). In refutation of the Advaitins’ characterizations of the ultimate reality, the early Gauḍīya authorities assert that, on the contrary, the highest aspect of the Godhead is personal, replete with infinite qualities (saguṇa), differentiated (saviśeṣa), possessed of innumerable śaktis (śaktimat), and endowed with an absolute body (vigraha) that is nonmaterial (aprākṛta). Moreover, in opposition to the Advaitin ontological hierarchy in which the personal God is identified with saguṇa Brahman and is associated with the domain of māyā as a lower manifestation of the impersonal nirguṇa Brahman, the Gauḍīyas maintain that the impersonal Brahman is itself subsumed within the supreme personal Godhead as an incomplete manifestation (asamyag-āvirbhāva) of Bhagavān. In the Gauḍīya perspective Brahman is simply the effulgence that shines forth from the self-luminous absolute body of Bhagavān (tanu-bhā or aṅga-prabhā). Moreover, they assert that the joy that arises from realization of the impersonal, formless Brahman is as insignificant as a tiny puddle of water contained in a cow’s hoofprint when compared to the pure ocean of bliss (āhlāda-viśuddhābdhi) that arises from direct visionary experience (sākṣāt-kāra) of Bhagavān’s absolute body.42 In addition to countering Advaitin perspectives on the nature of the ultimate reality, the early Gauḍīya authorities also develop arguments to refute their doctrines of māyā and ignorance (avidyā) and their claims regarding the identity of the jīva with Brahman.43

The early Gauḍīya authorities also provide a critical assessment of the dualistic ontology advanced by the advocates of Pātañjala Yoga, which builds upon the ontology and epistemology of Sāṃkhya. In their hierarchical assessment of contending ontologies, the Gauḍīyas allot a higher place to the dualistic ontology of Pātañjala Yoga than to the monistic ontology of Advaita Vedānta. In the Gauḍīya perspective the Pātañjala Yoga goal of kaivalya, in which the yogin awakens to the reality of the nonchanging Self, puruṣa, as distinct from prakṛti and from other puruṣas, is a higher state of realization than the Advaitin goal of mokṣa, in which the jīvanmukta awakens to the reality of the universal Self, Ātman, as identical with the distinctionless unitary reality, Brahman. The Gauḍīyas understand the Pātañjala Yoga goal of realization of puruṣa as pointing to the realization of saviśeṣa (differentiated) Paramātman, which they assert is a higher state than the realization of nirviśeṣa (undifferentiated) Brahman. However, while the advocates of Pātañjala Yoga are viewed as avoiding the Advaitin extreme of absolute unity, they are critiqued for indulging in the opposite extreme of absolute separation. While they are applauded for maintaining the distinctions among the plurality of puruṣas—which the Gauḍīyas term jīvas—they are chided for failing to recognize that the individual jīvas are themselves parts (aṃśas) of a greater all-encompassing totality: Bhagavān, who is Puruṣottama, the supreme Puruṣa, and who subsumes within himself both saviśeṣa Paramātman and nirviśeṣa Brahman as partial aspects of his totality.

Contending Paths

The Gauḍīya critiques of Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga are articulated as a contestation among paths (mārgas) to realization in which the bhakti-mārga, the path of devotion, emerges victorious as the supreme path that surpasses both the jñāna-mārga, the path of knowledge advocated by the Advaitins, and the yoga-mārga, the path of yoga advocated by the exponents of Pātañjala Yoga. The Gauḍīyas maintain that although those who follow the jñāna-mārga may realize their identity with nirviśeṣa Brahman, the lowest aspect of Kṛṣṇa, and those who follow the yoga-mārga may experience saviśeṣa Paramātman, the intermediary aspect of Kṛṣṇa, neither the jñānin nor the yogin realizes the highest aspect of Kṛṣṇa as Bhagavān, the supreme personal Godhead, who is attained through the bhakti-mārga alone.44 Invoking the canonical authority of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the Gauḍīyas declare that jñāna and yoga, when devoid of bhakti, are barren paths that cannot yield the highest fruit of realization in which one awakens to Kṛṣṇa as svayaṃ Bhagavān.

The śāstras say: abandon karma and jñāna and yoga. Kṛṣṇa is controlled by bhakti, and by bhakti he should be worshiped.… “Only that very powerful bhakti toward me [Kṛṣṇa] is able to compel me; I am not [compelled by] yoga, sāṃkhya, dharma, Vedic study, tapas,45 or renunciation.”46

The Gauḍīyas’ hierarchical analysis provides a striking example of what I term the theology of superordination in that, in contrast to a theology of supersessionism, the Gauḍīyas do not claim to exclude or replace the contending models of realization propounded by the exponents of Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga, but rather they posit a model of realization that incorporates and domesticates the Advaitin and Pātañjala Yoga models by recasting them as lower levels of realization of their own all-encompassing Godhead.

Contending Goals

The Gauḍīya critiques of Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga thus encompass not only the nature of their respective paths but also their formulations of the goal of human existence. For the Gauḍīyas acintya-bhedābheda, inconceivable difference-in-nondifference, is not simply an abstract ontological formulation but is the highest goal of realization in which the jīva awakens to the reality of its union-in-difference with Bhagavān. As part of their theology of superordination they relegate to subordinate positions as lower levels of realization both the goal of absolute unity or identity with Brahman advanced by the Advaitins and the goal of absolute separation or isolation (kaivalya) advanced by the exponents of Pātañjala Yoga. In this context they provide a critique of the formulations of liberation, mokṣa or mukti, propounded by both schools.

The Gauḍīyas’ critical assessment of mukti includes an analysis of five types of liberation, which they recast from a theistic perspective as five modes of realization of the deity: sālokya, in which one resides in the world (loka) of the deity; sārṣṭi, in which one enjoys the powers of the deity; sāmīpya, in which one lives near the deity; sārūpya, in which one assumes a form (rūpa) like that of the deity; and sāyujya, in which one attains undifferentiated unity with the deity. Invoking the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as their scriptural authority, the Gauḍīyas reject all five types of mukti—sālokya, sārṣṭi, sāmīpya, sārūpya, and sāyujya—and assert that true bhaktas do not desire any form of liberation but rather cherish bhakti, selfless devotion to Kṛṣṇa, as the highest end of human existence.

The distinguishing characteristic of unqualified bhakti-yoga is declared to be that devotion (bhakti) to the supreme Puruṣa [Kṛṣṇa] which is without motive and ceaseless. Even if sālokya, sārṣṭi, sāmīpya, sārūpya, and ekatva (unity) are offered, devotees do not accept anything except worship (sevana) of me. This very thing called bhakti-yoga is declared to be the highest end.47

Among the various types of mukti, the Gauḍīyas disparage in particular sāyujya, or ekatva, for they consider it to be synonymous with the Advaitin goal of absolute unity in which the realized sage merges with the impersonal Brahman like a drop merging with the ocean.48 In the Gauḍīya hierarchy of models of realization, the ultimate goal is not nonduality but rather union-in-difference in which some distinction between the subject (āśraya) and the divine object of devotion (viṣaya) is maintained so that the bhakta can enjoy eternally the bliss of preman, the fully mature state of supreme love for Kṛṣṇa. Having realized its true identity as an aṃśa of the supreme Godhead, the jīva savors the exhilarating sweetness of preman in eternal relationship with Bhagavān. Consistent with the principle of superordination, the Gauḍīyas assert that the realized bhakta who has attained Kṛṣṇa-preman is the “crest-jewel of muktas,”49 for although liberation is not the goal of the bhakta, it is the natural byproduct of the perfected state of preman.

Ananta-Rūpa: The Limitless Forms of the Absolute Body

The Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, by providing a hierarchical assessment of the Godhead that relegates Brahman and Paramātman to subordinate positions as partial aspects of Bhagavān, thus serves to domesticate and subordinate the ontologies, paths, and goals of two competing philosophical schools, Advaita Vedānta and Pātañjala Yoga. The principle of superordination is also at work in a related Gauḍīya taxonomy, which provides a hierarchical assessment of the multifarious divine forms of Kṛṣṇa that accommodates and subordinates the contending notions of divinity promulgated by rival Vaiṣṇava and Śaiva bhakti movements.

The starting-point for Gauḍīya reflections on the divine forms is the notion that Kṛṣṇa, while maintaining the integrity of his vigraha, absolute body simultaneously assumes innumerable forms (sarva-rūpa-svabhāvatva) on the transcosmic, macrocosmic, and microcosmic planes of existence. Kṛṣṇa has only one vigraha, but the absolute body assumes a limitless (ananta) array of divine forms, termed rūpas, which all participate to a greater or lesser degree in the svarūpa, Kṛṣṇa’s essential form.50 These divine forms are classified and ranked in a hierarchical taxonomy that distinguishes three principal categories of rūpas: prakāśas, vilāsas, and avatāras. As we shall see, prakāśa, vilāsa, and avatāra are the key terms in the complex technical vocabulary that is used to designate distinct classes of divine manifestations.

The basic categories of this hierarchical taxonomy of divine forms are delineated by Rūpa Gosvāmin in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta. Jīva Gosvāmin provides philosophical arguments to support the taxonomy in the Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha. In the Caitanya Caritāmṛta Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja expands on Rūpa’s taxonomy and seeks to provide an encompassing analytical framework that systematically and precisely defines the distinctive characteristics of each category of divine forms and its relationship to other categories. In the course of elaborating this taxonomy, the early Gauḍīya authorities selectively appropriate and recast a variety of Vaiṣṇava traditions, including the Pāñcarātra theory of vyūhas, divine emanations, which posits four principal vyūhas of the supreme Godhead, who is referred to as Nārāyaṇa or Viṣṇu: Vāsudeva, Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha.51 The Gauḍīyas also reimagine Purāṇic theories of creation, cycles of time, and avatāra.52 In this section I will focus on Rūpa’s formulation of the taxonomy of divine forms in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta and on Kṛṣṇadāsa’s adaptation and expansion of Rūpa’s categories in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta.

The Source and Container of Avatāras

In their recasting of Purāṇic theories of avatāra the early Gauḍīya authorities emphasize that Kṛṣṇa, as svayaṃ Bhagavān, is not himself an avatāra, but rather he is the avatārin who is the source and container of all avatāras, descending to the material realm periodically and assuming a variety of forms in different cosmic cycles.53 They provide scriptural evidence to ground this claim by invoking the Bhāgavata Purāṇa’s account of twenty-two avatāras, which culminates in the mahā-vākya that “Kṛṣṇa is Bhagavān svayam”:

O brahmins, the avatāras of Hari, who is the ocean of being, are countless, like thousands of streams flowing from an inexhaustible lake.… All these are portions (aṃśas) or fractions of portions (kalās) of the supreme Person, but Kṛṣṇa is Bhagavān himself (Bhagavān svayam).54

Building on the language and imagery of the Bhāgavata, the Gauḍīyas maintain that Kṛṣṇa, the inexhaustible plenitude of being, sends forth an endless stream of avatāras, which are partial manifestations—whether aṃśas, portions, or kalās, fractions of portions—of his absolute body consisting of sat-cit-ānanda.

Kṛṣṇa is the highest Īśvara, svayaṃ bhagavān, the container of avatāras, and the chief cause of everything. The infinite Vaikuṇṭha and the infinite avatāras, the infinite Brahmā-worlds—he is the receptacle of all of these. He is Vrajendranandana [the son of Nanda the lord of Vraja], whose body is sat, cit, and ānanda; he possesses all majesty, all śaktis, and is full of all rasa.55

The Paradigmatic Vigraha and Its Manifold Bodily Forms

In the Gauḍīya discourse of divine embodiment, the paradigmatic body is the svayaṃ-rūpa, the essential form of the vigraha, which is distinguished by a number of bodily features and marks. Bhagavān’s svayaṃ-rūpa is that of Gopāla Kṛṣṇa, who has the form of a cowherd boy (gopa-mūrti), with two arms (dvi-bhuja), eyes like lotuses (ambujākṣa), and a dark blue-black (śyāma) complexion the color of a rain-cloud. Gopāla Kṛṣṇa has distinctive body marks such as the Śrīvatsa mark on his chest and sixteen marks on his feet, wears yellow garments and a crest of peacock feathers on his head, is adorned with a garland of forest flowers and jeweled ornaments, and carries a flute (veṇu, vaṃśī, or muralī) as his most characteristic emblem. He is celebrated for the extraordinary beauty (saundarya or lāvaṇya) and sweetness (mādhurya) of his eternally youthful (kiśora) absolute body.

Kṛṣṇa is represented as the polymorphous Godhead who, while maintaining the integrity of his absolute body, multiplies himself and assumes an innumerable array of bodies in order to fulfill particular functions on the transcosmic, macrocosmic, and microcosmic planes. The Gauḍīyas maintain that these bodies, as aṃśas or kalās of Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa, are not part of the material realm of prakṛti where the māyā-śakti reigns, but rather, like the svayaṃ-rūpa, they are nonmaterial (aprākṛta) and consist of sat-cit-ānanda. In the Gauḍīya taxonomy of divine forms, as we shall see, these bodies are classified in a complex multi-tiered schema with attention to the bodily features of each category and are ranked according to the extent to which these features conform to or diverge from the paradigmatic svayaṃ-rūpa. In this taxonomy Kṛṣṇa is represented as “appearing in” (root bhū + prādur, root bhū + āvir, root as + āvir, or root vyañj) or “assuming” (root dhṛ, root bhṛ, or root grah) or “entering” (root viś + ā) different types of bodies, which are variously termed mūrti, vapus, tanu, or deha. The range of corporeal forms includes not only the bodies of deities but also human bodies, animal bodies, and a variety of hybrid forms, such as half-human/half-animal bodies and semidivine forms. These bodily forms of Kṛṣṇa are distinguished according to their age (vayas), ranging from perpetual five-year-olds to the grandfather of the gods, and according to their color (varṇa), whether black, blue-black, green, golden, tawny, rose, red, or white. They are further distinguished by their number of heads (mukhas or śīrṣas), ranging from a single head to four or five heads to a thousand heads, and by their number of arms (bhujas or bāhus), which can range from two to four to a thousand. The other characteristics that distinguish Kṛṣṇa’s various bodily forms include specific body marks (aṅkas), modes of dress (veśa), ornaments (bhūṣaṇas) and embellishments (upāṅgas), weapons (astras), and other emblems (lakṣaṇas).

Divine Bodies and Space

In addition to their bodily features, a second factor that distinguishes Kṛṣṇa’s divine forms is their relationship to space as delineated in Gauḍīya cosmography, which maps the location and configuration of their respective abodes and spheres of influence. In this section I will provide a brief overview of Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja’s representations of this cosmography in the Caitanya Caritāmṛta, in which he expands on Rūpa Gosvāmin’s reflections in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta. Later, in Chapter 5, I will examine the framework for Gauḍīya cosmography that is delineated by Rūpa in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta and elaborated on by Jīva Gosvāmin in the Kṛṣṇa Sandarbha, in which the Gosvāmins are concerned in particular with developing an ontology of the dhāmans (abodes) of Kṛṣṇa.

Gauḍīya cosmography, as represented by Kṛṣṇadāsa, appropriates and adapts certain aspects of Purāṇic cosmographies, particularly as elaborated in the Uttara Khaṇḍa of the Padma Purāṇa, and is divided into three principal domains. Two of these domains—Kṛṣṇaloka and Paravyoman—are transcendent (parama), eternal (nitya), and nonmaterial (aprākṛta) manifestations of the svarūpa-śakti. Although spatial language and imagery are used at times to represent Kṛṣṇaloka as a transcendent space, both Kṛṣṇaloka and Paravyoman are considered beyond the material space-time continuum of prakṛti and beyond Brahman. The third domain is the material realm of prakṛti where jīvas dwell, which is delimited by the finite boundaries of time and space and governed by the māyā-śakti.56

The center of Gauḍīya cosmography is Kṛṣṇaloka, the transcendent dhāman where Kṛṣṇa engages eternally in his unmanifest (aprakaṭa) līlā as svayaṃ Bhagavān. As mentioned earlier, Kṛṣṇaloka is subdivided into three dhāmans: the innermost dhāman of Goloka-Vṛndāvana, the transcendent Vraja, and the outer dhāmans of Mathurā and Dvārakā. According to this hierarchical cosmography, Kṛṣṇa manifests himself “most fully” (pūrṇatama) in Goloka-Vṛndāvana, where he engages in līlā that is characterized by mādhurya, divine sweetness; he manifests himself “more fully” (pūrṇatara) in Mathurā, where he engages in līlā that is characterized by a mixture of mādhurya and aiśvarya, divine majesty; and he manifests himself “fully” (pūrṇa) in Dvārakā, where he engages in līlā in which aiśvarya predominates.57 Whereas in Goloka-Vṛndāvana he resides eternally in his svayaṃ-rūpa, his most full and complete form as Gopāla Kṛṣṇa, in Mathurā and Dvārakā he appears in four divine manifestations known as the ādi catur-vyūhas, which, as I will discuss later, are classified in the taxonomy of divine forms as prābhava-vilāsas. Kṛṣṇadāsa emphasizes that while Goloka-Vṛndāvana, Mathurā, and Dvārakā exist beyond the material space-time continuum as the transcendent (parama), infinite (ananta), and eternal (nitya) abodes of Kṛṣṇa’s unmanifest līlā, they appear within the circumscribed boundaries of space and time when Kṛṣṇa descends to the material realm and engages in his manifest līlā.58 More specifically, the earthly region of Vraja in North India is understood to be the immanent counterpart of Kṛṣṇa’s transcendent Vraja-dhāman, Goloka-Vṛndāvana, and the site where he manifests his svayaṃ-rūpa, his two-armed form as a cowherd boy, in the material realm and displays his manifest līlā.

In Gauḍīya cosmography, as articulated by Kṛṣṇadāsa, Kṛṣṇaloka is surrounded by Paravyoman (or Paramavyoman), the transcendent domain beyond vyoman, the subtle element of space that is the finest level of objective material existence. Paravyoman is presided over by Kṛṣṇa in his four-armed form as Nārāyaṇa and is the domain of Kṛṣṇa’s innumerable divine rūpas that are classified in the taxonomy as vaibhava-vilāsas and avatāras, each of which has his own abode, or Vaikuṇṭha. The transcendent domains of Kṛṣṇaloka and Paravyoman are at times represented as a lotus-maṇḍala in which Kṛṣṇaloka is the pericarp (karṇikāra), the seed-vessel in the center of a lotus, and the Vaikuṇṭhas of Paravyoman are the countless petals that encircle the pericarp.59 Paravyoman is in turn encircled by a luminous ring of light, which is the undifferentiated effulgence of Brahman that shines forth from Kṛṣṇa’s absolute body and which is called siddha-loka because it is the abode of those who have attained sāyujya and merged with Brahman.60 Encircling the effulgence of Brahman is the endless ocean of causality, kāraṇābdhi or kāraṇārṇava, which is also known as Virajā and which is made of consciousness (cit) and acts as a moat separating Paravyoman from the material realm of prakṛti that is governed by the māyā-śakti. The material realm comprises limitless Brahmā-universes (brahmāṇḍas, literally, “Brahmā-eggs”), which are depicted as floating on the ocean of causality in the form of cosmic eggs, each of which contains its own Brahmā the creator.61 These Brahmā-universes each contain a hierarchy of fourteen material worlds (lokas or bhuvanas), with the earth, bhūr-loka, in the middle and six higher worlds above the earth and seven lower worlds beneath the earth.62 As we shall see, the avatāras of Kṛṣṇa are represented as descending periodically from their eternal abodes in Paravyoman to the material realm of the Brahmā-universes in order to fulfill specific cosmic functions.

Divine Bodies and Time

In addition to their bodily features and relationship to space, a third factor that distinguishes Kṛṣṇa’s divine forms is their relationship to time. The avatāras’ descent into the material realm of prakṛti is a descent into the material space-time continuum, and the various classes of avatāras are associated with different cycles of time. The early Gauḍīya authorities appropriate in this context Purāṇic cosmogonic conceptions in which creation occurs in endlessly repeating cycles of creation and dissolution. Purāṇic cosmogonies distinguish four basic units of time that compose these cycles: yugas, mahā-yugas, manvantaras, and kalpas. A mahā-yuga is a cycle of four yugas, or ages—Satya or Kṛta Yuga (1,728,000 years), Tretā Yuga (1,296,000 years), Dvāpara Yuga (864,000 years), and Kali Yuga (432,000 years)—comprising a total of 4,320,000 years. One thousand mahā-yugas (4,320,000,000 years) constitute a kalpa, a single day of the creator Brahmā. Every kalpa, or day of Brahmā, is also subdivided into fourteen manvantaras, or intervals of Manu, each comprising seventy-one and a fraction mahā-yugas. In Purāṇic cosmogonies these units of time are incorporated in a more encompassing framework that distinguishes between sargas, primary creations, and pratisargas, secondary creations. A sarga occurs at the beginning of each new lifetime of Brahmā, whereas a pratisarga occurs at the beginning of each new day in the life of Brahmā, or kalpa. At the end of each kalpa Brahmā sleeps for a night and a minor dissolution (pralaya) occurs, after which Brahmā awakens and initiates a new pratisarga. At the end of Brahmā’s lifetime, which consists of one hundred years of Brahmā days and nights, a major dissolution (mahā-pralaya) occurs, after which a new sarga begins As we shall see, the Gauḍīya taxonomy of divine forms correlates the five principal classes of avatāras with these Purāṇic cycles of time: the puruṣa-avatāras are ascribed a critical role in the sargas and pratisargas; the guṇa-avatāras, in the pratisargas; the līlā-avatāras, in the kalpas; the manvantara-avatāras, in the manvantaras; and the yuga-avatāras, in the yugas.

Taxonomy of Kṛṣṇa’s Divine Forms

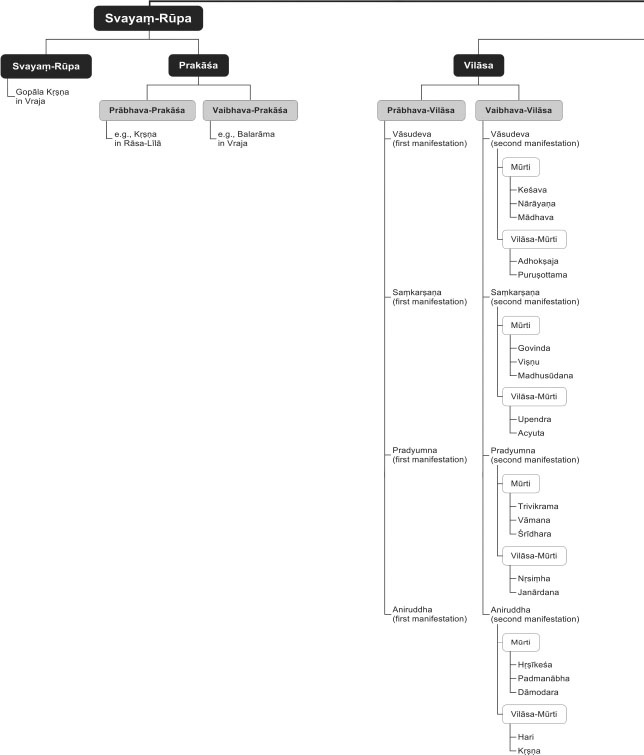

I shall turn now to an analysis of the Gauḍīya classificatory system, focusing in particular on the ornate hierarchical taxonomy delineated by Kṛṣṇadāsa in Caitanya Caritāmṛta 2.20 and 1.5, which expands on and adapts the categories presented by Rūpa in the Laghubhāgavatāmṛta. This system, as delineated by both Rūpa and Kṛṣṇadāsa, distinguishes three encompassing categories of Kṛṣṇa’s rūpas—svayaṃ-rūpa, tadekātma-rūpa, and āveśa-rūpa—each of which is further divided and subdivided into a series of subsidiary categories.63 An overview of this classificatory system is provided in Figure 2.

1 Svayaṃ-Rūpa. Rūpa defines svayaṃ-rūpa as “that rūpa which is not dependent on anything else (ananyāpekṣin).”64 He identifies the svayaṃ-rūpa with Kṛṣṇa’s gopa form as Govinda, the keeper of cows, whose absolute body (vigraha) is described in Brahma Saṃhitā 5.1 as consisting of sat-cit-ānanda: “Kṛṣṇa is the supreme Īśvara, Govinda, whose body (vigraha) consists of sat, cit, and ānanda, who is beginningless yet the beginning of all, the cause of all causes.”65 Kṛṣṇadāsa, building on Rūpa’s identification of the svayaṃ-rūpa with the vigraha, emphasizes the singular nature of Kṛṣṇa’s perfect form as a gopa, a two-armed flute-playing cowherd boy, who revels eternally in mādhurya, the sweetness of his unmanifest līlā in Goloka-Vṛndāvana, the transcendent Vraja-dhāman. He maintains, moreover, that the svayaṃ-rūpa appears in two forms: as the svayaṃ-rūpa itself and as prakāśa.66

1.1 Svayaṃ-Rūpa. The svayaṃ-rūpa itself is one (eka) and undivided: Kṛṣṇa in the form of a gopa (gopa-mūrti) in Vraja.67

1.2 Prakāśa. Prakāśa is a manifestation of the svayaṃ-rūpa that is nondifferent from Kṛṣṇa’s essential form. Kṛṣṇadāsa further subdivides prakāśa into two categories: prābhava-prakāśa and vaibhava-prakāśa.

1.2.1 Prābhava-Prakāśa. Kṛṣṇadāsa’s understanding of prābhava-prakāśa draws on Rūpa’s definition of prakāśa, although Rūpa himself does not classify prakāśa as a subdivision of svayaṃ-rūpa: “The manifestation (prakaṭatā) of one body in many places at the same time, identical with the svarūpa in every respect, is called prakāśa.”68 Prābhava-prakāśa, in Kṛṣṇadāsa’s formulation, is when the one vigraha appears in many forms (rūpas) in many places simultaneously and there is no difference between the many forms and the svayaṃ-rūpa. The paradigmatic example of prābhava-prakāśa is Kṛṣṇa’s performance of the rāsa-līlā, the circle dance with the gopīs, the cowmaidens of Vraja, in which he multiplies himself and assumes a separate form for each gopī, and each form is equally real and nondifferent from the svayaṃ-rūpa.69

1.2.2 Vaibhava-Prakāśa. Vaibhava-prakāśa is when the one vigraha, without changing its essential bodily shape (mūrti), manifests forms that are assigned different names due to differences in sentiment (bhāva), color (varṇa), or other features. When Kṛṣṇa, without abandoning his svayaṃ-rūpa, manifests temporarily a four-armed (catur-bhuja) form characterized by aiśvarya in his kṣatriya-bhāva (royal mode) as Vāsudeva, the Yādava prince who is the son of Vasudeva and Devakī, this four-armed form is an example of vaibhava-prakāśa. Balarāma, who appears as Kṛṣṇa’s cowherd brother in Vraja, is also considered a vaibhava-prakāśa because his form is the same as Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa in every respect except for the color of his complexion, which is white rather than blue-black.70

2 Tadekātma-Rūpa. Tadekātma-rūpa is the second of the three encompassing categories into which Rūpa divides Kṛṣṇa’s forms (see Figure 2). Rūpa uses the term tadekātma-rūpa to designate divine manifestations of the vigraha that are different in shape (ākṛti) and other features from the svayaṃ-rūpa.71 Kṛṣṇadāsa expands on this definition: “That body [vapu] takes different forms, and has different reflections; and the name of it when different in sentiment [bhāva], emotion [āveśa], and shape [ākṛti] is tadekātma-rūpa.”72 Kṛṣṇadāsa follows Rūpa in subdividing tadekātma-rūpa into two categories: vilāsa, a category of divine manifestations; and svāṃśa, a category of divine forms that comprises five different classes of avatāras.73 As we shall see, this taxonomy reverses the hierarchy in the prevailing Vaiṣṇava paradigm—in which Kṛṣṇa is represented as simply one among many avatāras sent forth by the avatārin Viṣṇu—by asserting that Kṛṣṇa himself is the avatārin who is the source of all avatāras and the source of all vilāsas, including Viṣṇu in all of his manifestations.

Figure 2 Taxonomy of Kṛṣṇa’s Divine Forms.

2.1 Vilāsa. A vilāsa is a divine manifestation of the vigraha that is distinguished from the svayaṃ-rūpa primarily by a difference in bodily shape (ākāra). Rūpa provides the following definition of vilāsa: “When [Kṛṣṇa’s] svarūpa, by means of his śakti, appears for the sake of līlā in another shape (ākāra) that is for the most part the same as the [absolute] body, it is called vilāsa.”74 While Kṛṣṇadāsa initially follows Rūpa in highlighting difference in shape (ākāra) as the distinguishing mark of a vilāsa,75 he goes beyond Rūpa in highlighting a number of additional bodily features that differentiate a vilāsa from the svayaṃ-rūpa, including name (nāma), color (varṇa), number of arms (bhujas), mode of dress (veśa), and weapons (astras). He also goes beyond Rūpa in constructing an elaborate system of vilāsas that is subdivided into two categories: prābhava-vilāsas and vaibhava-vilāsas. This system enables Kṛṣṇadāsa to organize the various names and forms of Viṣṇu celebrated by historically discrete Vaiṣṇava traditions—including the Pāñcarātra theory of vyūhas—into a single overarching framework that relegates Viṣṇu, in all of his forms, to a subsidiary position as a manifestation of Kṛṣṇa, svayaṃ Bhagavān.

2.1.1 Prābhava-Vilāsa. In developing his system of vilāsas, Kṛṣṇadāsa invests the older Pāñcarātra conception of vyūhas with a distinctively Gauḍīya inflection by identifying the prābhava-vilāsas with the ādi catur-vyūhas, the four primordial vyūhas, divine manifestations: Vāsudeva, Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha. Whereas in Goloka-Vṛndāvana, the innermost realm of Kṛṣṇaloka, Kṛṣṇa remains eternally in his gopa-bhāva alongside his cowherd brother Balarāma, his vaibhava-prakāśa, and engages in līlā characterized by mādhurya, in Dvārakā and Mathurā he manifests four different shapes (ākāra) as the ādi catur-vyūhas and engages in līlā characterized by aiśvarya: Vāsudeva, the four-armed manifestation of Kṛṣṇa in his kṣatriya-bhāva; Saṃkarṣaṇa, a manifestation of Balarāma in his kṣatriya-bhāva; Pradyumna, the son of Kṛṣṇa by his wife Rukmiṇī; and Aniruddha, the son of Pradyumna. The ādi catur-vyūhas, as partial manifestations of Kṛṣṇa’s svayaṃ-rūpa, are full of sat, cit, and ānanda.76

2.1.2 Vaibhava-Vilāsa. In Kṛṣṇadāsa’s system of vilāsas the vaibhava-vilāsas comprise twenty-four manifestations termed mūrtis, which are manifested from the ādi catur-vyūhas and reside in Paravyoman, the transcendent domain that surrounds Kṛṣṇaloka. The most important of these twenty-four mūrtis are a second set of catur-vyūhas in Paravyoman—Vāsudeva, Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha—who replicate the ādi catur-vyūhas in Kṛṣṇaloka. Here they surround Nārāyaṇa, Kṛṣṇa’s four-armed form who is the presiding deity of Paravyoman. Each of the four vyūhas has three mūrtis, and these twelve mūrtis are ascribed the role of presiding deities of the twelve months (see Figure 2).77 Each of the four vyūhas also manifests two additional forms, and these eight manifestations are termed vilāsa-mūrtis (see Figure 2).78 The twenty-four mūrtis together are associated with the cardinal directions, with three mūrtis presiding over each of the eight directions. Thus the vaibhava-vilāsas, while residing in Paravyoman beyond the material space-time continuum, are ascribed the special function of presiding over space and time. One of the striking aspects of Kṛṣṇadāsa’s account is his emphasis on the bodily forms of the twenty-four mūrtis, which he claims are distinguished from the svayaṃ-rūpa and from each other by their shape (ākāra), dress (veśa), and weapons (astras). All twenty-four mūrtis are represented as having four arms (catur-bhuja) and as wielding the four weapons that are emblematic of Viṣṇu—discus (cakra), conch (śaṅkha), club (gadā), and lotus (padma)—but are here recast as emblems of Kṛṣṇa in his aiśvarya mode. The most significant feature that differentiates the twenty-four mūrtis, according to Kṛṣṇadāsa, is the unique configuration in which the four weapons are held in the four hands of each mūrti. A second noteworthy aspect of Kṛṣṇadāsa’s account is his claim that a number of the twenty-four vaibhava-vilāsas, while remaining established in their eternal abodes in Paravyoman, become embodied in the material realm of the Brahmā-universes as mūrtis, ritual images, enshrined in temples in particular locales in India. For example, among the twelve mūrtis presiding over the months, Keśava descends to the material realm and becomes embodied in a temple mūrti in the earthly city of Mathurā and Viṣṇu descends and becomes embodied in Viṣṇukāñcī (Kāñcīpuram). Among the eight vilāsa-mūrtis, Puruṣottama descends to the material realm and becomes embodied as Jagannātha in Nīlācala (Purī) and Hari descends and becomes embodied in Māyāpura. In Kṛṣṇadāsa’s conception of vaibhava-vilāsas, a direct connection is thus established between the mūrti as a special category of divine manifestations in the transcendent domain of Paravyoman and the mūrti as an arcā-avatāra, image-avatāra, embodied in a temple on earth.79

2.2 Svāṃśa. Svāṃśa is the second category into which Rūpa subdivides the encompassing category of tadekātma-rūpa. He defines svāṃśa as “that [form] which is similar [to the vilāsa] but manifests (root vyañj) less śakti.”80 He subsequently provides extended descriptions of five classes of avatāras that are categorized as svāṃśa forms because they are Bhagavān’s “own āṃśas” that are partial manifestations of his vigraha, absolute body: puruṣa-avatāras, guṇa-avatāras, līlā-avatāras, manvantara-avatāras, and yuga-avatāras (see Figure 2). Rūpa defines avatāras as divine forms that “appear (root as + āvir) in an unprecedented way, either directly or through an agent, in order to accomplish some work in the material realm (viśva-kārya).”81 He is also concerned with delineating the particular worlds (lokas or bhuvanas) in which the avatāras take up residence during their sojourns in the material realm of the Brahmā-universes.82 Kṛṣṇadāsa follows Rūpa in delineating five classes of svāṃśa avatāras83 and, like Rūpa, defines an avatāra as a divine form that descends into the material realm in order to fulfill specific functions in creation: “That mūrti which takes shape in the phenomenal world for the purpose of creation, that Īśvara-mūrti is called ‘avatāra.’ All of these dwell in Paravyoma, which is apart from māyā; but having descended into the universe, they have the name avatāra.”84 In the formulations of both Rūpa and Kṛṣṇadāsa we can distinguish between two principal networks of svāṃśa avatāras: (1) the puruṣa-avatāras and guṇa-avatāras, which are ascribed specific cosmogonic roles in promoting the līlā of creation in the sargas and pratisargas, the primary and secondary creations; and (2) the līlā-avatāras, manvantara-avatāras, and yuga-avatāras, which are ascribed specific functions in upholding the līlā of dharma in different cosmic cycles, in particular the kalpas, manvantaras, and yugas, respectively.85 As we shall see, in delineating the cosmogonic functions of the puruṣa-avatāras and guṇa-avatāras, Rūpa and Kṛṣṇadāsa appropriate and reimagine the complex array of creation narratives in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa in the form of a single cosmogonic account. In delineating the dharmic functions of the līlā-avatāras, manvantara-avatāras, and yuga-avatāras, they attempt to generate a coherent system from the various networks of avatāras discussed in different sections of the Bhāgavata by clustering them in separate categories, naming them, and subsuming them in an encompassing taxonomy that seeks to illumine the distinctions and interconnections among the discrete taxa.

2.2.1 Puruṣa-Avatāra. Within the threefold hierarchy of the Godhead, as discussed earlier, Paramātman, the intermediary aspect of Bhagavān, is represented as the indwelling Self of the macrocosmos who creates, maintains, and destroys the material realm of prakṛti and as the indwelling Self of the microcosmos who is the inner controller of jīvas, embodied beings. In this context Paramātman serves as the source and ground of the three puruṣa-avatāras who are responsible for bringing forth and maintaining the material realm and all jīvas in the sargas, primary creations, and pratisargas, secondary creations. Rūpa identifies the three puruṣa-avatāras more specifically with three manifestations of the Paramātman in the form of Viṣṇu and invokes as a prooftext an unidentified passage from the Sātvata Tantra: “Viṣṇu has three forms (rūpas) that they designate by the name puruṣa: the first is the creator of mahat [the first evolute of prakṛti]; the second abides in the cosmic eggs (aṇḍas); the third resides in all embodied beings (bhūtas).”86 In his discussion of the three puruṣa-avatāras, Rūpa identifies these three forms of Viṣṇu as manifestations of three of the catur-vyūhas, discussed earlier, who reside eternally in Paravyoman—Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha—and who are classified in Kṛṣṇadāsa’s taxonomy as vaibhava-vilāsas. Rūpa’s discussion of the three puruṣa-avatāras relies primarily on illustrative passages from the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and Brahma Saṃhitā. Kṛṣṇadāsa’s expanded exposition recasts the Bhāgavata Purāṇa’s profusion of complex and disparate creation accounts in the form a single cosmogonic narrative in which he associates each of the three puruṣa-avatāras with a key moment in the narrative.87 Kṛṣṇadāsa follows Rūpa in identifying the three puruṣa-avatāras with three forms of Viṣṇu whose names—Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu, Garbhodakaśāyin Viṣṇu, and Kṣīrodakaśāyin Viṣṇu—derive from their distinctive bodily postures as reclining figures who rest (śāyin) on three different oceans (abdhi or udaka) associated with different phases in the cosmogonic process. Moreover, as we shall see, Kṛṣṇadāsa elaborates on the particular functions of the three puruṣa-avatāras as the inner controllers, antar-yāmins, who are associated with different aspects of embodiment: the first puruṣa-avatāra is the Self of the collective totality of the Brahmā-universes who encompasses the innumerable cosmos bodies within his divine body; the second puruṣa-avatāra is the indwelling Self within each separate cosmos body, or Brahmā-universe; and the third puruṣa-avatāra is the indwelling Self within the body of each individual jīva and within the fourteen worlds contained in each cosmos body.88

2.2.1.1 Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu (Saṃkarṣaṇa). The first puruṣa-avatāra, the ādi-puruṣa, is Mahāviṣṇu, who is represented by Rūpa as a manifestation of Saṃkarṣaṇa and is called Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu because he reclines in the form of Nārāyaṇa on the ocean of causality (kāraṇābdhi or kāraṇārṇava) that separates Paravyoman from the material realm of prakṛti governed by the māyā-śakti.89 According to Kṛṣṇadāsa’s expanded account, Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu, the ādi-puruṣa, provides the impetus for the sarga to begin by activating māyā with his glance and sowing his seed in the form of jīvas in the womb of prakṛti. The equilibrium of the guṇas, the three constituents of prakṛti, is thereby broken, and the sarga begins with the emergence of the twenty-three tattvas, the evolutes of primordial matter, along with their presiding deities (devatās): cosmic intelligence (mahat), ego (ahaṃkāra), mind (manas), five sense capacities (buddhīndriyas), five action capacities (karmendriyas), five subtle elements (tanmātras), and five gross elements (mahā-bhūtas). The tattvas of prakṛti then combine to form innumerable Brahmā-universes (brahmāṇḍas) in the form of cosmic eggs. Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu is celebrated as the inner controller (antar-yāmin) of the entire material realm constituted by prakṛti who encompasses within his body the innumerable Brahmā-eggs. Building on the imagery of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa,90 Kṛṣṇadāsa maintains that each time he exhales, innumerable Brahmā-eggs issue forth from his body (śarīra) through the pores of his skin, and each time he inhales they are withdrawn again into his body.91 Kṛṣṇadāsa emphasizes, moreover, the special function of Mahāviṣṇu, or Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu, as the ādi avatāra of Bhagavān who is the seed of all avatāras (sarva-avatāra-bīja). Although Kṛṣṇa alone is svayaṃ avatārin, the ultimate source of all avatāras, it is Mahāviṣṇu in his threefold manifestation as the three puruṣa-avatāras, according to Kṛṣṇadāsa, who is extolled as the immediate source of the various avatāras. In his manifestation as Kāraṇābdhiśāyin Viṣṇu, the first puruṣa-avatāra, who is an aṃśa of Kṛṣṇa, he is the source of the līlā-avatāras. In his partial manifestation as Garbhodakaśāyin Viṣṇu, the second puruṣa-avatāra, who is an aṃśa of an aṃśa, he is the source of the guṇa-avatāras, and in his partial manifestation as Kṣīrodakaśāyin Viṣṇu, the third puruṣa-avatāra, who is an aṃśa of an aṃśa of an aṃśa, he is the source of the manvantara-avatāras and the yuga-avatāras.92